Abstract

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) is a member of the PPARs, which are transcription factors of the steroid receptor superfamily. PPARγ acts as an important molecule for regulating energy homeostasis, modulates the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, and is reciprocally regulated by HPG. In the human, PPARγ protein is highly expressed in ejaculated spermatozoa, implying a possible role of PPARγ signaling in regulating sperm energy dissipation. PPARγ protein is also expressed in Sertoli cells and germ cells (spermatocytes). Its activation can be induced during capacitation and the acrosome reaction. This mini-review will focus on how PPARγ signaling may affect fertility and sperm quality and the potential reversibility of these adverse effects.

Keywords: fertilization, hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, insulin resistance, leptin, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, sperm physiology, spermatogenesis, spermatozoa

INTRODUCTION

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) was originally named for its ability to induce hepatic peroxisome proliferation in mice in response to xenobiotic stimuli.1 It belongs to the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily of ligand-activated transcription factors. The PPAR family consists of three primary subtypes, PPARγ, PPARβ/δ and PPARγ, which are encoded by separate genes.2 These receptors play a central role in the physiological processes that have an impact on lipid homeostasis, inflammation, adipogenesis, reproduction, wound healing, and carcinogenesis.3,4,5 PPARγ is also implicated in a wide variety of cellular functions and regulates the expression of gene networks required for cell proliferation, differentiation, morphogenesis and metabolic homeostasis. It is possible to hypothesize that PPARγ potentially activates lipogenic genes and adipocyte differentiation.6,7,8 PPARγ is highly expressed in adipose tissue9 and it is necessary for adipocyte differentiation and transformation of many nonadipogenic cell lines into adipocyte-like cells. PPARγ is also an important transcriptional regulator that modulates cellular glucose and lipid metabolism.10 Intensive studies and compelling evidence have demonstrated that PPARγ is a link between energy metabolism and reproduction, as in male infertility because of obesity, which is frequently associated with insulin resistance.11

Thorough studies have demonstrated a close link between energy status and reproductive functions.12 In mice, loss of the PPARγ gene in oocytes and granulosa cells results in impaired fertility.13 Moreover, Aquila et al. have demonstrated that human spermatozoa express PPARγ protein and investigated its functions.14 Recently, repetition of thorough studies have indicated that sperm cells express various receptor types,15,16 and also produce their ligands, suggesting that an autocrine short loop may modulate sperm cell's function independently by systemic regulation.17,18 Nevertheless, it is necessary for spermatozoa to regulate their metabolism to affect the changes in signaling pathways encountered during their life. However, the mechanisms underlying the signaling events associated with the change in sperm energy metabolism are, to date, poorly understood.

Here, we will briefly review the mechanisms of sperm physiology, determining whether PPARγ signaling affects sperm capacitation and the possible targets of therapy of male infertility. PPARγ agonists may be used in artificial insemination or other biotechnologies, including cryopreservation.

EXPRESSION AND PUTATIVE ROLES OF PEROXISOME PROLIFERATOR-ACTIVATED RECEPTOR GAMMA SIGNALING IN THE REPRODUCTIVE TISSUES

Hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis

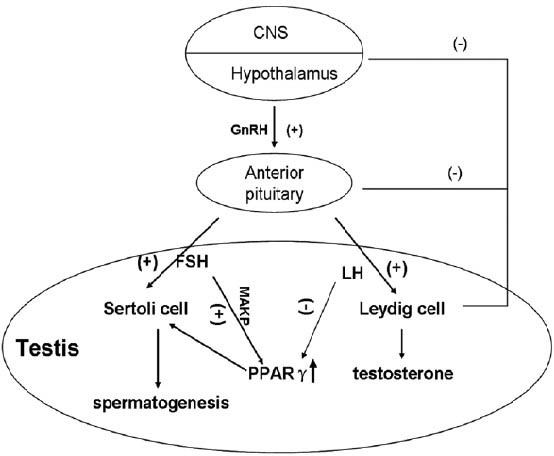

Early studies elucidated that adenoma cells can suppress the proliferation of pituitary cells,19 and the administration of thiazolidinediones (TZDs) inhibits the development of pituitary adenomas in mice and man. Furthermore, in the pituitary gland of mice, the expression of PPARγ is reduced by 54% after 24 h of food restriction.20 In the hypothalamus, PPARγ regulates a variety of molecules involved in energy homeostasis,20 mainly playing a role in temperature regulation through its natural ligand 15-deoxy-delta12, 14-prostaglandin J2 (PGJ2), which is secreted into cerebrospinal fluid.21 It is still unclear whether the effect of PPARγ on reproductive function is mediated by this signal pathway. Some pituitary tumors secrete hormones such as prolactin (PRL) and growth hormone (GH). In most of PRL- and GH-secreting pituitary tumors, these hormones control tumor growth or induce tumor shrinkage.22 Moreover, pituitary PPARγ is abundantly expressed in human PRL-, GH-secreting, and nonfunctioning pituitary tumors.19 Conditional knockout of PPARγ in pituitary gonadotrophs causes an increase in luteinizing hormone levels in female mice, a decrease in follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) in male mice, and a fertility defect in knockout mice characterized by reduced litter size.23 Moreover, it has been reported that PPARγ functions are regulated by FSH through mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways (Figure 1).24 Thus, it is suggested that PPARγ signaling participates in the regulation of pituitary hormones.

Figure 1.

