Whole-genome resequencing of Chlamydomonas reveals enormous intraspecific diversity and a reservoir of naturally occurring variation, including candidate loss-of-function alleles.

Abstract

We performed whole-genome resequencing of 12 field isolates and eight commonly studied laboratory strains of the model organism Chlamydomonas reinhardtii to characterize genomic diversity and provide a resource for studies of natural variation. Our data support previous observations that Chlamydomonas is among the most diverse eukaryotic species. Nucleotide diversity is ∼3% and is geographically structured in North America with some evidence of admixture among sampling locales. Examination of predicted loss-of-function mutations in field isolates indicates conservation of genes associated with core cellular functions, while genes in large gene families and poorly characterized genes show a greater incidence of major effect mutations. De novo assembly of unmapped reads recovered genes in the field isolates that are absent from the CC-503 assembly. The laboratory reference strains show a genomic pattern of polymorphism consistent with their origin as the recombinant progeny of a diploid zygospore. Large duplications or amplifications are a prominent feature of laboratory strains and appear to have originated under laboratory culture. Extensive natural variation offers a new source of genetic diversity for studies of Chlamydomonas, including naturally occurring alleles that may prove useful in studies of gene function and the dissection of quantitative genetic traits.

INTRODUCTION

Green algae are a large group of eukaryotic organisms comprising ∼8000 photosynthetic species that include the direct ancestors of land plants (Norton et al., 1996; Parfrey et al., 2006). Unicellular algae have served as models for many fundamental cellular processes, including flagellar assembly, motility, DNA methylation, photosynthesis, chloroplast biogenesis, metabolism, and sex determination (Harris, 2001). They have recently attracted attention for their utility in industrial applications including biofuel production (Brennan and Owende, 2010). The genomes of at least five algal species have been sequenced (Kim et al., 2014), and comparative analysis has yielded important insights into the biology and metabolic diversity of algae (Hildebrand et al., 2013) and the evolution of multicellularity (Prochnik et al., 2010).

Among green algae, the unicellular flagellate species Chlamydomonas reinhardtii has served as a widely studied model system in cellular and molecular biology (Kindle, 1990; Hippler et al., 1998; Merchant et al., 2007; Neupert et al., 2009). Chlamydomonas is a heterothallic species that persists as a haploid that is one of two distinct mating types (mt+ or mt−) during the vegetative stage of its life cycle. Reproductively compatible strains have been isolated from freshwater and moist soils in North America and Japan (Nakada et al., 2014) and can switch between photoautotrophic and mixotrophic strategies when provided with a suitable carbon source. In addition, practical characteristics such as the ease with which it can be cultured, the ability to conduct conventional genetic crosses, and the relative simplicity of genetic manipulation make Chlamydomonas a preferred alga for experimental studies (Graham, 1997; Harris, 2008). The completion of the ∼112-Mb genome sequence in 2007 (Merchant et al., 2007; Chlamydomonas JGI genome sequence version 4) has enabled new advances in algal genomics (Umen and Olson, 2012), and high-throughput genomic applications now complement traditional genetic approaches in studies of Chlamydomonas (Zhang et al., 2014; Jinkerson and Jonikas, 2015).

Patterns of genomic diversity provide insights into the evolutionary history and dynamics of species, and analysis of natural variation allows comparison of genome evolution between taxa. Among land plants, assessment of whole-genome intraspecific diversity in Arabidopsis thaliana (Cao et al., 2011), the Asian rice Oryza sativa (Xu et al., 2012), the African rice Oryza glaberrima (Wang et al., 2014), and the soybean Glycine max (Li et al., 2013) have provided valuable insight into evolutionary processes, while providing sources of variation for crop improvement (Xu et al., 2006). At present, we know very little about genomic diversity in the photosynthetic algae particularly at the level of intraspecific variation. By examining variation in field isolates of Chlamydomonas, we characterized genomic diversity in a model algae species and provide a resource for comparative analysis across a wider range of photosynthetic species, while identifying classes of genes that may harbor functionally important variation.

The first laboratory strain of Chlamydomonas was isolated in 1945 by Gilbert Smith in soil samples from Amherst, Massachusetts (Harris, 2008). Sequence data are consistent with this isolate being a single zygospore whose progeny have been exchanged among laboratories worldwide and are now represented by at least 10 widely used laboratory strains (Harris, 2001, 2008). The genealogy of these strains is fairly well known (Pröschold et al., 2005; Harris, 2008), providing a historical framework for relationships among them. Studies of natural variation in Chlamydomonas further benefit from the isolation and maintenance of field isolates (∼30 strains in total) that can be mated and will then produce stable progeny in the laboratory (Hoshaw and Ettl, 1966; Gross et al., 1988; Spanier et al., 1992; Sack et al., 1994; Harris, 2008). With the possible exception of the strain S1 D2 (i.e., CC-2290) (Gross et al., 1988), these environmental isolates are relatively poorly understood. Studies of genetic variation have found them to be highly polymorphic (Gross et al., 1988; Vysotskaia et al., 2001; Smith and Lee, 2008) with levels of nucleotide diversity ranking among the highest of known eukaryotes (Leffler et al., 2012). Genome diversity in Chlamydomonas also includes transposable element (TE) content variation among strains with one major transposon family, the Gulliver elements, present in all reference laboratory strains, but missing from the field isolate S1 D2 (Gross et al., 1988).

At present, there is little information on phenotypic variation among field strains (Hoshaw and Ettl, 1966; Gross et al., 1988), but important indicators such as differences in triacylglycerol accumulation among wild-type strains subjected to stress (Siaut et al., 2011) suggest that Chlamydomonas may harbor intraspecific diversity for important metabolic traits. Although little is known about trait variation at the cellular and molecular level, field isolates of Chlamydomonas offer a potentially large reservoir of functional variation from which recombinant genotypes can be generated for genetic mapping, functional studies, and evolutionary competition and selection experiments.

In this study, we present deep whole-genome resequencing data for 12 field isolates and eight laboratory reference (i.e., wild type) strains of Chlamydomonas. The field strains were chosen to represent all major geographic locales where Chlamydomonas strains had been obtained and deposited in the Chlamydomonas Resource Center (http://chlamycollection.org). The laboratory strains include many of the most widely studied experimental strains of Chlamydomonas. We report unusually high levels of polymorphism in strains isolated from the field, including more than six million single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in ∼112 Mb of assembled genome sequence (Merchant et al., 2007), and characterize major classes of structural variation including gene presence/absence variants (PAVs), copy number variants, and transposable element insertion polymorphisms. We describe the genomic pattern of polymorphism, characterize how it is structured geographically, and identify candidate loss-of-function (LOF) mutations, as these represent a potentially important source of phenotypic variation in field isolates of Chlamydomonas. In addition to the environmental isolates, we report considerable diversity within the reference laboratory strains, which likely traces to an original diploid zygospore from which laboratory strains are derived (Harris, 2008). Our analysis reveals important insights into the diversity of field isolates and laboratory reference strains, and it provides additional rationale for incorporating field isolates into experimental programs.

RESULTS

High Levels of Nucleotide Diversity in Chlamydomonas

We sequenced the genomes of the 12 field isolates and eight reference laboratory strains of Chlamydomonas to an aligned sequencing depth of ∼50X to 90X using paired end (2 × 51-bp) Illumina sequencing (Table 1). This strategy achieved a coverage breadth of 92 to 97% of the reference genome sequence in the field isolates and >99% in the laboratory reference strains. From the sequence alignments to the reference CC-503 cw92 mt+ strain (Merchant et al., 2007), we generated a filtered (see Methods) SNP data set that consisted of 6,424,876 biallelic SNPs in the field isolates. Together with predicted insertion/deletion mutations, gene content polymorphisms, TE insertion polymorphisms (Supplemental Data Set 1), and other classes of structural variants (Supplemental Data Set 2), these data represent many of the most common sequence polymorphisms in North American populations of Chlamydomonas and provide a source of naturally occurring genomic variants for experimental studies of this species (http://chlamy.abudhabi.nyu.edu).

Table 1. Summary of Resequencing Results for 20 Strains.

| Sample | Common Name | Type | Origin | Mapped Reads | Alignment Depth | Coverage Breadth | SNPsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC-2342 | Jarvik #6 | Field | Pittsburgh, PA | 147,205,747 | 67.44X | 0.93 | 2,140,208 |

| CC-4414 | DN2 | Field | Breckenridge, CO | 192,857,472 | 88.36X | 1.00 | 4,544b |

| CC-2290 | S1 D2 | Field | Minnesota | 109,731,811 | 50.27X | 0.93 | 2,213,037 |

| CC-2343 | Jarvik #224 | Field | Melbourne, FL | 113,970,105 | 52.21X | 0.92 | 2,351,729 |

| CC-2938 | – | Field | Quebec, Canada | 131,376,808 | 60.19X | 0.96 | 1,198,019 |

| CC-2935 | – | Field | Quebec, Canada | 110,280,091 | 50.52X | 0.95 | 1,538,010 |

| CC-2936 | – | Field | Quebec, Canada | 139,600,868 | 63.96X | 0.96 | 1,256,521 |

| CC-1373 | SAG 54.72 | Field | South Deerfield, MA | 158,057,156 | 72.41X | 0.97 | 1,184,917 |

| CC-2344 | Jarvik #356 | Field | Ralston, PA | 142,646,994 | 65.35X | 0.95 | 2,111,791 |

| CC-2931 | – | Field | Durham, NC | 132,165,181 | 60.55X | 0.94 | 2,224,262 |

| CC-2937 | – | Field | Quebec, Canada | 164,201,124 | 75.23X | 0.96 | 1,587,642 |

| CC-1952 | S1 C5 | Field | Minnesota | 140,337,443 | 64.29X | 0.94 | 2,254,451 |

| CC-503 | cw92 | Laboratory | – | 189,031,885 | 86.60X | 0.99 | 0c |

| CC-1010 | UTEX 90 | Laboratory | – | 196,963,413 | 90.24X | 0.99 | 61,737 |

| CC-1009 | UTEX 89 | Laboratory | – | 147,691,768 | 67.66X | 0.99 | 287,350 |

| CC-408 | C9 | Laboratory | – | 155,899,559 | 71.42X | 0.99 | 291,117 |

| CC-125 | 137c | Laboratory | – | 147,713,233 | 67.67X | 0.99 | 280 |

| CC-124 | 137c | Laboratory | – | 141,153,497 | 64.67X | 1.00 | 68,481 |

| CC-407 | C8 | Laboratory | – | 191,972,353 | 87.95X | 1.00 | 61,458 |

| CC-1690 | gr 21 | Laboratory | – | 173,866,820 | 79.65X | 1.00 | 61,477 |

SNPs with respect to CC-503.

