Abstract

AIM: To compare the risk of developing advanced colorectal neoplasm (ACRN) according to age in Koreans.

METHODS: A total of 70428 Koreans from an occupational cohort who underwent a colonoscopy between 2003 and 2012 at Kangbuk Samsung Hospital were retrospectively selected. We evaluated and compared odds ratios (OR) for ACRN between the young-adults (YA < 50 years) and in the older-adults (OA ≥ 50 years). ACRN was defined as an adenoma ≥ 10 mm in diameter, adenoma with any component of villous histology, high-grade dysplasia, or invasive cancer.

RESULTS: In the YA group, age (OR = 1.08, 95%CI: 1.06-1.09), male sex (OR = 1.26, 95%CI: 1.02-1.55), current smoking (OR = 1.37, 95%CI: 1.15-1.63), family history of colorectal cancer (OR = 1.46, 95%CI: 1.01-2.10), diabetes mellitus related factors (OR = 1.27, 95%CI: 1.06-1.54), obesity (OR = 1.23, 95%CI: 1.03-1.47), CEA (OR = 1.04, 95%CI: 1.01-1.09) and low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (OR = 1.01, 95%CI: 1.01-1.02) were related with an increased risk of ACRN. However, age (OR = 1.08, 95%CI: 1.06-1.09), male sex (OR = 2.12, 95%CI: 1.68-2.68), current smoking (OR = 1.38, 95%CI: 1.12-1.71), obesity (OR = 1.34, 95%CI: 1.09-1.65) and CEA (OR = 1.05, 95%CI: 1.01-1.09) also increased the risk of ACRN in the OA group.

CONCLUSION: The risks of ACRN differed based on age group. Different colonoscopic screening strategies are appropriate for particular subjects with risk factors for ACRN, even in subjects younger than 50 years.

Keywords: Young-adult, Advanced colorectal neoplasm, Risk factors, Age, Metabolic abnormality

Core tip: The development of colorectal cancer can be prevented through screening colonoscopy with detection and removal of advanced colorectal adenomas. Age is an important risk factor for development of advanced colorectal neoplasm (ACRN). Risk factors for the development of ACRN differ between young adults (YA, < 50 years) and older adults (OA, ≥ 50 years). Metabolic abnormalities including diabetes mellitus related factors and serum level of low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol were more related with increased risk of ACRN in the YA group. Different colonoscopic screening strategies would be appropriate to the particular subjects with risk factors for ACRN, even those younger than 50 years.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) has primarily been considered a Western disease, however, the incidence and mortality of CRC has been increasing in Asia, especially in South Korea[1]. The estimated age-standardized rate of CRC was high in world-wide of 45.0 per 100000 in South Korea[2,3]. CRC has become an important clinical burden in South Korea. It has been well documented that most CRC arises from colorectal adenomas (CRA)[4]. Especially, advanced CRA is a definite precancerous lesion and the development of CRC can be prevented with a screening colonoscopy that detects and removes advanced CRA[5].

Unlike other cancers, no single risk factor accounts for most cases of CRC[6]. It has been reported that old age, male sex, family history, diabetes mellitus (DM), smoking, alcohol, obesity and inflammatory bowel disease were related with the development of advanced colorectal neoplasm (ACRN) and modifiable factors including dietary factor and exercise affect ACRN as well[6].

Recently, screening using colonoscopy has decreased the incidence of CRC[7,8]. However, the prevalence of ACRN is still around 3.5% in subject younger than 50 years[9] and rectal cancer is also increased in this group[10]. In many countries including South Korea, fecal occult blood testing or colonoscopy is used for CRC screening starting at the age of 50[11,12]. Few studies investigate the risk factors for ACRN in large cohorts of subjects younger than 50 years. In these backgrounds, the aim of the present study was to compare the differences for risk factors of ACRN between the subjects younger or older than 50 years in a large population of Korean subjects who underwent screening a colonoscopy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

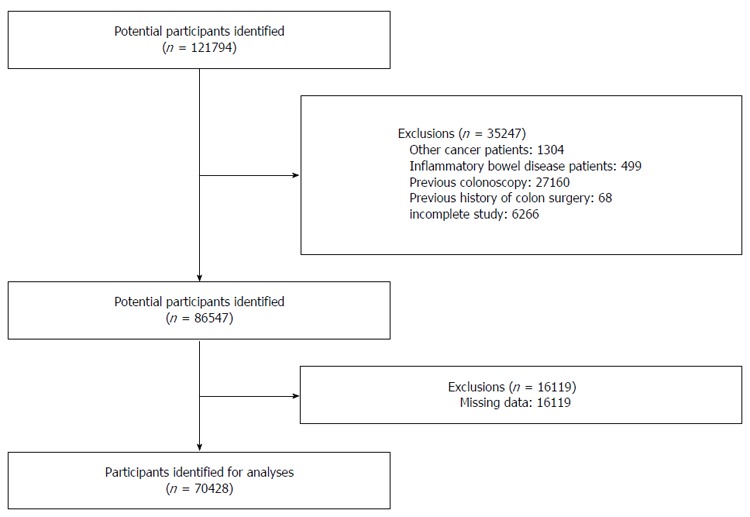

The study population consisted of subjects who underwent a comprehensive health examination between 2003 and 2012 at Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, College of Medicine, Sungkyunkwan University. We excluded (1) patients with a history of other cancers; (2) patients with a history of inflammatory bowel disease; (3) patients who had taken a previous colonoscopy; (4) patients who had undergone colon surgery; (5) patients who had an incomplete colonoscopy; and (6) patients with missing data. The flow chart of subject inclusion and exclusion of subjects in analysis is described in Figure 1. The study population was classified into two groups according to age. Patients who were younger than 50 were defined as the young-adult (YA) group and while those who were older than 50 were assigned to the older-adult (OA) group. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of subject enrollment.

