Abstract

Toxoplasma gondii is a zoonotic obligatory intracellular protozoan parasite with the capability to infect all warm-blooded animals. One of the great concerns is that it can lead to ovine abortion in sheep growing industry. Different diagnostic methods such as serology, pathology, immunohistochemistry, bioassay and molecular detection have been used in order to detect ovine abortion associated with T. gondii. In this case, an outbreak of congenital toxoplasmosis based on serological, macroscopic, pathological detection and isolation of T. gondii by bioassay is described and emphasized on the importance of this route of transmission that caused lamb losses and an increase in possible sources of infection for human and environment.

Keywords: Ovine abortion, Outbreak, Toxoplasma gondii, Iran

Introduction

Toxoplasma gondii is a zoonotic obligatory intracellular protozoan parasite with the capability to infect all warm-blooded animals. It manifests itself as a disease of pregnancy by multiplying in the placenta and fetus. It was first described by Hartley et al. (1954) which even today is known as one of the major causes of sheep abortion world wide (Buxton 1991). Another characteristic of vertical transmission of T. gondii is that this kind of transmission can occur more frequently than what was previously thought (Duncanson et al. 2001; Morely et al. 2005, 2007; Hide et al. 2009; Innes et al. 2009; Dubey 2009).

Toxoplasma-induced ovine abortion has been linked to food or pasture contamination with sporulated oocysts (Plant et al. 1972) and associations have been made between exposure of sheep to T. gondii and the presence of cats in farms or the circulation of stray cats (Skjerve et al. 1998).

Different diagnostic methods such as serology, pathology, immunohistochemistry, bioassay and molecular detection have been used for diagnosis of ovine abortion associated with T. gondii (Ortega-Mora et al. 2007). These methods have been brought to use based on their suitability for the due study and their capability of confirming the infection.

There are few reports of congenital toxoplasmosis outbreak all around the world but It has been reported that 7–32 % of ovine abortion outbreaks in New Zealand from 1973 to 1989 were caused by T. gondii with higher rates in 1980s (Gumbrell 1990; Orr 1989; Dubey 2009). This kind of outbreak has not been reported in Iran.

In this case, an outbreak of congenital toxoplasmosis based on serological, macroscopic, pathological detection and isolation of T. gondii by bioassay is described and emphasized on the importance of this route of transmission that caused lamb losses and an increase in possible sources of infection for human and environment.

Materials and methods

Flock description

The farm was located in a village in Chenaran, Khorasan Razavi province, Iran. Before the outbreak, the flock consisted of 250 sheep (240 ewes and 10 rams). The sheep were fed mainly by natural grazing. The farm was first visited in January 2011, just one month after the first abortion had occurred. During one month (from December 2010 to January 2011) 65 lambs were aborted, 12 lambs were born weak and 4 of them died 4 to 5 days after birth. Eight lambs were too weak and with motion disabilities. All aborted fetuses were aborted at late pregnancy period (>120 days). There had been no history of abortion in this flock before.

Sample collection

First four aborted fetuses were submitted to the Center of Excellence in Ruminant Abortion and Neonatal Mortality, School of Veterinary Medicine, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Iran in November 2010. The next samples consisted of live lambs, ewes and rams blood and the peritoneal or cervical fluid of dead lambs which were collected after the first visit (the first week of January, 2011) and the second visit (the forth week of January, 2011) to the farm.

General status of each fetus such as freshness, autolysis, mummification and presence of macroscopic lesions in fetus and fetal membranes were examined and recorded. To estimate the conceptual age of the fetuses, crown-rump length was measured (Evans and Sack 1973).

Detection of abortion after macroscopic examination of aborted fetuses and the embryos that died after birth was done. Samples from brain, heart, spleen, liver, eye, lung, kidney and thoracic fluid (only from aborted fetuses) were collected. Those fetuses’ tissues were divided into two portions, half of them were collected in aseptic way, which was then stored at −20 °C for molecular analysis, and the other half were collected in 10 % formalin for pathological study. Furthermore, as a pilot study of the general status of Toxoplasma seroprevalence, serum of 18 sheep (10 ewes with abortion, 3 rams, 1 live lamb and 4 pregnant ewes) were collected at the first visit to the farm and the samples of remaining ewes and rams (232) were collected at the second visit or by the farmer.