CC-4414 appears to be a close relative of laboratory strains.

SNPs polymorphic in CC-503 were filtered from the final set.

Nucleotide diversity (π) (Nei, 1987) estimated in nonoverlapping 5-kb window ranges between 0.0005 and 0.0650 per site in field isolates of Chlamydomonas (Figure 1; Supplemental Figure 1). A mean π of 0.0283 ± 0.0073 per site indicates that two homologous sequences drawn at random from the field strains will on average differ at ∼3% of sites. Individual field isolates are diverged from the reference strain CC-503 by more than 2 million SNPs in our filtered data set (Table 1) with the most commonly studied isolate, CC-2290 (S1 D2), differing from CC-503 at 2,213,037 of 111,320,301 sites (∼19.9 SNPs/kb) in the reference assembly. Approximately 35% of SNPs (2,289,752 SNPs of 6,424,876) are restricted to individual strains, with between ∼1.6% (105,000 SNPs in strain CC-2936) and 7.1% (455,000 SNPs in CC-2343) of SNPs found as private alleles in any one isolate.

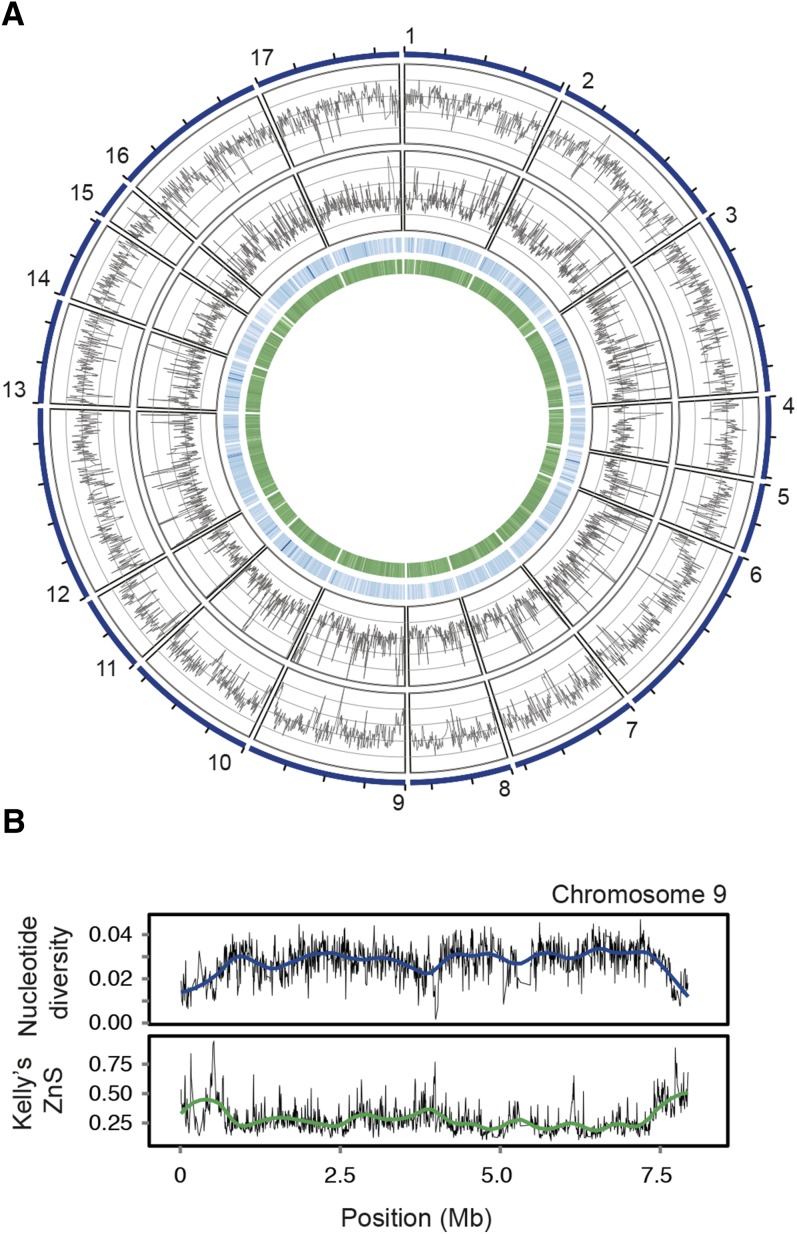

Figure 1.

Genome-Wide Pattern of Polymorphism in Field Isolates of Chlamydomonas.

(A) Genome-wide pattern of polymorphism in field isolates. Circos diagram illustrating (from outermost track to innermost track) nucleotide diversity (π; Nei, 1987), Kelly’s ZnS (i.e., mean linkage disequilibrium; Kelly, 1997), gene density, and GC content on the 17 chromosomes.

(B) Pattern of polymorphism on chromosome 9. Nucleotide diversity (upper panel) and Kelly’s ZnS (lower panel) on chromosome 9 estimated in nonoverlapping windows of 5 kb. Trend lines were fit to the raw data using Loess regression.

The genetic relationships among field strains suggest that genetic variation in Chlamydomonas populations is partitioned among geographic regions (i.e., geographically structured). In a principal component analysis (PCA), southeastern US strains (North Carolina, Florida, and Pennsylvania) and northeastern US/Canadian strains (Massachusetts and Quebec) form separate clusters that are also distinct from Minnesota (CC-2290 and CC-1952, designated as “West” in the PCA analysis) and the laboratory reference strains (Figure 2A). These relationships are also apparent in a neighbor-joining tree based on genome-wide SNP data in which the longest branches correspond to these same geographic groups of strains (Figure 2B), although it is less clear if CC-2290/CC-1952 form a distinct group. Both of the above analyses found the field isolate CC-4414 to be a close relative of the reference laboratory strains and identical-by-descent with CC-503 and CC-125 over most of the genome. This is unexpected and could reflect cross-contamination of strains; however, a segment at the end of the long arm of chromosome 16 is divergent from the other reference laboratory strains (data not shown) and indicates that CC-4414 is distinct from all other strains in our analysis.

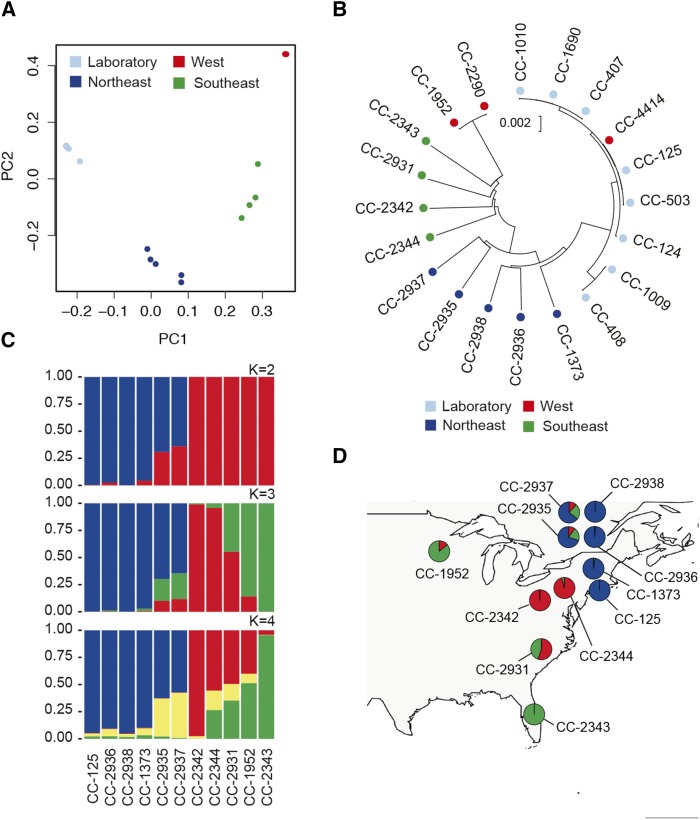

Figure 2.

Population Structure in Chlamydomonas.

(A) PCA of genotypes shows geographic clustering of strains. Sample CC-4414 (red) is hidden behind the cluster of laboratory strains (light blue).

(B) Neighbor-joining tree based on Jukes-Cantor corrected distances (Jukes and Cantor, 1969) for 20 strains. Samples are color-coded based on geographic groupings in (A).

(C) STRUCTURE (Pritchard et al., 2000) analysis based on 10 field isolates and a representative laboratory strain (CC-125). Results show admixture between three (K = 3) ancestral populations.

(D) Admixture proportions in each strain by sampling location. Admixture proportions from STRUCTURE (K = 3) in (C) suggest Chlamydomonas populations are subdivided geographically. Pie charts are placed at the approximate locations where the strains were isolated (Table 1).

Application of the clustering algorithm STRUCTURE (Pritchard et al., 2000) yielded results that are largely congruent with the PCA and neighbor-joining analysis. Population clustering of 10 field isolates (excluding CC-4414 and CC-2290) and one reference laboratory strain, CC-125 (137c), revealed three clusters (i.e., K= 3; Figure 2C; Supplemental Table 1 and Supplemental Methods) with CC-1373, CC-2936, CC-2938, and CC-125 in one cluster, CC-2343 and CC-1952 in a second, and strains CC-2342 and CC-2344 in a third. The remaining strains appear as admixed between these clusters with varying proportions of their genomes derived from two or more ancestral populations (Figure 2C). The geographic proximity of strains in the same cluster [e.g., CC-2342/CC-2344 and CC-1373/CC-125(137c)] supports the existence of geographically structured populations. Collectively, these observations suggest that Chlamydomonas is structured at a regional scale and likely forms three populations in North America. However, the co-occurrence of admixed strains (i.e., CC-2937 and CC-2935), which appear to be descendants of hybridization between genetically distinct individuals, and unadmixed strains (i.e., CC-2938 and CC-2936) in Quebec may suggest a more complex history of gene flow among sampling locations.

The genomic distribution of nucleotide polymorphism in the field isolates includes a significant reduction in diversity and elevated linkage disequilibrium (LD) at the ends of the chromosome arms. This is apparent on both short (Wilcoxon rank sum test, P < 2.2 × 10−16) and long arms (P = 1.0 × 10−10) and coincides with increased LD in these regions (Pshort < 2.2 × 10−16 and Plong = 1.23 × 10−8) measured as the mean r2 (i.e., Kelly’s ZnS) (Figure 1A). The rate of linkage LD decay is moderate, with associations between SNPs in the field strains decaying to near baseline levels within ∼20 kb (Supplemental Figure 2). This rate is nonuniform across chromosomes as chromosomes 2 and 9 have long-range associations that slow the rate of decay (Supplemental Figure 2; Jang and Ehrenreich, 2012). Increased LD and decreased π is most pronounced at the ends of chromosomes 9 and 10 (Figure 1B; Supplemental Figure 1) but is also apparent on other chromosomes (Figure 1A; Supplemental Figure 1). Reduction of π and increased LD at the ends of chromosomes is qualitatively similar to the reductions in polymorphism observed in Drosophila melanogaster species in regions of suppressed recombination and may be attributed to natural selection (e.g., genetic hitchhiking or background selection) or lower mutation rates at the tips of the chromosome arms (Begun et al., 2007).

