Abstract

Objectives. We sought to better understand tuberculosis (TB) epidemiology among New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) residents, after a recent TB investigation identified patients who had the same TB strain.

Methods. The study population included all New York City patients with TB confirmed during 2001 through 2009. Patient address at diagnosis determined NYCHA residence. We calculated TB incidence, reviewed TB strain data, and identified factors associated with TB clustering.

Results. During 2001 to 2009, of 8953 individuals in New York City with TB, 512 (6%) had a NYCHA address. Among the US-born, TB incidence among NYCHA residents (6.0/100 000 persons) was twice that among non-NYCHA residents (3.0/100 000 persons). Patients in NYCHA had high TB strain diversity. US birth, younger age, and substance use were associated with TB clustering among NYCHA individuals with TB.

Conclusions. High TB strain diversity among residents of NYCHA with TB does not suggest transmission among residents. These findings illustrate that NYCHA’s higher TB incidence is likely attributable to its higher concentration of individuals with known TB risk factors.

Although tuberculosis (TB) rates in the United States have declined since the TB epidemic peaked in 1992,1 TB continues to disproportionately affect the poor,2,3 racial and ethnic minorities,2,4 substance users,5 and other marginalized populations.2,3,5,6 In New York City, despite a sharp decline in TB incidence since 1992 (1992 incidence = 51.1 cases per 100 000 population),1 the TB incidence rate in 2013 was more than twice the US average (8.0 vs 3.0 per 100 000 population)7,8 and disparities persist. In 2013, the incidence rate of TB in New York City among non-Hispanic Blacks was more than 5 times that among non-Hispanic Whites.7 Furthermore, area-based poverty indicators revealed that 53% of individuals diagnosed with TB in 2012 resided in high- or very-high-poverty areas within New York City.9

During a TB epidemiological investigation, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) Bureau of Tuberculosis Control staff identified individuals with TB who lived in New York City public housing developments and had the same strain of TB. New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) is the largest public housing authority in North America, housing more than 400 000 low- to moderate-income New Yorkers.10 Among NYCHA residents, 46% are non-Hispanic Black, 45% are Hispanic, 5% are Asian, and 4% are White; 79% of heads of households are US-born; and the average residency is 20 years.11 The epidemiological investigation prompted the DOHMH to systematically investigate the epidemiology of TB among New York City public housing residents.

The study objectives were to

quantify the number of patients with TB who reported a NYCHA residence at time of TB diagnosis;

estimate TB incidence rates among persons living in NYCHA developments;

compare demographic, clinical, and social characteristics of persons with TB who are NYCHA and non-NYCHA residents;

describe the molecular epidemiology of TB stratified by NYCHA residence; and

identify patient factors associated with TB strain clustering among NYCHA and non-NYCHA residents.

METHODS

The study population included all New York City patients with TB verified from January 1, 2001, through December 31, 2009. We obtained patient demographic, clinical, and social history information from the New York City TB surveillance registry.

We used patient address at TB diagnosis to identify NYCHA residence. We geocoded and assigned addresses building identification numbers through the New York City DOHMH Geographic Information Systems Center’s online geocoder. We matched individual patient building identification numbers to an array of NYCHA building identification numbers provided by NYCHA staff. Individuals whose address building identification number matched a NYCHA building identification number were identified as having a NYCHA residence at diagnosis. We defined addresses that did not match a NYCHA building identification number or that were unable to be geocoded (n = 87; < 1% including addresses outside of New York City) as non-NYCHA residences.

We used annual NYCHA population counts for each year of the study period to calculate TB incidence rates among persons residing in NYCHA developments. We used unchallenged US Census Bureau estimates of New York City population totals for each study year to calculate overall New York City TB incidence by study year.12,13 To estimate the TB incidence rate among US-born NYCHA residents, we used the 2002, 2005, and 2008 editions of the US Census Bureau New York City Housing and Vacancy Survey to approximate the proportion of US-born New York City public housing heads of households. For incidence calculations among US-born NYCHA residents, we used the proportion of US-born heads of households in 2002 (79%; obtained from the 2002 survey,14 the median value of the 3 surveys) to estimate the proportion of NYCHA residents that were US-born. We used the proportion of US-born New York City residents from the 2000 Census (64%) as a proxy for the proportion of US-born non-NYCHA residents for each study year.

