Abstract

Background:

The purpose of this randomised phase III trial was to evaluate whether the addition of simvastatin, a synthetic 3-hydroxy-3methyglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitor, to XELIRI/FOLFIRI chemotherapy regimens confers a clinical benefit to patients with previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer.

Methods:

We undertook a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial of 269 patients previously treated for metastatic colorectal cancer and enrolled in 5 centres in South Korea. Patients were randomly assigned (1 : 1) to one of the following groups: FOLFIRI/XELIRI plus simvastatin (40 mg) or FOLFIRI/XELIRI plus placebo. The FOLFIRI regimen consisted of irinotecan at 180 mg m−2 as a 90-min infusion, leucovorin at 200 mg m−2 as a 2-h infusion, and a bolus injection of 5-FU 400 mg m−2 followed by a 46-h continuous infusion of 5-FU at 2400 mg m−2. The XELIRI regimen consisted of irinotecan at 250 mg m−2 as a 90-min infusion with capecitabine 1000 mg m−2 twice daily for 14 days. The primary end point was progression-free survival (PFS). Secondary end points included response rate, duration of response, overall survival (OS), time to progression, and toxicity.

Results:

Between April 2010 and July 2013, 269 patients were enrolled and assigned to treatment groups (134 simvastatin, 135 placebo). The median PFS was 5.9 months (95% CI, 4.5–7.3) in the XELIRI/FOLFIRI plus simvastatin group and 7.0 months (95% CI, 5.4–8.6) in the XELIRI/FOLFIRI plus placebo group (P=0.937). No significant difference was observed between the two groups with respect to OS (median, 15.9 months (simvastatin) vs 19.9 months (placebo), P=0.826). Grade ⩾3 nausea and anorexia were noted slightly more often in patients in the simvastatin arm compared with with the placebo arm (4.5% vs 0.7%, 3.0% vs 0%, respectively).

Conclusions:

The addition of 40 mg simvastatin to the XELIRI/FOLFIRI regimens did not improve PFS in patients with previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer nor did it increase toxicity.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, simvastatin, XELIRI/FOLFIRI chemotherapy

Statins are commonly prescribed medications that lower serum cholesterol and decrease cardiovascular morbidity and mortality and exhibit a favourable safety profile. Statins are potent synthetic inhibitors of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase, which is the rate-limiting enzyme of the mevalonate pathway. Mevalonate-derived prenyl groups, farnesyl pyrophosphate, and geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate, facilitate essential intracellular functions of various proteins, such as Ras and Ras homologue (Rho) (Goldstein and Brown, 1990; Casey, 1995; Rando, 1996). Ras and Rho have important roles in intracellular signal transduction pathways responsible for cell growth, proliferation, migration, and survival (Casey, 1995). Statins are known to affect the posttranscriptional modifications of Ras and Rho; the antitumour effect of statins has been suggested in various cancer cell lines (Lee et al, 2006).

Previous epidemiological studies have demonstrated that statins may exert beneficial effects in addition to their established lipid-lowering effects. Specifically, statin treatment was shown to confer a 47% relative reduction in the risk of colorectal cancer after adjustment for other known risk factors (Poynter et al, 2005) and an overall risk reduction of cancer of 20% (Graaf et al, 2004). Recently, a large population-based colorectal cancer cohort study found that statin use after the diagnosis of colorectal cancer was associated with reduced colorectal cancer-specific mortality (adjusted HR 0.71; 95% CI, 0.61–0.84) and all-cause mortality (adjusted HR 0.75; 95% CI, 0.66–0.84) (Cardwell et al, 2014).

Statins have been shown to exert their anticancer effects by inhibiting endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and the induction of apoptosis. Although most studies demonstrating an antitumour effect have used high statin concentrations that are not feasible for human use (Thibault et al, 1996; Larner et al, 1998; Kim et al, 2001), we suggested an antitumour effect of simvastatin using a dose level that is equivalent to the accepted cardiovascular therapeutic dose level in humans without additive adverse effects (Lee et al, 2009, 2011).