Measurements

Data on medical history, medication use, and health-related behaviors were collected through a self-administered questionnaire under the supervision of a well-trained interviewer. Alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking were identified. A heavy drinker was defined as a subject who drinks more than 4 times per week. Family history of CRC was defined as CRC in one or more first-degree relatives at any age. The weekly frequency of moderate to vigorous physical activity was also assessed.

Physical characteristics and serum biochemical parameters were measured by a trained nurse. Body weight was measured with subjects wearing light clothing and no shoes. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. The Asia-Pacific criteria for obesity based on BMI guidelines were used to diagnose obesity[13]. Subjects with a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 were defined as obese. Trained nurses measured blood pressure using standard mercury sphygmomanometers with subjects seated after at least 10 min of rest.

Blood samples were taken from the antecubital vein after at least 10 h of fasting. Serum triglyceride and total cholesterol levels were determined using an enzymatic colorimetric assay; low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C) and high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C) levels were determined using a homogeneous enzymatic colorimetric assay. Serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels were measured by immunoassay. Serum insulin level was measured using an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay on the Modular Analytics E170 apparatus (Roche Diagnostics). Serum fasting glucose level was measured using the hexokinase method on the Cobas Integra 800 apparatus (Roche Diagnostics). The Laboratory Medicine Department at Kangbuk Samsung Hospital in Seoul, South Korea has been accredited by the Korean Society of Laboratory Medicine and the Korean Association of Quality Assurance for Clinical Laboratories.

In the present study, the authors evaluated the effect of metabolic abnormalities (MetA) on the development of ACRN. MetA was defined according to the modified National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel (NCEP-ATP) III criteria[14] as follows: (1) triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL or specific treatment for this lipid abnormality; (2) high-density lipoprotein cholesterol < 40 mg/dL for men and < 50 mg/dL for women; (3) elevated blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg or use of antihypertensive medications as hypertension (HTN)-related factors; and (4) fasting plasma glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL, hemoglobin A1c ≥ 6.5%, or use of diabetes medications as DM-related factors.

Diagnosis of colorectal neoplasm

Colonoscopies were performed by experienced colonoscopists unaware of the present study. Bowel preparations were carried out using 4 L of polyethylene glycol solution. Most subjects were consciously sedated with midazolam and pethidine. Histological assessment of all polyps was performed by experienced pathologists unaware of the subjects’ clinical data. ACRN was defined as an adenoma ≥ 10 mm in diameter, adenoma with any component of villous histology, high-grade dysplasia, or invasive cancer[15].

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables including age, BMI, blood pressure and laboratory values were expressed as mean ± SD and compared using the Student’s t-test. Categorical variables including sex, alcohol consumption, smoking status, CRC family history, underlying metabolic condition, regular exercise and development of CRC were expressed as percentages and analyzed using the χ2 test. We used multiple logistic regression analysis to determine the odds ratios (OR) for developing ACRN. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All data analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows (Version 18.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States). The present study was reviewed by our expert biostatistician, Lee MY.

RESULTS

A total of 121794 subjects underwent a screening colonoscopy and a comprehensive health examination at Kangbuk Samsung Hospital between 2003 and 2012. We excluded 1304 subjects with other cancers, 499 patients with inflammatory bowel disease, 27160 subjects with a previous colonoscopy, 68 subjects with a history of colon surgery, 6266 subjects with an incomplete colonoscopy and 16119 subjects with missing data. Finally, 70428 subjects were included in this analysis (Figure 1).

There were 59782 subjects younger than 50 and 10646 subjects older than 50. Baseline characteristics of YA and OA subjects are described in Table 1. The mean age of the YA group was 38.9 ± 5.3 years and that of the OA group was 56.5 ± 5.8 years. There were more males in the YA group (71.3%) than in the OA group (58.5%, P < 0.001). There were 960 total cases of ACRN (1.4%), with 564 cases (0.9%) in the YA group and 396 cases (3.7%) in the OA group. The prevalence of CRC was also more frequent in the OA group (0.3%) than in the YA group (0.1%). Baseline characteristics of male and female subjects are described in Supplementary Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 70428 subjects n (%)

| Total | < 50 yr | ≥ 50 yr | P value | |

| (n = 70428) | (n = 59782) | (n = 10646) | ||

| Age (year, mean ± SD) | 41.6 ± 8.3 | 38.9 ± 5.3 | 56.5 ± 5.8 | < 0.001 |

| Sex | < 0.001 | |||

| Male | 48868 (69.4) | 42644 (71.3) | 6244 (58.5) | |

| Female | 21560 (30.6) | 17138 (28.7) | 4422 (41.5) | |

| BMI (kg/m2, mean ± SD) | 23.8 ± 3.1 | 23.8 ± 3.2 | 24.1 ± 2.8 | < 0.001 |

| Obesity1 | 23658 (33.6) | 19955 (33.4) | 3703 (34.8) | 0.005 |

| Smoking | < 0.001 | |||

| Never | 38955 (55.3) | 33071 (55.3) | 5884 (55.3) | |

| Former | 11480 (16.3) | 9610 (16.1) | 1870 (17.6) | |

| Current | 19993 (28.4) | 17101 (28.6) | 2892 (27.2) | |

| Alcohol intake | < 0.001 | |||

| No | 22090 (31.4) | 18517 (31.0) | 3573 (33.6) | |

| Moderate | 46026 (65.4) | 39404 (65.9) | 6622 (62.2) | |

| Heavy2 | 2312 (3.3) | 1861 (3.1) | 451 (4.2) | |

| CRC family history | 2779 (3.9) | 2111 (3.5) | 668 (6.3) | < 0.001 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 113.3 ± 13.0 | 113.0 ± 12.9 | 115.0 ± 13.7 | < 0.001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 72.6 ± 9.6 | 72.3 ± 9.5 | 74.1 ± 9.8 | < 0.001 |