Protein Coding Sequence Variation

Chlamydomonas coding regions are highly polymorphic in the field isolates, with ∼1.65 million SNPs found in ∼38.5 Mb of coding sequence genome-wide. Coding region SNPs consist of 609,011 nonsynonymous (9.5% of all SNPs), 1,048,396 synonymous (16.3%), and 1,202,170 intronic SNPs (18.7%). The high diversity introduces dense clusters of SNPs in protein coding regions and single codons frequently segregate two or three SNPs in the same codon. Approximately13.8% (266,252 SNPs) of coding sequence SNPs are located in such multi-SNP codons and were not classified as either nonsynonymous or synonymous as this requires knowledge of the order of mutational events (Nei and Gojobori, 1986).

Estimating nucleotide diversity at nonsynonymous (πN) and synonymous (πS) sites in genes with high levels of diversity requires a method that accounts for multi-SNP codons. Application of an evolutionary pathways approach (Nei and Gojobori, 1986; Korber, 2000) yielded estimates of πN and πS in the field isolates of 0.00690 ± 0.00005 and 0.0317 ± 0.0001, respectively. Using the πN/πS ratio as a measure of selective constraint on individual genes and the median πN/πS as a measure of constraint in classes of genes (Supplemental Data Set 3), we found genes without functional annotations (0.41 ± 0.006, mean ± se; see Methods) are less constrained than genes with an annotation (0.16 ± 0.002, Wilcoxon rank sum test, P < 2.2 × 10−16), suggesting that poorly characterized genes are less conserved. Among functional categories, genes functioning in photosynthesis, light perception (i.e., antennae proteins), vesicular transport, and protein translation, including ribosomal proteins, are broadly conserved with a large percentage of genes in these pathways being invariant at the amino acid level (Supplemental Data Set 4). Another class of conserved proteins includes members of a cytosolic sensing pathway (KEGG pathway: ko04623), which in higher eukaryotes function as PAMP recognition loci, a group of pattern recognition loci that detect conserved structures in microbial or viral pathogens.

Candidate LOF Alleles in Field Isolates of Chlamydomonas

LOF mutations in protein-coding genes are among the most common sources of adaptive variation (Hottes et al., 2013; Lind et al., 2015) and an obvious set of candidates for studies of phenotypic variation. To characterize the incidence of such major effect mutations in Chlamydomonas, we identified polymorphisms that are predicted to impact gene function, including nonsense mutations, splice donor/acceptor site mutations, and gene deletion or partial deletion variants.

Of the 17,535 protein-coding genes in the analysis, 714 (4.1%) are truncated by a premature stop, 1221 (7%) have SNPs in splice donor or acceptor sites, and 996 (5.7%) are either deleted or partially deleted in the field isolates relative to the reference strain CC-503 (Table 2; Supplemental Data Sets 5 and 6) based on a coverage breadth criterion (see Methods; Supplemental Data Set 7). In total, 1325 (7.5%) genes harbor either a predicted “damaging” nonsense mutation (i.e., a premature stop codon that truncates the protein by at least 25%; see below) or a gene deletion/partial deletion in at least one field isolate. In addition to these classes of major effect alleles, PAVs present in nonreference strains, but absent from CC-503, were discovered by de novo assembly of unmapped reads (see below). Together with other coding region mutations including TE insertions (Supplemental Data Set 1), these polymorphisms represent the best candidates for mutations that alter gene function in naturally occurring alleles of Chlamydomonas.

Table 2. Genes Affected by Candidate Major Effect Mutations in Chlamydomonas.

| Mutation Type | Field Isolates | Laboratory Strains |

|---|---|---|

| Deletions | 447 (2.5%) | 44 (0.3%) |

| Partial deletions | 549 (3.1%) | 61 (0.3%) |

| Nonsense (damaging)a | 394 (2.2%) | 24 (0.1%) |

| Nonsense (all) | 714 (4.1%) | 41 (0.2%) |

| Splice site | 1221 (7%) | 68 (0.4%) |

Percentages indicate the proportion of genes affected by each mutation type in at least one strain in 17,535 genes.

Nonsense mutations that prematurely truncate the protein by >25%.

Evaluation of the above mutation classes suggest that some may be poor indicators of LOF in Chlamydomonas and many candidate mutations may not alter protein function despite their predicted effect. For example, proteins encoded by 202 of the 714 (28%) genes with premature stop codons in the field isolates are truncated by 5% or less due to these mutations being located at the extreme C-terminal end of the protein (Figure 3A). Such nonsense polymorphisms at the extreme end of proteins may be tolerated either because protein function is maintained owing to minor length variation or because nonsense-mediated decay is inoperative in such cases. Predictions of the functional impacts of mutations are also sensitive to the gene model annotations used. Despite the high quality gene model annotations available for Chlamydomonas (Blaby et al., 2014), technical errors in structural annotations or usage of nonreference transcripts by other strains can lead to false predictions (Gan et al., 2011).

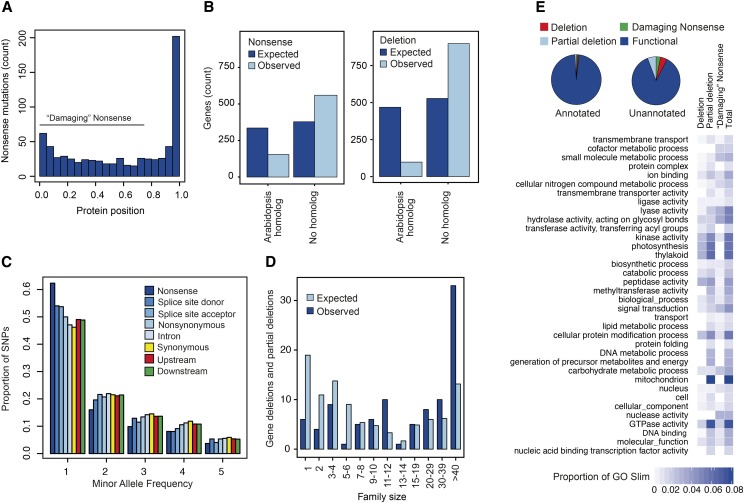

Figure 3.

Summary of Predicted Major Effect Mutations in Field Isolates of Chlamydomonas.

(A) Positions of predicted nonsense SNPs within proteins. The x axis values of 0.0 are at the N terminus and 1.0 at the C terminus. Positions of nonsense SNPs were rescaled based on the length of the protein as 1 – (amino acid position of the premature stop/protein length).

(B) Counts of genes with nonsense mutations (left) or deletions in classes of genes with and without a homolog in Arabidopsis. Nonsense mutation counts include only “damaging” mutations and deletions include partial deletions as defined in the text. Data are presented for observed and expected counts, where the expected is based on the expectation of homogeneity of counts between classes of genes with and without Arabidopsis homologs.

(C) Minor allele site frequency spectra for different mutational classes in the field isolates. Upstream and downstream classes represent intergenic SNPs within 500 bp of an annotated gene model.

(D) Gene family size and gene deletion polymorphisms in Chlamydomonas field isolates. Observed versus expected counts of gene deletions by gene family size, where expected counts are calculated as in (B). Only genes with a homolog in Arabidopsis are shown.

(E) Proportion of genes with major effect mutations based on their functional annotation status. The heat map illustrates the proportion of genes with a major effect mutation in the indicated GO Slim classes. GO Slims are only listed if more than 1% of the genes in the class have a predicted deletion, partial deletion, or “damaging” nonsense mutation that causes premature truncation by at least 25%.

Evaluation of the incidence of the predicted major effect mutations in essential versus nonessential genes provides a means of evaluating whether the candidate mutations we predict as a class are in fact detrimental to gene function. LOF mutations in essential genes are lethal in haploid organisms like Chlamydomonas, and false positives should therefore be homogeneously distributed between the two classes. Without a published list of essential genes for Chlamydomonas, we considered ancient homologs shared by algae and land plants to be a set of genes likely enriched for genes essential to cellular function and should therefore be depleted of LOF variants relative to other classes of genes (Chen et al., 2012; MacArthur et al., 2012). Of the 8243 Chlamydomonas genes with homologs in Arabidopsis, we find that gene deletions are significantly depleted in this set relative to genes without a homolog in Arabidopsis (Figure 3B, Table 3; P < 6.20 × 10−52). This pattern is also apparent for partial deletions (Figure 3B; P < 4.18 × 10−72) and nonsense mutations that truncate the protein by more than 25% (i.e., “damaging” nonsense mutations; Figure 3B) (P < 1.03 × 10−32). By contrast, splice site-altering mutations are only weakly depleted in the set of phylogenetically conserved genes (Table 3).

Table 3. Distribution of Candidate Loss-of-Function Alleles in Genes with and without Homologs in Arabidopsis.

| Mutation Type | Ancient Homolog |

No Ancient Homolog |

χ2 | Pa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Expected | Observed | Expected | |||

| Deletions | 50 | 210 | 397 | 237 | 229.9 | 6.2 × 10−52 |

| Partial deletions | 48 | 258 | 501 | 291 | 322.5 | 4.2 × 10−72 |

| All deletions | 98 | 468 | 898 | 528 | 551.8 | 5.1 × 10−122 |

| Nonsense (damaging)b | 67 | 185 | 327 | 209 | 141.9 | 1.0 × 10−32 |

| Nonsense (all) | 154 | 336 | 560 | 378 | 186.2 | 2.1 × 10−42 |

| Splice site | 530 | 574 | 691 | 647 | 6.4 | 1 × 10−2 |

χ2 test with 1 df.

Nonsense mutations that prematurely truncate the protein by >25%.

On average, nonsense mutations in our analysis are found at lower frequency than other classes of polymorphism in the field isolates (Figure 3C), which is consistent with purifying selection acting on mutations that prematurely truncate the protein. Although both splice donor and acceptor mutations are found at lower frequency than other classes of SNPs (Figure 3C), the frequency with which these mutations occur in ancient genes shared with Arabidopsis suggest they may be poor indicators of LOF. These observations suggest that deletions and nonsense mutations in Chlamydomonas are enriched for mutations that alter function and decrease fitness, while splice-site altering mutations are less likely candidates. For this reason, we limit our analysis below to deletions and nonsense mutation classes.

