Abstract

Objective

Lung injury activates multiple pro-inflammatory pathways, including neutrophils, epithelial, and endothelial injury, and coagulation factors leading to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Low-dose methylprednisolone therapy (MPT) improved oxygenation and ventilation in early pediatric ARDS without altering duration of mechanical ventilation or mortality. We evaluated the effects of MPT on biomarkers of endothelial [Ang-2 and soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (sICAM-1)] or epithelial [soluble receptor for activated glycation end products (sRAGE)] injury, neutrophil activation [matrix metalloproteinase-8 (MMP-8)], and coagulation (plasminogen activator inhibitor-1).

Design

Double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial.

Setting

Tertiary-care pediatric intensive care unit (ICU).

Patients

Mechanically ventilated children (0–18 years) with early ARDS.

Interventions

Blood samples were collected on days 0 (before MPT), 7, and 14 during low-dose MPT (n = 17) vs. placebo (n = 18) therapy. The MPT group received a 2-mg/kg loading dose followed by 1 mg/kg/day continuous infusions from days 1 to 7, tapered off over 7 days; placebo group received equivalent amounts of 0.9% saline. We analyzed plasma samples using a multiplex assay for five biomarkers of ARDS. Multiple regression models were constructed to predict associations between changes in biomarkers and the clinical outcomes reported earlier, including P/F ratio on days 8 and 9, plateau pressure on days 1 and 2, PaCO2 on days 2 and 3, racemic epinephrine following extubation, and supplemental oxygen at ICU discharge.

Results

No differences occurred in biomarker concentrations between the groups on day 0. On day 7, reduction in MMP-8 levels (p = 0.0016) occurred in the MPT group, whereas increases in sICAM-1 levels (p = 0.0005) occurred in the placebo group (no increases in sICAM-1 in the MPT group). sRAGE levels decreased in both MPT and placebo groups (p < 0.0001) from day 0 to day 7. On day 7, sRAGE levels were positively correlated with MPT group PaO2/FiO2 ratios on day 8 (r = 0.93, p = 0.024). O2 requirements at ICU transfer positively correlated with day 7 MMP-8 (r = 0.85, p = 0.016) and Ang-2 levels (r = 0.79, p = 0.036) in the placebo group and inversely correlated with day 7 sICAM-1 levels (r = −0.91, p = 0.005) in the MPT group.

Conclusion

Biomarkers selected from endothelial, epithelial, or intravascular factors can be correlated with clinical endpoints in pediatric ARDS. For example, MPT could reduce neutrophil activation (⇓MMP-8), decrease endothelial injury (⇔sICAM-1), and allow epithelial recovery (⇓sRAGE). Large ARDS clinical trials should develop similar frameworks.

Trial Registration

Keywords: ARDS, biomarker, pediatric, methylprednisolone, MMP-8, Ang-2, ICAM-1, sRAGE

Background

The pathogenesis of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) may result from dysregulated inflammation in the endothelial and epithelial spaces from pulmonary or systemic circulations (1). ARDS is associated with alveolar and interstitial edema, infiltration of inflammatory cells (neutrophils and macrophages) into the alveolar space due to vascular permeability, abnormal coagulation, and endothelial and alveolar epithelial injury (1). Corticosteroids may suppress this dysregulated inflammation in ARDS and thereby improve clinical outcomes (2). In adult patients with ARDS, early low-dose corticosteroid treatment showed promising results (3). However, the American College of Critical Care Medicine recommends the use of corticosteroids only for adult patients with moderate to severe ARDS resulting from community-acquired pneumonia (grade 2B). A single-center retrospective study reported that utilization of corticosteroids in pediatric ARDS was associated with worsening clinical outcomes (4). However, this study did not record the indications for corticosteroid administration and neither considered the length of therapy nor the need for tapering steroids to prevent rebound inflammation (5).

