Abstract

Arginine methylation is important in biological systems. Recent studies link the deregulation of protein arginine methyltransferases with certain cancers. To assess the impact of methylation on interaction with other biomolecules, the pK a values of methylated arginine variants were determined using NMR data. The pK a values of monomethylated, symmetrically dimethylated, and asymmetrically dimethylated arginine are similar to the unmodified arginine (14.2 ± 0.4). Although the pK a value has not been significantly affected by methylation, consequences of methylation include changes in charge distribution and steric effects, suggesting alternative mechanisms for recognition.

Keywords: arginine, methylation, methyltransferase, pKa determination, pH titration, NMR spectroscopy

Introduction

Molecular recognition of proteins plays an important role in chemistry and biology. Contacts occur on the protein surface and may involve other proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, sugars, and other ligands. Although the majority of polar and charged residues are located on the protein surface, ionizable groups are also found in the hydrophobic protein interior and lipid membranes. Arginine is one of the most frequently buried charged residues.1, 2, 3 The guanidinium group of arginine contains a positive charge that is retained even at elevated pH in the interior of proteins and lipid bilayers.4, 5, 6 In addition, this group contains favorably positioned hydrogen bond donors that can be methylated by a family of enzymes called protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs).7

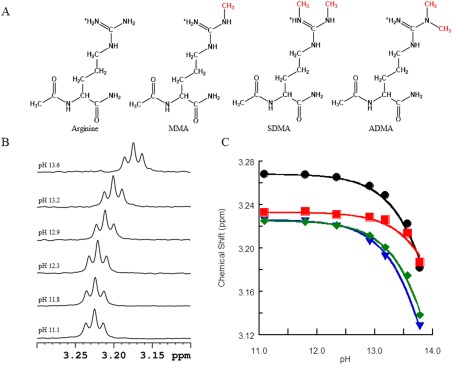

Arginine is subject to several post‐translational modifications including methylation, resulting in monomethylarginine (MMA), asymmetric dimethylarginine (aDMA), and symmetric dimethylarginine (sDMA; Fig. 1).7 Methylation of arginine is biologically relevant, as much as 2% of arginine residues are methylated in rat liver nuclei,8 and deregulation of PRMTs has been linked to a number of diseases including cancer.7, 9 Methylation of arginine is important in nucleic acid binding, processing, and gene regulation.7 Arginine residues interact with the nucleic acid phosphate backbone and commonly form hydrogen bonds with the base residues, particularly guanine, in protein–DNA complexes.10 The methylation and subsequent removal of potential hydrogen bond donors disrupts this network of hydrogen bonds, potentially inhibiting binding.7 In addition to the removal of an important hydrogen bond donor, shape, hydrophobicity, and affinity to aromatic rings are affected, modulating regulation of transcription factors and histones.11, 12 PRMT substrates have also been associated in a number of important DNA repair processes from double‐strand break repair13 to potential regulation of Pol‐β, implicated in base excision repair.7, 14, 15

Figure 1.

A: Arginine and methylated arginine variants. N‐ and C‐termini contain protection groups to mimic a peptide environment. B: 1H NMR (600 MHz) of the delta protons of 0.5 mM MMA at 25°C from pH 13.6 to 11.1 (top to bottom). C: 1H NMR pH titration of aDMA (black), sDMA (red), MMA (green), and protected control arginine (blue) delta protons.

Methylation could potentially perturb the pK a of the arginine side chain and, hence, the charge of the guanidinium moiety. In a protein, the charge state may be further modulated by the local environment. In less polar microenvironments, the pK a of internal residues shifts to favor neutral species.16 Lysine residues, for example, have observable pK a values that have shifted from 10 to around 5.17 Arginine residues, however, retain their charge even at pH 10.5 For a proper comparison of pK a shifts, the unperturbed values must be known.

The pK a of arginine has been difficult to determine with certainty. Although a generally accepted pK a of 12.48 has been reported in journals and texts since its publication in 1930, previous studies with arginine range from 11.5 to 14.18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 The wide range of published values is a good indication of the difficulties in measuring the pK a of such a system. In contrast to potentiometric methods, NMR spectroscopy facilitates pK a determination at extreme pH values.32, 33, 34

We have shown, through NMR titrations, that methylation does not affect the pK a of the arginine side chain. This implies that functional consequences of methylation arise not because of a change in the charged state, but by other means. We further probe the effect of methylation by comparing the volume, log P, and electrostatic potential maps of the methylated variants to simulate the contribution of steric bulk, change in hydrophobicity, and charge distribution.

