Abstract

Background:

Poor nutrition habits in adolescent girls endanger their health and are followed by serious systemic diseases in adulthood and negative effects on their reproductive health. To design health promotion programs, understanding of the intra- and interpersonal associated factors with treatment is essential, and this was the aim of this study.

Materials and Methods:

This cross-sectional study was conducted on 193 adolescent girls of age 11-15 years. Random cluster selection was used for sample selection. Food group consumption pattern was assessed by food frequency questionnaire. Also, perceived susceptibility/severity and nutritional attitude as intrapersonal factors and social support as interpersonal factor were assessed. The relationship between food group consumption level and nutritional attitude and perceived treat (susceptibility/severity) as intrapersonal factors and perceived social support as interpersonal factor were assessed by linear multiple regression and analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Results:

Results showed that the level of sweetmeat food consumption was related to perceived social support (P = 0.03) and nutritional attitude (P = 0.01) negatively. In addition, an inverse and significant association was found between the level of junk food intake and informational perceived social support (P = 0.004). The association between the level of fast food intake and the perceived parental social support for preparation of healthy food was negatively significant (P = 0.03). Breakfast consumption was related to nutritional attitude (P = 0.03), social support (P = 0.03), and perceived severity (P = 0.045).

Conclusions:

Results revealed that perceived social support and nutritional attitude are the important and related factors in dietary intake among girls, and promotion of social support and modification of nutritional attitude may lead to healthy nutritional behaviors among them.

Keywords: Adolescent, attitude, food intake, girls, nutritional attitude, perceived social support, perceived threat, severity, susceptibility

INTRODUCTION

Adolescence is a critical period in the life cycle of human beings. Growth and development of young people in this period is dependent on getting adequate healthy food. Many of the adolescents’ eating habits may have severe consequences in the long run. Imbalance in food intake and inappropriate eating behavior during adolescence are known to be the predisposing factors for decreased learning ability and academic achievement,[1] outbreak of serious systemic diseases such as hyperlipidemia,[2] arthrosclerosis,[3] diabetes mellitus,[4,5] some types of cancer,[6,7] and osteoporosis[8] among adults, while good nutrition pattern improves the metabolic functions and mental health among adolescents.[9,10] Poor nutritional patterns such as skipping breakfast, inappropriate calorie intake, and consumption of salty and fat-rich foods result in obesity,[11,12] decreasing learning ability in adolescents,[13] and increased risk for systemic diseases in the later stages of life.[2,3,4,5] The nutritional status is more important in women. The systemic and metabolic conditions caused due to the poor nutrition have adverse effects on maternal and fetal health during pregnancy,[14,15,16] and may negatively affect the health of the next generation.

Although the correction of nutritional as well as other aspects of lifestyle ensures women's good health, the public health authorities’ efforts to improve the nutrition of girls are not successful. Inadequate intake of calcium-rich foods[17] and low intake of essential vitamins among Iranian teenage girls[18,19,20] are cases that indicate the need for a change in the feeding behavior among Iranian girls.

Although inadequate knowledge is associated with lowered motivation for accomplishment of health promotion related behavior in the modern structure of the present society, provision of health services that can promote health-related behaviors, in addition to enhancement of knowledge, is of great importance. Therefore, one of the basic needs to design and provide appropriate strategies to promote health-related behavior is having a deep understanding of the psychological processes affecting the manifestation of behavior and function.[21] These processes are formed during adolescence period in many cases. Complexity of behavior among adolescents and the effects of various factors on their behavior require a deeper vision on their health-related behavior components. Therefore, in the present study, it was tried to assess the relationship between some of the psychological factors and adolescent girls’ nutritional patterns, so as to provide an appropriate framework for designing the health promotion programs through their detection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This cross-sectional study was conducted on 193 adolescent girls who were studying in guidance school in Isfahan, Iran, with a mean age of 11-15 years, from October 2014 to January 2015. The objective of this study was assessment of the relationship between the level of intake of food groups with nutritional attitude, familial social support, and perceived threat (perceived susceptibility and severity). The level of consumption from the food groups and fast foods (units/day, units/week) was assessed by a validated semi-quantitative 168 food items.[21] Also the frequency of having breakfast was accessed by one question. Depending on the portion size, the frequency of food intake was recorded in times per day, week, and month, or never. For all the main food items in the FFQ, the frequency per day was multiplied by the amount consumed, depending on the portion size, to compute the total amount consumed per day. A 14-item questionnaire was developed covering a review of the literature[21] and expert opinion determinants of perceived susceptibility/severity. Also, nutritional attitude was assessed by a 34-item questionnaire based on five-point Likert's scale (1-5), and the adolescents’ perceived familial social support was measured in three dimensions (informational, accessible, and encouragement) by a 14-item questionnaire.

