Abstract

Phosphorylase kinase (PhK) is a hexadecameric (αβγδ)4 enzyme complex that upon activation by phosphorylation stimulates glycogenolysis. Due to its large size (1.3 MDa), elucidating the structural changes associated with the activation of PhK has been challenging, although phosphoactivation has been linked with an increased tendency of the enzyme's regulatory β‐subunits to self‐associate. Here we report the effect of a peptide mimetic of the phosphoryltable N‐termini of β on the selective, zero‐length, oxidative crosslinking of these regulatory subunits to form β–β dimers in the nonactivated PhK complex. This peptide stimulated β–β dimer formation when not phosphorylated, but was considerably less effective in its phosphorylated form. Because this peptide mimetic of β competes with its counterpart region in the nonactivated enzyme complex in binding to the catalytic γ‐subunit, we were able to formulate a structural model for the phosphoactivation of PhK. In this model, the nonactivated state of PhK is maintained by the interaction between the nonphosphorylated N‐termini of β and the regulatory C‐terminal domains of the γ‐subunits; phosphorylation of β weakens this interaction, leading to activation of the γ‐subunits.

Keywords: phosphorylase kinase, crosslinking, periodate, zero‐length crosslinking, subunit interactions

Abbreviations

- DFDNB

1,5‐difluoro‐2,4‐dinitrobenzene

- γCRD

C‐terminal regulatory domain of the γ‐subunit

- GMBS

N‐γ‐maleimidobutyryl‐oxysuccinimide ester

- Nβ peptide

synthetic peptide corresponding to the N‐terminal 22 residues of the β‐subunit

- PhK

phosphorylase kinase

- PKA

cAMP‐dependent protein kinase

Introduction

Phosphorylase kinase (PhK) is a key regulatory enzyme in the glycogenolysis cascade, catalyzing the Ca2+‐dependent phosphorylation and activation of glycogen phosphorylase in response to neural, hormonal, and metabolic signals.1 PhK, a member of the Ca2+/CaM‐dependent protein kinase family, is a 1.3 MDa hexadecamer composed of four copies of four subunits, α, β, γ, and δ. In nonactivated PhK the regulatory α, β and δ‐subunits exert quaternary constraint on the catalytic γ‐subunit, inhibiting its kinase activity.2, 3 Release of this constraint, that is, activation, is achieved through phosphorylation by cAMP‐dependent protein kinase, principally within the N‐terminus of the β‐subunit.4

Because of its large size and heterogeneous post‐translational modifications, a high resolution structure is not available for PhK. Low to moderate resolution methods for structure determination, such as electron microscopy, small‐angle X‐ray scattering, native MS, chemical crosslinking, and partial proteolysis, have illuminated approximate subunit locations and interactions in the PhK complex.5, 6, 7 The large, regulatory β‐subunits have been localized to the core of the complex, forming four central bridges that connect two octameric lobes [i.e., 2(αβγδ)2].5

One goal of our work has been to elucidate the structural mechanism for activation of the PhK complex by phosphorylation. Proximal regions of the β− and γ‐subunits have been shown to be structurally and functionally coupled, in that activators of PhK, including phosphorylation, increase solvent accessibility of epitopes on both subunits.8 Moreover, phosphorylation promotes global conformational changes in PhK that alter interactions among the β‐subunits within its β4 core and between its β‐ and γ‐subunits.7, 9 A large body of evidence points to the N‐terminus of β as an important regulatory region in the structural and functional coupling of β and γ. This region of β contains two phosphorylatable serines, 11 and 26, whose phosphorylation is associated with activation of the kinase.4, 10, 11, 12 Two approaches have shown that within the PhK complex the N‐terminus of β is proximal to both the C‐terminal regulatory domain of γ (γCRD) and to its active site. First, Lys‐303 within the γCRD is crosslinked to Arg‐18 at the N‐terminus of β by N‐[γ‐maleimidobutyrloxy]succinimide ester (GMBS).12 Second, autophosphorylation at the N‐terminus of β occurs intramolecularly, indicating that this region of β can bind directly to the active site of γ.13 The interaction of the N‐terminus of β with the γ‐subunit has also been studied using a synthetic peptide corresponding to the N‐terminal 22 residues of β (referred to herein as the Nβ peptide), which contains the phosphorylatable Ser‐11. Nβ peptide inhibited phosphoactivated PhK; and when present during crosslinking with GMBS, Nβ not only blocked crosslinking of β to γ, but was itself crosslinked to the same Lys in the γCRD as was the β‐subunit.12 These results indicate that the Nβ peptide is a true mimetic of the N‐terminus of β, competing for the same binding site(s) within the PhK complex. Phosphorylation of Ser‐11 on Nβ blocked the peptide's ability to inhibit phosphoactivated PhK.12