Results

To investigate the effect of methylation, 1H NMR spectra of four arginine variants (Fig. 1) were observed at different pH values. The pH of each sample was calculated using concentrated KOH and then confirmed using a glass pH electrode appropriate for high pH. Ligand concentration and volume were kept constant to minimize systematic errors.32 In addition, the ionic strength was kept at 1.0 M for each NMR sample with KOH/KCl. This electrolyte pair was selected on the basis of having less self‐association, when compared with NaOH, and an overall higher pK w with the use of KOH.32, 35 The titration was conveniently monitored from the chemical shift of the delta protons of arginine near 3.25 ppm [Fig. 1(B)]. These protons are in close proximity to the charged guanidinium group and experience no overlap in that region of the 1H NMR spectra. In addition, the chemical shifts of the methyl peaks were also monitored for MMA, sDMA, and aDMA (Fig. 3). Furthermore, natural abundance 13C NMR was also measured for the protected arginine control and arginine, prepared using the same method as before, but with 50 mM arginine concentrations to validate the higher observed pK a trends (Fig. 4 and Supporting Information Fig. S1). The numerical values were estimated using a Henderson‐Hasselbalch equation modified for NMR titrations and adapted from a pK a study in 2007,34 where δ obs is the observed chemical shift, δ HA and δ A− are chemical shifts of the protonated and unprotonated species, respectively, and χ is the mole fraction:

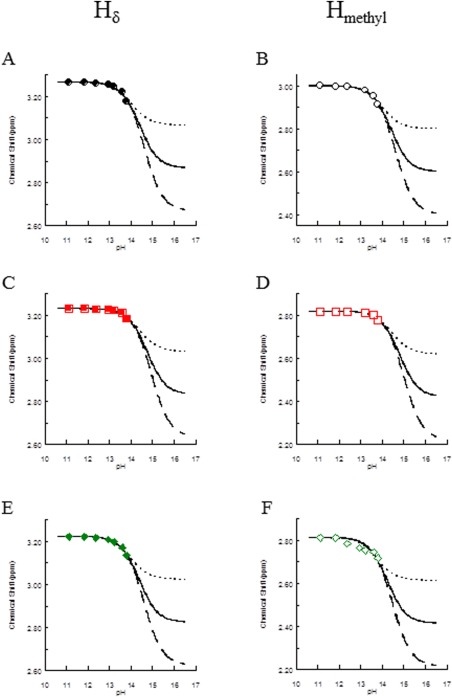

Figure 3.

Titration curves for 1Hδ and 1Hmethyl as a function of pH for 0.5 mM (A and B) aDMA, (C and D) sDMA, and (E and F) MMA. For each plot, experimental data are represented by data points, closed for delta proton chemical shifts and open for methyl proton chemical shifts, solid black lines are for estimated unprotonated species (0.4 ppm difference from the protonated species), dotted lines are for estimated unprotonated species (0.2 ppm difference from the protonated species), and dashed lines are for unprotonated species (0.6 ppm difference from the protonated species). Data were collected on a 5‐mm QXI probe at 600 MHz.

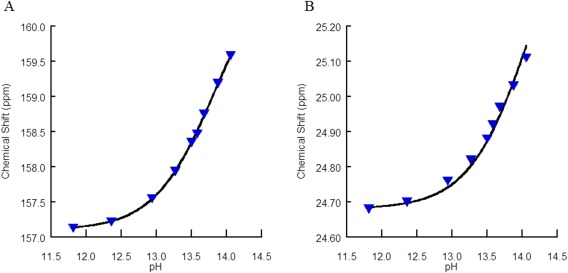

Figure 4.

Titration curves for the control arginine for natural abundance (A) 13Cζ and (B) 13Cγ chemical shifts for 50 mM control arginine with additional amide group at the C‐terminus and acetyl at the N‐terminus to mimic a peptide environment. Because degradation at the backbone was observed, data points above pH 14.04 were not recorded. The Δδ used were from previously reported values of 4 and 1 ppm,24 yielding pK a values of 13.8 and 14.1, respectively. Data were collected using a 10‐mm BBO probe at 150.9 MHz.

