Abstract

I have described a decision support tool that may facilitate local decisions regarding the provision and billing of clinical services. I created a 2 by 2 matrix of health professional shortage and Medicaid expansion availability as of July 2015. I found that health departments in 93% of US counties may still need to provide clinical services despite the institution of the Affordable Care Act. Local context and market conditions should guide health departments’ decision to act as safety net providers.

Because more individuals have health insurance coverage as a result of the Affordable Care Act, health departments grapple with the question of whether to continue to provide clinical services such as maternal and child health, oral health, and HIV/AIDS treatment and, if so, whether to seek reimbursement from third party payers.1 In fact, a 2012 Institute of Medicine report states,

As clinical care provision in a community no longer requires financing by public health departments, public health departments should work with other public and private providers to develop adequate alternative capacity in a community’s clinical care delivery.2(p68)

The decision to provide clinical services and pursue reimbursement is complex,3 and that complexity will likely increase as reimbursement moves to new models such as accountable care organizations. Health departments must decide whether it makes sense to provide clinical services on the basis of local context and, if so, whether to seek reimbursement.4 As of 2013, a minority of local health departments provided clinical services such as maternal and child health, oral health, and HIV/AIDS treatment,5 although a 2014 report showed that, of those who do, the majority bill some form of third party payment.6 I tested a simple decision support tool that might be used to facilitate local decision-making.

METHODS

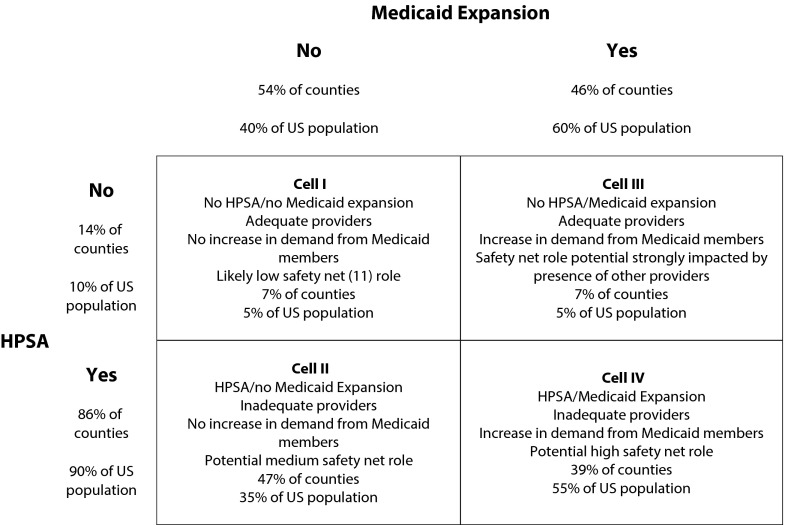

I treated the decision of whether to provide clinical services and seek reimbursement as a supply and demand analysis using a 2 by 2 matrix. When qualitative judgments must be made and visual plotting can aid decision-making, 2 by 2 matrices are particularly useful.7 I plotted each county health department in 1 of 4 quadrants on the basis of whether the state in which it is located is expanding Medicaid (demand) and the county is a designated primary care health professional shortage area (supply).

I obtained the roster of US counties from the US Census Bureau,8 health professional shortage area designation data from the Health Resources and Services Administration Bureau of Health Professions,9 and state Medicaid expansion designations from the Kaiser Family Foundation as of July 2015.10

RESULTS

There were 3115 listed counties: 215 (7%) were in cell I (approximately 5% of the US population in 2014), 1461 (47%) were in cell II (35% of the US population), 218 (7%) were in cell III (5% of the US population), and 1221 (39%) were in cell IV (55% of the US population; Figure 1). A map of these counties is included as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org.

FIGURE 1—

HPSA × Medicaid Expansion: United States, July 2015.

Note. HPSA = health professional shortage area.

DISCUSSION

According to this analysis, health departments in 93% of counties (cells II, III, IV) may need to consider expanding clinical services, whereas those in the remaining 7% of counties (cell I) may have an adequate supply–demand balance. Health departments in 39% of counties may have the greatest opportunity to seek reimbursement for clinical services because of potential Medicaid expansion revenues and a lack of providers.

Although 86% of counties are designated as health professional shortage areas, few health departments provide clinical services.1,5 This may indicate the need for additional safety net support for clinical services from providers such as federally qualified health centers and volunteer clinics. The analysis does not account for those who may not be newly eligible for Medicaid, regardless of a state’s expansion status, further emphasizing the need to tailor results to local context and conditions. However, the analysis does serve to group health departments in broad categories as a first step in working through the decision-making process.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I acknowledge Michelle Rushing for creating the US map.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

No protocol approval was necessary because no human participants were involved in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hsuan C, Rodriguez HP. The adoption and discontinuation of clinical services by local health departments. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(1):124–133. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Institute of Medicine Committee on Public Health Strategies to Improve Health. For the Public’s Health: Investing in a Healthier Future. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Etkind P, Gehring R, Ye J, Kitlas A, Pestronk R. Local health departments and billing for clinical services. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2014;20(4):456–458. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Practical Playbook. Public Health and Primary Care Together. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilhoit J. National Profile of Local Health Departments, 2013. Washington, DC: Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Billing for Clinical Services: Findings From the 2014 Forces of Change Survey. Washington, DC: National Association of County and City Health Officials; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Institute for Manufacturing Department of Engineering. Decision Support Tools: 2x2 matrix. Cambridge, UK: University of Cambridge; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.2010 FIPS Codes for Counties and County Equivalent Entities. Suitland, MD: US Census Bureau; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Health Resources and Services Administration Data Warehouse. Health professional shortage areas. Available at: http://datawarehouse.hrsa.gov. Accessed December 12, 2015.

- 10.Status of State Action on the Medicaid Expansion Decision. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2015. [Google Scholar]