Bloods, peritoneal and cervical fluids were collected in sterile tubes before submitting to the Center of Excellence in Ruminant Abortion and Neonatal Mortality. The most important problem was that the farm was too far from the Center, so the farmer couldn’t transfer all samples immediately and most of them frosted or were not good for pathological study (65 samples) but the farmer was taught how to collect the fetal thoracic fluids of aborted fetuses in the first visit. The sera and fetal thoracic fluids were stored at −20 °C to be assayed by the indirect fluorescent antibody test (IFAT).

IFAT on maternal sera and fetal thoracic fluid

The presence of Toxoplasma antibodies in maternal serum and fetal thoracic fluid was assessed by IFAT, cut-off titer 1:20, as previously described by Razmi et al. (2010).

Histopathological examination

For the histopathological study, different sections of brain, liver, spleen, lung, heart, cotyledons or embryonic membranes (if existed) and kidney were trimmed and embedded in paraffin wax using routine procedures. From each block two Sects. 5 μm thick were cut, deparaffinized, rehydrated and stained with hematoxylin-eosin as described by Soleimani Rad (2009) and observed by light microscopy.

Bioassay

Isolation of T. gondii from aborted ovine fetuses, fetal membranes and placenta is best made by inoculation of laboratory mice. The best tissues for inoculation are fetal brain and placental cotyledons (Buxton 2008). In this study only homogenization of four aborted ovine fetuses’ brain (no placenta available) were done in an equal volume of normal saline with added antibiotics (100 international units (IU/ml) penicillin and 745 IU/ml streptomycin) in a blender. 0.5 ml of this mixture was inoculated to 5 Toxoplasma-free mice intraperitoneally. Two weeks after inoculation, their sera (collected by tail bleeding method) would be investigated by IFAT. If the results turned out to positive, they would be kept for 4–6 weeks more and then killed. The brains would be removed and examined by direct smear and Giemsa staining method for cyst detection.

Results

Sixty-nine out of 240 pregnant ewes (28.75 %) lost their fetuses or lambs in the flock during one month and all of them involved single lamb, 65 ewes aborted at late pregnancy (>120 days) and four of them did not abort but their lambs died 4–5 days after birth with a nervous dysfunction symptoms such as motion disabilities, convulsion and milk sucking problems. Abortion prevalence was estimated 23–34 % with 95 % confidence interval.

Macroscopic lesions

Brain congestion was dominant in 4 lambs that were born weak and died 4–5 days after birth. No gross lesions were seen in the aborted fetuses. There were 10 live lambs in the flock in the first visit showing weakness, gum congestion and motion disabilities, some of which may be a result of concurrent diseases such as vitamin E and selenium deficiency knowing the fact that the farm veterinarian had already prescribed Vitamin E and selenium supplement for the flock.

History and IFAT

Fifteen out of 18 samples taken at the first visit to the farm were positive, 2 ewes and 1 ram were negative. The remaining (226 samples of ewes, 7 samples of rams and 76 samples of aborted or alive lambs) were tested after the second visit. All of the IFAT results are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

IFAT positive and negative samples (cut-off titer 1:20)

| Positive (%) | Negative (%) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ewe | 71 (29.6) | 169 (70.4) | 240 |

| Ram | 2 (20) | 8 (80) | 10 |

| Lamb | 75 (97.4) | 2 (2.6) | 77 |

Table 2.

IFAT titration in positive samples

| 1:20 | 1:40 | 1:80 | 1:160 | 1:320 | 1:640 | 1:1,280 | 1:2,560 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ewe | 2 | 1 | – | 7 | 11 | 18 | 29 | 3 |

| Ram | 1 | – | 1 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Lamb | 31 | 12 | 18 | 11 | 3 | – | – | – |

| Total (%) | 34/148 (23) | 13/148 (8.8) | 19/148 (12.8) | 18/148 (12.2) | 14/148 (9.4) | 18/148 (12.2) | 29/148 (19.6) | 3/148 (2) |

All of the 65 aborted fetuses had IFAT positive mothers. The 6 remaining positive maternal serology related to the lambs were born and took colostrums, so the serology in these cases could not confirm the congenital infection and subsequently more tests needed to be conducted.