The 1H NMR titration curves shown in Figure 1(C) show that all arginine variants behave similarly and that the titrations do not reach completion even at the highest pH, a clear indication of a pK a > 12.5.

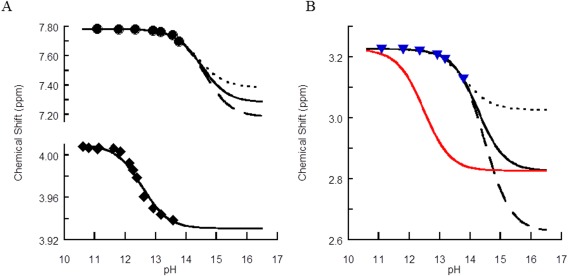

Two control compounds with previously published high pK a values were also measured to demonstrate the validity of the method and reagents; imidazole, with a pK a of 14.5,36 and trifluoroethanol, with a pK a near 12.5,31 were prepared as previously described. A complete titration curve that did not require the estimation of the chemical shift of the unprotonated species was obtained for trifluoroethanol resulting in a pK a of 12.5 in agreement with the published data (Table 1 and Fig. 2). Because the titration could not be completed due to pH limitations in aqueous solutions and degradation of the protected arginine, the chemical shifts of the unprotonated species of imidazole and the arginine variants could not be directly obtained from the curves and were therefore computationally assessed for a range of chemical shifts (Figs. 2 and 3). The chemical shifts of protonated and unprotonated species were obtained from Spartan 10 using a Hartree‐Fock 6‐31G* basis set. For imidazole, an average chemical shift difference of 0.6 ppm was found, whereas the difference was 0.5 ppm for the arginine variants (black lines). A previous publication reported a difference between protonated and unprotonated species of 0.2 ppm.24 We therefore calculated pK a values for 0.2–0.6 ppm to assess the impact of uncertainty in the chemical shift difference (Fig. 2). Note that even if the unprotonated species had unrealistically low chemical shift differences (∼0.1 ppm) that the pK a would still be > 13.5. For imidazole [Fig. 2(A)], the pK a was estimated at 14.6 ± 0.3, in reasonable agreement with literature value of 14.5 for the second deprotonation of neutral imidazole to its anion form using this validated procedure; imidazole has two pK a values, 7.0 and 14.5. The unmethylated arginine (Fig. 2) has a pK a of 14.2, when compared with the 14 pK a of arginine in a tripeptide from published NMR titrations.24 MMA, sDMA, and aDMA had pK a values from delta protons of 14.3, 14.7, and 14.3, respectively (Table 1). For the methylated arginine derivatives, these values were further supported from the chemical shift changes of the methyl protons (Fig. 3). Because of the unconventionally elevated pK a values, we also measured the natural abundance 13C chemical shifts as a function of pH for the protected arginine control (Fig. 4) and for arginine (Supporting Information Fig. S1). The pK a estimated using a Δδ of 4 ppm for 13Cζ and 1 ppm for Δδ 13Cγ carbons using previously published ranges gave pK a values of 13.8 and 14.1, respectively, in agreement with the previously published arginine pK a in a tripeptide.14

Table 1.

Extrapolated pKa Values for the Four Modified Arginine Variants and Control Compounds Imidazole and Trifluoroethanol (TFE)

| pK a a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Titrant | Hδ | Hmet | H2,4/5 | H |

| Arginine | 14.2 | — | — | — |

| MMA | 14.3 | 14.1 | — | — |

| sDMA | 14.7 | 14.7 | — | — |

| aDMA | 14.3 | 14.3 | — | — |

| Imidazole | — | — | 14.6, 14.8b | — |

| TFE | — | — | — | 12.5 |

Values are based on a plot of 1H NMR chemical shifts as a function of pH.

Error of ±0.3 imidazole and ±0.4 for each arginine variant was estimated from a model fit. Note that lower values were calculated if using a previously published Δδ of 0.2 ppm for arginine, yielding 13.8, 14.0, 14.0, and 14.4 for the arginine variants shown in the table; however, higher Δδ better fit the experimental data for the modified variants.

Chemical shifts were monitored for H2 and H4/H5 of imidazole, yielding pK a values of 14.6 and 14.8, respectively.

Figure 2.