LOF Mutations in Gene Families

Functional redundancy in gene families is the primary compensating mechanism for null mutations in yeast (Gu et al., 2003) and could account for the major effect mutations in phylogenetically conserved genes. To evaluate if this mechanism contributes to the tolerance of LOF alleles in Chlamydomonas, we characterized how candidate LOF variants are distributed among gene families of different sizes. Considering phylogenetically conserved genes with a homolog in Arabidopsis, we found single-copy genes to infrequently harbor gene deletion polymorphisms. Six of 1595 (0.4%) single-copy genes are segregating for either a gene deletion or partial deletions, compared with 92 of 6647 (1.3%) genes in multigene families (χ2 = 10.0916, df = 1, P = 0.0015) (Figure 3D). “Damaging” nonsense mutations are also underrepresented in the singleton set with six SNPs in singletons and 61 SNPs in multigene family proteins (χ2 = 4.64, df = 1, P = 0.031). This effect of gene family size on gene deletions was not apparent when all gene families were considered or when considering genes without ancient homologs in Arabidopsis. Thus, although functional redundancy in the form of gene duplication appears to be an important mechanism in compensating for nonfunctional alleles, this buffering effect may be limited to core functions encoded by ancient gene families. The Chlamydomonas genome harbors more single-copy genes and smaller gene families than land plants (Gu et al., 2003; Merchant et al., 2007; Prochnik et al., 2010) and may thus have reduced potential for redundancy and limited buffering capacity against deleterious mutations, but our results suggest that functional redundancy is an important factor contributing to the segregation of null alleles.

Genes without homologs in land plants or other green algae represent an interesting class of genes that may confer Chlamydomonas-specific functions. We found candidate LOF mutations to be overrepresented in this class of 2634 genes relative to the remainder of the genome. This excess was apparent for both gene deletions/partial deletions (χ2 = 506.2, df = 1, P = 4.18e-112) and genes with damaging stop codons (χ2 = 35.57, df = 1, P = 2.466e-09). The overrepresentation of gene deletions/partial deletions in Chlamydomonas-specific genes was apparent for genes with (χ2 = 69.43, df = 1, P = 7.906e-17) and without (χ2 = 135.82, df = 1, P = 2.186e-31) a functional annotation in our database, although for genes with a damaging premature stop codon the pattern was limited to genes with an annotation (χ2 = 39.12, df = 1, P = 3.994e-10). The greater incidence of major effect mutations in Chlamydomonas-specific suggests that genes in this class are less likely to be essential compared with core genes shared with other organisms.

LOF Mutations by Functional Category

Characterization of candidate major effect mutations by functional category may yield insight into classes of genes that are essential in Chlamydomonas. Genes with KEGG pathway annotations (1903 in our analysis) show limited numbers of major effect mutations with three gene deletions (0.16%), five partial deletions (0.26%), and nine genes (0.47%) affected by damaging nonsense mutations (Kanehisa and Goto, 2000). A similarly small percentage of genes (2.8%, 182 of 6525) with a Gene Ontology (GO) annotation, have candidate major effect mutations. Among GO classes, signaling-related proteins such as kinases (Fisher’s exact test, false discovery rate-corrected Q < 0.01) and peptidases (Q < 0.05) under the molecular function ontology terms are significantly enriched for gene deletions. Gene deletions are also significantly enriched under the biological process ontology term cellular protein modification (Q < 0.01). GO slim terms for kinase activity, photosynthesis, thylakoid, and mitochondrion ranking are the categories most frequently impacted with candidate LOF mutations (Figure 3E; Supplemental Data Set 8). Functional classes defined by shared domain content are also enriched for gene deletions or partial deletions. For example, genes belonging to the protein kinases, proteases, a putative carbohydrate recognition (WSC) family, the PIF1-like helicases, and PHD finger proteins (involved in chromatin remodeling) are among those overrepresented for these classes of mutation (Table 4).

Table 4. Gene Families Enriched for Gene Deletions or Partial Deletions in Field Isolates of Chlamydomonas.

| Description | PFAM | n | Deletion |

No Deletion |

P | Q | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not in Family | In Family | Not in Family | In Family | |||||

| PIF1-like helicase | PF05970 | 11 | 146 | 8 | 8883 | 3 | 9.3 × 10−13 | 2.8 × 10−9 |

| PHD finger | PF00628 | 26 | 144 | 10 | 8870 | 16 | 6.4 × 10−12 | 9.7 × 10−9 |

| Protein kinase | PF00069 | 535 | 124 | 30 | 8381 | 505 | 5.1 × 10−9 | 5.1 × 10−6 |

| WSC | PF01822 | 21 | 147 | 7 | 8872 | 14 | 3.5 × 10−8 | 2.6 × 10−5 |

| Dama | PF05869 | 6 | 150 | 4 | 8884 | 2 | 1.2 × 10−6 | 0.0007 |

| Cysteine protease | PF00112 | 22 | 149 | 5 | 8869 | 17 | 2.8 × 10−5 | 0.0140 |

| Ulp1 protease | PF02902 | 6 | 151 | 3 | 8883 | 3 | 9.3 × 10−5 | 0.0358 |

| OB NTP bindb | PF07717 | 15 | 150 | 4 | 8875 | 11 | 9.5 × 10−5 | 0.0358 |

Two-tailed Fisher’s exact tests were conducted with the gene universe restricted to genes with an annotated PFAM domain. PFAM domain families that were significant after false discovery rate correction (Q < 0.05) are listed.

Dam, DNA N-6-adenine-methyltransferase.

Oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide binding (OB) fold.

Classes of genes of special interest in studies of Chlamydomonas include metabolic enzymes, members of the GreenCut2 (i.e., a class of proteins found only in photosynthetic organisms; Karpowicz et al., 2011), flagellar proteins (Pazour et al., 2005), and transcription factors (Zhang et al., 2011). Of the 1335 genes annotated with an Enzyme Commission number, 10 (0.7%) have either a deletion or premature stop codon predicted to truncate the protein by at least 25% (Supplemental Table 2). Proteins of the GreenCut2 (537 in our data set; see Methods) are similarly intolerant of major effect mutations (1 gene deletion, 2 partial gene deletions, 2 genes with “damaging” nonsense; Karpowicz et al., 2011), as are 350 flagellar proteins (0 gene deletions, 2 partial gene deletions, and 0 genes with “damaging” nonsense; Pazour et al., 2005) and 206 transcription factors (2 gene deletions, 1 partial gene deletion, and 4 genes with “damaging” nonsense; Zhang et al., 2011).

Unique Genes in Nonreference Strains of Chlamydomonas

An important class of PAV includes genes that are missing from the reference assembly and are therefore unknown. To identify this class of genes, we de novo assembled unmapped reads from each field isolate and two laboratory strains (CC-125 and CC-1690) (Supplemental Table 3). We then performed ab initio gene prediction on the assembled contigs and applied a filter to remove potentially contaminating sequences and gene models without recognizable functional domains (see Methods; Supplemental Table 4). This set of predicted genes are expected to contain genes specific to the mt− mating type in strains of that mating type but should not contain chloroplast or mitochondrial genes because plastid genomes were added to the CC-503 reference assembly prior to read mapping.

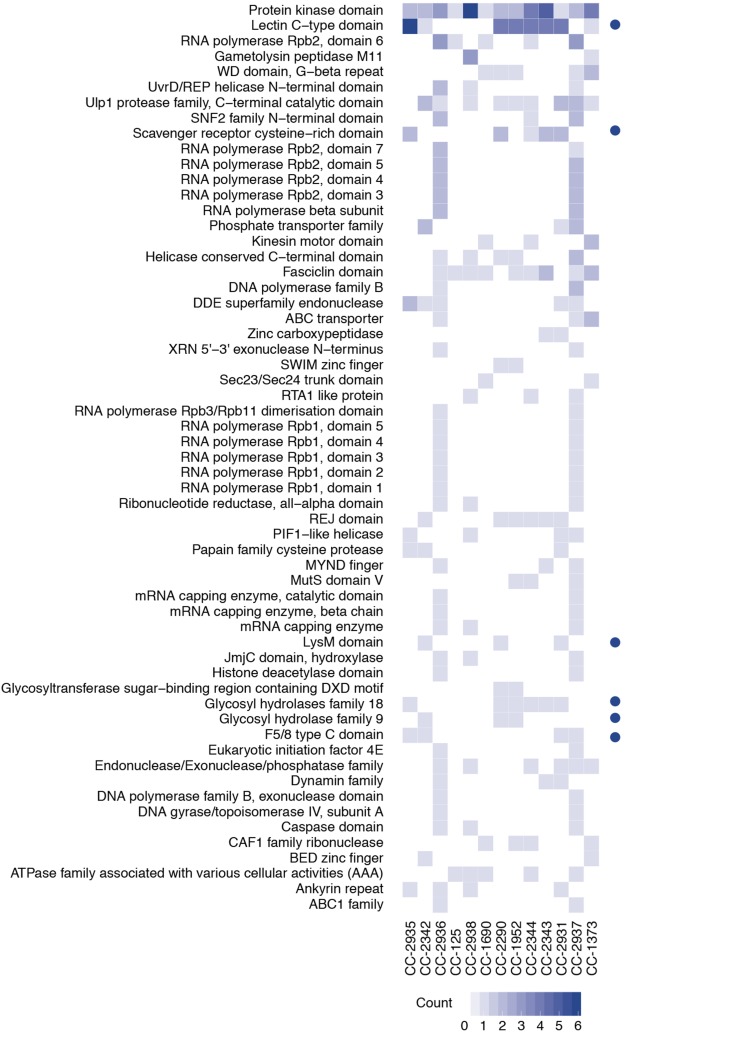

This approach yielded a set of candidate de novo-assembled loci for each strain that included 105 predicted domain families and the mating-type genes MID and MTD1 in mt− strains (Ferris et al., 2010). After application of filtering criteria (Supplemental Methods), we discovered an average of 32 novel genes per field isolate, ranging from 16 in CC-2344 to 39 in CC-2937 (Supplemental Table 3). Laboratory reference strains contained four novel genes in CC-125 (the progenitor strain to CC-503) and 12 in CC-1690. Many of the assembled genes represent putative carbohydrate recognition families, which were also prominent in the gene deletion set (i.e., relative to CC-503; Supplemental Data Set 6). These include putative carbohydrate recognition proteins LysM, F5/8 type C, WSC, scavenger receptor cysteine-rich (SRCR), and members of C-type lectin domain (CTLDs) gene families (Figure 4). In CC-2290, for example, 4 of 16 predicted genes in the de novo-assembled set have CTLD domains, which represents a significant enrichment of members of this gene family in this strain (P < 1.0 × 10−8) relative to the seven identified CTLD genes in CC-503. The complete unfiltered set of contigs and predicted proteins are archived in the Dryad Digital Repository (Supplemental Data Sets 9 and 10).