Given that previous work suggested that the N‐terminal region of β influenced both β–β and β–γ interactions in the PhK complex, our goal in this current study was to directly examine the effect on β self‐association of disruption of the β–γ interaction by the Nβ peptide. This approach required a highly selective crosslinker capable of forming β–β dimers in reasonable amounts within the intact PhK hexadecamer. Oxidative crosslinking, an emerging tool for studying protein–protein interactions,14 was the technique that was used to capture the β–β dimers. Oxidation of susceptible side chains can lead to reactive centers that are readily attacked by nearby nucleophiles, creating zero‐length crosslinks within a protein.15 The general oxidizing agent periodate was selected for this study because it was found to be highly selective and efficient in crosslinking PhK.

Results

Characterization of the products of periodate crosslinking

Periodate oxidation of PhK led to formation of three new species: a high molecular mass (∼180 kDa) crosslinked conjugate running slower than the heaviest subunit of PhK, and two low molecular mass species migrating slightly slower than the γ‐subunit (Fig. 1). The crosslinked heavy conjugate was determined to be intramolecular, as opposed to intermolecular (i.e., formed within 1 PhK hexadecamer as opposed to between 2), based on co‐elution of the crosslinked PhK with the native enzyme on a size exclusion column16 (data not shown). Because common buffer components are potentially susceptible to oxidation, we performed control reactions with alternative buffers and without sucrose and found that periodate still formed the same reaction products to the same extent, indicating that the modification of PhK was directly caused by periodate as opposed to a byproduct of periodate‐oxidized buffer components.

Figure 1.

Time‐dependent modification of PhK by periodate. (A) Coomassie stained 6–18% SDS PAGE, time course of crosslinking. (B) Percent change in the densities over time of the crosslinked β–β (•) and monomeric β (○) bands. Error bars represent standard deviation of triplicate samples.

The compositions of the three new species were determined using densitometry, apparent molecular masses, Western blot analyses, and N‐terminal sequencing. The time‐course of crosslinking shows a time‐dependent loss of the monomeric β and γ‐subunits, while the heavy crosslinked species appears at a rate similar to the loss of β before approaching a plateau at 15 min (Fig. 1). The α‐ and δ‐subunits, on the other hand, show no change in density over time, and thus manifest no evidence of participation in the periodate crosslinking. The apparent molecular mass of the heavy conjugate (180 kDa) is consistent with a β‐dimer (theoretical 220 kDa) or a βγγ‐trimer (theoretical 190 kDa). It should be noted, however, that crosslinked proteins may display a smaller apparent mass than the simple sum of their individual components due either to crosslinking in central regions of the polypeptides or to additional intra‐polypeptide chain crosslinking, both leading to smaller effective Stokes radii and thus faster migration. Western blots of the periodate‐modified enzyme, using subunit‐specific monoclonal antibodies for α, β, and γ (Fig. 2), revealed the heavy conjugate to be composed of only β, consistent with a β‐dimer.8 The three new species were N‐terminally sequenced, and γ was detected with high confidence in the two lighter bands only. The β‐subunit is acetylated at its N‐terminus and thus was not detected.10 To further confirm that the heavy conjugate is a β‐dimer, β was phosphorylated to a known extent by PKA and the resultant PhK crosslinked with periodate. If it is a β‐dimer, the specific radioactivity of the crosslinked product should be equivalent to the specific radioactivity of the monomeric β. If instead the heavy conjugate is composed of β and γ, its specific radioactivity would be expected to be lower than monomeric β. The specific radioactivities of the heavy conjugate and the β monomer corresponded, indicating that the heavy conjugate is composed entirely of β (data not shown). We therefore concluded that the heavy molecular mass species is a β‐dimer.