| HTN-R3 | 23871 (33.9) | 19227 (32.2) | 4644 (43.6) | < 0.001 |

| DM-R4 | 16886 (24.0) | 11983 (20.0) | 3718 (34.9) | < 0.001 |

| Regular exercise5 | 38379 (54.5) | 33398 (55.9) | 4981 (46.8) | 0.000 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 93.6 ± 14.8 | 92.9 ± 13.7 | 97.7 ± 19.2 | < 0.001 |

| Insulin (μIU/mL) | 5.3 ± 5.1 | 5.1 ± 3.3 | 6.2 ± 10.5 | < 0.001 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.7 ± 0.5 | 5.6 ± 0.5 | 5.8 ± 0.7 | < 0.001 |

| Total-C (mg/dL) | 199.8 ± 34.7 | 198.6 ± 34.3 | 206.4 ± 36.2 | < 0.001 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 116.0 ± 76.3 | 115.3 ± 76.7 | 119.5 ± 73.8 | < 0.001 |

| Triglyceride ≥ 150 mg/dL | 15456 (21.9) | 12957 (21.7) | 2499 (23.5) | < 0.001 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 55.1 ± 13.8 | 55.2 ± 13.8 | 54.8 ± 13.8 | 0.003 |

| HDL-C abnormality6 | 10901 (15.5) | 8727 (14.6) | 2174 (20.4) | < 0.001 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 124.9 ± 32.0 | 124.1 ± 31.7 | 129.0 ± 33.1 | < 0.001 |

| CEA (ng/mL) | 1.62 ± 1.61 | 1.58 ± 1.61 | 1.83 ± 1.58 | < 0.001 |

| ACRN7 | 960 (1.4) | 564 (0.9) | 396 (3.7) | < 0.001 |

| CRC | 54 (0.1) | 25 (0.1) | 29 (0.3) | < 0.001 |

BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2;

More than 4 times per week as heavy;

Elevated blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg or use of antihypertensive medications;

Fasting plasma glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL or hemoglobin A1c ≥ 6.5%, or use of diabetes medications;

More than once per week;

HDL-C < 40 mg/dL for men or < 50 mg/dL for women;

ACRN was defined as a polyp size of ≥ 10 mm in diameter, polyp with any component of villous histology, high-grade dysplasia, or invasive cancer. SD: Standard deviation; BMI: Body mass index; CRC: Colorectal cancer; SBP: Systolic blood pressure; DBP: Diastolic blood pressure; HTN-R: Hypertension-related factors; DM-R: Diabetes mellitus-related factors; HbA1c: Hemoglobin A1c; Total-C: Total cholesterol; HDL-C: High-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; LDL-C: Low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; CEA: Carcinoembryonic antigen; ACRN: Advanced colorectal neoplasm.

ORs were calculated for each risk factors for ACRN in YA subjects (Table 2). Even in the YA group, age (OR = 1.08, 95%CI: 1.07-1.10, P < 0.001) was related with increased risk of ACRN. Risk was also increased in males (OR = 1.26, 95%CI: 1.02-1.55, P < 0.001) and current smokers (OR = 1.37, 95%CI: 1.15-1.63, P < 0.001). A family history of CRC (OR = 1.46, 95%CI: 1.01-2.10, P = 0.044) was also related with ACRN. Metabolic factors significantly affected ACRN development. Subject with DM-related factors (OR = 1.27, 95%CI: 1.06-1.54, P = 0.012), obesity (OR = 1.23, 95%CI: 1.03-1.47, P = 0.021) and serum LDL-C levels (OR = 1.01, 95%CI: 1.01-1.02, P = 0.006) increased risk of ACRN. Serum CEA level (OR = 1.04, 95%CI: 1.01-1.09, P = 0.031) was also related with the development for ACRN. The risk factors of ACRN in the YA group were also analyzed by sex (Table 3). In females, only age (OR = 1.08, 95%CI: 1.04-1.11, P < 0.001) and serum CEA levels (OR = 1.12, 95%CI: 1.02-1.23, P = 0.023) were related with ACRN. However, in males, age (OR = 1.09, 95%CI: 1.07-1.10, P < 0.001), current smoking (OR = 1.54, 95%CI: 1.27-1.87, P < 0.001), CRC family history (OR = 1.58, 95%CI: 1.06-2.36, P = 0.026), DM-related factors (OR = 1.34, 95%CI: 1.09-1.65, P = 0.005), obesity (OR = 1.24, 95%CI: 1.02-1.50, P = 0.028), serum LDL-C level (OR = 1.01, 95%CI: 1.01-1.02, P = 0.008) and serum CEA level (OR = 1.03, 95%CI: 1.01-1.05, P = 0.014) related with ACRN.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of risk factors for the development of advanced colorectal neoplasm in subjects under 50

| n (%) | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Age | 564/59782 (0.9) | 1.08 | 1.07-1.10 | < 0.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 123/17138 (0.7) | Reference | ||