A pilot study was conducted leading to the final revision. A psychometric evaluation of the later version generally revealed a good criterion-related validity and internal consistency. For assessment of the internal reliability of questionnaires, a pilot study leading to the final revision of the questionnaires was conducted. Cronbach's alpha for evaluation of the internal consistency was 0.82 for perceived susceptibility, 0.80 for perceived severity, 0.85 for nutritional attitude, and 0.88 for familial social support.

Sample statements are as follows: (1) Perceived susceptibility: Poor nutrition at any age increases the likelihood of disease; (2) perceived severity: Poor nutrition can lead to debilitating disease; (3) nutritional attitude: I feel healthy by eating nutritious meals; and (4) familial social support: How much do your parents make fruit and vegetables available? Random cluster selection was used for sample selection. Eligible adolescents were invited to participate in a baseline interview after being briefed on the study. All eligible subjects and their parents also signed a consent form. After data collection, status of having breakfast among subjects was categorized as never or rarely, sometimes, usually, and always.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 19 (Chicago, IL, USA). The results were reported as geometric mean and standard deviation. The data were analyzed using linear regression (adjusted for adolescents and adolescent age, employment status of their mothers, and monthly income of their family). In addition, the evaluated psychological factors were compared according to the status of having breakfast categorization by analysis of variance (ANOVA). The P value of less than 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Ethical considerations

The Institutional Review Board and the Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences approved the study.