We published the first pilot randomized trial of low-dose methylprednisolone therapy (MPT) for early pediatric ARDS examining the feasibility of this therapy (6). We modified the protocol for administering MPT in adult ARDS (3), which includes the slow tapering of MPT dosage over 1 week to avoid rebound lung inflammation and systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) leading to recurrent respiratory failure (7). MPT therapy did not alter ventilator-free days or mortality but appeared to alter oxygenation and ventilation (6). We also examined different regulatory patterns of pro- and anti-inflammatory plasma cytokines in the MPT and placebo groups to identify several cytokines as potential predictors for alterations in clinical parameters of disease severity (8). Larger randomized controlled studies are warranted for investigating corticosteroid use in early pediatric ARDS.

Corticosteroids are widely used in pediatric patients with ARDS (4), but their effects on biomarker levels in ARDS remain unknown. We selected five plasma biomarkers signifying the endothelial [Ang-2 and soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (sICAM-1)], epithelial [soluble receptor for activated glycation end products (sRAGE)], coagulation [plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI-1)], and neutrophil [matrix metalloproteinase-8 (MMP-8)] factors contributing to the pathogenesis of ARDS. The main purpose of this pilot study was to generate a potential framework for studying ARDS pathogenesis in future clinical trials.

Materials and Methods

Clinical Trial

A double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial (https://clinicaltrial.gov, NCT01274260) was conducted in pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) in Le Bonheur children’s hospital in Memphis, TN, USA (6). The Institutional Review Board of University of Tennessee Health Science Center approved this study. Children (0–18 years) fulfilling the Berlin definition of ARDS and receiving mechanical ventilation were included in the study after informed consent. Patients receiving glucocorticoids chronically, terminally ill or in hospice care, immunosuppressed, with extensive burns, adrenal insufficiency, vasculitis, diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, invasive fungal infection, chronic liver disease or gastrointestinal bleed within the past 1 month, or conditions with estimated 6-month mortality of >50% were excluded from the study. The patients were randomized into low-dose methylprednisolone (MPT, n = 17, and no death) or placebo (n = 18 and two deaths) group. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics including age, weight, gender, race, pediatric risk of mortality (PRISM) III score, pediatric index of mortality-2 score, P/F ratio, PEEP, tidal volume (milliliter per kilogram), mean airway pressure, blood gas pH, PaCO2, and the number of lobes affected on chest X-ray. Only exceptions were higher plateau pressure of mechanical ventilation (p = 0.006) and lower pediatric logistic organ dysfunction scores (p = 0.04) in the MPT group. The causes of ARDS were mainly primary ARDS (>3/4 of the patients in both groups). The most common cause was pneumonia (12 in MPT and 7 in the placebo), followed by aspiration (5 in MPT and 7 in the placebo), bronchiolitis (4 in MPT and 3 in the placebo), and near drowning (2 in MPT and 2 in the placebo). The patients in the MPT group received a 2 mg/kg MPT loading dose within 72 h after diagnosis of ARDS, followed by a 1 mg/kg/day continuous infusion from days 1 to 7, then tapered off over 7 days. If patients were extubated before day 7, the dosage protocol was advanced to day 7 followed by tapering. Patients were ventilated according to ARDSnet recommendations modified for children using pressure regulated volume control mode of Servo-i ventilators (Maquet) set at tidal volume of 6–8 ml/kg (ideal body weight if the patient is obese). All the patients finished the study. Two patients died in the placebo group and no one in the MPT (p = 0.15). The duration of mechanical ventilation was 9.74 ± 6.62 days in the placebo group and 9.59 ± 5.21 days in the MPT (p = 0.94). There were no significant differences in ventilator-free days or length of stay in intensive care unit (ICU) or hospital between the groups. The MPT group had lower PaCO2 values on days 2 and 3, higher pH on day 2, higher PaO2/FiO2 ratios on days 8 and 9, fewer patients required racemic epinephrine inhalation treatment for post-extubation stridor, and fewer patients required supplemental oxygen at ICU transfer. MPT was not associated with any adverse effects, including secondary bacterial infection, hyperglycemia, and hypertension monitored regularly.

Plasma Samples

Blood samples were collected in lavender-top, EDTA-containing tubes at day 0 (before steroid administration) and day 7 during the randomized control trial. The blood samples were transported to our hospital central laboratory, centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and stored at −80°C until used.

