Online geographic tools using “Big Data” have made new approaches for neighborhood health research possible. Examples of neighborhood data available from these tools include crime statistics from the New York Times and EveryBlock, neighborhood walkability scores from Walkscore.com, and restaurant locations and ratings from Yelp. New services, such as geocoding services offered by Google Maps also exist. These online sources improve medical geographic research that examines the effects of neighborhood conditions on health and well-being.

But these new approaches also create new ways to violate human participant protections. Problems arise when researchers pass personally identifiable information—information such as addresses—to online service providers. If researchers use online tools to geocode (i.e., convert addresses to latitude/longitude pairs for geographic analysis) or to gather information about a participant’s neighborhood using the participant’s residential or work address, they release participants’ personally identifiable information to that service. The broad terms of service on most Web sites usually permit those service providers to freely use any data passed to them rather than hew to strict rules established by institutional review board (IRB) protocols to protect human participants.

This problem has received less attention than other privacy problems in medical geography, such as the public presentation of maps that reveal participant locations.1 In fact, many researchers appear to be unaware of these risks. We have read protocols for studies planning to conduct neighborhood audits that include entering participants’ addresses into Google Street View’s interface. Similarly, the instructional video for SSO i-Tour (Systematic Social Observation Inventory—Tallying Observations in Urban Regions) suggests entering study participants’ addresses into Google Earth for geocoding.2 Since Google Earth submits those geocode requests to Google’s online servers, it is unlikely this use of SSO i-Tour would be approved by an IRB that was aware of the geocoding process. Several published articles report submitting study participants’ home addresses to Walkscore.com to acquire measures of neighborhood walkability. The fact that protocols, training materials, and articles were published using these methods indicates that the privacy risks were not fully understood by authors, reviewers, editors, and IRBs.

INAPPROPRIATE METHODS TO COLLECT ONLINE DATA

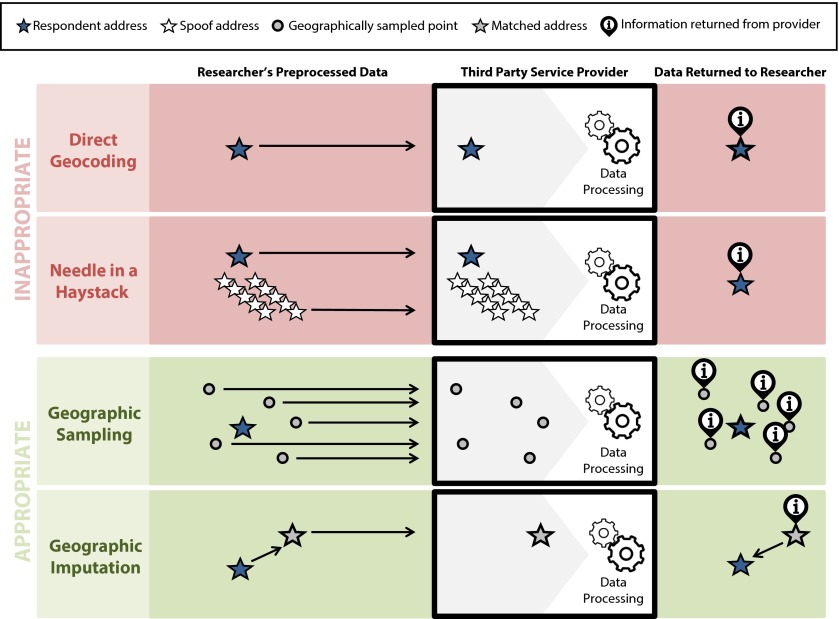

The first row of Figure 1, labeled “Direct Geocoding,” diagrammatically depicts the method we just described and shows the problem that lurks when researchers use the method. The blue star represents the participant’s address. When a researcher uses an online service to geocode an address or to obtain data, the researcher passes the participant’s address to the service provider. Figure 1 represents this process by the blue star in the box representing the service provider. At this point, the participant’s personally identifiable information has been released to a third party.

FIGURE 1—

Using online geographic services appropriately—maintaining study participant confidentiality while using online geographic services to gather contextual data.