We previously reported a phase II study in which simvastatin treatment in combination with FOLFIRI chemotherapy was found to be effective and feasible in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (Lee et al, 2009). Therefore, the present randomised phase III trial was conducted to assess the efficacy and safety of the addition of simvastatin to XELIRI or FOLFIRI chemotherapy in patients with unresectable advanced or metastatic, previously treated colorectal cancer.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

This study was a multi-centre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised phase III trial of patients aged ⩾19 years with histologically confirmed metastatic (stage IV) colorectal adenocarcinoma. All patients had received one prior oxaliplatin-containing chemotherapy treatment. Eligible patients had Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of two or less and exhibited measurable disease based on the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) criteria, version 1.1. Patients were required to have adequate function of all major organs (including renal, hepatic, and bone marrow, defined as an absolute neutrophil count ⩾1500 μl−1, an Hb level ⩾9 g dl−1, and a platelet count ⩾100 000 μl−1, respectively). Patients with severe co-morbid illnesses and/or active infections as well as pregnant or lactating women were excluded. Also excluded were patients with CNS metastatic disease and obvious peritoneal seeding or a bowel obstruction disturbing oral intake. Patients who had prior history of another malignancy within 5 years of study, with the exception of basal cell carcinoma of the skin or carcinoma in situ of the uterine cervix, were excluded. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient before entry into the study. The protocol was approved at each participating site by an institutional review board. This trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov as number NCT01238094.

Randomisation and treatment

Eligible patients were randomised to receive (1 : 1) XELIRI/FOLFIRI chemotherapy plus simvastatin or XELIRI/FOLFIRI chemotherapy plus placebo until confirmation of disease progression. Randomisation was carried out centrally with the minimisation method (Sorbye et al, 2007), with stratification by the presence of measurable disease. Eligible patients received one of the following chemotherapy regimens: (1) 3-week cycles of 250 mg m−2 irinotecan intravenously on day 1 plus capecitabine (1000 mg m−2) twice a day orally from days 1 to 14 (XELIRI); or (2) 2-week cycles of irinotecan (180 mg) diluted in 500 ml 5% dextrose as a 90-min infusion, followed by leucovorin (200 mg m−2) in a 2-h infusion, a bolus injection of 5-FU (400 mg m−2) and finally a 46-h continuous infusion of 5-FU (2400 mg m−2) (FOLFIRI). The choice of chemotherapy regimen was left to the investigator's discretion. The simvastatin or placebo tablet (40 mg) was administered orally once per day every day during the period of chemotherapy, without rest. Simvastatin and placebo administration was stopped upon termination of XELIRI/FOLFIRI chemotherapy. Treatment cycles were repeated until evidence of disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or patient refusal.

Assessments

The primary end point of the study was progression-free survival (PFS), defined as the time from the date of the first study treatment to the date of disease progression or death from any cause. Secondary end points included response rate, duration of tumour response, overall survival (OS), time to progression (TTP), and safety profile. OS was defined as the time from the date of treatment to the date of death. TTP was defined as the interval between the date of the first study treatment and the date of disease progression, not including deaths from causes other than disease progression. Duration of tumour response was defined as the interval between the date of the first observation of response (CR or PR) in patients who demonstrated a durable response (confirmed response) and the date of disease progression.

In the pretreatment evaluation, a patient's history was taken and a physical examination was performed. The examination consisted of a complete blood cell count with differentials, chemistry, creatinine phophokinase (CPK) and LDH measurements, lipid profiling, a chest X-ray, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis, and any other clinically indicated diagnostic procedures. Before each treatment cycle, a physical examination was performed, vital signs were recorded, and laboratory tests were performed. Radiological assessments, including contrast-enhanced abdominal and pelvis CT scans, were completed at baseline and every 6 weeks thereafter for disease evaluation according to the RECIST (version 1.1) criteria (Eisenhauer et al, 2009). Once disease progression was documented, patients were followed for survival status every 2 months until death.

Safety assessments were conducted until 21 days after the last dose of study treatment. Adverse effects were graded and monitored in accordance with the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE, version 3.0).

