Brentuximab vedotin (BV) is an antibody-drug-conjugate directed against CD30 antigen, recently approved for the treatment of relapsed anaplastic large-cell lymphomas (ALCL).1 It has further been suggested that a significant proportion of peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCL) may be potential candidates for CD30-targeting strategies. Indeed, besides ALCL, CD30 is also expressed by neoplastic cells of lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) and transformed mycosis fungoïdes (MF), whereas its expression is more heterogeneous among systemic PTCL. Only 15% of non-ALCL PTCL exhibit a strong CD30 expression (in >75% of tumor cells) including a majority of enteropathy associated T-cell lymphomas (EATL) and around 25% of PTCL not otherwise specified (PTCL-NOS). In contrast, angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphomas (AITL) and adult T-cell lymphomas (ATLL) usually express CD30 in less than 10% of tumor cells.2,3 Interestingly, three recent phase II studies of systemic non-ALCL PTCL and cutaneous T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders reported that BV may be effective even in PTCL without significant expression of CD30.4,5,6

We conducted a retrospective multicenter study on a cohort of relapsed or refractory PTCL patients treated with BV during the named patient program in France, in an attempt to better define the patient population with the highest benefit from this type of therapy.

Between March 2011 and January 2014, 56 patients with a confirmed diagnosis of PTCL according to the 2008 WHO classification were treated with BV as monotherapy, administered as in the pilot phase II trial.1 For the purpose of the current study, the tumor samples of 46 cases were centrally reviewed and assessed for CD30 by immunohistochemistry, using a semi-quantitative 5-tiered scale (0=<5%, I=5–24%, II=25–49%, III=50–75%, IV>75% of CD30 positive tumor cells).2