Figure 2.

Immunodetection of the α, β, and γ‐subunits in the products of periodate crosslinking of PhK for 10 min. 1, native PhK; 2, crosslinked PhK.

The cause of the plateau in β–β crosslinking after approximately 15 min is unknown. Although virtually all of the native γ is modified, over 50% of the monomeric β remains (Fig. 1). Importantly, addition of more periodate after crosslinking reached its plateau did not cause more β‐dimer to form, indicating that the plateau is not due to exhaustion of the periodate, but instead to an inability of the remaining β to be crosslinked. This could be explained by the presence of a subpopulation of β that is exclusively targeted by periodate, or alternatively oxidation of β over time leading to modification of the same amino acid residues that would have otherwise participated in crosslinking. We think that this second possibility is highly possible, given that at least eight different amino acids can be oxidized by periodate (see “Discussion”). Oxidation of any of these residues would be occurring simultaneously with, and could compete with, a crosslinking reaction by forming an oxidized dead‐end side chain incapable of crosslinking.

The two low molecular mass species formed by periodate oxidation appear to be composed entirely of γ (Fig. 2). The apparent molecular masses of these two species are 43 and 45 kDa, or 2 and 4 kDa heavier than native γ, respectively. Although the increase in apparent mass is consistent with conjugation with a small peptide, we found no evidence for this. The oxidative modification of γ likely causes the anomalous gel migration, as has been seen with oxidation of superoxide dismutase and is analogous to the altered migration frequently observed with other proteins after their phosphorylation.17, 18

PhK effectors and β crosslinking

Several small molecules, such as divalent cations and nucleotides, bind to PhK, and modulate its activity by bringing about conformational changes in the enzyme complex. Nucleoside diphosphates, in particular, are hypothesized to target the β‐subunit and promote conformational changes within the β‐core of the enzyme.19 We therefore crosslinked PhK with periodate in the presence of four known effectors: Mg2+, Ca2+, deoxyADP, and deoxyGDP. Deoxyribonucleotides were used instead of ribonucleotides to avoid oxidative cleavage of the ribose ring by periodate. Removal of the 3′ hydroxyl group from ADP does not significantly change its activating effect on PhK.19 Surprisingly, we found that β‐dimer formation was unchanged in the presence of these four known PhK effectors. There are several potential reasons for this, including the possibility that the crosslinked region of the 2β‐subunits does not change in the presence of these specific effectors, despite other conformational changes taking place elsewhere in the β‐subunits, as indicated by past studies.8, 20 Another possibility is that the effector binding sites on the enzyme are being oxidized, altering or eliminating binding before an effect on crosslinking is seen.

Nβ peptides and β crosslinking

The β‐subunits are the structural and regulatory core of the PhK enzyme complex,5 and their N‐termini have been shown to crosslink to the catalytic γ‐subunit, although the crosslinker used was relatively long.12 The synthetic Nβ peptide inhibited that β–γ crosslinking and was, in fact, crosslinked to γ itself, that is, even within the PhK complex it mimics and competes with the N‐termini of the β‐subunits to which it corresponds.12 Importantly, Nβ inhibits the kinase activity of phosphoactivated PhK, but not that of nonactivated PhK, while phospho‐Nβ inhibits neither form of the kinase.12 The sum of these results suggests that phosphorylation of the N‐terminal region of β diminishes its interaction with γ. Given that phosphorylation of the N‐terminus of β also promotes β self‐association,7, 9 we hypothesized that the Nβ peptide, by mimicking and competing with the N‐termini of the β‐subunits, would disrupt β–γ interactions in the nonactivated (nonphosphorylated) holoenzyme complex, thus inducing an increase in β‐dimer formation by periodate. As predicted, periodate crosslinking of PhK in the presence of the Nβ peptide caused an increase in β‐dimer formation (Fig. 3). Also as expected, phosphorylated Nβ peptide was considerably less effective in promoting β‐dimer formation (Fig. 3), which is consistent with our hypothesis that phosphorylation of the peptide inhibits its ability to compete with the native N‐terminus of β in interacting with the γ‐subunit.

Figure 3.