RESULTS

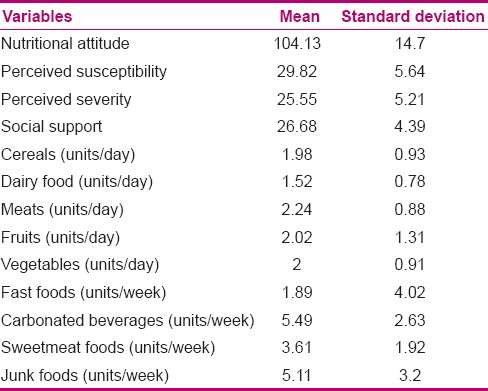

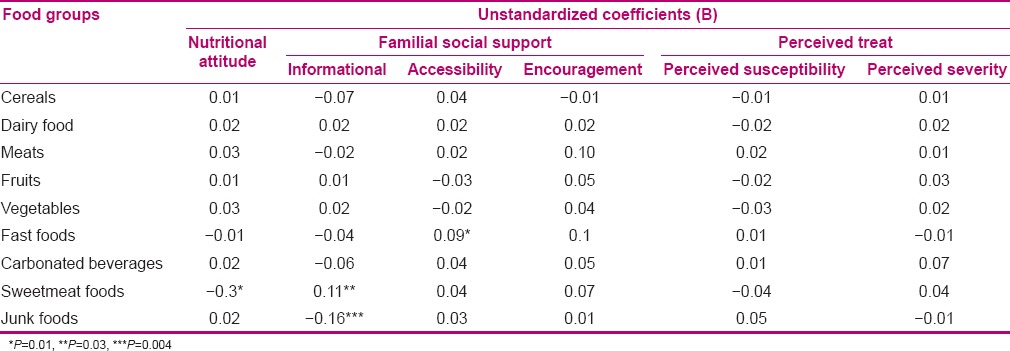

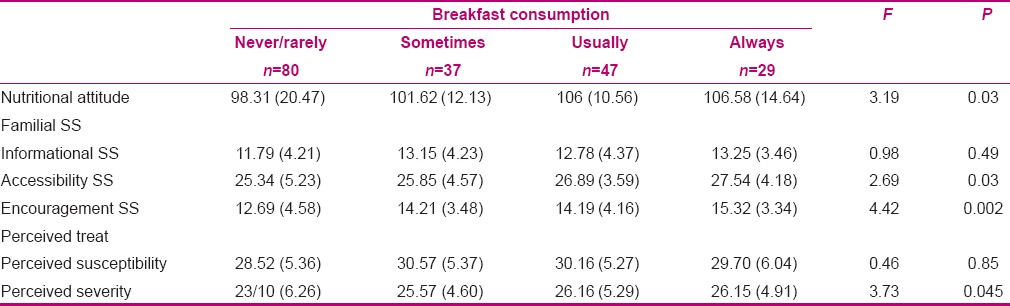

In total, 195 adolescents were selected and 193 adolescents completed the questionnaires. Mean (standard deviation) age of adolescents was 14.83 (1.89). Results showed that 71% (n = 137) of the mothers were employed and 29% (n = 56) were housewives. The mean (standard deviation) of the level of nutritional attitude, perceived susceptibility/severity, perceived familial social support, and the level of the food group consumption (units/day and units/week) have been presented in Table 1. The associations between the evaluated psychological factors and the food group consumption level have been shown in Table 2. The results showed that the level of sweetmeat consumption was negatively related to the level of the nutritional attitude and perceived familial social support in all dimensions. Using stepwise multivariable linear regression analysis it was found that among these factors, only accessibility (B = 0.93, P < 0.0001) and nutritional attitude (B = 0.73, P = 0.009) could significantly predict the level of sweetmeat consumption. The association between the level of junk food consumption and informational social support was negative and significant. The level of fast food consumption and perceived accessibility was negatively significant [Table 2]. Also, the level of sweetmeat consumption was related to monthly income (B = 0.58, P = 0.03). Also the breakfast consumption status was related to Nutritional attitude, Accessibility, Encouragement of parents and Perceived severity [Table 3].

Table 1.

Descriptive results of the variables

Table 2.

The association between food groups intake with nutritional attitude, perceived threat, and perceived social support

Table 3.

The comparison of nutritional attitude, perceived social support, and perceived threats in different groups based on breakfast consumption status

DISCUSSION

The present study aimed to investigate the association between some psychological factors and female adolescents’ food group consumption levels and revealed that positive attitude and familial social support are the most important determinants for food intake by adolescents. The results showed that although consumption of fast foods such as sausage, bologna etc., independent of economic status, is inversely associated with familial social support in provision of adolescents’ nutritional needs, the fast food consumption level is not associated with the perception of threat and nutritional attitude.

Consistent with these findings, there are reports on the existing association between the social support with health-related behaviors among the adolescents, which are in line with the present study. Some studies have reported that adolescents’ social support is associated with their screen-spent time on devices such as TV, computer, etc.[23,24,25]

There is also a proved association between the consumption level of junk foods such as carbonated soft drinks and the screen time based sedentary behavior.[26] A literature review showed an association between the number of family meal serves and eating disorders in adolescents.[27] Consumption of main food and snacks provides an appropriate time to make food habits in adolescents. On the contrary, low social support leads to incidence of mental disorders such as depression and an increase in the behaviors toward higher junk food consumption.[28] Although the results showed that the children of the parents who try to provide healthy foods more had a healthier nutrition, lack of a correlation between the encouragement and informational social support and the amount of healthy food consumption showed that parents’ effort to provide their adolescents with information, to encourage them to take nutrient foods, and to avoid unhealthy foods was not effective on their intake of ready meals.

Therefore, it is likely that after adolescents’ dependence on families’ provision of healthy foods disappears and when they enter the teenage period and adulthood, their nutritional pattern may change under new conditions. In conditions of independency for food provision, adolescents’ interpersonal factors such as their attitude[29] and understanding of the threat[30] may act as more important determinants for selection of their favorite food.

Our obtained results showed an inverse association between adolescents’ level of sweets intake and social support perception in provision of appropriate nutritional facilities, and their encouragement for improvement of nutritional behavior as well as their attitude toward nutrition. These findings show that familial social support is followed by modification of adolescents’ sweets consumption through its effect on adolescents’ nutritional attitude. On the other hand, another obtained result was on association between adolescents’ breakfast consumption pattern and their attitude toward nutrition. Breakfast is a major and important food portion that prevents the false appetite to consume sweets through regulating metabolic conditions of the body,[31] in addition to provision of physical and mental power to do daily activities.[13] Therefore, factors such as familial social support in increased access of adolescents to healthy foods may be accompanied with the behavior of regular breakfast consumption and prevents the false appetite for sweets. Another finding showed a significant inverse association between the amount of unhealthy nuts intake and informational social support. Consumption of potato chips and crunches is counted as a poor food habit among children and adolescents, and in addition to causing a false feeling of being sated and reduction of desire to take essential food groups, it results in prehypertension at older ages due to obesity and receiving high amounts of salt.[32] Consumption of such foods usually is in the form of a recreational snack, but not the main food portion. Therefore, the most effective factor in prevention of adolescents’ consumption of these foods is their awareness of the harmful effects of such foods and the importance of healthy nutrition in preservation of health. Awareness is achieved in a background in which the possibility of obtaining useful information, despite existing vast mass media propaganda is provided. The present study confirmed that parents’ social support can reduce consumption of these harmful foods through making a background to receive helpful nutritional information.

