To get to Gunbalanya in Australia’s Northern Territory, you have to go in the dry season, drive east from Darwin and cross the East Alligator River—wrongly named for the crocodiles that are so impressive in both size and number. Gunbalanya is a “large” Aboriginal town of about 1 200 people in West Arnhem Land; and is one of 29 remote indigenous communities across Australia where there is a local development plan in which the local indigenous community is heavily involved.1

The need is great. In 2010 to 2012, life expectancy for Aboriginals in the Northern Territory was 63.4 years for men and 68.7 years for women—14.4 years shorter than it was for the nonindigenous population.2 In the Northern Territory, the Aboriginal population is 30% of the whole and 83% of the prison population. Australia ranks second on the United Nation’s Development Program’s Human Development Index—a measure that includes literacy, life expectancy, and gross domestic product. If Australia’s indigenous population were considered as a separate country, they would rank 122.

Does any of this sound familiar to US readers, considering America’s indigenous population? Or, the dramatic socioeconomic inequalities within US cities—the 20-year gap in male life expectancy between rich and poor areas in Baltimore, Maryland, for example? In Australia, as elsewhere, central government policy is important—although the situation was not eased by an Australian Prime Minister referring to living in these deprived communities as a lifestyle choice. But national solutions to these gross inequalities between indigenous and nonindigenous populations have failed, consistently and repeatedly. Local action involving empowerment of communities is likely to be crucial.3

Australian Aborigines, at first blush, may seem like an extreme example of health inequities, but they are at the end of a spectrum of disadvantage, not on a different spectrum. Note, in moving from Australia to Baltimore, I seem to have conflated inequalities between ethnic groups with socioeconomic inequalities. In my judgment, most racial/ethnic inequalities in health can be attributed to social determinants of health, as can socioeconomic inequalities. To see that, look at the medical conditions that lead to dramatic shortening of lives among Australian Aborigines. It is not infant mortality. At 9.6 per 1000 live births, though higher than the Australian average of 4.3, it does not suggest third-world poverty. The diseases leading to a greater than 14 year gap in life expectancy are heart disease, cancer, respiratory disease, and diabetes, as well as accidents and violence. The same diseases show a socioeconomic gradient in rich countries: the lower the social position, the higher the risk.

Gunbalanya, Aboriginal town of about 1200 people in West Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory of Australia. Photo courtesy of Michael Marmot; printed with permission.

Given that the causes of disease and violence are likely to be the same wherever we find them, it follows that the remedies should be similar. In Fair Society Healthy Lives,4 the report of my review of health inequalities in England (the English Marmot Review), we emphasized six areas both as explanations of the social gradient and solutions: early child development, education and lifelong learning, employment and working conditions, minimum income for healthy living, healthy and sustainable communities, and social determinants approach to prevention.

Basic to these are inequities in power, money, and resources.

The causes of extreme health disadvantage are not different in kind in indigenous communities or inner city ghettos, but in degree, from those with less extreme deprivation. Wherever we look, we find that health follows a social gradient. In England, for example, when neighborhoods are classified by degrees of deprivation, we do indeed find that the most deprived areas do have the shortest life expectancy and shortest disability-free life expectancy. But more than that, the graded relation between deprivation and health runs all the way from top to bottom of society. The gradient implies that we should not only focus on the most deprived areas, but be striving to improve the whole of society. We coined the phrase proportional universalism to convey that Universalist policies are those most likely to create inclusive societies, but effort should be proportional to need. People lower in the social hierarchy are likely to require greater effort to bring them into the mainstream.

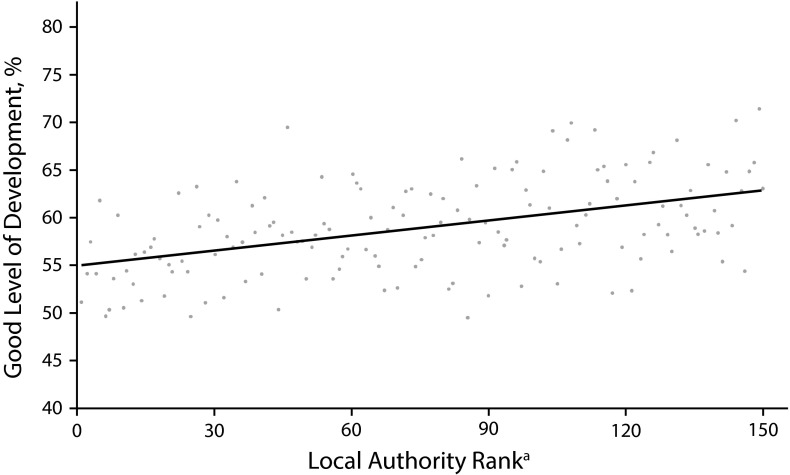

The question then is where interventions should take place: global, national, local. Figure 1 illustrates this issue. It plots the percentage of children aged five years achieving a good level of development for each local authority in England. The figure suggests two levels of interventions. First, it shows that the more deprived the local area, the smaller the percentage of children aged five years who achieve a good level of development. One intervention, then, is to reduce deprivation. International comparisons show clearly that fiscal policy, along with taxes and benefits, can reduce child poverty dramatically. In Sweden, for example, the percentage of children in poverty (< 60% of the median income) is reduced from 32% to just more than 12% through taxes and transfers. The United States is a laggard. National policy could reduce child poverty, but in the United States, it is not being done to anything like the extent of other Organisation For Economic Co-operation Develpoment countries. In the United Kingdom, from 2010 to 2013, the proportion of households with children below an acceptable minimum income threshold rose from 31% to 39%.

FIGURE 1—

Children Achieving a Good Level of Development at Age 5 Years by Local Authority Rank: England, 2011

Source. Adapted from Marmot.3

aThe local authority rank is based on the Index of Multiple Deprivation (high rank implies less deprivation).

Figure 1 suggests a second strategy. There is scatter around the regression line. For a given level of deprivation, some communities are doing better than others. Interventions to help families, effort proportional to need, can make a difference to early child development.

It should not be either/or; policies need to be national and local. For example, in Sweden, there had been some reluctance on the part of national government to set up a cross-government mechanism to achieve health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Action happened at the local level, starting with the Swedish city of Malmo, which set up a city commission for a socially sustainable Malmo. Linkoping and Norrkoping, Gothenburg and Ostersund all have city level mechanisms for achieving health equity. Now, the national government has followed by setting up a national commission.

The argument for early child development can be extended to all six of my domains that are mentioned above. National governments can play an enabling role, but action at the community level is essential. Central to action on social determinants of health is empowerment of individuals and communities. It will take concerted action at the community level.

REFERENCES

- 1. Australian Government Department of Social Services. Local implementation plans, Gunbalanya 2013. 2014. Available at: http://www.dss.gov.au/our-responsibilities/indigenous-australians/publications-articles/communities-regions/local-implementation-plans/local-implementation-plans-gunbalanya?HTML. Accessed December 15, 2015.

- 2.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Life tables for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians 2010-2012. (cat. no. 3302.0.55.003 2013). 2014. Available at: http://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/Ausstats/subscriber.nsf/0/BD51C922BFB7C6C1CA257C230011C97F/$File/3302055003_2010-2012.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2015.

- 3.Marmot M. The Health Gap: The Challenge of an Unequal World. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Publishing; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marmot M. Fair Society, Healthy Lives: The Marmot Review; Strategic Review of Health Inequalities in England Post-2010. London, UK: The Marmot Review Team; 2010. [Google Scholar]