Statistical analysis

The intent-to-treat population included all recruited subjects who received any study medication. The safety population included all randomly assigned patients who received at least one dose of study treatment. Assuming a median PFS of 3 months for the placebo group and 4.5 months for the simvastatin maintenance group (i.e., assuming a 50% improvement in the PFS), this study required a total of 268 patients (134 per arm) to have 90% power to detect a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.67 by the two-sided log-rank test with an alpha value of 0.05. The objective response rate and patient's clinical characteristics were evaluated using Fisher's exact test for categorical variables. For OS, PFS, and TTP, survival functions were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method and were compared between different groups using the log-rank test. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All reported P-values are two-sided and were calculated using the SPSS version 21 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Patients

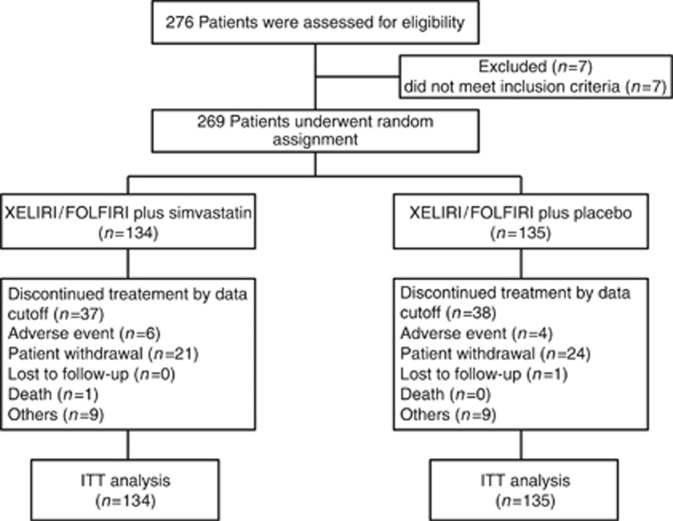

Between April 2010 and July 2013, 269 patients were enrolled and randomly assigned to receive either simvastatin (n=134) or placebo (n=135), in combination with XELIRI/FOLFIRI, at one of the five centres in Korea (Figure 1). The demographic and baseline characteristics were generally well balanced between the two treatment groups (Table 1). At data cutoff (30 September 2014), 189 progression events and 165 deaths had occurred.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram of the study design and participants.

Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics.

|

XELIRI or FOLFIRI plus |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Simvastatin 40 mg (n=134) |

Placebo 40 mg (n=135) |

|||

| Characteristics | No. | % | No. | % |

|

Age, years | ||||

| Mean±s.d. | 57.2±9.41 | 57.1±9.75 | ||

| Range | 32–79 |

35–82 |

||

|

Gender | ||||

| Male | 78 | 58.2 | 91 | 67.4 |

| Female | 56 | 41.8 | 44 | 32.6 |

|

ECOG performance status | ||||

| 0 | 21 | 15.7 | 33 | 24.4 |

| 1 | 111 | 82.8 | 100 | 74.1 |

| 2 | 2 | 1.5 | 2 | 1.5 |

|

Type of cancer | ||||

| Colon | 78 | 58.2 | 83 | 61.5 |

| Rectum | 56 | 41.8 | 52 | 38.5 |

|

Previous chemotherapy | ||||

| XELOX/FOLFOX | 115 | 85.8 | 115 | 85.2 |

| Oxaliplatin+TS-1 | 3 | 2.2. | 2 | 1.5 |

| XELOX+Cediranib | 2 | 1.5 | ||

| FOLFOX+Cetuximab | 3 | 2.2 | 5 | 3.7 |

| XELOX/FOLFOX+bevacizumab | 5 | 3.7 | 6 | 4.4 |

| Others | 5 | 3.7 | 6 | 4.4 |

|

Number of metastatic sites | ||||

| 1 | 60 | 44.8 | 56 | 41.5 |

| 2 | 46 | 34.3 | 56 | 41.5 |

| 3 | 22 | 16.4 | 17 | 12.6 |

| ⩾4 | 5 | 3.7 | 4 | 3.0 |

|

Metastasis sites | ||||

| Liver | 80 | 59.7 | 85 | 63.0 |

| Lung | 68 | 50.7 | 52 | 38.5 |

| Intra-abdominal lymph nodes | 36 | 26.9 | 38 | 28.1 |

| Peritoneal seeding | 25 | 18.7 | 27 | 20.0 |

| Cervical lymph nodes | 3 | 2.2 | 6 | 4.4 |

| Bone | 5 | 3.7 | 4 | 3.0 |

|

Chemotherapy regimen | ||||

| FOLFIRI | 90 | 67.2 | 90 | 67.2 |

| XELIRI | 44 | 32.8 | 44 | 32.8 |

Abbreviations: ECOG=Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; FOLFIRI=fluorouracil/leucovorin/irinotecan; FOLFOX=fluorouracil/leucovorin/oxaliplatin; XELIRI=capecitabine/irinotecan; XELOX=capecitabine/oxaliplatin.