One flawed approach some researchers have used involves submitting participants’ addresses along with a very large number of randomly selected addresses. This “security through obscurity” approach conceptually hides a needle (real respondent addresses) in a haystack (of random addresses).3 However, it does not encrypt personally identifiable information, and this fails to comply with typical IRB standards regarding protection of human participant data.3 More broadly, this method does not follow the National Institute of Standards and Technology recommendations to secure data by requiring a key rather than relying on keeping the information itself hidden.4 The second row of Figure 1 reveals the problem: even if one “hides” the participant’s address, the online service provider still receives it.

APPROPRIATE METHODS TO COLLECT ONLINE DATA

However, researchers can use approaches that protect human participants. We did so ourselves when we developed an online application, CANVAS (Computer Assisted Neighborhood Visual Assessment System), that uses Google Street View to gather data about neighborhoods.5,6 We conducted studies without passing identifiable information to Google by using geographic sampling. We sampled streets in cities based on spatial grids, which allowed us to characterize the entire cities without focusing on specific participants’ addresses. Because the sample locations were not linked to specific study participants, we did not pass any identifiable information to Google. We then used kriging, a geostatistical technique, to estimate values of walkability and disorder at the participants’ addresses using an offline desktop geographic information system.6 We depict this process in the third row of Figure 1. Only the geographically sampled points are passed to the online service provider; there is, therefore, no blue star (representing the participant’s address) in the box (representing the service provider).

Alternatively, one could substitute each study participant’s home address with other addresses that are similar on observable characteristics. We term this approach geographic imputation because it solves the problem by treating the addresses as missing data. A popular imputation solution to missing data substitutes the missing data for one participant with data from a similar participant. A researcher could identify streets similar to the participant’s using offline geographic information system tools based on key characteristics like street width, traffic speed, and resident demographic characteristics then randomly select one to observe. This strategy protects personally identifiable information and requires only one observation per participant. Figure 1 depicts the matched address in a lighter shade of blue. The online service provider only receives the substituted address after which the researcher can reconnect to the study participant on his or her own machine with suitable IRB protections.

Geographic sampling is most efficient when study participants cluster in a single region (e.g., a city or part of a city) because the spatial sample leverages the geographic proximity of sample points. Geographic imputation requires only a single observation per participant but ties the contextual data to that specific study. Geographic imputation is best for geographically dispersed samples such as nationally representative samples.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, newly available services that rely on geographic “Big Data” provide researchers with powerful new tools to study the influence of environments on health.7 But researchers, grant and journal reviewers, editors, and IRB members must attend to the privacy issues raised by the use of online tools in human participant research. Transmitting study participants’ addresses or locations to online geospatial services fails to comply with current standards of human participant data protections. Judicious and careful use of offline geospatial tools and spatial statistics along with online services will allow health researchers to leverage these data for innovative health research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brownstein JS, Cassa C, Kohane IS, Mandl KD. Reverse geocoding: concerns about patient confidentiality in the display of geospatial health data. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2005:905. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.adaptlab. Google Street View Project. Available at: http://69.89.27.208/∼adaptlab/gallery/104-2. Accessed March 6, 2015.

- 3.Petitcolas FAP, Anderson RJ, Kuhn MG. Information hiding—a survey. Proc IEEE. 1999;87(7):1062–1078. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scarfone K. Guide to General Server Security: Recommendations of the National Institute of Standards and Technology. Diane Publishing; Collingdale, PA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bader MDM, Mooney SJ, Lee YJ et al. Development and deployment of the Computer Assisted Neighborhood Visual Assessment System (CANVAS) to measure health-related neighborhood conditions. Health Place. 2015;31:163–172. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mooney SJ, Bader MD, Lovasi GS, Neckerman KM, Teitler JO, Rundle AG. Validity of an ecometric neighborhood physical disorder measure constructed by virtual street audit. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180(6):626–635. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mooney SJ, Westreich DJ, El-Sayed AM. Commentary: epidemiology in the era of big data. Epidemiology. 2015;26(3):390–394. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]