Titration curves for (A) control compounds and (B) the protected control arginine. Monitoring the chemical shift and pH for (A) H2 of imidazole (top) and trifluoroethanol (bottom) and (B) Hδ of arginine with a simulated curve for a hypothetical pK a of 12.48 (red trace). Experimental data are represented by circles for imidazole (A) and by diamonds for trifluoroethanol and (B) blue triangles for arginine. The lines are for simulated curves, assuming a difference in chemical shift between the protonated and unprotonated species of 0.2 (dotted), 0.4 (solid), and 0.6 (dashed) ppm for the arginine variants, and 0.4, 0.5, and 0.6 ppm for imidazole.

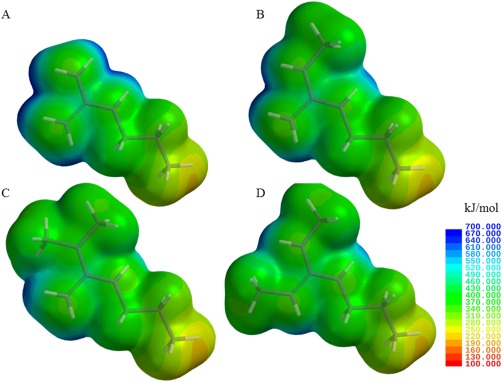

As methylation does not markedly change the pK a of the guanidinium head group of arginine, altered molecular interaction with methylated arginines are not likely due to differences in charge. Methylation affects the hydrogen bonding properties, and thus, protein–protein, peptide lipid, and protein–ligand interactions, as shown by previous studies.37, 38, 39 Methylation also alters steric factors, hydrophobicity, and charge distribution of the guanidinium head group (Fig. 5). To further evaluate some of these properties, we used Spartan to calculate the alteration of the electrostatic potentials, volume, and hydrophobicity in terms of log P (Fig. 5). Tautomers for each variant were constructed and individually minimized; each lowest energy tautomer is shown in Figure 5. The introduction of a bulky moiety affects the overall volume of the head group, introducing steric hindrance; in our model constructs, this is represented by an increase of 17, 33, and 34% for MMA, aDMA, and sDMA with respect to the control. Both the unmethylated and monomethylated models have similar charge distribution. In comparison, both dimethylated constructs show electrostatic potential maps with different and more diffuse charge localization. The charge distribution in each structure is affected by methylation, which may result in altered interactions with proteins or nucleic acids. The hydrophobicity of the molecules, described by the term log P, increases significantly from a negative value of −0.34, as expected for a charged molecule in the control, to positive values of 0.18, 0.56, and 0.70 for the MMA, aDMA, and sDMA model constructs.

Figure 5.

Electrostatic potential maps of guanidinium head groups calculated using Spartan 10. The constructs shown above depict representative shortened, model structures of the four arginine variants: (A) unmethylated, (B) MMA, (C) aDMA, and (D) sDMA. The color scale for the electric potentials is shown in kilojoules per mole, where red represents the lowest electrostatic potential (electron rich) and blue represents the highest electrostatic potential (electron poor) regions. Tautomers for each variant were constructed and individually minimized; the lowest energy tautomer is shown.

Discussion

An understanding of the charge state of arginine and methylated arginine derivatives is crucial in understanding the mechanisms and functions of arginine and its derivatives in biological systems. In this study, we have found pK a values of free arginine and methylated arginine derivatives in water near 14. This implies that in a biological environment, the arginine side chain is fully charged regardless of the methylation state. The placement of the methyl groups on the nitrogen groups does not have an appreciable impact on the pK a, with the possible exception of sDMA; however, the pK a differences for sDMA and aDMA are less than 0.5. This finding is supported by a report where guanidine and methylated guanidine derivatives were all found to have similar pK a values by potentiometric titrations of around 13.6–13.840 and by a similar NMR study to probe the pK a of methylated lysine residues on Ca2+‐bound and apo‐calmodulin where variation in pK a between dimethylated and monomethylated lysine species were reported to be <0.8 pH units.41