Efficacy

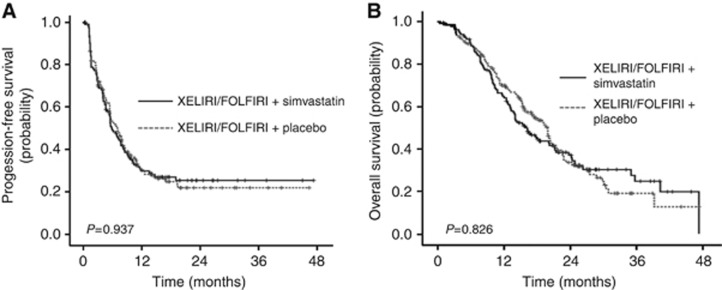

The median PFS, the primary end point in this study, was 5.9 months (95% confidence interval (CI), 4.5–7.3 months) in the simvastatin group and 7.0 months (95% CI, 5.4–8.6) in the placebo group (HR, 1.026; 95% CI, 0.77–1.37, P=0.858) (Figure 2A). No significant differences were observed between the simvastatin and placebo groups regarding two of the secondary end points, OS and TTP. Specifically, the median OS was 15.3 months (95% CI, 12.1–18.5) in the simvastatin arm and 19.2 months (95% CI, 16.8–21.6) in the placebo arm (Figure 2B). The median TTP was 5.9 months in the simvastatin group and 7.0 months in the placebo group. The ORR (overall response rate) was 11.9% in the simvastatin group and 11.8% in the placebo group; the DCR (disease control rate) was 67.2% and 71.1%, respectively. No significant difference in response rate was observed between the two treatment arms (P=1.00 for ORR, P=0.511 for DCR, Table 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves of PFS and OS. (A) Kaplan–Meier curves of progression-free survival for patients who received simvastatin 40 mg plus XELIRI/FOLFIRI or placebo plus XELIRI/FOLFIRI (median PFS: 5.9 months in the XELIRI/FOLFIRI plus simvastatin group vs 7.0 months in the XELIRI/FOLFIRI plus placebo group) (B) Kaplan–Meier curves of OS of all patients according to treatment arms (median OS: 15.3 months in the XELIRI/FOLFIRI plus simvastatin group vs 19.2 months in the XELIRI/FOLFIRI plus placebo group).

Table 2. Best objective response by RECIST version 1.1.

|

Simvastatin 40 mg (n=134) |

Placebo 40 mg (n=135) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response | No. | % | No. | % |

|

Responders | ||||

| Complete response | 2 | 1.5 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Partial response | 14 | 10.4 | 15 | 11.1 |

| Stable disease | 74 | 55.2 | 80 | 59.3 |

| Progressive disease | 30 | 22.4 | 24 | 17.8 |

| Nonevaluable | 14 | 10.4 | 15 | 11.1 |

| Overall response rate (ORR) | 16 | 11.9 | 16 | 11.8 |

| Disease control rate (DCR) | 90 | 67.2 | 96 | 71.1 |

Abbreviation: RECIST=Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors.

Toxicity

All patients enrolled were monitored for adverse effects. The overall incidence of grade ⩾3 adverse events (AEs) was 48.5% (65 out of 134 patients) in the simvastatin group and 45.9% (62 out of 135 patients) in the placebo group (Table 3). The most common AEs experienced in both treatment arms were anaemia, nausea, anorexia, and alopecia; the most common grade ⩾3 AEs were neutropenia (29.1%, simvastatin plus XELIRI/FOLFIRI; 28.9%, placebo plus XELRIRI/FOLFIRI), anaemia (9.0% vs 10.4%, respectively), and diarrhoea (7.5% vs 6.0%, respectively). The addition of simvastatin did not result in any clinically significant increase in treatment-related toxicities. No patient experienced a grade 3 or 4 increase of CPK, a finding that might be due to the use of simvastatin. The proportion of patients having any grade of liver enzyme elevation was slightly higher in the simvastatin group (40.3% vs 34.3% for aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 29.8% vs 22.2% for alanine aminotransferase (ALT)), although this difference was not significant. Abnormal elevations of CPK, ALT, and AST were eventually normalised with supportive management.