We used sociogeographic exposure indices to adjust for individual-level exposures relevant to TB epidemiology in our analyses, as outlined by Acevedo-Garcia.2-3 Individual-level exposures were not available; therefore, we used census-tract exposures by race as a surrogate. We calculated 5 sociogeographic exposure indices by using 2000 Census data: poverty (proportion of persons living below the poverty line), residential racial segregation (proportion of persons having the same race as one’s own race in one’s neighborhood), residential racial concentration (density of persons having the same race as one’s own race in one’s neighborhood), severe overcrowding (proportion of units with mean persons per room more than 1.5 in one’s neighborhood), and local foreign-born population (proportion of foreign-born persons in one’s neighborhood). For each exposure, we established thresholds to define high or low exposure. We adopted the thresholds from established literature for poverty2,15-17 and residential racial segregation,2,18–20 and from census data for residential racial concentration, severe overcrowding, and local foreign-born population (we set these 3 threshold values as one third higher than the overall New York City value). We coded values greater than the threshold value as high exposure to the corresponding sociogeographic exposure index. Conversely, we defined values less than or equal to the threshold value as low exposure. Extreme exposure to these measures was a separate characteristic defined as having high exposure in at least 4 of the 5 sociogeographic exposure indices.

We calculated values for each sociogeographic exposure index for 8 race categories in each of the 176 New York City zip codes(Appendix A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Race categorization was consistent between US Census 2000 and New York City TB surveillance data. We aggregated census tract–level data into zip codes for calculations; however, a small number of census tracts fell between 2 zip codes. We used ArcGIS version 10.0 (ESRI, Redlands, CA) to correct these rare occurrences by matching the 2000 Census tract to the zip code in which the majority of the census tract fell. Following calculation of each sociogeographic exposure index, we matched each value to a patient by his or her race and zip code of residence at TB diagnosis.

As previously described, in 2001, New York City began routinely genotyping initial isolates of all patients with TB with a positive culture for Mycobacterium tuberculosis by using both spacer oligonucleotide typing (spoligotyping) and IS6110-based restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) techniques.21 For this analysis, we defined a TB strain by a combination of spoligotype and RFLP result. We considered a patient with TB clustered if the patient’s isolate had a matching spoligotype result and RFLP pattern to another New York City–verified patient’s isolate during the study period. We used clustering of strains as a surrogate for recent transmission and coded it as yes or no, and only for those individuals having culture-positive TB and a TB strain available.

We used SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) for statistical analysis, including incidence calculations and univariate analysis with the Pearson χ2. In comparison testing of categorical variables, we considered differences among cell distributions significant when P < .05. To further evaluate transmission epidemiology, we constructed 2 separate logistic regression models fit with generalized estimating equations to determine which factors were associated with clustering.

RESULTS

During 2001 to 2009, there were 8953 individuals with TB confirmed in New York City. Among these patients, 512 (6%) reported a NYCHA residence at the time of TB diagnosis. The average NYCHA population (minus the number of NYCHA patients with TB) and the average non-NYCHA population (minus the number of non-NYCHA patients with TB) throughout the study were 413 131 and 7 767 332, respectively. Individuals residing in NYCHA developments were more likely to be a patient with TB (P = .004). The New York City neighborhoods with the highest number of patients with TB residing in NYCHA developments were also the neighborhoods with the highest number of NYCHA residents in 2009 (Figure A available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). The number of patients with TB residing in NYCHA and non-NYCHA housing declined from 2001 to 2009 (83 to 41 and 1150 to 716, respectively), and the percentage of overall patients with TB that were NYCHA residents ranged from 4% to 7%.