Figure 4.

De Novo-Assembled Gene Families in Chlamydomonas Strains.

Frequency of de novo-assembled gene families in the field isolates and two laboratory strains. Blue dots indicate putative carbohydrate recognition domain families. PFAM domain families found in at least two strains are shown. See data archived at the Dryad Digital Repository for a complete list of predicted genes, their domain family predictions, and the assembled contigs from each strain.

Evolution in the Laboratory

In addition to the field isolates, we examined genomic diversity among eight laboratory strains that are descendants of an original isolate from Massachusetts in 1945 (Harris, 2008). These strains are frequently considered to be clones due to a presumed shared ancestry, but we found them to harbor significant levels of polymorphism with 358,902 SNPs discovered in laboratory strains alone. A neighbor-joining tree based on the whole-genome SNP data largely recovered known or suspected relationships among laboratory strains, including close relationships of strains CC-1010 (UTEX90), CC-1690 (21gr), and CC-407, and strains CC-1009 and CC-408 (Figure 2B).

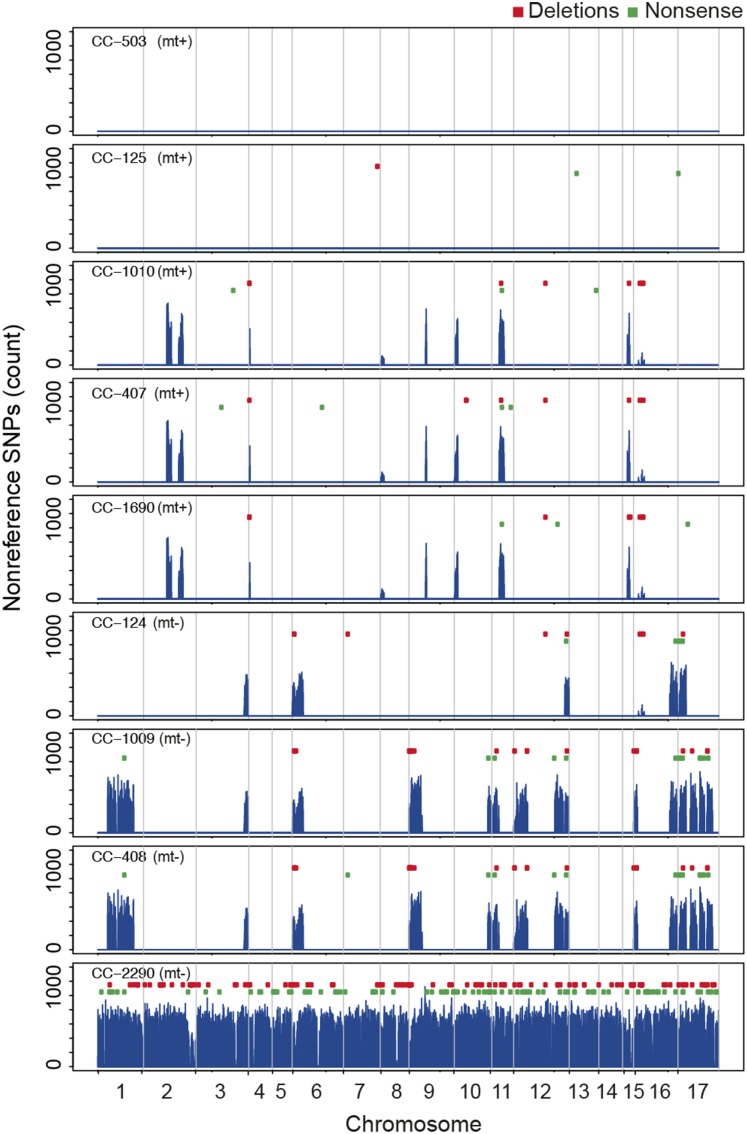

Variation segregating in these strains is unevenly distributed across the genome. Over much of the genome, the reference laboratory strains are identical-by-descent with the genome reference strain, CC-503, and the strain from which it is derived (i.e., CC-125). This is apparent in a plot of the genome-wide distribution of nonreference alleles that shows ∼20 megabase-scale segments where the reference laboratory strains are diverged from CC-503 (Figure 5). These variable regions include much of chromosome 17 in strains CC-1009 and CC-408, and the mating-type locus at the base of chromosome 6 in mt− strains CC-1009, CC-124, and CC-408 (Supplemental Table 5). These divergent segments are polymorphic for many of the same classes of major effect mutations observed in the field isolates. Gene deletions and nonsense mutations are restricted primarily to the diverged segments (Figure 5), which suggests that the majority of these mutations predate introduction to the laboratory. The mosaic patterning of polymorphism among laboratory strains has also been reported for mutant lines of Chlamydomonas (Dutcher et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2013) and is consistent with meiotic crossing-over between a heterozygous diploid zygospore collected by Smith in 1945, possibly followed by back- or outcrossing (Pröschold et al., 2005).

Figure 5.

Distribution of Nonreference SNPs in Laboratory Strains and CC-2290 (S1 D2) on 17 Chlamydomonas Chromosomes.

Regions of identity-by-descent between laboratory strains and CC-503/CC-125 are found intermittently with regions of divergence. CC-2290 is approximately uniformly diverged from CC-503 genome-wide. Chromosomal boundaries are indicated by vertical gray lines. Nonreference SNP counts are based on 25-kb nonoverlapping windows. Gene deletions (red) relative to CC-503 and “damaging” nonsense mutations (green) are represented as points above the nonreference SNP counts, showing that most mutations in these classes occur in the regions that are polymorphic in the laboratory reference strains.

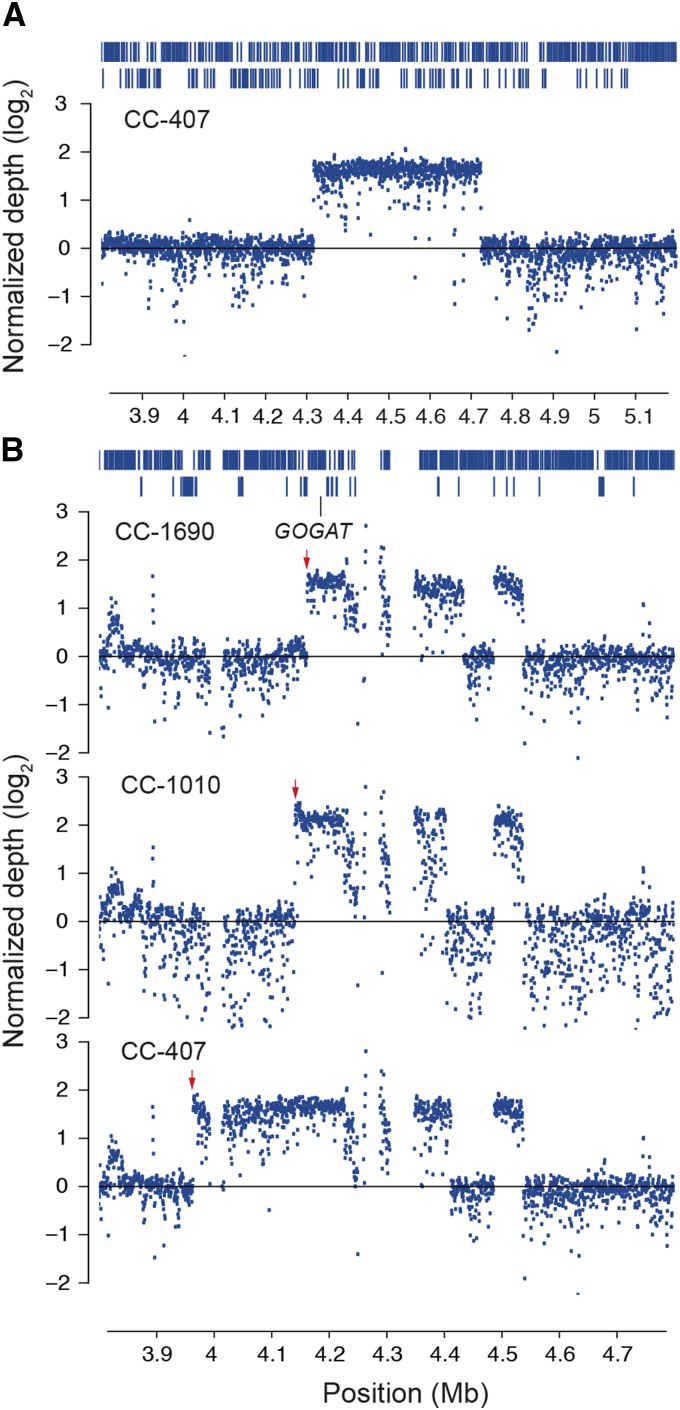

The most prominent class of laboratory-derived mutations are large-scale duplications of genomic regions that have anomalously high coverage compared with the genomic averages of individual strains. Using a normalized measure of read depth (see Methods), we localized the high coverage regions to well-delineated segments spanning tens to hundreds of kilobases (Figure 6; Supplemental Table 6) primarily on chromosomes 1, 10, 12, 13, and 17. For example, an ∼400-kb segment on chromosome 1 in CC-407 (Figure 6; Supplemental Table 6) represents a probable 3- or 4-fold amplification of this region that is unique to this strain. All of chromosome 1 in CC-407 is identical-by-descent with CC-503 and other mt+ strains (Figure 5), suggesting that this structural variant originated after introduction to the laboratory.

Figure 6.

Copy Number Variation in Chlamydomonas.

(A) Large candidate copy number gain on chromosome 1. Elevated normalized coverage depth with well-defined breakpoints between 4,318,500 and 4,725,000 bp in strain CC-407 suggest an ∼400-kb copy number gain in this region. Coverage is reported as the log2 of the normalized read depth (see Methods). Vertical lines/bars at the top of the panel represent individual genes. Genes are displayed as two rows where necessary to prevent overplotting.

(B) Copy number gains on chromosome 13 with unique breakpoints in three strains. Red arrows highlight three different break points at the 5′ end of each duplicated segment. A gene coding for the NADH-dependent form of glutamate synthase (GOGAT; Cre13.g592200.t1.2) is highlighted. Gaps in depth measurements represent missing sequences in the CC-503 reference assembly. Vertical lines/bars at the top of the panel represent individual genes. Genes are displayed as two rows where necessary to prevent overplotting.