Table 3. Toxicity profile.

|

Simvastatin (n=134) |

Placebo (n=135) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

NCI-CTC grade (%) |

NCI-CTC grade (%) |

|||

| Toxicity | Any grade | G3–4 | Any grade | G3–4 |

|

Haematological | ||||

| Neutropenia | 106 (79.1) | 39 (29.1) | 101 (74.8) | 39 (28.9) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 3 (2.2) | 3 (2.2) | 5 (3.7) | 5 (3.7) |

| Anaemia | 118 (88.1) | 12 (9.0) | 120 (88.9) | 14 (10.4) |

| Leukopenia | 66 (49.3) | — | 69 (51.1) | — |

| Thrombocytopenia | 72 (53.7) | 5 (3.7) | 62 (45.9) | 6 (4.4) |

|

Non-haematological | ||||

| Nausea | 121 (90.3) | 6 (4.5) | 120 (88.9) | 1 (0.7) |

| Vomiting | 68 (50.7) | 7 (5.2) | 77 (57.0) | 7 (5.2) |

| Diarrhoea | 96 (71.6) | 10 (7.5) | 96 (71.1) | 8 (6.0) |

| Constipation | 77 (57.5) | — | 81 (60.0). | — |

| Stomatitis | 14 (10.4) | — | 6 (4.5) | — |

| Mucositis | 94 (70.1) | — | 88 (65.2) | — |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 112 (83.6) | 3 (2.2) | 110 (81.5) | — |

| Alopecia | 116 (86.6) | — | 119 (88.1) | — |

| Fever | 13 (1.0) | — | 13 (9.7) | — |

| Anorexia | 111 (82.8) | 4 (3.0) | 105 (77.8) | — |

| Pruritus | 23 (17.2) | — | 19 (14.1) | — |

| Hand–foot syndrome | 51 (38.1) | — | 47 (34.8) | — |

| Fatigue | 87 (64.9) | — | 98 (72.6) | — |

| Insomnia | 41 (30.6) | — | 33 (24.4) | — |

| Hyperpigmentation | 101 (75.4) | — | 104 (77.0) | — |

| Skin rash | 64 (47.8) | — | 63 (45.9) | — |

| Elevated AST | 54 (40.3) | 3 (2.2) | 46 (34.1) | 1 (0.7) |

| Elevated ALT | 40 (29.9) | — | 30 (22.2) | 2 (1.5) |

| Elevated CPK | 11 (8.2) | — | 10 (7.4) | — |

Abbreviations: ALT=alanine aminotransferase; AST=aspartate aminotransferase; CPK=creatinine phophokinase; NCI-CTC=National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria.

Treatment and drug delivery

The median number of chemotherapy cycles administered was 6 (1–36) in the simvastatin group and 7 (1–37) in the placebo group. The delivered relative dose intensities for irinotecan, capecitabine, fluorouracil, leucovorin, and simvastatin were similarly high in both treatment groups (Supplementary Table S1). Reductions in the dose of randomly assigned treatment were carried out for 56.7% of all patients in the simvastatin group and 56.0% in the placebo group, whereas 27% of all patients in the simvastatin group and 24% in the placebo group experienced delays in randomly assigned treatment.