There wasn’t any similar disease in the village flocks in spite of using the same pastures in turn. In the history of this flock, there was a grazing very far from pasture in the central part of the Khorasan Razavi, where none of other flocks had ever been grazed.

Histopathology

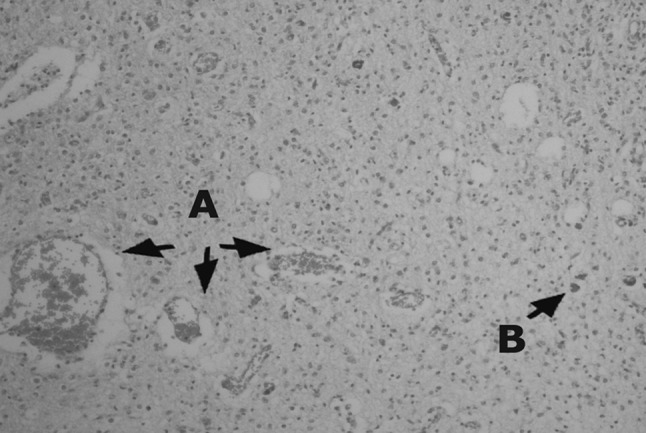

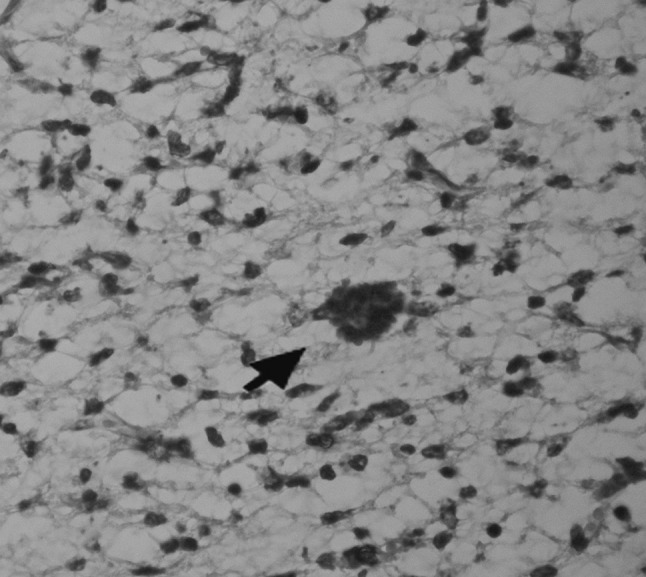

Because of the long distance between the village and the Center of Excellence in Ruminant Abortion and Neonatal Mortality (as described above), long procedures and high expenses, histopathology was done on four samples which were the dead lambs of the flock. The results were as follows: in liver congestion and fibrosis (1 sample), congestion (2 samples), congestion and bile hyperemia (1 sample). In lung hyperemia (3 samples), PM (postmortem autolysis) (1 sample), aspiration pneumonia (1 sample). Heart normal. In kidney congestion and degenerative changes (1 sample), hemorrhage (1 sample), PM (2 samples), In the brain most of the findings were similar to what had been recorded in Rassouli et al. (2013) such as; severe hyperemia, hemorrhage, edema (2 samples, Figs. 1, 2), different ischemic cell change, myelin degeneration (1 sample) but T. gondii tissue cysts were observed in 2 brain samples for the first time in this outbreak case (Figs. 2, 3).

Fig. 1.

Brain tissue: severe hemorrhage, stained by H&E. 10×

Fig. 2.

Brain tissue: a edema and hyperemia, b Toxoplasma gondii tissue cyst. Stained by H&E. 20×

Fig. 3.