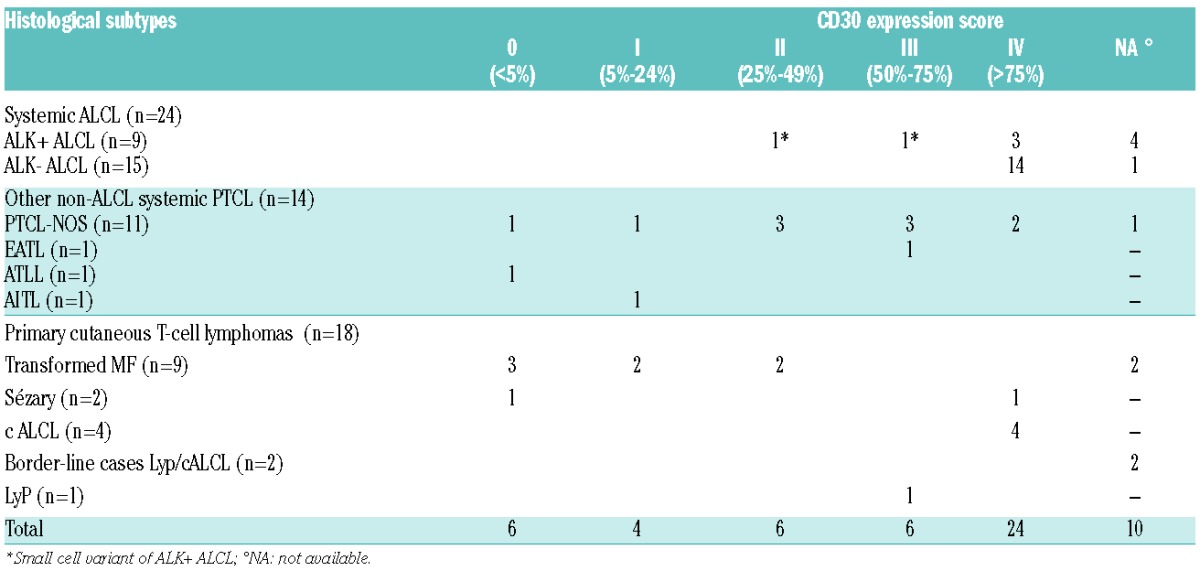

At the time of BV therapy, our study population was middle-aged [58 years (range: 19–83)] and 66% were male. Most patients had stage III–IV (n=44; 85%). Median number of lines of therapies previously given was 3 (range: 1–8). Eighteen patients (31%) were considered to be primary refractory. With a median of 4.6 months (range: 3.2–21.1 months), 8 patients (14%) had progressed after autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) and 3 (5%) had relapsed after allogeneic transplant (allo-SCT). With respect to their most recent treatment, 32 patients (57%) were considered to be refractory and 23 (41%) to be in relapse. The 56 PTCL patients were classified as ALK- ALCL (n=15, 27%), PTCL-NOS (n=11, 20%), ALK+ ALCL (n=9, 16%), transformed MF (n=9, 16%), CD30+ primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders (LPD) (n=7, 12%; including 4 cALCL, 1 LyP and 2 border-line cases between cALCL and LyP), Sézary syndrome (SS) (n=2, 3%), ATLL (n=1, 2%), EATL (n=1, 2%), and AITL (n=1, 2%). Owing to the histological heterogeneity, patients were further put into 3 clinico-pathological groups,7 defined as “systemic ALCL” including ALK- and ALK+ ALCL (n=24, 43%), “primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas” including MF, SS and cutaneous CD30+ LPD (n=18, 32%) and “non-ALCL systemic PTCL” including AITL, ATLL, EATL and PTCL-NOS (n=14, 25%). Among the 46 patients with central CD30 scoring, CD30 expression was highly variable from case to case, ranging from 0 to 100%, and correlated with PTCL pathological subtypes.2,3 Overall, 24 cases (52%) showed a strong CD30 expression (score IV). As expected, this group was made up of ALK- ALCL (n=14), cALCL (n=4), ALK+ ALCL (n=3), PTCL-NOS (n=2), and one case of SS. Interestingly, 6 patients (13%) (including 3 MF, one SS, one PTCL-NOS, and one ATLL) were scored 0 both on the tumor cells and on the microenvironment cells. The remaining cases were scored I (n=4, 9%), II (n=6, 13%) and III (n=6, 13%), respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Correlation between CD30 expression and histological subtypes.

Patients received a median of 6 cycles of BV (range: 1; 16). Only 7 of 56 patients (12.5%) completed the 16 cycles scheduled. Doses of BV were reduced in 11 patients (19%) because of toxicity (neuropathy: n=3; hepatic cytolysis: n=1; neutropenia and thrombocytopenia: n=2; weight loss, n=3; unknown cause: n=2). Adverse events led to treatment discontinuation in 5 patients (9%). As previously described,1 the most common (>20%) adverse events emerging from treatment of any grade were peripheral neuropathy (n=20, 53%), cytopenia (anemia: n=19, 51%; neutropenia: n=15, 42%), thrombocytopenia (n=14, 37%) and infections (n=10, 29%).