Subgroup analysis

We analysed differences of survival outcomes between subgroups according to various baseline characteristics, including sex, age, performance status, prior treatment (surgery or chemotherapy), measurable disease, liver metastasis, lung metastasis, peritoneal seeding, and chemotherapy regimen (XELIRI or FOLFIRI). No significant differences were observed by subgroup analysis between the two treatment groups for either PFS or OS (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). Specifically, the 95% CI upper limit was >1 for all subgroup comparisons. Unexpectedly, the median PFS was significantly longer in patients treated with XELIRI±simvastatin compared with those who were treated with FOLFIRI±simvastatin (8.4 months vs 5.6 months, P=0.011). The multivariate analysis with respect to PFS revealed that chemotherapy regimen (FOLFIRI), absence of prior radiotherapy, presence of liver metastasis, and presence of cervical lymph node metastasis were associated with a worse PFS (Supplementary Table S4). The median OS was not significantly different between the two chemotherapy regimens.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first randomised, placebo-controlled, phase III study to evaluate the antitumour activity of an HMG CoA reductase inhibitor, simvastatin, in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy against pretreated metastatic colorectal cancer. This study did not yield in superior outcome of simvastatin plus XELIRI/FOLFIRI over XELIRI/FOLFIRI chemotherapy alone in terms of PFS. The addition of a low dose of simvastatin, equivalent to the cardiovascular therapeutic dose, did not increase the toxicity of the conventional XELIRI or FOLFIRI chemotherapy regimens.

The median PFS in this study was relatively high. When the study was designed in 2009, the PFS of 3 months was anticipated by second-line irinotecan-based regimens, which was predicted on the available scientific literature at the time (Fuchs et al, 2003; Lal et al, 2004). In our study, the median PFS was 5.9 months in the simvastatin group and 7.0 months in the placebo group. Moreover, there was a significant improvement in PFS with XELIRI vs FOLFIRI regardless of simvastatin (HR, 0.666; 95% CI, 0.49–0.92, P=0.012).

One other possible explanation for the lack of effect of statins is that a low dose of simvastatin (40 mg) may not have been sufficient to control tumour cell proliferation. Although most studies investigating the potential anticancer effects of statins have used high serum concentrations of statin (2–20 μM via the administration of 20–200 mg kg−1; Mantha et al, 2005; Dai et al, 2007; Park et al, 2010), these high doses are not feasible for human use. In addition, low concentrations of statins (equivalent to the cardiovascular protective dose) have shown promising antitumour efficacy (Dulak and Jozkowicz, 2005; Lee et al, 2011). Moreover, a similarly low concentration of simvastatin when given in combination with bevacizumab has been shown to indirectly block the invasion of human umbilical vein endothelial cells by suppressing angiogenesis-related mediators (Lee et al, 2014).

However, given that low dose of simvastatin (40 mg) used in the current study might have been insufficient to achieve the concentration range with the anticancer effect, further studies are needed to investigate whether higher dose of simvastatin in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy, antiangiogenic therapy, or other targeted therapies are of clinical benefit. The effects of statins were found to depend on their blood concentration. At low concentrations (0.005–0.01 μM l−1) of statins, pro-angiogenic effects were rather enhanced and antiangiogenic effects at higher concentrations (⩾0.05–0.1 μM l−1) were associated with decreased endothelial release of vascular endothelial growth factor and increased endothelial apoptosis (Weis et al, 2002). To reach serum concentrations of 0.1–0.2 μM, simvastatin has to be administered at a dose of 1–2 mg kg−1 day−1, therefore we plan to investigate the clinical efficacy and safety with higher dose than 40 mg of simvastatin in combination with chemotherapy. At the present time, a prospective, single arm, phase II trial to evaluate the efficacy of simvastatin (80 mg) plus XELOX and bevacizumab in metastatic colorectal cancer is currently ongoing (NCT 02026583).

Numerous studies have investigated the relationships between statin use, colorectal cancer risk, and clinical outcomes in the settings of adjuvant, neo-adjuvant, or metastatic disease; however, the findings of these studies have been inconclusive (Ng et al, 2011; Cardwell et al, 2014; Hoffmeister et al, 2015). Relatively few studies have focussed on the effects of statins in advanced or metastatic cancers. Siddiqui et al (2009) reported that statin users had a 30% decreased prevalence of metastasis compared with statin non-users among patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer (odds ratio 0.7, 95% CI 0.4–0.9, P<0.01). Another study found that pretreatment of different colon cancer cell lines with lovastatin significantly increased apoptosis induced by 5-fluorouracil or cisplatin (Agarwal et al, 1999). Furthermore, our group conducted an open-label phase II trial evaluating the efficacy and toxicity profile of conventional FOLFIRI chemotherapy in combination with simvastatin in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer and found that this combination exhibited promising antitumour activity (Lee et al, 2009).