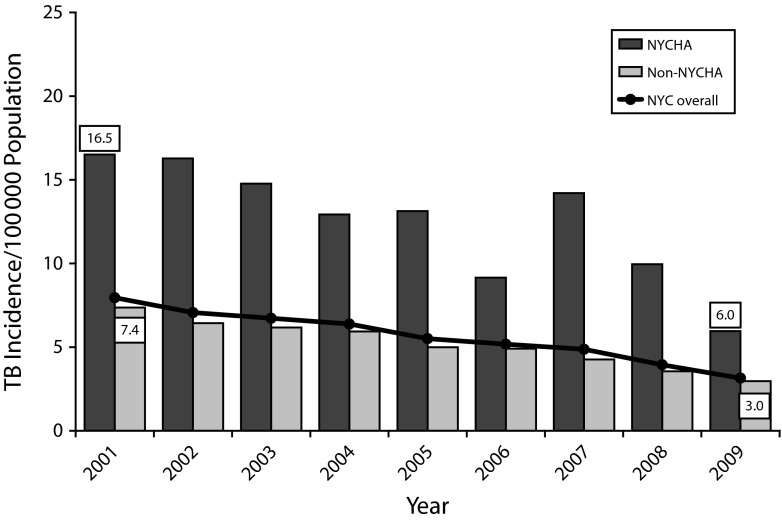

Tuberculosis incidence rates among both NYCHA and non-NYCHA residents declined from 2001 to 2009 (Figure 1). Overall, the incidence of TB among NYCHA residents was higher than among non-NYCHA residents (19.7/100 000 population vs 15.1 in 2001 and 10.2 vs 9.0 in 2009). Among the US-born, TB incidence rates declined among both NYCHA and non-NYCHA residents throughout the study period (Figure 2). However, the TB incidence rate among NYCHA residents was twice that in non-NYCHA residents (16.5 vs 7.4 in 2001 and 6.0 vs 3.0 in 2009).

FIGURE 1—

Incidence of Tuberculosis Among the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) Population vs the Non-NYCHA New York City Population by Year, and the Overall New York City Tuberculosis Incidence by Year: 2001–2009

Note. NYC = New York City; TB = tuberculosis.

FIGURE 2—

Incidence of Tuberculosis Among the US-Born New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) Population vs the US-Born Non-NYCHA New York City Population by Year, and the Overall US-Born New York City Tuberculosis Incidence by Year: 2001–2009

Note. NYC = New York City; TB = tuberculosis. US-born populations were estimated as a percentage of the total population.

Residents of NYCHA with TB were more likely to be older, female, non-Hispanic Black, US-born, HIV-infected, part of a TB cluster, recently unemployed, and have substance use in the past year compared with non-NYCHA residents with TB (all P < .05), and were less likely to be non-Hispanic White or Asian (P < .05). There were no significant differences between NYCHA and non-NYCHA residents with TB regarding drug-resistant strains, history of homelessness, and having a TB strain available.

Among the sociogeographic exposure indices, NYCHA residents with TB were more likely than non-NYCHA residents with TB to have high exposure to poverty (84% vs 52%; P < .001) and less likely to have high exposure to severe overcrowding (31% vs 45%; P < .001), residential racial concentration (13% vs 18%; P = .005), and local foreign-born population (4% vs 37%, P < .001). There was no difference in likelihood of having high exposure to residential racial segregation (33% vs 31%; P = .119).

US-born NYCHA residents with TB were more likely than US-born non-NYCHA residents with TB to be female and non-Hispanic Black (all P < .05), and less likely to have a history of homelessness (P < .05; Table 1). There were no significant differences between the US-born NYCHA and US-born non-NYCHA TB populations regarding age group, recent unemployment, recent substance use, and being part of a TB cluster.

TABLE 1—

Demographic, Clinical, and Social History Characteristics of US-Born New York City Patients With Tuberculosis by New York City Housing Authority Residence: 2001–2009

| US-Born NYC Patients With TB |

|||

| Characteristic | NYCHA Residents, No. (%) | Non-NYCHA Residents, No. (%) | P |

| Total | 371 (14) | 2280 (86) | |

| Age group, y | .06 | ||

| 0–18 | 28 (8) | 279 (12) | |

| 19–44 | 141 (38) | 812 (36) | |

| 45–64 | 138 (37) | 787 (35) | |

| ≥ 65 | 64 (17) | 402 (18) | |

| Male gender | 186 (50) | 1405 (62) | < .001 |

| Race/ethnicity | < .001 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 10 (3) | 355 (16) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 266 (72) | 1241 (54) | |