Nβ peptide and periodate crosslinking of the β‐subunits of PhK. (A) SDS PAGE of PhK treated with 500 μM periodate for 2.5 min in the presence of the Nβ peptide or phosphorylated Nβ peptide (1 mol αβγδ: 100 mol peptide). (B) Density of the β and β–β bands for the different conditions. The β densities are normalized to the monomeric β in native PhK and the β–β densities are normalized to the β–β in control crosslinked PhK (Xlink). Error bars represent standard deviation of quadruplicate samples.

Discussion

Herein we report the selective crosslinking of the large regulatory β‐subunits of PhK by the general oxidizing agent periodate. Although this oxidant is frequently used to cleave the carbon–carbon bond between vicinal hydroxyl groups in saccharides, we have successfully used low concentrations of periodate (≥10 µM) to oxidize susceptible amino acid side chains and thus introduce a zero‐length crosslink into the hexadecameric structure of nonactivated PhK, allowing the study of β‐subunit interactions. Although it would be useful to know the exact amino acids in β that are crosslinked, which we have achieved with other PhK crosslinkers,12, 21 that would not be trivial with periodate, given that it likely modifies numerous residues not involved in crosslinking. Periodate has been reported to oxidize the side chains of Tyr, Met, Trp, Cys, Asp, Asn, Arg, and His22, 23 but the only crosslink that has been characterized is a 3,3′‐dityrosine that it formed in ovotransferrin.24, 25 A variety of crosslinking reagents has been successfully used to study subunit interactions in PhK, but only two of these have been zero‐length, forming α–α, α–β, and γ–δ dimers.26, 27, 28 Zero‐length crosslinkers are desirable because they demonstrate that two subunits directly interact, as opposed to being only proximal. The only crosslinker previously shown to be selective for PhKs β−subunits was 1,5‐difluoro‐2,4‐dinitrobenzene (DFDNB), which has a 3‐5 Å spacer arm and also forms β–β dimers, but only in small amounts and only with activated conformers of PhK.9, 19 Because the 4β‐subunits form the four central bridges that interconnect PhKs two lobes,5, 6 the β‐dimers formed by periodate or DFDNB could be either intralobal or interlobal, as the subunits could potentially interact with each other within or across each lobe. Although we do not know the specific regions of β that DFDNB and periodate crosslink to form β‐dimers, it is likely that they target distinct areas of the subunit given their different responses to effectors of PhK on their crosslinking.9

The quaternary structure of nonactivated PhK inhibits the activity of its catalytic γ‐subunit2, 29, 30 (i.e., quaternary constraint), and subunit interactions within the complex are altered concomitant with enzyme activation7, 9, 12, 16 (i.e., relief of quaternary constraint). Overall, subunit interactions within the PhK complex are destabilized by phosphorylation, except for those of its β‐subunits, whose self‐association is strengthened,7 and it is the phosphorylation of β that is the key activator of PhK.4, 30 Within the hexadecameric PhK complex, regions of the β and γ‐subunits have been shown to be not only proximal,12 but to be structurally coupled to each other and with enzyme activation.8 Moreover, in native MS, β–β dimers are observed only in phosphoactivated PhK, whereas β–γ dimers are present in only nonactivated PhK.7 Thus, findings using multiple techniques link the phosphorylation of the N‐terminus of β with activation of γ and increased self‐association of β. The initiator of these linked events is the phosphorylation of the N‐terminus of β, and this region has, in fact, been shown to control β dimerization. In yeast two‐hybrid experiments designed to detect self‐association of β to form homo‐dimers, no self‐association was observed with full‐length β; however, removal of the first 31 residues from its N‐terminus or phosphomimetic Ser → Glu mutations in the N‐terminus of full length β both led to homodimerization.12 So, how might phosphorylation of this region of β relate to activation of γ? In addition to its being zero‐length, another major utility of periodate's crosslinking of PhK is that it targets a region of β that is sensitive to the interactions of its N‐terminus (Fig. 3), the site at which activating phosphorylation occurs. The sum of the above facts allows construction of a theoretical low resolution structural model for the activation of PhK by phosphorylation.