PPARγ functions in hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. Pulsatile GnRH production signals gonadotroph cells in the anterior pituitary to produce FSH and LH that then act on the testis to regulate spermatogenic potential. FSH up-regulates the expression of PPARγ through MAPK signaling pathways while LH inhibits the function of PPARγ via various pathways. High expression of testosterone suppresses the secretion of LH by negative feedback, providing a relatively persistent high-expression of PPARγ. PPARγ: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma; FSH: follicle-stimulating hormone; LH: luteinizing hormone; MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase.

In the testis, the PPARs are expressed in both somatic and germ cells.25 PPARα and PPARβ are widely expressed in the interstitial Leydig cells and the seminiferous tubule cells (Sertoli and germ cells),26 whereas, PPARγ is believed to be restricted to Sertoli cells.27 Sertoli cells are the first cells to differentiate recognizably in the undifferentiated fetal gonad, an event, which enables seminiferous cord formation, prevention of germ-cell entry into meiosis, differentiation, and function of Leydig cells.28 During puberty, Sertoli cells also play vital roles in supporting spermatogenesis. Without the physical and metabolic support of Sertoli cells, germ-cell differentiation, meiosis and transformation into spermatozoa would not occur.29 Moreover, Thomas et al. have recently detected PPARγ mRNA in the germ cells (spermatocytes).30 It may be that PPARγ signaling regulates the pattern of expression of key lipid and glucose metabolic genes in the Sertoli cells.

Spermatogenesis

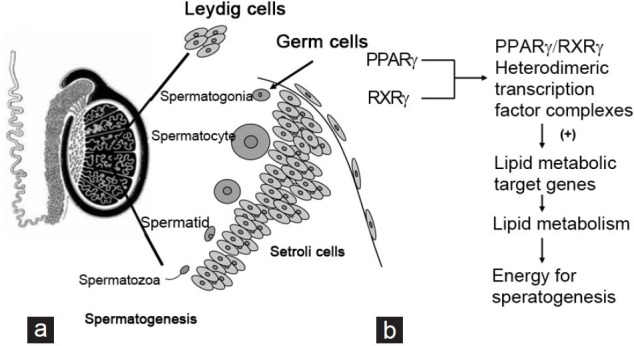

Spermatogenesis is the successful transformation of round spermatids into the complex structure of the spermatozoon (Figure 2a).31 However, the physiological demands of reproduction are energetically costly and mating behavior and physiological responses are inhibited when fuel reserves or food intake is limited. Indeed, inadequate metabolic fuel utilization is the common factor of nutritional infertility.32 Of the sources of stored energy that can be tapped for fuel reproductive energy requirements, the largest depot is white adipose tissue (WAT), which is primarily composed of white adipocytes that store lipid fuels as triacylglycerols.33,34,35 Epididymal WAT (EWAT) is necessary for normal spermatogenesis and could produce a locally acting factor responsible for maintaining spermatogenesis since a decrease in EWAT causes a disturbance in spermatogenesis.34,36 However, removal of comparable amounts of WAT from other sites (inguinal) shows no effect, disproving the idea that the effect is due to a decreased energy supply or the need for some minimal amount of fat.37 It has been suggested that it might be due to the presence of a local, but currently unidentified, growth or nutritive factor from EWAT that promotes spermatogenesis. PPARγ, known as one of the master regulators in adipogenesis, is also developmentally expressed both in differentiating germ and Sertoli cells,27,30 where it is involved in regulating the patterns of expression of key lipid metabolic genes in Sertoli cells.30 It is also indicated that PPARγ signaling plays an important role in spermatogenesis.30

Figure 2.

Expression patterns of PPARg shows in the testis. (a) In the testis, PPARγ protein is detected at high expression in Sertoli cells and weak expression in spermatocytes. The names of cells expressing PPARγ are underlined. (b) PPARγ forms obligate heterodimers with RXRγ for regulation of lipid metabolic target genes, providing energy for spermatogenesis. PPARγ: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma; RXRγ: retinoid X receptor gamma.

Mechanisms of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma signaling in spermatogenesis

The PPARs form obligate heterodimers with the retinoid X receptors (RXRs) to produce functional transcription factors that are involved in transactivation of several key genes during energy homeostasis and cellular differentiation (Figure 2b).30,38,39,40 TZDs, the synthetic ligands of PPARs, have been demonstrated to modify PPAR-mediated transcriptional activation of a number of key genes involved in energy homeostasis.41 Furthermore, Thomas et al. have demonstrated that PPAR and RXR transcripts encoding members of the PPAR and RXR nuclear receptor family reach maximum levels of expression in the germ cells during the early meiotic stages of spermatogenesis.30 PPARγ levels peak at a slightly later stage of spermatogenesis in leptotene/zygotene spermatocytes, concomitant with increased levels of RXRβ and RXRγ expression. PPARγ/RXRγ heterodimeric transcription factor complexes, the predominant transcripts expressed in mature Sertoli cells, up-regulate lipid metabolic target genes in Sertoli cells, providing them with enough energy to support spermatogenesis. Infertility occurs if there is an interruption of the spermatogenic program.42,43 In addition, male fertility can be compromised by inactivation of genes involved in lipid metabolism.44 In summary, except for its role in spermatogenesis, PPARγ participates in fertilization by supporting energy provision.