| Asian | 0 (0) | 61 (3) | |

| Hispanic | 94 (25) | 619 (27) | |

| Other | 1 (< 1) | 4 (< 1) | |

| History of previous TB | 20 (5) | 95 (4) | .28 |

| History of homelessness | 28 (8) | 272 (12) | .01 |

| HIV status | .02 | ||

| Infected | 89 (24) | 675 (30) | |

| Not infected | 198 (53) | 1042 (46) | |

| Refused, not done, not offered, or unknown | 84 (23) | 563 (25) | |

| History of substance use in past year | 126 (35) | 788 (36) | .69 |

| Recent unemployment (in past 24 mo) | 283 (76) | 1701 (75) | .49 |

| History of mental illness | 30 (8) | 230 (10) | .24 |

| Site of disease | .93 | ||

| Pulmonary TB only | 249 (67) | 1553 (68) | |

| Extrapulmonary TB only | 81 (22) | 483 (21) | |

| Both pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB | 41 (11) | 244 (11) | |

| Acid-fast bacilli sputum smear–positive TBa | 157 (54) | 847 (47) | .001 |

| Cavities on chest radiographa | 63 (22) | 319 (18) | .1 |

| Culture-positive TB | 275 (74) | 1616 (71) | .2 |

| Strain availableb | 265 (96) | 1526 (94) | .19 |

| Clustered TB strainc | 178 (67) | 1004 (66) | .66 |

Note. NYC = New York City; NYCHA = New York City Housing Authority; TB = tuberculosis.

Calculated as a percentage of pulmonary cases, which includes pulmonary and both pulmonary and extrapulmonary cases.

A TB specimen with IS6110-based restriction fragment length polymorphism and spacer oligonucleotide type results, as a percentage of those with culture-positive TB.

Those with a TB strain genotype that is part of a known NYC TB cluster, as a percentage of those with restriction fragment length polymorphism and spacer oligonucleotide type results.

Among all US-born and foreign-born culture-positive patients with TB living in NYCHA developments (n = 379), 364 (96%) had a TB strain result available (data not shown). There were 225 patients living in NYCHA developments with a TB strain that was part of a known New York City cluster (62%). In total, 120 distinct TB clusters and 139 unique noncluster TB strains comprised 259 TB strains among patients living in NYCHA developments. Of the New York City TB clusters having at least 1 NYCHA resident, the median cluster size was 4 patients (range = 2–183 patients). The median number of patients with TB residing in NYCHA who were part of a distinct cluster having at least 1 NYCHA resident was 1 patient (range = 1–21 patients). Among the 6417 non-NYCHA culture-positive patients with TB, 6057 (94%) had a TB strain result available. There were 2723 patients with TB not living in NYCHA developments having a TB strain that was part of a known New York City cluster (45%). In total, 744 distinct TB clusters and 3334 unique noncluster strains comprised 4078 TB strains among patients not living in NYCHA developments. Of the New York City TB clusters having at least 1 non-NYCHA resident, the median cluster size was 2 patients (range = 2–183 patients). The median number of patients with TB not residing in NYCHA who were part of a distinct cluster having at least 1 non-NYCHA resident was 2 patients (range = 1–162 patients).

Among NYCHA residents who had a TB isolate with strain results, factors associated with clustering were US birth (odds ratio [OR] = 2.31; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.25, 4.29), being aged 0 to 18 years (OR = 7.59; 95% CI = 4.11, 14.02) and 19 to 44 years (OR = 2.71; 95% CI = 1.65, 4.43) versus being aged 65 years and older, substance use in the past year (OR = 2.93; 95% CI = 1.78, 4.81), and extreme exposure to the sociogeographic measures (OR = 5.26; 95% CI = 1.16, 23.91; Table 2). Asian race (OR = 0.15; 95% CI = 0.03, 0.72) and high exposure to severe overcrowding (OR = 0.50; 95% CI = 0.35, 0.72) were negatively associated with clustering. Among non-NYCHA residents who had a TB isolate with strain results, factors associated with clustering were US birth (OR = 2.81; 95% CI = 2.29, 3.46); being aged 0 to 18 years (OR = 3.09; 95% CI = 2.20, 4.35), 19 to 44 years (OR = 2.47; 95% CI = 2.07, 2.94), and 45 to 64 years (OR = 2.10; 95% CI = 1.75, 2.53) versus being aged 65 years and older; male gender (OR = 1.20; 95% CI = 1.08, 1.34); Hispanic or non-Hispanic Black race (OR = 1.89; 95% CI = 1.47, 2.42; and OR = 1.85; 95% CI = 1.45, 2.37; respectively); substance use in the past year (OR = 1.35; 95% CI = 1.20, 1.53); extreme exposure to the sociogeographic measures (OR = 1.31; 95% CI = 1.12, 1.54); and history of homelessness (OR = 1.30; 95% CI = 1.03, 1.66).