| Male | 441/42644 (1.0) | 1.26 | 1.02-1.55 | 0.036 |

| Smoking | ||||

| Never/former | 358/42681 (0.8) | Reference | ||

| Current | 206/17101 (1.2) | 1.37 | 1.15-1.63 | < 0.001 |

| CRC family history | ||||

| No | 533/57671 (0.9) | Reference | ||

| Yes | 31/2111 (1.5) | 1.46 | 1.01-2.10 | 0.044 |

| DM-R | ||||

| No | 405/47799 (0.8) | Reference | ||

| Yes | 159/11983 (1.3) | 1.27 | 1.06-1.54 | 0.012 |

| Obesity | ||||

| No | 327/39827 (0.8) | Reference | ||

| Yes | 237/19955 (1.2) | 1.23 | 1.03-1.47 | 0.021 |

| LDL-C | 564/59782 (0.9) | 1.01 | 1.01-1.02 | 0.006 |

| CEA | 564/59782 (0.9) | 1.04 | 1.01-1.09 | 0.031 |

Adjusted for age, sex, smoking, alcohol, obesity (body mass index ≥ 25 kg/m2), triglyceride ≥ 150 mg/dL, HDL-C abnormality (HDL-C < 40 mg/dL for men or < 50 mg/dL for women), LDL-C, DM-R (fasting plasma glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL or hemoglobin A1c ≥ 6.5%, or use of diabetes medications), HTN-R (elevated blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg or use of antihypertensive medications), insulin, regular exercise, CRC family history and CEA. OR: Odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval; CRC: Colorectal cancer; DM-R: Diabetes mellitus-related factors; HTN-R: Hypertension-related factors; CEA: Carcinoembryonic antigen; LDL-C: Low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; HDL-C: High-density lipoprotein-cholesterol.

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of risk factors for the development of advanced colorectal neoplasm in subjects under 50 according to sex

| n (%) | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Female (n = 17138) | ||||

| Age | 123/17138 (0.7) | 1.08 | 1.04-1.11 | < 0.001 |

| CEA | 123/17138 (0.7) | 1.12 | 1.02-1.23 | 0.023 |

| Male (n = 42644) | ||||

| Age | 441/42644 (1.0) | 1.09 | 1.07-1.10 | < 0.001 |

| Smoking | ||||

| Never/former | 255/29005 (0.9) | Reference | ||

| Current | 186/13639 (1.4) | 1.54 | 1.27-1.87 | < 0.001 |

| CRC family history | ||||

| No | 415/41174 (1.0) | Reference | ||

| Yes | 26/1470 (1.8) | 1.58 | 1.06-2.36 | 0.026 |

| DM-R | ||||

| No | 300/32967 (0.9) | Reference | ||

| Yes | 141/9677 (1.5) | 1.34 | 1.09-1.65 | 0.005 |

| Obesity | ||||

| No | 226/25027 (0.9) | Reference | ||

| Yes | 215/17617 (1.2) | 1.24 | 1.02-1.50 | 0.028 |

| LDL-C | 441/42644 (1.0) | 1.01 | 1.01-1.02 | 0.008 |

| CEA | 441/42644 (1.0) | 1.03 | 1.01-1.05 | 0.014 |

Adjusted for age, sex, smoking, alcohol, obesity (body mass index ≥ 25 kg/m2), abdominal obesity (waist circumference ≥ 90 cm for men or ≥ 85 cm for women), triglyceride ≥ 150 mg/dL, HDL-C abnormality (HDL-C < 40 mg/dL for men or < 50 mg/dL for women), LDL-C, DM-R (fasting plasma glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL or hemoglobin A1c ≥ 6.5%, or use of diabetes medications), HTN-R (elevated blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg or use of antihypertensive medications), insulin, regular exercise, CRC family history and CEA. OR: Odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval; CRC: Colorectal cancer; DM-R: Diabetes mellitus-related factors; HTN-R: Hypertension-related factors; CEA: Carcinoembryonic antigen; LDL-C: Low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; HDL-C: High-density lipoprotein-cholesterol.

In the OA group, age (OR = 1.08, 95%CI: 1.06-1.09, P < 0.001) and male sex (OR = 2.12, 95%CI: 1.68-2.68, P < 0.001) were also significantly related with ACRN. ACRN was increased in smokers (OR = 1.38, 95%CI: 1.12-1.71, P = 0.003) and obese subjects (OR = 1.34, 95%CI: 1.09-1.65, P = 0.005). Serum CEA levels (OR = 1.05, 95%CI: 1.01-1.09, P = 0.022) also related with ACRN (Table 4). Risk factors for ACRN in the OA group by sex were also assessed (Table 5). In females, only age (OR = 1.04, 95%CI: 1.01-1.08, P = 0.006) was related with ACRN. In males, age (OR = 1.09, 95%CI: 1.07-1.11, P < 0.001), current smoking (OR = 1.44, 95%CI: 1.12-1.79, P = 0.004), obesity (OR = 1.41, 95%CI: 1.11-1.79, P = 0.005) and serum CEA level (OR = 1.04, 95%CI: 1.01-1.08, P = 0.023) related with ACRN. Whereas, family history of CRC showed a protective effect (OR = 0.55, 95%CI: 0.31-0.96, P = 0.037).