The pK a of the arginine side chain has been a topic of several studies beginning in the early 20th century. Although an extensively quoted value of 12.48 has been found in literature and textbooks since 1930, published results have ranged from 11.5 to 14.18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 The experimental determination of arginine's third pK a has been notoriously difficult, with few published studies citing measured pK a values using alternative methods until very recently. A study in 2007 attempted to determine pK a of lysine and arginine on apo‐calmodulin using NMR titrations; they reported only slight chemical shift perturbations for arginine at pH 12.5, indicating that the pK a has not yet been reached.34 In addition, several groups have recently published simulated or predicted arginine or guanidine variants pK a values with mixed results ranging from 12.5 to 16.1.42, 43, 44, 45, 46 Recently, the pK a of free arginine using potentiometry and arginine using 1H, 13C, and 15N NMR titrations was published at ≥13.8.24 Although this value is somewhat lower than the one reported here, it was stated that the reported value of 13.8 could be an underestimation. Moreover, the endpoint of our variants could not be reached due to degradation of the backbone mimic; we therefore estimated the chemical shift of the unprotonated species, and we report an average pK a from a range of Δδ 0.2–0.6 ppm.

Arginine is frequently methylated, with PRMTs involved in a number of important biological processes. In this study, we have shown that arginine methylation modulates interactions not by a change in charge or pK a. Methylation results in an increase in volume of the head group and alters the charge distribution, hydrophobicity, and the potential to form hydrogen bonds, all of which impact binding and recognition with a variety of targets.38, 39 These properties are also used to discriminate between the different methylated ligands such as aDMA and sDMA.12, 37, 47, 48

Materials and Methods

The arginine variants for the 1H NMR were synthesized by solid‐phase synthesis using rink amide resins, with acetic anhydride used for capping. Following the TFA cleavage, the crude products were purified by reverse‐phase HPLC, and the products were confirmed through ESI‐MS. The protected control arginine variant with amidation at the C‐terminus and acetylation at the N‐terminus for the 13C NMR was purchased from Genscript. NMR samples were prepared in 90%/10% H2O/D2O at varying calculated pH and constant ionic strength 1.0 M adjusted with KOH/KCl.32 Samples were prepared using KOH (with a constant ionic strength of 1.0 M using pK w = 14.16) and confirmed with a pH meter suitable for high pH measurements.35 Arginine concentrations for the 1H NMR titrations were 0.5 and 50 mM for the 13C natural abundance titrations. All NMR spectra were obtained on Bruker Avance 600 and 500 MHz NMR instruments equipped with 5‐mm QXI and 5‐mm TBI probes, respectively, for the 1H titrations and a 10‐mm BBO probe for the 13C natural abundance titrations. Spectra were recorded at 25°C using a 1D presaturation 1H NMR pulse sequence. 1H chemical shifts were referenced to internal 4,4‐dimethyl‐4‐silapentane 1‐sulfonic acid (DSS) at low pH and then the 1Hα chemical shift at high pH, as DSS showed inconsistencies at extreme pH. 13C natural abundance spectra were recorded using inverse‐gated 1H decoupling using a 45° flip angle. 13C chemical shifts were referenced to a CDCl3 capillary. At high pH > 11, degradation was observed at the C‐terminal end of the protected arginine variants; spectra were obtained immediately after sample preparation, and data from the degraded products were not used.

Because of incomplete titration curves even at pH > 14, chemical shifts of protonated and unprotonated species of the arginine variants and imidazole control were calculated from Spartan 10 using a Hartree‐Fock 6‐31G* basis set. Electrostatic potential maps, hydrophobicity, and volume were also calculated using Spartan 10 and Hartree‐Fock 6‐31G*. Methylated and control arginine variants for the calculations were shortened at the α/β carbons to focus on the ionizable side chains. Each variant and tautomer was made and individually minimized prior to calculation. The lowest energy tautomer, where applicable, was reported.

Supporting information

Supporting Information Figure 1.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Diem Tran and Brandon Cannup for synthesizing and providing the arginine variants.