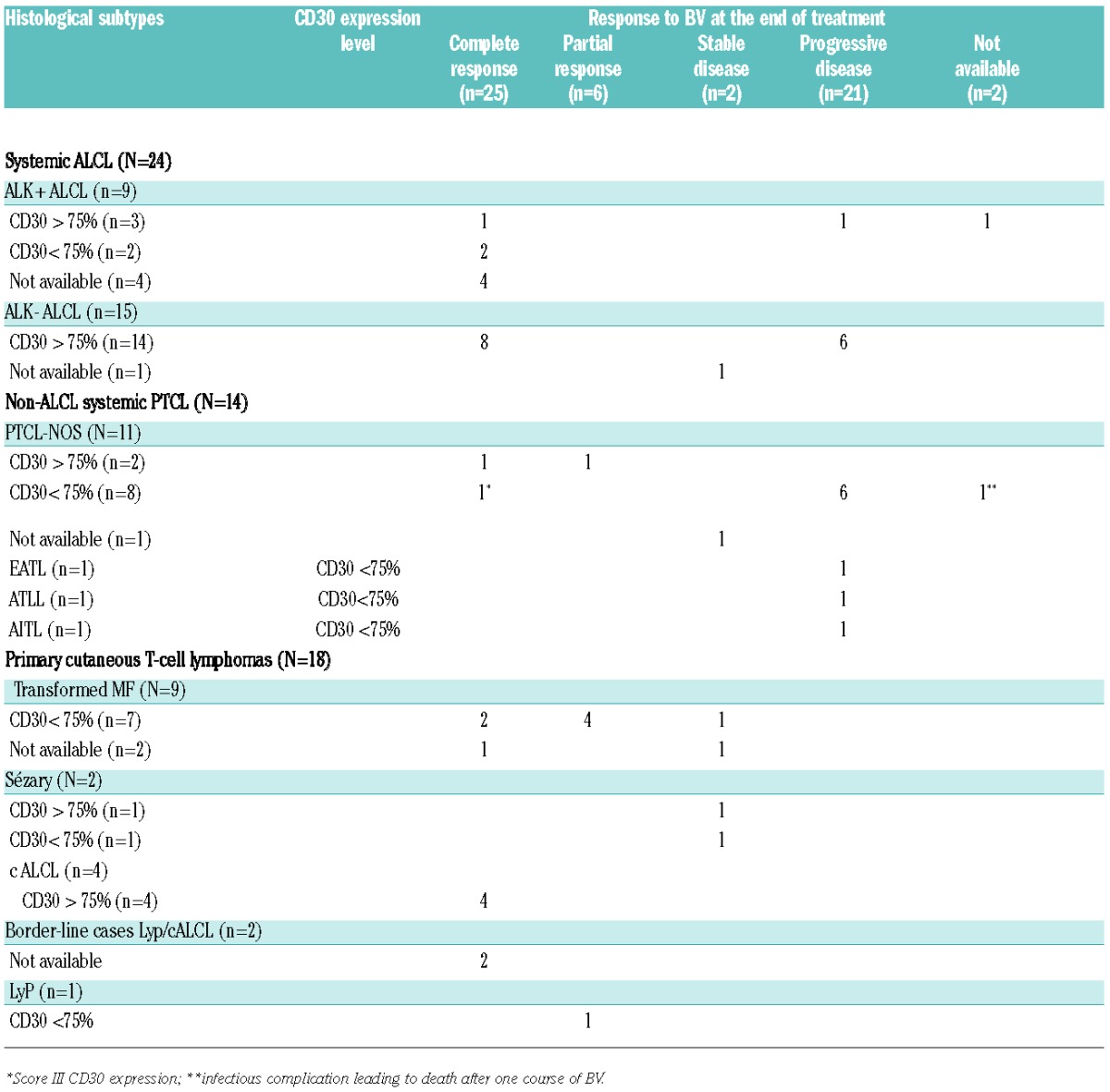

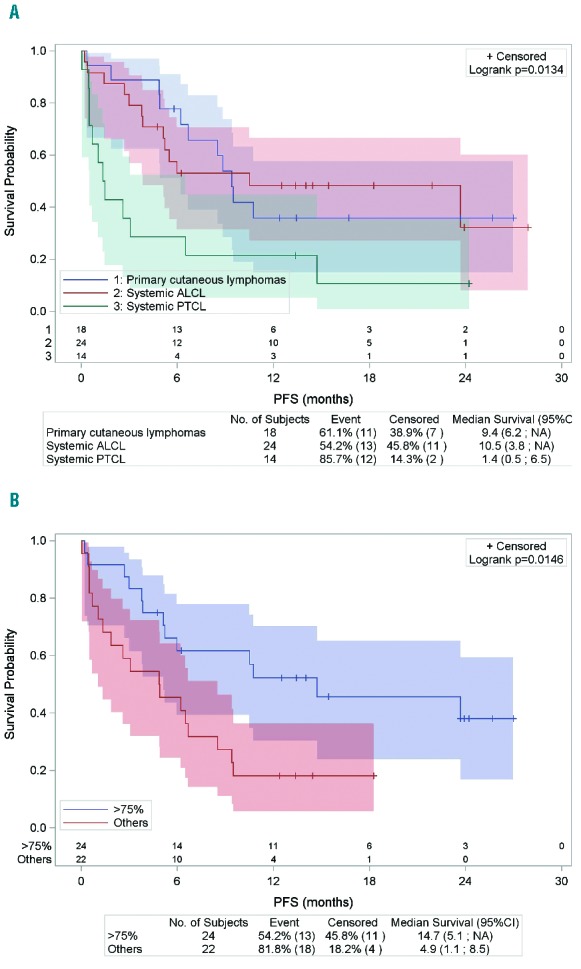

With respect to the clinico-pathological groups, patients with primary cutaneous lymphomas (n=18) (entities known to differ in their clinical presentation and outcome from systemic PTCL7) had an ORR at the end of treatment of 72% and a median PFS of 9.4 months (95%CI: 6.2; NR), which is consistent with the previous results of the phase II studies published by Duvic et al. and Kim et al.5,6 Patients with systemic ALCL (n=24) had a better ORR than patients with non-ALCL systemic PTCL (n=14), with an ORR at the end of treatment of 62% (n=15) and 21% (n=3), respectively (P=0.04) (Table 2). Moreover, more than half of the patients with non-ALCL systemic PTCL rapidly progressed during the first two cycles of BV. Consequently, the median PFS of patients with systemic ALCL was significantly better than that of patients with non-ALCL systemic PTCL (10.5 vs. 1.4 months; P=0.01) (Figure 1A). These results, obtained in a population of patients treated in a non-clinical trial setting, confirm the promising results of the pivotal phase II study in systemic ALCL patients,1 and support BV as an effective treatment for relapsed or refractory systemic ALCL. Conversely, the efficacy of BV in non-ALCL systemic PTCL patients is more disappointing, in accordance with the results reported by Horwitz et al.4 Newly diagnosed systemic ALCL, even the ALK-negative subset, have a better prognosis than non-ALCL systemic PTCL.8 However, whether this prognostic advantage is maintained at relapse is still a matter of debate. Yet recent data from Mak et al. did not indicate any differences in outcome between patients with various systemic PTCL subtypes at relapse, even systemic ALCL, who cannot undergo hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.9 Altogether, these data further suggest that BV especially improves the outcome of ALCL patients at relapse compared to non-ALCL PTCL.

Table 2.

Response to brentuximab vedotin according to histological subtypes and CD30 expression.

Figure 1.

(A) Progression-free survival according to histological subtypes (n=56). *PFS is reported from the time of the first cycle of BV. (B) Progression-free survival according to CD30 expression (>75% vs. others) (n=46). *PFS is reported from the time of the first cycle of BV.