Biomarker Analysis

We analyzed these plasma samples for MMP-8, Ang-2, PAI-1, sICAM-1, and sRAGE using a multiplex assay (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA, cat#HSP4MAG-63K, #HAGP1MAG-12K, #HSP1MAG-63K, #HSCRMAG-32K), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A standard curve was prepared over concentrations of 0.14–100 ng/ml for MMP-8, 13.7–10,000 pg/ml for Ang-2, 12–50,000 pg/ml for PAI-1 and sRAGE, and 60–250,000 pg/ml for sICAM-1. All samples were run in duplicates, and the average concentrations were used for statistical analysis. Only a few samples showed the biomarker values below or above the limit of the standard curve (two samples were above the limit on day 0 and one sample on day 7 below the limit for MMP-8. One sample on day 7 was below the limit for sRAGE).

Statistical Analysis

We used univariate (descriptive statistics and frequency distributions), bivariate (Fisher’s test for variability, t-tests, and Pearson’s correlations), and multivariate analyses (multivariate linear regressions using the least squares method) to evaluate the effects of MPT in pediatric ARDS. We used StatPlus (AnalystSoft, Inc.) for generating descriptive statistics and frequency distributions for all biomarker levels at days 0 and 7 for the placebo and MPT groups. We used Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc.) for comparing between the randomized groups at days 0 and 7, and comparing between days 0 and 7 within the MPT or placebo groups. Either the unpaired two-tailed t-test (parametric) or the Mann–Whitney U test (non-parametric) was used for group comparisons, after comparing their variances by the F test.

A correlation matrix for pairwise associations of Pearson correlation coefficients was also generated with simultaneously run t-tests for pathway analysis of the measured mediators. We used pairs of variables demonstrating strong correlation coefficients (R ≥ 0.7, p ≤ 0.01) to build multivariate regression models for predicting the clinical outcomes reported earlier (6), namely, PaO2/FiO2 (P/F) ratio on days 8 and 9, plateau pressure on days 1 and 2, PaCO2 on days 2 and 3, need for racemic epinephrine following extubation, or supplemental oxygen at ICU discharge.

We created bivariate correlation matrices and bar graphs using raw data without adjustment or imputation. Rarely, imputation of missing biomarker values was necessary to build the multivariate regression models explaining or contributing to glucocorticoid treatment-associated clinical outcomes. Biomarker values falling above or below the extreme values of the standard curve were assigned the highest or lowest values on the generated standard curve. Since these were exploratory, hypothesis-generating analyses, we did not make corrections for multiple comparisons between groups.