A second region on chromosome 13 contains an apparent copy number gain shared by multiple strains (Supplemental Table 6). In this case, the 5′ breakpoint differs between strains (Figure 6) and could reflect multiple independent duplication events or recombination following a single initial duplication. Multiple independent origins of shared duplication regions have been observed in yeast when subject to laboratory growth conditions, and recurrent copy number gains may represent adaptive gain-of-function mutations (Gresham et al., 2010). The duplicated segment on chromosome 13 is shared across three strains and like the amplified region on chromosome 1 in CC-407 is found on a chromosome that is identical-by-descent across laboratory strains indicating that the mutation(s) likely arose in the laboratory.

In addition to these examples, both laboratory and field isolates show additional well-defined coverage depth anomalies suggestive of large scale duplication or amplification events (Supplemental Table 6). The field isolates CC-1952 and CC-1373 each have a large event spanning more than 400 kb at the tip of the long arm of chromosome 8. In addition, an event in CC-4414 on chromosome 1 shows well-demarcated differences in depth between halves of the chromosome—a pattern suggestive of a duplication of a chromosomal arm—and a second smaller anomaly at the base of chromosome 6. These events are unlikely to be due to artifacts in the CC-503 assembly (i.e., collapsed repeats) as all of the anomalous regions have normal coverage in most strains. The approximate physical boundaries of the largest candidate copy numbers gains are listed in Supplemental Table 6, and the normalized depth of coverage data (Supplemental Data Set 11) used to draw these conclusions are available at the Dryad Digital Repository. Characterizing the exact nature of these mutations will require a detailed examination of structural variation in these strains.

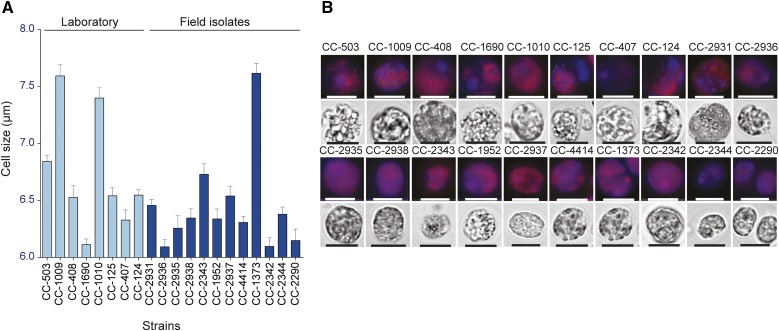

Phenotypic Variation among Chlamydomonas Strains

The extensive genetic diversity and cases of known phenotypic variation among isolates (Hoshaw and Ettl, 1966) suggest phenotypic differences are likely among strains of Chlamydomonas. Confocal images among strains do not show any gross morphological differences (Figure 7A), but we observe some visual differences particularly in cell size. We characterized cell size variation among strains by measuring cell diameter at mid-log phase in at least 1000 cells per strain and found significant variation in cell size among strains (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.0001; Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Phenotypic Variation in Cell Size in Chlamydomonas.

(A) Cell sizes of strains. Values represent means (+se) based on at least 500 cells per strain.

(B) Fluorescent and bright-field micrographs of each strain. DAPI fluorescence (blue) and chlorophyll fluorescence (red) are shown in the upper panels for each strain, created by overlay of the 655- and 448-nm filtered images. Bright-field images are shown in the lower panel for each strain. Bars = 7.5 μm.

We also examined growth rate differences among strains both under heterotrophic and phototrophic conditions. Each strain was grown in liquid Tris-acetate-phosphate (TAP) media in the presence of a tetrazolium dye (Chaiboonchoe et al., 2014) to measure growth rate based on active respiration from acetate uptake. We also measured phototrophic growth of four laboratory and four field strains by monitoring optical density. Although all strains were drawn from synchronized cultures and normalized for starting cell concentration, we found significant differences in heterotrophic growth rates (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.0001; Supplemental Figure 3) as well as phototrophic growth rates (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.0001; Supplemental Figure 4). Finally, there was also significant variation in chlorophyll content based on APC-A fluorescence (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.0001; Supplemental Figure 5). These results suggest phenotypic variation in growth rates and other features in both field isolates and closely related laboratory strains.

DISCUSSION

While much is known about the genetics of Chlamydomonas, relatively little is known about its ecology and evolution. Our sequencing of field isolates yields basic insights into the evolution of Chlamydomonas in its native environment that not only contribute to understanding of its population biology but can serve as a guide for experimental design. For example, evidence of population genetic structure suggests that gene flow between populations may be sufficiently low that populations can adapt to their local environment. Population structure sets the conditions necessary for adaptive divergence of important traits related to environmental responses such as the production of lipid in response to physiological stress. Evidence of structure provided here and elsewhere (Jang and Ehrenreich, 2012) therefore provides a rationale for design of quantitative trait loci mapping and experimental studies that should include strains from different source populations. Studies of the ecology and evolution of Chlamydomonas could prove particularly useful in applied settings, while further establishing the species as an evolutionary genetics model for the photosynthetic microalgae.

Genetic diversity in field isolates of Chlamydomonas is among the highest of known eukaryotes. Nucleotide diversity in the field strains (π = 0.028) is comparable to previous reports based on nuclear gene sequences (πintron = .027 [Liss et al., 1997; Sung et al., 2012], πsilent = 0.032, πintron = 0.033 [Smith and Lee, 2008]), although higher than estimates from other studies (Jang and Ehrenreich, 2012) (Table 5). Using this diversity estimate and two independent measures of the spontaneous mutation rate, μ, for Chlamydomonas (Ness et al., 2012; Sung et al., 2012), we estimate the effective population size, Ne = π/2μ, to be on the order of 108. This is among the highest known effective population sizes for any eukaryote with a direct estimate of the spontaneous mutation rate (Sung et al., 2012). The effective size of Chlamydomonas is therefore approximately one order of magnitude greater than yeast (Ne ∼107) and more than two orders of magnitude higher than Arabidopsis (Ne ∼250,000). Natural selection should therefore be more efficient at removing low fitness alleles in Chlamydomonas than these species. Consistent with this, the nonsynonymous to synonymous (N/S) ratio of 0.58 in Chlamydomonas is lower than Arabidopsis (N/S = 0.83; Clark et al., 2007) and other land plants (soybean, N/S = 1.61 [Lam et al., 2010]; rice, N/S = 1.29 [Xu et al., 2012]; sorghum, N/S = 1.0 [Mace et al., 2013]).

Table 5. Estimates of Nucleotide Diversity in Chlamydomonas in Previous Studies.

| Site Class | θπ | θw | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| All sites | 0.00190 | 0.0021 | Jang and Ehrenreich (2012); Vysotskaia et al. (2001)a |

| 0.01830 | – | ||

| Silent | 0.03190 | 0.0330 | Smith and Lee (2008) |

| Intron | 0.03350 | 0.0338 | Smith and Lee (2008); Jang and Ehrenreich (2012) |

| – | 0.0028 | ||

| Exons | 0.00600 | 0.0066 | Smith and Lee (2008); Jang and Ehrenreich (2012) |

| – | 0.0015 | ||

| UTRs | – | 0.0026 | Jang and Ehrenreich (2012) |

| Intergenic | – | 0.0011 | Jang and Ehrenreich (2012) |

| Intron | 0.02716 | – | Liss et al. (1997); Sung et al. (2012) |

Data are diversity estimates from nuclear genome sequences only. UTRs, untranslated regions.

Estimates based on comparison of strains S1 D2 and 137c (213 SNPs/11,651 sites).

Several classes of genes are noteworthy for having an excess of predicted major effect mutations, including proteins with either a receptor-like motif capable of carbohydrate binding (e.g., peptidoglycan and chito-oligosaccharides), a domain with hydrolytic activity (e.g., peptidase), or a combination of the two. A number of these genes were identified in our characterization of major effect mutations relative to CC-503 as well as in de novo assembly of unmapped reads (Figure 4). These include genes that encode proteins with CTLD, SRCR, and LysM domains, which frequently function as pattern recognition receptors in immunity, non-immunity-related signal transduction, and responses to cellular stress. For example, PAV is observed in genes g15210.t1 and Cre17.g736100.t1.3, which each have a carbohydrate-recognition domain (WSC and LysM, respectively) paired with a papain protease domain. The latter is interesting, since the plant LysM domain is found in the Medicago truncatula (barrel clover) and Arabidopsis receptor-like kinase CERK1 genes, as well as in CEBiP of O. sativa, where they are thought to function in perception of chitin (a microbe-associated molecular pattern) and are therefore members of signaling and response pathways active in defense against fungal attack (Kaku et al., 2006; Miya et al., 2007; Buist et al., 2008). While pathogen defense systems remain obscure in green algae, it is interesting to speculate that these genes may function as pattern recognition receptors, and, if so, may be involved in an ancestral form of cellular defense and subject to evolutionary pressures similar to other eukaryotic disease resistance genes. The high degree of presence/absence polymorphism in this group of genes is similar to the NBS-LRR family of disease resistance genes, which shows the highest level of gene PAV of any family of genes in land plants (Marone et al., 2013).

Chlamydomonas has a long history of laboratory culture, which began in 1945 when the ancestor of most laboratory strains was isolated in Amherst, Massachusetts and subsequently distributed to other laboratories (Harris, 2008). We found these strains to be genetic mosaics with genomic segments that are identical-by-descent with CC-503 intermittent with regions that are polymorphic among strains (Figure 5), a finding also observed in a larger study of laboratory strains in Chlamydomonas (Gallaher et al., 2015). This is consistent with crossing-over in an original heterozygous diploid zygospore that yielded recombinant progeny that were then distributed possibly with additional back- or outcrossing (Pröschold et al., 2005). The reference laboratory strains therefore constitute distinct genotypes each with a unique set of structural variants and other important classes of variation. These observations motivate a broader characterization of these and other strains derived from the original isolate (Gallaher et al., 2015) and imply that heterogeneous genetic backgrounds among strains should be considered in experimental designs.

The general absence of nucleotide variation in regions of identity-by-descent among laboratory strains indicates that few new mutations have arisen spontaneously in the laboratory over the past 70 years. However, copy number gains of large chromosomal segments represent one class of polymorphism that appears to have originated under laboratory culture conditions. These duplications potentially represent adaptations to the laboratory environment through mechanisms such as adaptive gene overexpression in culture (Gresham et al., 2008). For example, Chlamydomonas cells are frequently grown in liquid culture under constant light and subject to competition for nitrogen and other resources. This should favor mutations that improve nitrogen assimilation and sequestration of limiting nutrients. An interesting candidate in the amplified region on chromosome 13 (Figure 6B) is the gene encoding chloroplast-specific NADH-dependent glutamate synthase (GOGAT), a member of the pathway to sequester NH4+ lost during photorespiration. GOGAT is a member of the nitrogen assimilation pathway (Fernandez and Galvan, 2007) that mitigates losses of ammonia from photorespiration (Fischer and Klein, 1988). This gene is expressed in the chloroplast and responds to nitrogen deprivation with increased expression (Fuentes et al., 2001), and we suggest that high copy number may increase expression of GOGAT and provide growth advantages under competitive conditions. A similar pattern of gene amplification has been observed in laboratory evolution in yeast, where duplications of the glucose transporter gene HXT7 and a sulfate transporter SUL1 in response to glucose and sulfur limitation suggest adaptation of gene overexpression to laboratory culture conditions (Gresham et al., 2008).