TABLE 2—

Factors Associated With Being Part of a Tuberculosis Cluster Among New York City Housing Authority Patients With Tuberculosis vs Non–New York City Housing Authority New York City Patients With Tuberculosis: 2001–2009

| Covariatea | Patients Living in NYCHA (n = 362), AOR (95% CI) | Patients Living Outside of NYCHA (n = 6035), AOR (95% CI) |

| Birth in the United States (includes all US territories) | ||

| Yes | 2.31 (1.25, 4.29) | 2.81 (2.29, 3.46) |

| No (Ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Age group, y | ||

| 0–18 | 7.59 (4.11, 14.02) | 3.09 (2.20, 4.35) |

| 19–44 | 2.71 (1.65, 4.43) | 2.47 (2.07, 2.94) |

| 45–64 | 1.23 (0.73, 2.05) | 2.10 (1.75, 2.53) |

| ≥ 65 (Ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 0.84 (0.58, 1.21) | 1.20 (1.08, 1.34) |

| Female (Ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Race | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.31 (0.09, 1.08) | 1.85 (1.45, 2.37) |

| Hispanic | 0.33 (0.09, 1.13) | 1.89 (1.47, 2.42) |

| Asian | 0.15 (0.03, 0.72) | 0.86 (0.65, 1.15) |

| Other | 0.15 (0.01, 1.52) | 0.79 (0.42, 1.49) |

| Non-Hispanic White (Ref) | 1 | 1 |

| History of substance use in past year | ||

| Yes | 2.93 (1.78, 4.81) | 1.35 (1.20, 1.53) |

| No (Ref) | 1 | 1 |

| High exposure to ≥ 4 sociogeographic measures | ||

| Yes | 5.26 (1.16, 23.91) | 1.31 (1.12, 1.54) |

| No (Ref) | 1 | 1 |

| High exposure to overcrowding | ||

| Yes | 0.50 (0.35, 0.72) | NA |

| No (Ref) | 1 | NA |

| History of mental illnessb | ||

| Yes | NA | 1.35 (0.97, 1.88) |

| No (Ref) | NA | 1 |

| History of homelessness | ||

| Yes | NA | 1.30 (1.03, 1.66) |

| No (Ref) | NA | 1 |

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; NA = not applicable; NYC = New York City; NYCHA = New York City Housing Authority; TB = tuberculosis.

Both models always included US birth, age, gender, and race. Other a priori covariates were tested, including any substance use in past year, HIV status, borough of residence, recent unemployment, history of mental illness, history of homelessness, high exposure to poverty, high exposure to severe overcrowding, high exposure to residential racial segregation, high exposure to residential racial concentration, high exposure to local foreign-born population, and high exposure in ≥ 4 of the aforementioned sociogeographic indices.

History of mental illness, despite being nonsignificant by our criterion, was retained in the final model for patients living outside of NYCHA because it provided significant predictive value during model construction.

DISCUSSION

We identified disparities in TB rates between NYCHA and non-NYCHA residents in New York City. Despite NYCHA residents comprising 5% of the New York City population during the study period,10 NYCHA residents made up 6% of New York City’s patients with TB population. Because more than two thirds of New York City patients with TB were foreign-born and NYCHA residents were predominately US-born, US-born NYCHA residents compared with US-born non-NYCHA residents was a more appropriate comparison. When we compared the TB incidence among US-born residents, the disparity increased as NYCHA residents had twice the TB incidence than that of non-NYCHA residents. The 2 US-born groups were similar with regard to demographic, clinical, and social characteristics. The overall differences between NYCHA and non-NYCHA residents could be attributed to the higher number of foreign-born individuals among non-NYCHA residents. Therefore, the disparity identified may be because the US-born NYCHA residents have a higher concentration of individuals with risk factors for TB than the general US-born non-NYCHA population.