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of risk factors for the development of advanced colorectal neoplasm in subjects over 50

| n (%) | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Age | 396/10646 (3.7) | 1.08 | 1.06-1.09 | < 0.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 102/4422 (2.3) | Reference | ||

| Male | 294/6224 (4.7) | 2.12 | 1.68-2.68 | < 0.001 |

| Smoking | ||||

| Never/former | 261/7754 (3.4) | Reference | ||

| Current | 135/2892 (4.7) | 1.38 | 1.12-1.71 | 0.003 |

| Obesity | ||||

| No | 229/6943 (3.3) | Reference | ||

| Yes | 167/3703 (4.5) | 1.34 | 1.09-1.65 | 0.005 |

| CEA | 396/10646 (3.7) | 1.05 | 1.01-1.09 | 0.022 |

Adjusted for age, sex, smoking, alcohol, obesity (body mass index ≥ 25 kg/m2), triglyceride ≥ 150 mg/dL, HDL-C abnormality (HDL-C < 40 mg/dL for men or < 50 mg/dL for women), LDL-C, DM-R (fasting plasma glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL or hemoglobin A1c ≥ 6.5%, or use of diabetes medications), HTN-R (elevated blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg or use of antihypertensive medications), insulin, regular exercise, CRC family history and CEA. OR: Odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval; CRC: Colorectal cancer; DM-R: Diabetes mellitus-related factors; HTN-R: Hypertension-related factors; CEA: Carcinoembryonic antigen; LDL-C: Low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; HDL-C: High-density lipoprotein-cholesterol.

Table 5.

Multivariate analysis of risk factors for the development of advanced colorectal neoplasm in subjects over 50 according to sex

| n (%) | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Female (n = 4422) | ||||

| Age | 102/4422 (2.3) | 1.04 | 1.01-1.08 | 0.006 |

| Male (n = 6224) | ||||

| Age | 294/6224 (4.7) | 1.09 | 1.07-1.11 | < 0.001 |

| Smoking | ||||

| Never/former | 188/4410 (4.3) | Reference | ||

| Current | 106/1814 (5.8) | 1.44 | 1.12-1.79 | 0.004 |

| Obesity | ||||

| No | 164/3833 (4.3) | Reference | ||

| Yes | 130/2391 (5.4) | 1.41 | 1.11-1.79 | 0.005 |

| CRC family history | ||||

| No | 281/5796 (4.8) | Reference | ||

| Yes | 13/438 (3.0) | 0.55 | 0.31-0.96 | 0.037 |

| CEA | 294/6224 (4.7) | 1.04 | 1.01-1.08 | 0.023 |

Adjusted for age, smoking, alcohol, obesity (body mass index ≥ 25 kg/m2), triglyceride ≥ 150 mg/dL, HDL-C abnormality (HDL-C < 40 mg/dL for men or < 50 mg/dL for women), LDL-C, DM-R (fasting plasma glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL or hemoglobin A1c ≥ 6.5%, or use of diabetes medications), HTN-R (elevated blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg or use of antihypertensive medications), insulin, regular exercise, CRC family history and CEA. OR: Odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval; CRC: Colorectal cancer; DM-R: Diabetes mellitus-related factors; HTN-R: Hypertension-related factors; CEA: Carcinoembryonic antigen; LDL-C: Low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; HDL-C: High-density lipoprotein-cholesterol.

DISCUSSION

The present study evaluated different risk factors for ACRN according to age and sex groups. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to compare laboratory factors, anthropometric data and life habits between the age groups in a large population when evaluating the risk of ACRN.

Many studies have evaluated age as an important risk factor for development of CRA and CRC[16-18]. In the present study, the prevalence of ACRN and CRC were significantly greater in the OA group (3.7% and 0.3%, respectively) than in the YA group (0.9% and 0.1%, respectively). Age was also an important risk factor for ACRN in the OA and YA groups and in the male and female subgroups. In particular, it was the only risk factor for ACRN in the female subgroup of the OA group. Therefore, age should be regarded as a critical factor in screening colonoscopy. The authors considered screening colonoscopies beginning at 50 years of age to be appropriate and acceptable.

In the present study, male sex was revealed as a risk factor for ACRN regardless of age group, with an adjusted OR with 2.12 in the OA group. Previous studies reported that male sex increased the risk of CRA[17,19,20]. and this association was also found for ACRN[21]. Smoking was associated with significantly increased risk of ACRN in the modifiable factors through life style modification and this result was consistent with previous studies[22,23]. In the present study, this relationship was evaluated regardless of age groups, especially in males. The effect of smoking on ACRN according to sex was not clear. A previous study reported that smoking affected females more[24], while other studies reported the effect of smoking on CRC was similar in both sexes[25] or greater in males[18]. Whereas, alcohol consumption was not associated with ACRN in our study. The effect of alcohol on the development of ACRN is controversial[26,27]. Further study is required.

A family history of CRC within first degree relatives is a well-known risk factor for ACRN[28,29]. In the present study, CRC family history was evaluated as a risk factor of ACRN in the YA group, whereas it showed a protective effect in the OA group. This was due to the fact that this study targeted subjects at their first screening colonoscopy. In the OA group, high risk subjects with a familial history of CRC were likely excluded because they had started screening colonoscopies in their forties. The authors do not conclude that familial CRC history is protective in older adults; however, early screening colonoscopies may be protective in patients younger than 50 with a family history of CRC.

There are clear associations between ACRN and metabolic syndromes and obesity[30-33]. Obesity was related with an increased risk of ACRN in both the OA and YA groups in the present study. However, in cases of MetA, DM-related factors and LDL-C increased the risk of ACRN only in the YA group. These significant associations were not evaluated in the OA group. Especially, the authors evaluated the risks of ACRN in subjects with documented DM or dyslipidemia as well in subjects with early-stage MatA using NCEP-ATP III criteria. There were no associations between hypertriglyceridemia or HDL-C abnormalities and ACRN in the YA group. Subjects under 50 with metabolic syndrome or any glucose or LDL-C metabolism abnormality should be receive special attention. It was reported that metabolic syndrome and smoking significantly impacted both the prevalence of colorectal neoplasms and the diagnostic yield of screening tests in men aged 40 to 49 years[34]. The reasons why younger subjects were more susceptible to abnormal glucose or lipid metabolism were not clearly evaluated. It was reported that obesity and metabolic syndrome affected on CRA in the young subjects[35], however, a study which was performed in South Korea was also evaluated that the effect of obesity and metabolic syndrome disappeared in the subjects with older than 50 years[36]. The reasons for the greater effect of obesity and MetA on the YA group require further evaluation.