Toxoplasma gondii tissue cyst. Stained by H&E. 40×

Bioassay

Two weeks after infected homogenate brains inoculation to mice, they were seropositive and cysts were seen after 8 weeks of inoculation by direct smear.

Discussion

Toxoplasma gondii has been recognized as one of the main causes of infective ovine abortion in New Zealand, Australia, UK, Norway and USA (Dubey and Beattie 1988) and 10–20 % of fetal losses are associated with this parasite but occasionally even much higher rate of fetal losses are observed (Blewett and Watson 1983). Clinical outbreaks associated with T. gondii typically occur in flocks in which Toxoplasma abortion has not been recorded in the recent past (Blewett and Watson 1983). It has been reported that 7–32 % of ovine abortion outbreaks in New Zealand from 1973 to 1989 were caused by T. gondii with higher rates in 1980s (Orr 1989; Gumbrell 1990; Dubey 2009). Also recently the ovine abortion storm was reported in the United States of America by Edwards and Dubey (2013).

If the infection occurs early in gestation, when the fetal immune system is relatively immature, fetal death is likely to occur. Infection at mid-gestation can result in birth of a stillborn or weak lamb which may have an accompanying small mummified fetus, whereas infection in later gestation may result in birth of a live, clinically normal, but infected lamb (Buxton 1990; Innes et al. 2009). We proposed that the occurrence of the disease (exposure to T. gondii), which took place in October 2010, was the reason of the death of the lambs 4–5 days after birth. The ewes which were in late gestation in this month, did give birth to their lambs but they died shortly after birth and the ewes which were in mid-gestation in this month, aborted their fetuses. So the first dead lamb was seen in November and the first abortion was witnessed in January.

Toxoplasmosis has been widely studied due to its importance to public health. There are a lot of unclear aspects of its congenital importance. According to the results of the recent researches in the UK, Toxoplasma vertical transmission can occur more frequently than what was previously thought (Duncanson et al. 2001; Morely et al. 2005, 2007; Hide et al. 2009; Innes et al. 2009; Dubey 2009), but Edwards and Dubey (2013) reported that this problem is resolved in the involved flock after one year or two years. If this kind of abortion takes place, it needs to be dealt with either by taking prophylactic measures or culling infected sheep from the flock which is more economical.

Serological positivity in aborted lambs can confirm the cause of abortion but in live lambs, which took colostrum, other tests such as histopathology and bioassay should be conducted. In this flock, Because of the natural grazing, they were in the pasture all day especially during abortion. Unfortunately the placenta could not be found by shepherd in any of the cases and consequently there were no placental cotyledons at our disposal for further examination.

Sheep is a source of meat widely consumed by human beings and if infected can cause serious issue concerning public health problems. Abortion products are often eaten up by wild predators or domestic animals especially in extensive farming style in which grazing animals may remain out of control for a long time, so these products can not be seen and collected. This leads to the spread of the infection to the other parts of the pasture. Infected birds and rodents can be ingested by cats and leading to excretion of large numbers of environmentally resistant T. gondii oocysts and the T. gondii life cycle completion (Zedda et al. 2010).

The ovine abortion estimated 23–34 % with 95 % confidence interval in this case has already caused $10,000 economical loss during one month. In this case, dead lambs, which carried viable T. gondii tissue cysts, being seen by histopathological procedures and multiplied in mice, served as the source of T. gondii infection for wildlife and domestic animals.

Iranians are accustomed to eating well cooked meat but subclinically infected rams and ewes serve as a source of infection for human beings. If the meat, liver and brain—mostly used products—of these infected animals are used undercooked or rarely raw, can be potentially infective for human and may lead to abortion in non-immune pregnant women.