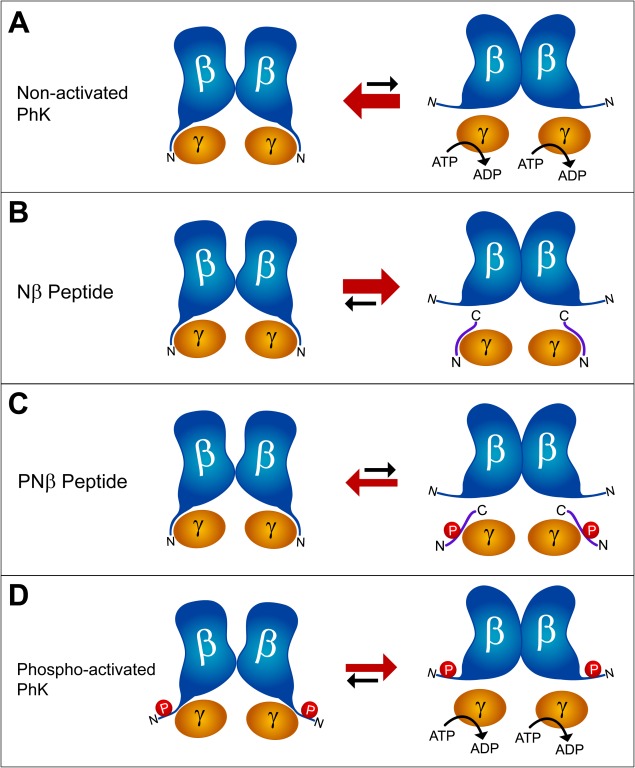

In this model (Fig. 4), we envision for the nonactivated enzyme a direct interaction between the γ‐subunit and the N‐terminus of β. This β–γ interaction can be thought of as an equilibrium between the nonactivated state of PhK (intact β–γ interaction and weak β‐subunit association) and an activated state (no, or limited, interaction between γ and the N‐terminus of β and enhanced β‐subunit self‐association). In the nonphosphorylated enzyme, the β–γ interaction would stabilize the nonactivated state of γ [Fig. 4(A)]. The above scenario is consistent with the findings that both the N‐terminus of β and the Nβ peptide crosslink to the C‐terminal regulatory region of γ, albeit with a 7.3–10 Å crosslinker.12 Previously, from results with peptide mimetics, the N‐terminus of β has been hypothesized to inhibit nonactivated PhK through either a direct or indirect interaction with γ.12, 31 In our model, successful competition of the Nβ peptide for the binding site on γ for the N‐terminus of the β‐subunit would free that N‐terminus and thus strengthen β self‐association [Figs. 3 and 4(B)]; however, the γ‐subunit would remain in the nonactivated state because it would still have the Nβ peptide bound to it [Fig. 4(B)]. Consistent with this last point, the Nβ peptide has no effect on the activity of nonphosphorylated PhK.12 Phosphorylation of the Nβ peptide is predicted to impair its binding to γ, thus it would compete poorly with the N‐terminus of the β‐subunit, leaving γ in the nonactivated state and not strongly promoting β self‐association [Figs. 3 and 4(C)]. Finally, we propose that phosphorylation of the N‐terminus of β at Ser‐11 or Ser‐26 disrupts the β–γ interaction, again leading to activation of γ and enhanced β self‐association [Fig. 4(D)]. Our model predicts that the Nβ peptide could readily bind to the γ‐subunit in this state and bring about inhibition, which is the case.12 It should be noted that in this model enhanced β self‐association is a consequence of activation, not its cause. It is attenuation of the interaction between the catalytic γ−subunit and the N‐terminus of β that gives rise to activation and the concomitant β‐dimerization detected by periodate oxidation. Thus, β‐dimers can be formed independently of activation when the Nβ peptide competes with and displaces the N‐terminus of the β‐subunit from γ (Fig. 3).

Figure 4.

Model for Activation of PhK. We propose a model for activation of PhK mediated by the phosphorylatable N‐terminus of the large, regulatory β‐subunits. In the nonactivated enzyme complex (A), the unphosphorylated N‐terminus of β interacts with the γ‐subunit, inhibiting kinase activity. In the presence of a competing peptide (Nβ), or phosphorylation, the N‐terminus of β loses strong contact with γ and promotes self‐association of the β‐subunits (B and D). The phosphorylated Nβ peptide does not compete as well for the interaction with γ (C).