We conducted an analysis of the strain diversity in the NYCHA TB population to assess whether TB transmission was occurring between residents. Low strain diversity among NYCHA residents, indicated by a large proportion of patients having a TB strain matching 1 of a small number of TB strain clusters, would have suggested transmission among NYCHA residents. Conversely, high strain diversity among NYCHA residents, consisting of many different TB strains among patients and a small proportion of clustering, would have suggested that transmission happened through other means.

There were 259 unique strains among the 364 NYCHA persons with TB, indicating high strain diversity in this population. High strain diversity among NYCHA persons with TB suggests that transmission between NYCHA residents was rare. Furthermore, few clusters had more than 1 NYCHA resident having TB, implying that any transmission associated with NYCHA residency was limited. Although there was 1 cluster including 21 patients with TB with a NYCHA residence, the strain associated with that cluster is endemic to New York City, the cluster had 162 patients not having a NYCHA residence, and the 21 patients having a NYCHA address were distributed among 17 different NYCHA addresses. If TB transmission were happening in NYCHA, we would expect to have seen a small number of clusters with many NYCHA residents with TB; however, we did not see this. This suggests that transmission was not necessarily occurring among NYCHA residents.

Among NYCHA and non-NYCHA residents in the study population, similar factors were associated with TB clustering. In both populations, US birth, younger age, recent substance use, and high exposure to 4 or more sociogeographic measures (poverty, severe overcrowding, residential racial segregation, residential racial concentration, or local foreign-born population) were positively associated with clustering. The overlap in some of the risk factors in this study demonstrates that higher TB incidence in NYCHA is more likely the result of its higher concentration of individuals with known TB risk factors rather than some aspect of housing quality or resident interaction.

There were limitations to the study. First, individual-level data of NYCHA residents were not available for certain measures. Therefore, we used head-of-household characteristics as a surrogate measure for variables, such as the proportion of NYCHA residents that were US-born. Second, we based denominator data on officially reported figures, which may not include unreported additional tenants within residences. Third, data on the length of individuals’ residence in NYCHA developments were not available, though the average residency was known to be 20 years. Fourth, social history variables such as substance use may have been subject to reporting bias. Fifth, use of surrogate measures to estimate the population at risk naturally yielded imprecise incidence measures, and should be considered best estimates rather than true incidence.

Strengths of this study include the large study population size, high completeness of patient address data used to assign NYCHA residence, high capture of TB cases in New York City, and availability of TB strain results for nearly all individuals with TB. With almost 9000 individuals having TB over the 9-year study period, there was adequate power to detect meaningful differences between the demographic, clinical, and social history characteristics. With the long observation period of 9 years and the availability of genotyping data, our study was able to provide a better understanding of TB transmission over a longer time frame than many previous studies, perhaps better reflecting the natural course of TB transmission and pathogenesis.

As a disease that increasingly affects hard-to-reach populations, TB presents challenges for TB-control programs whose primary mission is to prevent and cure TB.22 Identifying populations at high risk for developing TB to engage them in prevention activities is critical to the success of TB control programs in both global and local contexts. The NYCHA is the largest public housing authority in North America, with more than 400 000 residents living in more than 350 developments in all 5 boroughs of New York City. The health of public housing residents has been shown to be poorer than that of their neighbors in various studies,23,24 but this has been shown to be the result of public housing’s role as a social safety net rather than a result of housing quality.25

Although this study has shown that TB transmission between NYCHA residents is not a primary mode of transmission, and thus New York City DOHMH does not need to intervene on such a pathway, the overall NYCHA population still has a relatively high burden of TB. Because the NYCHA population is well-defined both demographically and geographically and has a relatively static population with an average residency of 20 years, this population is accessible to public health authorities and can be engaged in ongoing TB prevention activities. However, because public housing residents tend to have more health challenges than non–public housing residents,23,24 efforts to reduce the burden of TB among them should not be enacted in isolation of other health promotion activities. A comprehensive approach that targets a multitude of this population’s unique health needs is warranted. In light of the rising prevalence of type 2 diabetes and other obesity-related conditions, more work is needed to address the role of comorbidities in TB reactivation among New Yorkers. New York City DOHMH, through district public health offices, is working to address the primary health concerns of the population in its catchment area,26 and should continue to be supported. Tuberculosis control program staff plan to work collaboratively with district public health offices and NYCHA administrators to better target the NYCHA population for TB screening and treatment of TB infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was presented at the American Thoracic Society International Conference, May 2012.