Extensive diversity at neutral sites and in mutation classes with potentially significant phenotypic effects suggests that field strains harbor an enormous reservoir of functional variation. Naturally occurring alleles, including nonsense polymorphisms, TE insertion polymorphisms (Supplemental Data Set 1), and gene content polymorphism, provide a potentially rich source of variation for functional studies (Alonso-Blanco and Koornneef, 2000) that should complement artificially induced mutant libraries (Zhang et al., 2014; Jinkerson and Jonikas, 2015). Research into such natural variation has greatly assisted in discovery of valuable traits for crop improvement (Xu et al., 2006) and may also yield insight into the genetic basis of trait variation in Chlamydomonas (Alonso-Blanco and Koornneef, 2000).

There has been concerted interest in the last few years in the analysis of natural variation in plant species (Hunter et al., 2013; Marroni et al., 2014; Shi and Lai, 2015). Comparative studies of patterns of diversity can provide insights into the major factors that underlie mutational diversity among different plant taxa. We identify, for example, patterns of variation in gene classes as a function of whether they are ancient homologs that were found in the common ancestor between Chlamydomonas and Arabidopsis or are found only in the algal lineage. Our analysis in Chlamydomonas highlights some of the observed patterns of diversity in the photosynthetic algae and provides a foundation for a systematic analysis of natural variation across photosynthetic eukaryotes.

Finally, the SNPs we have identified may serve as a genomic resource that can be exploited to identify the genetic basis for trait variation. The extensive genomic and phenotypic diversity in traits including cell size, growth rate, and iron homeostasis (Gallaher et al., 2015) in both field isolates and reference laboratory strains warrants development of approaches to map the genes associated with specific traits. At present there are too few environmental isolates of Chlamydomonas to conduct genome-wide association studies, which have spurred recent developments in many areas of crop research. This highlights the importance of continued efforts to isolate new strains of Chlamydomonas (Nakada et al., 2014). Although conventional breeding and selection for desirable traits in Chlamydomonas and other algae, particularly for biofuel production, may progress slowly (Bonente et al., 2011), studies of natural isolates offer a potentially large and untapped reservoir of variation in heterogeneous genetic backgrounds that can be exploited in studies of gene function, quantitative trait loci studies, and targeted selection experiments.

METHODS

Strains

Field strains were chosen for genome sequencing to maximize the geographic extent of sampling within North America and to include two presumed clones CC-1952 and CC-2290 (S1 D2). Reference laboratory strains (i.e., common wild-type strains) were chosen based on their being well known and frequently studied by the Chlamydomonas reinhardtii research community (Table 1). Strains were obtained from the Chlamydomonas Resource Center at the University of Minnesota (http://chlamycollection.org/). Whole-genome sequences were obtained using a 2 × 51-bp sequencing strategy on an Illumina HiSeq 2000.

Genome Sequencing and Data Processing

A detailed description of library preparation, sequencing protocol, and analysis work flows is presented in the supplemental data. Cells were cultured in TAP liquid media and DNA extracted using Qiagen DNA plant Maxi kit (Qiagen). One microgram was used for paired end library preparation (2 × 51 bp) using an Illumina Truseq library preparation kit (Illumina), and sequencing was conducted on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 sequencer. Paired end reads were aligned using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA 0.6.1) (Li and Durbin, 2009) to the Chlamydomonas reference from JGI version 5 with the chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes added as baits for sequences missing from the reference assembly. Alignments were filtered and indel-realigned using the GATK (version 2.6-4). SNP calling was performed using GATK configured for a haploid organism and filters applied to reduce false positives (Supplemental Table 8). Functional annotations of SNPs and indels were inferred with snpEff v. 3.5a (Cingolani et al., 2012). Population genetic parameters were estimated using POPBam (Garrigan, 2013). Gene deletions were inferred by applying a coverage breadth criterion. Gene models with coverage breadth of at least 90% in the resequenced reference strain but <15% coverage breadth in one of the 19 nonreference strains were called deletions, and those with <50% coverage were called partial deletions. Copy-number gains were assessed by calculating normalized coverage in 499-bp intervals followed by manual inspection of depth variation along each chromosome. De novo assembly of unmapped reads was conducted using Velvet (Zerbino and Birney, 2008), as implemented by VelvetOptimizer (http://bioinformatics.net.au/software.velvetoptimiser.shtml) and contigs screened for contaminating sequences (see supplemental data). Ab initio gene prediction was conducted with Augustus (Stanke et al., 2004) and annotated using InterProScan 5 (Jones et al., 2014). Thirty-three predicted nonsense SNPs were checked using conventional PCR and Sanger-based sequencing (Supplemental Table 8). Statistical analysis was performed with R Statistical Programming Language v3.0. A detailed description of all methods is provided in the supplemental data.

Phenotypic Characterization of Strains

Cell size measurement and counting was performed using a Cellometer Auto M10 from Nexcelcom Bioscience. A total of 2 × 20 μL from each liquid algal sample was analyzed for mean diameter, based on counts of ∼500 live cells.

Relative DNA and chlorophyll content of Chlamydomonas cells were estimated through flow cytometry using a BD FACSAria III instrument. PBS buffer was used to load cells into the cytometer. Cells were passed through an 85-μm nozzle. Each of the 20 strains was stained with the nucleic acid stain 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and analyzed for fluorescence emission in the DAPI-A channel (excitation at 345 nm and emission at 450 nm). Chlorophyll content estimation was done through detecting the intrinsic chlorophyll fluorescence signal from the APC-A channel (excitation at 650 nm and emission at 660 nm). APC was used for chlorophyll detection since the highest emission intensity of chlorophyll is within the red fluorescence bandwidth range.

DAPI-stained cells were imaged using both lasers and fluorescent lamps as excitation sources with a two-photon microscope and a normal fluorescence microscope. Images were acquired on an Olympus Fluoview 1000 confocal laser scanning inverted microscope and an Olympus BX53. The microscopy provided a visual confirmation of the successful DAPI staining and chlorophyll fluorescence detection. Furthermore, it provided a rapid mean for qualitative determination of DNA and chlorophyll content localizations.

For heterotrophic growth rate measurements, modified Biolog phenotypic microarray (Biolog/Omnilog) experiments were performed. The Omnilog instrument generates growth curves by measuring the amount of color development produced by the NADH reduction of a tetrazolium-based redox dye. We followed a modified protocol from Chaiboonchoe et al. (2014). Modifications were as follows: (1) blank plates were used instead of substrate plates, and (2) three replicates of 20 strains (total of 60 wells) were inoculated in each plate. All cultures were grown in TAP media. We performed a nonlinear (least squares) curve fit to fit a straight line to the exponential phase of growth as recorded in the Omnilog instrument to obtain the predicted growth rate of each strain. We then compared the mean growth rate of each strain with using a one-way ANOVA test.

Phototrophic growth was measured using Multi-Cultivator MC 1000 photo bioreactor growth (Photon Systems Instruments). Cells were prepared as described above and per Photon Systems Instruments’ instructions included in the bioreactor setup guide. Briefly, cells were inoculated from solid agar media into liquid media for 24 h in illuminated flasks on a shaker. Ten mL of cells (concentration of ∼3 × 106 cells/mL) was inoculated into 40 mL of media in each bioreactor tube (50 mL total liquid volume in eight tubes/bioreactor setup) and illuminated with 400 μE (white LED light), and optical density readings were recorded at 680 nm every hour for 8 to 12 d. Bioreactors were maintained at 25°C throughout the course of the experiment.

Data Availability

Processed sample alignments and both unfiltered and filtered SNP call sets are available online for visualization via JBrowse (Skinner et al., 2009) at chlamy.abudhabi.nyu.edu.

Accession Numbers

Short read sequences were submitted to the NCBI Sequence Read Archive database at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/sra/sra.cgi with project number PRJNA271103 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA271103) and accession number SRP051522.

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Figure 1. Population genetic statistics on chromosomes of Chlamydomonas.

Supplemental Figure 2. Decay of linkage disequilibrium on 17 chromosomes of Chlamydomonas.

Supplemental Figure 3. Growth rates of strains under heterotrophic conditions.

Supplemental Figure 4. Growth rates for Chlamydomonas strains under phototrophic conditions.

Supplemental Figure 5. Chlorophyll content in strains of Chlamydomonas.

Supplemental Table 1. Summary of STRUCTURE (Pritchard et al., 2000) analyses.

Supplemental Table 2. Candidate major effect mutations in metabolic enzymes of Chlamydomonas.

Supplemental Table 3. Summary of de novo assembly results.

Supplemental Table 4. InterProScan5 predictions of PFAM domains for de novo-assembled contigs.

Supplemental Table 5. Genome segments in laboratory strains that are not identical-by-descent with CC-503.

Supplemental Table 6. Chromosomal breakpoints of large copy number gains in strains of Chlamydomonas relative to CC-503.

Supplemental Table 7. Summary of SNP-filtering protocol including cutoff thresholds.

Supplemental Table 8. PCR and Sanger-based sequencing validation of randomly selected nonsense SNPs.

Supplemental References. The following materials have been deposited in the DRYAD repository under accession number http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.1n0g6.

Supplemental Data Set 1. Transposable element insertion predictions relative to the CC-503 reference assembly based on RetroSeq (Keane et al., 2013).

Supplemental Data Set 2. Structural variant predictions based on the paired-end mapping approach of SVDetect (Zeitouni et al., 2010).

Supplemental Data Set 3. Summary of protein coding diversity in field isolates of Chlamydomonas.

Supplemental Data Set 4. Summary of πN and πS in field isolates of Chlamydomonas by functional category.

Supplemental Data Set 5. Genes with nonsense SNPs and the corresponding genotypes in field isolates and laboratory reference strains of Chlamydomonas.

Supplemental Data Set 6. Summary of gene deletion or partial deletion polymorphisms.

Supplemental Data Set 7. Coverage breadth matrix used to infer partial and complete gene deletions in field isolates and laboratory reference strains of Chlamydomonas.

Supplemental Data Set 8. Candidate major effect mutation counts by functional category.