Meanwhile, research showed that familial social support and attitude toward nutrition is accompanied with a reduction in consumption of harmful foods. There was no significant association observed between psychological behavioral factors and intake of essential nutrient groups of corns, meat, vegetables, fruits, and diary. The observed association was between social support and nutritional attitude and avoiding consumption of the foods impairing adolescents’ health. Lack of any association between these factors and intake of essential nutrient groups showed that the observed psychological factors were more of a predisposing factor for the incidence of inappropriate nutritional behavior and the fact that amount of essential nutrient group consumption level was more dependent on other factors, compared to these factors. Consideration of adolescents’ dependency on the family nutritional pattern to consume essential nutrient groups can be a proper explanation for this finding. The results also showed that understanding of the threat, resulting from an inappropriate nutrition, is not a determinant for having an appropriate nutritional pattern. Liou et al. reported that among the structures related to health belief model, the perceived barriers and self-efficacy were the only predicting factors for nutritional behavior among Asian adults residing in USA.[30] Consistent with the results of the present study, their results showed that besides existing barriers such as lack of social support in access to beneficial nutrients and adequate information to attain enough knowledge about healthy nutrition, understanding the threat, resulting from inappropriate nutrition, has no effect on nutritional behavior. The relationship between nutritional attitude and mothers’ educational level, in addition to the lack of relationship between psychological factors with the economic status and fathers’ educational level indicated the mothers’ key role in providing appropriate nutritional motivation among the adolescents and improvement of their nutritional conditions.

A study conducted on European adolescents showed that fathers’ and mothers’ education levels both were effective on adolescents’ nutrition quality.[33] Meanwhile, in the present study, there was no significant association between fathers’ education and adolescents’ nutritional behavior. In societies such as Iran, management of family nutrition is handled more by the mothers, compared to that in European countries, which can be a reason for this result obtained. The association between mothers’ education level and their adolescents’ nutritional status has been already reported.[34] Although in the present study mothers’ level of knowledge was not assessed, nutritional knowledge and selection of healthy foods is dependent on education level.[35] Therefore, mothers with higher education support their children concerning their health preservation and utilize existing resources in the family to make healthy and nutrient foods more than others.