The prevalence of ACRN was 1.0% in females, which was lower than in males (1.5%). In the OA group, 2.3% of females and 4.7% of males had ACRNs, while in the YA group, 0.7% of females and 1.0% of males had ACRN. In the present study, the effects of obesity and MetA on ACRN were evaluated only in males, however, there was no such relationship in females. The mean BMIs of the present study were much lower in females (21.9 ± 3.0 kg/m2 in the YA group and 23.7 ± 3.0 kg/m2 in the OA group) than in males (24.6 ± 2.9 kg/m2 in the YA group and 24.3 ± 2.6 kg/m2 in the OA group). Most serum markers were higher in males than in females. These absolute values of BMI and serum markers might cause differences between females and males, although the details of these effects remain unclear. Previous studies reported that BMI or MetA was associated with increased risk of CRC or CRA in males, whereas this association was generally weaker in females[37-41]. Generally, these differences are considered to be related to the hormonal status of premenopausal women. Preclinical data support a role for estrogen and its receptors in the initiation and progression of CRC and estrogen can exert protective effects through estrogen receptor β[42]. CRC risk increased in subjects with MetA[43], and adipokines can link obesity with CRC risk in postmenopausal women[44]. Whereas, recent studies found significant associations with the risk of CRC development even in postmenopausal women[45]. Further studies are needed to clarify the differences in risk by sex.

The present study had several limitations. Around 20% of initial subject in YA group and around 30% of initial subject in OA group were excluded because they had previous colonoscopy. The authors targeted subjects at their first screening colonoscopy, so high risk subjects with a family history of CRC in the OA group might be missed. These could effect on the study as a selection bias. However, the present study aimed to assess the average risk of ACRN. Subjects who had previous colonoscopy is heterogenous group including subjects with ACRN, subjects with low risk adenoma or subject with normal colonoscopy. It is also difficult to assess the result of previous colonoscopy relying on subject’s memory. Therefore, the authors excluded the subjects who had previous colonoscopy to prevent the heterogeneity of study subjects. Adenoma detection rate or the present study was 14.2% and the rate was slightly low when it was compared with recommended adenoma detection rate. However, the present study targeted subject who took first colonoscopy and the majority of subject were YA with under the age of 50. This could make adenoma detection rate relatively low. The cross-sectional study with a single ethnic group precludes our ability to assess causation. Data on smoking, alcohol intake and exercise were evaluated by simple questionnaires, not quantitatively. However, data collection was difficult because this was a large-scale population-based study. However, we collected various anthropometric measurements and metabolic laboratory factors which were frequently used in clinical practice for all study participants. This provides valuable risk factors, which are crucial for determining screening strategies.

The prevalence of ACRN is 5%-10% in Western countries[26,28], however, it is only 1%-5% in Asia[17,36]. Therefore, clear targets for screening colonoscopy and ACRN evaluation are required in Asian populations. In the present study, age, male, current smoking, obesity and CEA were important risk factors for ACRN, despite the low prevalence. Furthermore, all study subjects were asymptomatic, of average risk, enrolled in a screening setting and were representative of our general screening target population. Especially, in the YA group, subject with family history of CRC or MetA including DM-related factor or increased LDL-C significantly increased the risk of ACRN. The authors enrolled almost 60000 subjects younger than 50 with a mean age of 38.9 ± 5.3 years, which was much younger than subjects in the previous studies. The authors recommend screening colonoscopies in subjects under 50 with specific risk factors. These results are meaningful because of the large YA population in this study.

In conclusion, risk factors for ACRN differed between the OA and YA groups. This study provides a valuable link between risk factors and colonoscopic findings according to age, which are crucial for determining screening strategies. Our findings suggest that more careful and aggressive screening should be considered for subjects with specific considerations, even younger than 50 years.

COMMENTS

Background

Development of advanced colorectal neoplasm (ACRN) is related with several risk factors. Evaluating the risk of ACRN is important for preventing the colorectal cancer. However, few studies evaluated different risk factor between young adults (YA, < 50 years) and older adults (OA, ≥ 50 years).

Research frontiers

To compare the risk of developing ACRN according to age in Koreans

Innovations and break through

The risks of ACRN differed based on age group. Age was an important risk factor for ACRN in both YA and OA groups. Metabolic abnormalities including diabetes mellitus (DM) related factors and serum level of low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C) were more related with increased risk of ACRN in the YA group.

Applications

Colorectal cancer (CRC) screening using colonoscopy was recommended after 50 years. The risks of ACRN differed based on age group. Different colonoscopic screening strategies are appropriate for particular subjects with risk factors for ACRN, even in subjects younger than 50 years.

Terminology

ACRN was defined as an adenoma ≥ 10 mm in diameter, adenoma with any component of villous histology, high-grade dysplasia, or invasive cancer.

Peer-review

The manuscript described the risk factors for ACRN in young Korean adults included age, male gender, current smoking, family history of CRC, DM, obesity, LDL-C and carcinoembryonic antigen. The sheer size of this study including 70000 patients who underwent colonoscopy probably warrants publication.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the Kangbuk Samsung Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Informed consent statement: This study can prejudice the study participants no more than minimal risk. Data which were used in this study were already acquired for report of the result to subjects who had examination and administration of the result. The present study could contribute to preventing the disease through interpretation and application of the results of health care examination. There will be no risk to participants because this study will be analyzed retrospectively using only obtained data without additional administration of medicine, treatment or examination. Kangbuk Samsung Hospital institutional review board exempted the written informed consent of the present study.