The question of a threshold of CD30 expression by tumor cells required for efficacy of BV remains an open issue. We correlated CD30 expression and response to BV therapy. Overall, the ORR of patients with score IV (n=24 of 46, 52%) and score 0 to III (n=22 of 46, 48%) were 62% and 41%, respectively, with an impact on PFS as the median PFS was longer for patients with score IV than for the remaining patients (14.7 vs. 4.9 months; P=0.01) (Figure 1B). Although the correlation between CD30 expression and ORR or PFS is significantly influenced by histology, as 17 of the 24 score IV patients corresponded to ALCL patients, it is noteworthy that this trend toward a better response to BV for patients with a high level of CD30 expression by tumor cells was also observed when focusing on non-ALCL systemic PTCL patients. Indeed, the 2 non-ALCL PTCL patients who scored IV reached at least PR, whereas 9 of the 11 patients with a score of 0 to III of CD30 expression level rapidly progressed during BV therapy (Table 2). To date, four studies have already addressed this issue and failed to demonstrate any correlation between response to BV and the level of CD30 expression on tumor cells.4,5,6,10 In the previous report on systemic non-ALCL PTCL,4 more than 80% of the cases featured no or low levels of CD30 expression (<25% of CD30+ tumor cells), and as in our study, some patients with only a weak CD30 expression on tumor cells responded to BV, raising the question of the mechanism of BV action in these cases. However, the heterogeneity of CD30 expression in our population highlights the likelihood for better response for patients with strong CD30 expression by tumor cells.

With a median follow up of 13.4 months (range 0.4–28.9), 35 patients (62%) were alive and half of them (n=18) were in persistent CR. Ten patients were still in CR after BV without any consolidation, including 4 ALK-ALCL, 3 ALK+ ALCL, 2 cALCL and one PTCL-NOS with a score IV CD30 expression. After BV, 7 patients in CR (2 ALK+ ALCL, 2 ALK- ALCL, 2 primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas and 1 PTCL NOS) proceeded to ASCT whereas 6 patients (3 ALK+ ALCL in CR and 3 primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas in PR) underwent allogeneic transplant (allo-SCT) with a one-year PFS rate of 68.6% and 44%, respectively. Only one patient died after allo-SCT from lymphoma progression. These promising results are in accordance with those of the pivotal study of BV showing that the median PFS of 15 systemic ALCL patients who received allo-SCT while in CR was not reached, whereas the median PFS for patients in CR with no post BV SCT was 37.7 months.1,11,12