PEROXISOME PROLIFERATOR-ACTIVATED RECEPTOR GAMMA ACTION IN FERTILIZATION

Roles of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in fertilization

Fertilization is a complex program of biochemical changes that spermatozoa undergo in the female reproductive tract. Once capacitated, the spermatozoon can bind to the zona pellucida of the oocyte and undergo the acrosome reaction (AR), a process that enables sperm penetration and fertilization of the oocyte.45 Some intracellular changes, including an increase in cholesterol efflux, a rise in membrane fluidity, an increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration,46,47 and actin polymerization,48,49 have been considered to be the acceptable markers of capacitation. PPARγ agonist was able to elevate the functional maturation of sperm by evaluating its action on capacitation.50 Recent research has demonstrated that PPARγ is expressed by ejaculated spermatozoa of humans and pigs, improving their motility, capacitation, AR, survival and metabolism.14,50

Roles of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in infertility

Infertility is the inability to conceive after 12 months of regular, unprotected intercourse,51 which is a problem of public health importance in China and many other developing nations because of its high prevalence and its serious social implications for affected couples and families. Epidemiological studies have confirmed that infertility affects approximately 5% of newly married couples in Shanghai, China. Under infertility treatment, about 60% of couples subsequently have a higher chance of having children than the untreated.52 Recently, reports have asserted that sperm concentrations have been identified a potential decline over the past several decades, which may result in the decline in male fertility; however, the causes and extent of declining sperm quality and fertility remain unknown in most cases. Beyond the growing burden of disease, male infertility, associated with a high cost of care, generates significant psychosocial and marital stress. In addition, paternal health cues can be passed to the next generation, with male age associated with an increase in autistic spectrum disorders53 and environmental exposures associated with increases in incidences of childhood diseases.54,55 Likewise, there is now evidence that paternal infertility may be transferred to the offspring, including metabolic diseases.56 As a result, several factors relating to general health and well-being, such as diet,57 exercise,58 obesity,59 and psychological stress,60,61 have been extensively studied for their effects on male reproductive potential. Special attention has been paid to the connections between obesity and sperm function. It is of great importance to find out the causes of declining sperm quality and fertility, which adversely affect human reproduction. It is a matter of great concern triggering large-scale studies into its causes and possibilities for prevention.

There is now emerging evidence that male obesity has a negative impact on male reproductive potential not only by reducing sperm quality, but in particular by altering the physical and molecular structure of testicular germ cells and ultimately mature spermatozoa.59 Meanwhile, hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia are common in obese individuals and are constant confounding factors in many rodent studies of male obesity.62,63,64 Apart from these, the fuel sensors glucose, insulin65,66 and leptin67,68,69 are known to be directly involved in the regulation of fertility at each level of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis.70 The discovery of the PPAR family of transcription factors has revealed a link between lipid or glucose availability and long-term metabolic adaptation.70 Historically, the roles of PPARγ have been associated with preadipocyte expansion and differentiation.71 PPARγ mainly plays key roles in the regulation of cellular lipid metabolism, redox status and organelle differentiation in adipose tissue and other organs such as the prostate.72,73 Therefore, it remains plausible that PPARγ participates in the regulation of male reproductive function, by reducing sperm motility and inducing male infertility.

Roles of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in sperm capacitation and sperm metabolism

Sperm capacitation is an intricate program in which a myriad of events take place with the result that spermatozoa can penetrate and fertilize the oocyte. The bioenergetics of sperm capacitation is poorly understood despite its fundamental role in sustaining the biochemical and molecular events occurring during gamete activation. Adenosine triphosphate is synthesized by spermatozoa through either aerobic or anaerobic metabolic pathways. Santoro et al. demonstrated that in the majority of spermatozoa, PPARγ was expressed in the apical region of the head, in the subacrosomial region and prevalently in the midpiece, while the signaling was almost absent from the tail. However, in capacitated spermatozoa, the location of the receptor mirrors that observed in uncapacitated sperm cells.50 It has been confirmed that PGJ2, an agonist of PPARγ, increases the viability of spermatozoa, whereas all these events are reduced by the irreversible PPARγ antagonist GW9662,50 confirming the involvement of PPARγ in sperm viability. Meanwhile, PPARγ antagonist GW was able to attenuate the functional maturation of spermatozoa by evaluating its action on capacitation which has been correlated with functional and biochemical changes in sperm cells, including cholesterol efflux and tyrosine phosphorylation of sperm proteins.50 Hence, it is reasonable to believe that PPARγ participates in capacitation by glucose metabolism or other metabolic pathways, and increases the motility of capacitated spermatozoa.

Glucose metabolism is a critical pathway that can produce sufficient energy for the sustenance of life. Given the beneficial effects of PPARγ ligands in therapies aimed at lowering glucose levels in type 2 diabetes, a role for PPARγ in glucose metabolism has been explored.74,75 The effect of glucose on the fertilizing ability of spermatozoa appears to be mediated by the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP).76 Metabolism of G-6-P through the PPP yields much more nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide hydrogenase (NADPH) than glycolysis and TCA cycle, and NADPH acts as a hydrogen donor in many chemical reactions in vivo.77 G6PDH is a key rate-limiting enzyme in this metabolic pathway and has been shown to be functional in human spermatozoa.78 PPARγ is able to modulate in a dose-dependent way the activity of G6PDH in spermatozoa.50 Meanwhile, PPARγ has the potential to increase peripheral tissue sensitivity to insulin, thereby improving insulin resistance. Insulin resistance appears to negatively affect the sperm quantity and quality.79 Moreover, insulin is a known mediator and modulator of the HPG axis, contributing to the regulation of male reproductive potential and overall wellbeing.79,80 Its disruption of the HPG axis can render patients hypogonadal. It has been shown that hyperinsulinemia is associated with increased seminal insulin concentrations, which may negatively impact male reproductive function in obesity.80