Conflict-of-interest statement: None of the authors have any conflicts of interest or financial arrangements that could potentially influence the described research.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: December 17, 2015

First decision: January 28, 2016

Article in press: March 2, 2016

P- Reviewer: Hsu CM, Wexner SD S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

References

- 1.Jung KW, Won YJ, Park S, Kong HJ, Sung J, Shin HR, Park EC, Lee JS. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality and survival in 2005. J Korean Med Sci. 2009;24:995–1003. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2009.24.6.995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goh LY, Leow AH, Goh KL. Observations on the epidemiology of gastrointestinal and liver cancers in the Asia-Pacific region. J Dig Dis. 2014;15:463–468. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park HW, Byeon JS, Yang SK, Kim HS, Kim WH, Kim TI, Park DI, Kim YH, Kim HJ, Lee MS, et al. Colorectal Neoplasm in Asymptomatic Average-risk Koreans: The KASID Prospective Multicenter Colonoscopy Survey. Gut Liver. 2009;3:35–40. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2009.3.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.St-Onge MP, Janssen I, Heymsfield SB. Metabolic syndrome in normal-weight Americans: new definition of the metabolically obese, normal-weight individual. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2222–2228. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.9.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, O’Brien MJ, Ho MN, Gottlieb L, Sternberg SS, Waye JD, Bond J, Schapiro M, Stewart ET. Randomized comparison of surveillance intervals after colonoscopic removal of newly diagnosed adenomatous polyps. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:901–906. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304013281301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brenner H, Kloor M, Pox CP. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2014;383:1490–1502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61649-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishihara R, Wu K, Lochhead P, Morikawa T, Liao X, Qian ZR, Inamura K, Kim SA, Kuchiba A, Yamauchi M, et al. Long-term colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality after lower endoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1095–1105. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin OS, Kozarek RA, Cha JM. Impact of sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: an evidence-based review of published prospective and retrospective studies. Intest Res. 2014;12:268–274. doi: 10.5217/ir.2014.12.4.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.JK Kim, YC Choi, JP Suh, IT Lee, EG Youk, DS Lee. Results of screening colonoscopy in asymptomatic average-risk Koreans at a community-based secondary hospital. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;41:266–272. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Austin H, Henley SJ, King J, Richardson LC, Eheman C. Changes in colorectal cancer incidence rates in young and older adults in the United States: what does it tell us about screening. Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:191–201. doi: 10.1007/s10552-013-0321-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, Andrews KS, Brooks D, Bond J, Dash C, Giardiello FM, Glick S, Johnson D, Johnson CD, Levin TR, Pickhardt PJ, Rex DK, Smith RA, Thorson A, Winawer SJ; American Cancer Society Colorectal Cancer Advisory Group; US Multi-Society Task Force; American College of Radiology Colon Cancer Committee. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1570–1595. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sung JJ, Lau JY, Young GP, Sano Y, Chiu HM, Byeon JS, Yeoh KG, Goh KL, Sollano J, Rerknimitr R, Matsuda T, Wu KC, Ng S, Leung SY, Makharia G, Chong VH, Ho KY, Brooks D, Lieberman DA, Chan FK; Asia Pacific Working Group on Colorectal Cancer. Asia Pacific consensus recommendations for colorectal cancer screening. Gut. 2008;57:1166–1176. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.146316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Region WHOWP. The Asia-pacific perspective: redefining obesity and its treatment. Sydney, Austrailia: Health Comunications Australia Pty Limit; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, Fruchart JC, James WP, Loria CM, Smith SC Jr; International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; Hational Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; International Association for the Study of Obesity. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120:1640–1645. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heitman SJ, Ronksley PE, Hilsden RJ, Manns BJ, Rostom A, Hemmelgarn BR. Prevalence of adenomas and colorectal cancer in average risk individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1272–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rundle AG, Lebwohl B, Vogel R, Levine S, Neugut AI. Colonoscopic screening in average-risk individuals ages 40 to 49 vs 50 to 59 years. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1311–1315. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choe JW, Chang HS, Yang SK, Myung SJ, Byeon JS, Lee D, Song HK, Lee HJ, Chung EJ, Kim SY, et al. Screening colonoscopy in asymptomatic average-risk Koreans: analysis in relation to age and sex. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1003–1008. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freedman AN, Slattery ML, Ballard-Barbash R, Willis G, Cann BJ, Pee D, Gail MH, Pfeiffer RM. Colorectal cancer risk prediction tool for white men and women without known susceptibility. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:686–693. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.4797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferlitsch M, Reinhart K, Pramhas S, Wiener C, Gal O, Bannert C, Hassler M, Kozbial K, Dunkler D, Trauner M, et al. Sex-specific prevalence of adenomas, advanced adenomas, and colorectal cancer in individuals undergoing screening colonoscopy. JAMA. 2011;306:1352–1358. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park DI, Kim YH, Kim HS, Kim WH, Kim TI, Kim HJ, Yang SK, Byeon JS, Lee MS, Jung IK, et al. Diagnostic yield of advanced colorectal neoplasia at colonoscopy, according to indications: an investigation from the Korean Association for the Study of Intestinal Diseases (KASID) Endoscopy. 2006;38:449–455. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-925227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong MC, Lam TY, Tsoi KK, Hirai HW, Chan VC, Ching JY, Chan FK, Sung JJ. A validated tool to predict colorectal neoplasia and inform screening choice for asymptomatic subjects. Gut. 2014;63:1130–1136. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stegeman I, de Wijkerslooth TR, Stoop EM, van Leerdam ME, Dekker E, van Ballegooijen M, Kuipers EJ, Fockens P, Kraaijenhagen RA, Bossuyt PM. Colorectal cancer risk factors in the detection of advanced adenoma and colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;37:278–283. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shin A, Hong CW, Sohn DK, Chang Kim B, Han KS, Chang HJ, Kim J, Oh JH. Associations of cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption with advanced or multiple colorectal adenoma risks: a colonoscopy-based case-control study in Korea. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174:552–562. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parajuli R, Bjerkaas E, Tverdal A, Selmer R, Le Marchand L, Weiderpass E, Gram IT. The increased risk of colon cancer due to cigarette smoking may be greater in women than men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:862–871. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parajuli R, Bjerkaas E, Tverdal A, Le Marchand L, Weiderpass E, Gram IT. Cigarette smoking and colorectal cancer mortality among 602,242 Norwegian males and females. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:137–145. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S58722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong MC, Lam TY, Tsoi KK, Chan VC, Hirai HW, Ching JY, Sung JJ. Predictors of advanced colorectal neoplasia for colorectal cancer screening. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46:433–439. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yeoh KG, Ho KY, Chiu HM, Zhu F, Ching JY, Wu DC, Matsuda T, Byeon JS, Lee SK, Goh KL, Sollano J, Rerknimitr R, Leong R, Tsoi K, Lin JT, Sung JJ; Asia-Pacific Working Group on Colorectal Cancer. The Asia-Pacific Colorectal Screening score: a validated tool that stratifies risk for colorectal advanced neoplasia in asymptomatic Asian subjects. Gut. 2011;60:1236–1241. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.221168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Regula J, Rupinski M, Kraszewska E, Polkowski M, Pachlewski J, Orlowska J, Nowacki MP, Butruk E. Colonoscopy in colorectal-cancer screening for detection of advanced neoplasia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1863–1872. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee SY, Shin A, Kim BC, Lee JH, Han KS, Hong CW, Sohn DK, Park SC, Chang HJ, Oh JH. Association between family history of malignant neoplasm with colorectal adenomatous polyp in 40s aged relative person. Cancer Epidemiol. 2014;38:623–627. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harriss DJ, Atkinson G, George K, Cable NT, Reilly T, Haboubi N, Zwahlen M, Egger M, Renehan AG. Lifestyle factors and colorectal cancer risk (1): systematic review and meta-analysis of associations with body mass index. Colorectal Dis. 2009;11:547–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ben Q, An W, Jiang Y, Zhan X, Du Y, Cai QC, Gao J, Li Z. Body mass index increases risk for colorectal adenomas based on meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:762–772. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jinjuvadia R, Lohia P, Jinjuvadia C, Montoya S, Liangpunsakul S. The association between metabolic syndrome and colorectal neoplasm: systemic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:33–44. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182688c15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bardou M, Barkun AN, Martel M. Obesity and colorectal cancer. Gut. 2013;62:933–947. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang LC, Wu MS, Tu CH, Lee YC, Shun CT, Chiu HM. Metabolic syndrome and smoking may justify earlier colorectal cancer screening in men. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:961–969. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gunter MJ, Leitzmann MF. Obesity and colorectal cancer: epidemiology, mechanisms and candidate genes. J Nutr Biochem. 2006;17:145–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hong SN, Kim JH, Choe WH, Han HS, Sung IK, Park HS, Shim CS. Prevalence and risk of colorectal neoplasms in asymptomatic, average-risk screenees 40 to 49 years of age. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:480–489. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yun KE, Chang Y, Jung HS, Kim CW, Kwon MJ, Park SK, Sung E, Shin H, Park HS, Ryu S. Impact of body mass index on the risk of colorectal adenoma in a metabolically healthy population. Cancer Res. 2013;73:4020–4027. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adams KF, Leitzmann MF, Albanes D, Kipnis V, Mouw T, Hollenbeck A, Schatzkin A. Body mass and colorectal cancer risk in the NIH-AARP cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166:36–45. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ma Y, Yang Y, Wang F, Zhang P, Shi C, Zou Y, Qin H. Obesity and risk of colorectal cancer: a systematic review of prospective studies. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53916. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu CS, Hsu HS, Li CI, Jan CI, Li TC, Lin WY, Lin T, Chen YC, Lee CC, Lin CC. Central obesity and atherogenic dyslipidemia in metabolic syndrome are associated with increased risk for colorectal adenoma in a Chinese population. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:51. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-10-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li H, Yang G, Xiang YB, Zhang X, Zheng W, Gao YT, Shu XO. Body weight, fat distribution and colorectal cancer risk: a report from cohort studies of 134255 Chinese men and women. Int J Obes (Lond) 2013;37:783–789. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Edvardsson K, Ström A, Jonsson P, Gustafsson JÅ, Williams C. Estrogen receptor β induces antiinflammatory and antitumorigenic networks in colon cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25:969–979. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Agnoli C, Grioni S, Sieri S, Sacerdote C, Vineis P, Tumino R, Giurdanella MC, Pala V, Mattiello A, Chiodini P, et al. Colorectal cancer risk and dyslipidemia: a case-cohort study nested in an Italian multicentre cohort. Cancer Epidemiol. 2014;38:144–151. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ho GY, Wang T, Gunter MJ, Strickler HD, Cushman M, Kaplan RC, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Xue X, Rajpathak SN, Chlebowski RT, et al. Adipokines linking obesity with colorectal cancer risk in postmenopausal women. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3029–3037. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kabat GC, Heo M, Wactawski-Wende J, Messina C, Thomson CA, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Rohan TE. Body fat and risk of colorectal cancer among postmenopausal women. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24:1197–1205. doi: 10.1007/s10552-013-0199-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]