CONCLUSION

The present study showed that social support and the attitude toward nutrition, excluding the family economic status, are among the important and efficient factors in female adolescents’ nutritional behavior and the mothers with higher education provide these for their children more than others do. Therefore, public health interventions to promote familial social support may be an effective strategy for improving the nutritional status among adolescent girls.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nursing and Midwifery Care Research Center (GN: 293139).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Nursing and Midwifery Care Research Center for funding the survey.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shi X, Tubb L, Fingers ST, Chen S, Caffrey JL. Associations of physical activity and dietary behaviors with children's health and academic problems. J Sch Health. 2013;83:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2012.00740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inci M, Demirtas A, Sarli B, Akinsal E, Baydilli N. Association between body mass index, lipid profiles, and types of urinary stones. Ren Fail. 2012;34:1140–3. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2012.713298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson JA, Regnault TR. In utero origins of adult insulin resistance and vascular dysfunction. Semin Reprod Med. 2011;29:211–24. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1275522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanada H, Yokokawa H, Yoneda M, Yatabe J, Sasaki Yatabe M, Williams SM, et al. High body mass index is an important risk factor for the development of type 2 diabetes. Intern Med. 2012;51:1821–6. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.7410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kriska A, Delahanty L, Edelstein S, Amodei N, Chadwick J, Copeland K, et al. Sedentary behavior and physical activity in youth with recent onset of type 2 diabetes. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e850–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma Y, Yang Y, Wang F, Zhang P, Shi C, Zou Y, et al. Obesity and risk of colorectal cancer: A systematic review of prospective studies. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53916. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao ZG, Guo XG, Ba CX, Wang W, Yang YY, Wang J, et al. Overweight, obesity and thyroid cancer risk: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Int Med Res. 2012;40:2041–50. doi: 10.1177/030006051204000601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Junior IF, Cardoso JR, Christofaro DG, Codogno JS, de Moraes AC, Fernandes RA. The relationship between visceral fat thickness and bone mineral density in sedentary obese children and adolescents. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-13-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dipnall JF, Pasco JA, Meyer D, Berk M, Williams LJ, Dodd S, et al. The association between dietary patterns, diabetes and depression. J Affect Disord. 2015;174:215–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mooreville M, Shomaker LB, Reina SA, Hannallah LM, Adelyn Cohen L, Courville AB, et al. Depressive symptoms and observed eating in youth. Appetite. 2014;75:141–9. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nurul-Fadhilah A, Teo PS, Huybrechts I, Foo LH. Infrequent breakfast consumption is associated with higher body adiposity and abdominal obesity in Malaysian school-aged adolescents. PLoS One. 2013;8:e59297. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Powell LM, Nguyen BT, Dietz WH. Energy and nutrient intake from pizza in the United States. Pediatrics. 2015;135:322–30. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Defeyter MA, Russo R. The effect of breakfast cereal consumption on adolescents’ cognitive performance and mood. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:789. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marchi J, Berg M, Dencker A, Olander EK, Begley C. Risks associated with obesity in pregnancy, for the mother and baby: A systematic review of reviews. Obes Rev. 2015;16:621–38. doi: 10.1111/obr.12288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duong V, Davis B, Falhammar H. Pregnancy and neonatal outcomes in Indigenous Australians with diabetes in pregnancy. World J Diabetes. 2015;6:880–8. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v6.i6.880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCance DR. Diabetes in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;29:685–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2015.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montazerifar F, Karajibani M, Dashipour AR. Evaluation of dietary intake and food patterns of adolescent girls in Sistan and Baluchistan province, Iran. Funct Food Health Dis. 2012;2:62–71. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mirmiran P, Golzarand M, Serra-Majem L, Azizi F. Iron, Iodine and vitamin A in the Middle East; a systematic review of deficiency and food fortification. Iran J Public Health. 2012;41:8–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Azadbakht L, Esmaillzadeh A. Macro and micro-nutrients intake, food groups consumption and dietary habits among female students in Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2012;14:204–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hovsepian S, Amini M, Aminorroaya A, Amini P, Iraj B. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among adult population of Isfahan City, Iran. J Health Popul Nutr. 2011;29:149–55. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v29i2.7857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Models of Individual Health Behavior. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. 4th ed. San Fransisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mirmiran P, Esfahani FH, Mehrabi Y, Hedayati M, Azizi F. Reliability and relative validity of an FFQ for nutrients in the Tehran lipid and glucose study. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13:654–62. doi: 10.1017/S1368980009991698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lown DA, Braunschweig CL. Determinants of physical activity in low-income, overweight African American girls. Am J Health Behav. 2008;32:253–9. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2008.32.3.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cummings HM, Vandewater EA. Relation of adolescent video game play to time spent in other activities. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:684–9. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.7.684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Springer AE, Kelder SH, Hoelscher DM. Social support, physical activity and sedentary behavior among 6 th -grade girls: A cross-sectional study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2006;3:8. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-3-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Falbe J, Willett WC, Rosner B, Gortmaker SL, Sonneville KR, Field AE. Longitudinal relations of television, electronic games, and digital versatile discs with changes in diet in adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100:1173–81. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.088500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harrison ME, Norris ML, Obeid N, Fu M, Weinstangel H, Sampson M. Systematic review of the effects of family meal frequency on psychosocial outcomes in youth. Can Fam Physician. 2015;61:e96–106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Costigan SA, Barnett L, Plotnikoff RC, Lubans DR. The health indicators associated with screen-based sedentary behavior among adolescent girls: A systematic review. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:382–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dowd AJ, Chen MY, Jung ME, Beauchamp MR. “Go Girls!”: Psychological and behavioral outcomes associated with a group-based healthy lifestyle program for adolescent girls. Transl Behav Med. 2015;5:77–86. doi: 10.1007/s13142-014-0285-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liou D, Bauer K, Bai Y. Investigating obesity risk-reduction behaviours and psychosocial factors in Chinese Americans. Perspect Public Health. 2014;134:321–30. doi: 10.1177/1757913913486874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peronnet F, Meynier A, Sauvinet V, Normand S, Bourdon E, Mignault D, et al. Plasma glucose kinetics and response of insulin and GIP following a cereal breakfast in female subjects: Effect of starch digestibility. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69:740–5. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2015.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi L, Krupp D, Remer T. Salt, fruit and vegetable consumption and blood pressure development: A longitudinal investigation in healthy children. Br J Nutr. 2014;111:662–71. doi: 10.1017/S0007114513002961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beghin L, Dauchet L, De Vriendt T, Cuenca-García M, Manios Y, Toti E, et al. HELENA Study Group Influence of parental socio-economic status on diet quality of European adolescents: Results from the HELENA study. Br J Nutr. 2014;111:1303–12. doi: 10.1017/S0007114513003796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ren YJ, Liu QM, Cao CJ, Lü J, Li LM. Fruit and vegetable consumption and related influencing factors among urban junior students in Hangzhou. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2013;34:236–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKinnon L, Giskes K, Turrell G. The contribution of three components of nutrition knowledge to socio-economic differences in food purchasing choices. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17:1814–24. doi: 10.1017/S1368980013002036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]