CROSS-TALK BETWEEN PEROXISOME PROLIFERATOR-ACTIVATED RECEPTOR GAMMA AND SIGNALING TRANSDUCTION PATHWAYS

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and the PI3K signal transduction pathway

Once an insulin receptor substrate (IRS) combine with its catalytic subunits, the IRS catalyzes the phosphorylation of membrane phosphatidylinositol (PI). PI3K, which has been shown to be active in human spermatozoa,81 is important in a wide variety of cellular processes in which PI3K activation leads to production of 3’- phosphoinositide second messengers, such as PI- 3,4,5-trisphosphate, which activate a variety of downstream cell survival signals.82 Accumulation of PI 3,4,5-trisphosphate in the membrane recruits a number of signaling proteins containing pleckstrin homology domains, including AKT and PDK1.82,83 On recruitment, AKT becomes phosphorylated and activated by a series of enzymes, kinases and transcription factors downstream, and yields a variety of biological functions, including intracellular trafficking, organization of the cytoskeleton, cell growth and transformation, and prevention of apoptosis.84,85 Interestingly, AKT is able to stimulate the metabolism of glucose through activation of AS160, the substrate of AKT, and promotes transposition of GLUT4 and absorption of glucose into muscle cells. PPARγ activation has been reported to regulate components of the PI3K signaling cascade in various cell types,86 enhancing the sensitivity of insulin. Elevation of Glut4 and PPAR gene expression in parallel with glucose uptake has been confirmed by in vitro glucose uptake activity.87 There is evidence that increasing doses of PPARγ agonists increase Akt1/Akt2/Akt3 significantly, whereupon. AKT, the major downstream gene of PI3K signal transducer, is fully activated.50

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and the leptin signal transduction pathway

In addition to its role in metabolic control, leptin has pivotal roles in reproduction88 and neuroendocrine signaling.89,90 Various pieces of evidence have pointed to a direct role of leptin in the control of male reproduction.91,92,93,94 In particular, ob/ob male mice (lacking functional leptin) or db/db male mice (lacking functional leptin receptor) are infertile and fail to undergo normal sexual maturation.95 In human, leptin is expressed in the seminiferous tubules96,97 and in seminal plasma98,99 while the leptin receptor is found in the interstitium, primarily in the Leydig cells.97 Worthy of note, Camiña et al. first proposed that human leptin is present in seminal fluid, with at least two charge variants and no binding proteins, the most likely source being either the seminal vesicles or prostate.99 Hence, it is reasonable to speculate that leptin has a direct (paracrine, autocrine or both) effect on epithelial cells of the male accessory genital glands, and on the spermatozoa via sperm leptin receptors.100 OBR, a single membrane-spanning glycoprotein, belonging to the class I cytokine receptor superfamily, shares sequence homologies for interaction with Janus kinase (JAK) as well as STATs.101 Nonetheless, PPARγ, whose promoter region is rich in multiple Stat5 DNA binding consensus sequences, is downstream of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway,102 suggesting that expression of this gene is regulated by the JAK/STAT pathway.

Experimental studies have shown that leptin treatment results in a significant increase in cholesterol efflux from and protein tyrosine phosphorylation of pig spermatozoa, stimulates pig sperm acrosin activity,103 two events associated with capacitation.104,105,106 Compelling evidence suggests that leptin has a direct inhibitory effect on rosiglitazone-induced adipocyte differentiation and PPARγ expression, in which ERK1/2 MAPK and JAK/STAT1 signaling pathways are involved.107,108 Several studies have supported a relationship between increased leptin production and regulation of reproductive function. Indeed, leptin plays a critical role at every level of the HPG axis in males. Most obese male mice become insensitive to increased endogenous leptin production and develop functional leptin resistance.109,110 This deregulation of leptin signaling might result in abnormal endocrine and reproductive functions with altered leptin dynamics, and may contribute to male infertility in different ways, leading to hypogonadism.111 Therefore, PPARγ agonists may enhance the sensitivity of insulin, acting as a potential therapy for hypogonadism.

SUMMARY

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma may play a key role in linking lipid metabolism and reproduction in general. Energy from glucose and fat metabolism mediated by PPARγ signaling is required for sperm physiology, affecting male fertility. These recent experiments raise several questions. One question concerns PPARγ agonist activation of related metabolic pathways. Owing to the role of PPARγ in sperm capacitation, the use of its agonists may be considered a strategy in artificial insemination or other biotechnologies. Another question is whether the positive effects of PPARγ agonists are due to a direct effect on the testis or a positive effect on glucose homeostasis. Further experiments are needed to increase our knowledge of the way in which PPARγ signaling maintains sperm viability.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

LL drafted the manuscript. HX and JCC participated in the design of the study and helped draft the manuscript. CZ, YHZ, MMC and YQ helped draft the manuscript. MJ conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Douglas Strand at UT Southwestern Medical Center for his critical comments on the manuscript. The research project was supported by The National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, Grant No. 81372772, PI: Ming Jiang), the Scientific Research Foundation for Jiangsu Specially-Appointed Professor (Sujiaoshi (2012) 34, PI: Ming Jiang), Department of Education in Jiangsu Province, China and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD), China.