References

- Blewett DA, Watson WA. The epidemiology of ovine toxoplasmosis. II. Possible sources of infection in outbreaks of clinical disease. British Vet J. 1983;139:546–555. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1935(17)30342-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton D. Ovine toxoplasmosis: a review. J Royal Soc Med. 1990;83:509–511. doi: 10.1177/014107689008300813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton D. Toxoplasmosis. In: Martin WB, Aitken ID, editors. Diseases of sheep. 2. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1991. pp. 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Buxton D (2008) Toxoplasmosis. OIE terrestrial manual. Vol 2, Chapter 2.9.10. CABI Publishing, Oxon, p 1284–1293

- Dubey JP. Toxoplasmosis in sheep-the last 20 years. Vet Parasitol. 2009;163:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey JP, Beattie CP. Toxoplasmosis in animals and man. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1988. p. 220. [Google Scholar]

- Duncanson P, Terry RS, Smith JE, Hide G. High levels of congenital transmission of Toxoplasma gondii in a commercial sheep flock. Int J Parasitol. 2001;31:1699–1703. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(01)00282-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JF, Dubey JP. Toxoplasma gondii abortion storm in sheep on a Texas farm and isolation of mouse virulent atypical genotype T. gondii from an aborted lamb from a chronically infected ewe. Vet Parasitol. 2013;192:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans HE, Sack WO. Prenatal development of domestic and laboratory mammals: growth curves, external features and selected references. Anat Histol Embryol. 1973;2:11–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0264.1973.tb00253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumbrell RC. Sheep abortion in New Zealand: 1989. Surveillance. 1990;17:22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley WJ, Jebson JL, McFarlan D. New Zealand type II abortion in ewes. Aust Vet J. 1954;30:21–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1954.tb08204.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hide G, Morely EK, Hughes JM, Gerwash OM, Elmahaishi S, Elmahaishi KH, Thomasson D, Wright EA, Williams RH, Murphy RG, Smith JE. Evidence for high levels of vertical transmission in Toxoplasma gondii. Parasitol. 2009;136:1877–1885. doi: 10.1017/S0031182009990941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innes EA, Barley PM, Buxton D, Katzer F. Ovin toxoplasmosis. Parasitol. 2009;136:1887–1894. doi: 10.1017/S0031182009991636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morely EK, Williams RH, Hughes JM, Terry RS, Duncanson P, Smith JE, Hide G. Significant familial differences in the frequency of abortion and Toxoplasma gondii infection within a flock of Charollais sheep. Parasitol. 2005;131:1–5. doi: 10.1017/S0031182004007127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morely EK, Williams RH, Hughes JM, Thomasson D, Terry RS, Duncanson P, Smith JE, Hide G. Evidence that primary infection of Charollais sheep with Toxoplasma gondii may not prevent fetal infection and abortion in subsequent lambings. Parasitol. 2007;135:169–173. doi: 10.1017/S0031182007003721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr MB. Sheep abortions-in Vermay 1988. Surveillance. 1989;16:24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Mora LM, Gottstein B, Conraths FG, Buxton D, editors. Protozoal abortion in farm ruminants, guidelines for diagnosis and control. Oxon: CABI publishing; 2007. pp. 122–210. [Google Scholar]

- Plant JW, Beh KJ, Acland HM. Laboratory findings from ovine abortion and perinatal mortality. Aust Vet J. 1972;48:558–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1972.tb08011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rassouli M, Razmi GR, Movassaghi AR, Bassami MR, Sami M. Pathological description and immunohistochemical demonstration of ovine abortion associated with Toxoplasma gondii in Iran. Korean J Vet Res. 2013;53:1–5. doi: 10.14405/kjvr.2013.53.1.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Razmi GR, Ghezi K, Mahouti A, Naseri Z. A serological study and subsequent isolation of Toxoplasma gondii from aborted ovine fetuses in Mashhad area, Iran. J Parasitol. 2010;96:15–17. doi: 10.1645/GE-2428.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skjerve E, Waldeland H, Nesbakken T, Kapperud G. Risk factors for the presence of antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii in Norwegian slaughter lambs. Prev Vet Med. 1998;35:219–227. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5877(98)00057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soleimani Rad J. Histology. 3. Tehran: Golban Medical Publications; 2009. pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zedda MT, Rolesu S, Pau S, Rosati I, Ledda S, Satta G, Patta C, Masala G. Epidemiological study of Toxoplasma gondii infection in ovine breeding. Zoonoses Public Health. 2010;57:102–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2009.01292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]