Materials and Methods

PhK and Nβ peptide

Nonactivated PhK was purified from the psoas muscle of female New Zealand White rabbits, dialyzed into 50 mM HEPES (pH 6.8), 0.2 mM EDTA, and 10% sucrose (w/v), and stored at −80°C.32 The concentration of PhK was determined spectrophotometrically at 280 nM using an absorbance coefficient of 1.24 mL mg−1 cm−1.30 The Nβ and phosphorylated Nβ peptides were purchased from Biopeptide (San Diego, CA), and their purity and composition verified by both MS and MS/MS analyses using a MALDI 4700 mass spectrometer in the Mass Spectrometry Facility of the University of Kansas Medical Center.

Oxidative crosslinking

Sodium meta‐periodate (99.8+%, CAS No. 7790‐28‐5) was used as received from Acros Organics. Nonactivated PhK was incubated at 30°C for 2 min before periodate was added to initiate the crosslinking reaction. The standard final reaction mixture contained 20 mM HEPES (pH 6.8), 0.1 mM EDTA, 500 μM periodate and 1.35 μM αβγδ PhK promoter. When present, the peptide concentration was 135 μM. At appropriate times, aliquots of the reactions were removed and quenched in 125 mM Tris, 20% (v/v) glycerol, 5% (v/v) β‐mercaptoethanol, 4% (w/v) SDS, and trace Coomassie R250 (pH 6.8). Quenched samples were run on 6–18% gradient polyacrylamide gels, followed by staining with R250 Coomassie (0.1%) and Bismark Brown (0.02%) in 7% acetic acid, and 40% methanol. Gels were destained in 7% acetic acid and 5% methanol. Crosslinking reactions were carried out at least in triplicate with multiple preparations of PhK to confirm the reproducibility of the crosslinking. The density of the PhK subunits and crosslinked species was determined using ImageJ software.33

To prepare phosphoactivated PhK for crosslinking, the phosphorylation reaction (total volume of 80 μL) contained 54 mM β‐glycerophosphate (pH 7.0), 0.5 mM EGTA, 0.01 mM DTT, 50 mM NaF, 1.5 mM Mg(OAc)2, 0.25 mM [γ‐32P] ATP, 750 μg mL−1 PhK, and 2 μg mL−1 PKA (murine catalytic subunit, New England Biolabs, Cat. No. P6000L). The reaction was initiated by addition of Mg[γ‐32P]ATP, run at 30°C for 1 min, and quenched with 20 mM EDTA. The phosphate incorporation into β was 4× that into α (0.32 vs. 0.083 mol P/mol subunit). The quenched, phosphorylated PhK was immediately diluted into buffer containing a final concentration of 510 μM periodate and 437 μg mL−1 PhK. Crosslinking was carried out for 10 min at 30°C and quenched in SDS buffer. After running the samples on a 6–18% polyacrylamide gel, staining, and destaining, the α, β, and crosslinked product bands were excised, decolorized in 350 μL 30% H2O2 at 104°C for 1 h, and diluted in 4 mL scintillation fluid. The specific radioactivity of the bands were compared between crosslinked and noncrosslinked phosphoactivated PhK.

Apparent molecular mass determination

The apparent molecular masses of the crosslinked products were determined based on the relative mobilities on SDS‐PAGE gels of the native PhK subunits and protein standards. Using a broad range, molecular mass marker mix from Bio‐Rad (cat no. 161‐0318), the relative mobility was plotted against the log of the molecular mass for each protein or subunit. The resulting line had an R value of 0.99 and the corresponding linear equation was used to calculate the molecular mass of the crosslinked species from its relative mobility. For the theoretical masses of a β‐dimer and a βγγ‐trimer, the apparent molecular masses of each subunit were used, that is, the mass based on the relative mobility and not the actual mass of the subunits from amino acid compositions.

Western blots

Samples for immunodetection were transferred from the SDS‐PAGE gels to PVDF membranes and blocked with 5% (w/v) nonfat, powdered milk, PBS (0.14M NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 6 mM P i), 0.1% Tween20, and 0.2% gelatin, pH 7.4. The primary mAbs against the α, β, and γ‐subunits of PhK have been previously characterized and were used as described.8, 34 Colorimetric detection of the immunoreactive bands was performed with AP‐conjugated secondary antibodies from Southern Biotechnology.