REFERENCES

- 1.Issemann I, Green S. Activation of a member of the steroid hormone receptor superfamily by peroxisome proliferators. Nature. 1990;347:645–50. doi: 10.1038/347645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sørensen HN, Treuter E, Gustafsson JA. Regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Vitam Horm. 1998;54:121–66. doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(08)60924-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ehrmann J, Jr, Vavrusová N, Collan Y, Kolár Z. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) in health and disease. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2002;146:11–4. doi: 10.5507/bp.2002.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robinson E, Grieve DJ. Significance of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in the cardiovascular system in health and disease. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;122:246–63. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vamecq J, Cherkaoui-Malki M, Andreoletti P, Latruffe N. The human peroxisome in health and disease: the story of an oddity becoming a vital organelle. Biochimie. 2014;98:4–15. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho HK, Kong HJ, Nam BH, Kim WJ, Noh JK, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2009;163:251–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oku H, Umino T. Molecular characterization of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) and their gene expression in the differentiating adipocytes of red sea bream Pagrus major. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;151:268–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abbott BD. Review of the expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors alpha (PPAR alpha), beta (PPAR beta), and gamma (PPAR gamma) in rodent and human development. Reprod Toxicol. 2009;27:246–57. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li S, Gul Y, Wang W, Qian X, Zhao Y. PPARã, an important gene related to lipid metabolism and immunity in Megalobrama amblycephala: cloning, characterization and transcription analysis by GeNorm. Gene. 2013;512:321–30. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsai ML, Chen HY, Tseng MC, Chang RC. Cloning of peroxisome proliferators activated receptors in the cobia (Rachycentron canadum) and their expression at different life-cycle stages under cage aquaculture. Gene. 2008;425:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Froment P, Gizard F, Defever D, Staels B, Dupont J, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in reproductive tissues: from gametogenesis to parturition. J Endocrinol. 2006;189:199–209. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moschos S, Chan JL, Mantzoros CS. Leptin and reproduction: a review. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:433–44. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)03010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cui Y, Miyoshi K, Claudio E, Siebenlist UK, Gonzalez FJ, et al. Loss of the peroxisome proliferation-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) does not affect mammary development and propensity for tumor formation but leads to reduced fertility. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:17830–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200186200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aquila S, Bonofiglio D, Gentile M, Middea E, Gabriele S, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) gamma is expressed by human spermatozoa: its potential role on the sperm physiology. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209:977–86. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aquila S, Middea E, Catalano S, Marsico S, Lanzino M, et al. Human sperm express a functional androgen receptor: effects on PI3K/AKT pathway. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:2594–605. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guido C, Perrotta I, Panza S, Middea E, Avena P, et al. Human sperm physiology: estrogen receptor alpha (ERa) and estrogen receptor beta (ERß) influence sperm metabolism and may be involved in the pathophysiology of varicocele-associated male infertility. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:3403–12. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aquila S, Gentile M, Middea E, Catalano S, Andò S. Autocrine regulation of insulin secretion in human ejaculated spermatozoa. Endocrinology. 2005;146:552–7. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aquila S, Gentile M, Middea E, Catalano S, Morelli C, et al. Leptin secretion by human ejaculated spermatozoa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:4753–61. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heaney AP, Fernando M, Melmed S. PPAR-gamma receptor ligands: novel therapy for pituitary adenomas. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1381–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI16575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiesner G, Morash BA, Ur E, Wilkinson M. Food restriction regulates adipose-specific cytokines in pituitary gland but not in hypothalamus. J Endocrinol. 2004;180:R1–6. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.180r001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mouihate A, Boissé L, Pittman QJ. A novel antipyretic action of 15-deoxy-Delta12,14-prostaglandin J2 in the rat brain. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1312–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3145-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giustina A, Barkan A, Casanueva FF, Cavagnini F, Frohman L, et al. Criteria for cure of acromegaly: a consensus statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:526–9. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.2.6363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharma S, Sharma PM, Mistry DS, Chang RJ, Olefsky JM, et al. PPARG regulates gonadotropin-releasing hormone signaling in LbetaT2 cells in vitro and pituitary gonadotroph function in vivo in mice. Biol Reprod. 2011;84:466–75. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.088005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang H, Li Q, Lin H, Yang Q, Wang H, et al. Role of PPARgamma and its gonadotrophic regulation in rat ovarian granulosa cells in vitro. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2007;28:289–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhattacharya N, Dufour JM, Vo MN, Okita J, Okita R, et al. Differential effects of phthalates on the testis and the liver. Biol Reprod. 2005;72:745–54. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.031583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Y, Ramdhan DH, Naito H, Yamagishi N, Ito Y, et al. Ammonium perfluorooctanoate may cause testosterone reduction by adversely affecting testis in relation to PPARa. Toxicol Lett. 2011;205:265–72. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corton JC, Lapinskas PJ. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: mediators of phthalate ester-induced effects in the male reproductive tract? Toxicol Sci. 2005;83:4–17. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mackay S. Gonadal development in mammals at the cellular and molecular levels. Int Rev Cytol. 2000;200:47–99. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(00)00002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krishnamoorthy G, Selvakumar K, Venkataraman P, Elumalai P, Arunakaran J. Lycopene supplementation prevents reactive oxygen species mediated apoptosis in Sertoli cells of adult albino rats exposed to polychlorinated biphenyls. Interdiscip Toxicol. 2013;6:83–92. doi: 10.2478/intox-2013-0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas K, Sung DY, Chen X, Thompson W, Chen YE, et al. Developmental patterns of PPAR and RXR gene expression during spermatogenesis. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2011;3:1209–20. doi: 10.2741/E324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.White-Cooper H, Bausek N. Evolution and spermatogenesis. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2010;365:1465–80. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Navarro VM, Tena-Sempere M. Neuroendocrine control by kisspeptins: role in metabolic regulation of fertility. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;8:40–53. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sale EM, Denton RM. Beta-adrenergic agents increase the phosphorylation of phosphofructokinase in isolated rat epididymal white adipose tissue. Biochem J. 1985;232:905–10. doi: 10.1042/bj2320905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Floryk D, Kurosaka S, Tanimoto R, Yang G, Goltsov A, et al. Castration-induced changes in mouse epididymal white adipose tissue. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;345:58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang QA, Tao C, Gupta RK, Scherer PE. Tracking adipogenesis during white adipose tissue development, expansion and regeneration. Nat Med. 2013;19:1338–44. doi: 10.1038/nm.3324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pichiah PB, Sankarganesh A, Kalaiselvi S, Indirani K, Kamalakkannan S, et al. Adriamycin induced spermatogenesis defect is due to the reduction in epididymal adipose tissue mass: a possible hypothesis. Med Hypotheses. 2012;78:218–20. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2011.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chu Y, Huddleston GG, Clancy AN, Harris RB, Bartness TJ. Epididymal fat is necessary for spermatogenesis, but not testosterone production or copulatory behavior. Endocrinology. 2010;151:5669–79. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grün F, Watanabe H, Zamanian Z, Maeda L, Arima K, et al. Endocrine-disrupting organotin compounds are potent inducers of adipogenesis in vertebrates. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:2141–55. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu Y, Qi C, Jain S, Rao MS, Reddy JK. Isolation and characterization of PBP, a protein that interacts with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25500–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Han K, Song H, Moon I, Augustin R, Moley K, et al. Utilization of DR1 as true RARE in regulating the Ssm, a novel retinoic acid-target gene in the mouse testis. J Endocrinol. 2007;192:539–51. doi: 10.1677/JOE-06-0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kapoor A, Shintani Y, Collino M, Osuchowski MF, Busch D, et al. Protective role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-ß/d in septic shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:1506–15. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201002-0240OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Kretser DM, Loveland KL, Meinhardt A, Simorangkir D, Wreford N. Spermatogenesis. Hum Reprod. 1998;13(Suppl 1):1–8. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.suppl_1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chu DS, Shakes DC. Spermatogenesis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;757:171–203. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-4015-4_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duplus E, Glorian M, Forest C. Fatty acid regulation of gene transcription. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:30749–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R000015200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lishko PV, Kirichok Y, Ren D, Navarro B, Chung JJ, et al. The control of male fertility by spermatozoan ion channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 2012;74:453–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-020911-153258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Breitbart H. Signaling pathways in sperm capacitation and acrosome reaction. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2003;49:321–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Visconti PE, Moore GD, Bailey JL, Leclerc P, Connors SA, et al. Capacitation of mouse spermatozoa. II. Protein tyrosine phosphorylation and capacitation are regulated by a cAMP-dependent pathway. Development. 1995;121:1139–50. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.4.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brener E, Rubinstein S, Cohen G, Shternall K, Rivlin J, et al. Remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton during mammalian sperm capacitation and acrosome reaction. Biol Reprod. 2003;68:837–45. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.009233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang L, Chen W, Zhao C, Huo R, Guo XJ, et al. The role of ezrin-associated protein network in human sperm capacitation. Asian J Androl. 2010;12:667–76. doi: 10.1038/aja.2010.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Santoro M, Guido C, De Amicis F, Sisci D, Vizza D, et al. Sperm metabolism in pigs: a role for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARã) J Exp Biol. 2013;216:1085–92. doi: 10.1242/jeb.079327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Skakkebaek NE, Jørgensen N, Main KM, Rajpert-De Meyts E, Leffers H, et al. Is human fecundity declining? Int J Androl. 2006;29:2–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2005.00573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Che Y, Cleland J. Infertility in Shanghai: prevalence, treatment seeking and impact. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;22:643–8. doi: 10.1080/0144361021000020457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hultman CM, Sandin S, Levine SZ, Lichtenstein P, Reichenberg A. Advancing paternal age and risk of autism: new evidence from a population-based study and a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16:1203–12. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cooper R, Hyppönen E, Berry D, Power C. Associations between parental and offspring adiposity up to midlife: the contribution of adult lifestyle factors in the 1958 British Birth Cohort Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:946–53. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Milne E, Greenop KR, Scott RJ, Bailey HD, Attia J, et al. Parental prenatal smoking and risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175:43–53. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Halliday J. Outcomes for offspring of men having ICSI for male factor infertility. Asian J Androl. 2012;14:116–20. doi: 10.1038/aja.2011.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Olsen J, Ramlau-Hansen CH. Dietary fats may impact semen quantity and quality. Asian J Androl. 2012;14:511–2. doi: 10.1038/aja.2012.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Safarinejad MR, Azma K, Kolahi AA. The effects of intensive, long-term treadmill running on reproductive hormones, hypothalamus-pituitary-testis axis, and semen quality: a randomized controlled study. J Endocrinol. 