References

- 1. Bartlett GJ, Porter CT, Borkakoti N, Thornton JM (2002) Analysis of catalytic residues in enzyme active sites. J Mol Biol 324:105–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kim J, Mao J, Gunner MR (2005) Are acidic and basic groups in buried proteins predicted to be ionized? J Mol Biol 348:1283–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bogan AA, Thorn KS (1998) Anatomy of hot spots in protein interfaces. J Mol Biol 280:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Li L, Vorobyov I, MacKerell AD, Allen TW (2008) Is arginine charged in a membrane? Biophys J 94:L11–L13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Harms MJ, Schlessman JL, Sue GR, Garcia‐Moreno B (2011) Arginine residues at internal positions in a protein are always charged. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:18954–18959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yoo J, Cui Q (2008) Does arginine remain protonated in the lipid membrane? Insights from microscopic pK(a) calculations. Biophys J 94:L61–L63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bedford MT, Clarke SG (2009) Protein arginine methylation in mammals: who, what, and why. Mol Cell 33:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boffa LC, Karn J, Vidali G, Allfrey VG (1977) Distribution of NG, NG,‐dimethylarginine in nuclear protein fractions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 74:969–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yang Y, Bedford MT (2013) Protein arginine methyltransferases and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 13:37–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Luscombe NM, Laskowski RA, Thornton JM (2001) Amino acid–base interactions: a three‐dimensional analysis of protein–DNA interactions at an atomic level. Nucleic Acids Res 29:2860–2874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hughes RM, Waters ML (2006) Arginine methylation in a β‐hairpin peptide: implications for Arg‐π interactions, deltaCp(o), and the cold denatured state. J Am Chem Soc 128:12735–12742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tripsianes K, Madl T, Machyna M, Fessas D, Englbrecht C, Fischer U, Neugebauer KM, Sattler M (2011) Structural basis for dimethylarginine recognition by the Tudor domains of human SMN and SPF30 proteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol 18:1414–1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Boisvert FM, Dery U, Masson JY, Richard S (2005) Arginine methylation of MRE11 by PRMT1 is required for DNA damage checkpoint control. Genes Dev 19:671–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. El‐Andaloussi N, Valovka T, Toueille M, Hassa PO, Gehrig P, Covic M, Hubscher U, Hottiger MO (2007) Methylation of DNA polymerase‐β by protein arginine methyltransferase 1 regulates its binding to proliferating cell nuclear antigen. FASEB J 21:26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. El‐Andaloussi N, Valovka T, Toueille M, Steinacher R, Focke F, Gehrig P, Covic M, Hassa PO, Schar P, Hubscher U, Hottiger MO (2006) Arginine methylation regulates DNA polymerase‐β. Mol Cell 22:51–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Harms MJ, Castaneda CA, Schlessman JL, Sue GR, Isom DG, Cannon BR, Garcia‐Moreno EB (2009) The pK(a) values of acidic and basic residues buried at the same internal location in a protein are governed by different factors. J Mol Biol 389:34–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Isom DG, Castaneda CA, Cannon BR, Garcia‐Moreno B (2011) Large shifts in pK a values of lysine residues buried inside a protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:5260–5265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Birch TW, Harris LJ (1930) A redetermination of the titration dissociation constants of arginine and histidine with a demonstration of the zwitterion constitution of these molecules. Biochem J 24:564–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schmidt CLA, Kirk PL, Appleman WK (1930) The apparent dissociation constants of arginine and of lysine and the apparent heats of ionization of certain amino acids. J Biol Chem 88:285–293. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hunter A, Borsook H (1924) The dissociation constants of arginine. Biochem J 18:883–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Albert A (1950) Quantitative studies of the avidity of naturally occurring substances for trace metals; amino‐acids having only two ionizing groups. Biochem J 47:531–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Clarke ER, Martell AE (1970) Metal chelates of arginine and related ligands. J Inorg Nucl Chem 32:911–926. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Noszal B, Kassai‐Tanczos R (1991) Microscopic acid–base equilibria of arginine. Talanta 38:1439–1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fitch CA, Platzer G, Okon M, Garcia‐Moreno EB, McIntosh LP (2015) Arginine: its pK a value revisited. Protein Sci 24:752–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nagai H, Kuwabara K, Carta G (2008) Temperature dependence of the dissociation constants of several amino acids. J Chem Eng Data 53:619–627. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wood EJ (1987) Data for biochemical research (third edition) by RMC Dawson, DC Elliott, WH Elliott, KM Jones, pp 580. Oxford Science Publications, OUP, Oxford, 1986. ISBN 0‐19‐855358‐7. Biochem Educ 15:97. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Orgovan G, Noszal B (2011) The complete microspeciation of arginine and citrulline. J Pharm Biomed Anal 54:965–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Greenstein JP (1933) Studies of the peptides of trivalent amino acids. III. The apparent dissociation constants, free energy changes, and heats of ionization of peptides involving arginine, histidine, lysine, tyrosine, and aspartic and glutamic acids, and the behavior of lysine peptides toward nitrous acid. J Biol Chem 101:603–621. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Melville J, Richardson GM (1935) The titration constants of some amides and dipeptides in relation to alcohol and formaldehyde titrations of amino‐N. Biochem J 29:187–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nair MS, Regupathy S (2009) Studies on Cu(II)‐mixed ligand complexes containing a sulfa drug and some enzyme constituents. J Coord Chem 63:361–372. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ballinger P, Long FA (1959) Acid ionization constants of alcohols. I. Trifluoroethanol in the solvents H2O and D2O1 . J Am Chem Soc 81:1050–1053. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Popov K, Rönkkömäki H, Lajunen LHJ (2006) Guidelines for NMR measurements for determination of high and low pK a values (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl Chem 78:663–675. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Szakacs Z, Kraszni M, Noszal B (2004) Determination of microscopic acid–base parameters from NMR–pH titrations. Anal Bioanal Chem 378:1428–1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Andre I, Linse S, Mulder FA (2007) Residue‐specific pK a determination of lysine and arginine side chains by indirect 15N and 13C NMR spectroscopy: application to apo‐calmodulin. J Am Chem Soc 129:15805–15813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kron I, Marshall SL, May PM, Hefter G, Königsberger E (1995) The ionic product of water in highly concentrated aqueous electrolyte solutions. Monatsh Chem 126:819–837. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Walba H, Isensee RW (1961) Acidity constants of some arylimidazoles and their cations. J Organ Chem 26:2789–2791. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sikorsky T, Hobor F, Krizanova E, Pasulka J, Kubicek K, Stefl R (2012) Recognition of asymmetrically dimethylated arginine by TDRD3. Nucleic Acids Res. 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nguyen LT, de Boer L, Zaat SA, Vogel HJ (2011) Investigating the cationic side chains of the antimicrobial peptide tritrpticin: hydrogen bonding properties govern its membrane‐disruptive activities. Biochim Biophys Acta 1808:2297–2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bonucci A, Balducci E, Martinelli M, Pogni R (2014) Human neutrophil peptide 1 variants bearing arginine modified cationic side chains: effects on membrane partitioning. Biophys Chem 190/191:32–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Angyal SJ, Warburton WK (1951) The basic strengths of methylated guanidines. J Chem Soc (Resumed) 549:2492–2494. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhang M, Vogel HJ (1993) Determination of the side chain pK a values of the lysine residues in calmodulin. J Biol Chem 268:22420–22428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Livesay DR, Jacobs DJ, Kanjanapangka J, Chea E, Cortez H, Garcia J, Kidd P, Marquez MP, Pande S, Yang D (2006) Elucidating the conformational dependence of calculated pK a values. J Chem Theory Comput 2:927–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mangold M, Rolland L, Costanzo F, Sprik M, Sulpizi M, Blumberger J (2011) Absolute pK a values and solvation structure of amino acids from density functional based molecular dynamics simulation. J Chem Theory Comput 7:1951–1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Derbel N, Clarot I, Mourer M, Regnouf‐de‐Vains JB, Ruiz‐Lopez MF (2012) Intramolecular interactions versus hydration effects on p‐guanidinoethyl‐phenol structure and pK a values. J Phys Chem A 116:9404–9411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Griffiths MZ, Alkorta I, Popelier PLA (2013) Predicting pK a values in aqueous solution for the guanidine functional group from gas phase ab initio bond lengths. Mol Inform 32:363–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lee D, Lee J, Seok C (2013) What stabilizes close arginine pairing in proteins? Phys Chem Chem Phys 15:5844–5853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Liu K, Chen C, Guo Y, Lam R, Bian C, Xu C, Zhao DY, Jin J, MacKenzie F, Pawson T, Min J (2010) Structural basis for recognition of arginine methylated Piwi proteins by the extended Tudor domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:18398–18403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Liu K, Guo Y, Liu H, Bian C, Lam R, Liu Y, Mackenzie F, Rojas LA, Reinberg D, Bedford MT, Xu RM, Min J (2012) Crystal structure of TDRD3 and methyl–arginine binding characterization of TDRD3, SMN and SPF30. PLoS One 7:e30375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information Figure 1.