In conclusion, our data support BV as an effective treatment for relapsed or refractory systemic ALCL and primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma patients. The more disappointing results in non-ALCL systemic PTCL, especially for those with a low level of CD30 expression by tumor cells, needs to be confirmed in larger prospective trials combining PTCL patients with different pathological subtypes and CD30 expression scoring to determine the potential predictive value of CD30 expression level.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the LYSARc for its expert assistance with histological techniques (Caroline Communaux, Nadine Vailhen), statistical analyses and reporting (Marion Fournier, Sophie Pallardy and Sami Boussetta), the clinicians of the LYSA who contributed to the collection of clinical data [T. Braun (Hôpital Avicenne), K. Bouabdallah (CHU Bordeaux), A. Delmer (CHU de Reims), V. Delwail (CHU Poitiers), M. D’Incan (CHU Clermont-Ferrand), A. Fauconneau (CHU Bordeaux), S. François (CHU Angers), L. Fornecker (CHU Strasbourg), S. Garciaz (Institut Paoli-Calmettes Marseille), L. Karlin (CHU Lyon), M. Lenoble (CHI Le Raincy-Montfermeil), A.Perrot (CHU Nancy), G. Salmeron (CHG Versailles), L. Terriou (CHRU Lille)] and the pathologists who gave access to the tumor tissue block for the review process [G. Averous (CHU Strasbourg), B. Balme (CHU Lyon), J. Bruneau (Hôpital Necker, Paris), A. Croue (CHU Angers), S. Bisiau (Valenciennes), V. Bodiguel (Hôpital Montfermeil), F. Charlotte (Hôpital Pitié-Salpétrière, Paris), C. Chassagne-Clement (Lyon), MC Copin (CHU Lille), M. Corre-Delages (CHU Limoges), L. Deschamps (Hôpital Bichat), F. Franck (CHU Clermont-Ferrand), A. Frassatti-Biaggi (Hôpital Jean Verdier, Bondy), J-F Jazeron (La Rochelle), M. Grossin (Hôpital Louis Mourrier), P. Levillain (CHU Poitiers), L. Marcellin (CHU Strasbourg), A. Martin (Hôpital Avicenne), V. Meignin (Hôpital Saint-Louis), A. Moreau (CHU Nantes), M. Patey (CHU Reims), J-M Picquenot (CHU Rouen), T. Rousset (Montpellier), MT Rousselet (CHU Angers), D. Scrumeda (Caen), V. Verkarre (Hôpital Necker), L. Xerri (IPC, Marseille)].

Footnotes

Information on authorship, contributions, and financial & other disclosures was provided by the authors and is available with the online version of this article at www.haematologica.org.

References

- 1.Pro B, Advani R, Brice P, et al. Brentuximab vedotin (SGN-35) in patients with relapsed or refractory systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma: results of a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(18): 2190–2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bossard C, Dobay MP, Parrens M, et al. Immunohistochemistry as a valuable tool to assess CD30 expression in peripheral T-cell lymphomas: high correlation with mRNA levels. Blood. 2014;124(19):2983–2986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sabattini E, Pizzi M, Tabanelli V, et al. CD30 expression in peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Haematologica. 2013;98(8): 81–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horwitz SM, Advani RH, Bartlett NL, et al. Objective responses in relapsed T-cell lymphomas with single-agent brentuximab vedotin. Blood. 2014;123(20):3095–3100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duvic M, Tetzlaff MT, Gangar P, et al. Results of a Phase II Trial of Brentuximab Vedotin for CD30+ Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma and Lymphomatoid Papulosis. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(32):3759–3765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim YH, Tavallaee M, Sundram U, et al. Phase II Investigator-Initiated Study of Brentuximab Vedotin in Mycosis Fungoides and Sézary Syndrome With Variable CD30 Expression Level: A Multi-Institution Collaborative Project. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(32):3750–3758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vose J, Armitage J, Weisenburger D, et al. International T-Cell Lymphoma Project. International peripheral T-cell and natural killer/T-cell lymphoma study: pathology findings and clinical outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(25):4124–4130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Savage KJ, Harris NL, Vose JM, et al. ALK- anaplastic large-cell lymphoma is clinically and immunophenotypically different from both ALK+ ALCL and peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified: report from the International Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma Project. Blood. 2008;111(12):5496–5504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mak V, Hamm J, Chhanabhai M, et al. Survival of patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma after first relapse or progression: spectrum of disease and rare long-term survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2013; 31(16):1970–1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobsen ED, Sharman JP, Oki Y, et al. Brentuximab vedotin demonstrates objective responses in a phase 2 study of relapsed/refractory DLBCL with variable CD30 expression. Blood. 2015;125(9):1394–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Illidge T, Bouabdallah R, Chen R, et al. Allogeneic transplant following brentuximab vedotin in patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma and systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56(3):703–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pro B, Advani R, Brice P, et al. Four-Year Survival Data from an Ongoing Pivotal Phase 2 Study of Brentuximab Vedotin in Patients with Relapsed or Refractory Systemic Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma. Blood. 2014;124(21):(Abstract 3095). [Google Scholar]