Among the 229 patients whose KRAS mutation status was known, 83 (36%) had tumours with a KRAS mutation in exon 2 (49 patients in the simvastatin group and 34 patients in the placebo group). The median PFSs in this subgroup were not significantly different between the two treatment groups. The median PFS was 5.4 months (95% CI, 1.9–8.9) in the simvastatin arm and 6.0 months (95% CI, 4.4–7.6) in the placebo arm (P=0.859). Similarly, the median OS was 13.7 months (95% CI, 11.8–15.6) in the simvastatin group and 14.5 months (95% CI, 10.8–18.1) in the placebo group (P=0.615; Supplementary Figure S1). This finding is consistent with a CAIRO2 study of combination chemotherapy with capeciatabine, oxaliplatin, and cetuximab in patients with KRAS mutations and metastatic colorectal cancer, in which the use of statins was not associated with an improved PFS (Krens et al, 2014). Our group previously reported that 0.2 μM simvastatin enhanced the antitumour activity of cetuximab in colorectal cancer cells carrying KRAS mutations (Lee et al, 2011). We hypothesised that statins overcome cetuximab resistance in KRAS mutant colorectal cancer cells by decreasing the stability and enzymatic activity of BRAF. However, the subgroup of patients with KRAS mutations was not large enough to evaluate whether simvastatin in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy confers a significant clinical benefit to patients with colorectal cancer and KRAS mutations. Based on these findings, biomarker-stratified prospective studies are needed to evaluate the efficacy of statins in combination with conventional chemotherapy in patients with KRAS mutations and colorectal cancer.

In conclusion, the PFS was not improved by adding low dose of simvastatin (40 mg) to XELIRI/FOLFIRI compared with XELIRI/FOLFIRI alone in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer in second-line setting. In the future, we hope further studies will be performed to investigate the efficient combination strategies involving statins and cytotoxic chemotherapy regimen with targeted therapy.

Acknowledgments

We thank all participating patients and their families, as well as the research nurses and study coordinators.

Author Contributions

WK Kang conceived and designed the study and supervised the research; SH Lim gathered and analysed the data and wrote the manuscript; TW Kim, YS Hong, SW Han, KH Lee, HJ Kang, IG Hwang, YS Park, and HY Lim reviewed and participated in the preparation of the manuscript; JY Lee, HS Kim, ST Kim, J Lee, and JO Park provided comments on the manuscript; and SH Jung provided comments on the statistical analysis.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website (http://www.nature.com/bjc)