The authors thank the New York City Housing Authority, especially Anne-Marie Flatley, as well as Bureau of Tuberculosis Control staff and the Epi Scholars Program in Health Disparities, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. The authors also wish to thank our genotyping laboratory partners, the New York City Public Health Laboratory (New York, NY), Public Health Research Institute at Rutgers University (Newark, NJ), New York State Department of Health Wadsworth Center (Albany, NY), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, GA).

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

This study was approved by the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene institutional review board and conducted with the support of New York City Housing Authority.

REFERENCES

- 1.TB Annual Summary: 2006. New York, NY: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Acevedo-Garcia D. Zip code–level risk factors for tuberculosis: neighborhood environment and residential segregation in New Jersey, 1985–1992. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(5):734–741. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.5.734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Acevedo-Garcia D. Residential segregation and the epidemiology of infectious diseases. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(8):1143–1161. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Small PM, Hopewell PC, Singh SP et al. The epidemiology of tuberculosis in San Francisco: a population-based study using conventional and molecular methods. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(24):1703–1709. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406163302402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Driver CR, Kresiworth B, Macaraig M et al. Molecular epidemiology of tuberculosis after declining incidence, New York City, 2001–2003. Epidemiol Infect. 2007;135(4):634–643. doi: 10.1017/S0950268806007278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barr RG, Diez-Roux AV, Knirsch CA et al. Neighborhood poverty and the resurgence of tuberculosis in New York City, 1984–1992. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(9):1487–1493. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.9.1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.TB Annual Summary: 2013. New York, NY: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alami NN, Yuen CN, Miramontes R et al. Trends in tuberculosis—United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(11):229–233. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.TB Annual Summary: 2012. New York, NY: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.New York City Housing Authority. About NYCHA fact sheet. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/nycha/html/about/factsheet.shtml. Accessed November 8, 2014.

- 11.New York, NY: New York City Housing Authority; 2009. 2009 New York City Housing Authority resident characteristics dataset. [Google Scholar]

- 12.US Census Bureau. Population estimates. Available at: http://www.census.gov/popest. Accessed August 2, 2013.

- 13.New York City Department of City Planning. Population. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/dcp/html/census/popcur.shtml. Accessed August 2, 2013.

- 14.US Census Bureau. 2002 New York City Housing and Vacancy Survey. Available at: http://www.census.gov/housing/nychvs/data/2002/nychvs02.html. Accessed February 22, 2015.

- 15.Jargowsky PA. Poverty and Place: Ghettos, Barrios, and the American City. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawachi I, Kennedy BP. Socioeconomic determinants of health: health and social cohesion: why care about income inequality? BMJ. 1997;314(7086):1037–1040. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7086.1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Massey DS. The age of extremes: concentrated affluence and poverty in the twenty-first century. Demography. 1996;33(4):395–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duncan OD, Duncan B. A methodological analysis of segregation indexes. Am Sociol Rev. 1955;20(2):210–217. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Massey DS, Denton NA. American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Massey DS, Denton NA. The dimensions of residential segregation. Soc Forces. 1988;67:281–315. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clark CM, Driver CR, Munsiff SS et al. Universal genotyping in tuberculosis control program, New York City, 2001–2003. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(5):719–724. doi: 10.3201/eid1205.050446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Global Tuberculosis Control: Surveillance, Planning, Financing. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fertig AR, Reingold DA. Public housing, health, and health behaviors: is there a connection? J Policy Anal Manage. 2007;26(4):831–859. doi: 10.1002/pam.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howell E, Harris LE, Popkin SJ. The health status of HOPE VI public housing residents. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2005;16(2):273–285. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2005.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruel E, Oakley D, Wilson GE, Maddox R. Is public housing the cause of poor health or a safety net for the unhealthy poor? J Urban Health. 2010;87(5):827–838. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9484-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. District Public Health Offices: New York City’s commitment to healthier neighborhoods. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/diseases/dpho-homepage.shtml. Accessed August 17, 2014.