2009;200:259–71. doi: 10.1677/JOE-08-0477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Palmer NO, Bakos HW, Fullston T, Lane M. Impact of obesity on male fertility, sperm function and molecular composition. Spermatogenesis. 2012;2:253–63. doi: 10.4161/spmg.21362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lampiao F. Variation of semen parameters in healthy medical students due to exam stress. Malawi Med J. 2009;21:166–7. doi: 10.4314/mmj.v21i4.49635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gollenberg AL, Liu F, Brazil C, Drobnis EZ, Guzick D, et al. Semen quality in fertile men in relation to psychosocial stress. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:1104–11. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ghanayem BI, Bai R, Kissling GE, Travlos G, Hoffler U. Diet-induced obesity in male mice is associated with reduced fertility and potentiation of acrylamide-induced reproductive toxicity. Biol Reprod. 2010;82:96–104. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.078915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ng SF, Lin RC, Laybutt DR, Barres R, Owens JA, et al. Chronic high-fat diet in fathers programs ß-cell dysfunction in female rat offspring. Nature. 2010;467:963–6. doi: 10.1038/nature09491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Palmer NO, Bakos HW, Owens JA, Setchell BP, Lane M. Diet and exercise in an obese mouse fed a high-fat diet improve metabolic health and reverse perturbed sperm function. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;302:E768–80. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00401.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nandi A, Wang X, Accili D, Wolgemuth DJ. The effect of insulin signaling on female reproductive function independent of adiposity and hyperglycemia. Endocrinology. 2010;151:1863–71. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schoeller EL, Albanna G, Frolova AI, Moley KH. Insulin rescues impaired spermatogenesis via the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis in Akita diabetic mice and restores male fertility. Diabetes. 2012;61:1869–78. doi: 10.2337/db11-1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tena-Sempere M. Interaction between energy homeostasis and reproduction: central effects of leptin and ghrelin on the reproductive axis. Horm Metab Res. 2013;45:919–27. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1355399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tena-Sempere M, Pinilla L, González LC, Diéguez C, Casanueva FF, et al. Leptin inhibits testosterone secretion from adult rat testis in vitro. J Endocrinol. 1999;161:211–8. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1610211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Baldelli R, Dieguez C, Casanueva FF. The role of leptin in reproduction: experimental and clinical aspects. Ann Med. 2002;34:5–18. doi: 10.1080/078538902317338599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vélez LM, Abruzzese GA, Motta AB. The biology of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor system in the female reproductive tract. Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19:4641–6. doi: 10.2174/1381612811319250010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.He W, Barak Y, Hevener A, Olson P, Liao D, et al. Adipose-specific peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma knockout causes insulin resistance in fat and liver but not in muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15712–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2536828100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jiang M, Shappell SB, Hayward SW. Approaches to understanding the importance and clinical implications of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) signaling in prostate cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2004;91:513–27. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sugii S, Olson P, Sears DD, Saberi M, Atkins AR, et al. PPARgamma activation in adipocytes is sufficient for systemic insulin sensitization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:22504–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912487106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Krentz AJ, Friedmann PS. Type 2 diabetes, psoriasis and thiazolidinediones. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:362–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2005.00765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Savkur RS, Miller AR. Investigational PPAR-gamma agonists for the treatment of Type 2 diabetes. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2006;15:763–78. doi: 10.1517/13543784.15.7.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Miraglia E, Lussiana C, Viarisio D, Racca C, Cipriani A, et al. The pentose phosphate pathway plays an essential role in supporting human sperm capacitation. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:2437–40. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Peña FJ, Rodríguez Martínez H, Tapia JA, Ortega Ferrusola C, González Fernández L, et al. Mitochondria in mammalian sperm physiology and pathology: a review. Reprod Domest Anim. 2009;44:345–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2008.01211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Aquila S, Guido C, Middea E, Perrotta I, Bruno R, et al. Human male gamete endocrinology: 1alpha, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3) regulates different aspects of human sperm biology and metabolism. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2009;7:140. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-7-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Morrison CD, Brannigan RE. Metabolic syndrome and infertility in men. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2014 Oct 24; doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2014.10.006. pii: S1521-6934(14)00217-X. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2014.10.006. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Leisegang K, Bouic PJ, Menkveld R, Henkel RR. Obesity is associated with increased seminal insulin and leptin alongside reduced fertility parameters in a controlled male cohort. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2014;12:34. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-12-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Luconi M, Carloni V, Marra F, Ferruzzi P, Forti G, et al. Increased phosphorylation of AKAP by inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase enhances human sperm motility through tail recruitment of protein kinase A. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:1235–46. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cantley LC. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science. 2002;31(296):1655–7. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5573.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lawlor MA, Alessi DR. PKB/Akt: a key mediator of cell proliferation, survival and insulin responses? J Cell Sci. 2001;114:2903–10. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.16.2903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ballester J, Fernández-Novell JM, Rutllant J, García-Rocha M, Jesús Palomo M, et al. Evidence for a functional glycogen metabolism in mature mammalian spermatozoa. Mol Reprod Dev. 2000;56:207–19. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(200006)56:2<207::AID-MRD12>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vanhaesebroeck B, Leevers SJ, Panayotou G, Waterfield MD. Phosphoinositide 3-kinases: a conserved family of signal transducers. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:267–72. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01061-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bonofiglio D, Gabriele S, Aquila S, Catalano S, Gentile M, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha binds to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor response element and negatively interferes with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma signaling in breast cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6139–47. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Anandharajan R, Pathmanathan K, Shankernarayanan NP, Vishwakarma RA, Balakrishnan A. Upregulation of Glut-4 and PPAR gamma by an isoflavone from Pterocarpus marsupium on L6 myotubes: a possible mechanism of action. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;97:253–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Prolo P, Wong ML, Licinio J. Leptin. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1998;30:1285–90. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(98)00094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Auwerx J, Staels B. Leptin. Lancet. 1998;351:737–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)06348-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ahima RS, Flier JS. Leptin. Annu Rev Physiol. 2000;62:413–37. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.62.1.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tena-Sempere M, Barreiro ML. Leptin in male reproduction: the testis paradigm. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;188:9–13. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Caprio M, Fabbrini E, Isidori AM, Aversa A, Fabbri A. Leptin in reproduction. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2001;12:65–72. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(00)00352-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tena-Sempere M, Manna PR, Zhang FP, Pinilla L, González LC, et al. Molecular mechanisms of leptin action in adult rat testis: potential targets for leptin-induced inhibition of steroidogenesis and pattern of leptin receptor messenger ribonucleic acid expression. J Endocrinol. 2001;170:413–23. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1700413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.White JT, DeSanto CL, Gibbons C, Lardner CK, Panakos A, et al. Insulins, leptin and feeding in a population of Peromyscus leucopus (white-footed mouse) with variable fertility. Horm Behav. 2014;66:169–79. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mounzih K, Lu R, Chehab FF. Leptin treatment rescues the sterility of genetically obese ob/ob males. Endocrinology. 1997;138:1190–3. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.3.5024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Soyupek S, Armagan A, Serel TA, Hoscan MB, Perk H, et al. Leptin expression in the testicular tissue of fertile and infertile men. Arch Androl. 2005;51:239–46. doi: 10.1080/01485010590919666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ishikawa T, Fujioka H, Ishimura T, Takenaka A, Fujisawa M. Expression of leptin and leptin receptor in the testis of fertile and infertile patients. Andrologia. 2007;39:22–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2006.00754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Glander HJ, Lammert A, Paasch U, Glasow A, Kratzsch J. Leptin exists in tubuli seminiferi and in seminal plasma. Andrologia. 2002;34:227–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0272.2002.00501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Camiña JP, Lage M, Menendez C, Graña M, García-Devesa J, et al. Evidence of free leptin in human seminal plasma. Endocrine. 2002;17:169–74. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:17:3:169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sayed-Ahmed A, Abd-Elmaksoud A, Elnasharty M, El-Magd MA. In situ hybridization and immunohistochemical localization of leptin hormone and leptin receptor in the seminal vesicle and prostate gland of adult rat. Acta Histochem. 2012;114:185–91. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tartaglia LA. The leptin receptor. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:6093–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.10.6093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Davoodi-Semiromi A, Hassanzadeh A, Wasserfall CH, Droney A, Atkinson M. Tyrphostin AG490 agent modestly but significantly prevents onset of type 1 in NOD mouse; implication of immunologic and metabolic effects of a Jak-Stat pathway inhibitor. J Clin Immunol. 2012;32:1038–47. doi: 10.1007/s10875-012-9707-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Aquila S, Rago V, Guido C, Casaburi I, Zupo S, et al. Leptin and leptin receptor in pig spermatozoa: evidence of their involvement in sperm capacitation and survival. Reproduction. 2008;136:23–32. doi: 10.1530/REP-07-0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Visconti PE, Ning X, Fornés MW, Alvarez JG, Stein P, et al. Cholesterol efflux-mediated signal transduction in mammalian sperm: cholesterol release signals an increase in protein tyrosine phosphorylation during mouse sperm capacitation. Dev Biol. 1999;214:429–43. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Osheroff JE, Visconti PE, Valenzuela JP, Travis AJ, Alvarez J, et al. Regulation of human sperm capacitation by a cholesterol efflux-stimulated signal transduction pathway leading to protein kinase A-mediated up-regulation of protein tyrosine phosphorylation. Mol Hum Reprod. 1999;5:1017–26. doi: 10.1093/molehr/5.11.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Travis AJ, Kopf GS. The role of cholesterol efflux in regulating the fertilization potential of mammalian spermatozoa. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:731–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI16392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rhee SD, Sung YY, Jung WH, Cheon HG. Leptin inhibits rosiglitazone-induced adipogenesis in murine primary adipocytes. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008;294:61–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kim WK, Lee CY, Kang MS, Kim MH, Ryu YH, et al. Effects of leptin on lipid metabolism and gene expression of differentiation-associated growth factors and transcription factors during differentiation and maturation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Endocr J. 2008;55:827–37. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k08e-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tortoriello DV, McMinn JE, Chua SC. Increased expression of hypothalamic leptin receptor and adiponectin accompany resistance to dietary-induced obesity and infertility in female C57BL/6J mice. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:395–402. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tortoriello DV, McMinn J, Chua SC. Dietary-induced obesity and hypothalamic infertility in female DBA/2J mice. Endocrinology. 2004;145:1238–47. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Landry D, Cloutier F, Martin LJ. Implications of leptin in neuroendocrine regulation of male reproduction. Reprod Biol. 2013;13:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.repbio.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]