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Material

References

- Agarwal B, Bhendwal S, Halmos B, Moss SF, Ramey WG, Holt PR (1999) Lovastatin augments apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutic agents in colon cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res 5: 2223–2229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardwell CR, Hicks BM, Hughes C, Murray LJ (2014) Statin use after colorectal cancer diagnosis and survival: a population-based cohort study. J Clin Oncol 32: 3177–3183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey PJ (1995) Protein lipidation in cell signaling. Science 268: 221–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y, Khanna P, Chen S, Pei XY, Dent P, Grant S (2007) Statins synergistically potentiate 7-hydroxystaurosporine (UCN-01) lethality in human leukemia and myeloma cells by disrupting Ras farnesylation and activation. Blood 109: 4415–4423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulak J, Jozkowicz A (2005) Anti-angiogenic and anti-inflammatory effects of statins: relevance to anti-cancer therapy. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 5: 579–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, Rubinstein L, Shankar L, Dodd L, Kaplan R, Lacombe D, Verweij J (2009) New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 45: 228–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs CS, Moore MR, Harker G, Villa L, Rinaldi D, Hecht JR (2003) Phase III comparison of two irinotecan dosing regimens in second-line therapy of metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 21: 807–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JL, Brown MS (1990) Regulation of the mevalonate pathway. Nature 343: 425–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graaf MR, Beiderbeck AB, Egberts AC, Richel DJ, Guchelaar HJ (2004) The risk of cancer in users of statins. J Clin Oncol 22: 2388–2394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmeister M, Jansen L, Rudolph A, Toth C, Kloor M, Roth W, Blaker H, Chang-Claude J, Brenner H (2015) Statin use and survival after colorectal cancer: the importance of comprehensive confounder adjustment. J Natl Cancer Inst 107: djv045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WS, Kim MM, Choi HJ, Yoon SS, Lee MH, Park K, Park CH, Kang WK (2001) Phase II study of high-dose lovastatin in patients with advanced gastric adenocarcinoma. Invest New Drugs 19: 81–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krens LL, Simkens LH, Baas JM, Koomen ER, Gelderblom H, Punt CJ, Guchelaar HJ (2014) Statin use is not associated with improved progression free survival in cetuximab treated KRAS mutant metastatic colorectal cancer patients: results from the CAIRO2 study. PLoS One 9: e112201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal R, Dickson J, Cunningham D, Chau I, Norman AR, Ross PJ, Topham C, Middleton G, Hill M, Oates J (2004) A randomized trial comparing defined-duration with continuous irinotecan until disease progression in fluoropyrimidine and thymidylate synthase inhibitor-resistant advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 22: 3023–3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larner J, Jane J, Laws E, Packer R, Myers C, Shaffrey M (1998) A phase I-II trial of lovastatin for anaplastic astrocytoma and glioblastoma multiforme. Am J Clin Oncol 21: 579–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Jung KH, Park YS, Ahn JB, Shin SJ, Im SA, Oh do Y, Shin DB, Kim TW, Lee N, Byun JH, Hong YS, Park JO, Park SH, Lim HY, Kang WK (2009) Simvastatin plus irinotecan, 5-fluorouracil, and leucovorin (FOLFIRI) as first-line chemotherapy in metastatic colorectal patients: a multicenter phase II study. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 64: 657–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Lee I, Han B, Park JO, Jang J, Park C, Kang WK (2011) Effect of simvastatin on cetuximab resistance in human colorectal cancer with KRAS mutations. J Natl Cancer Inst 103: 674–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Lee I, Park C, Kang WK (2006) Lovastatin-induced RhoA modulation and its effect on senescence in prostate cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 339: 748–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Lee I, Lee J, Park C, Kang WK (2014) Statins, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors, potentiate the anti-angiogenic effects of bevacizumab by suppressing angiopoietin2, BiP, and Hsp90alpha in human colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 111: 497–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantha AJ, Hanson JE, Goss G, Lagarde AE, Lorimer IA, Dimitroulakos J (2005) Targeting the mevalonate pathway inhibits the function of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Clin Cancer Res 11: 2398–2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng K, Ogino S, Meyerhardt JA, Chan JA, Chan AT, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, Saltz LB, Mayer RJ, Benson AB 3rd, Schaefer PL, Whittom R, Hantel A, Goldberg RM, Bertagnolli MM, Venook AP, Fuchs CS (2011) Relationship between statin use and colon cancer recurrence and survival: results from CALGB 89803. J Natl Cancer Inst 103: 1540–1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park IH, Kim JY, Jung JI, Han JY (2010) Lovastatin overcomes gefitinib resistance in human non-small cell lung cancer cells with K-Ras mutations. Invest New Drugs 28: 791–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poynter JN, Gruber SB, Higgins PD, Almog R, Bonner JD, Rennert HS, Low M, Greenson JK, Rennert G (2005) Statins and the risk of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 352: 2184–2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rando RR (1996) Chemical biology of isoprenylation/methylation. Biochem Soc Trans 24: 682–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui AA, Nazario H, Mahgoub A, Patel M, Cipher D, Spechler SJ (2009) For patients with colorectal cancer, the long-term use of statins is associated with better clinical outcomes. Dig Dis Sci 54: 1307–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorbye H, Kohne CH, Sargent DJ, Glimelius B (2007) Patient characteristics and stratification in medical treatment studies for metastatic colorectal cancer: a proposal for standardization of patient characteristic reporting and stratification. Ann Oncol 18: 1666–1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibault A, Samid D, Tompkins AC, Figg WD, Cooper MR, Hohl RJ, Trepel J, Liang B, Patronas N, Venzon DJ, Reed E, Myers CE (1996) Phase I study of lovastatin, an inhibitor of the mevalonate pathway, in patients with cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2: 483–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis M, Heeschen C, Glassford AJ, Cooke JP (2002) Statins have biphasic effects on angiogenesis. Circulation 105: 739–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.