N‐terminal sequencing

Crosslinked PhK was run on SDS‐PAGE, blotted on to PVDF, and stained with Ponceau S before the bands were excised and submitted to the Harvard University Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics Resource Laboratory (Cambridge, MA) for N‐terminal sequencing using Edman sequencing analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors declare that they have no conflicting interests. We thank Bill Lane and his colleagues at the Harvard Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics Resource Laboratory for their sequencing work.

Brief Description for Broader Audience: Obtaining detailed, structural information for large proteins is notoriously difficult. Zero‐length crosslinking is an especially valuable tool for studying subunit–subunit interactions in large enzyme complexes. Here we report highly selective zero‐length crosslinking within the large enzyme complex phosphorylase kinase. Utilization of a peptide mimetic with this crosslinking allowed us to devise a new model for activation of the enzyme.

REFERENCES

- 1. Pickett‐Gies CA, Walsh DA, Phosphorylase kinase. The enzymes, Vol. XVII In: Boyer PD, Krebs EG, Orlando FL, editors. (1986) New York: Academic Press, pp 395–459. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Paudel HK, Carlson GM (1987) Inhibition of the catalytic subunit of phosphorylase kinase by its α/β subunits. J Biol Chem 262:11912–11915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Burger D, Cox JA, Fischer EH, Stein EA (1982) The activation of rabbit skeletal muscle phosphorylase kinase requires the binding of 3 Ca2+ per δ subunit. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 105:632–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ramachandran C, Goris J, Waelkens E, Merlevede W, Walsh DA (1987) The interrelationship between cAMP‐dependent α and β subunit phosphorylation in the regulation of phosphorylase kinase activity. Studies using subunit specific phosphatases. J Biol Chem 262:3210–3218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nadeau OW, Lane LA, Xu D, Sage J, Priddy TS, Artigues A, Villar MT, Yang Q, Robinson CV, Zhang Y, Carlson GM (2012) Structure and location of the regulatory β subunits in the (αβγδ)4 phosphorylase kinase complex. J Biol Chem 287:36651–36661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nadeau OW, Gogol EP, Carlson GM (2005) Cryoelectron microscopy reveals new features in the three‐dimensional structure of phosphorylase kinase. Protein Sci 14:914–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lane LA, Nadeau OW, Carlson GM, Robinson CV (2012) Mass spectrometry reveals differences in stability and subunit interactions between activated and nonactivated conformers of the (αβγδ)4 phosphorylase kinase complex. Mol Cell Proteomics 11:1768–1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wilkinson DA, Norcum MT, Fizgerald TJ, Marion TN, Tillman DM, Carlson GM (1997) Proximal regions of the catalytic γ and regulatory β subunits on the interior lobe face of phosphorylase kinase are structurally coupled to each other and with enzyme activation. J Mol Biol 265:319–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fitzgerald TJ, Carlson GM (1984) Activated states of phosphorylase kinase as detected by the chemical cross‐linker 1,5‐difluoro‐2,4‐dinitrobenzene. J Biol Chem 259:3266–3274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kilimann MW, Zander NF, Kuhn CC, Crabb JW, Meyer HE, Heilmeyer LM Jr. (1988) The α and β subunits of phosphorylase kinase are homologous: cDNA cloning and primary structure of the β subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85:9381–9385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cohen P, Watson DC, Dixon GH (1975) The hormonal control of activity of skeletal muscle phosphorylase kinase. Amino‐acid sequences at the two sites of action of adenosine‐3':5'‐monophosphate‐dependent protein kinase. Eur J Biochem 51:79–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nadeau OW, Anderson DW, Yang Q, Artigues A, Paschall JE, Wyckoff GJ, McClintock JL, Carlson GM (2007) Evidence for the location of the allosteric activation switch in the multisubunit phosphorylase kinase complex from mass spectrometric identification of chemically crosslinked peptides. J Mol Biol 365:1429–1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. King MM, Fitzgerald TJ, Carlson GM (1983) Characterization of initial autophosphorylation events in rabbit skeletal muscle phosphorylase kinase. J Biol Chem 258:9925–9930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kodadek T, Duroux‐Richard I, Bonnafous JC (2005) Techniques: oxidative cross‐linking as an emergent tool for the analysis of receptor‐mediated signalling events. Trends Pharm Sci 26:210–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Peerey LM, Kostic NM (1987) Transition–metal compounds as new reagents for selective cross‐linking of proteins‐synthesis and characterization of 2 bis(cytochrome‐c) complexes of platinum. Inorg Chem 26:2079–2083. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nadeau OW, Sacks DB, Carlson GM (1997) Differential affinity cross‐linking of phosphorylase kinase conformers by the geometric isomers of phenylenedimaleimide. J Biol Chem 272:26196–26201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee CR, Park YH, Kim YR, Peterkofsky A, Seok YJ (2013) Phosphorylation‐dependent mobility shift of proteins on SDS‐PAGE is due to decreased binding of SDS. Bull Korean Chem Soc 34:2063–2066. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fujiwara N, Nakano M, Kato S, Yoshihara D, Ookawara T, Eguchi H, Taniguchi N, Suzuki K (2007) Oxidative modification to cysteine sulfonic acid of Cys111 in human copper‐zinc superoxide dismutase. J Biol Chem 282:35933–35944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cheng A, Fitzgerald TJ, Carlson GM (1985) Adenosine 5'‐diphosphate as an allosteric effector of phosphorylase kinase from rabbit skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem 260:2535–2542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nadeau OW, Carlson GM, Gogol EP (2002) A Ca2+‐dependent global conformational change in the 3D structure of phosphorylase kinase obtained from electron microscopy. Structure 10:23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nadeau OW, Wyckoff GJ, Paschall JE, Artigues A, Sage J, Villar MT, Carlson GM (2008) CrossSearch, a user‐friendly search engine for detecting chemically cross‐linked peptides in conjugated proteins. Mol Cell Proteomics 7:739–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jackson EL (1944) Periodic acid oxidation. Organic reactions. New York: Wiley, pp 2. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nakamura S, Hayashi S, Koga K (1976) Effect of periodate oxidation on structure and properties of glucose oxidase. Biochim Biophys Acta 445:294–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hsuan JJ (1987) The cross‐linking of tyrosine residues in apo‐ovotransferrin by treatment with periodate anions. Biochem J 247:467–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nadeau OW, Falick AM, Woodworth RC (1996) Structural evidence for an anion‐directing track in the hen ovotransferrin N‐lobe: implications for transferrin synergistic anion binding. Biochemistry 35:14294–14303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nadeau OW, Carlson GM (1994) Zero length conformation‐dependent cross‐linking of phosphorylase kinase subunits by transglutaminase. J Biol Chem 269:29670–29676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nadeau OW, Traxler KW, Carlson GM (1998) Zero‐length crosslinking of the β subunit of phosphorylase kinase to the N‐terminal half of its regulatory α subunit. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 251:637–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jeyasingham MD, Artigues A, Nadeau OW, Carlson GM (2008) Structural evidence for co‐evolution of the regulation of contraction and energy production in skeletal muscle. J Mol Biol 377:623–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hayakawa T, Perkins JP, Krebs EG (1973) Studies of the subunit structure of rabbit skeletal muscle phosphorylase kinase. Biochemistry 12:574–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cohen P (1973) The subunit structure of rabbit‐skeletal‐muscle phosphorylase kinase, and the molecular basis of its activation reactions. Eur J Biochem 34:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Newsholme P, Angelos KL, Walsh DA (1992) High and intermediate affinity calmodulin binding domains of the α and β subunits of phosphorylase kinase and their potential role in phosphorylation‐dependent activation of the holoenzyme. J Biol Chem 267:810–818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. King MM, Carlson GM (1981) Synergistic activation by Ca2+ and Mg2+ as the primary cause for hysteresis in the phosphorylase kinase reactions. J Biol Chem 256:11058–11064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW (2012) NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods 9:671–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wilkinson DA, Marion TN, Tillman DM, Norcum MT, Hainfeld JF, Seyer JM, Carlson GM (1994) An epitope proximal to the carboxyl terminus of the α‐subunit is located near the lobe tips of the phosphorylase kinase hexadecamer. J Mol Biol 235:974–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]