Supplemental Data Set 9. De novo-assembled contigs from reads failing to map to the CC-503 reference assembly.

Supplemental Data Set 10. Predicted proteins from gene predictions on de novo-assembled contigs.

Supplemental Data Set 11. Normalized coverage depth in 499-bp genomic intervals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Paul Scheid, Ashish Agarwal, and Sebastien Modet who provided technical assistance with data acquisition and processing. We also thank Shenlong Wang, Sreedhar Manchu, Benoit Marchand, and Muataz Barwani of the NYU and NYUAD High Performance Computing teams. Rachid Rezgui from the NYUAD Core Technology Platform provided technical assistance with FACS experiments. Nizar Drou from the NYUAD Center for Genomics and Systems Biology set up JBrowse. This research was supported in part by grants from the NYU Abu Dhabi Research Institute (G1205), NYU Abu Dhabi Faculty Research Fund (AD060), the NYU Office of the Provost, and the National Science Foundation Plant Genome Research Program. U.R.'s contribution to this work was supported by a Human Frontier Science Program Postdoctoral Fellowship.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.D.P. and K.S.-A. conceived the study. M.D.P., K.S.-A., J.M.F., E.F.Y.H., and P.A.L. designed the study. G.M.P., K.M.H., U.R., T.B., B.K., D.R.N., K.J., and R.A. performed the experimental research. J.M.F. and K.M.H. analyzed the data. J.M.F., M.D.P., K.M.H., and K.S.-A. wrote the article.

Glossary

- TE

transposable element

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- PAV

presence/absence variant

- LOF

loss-of-function

- PCA

principal component analysis

- LD

linkage disequilibrium

- GO

Gene Ontology

- TAP

Tris-acetate-phosphate

- DAPI

4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

Footnotes

Articles can be viewed online without a subscription.

References

- Alonso-Blanco C., Koornneef M. (2000). Naturally occurring variation in Arabidopsis: an underexploited resource for plant genetics. Trends Plant Sci. 5: 22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begun D.J., et al. (2007). Population genomics: Whole-genome analysis of polymorphism and divergence in Drosophila simulans. PLoS Biol. 5: e310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaby I.K., et al. (2014). The Chlamydomonas genome project: a decade on. Trends Plant Sci. 19: 672–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonente G., Formighieri C., Mantelli M., Catalanotti C., Giuliano G., Morosinotto T., Bassi R. (2011). Mutagenesis and phenotypic selection as a strategy toward domestication of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii strains for improved performance in photobioreactors. Photosynth. Res. 108: 107–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan L., Owende P. (2010). Biofuels from microalgae-A review of technologies for production, processing, and extractions of biofuels and co-products. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 14: 557–577. [Google Scholar]

- Buist G., Steen A., Kok J., Kuipers O.P. (2008). LysM, a widely distributed protein motif for binding to (peptido)glycans. Mol. Microbiol. 68: 838–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J., et al. (2011). Whole-genome sequencing of multiple Arabidopsis thaliana populations. Nat. Genet. 43: 956–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaiboonchoe A., Dohai B.S., Cai H., Nelson, D.R., Jijakli K., Salehi-Ashtiani K. (2014). Microalgal metabolic network model refinement through high throughput functional metabolic profiling. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W.-H., Trachana K., Lercher M.J., Bork P. (2012). Younger genes are less likely to be essential than older genes, and duplicates are less likely to be essential than singletons of the same age. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29: 1703–1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cingolani P., Platts A., Wang L.L., Coon M., Nguyen T., Wang L., Land S.J., Lu X., Ruden D.M. (2012). A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster. Fly (Austin) 6: 80–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R.M., et al. (2007). Common sequence polymorphisms shaping genetic diversity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 317: 338–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutcher S.K., Li L., Lin H., Meyer L., Giddings T.H., Kwan A.L., Lewis B.L. (2012). Whole-genome sequencing to identify mutants and polymorphisms in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. G3 (Bethesda) 2: 15–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez E., Galvan A. (2007). Inorganic nitrogen assimilation in Chlamydomonas. J. Exp. Bot. 58: 2279–2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris P., et al. (2010). Evolution of an expanded sex-determining locus in Volvox. Science 328: 351–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer P., Klein U. (1988). Localization of nitrogen-assimilating enzymes in the chloroplast of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol. 88: 947–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes S.I., Allen D.J., Ortiz‐Lopez A., Hernández G. (2001). Over‐expression of cytosolic glutamine synthetase increases photosynthesis and growth at low nitrogen concentrations. J. Exp. Bot. 52: 1071–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallaher S.D., Fitz-Gibbon S.T., Glaesener A.G., Pellegrini M., Merchant S.S. (2015). Chlamydomonas genome resource for laboratory strains reveals a mosaic of sequence variation, identifies true strain histories, and enables strain-specific studies. Plant Cell 27: 2335–2352.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan X., et al. (2011). Multiple reference genomes and transcriptomes for Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 477: 419–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrigan D. (2013). POPBAM: Tools for evolutionary analysis of short read sequence alignments. Evol. Bioinform. 9: 343–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham B. (1997). Experimental evolution in Chlamydomonas. I. Short-term selection in uniform and diverse environments. Heredity 78: 490–497. [Google Scholar]

- Gresham D., Curry B., Ward A., Gordon D.B., Brizuela L., Kruglyak L., Botstein D. (2010). Optimized detection of sequence variation in heterozygous genomes using DNA microarrays with isothermal-melting probes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107: 1482–1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresham D., Desai M.M., Tucker C.M., Jenq H.T., Pai D.A., Ward A., DeSevo C.G., Botstein D., Dunham M.J. (2008). The repertoire and dynamics of evolutionary adaptations to controlled nutrient-limited environments in yeast. PLoS Genet. 4: e1000303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross C., Ranum L.W., Lefebvre P. (1988). Extensive restriction fragment length polymorphisms in a new isolate of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Curr. Genet. 13: 503–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Z., Steinmetz L.M., Gu X., Scharfe C., Davis R.W., Li W.-H. (2003). Role of duplicate genes in genetic robustness against null mutations. Nature 421: 63–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, E.H. (2008). The Chlamydomonas Sourcebook: Introduction to Chlamydomonas and Its Laboratory Use. (San Diego, CA: Academic Press). [Google Scholar]

- Harris E.H. (2001). Chlamydomonas as a model organism. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 52: 363–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand M., Abbriano R.M., Polle J.E.W., Traller J.C., Trentacoste E.M., Smith S.R., Davis A.K. (2013). Metabolic and cellular organization in evolutionarily diverse microalgae as related to biofuels production. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 17: 506–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hippler M., Redding K., Rochaix J.D. (1998). Chlamydomonas genetics, a tool for the study of bioenergetic pathways. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1367: 1–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshaw R.W., Ettl H. (1966). Chlamydomonas smithii sp. nov. - A Chlamydomonas interfertile with Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. J. Phycol. 2: 93–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hottes A.K., Freddolino P.L., Khare A., Donnell Z.N., Liu J.C., Tavazole S. (2013). Bacterial adaptation through loss of function. PLoS Genet. 9: e1003617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter B., Wright K., Bomblies K. (2013). Short read sequencing in studies of natural variation and adaptation. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 16: 85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang H., Ehrenreich I.M. (2012). Genome-wide characterization of genetic variation in the unicellular, green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. PLoS One 7: e41307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinkerson R.E., Jonikas M.C. (2015). Molecular techniques to interrogate and edit the Chlamydomonas nuclear genome. Plant J. 82: 393–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones P., et al. (2014). InterProScan 5: Genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 30: 1236–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jukes, T., and Cantor, C. (1969). Evolution of protein molecules. In Mammalian Protein Metabolism, H.N. Munro, ed (New York: Academic Press), pp. 571. [Google Scholar]

- Kaku H., Nishizawa Y., Ishii-Minami N., Akimoto-Tomiyama C., Dohmae N., Takio K., Minami E., Shibuya N. (2006). Plant cells recognize chitin fragments for defense signaling through a plasma membrane receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103: 11086–11091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa, M., and Goto, S. (2000). KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28: 27–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpowicz S.J., Prochnik S.E., Grossman A.R., Merchant S.S. (2011). The GreenCut2 resource, a phylogenomically derived inventory of proteins specific to the plant lineage. J. Biol. Chem. 286: 21427–21439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane T.M., Wong K., Adams D.J. (2013). RetroSeq: transposable element discovery from next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 29: 389–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J.K. (1997). A test of neutrality based on interlocus associations. Genetics 146: 1197–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K.M., Park J.-H., Bhattacharya D., Yoon H.S. (2014). Applications of next-generation sequencing to unravelling the evolutionary history of algae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 64: 333–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindle K.L. (1990). High-frequency nuclear transformation of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87: 1228–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korber B. (2000). HIV signature and sequence variation analysis. In Computational Analysis of HIV Molecular Sequences, Rodrigo A.G., Learn G.H., eds (Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; ), pp.55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Lam H.-M., et al. (2010). Resequencing of 31 wild and cultivated soybean genomes identifies patterns of genetic diversity and selection. Nat. Genet. 42: 1053–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leffler E.M., Bullaughey K., Matute D.R., Meyer W.K., Ségurel L., Venkat A., Andolfatto P., Przeworski M. (2012). Revisiting an old riddle: What determines genetic diversity levels within species? PLoS Biol. 10: e1001388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Durbin R. (2009). Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25: 1754–1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.H., et al. (2013). Molecular footprints of domestication and improvement in soybean revealed by whole genome re-sequencing. BMC Genomics 14: 579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H., Miller M.L., Granas D.M., Dutcher S.K. (2013). Whole genome sequencing identifies a deletion in protein phosphatase 2A that affects its stability and localization in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. PLoS Genet. 9: e1003841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind P.A., Farr A.D., Rainey P.B. (2015). Experimental evolution reveals hidden diversity in evolutionary pathways. eLife 4: e07074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liss M., Kirk D.L., Beyser K., Fabry S. (1997). Intron sequences provide a tool for high-resolution phylogenetic analysis of volvocine algae. Curr. Genet. 31: 214–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacArthur D.G., et al. (2012). A systematic survey of loss-of-function variants in human protein-coding genes. Science 335: 823–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mace E.S., et al. (2013). Whole-genome sequencing reveals untapped genetic potential in Africa’s indigenous cereal crop sorghum. Nat. Commun. 4: 2320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marone D., Russo M., Laidò G., De Leonardis A., Mastrangelo A. (2013). Plant nucleotide binding site-leucine-rich repeat (NBS-LRR) genes: Active guardians in host defense responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14: 7302–7326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marroni F., Pinosio S., Morgante M. (2014). Structural variation and genome complexity: is dispensable really dispensable? Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 18: 31–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]