Results

Baseline and Time-Dependent Changes in Plasma Biomarker Levels

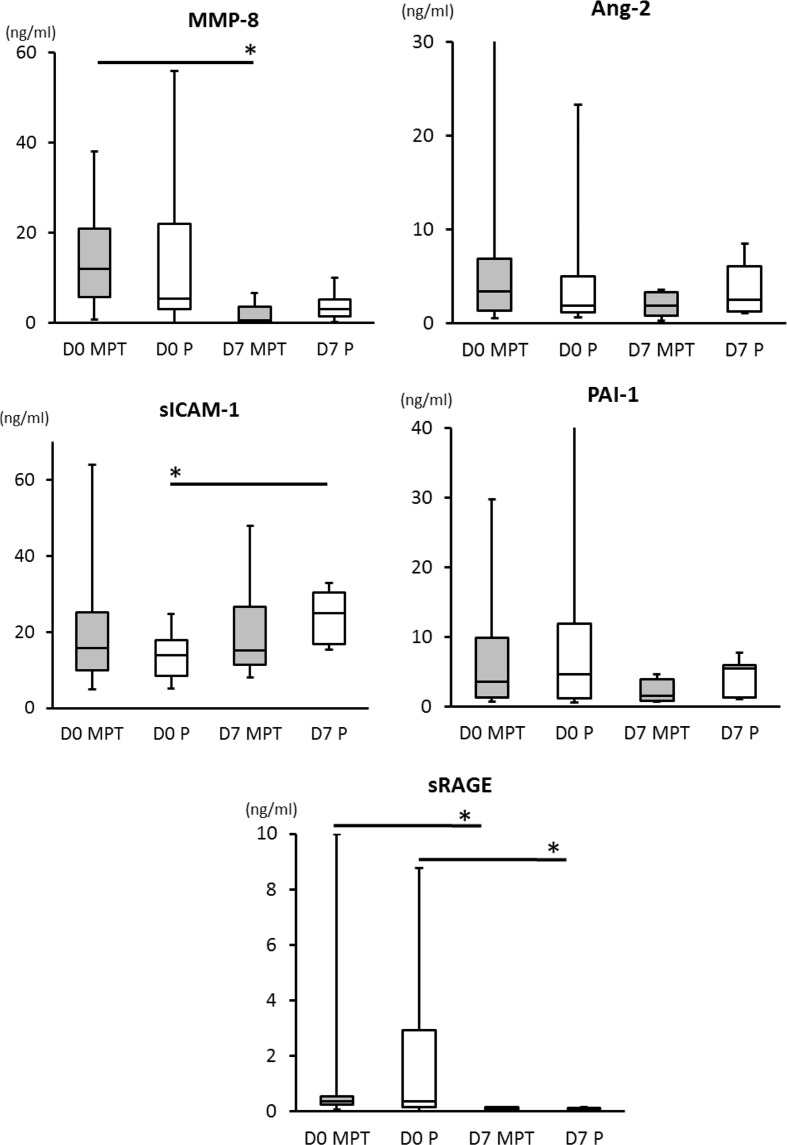

No differences occurred in the baseline concentrations of plasma biomarkers between the placebo and MPT groups on day 0 or on day 7. Within group, comparisons showed that MMP-8 levels decreased from day 0 to 7 (p = 0.0016) in the MPT group, but not in the placebo group. sICAM-1 levels increased significantly from day 0 to 7 (p = 0.0005) in the placebo group, but not in the MPT group. sRAGE levels decreased in both MPT and placebo groups (p < 0.0001) from day 0 to day 7 (Table 1). No significant differences occurred in Ang-2 and PAI-1 levels (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Significant results from comparison of biomarker levels within the placebo and the MPT groups between days 0 and 7.

| N | Median | 25% percentile | 75% percentile | Mean | SD | SEM | Two-tailed Mann–Whitney | Two-tailed unpaired t-test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPT, day 0: MMP-8 (ng/ml) | 15 | 12 | 6.4 | 23 | 20 | 25 | 6.3 | 0.0016 | |

| MPT, day 7: MMP-8 (ng/ml) | 6 | 0.63 | 0.28 | 4.8 | 2.1 | 2.7 | 1.1 | ||

| MPT, day 0: sRAGE (pg/ml) | 15 | 356 | 244 | 535 | 1,085 | 2,495 | 644 | 0.0007 | |

| MPT, day 7: sRAGE (pg/ml) | 6 | 74 | 16 | 136 | 79 | 62 | 25 | ||

| P, day 0: ICAM-1 (pg/ml) | 18 | 13,814 | 8,444 | 17,783 | 13,973 | 5,453 | 1,285 | 0.0005 | |

| P, day 7: ICAM-1 (pg/ml) | 7 | 24,824 | 16,710 | 30,346 | 24,461 | 6,859 | 2,592 | ||

| P, day 0: sRAGE (pg/ml) | 18 | 376 | 152 | 2,941 | 1,599 | 2,346 | 553 | 0.0018 | |

| P, day 7: sRAGE (pg/ml) | 7 | 77 | 29 | 131 | 79 | 49 | 19 | ||

| A-S, day 0: MMP-8 (ng/ml) | 32 | 10 | 3.9 | 23 | 19 | 25 | 4.4 | 0.0007 | |

| A-S, day 7: MMP-8 (ng/ml) | 13 | 1.9 | 0.47 | 5.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 0.86 | ||

| A-S, day 0: sRAGE (pg/ml) | 33 | 363 | 196 | 1,209 | 1,365 | 2,390 | 416 | <0.0001 | |

| A-S, day 7: sRAGE (pg/ml) | 13 | 77 | 26 | 127 | 79 | 53 | 15 |

Table of within-treatment group statistical differences, comparing days 0 to 7 levels of MMP-8, sRAGE, and ICAM-1. Day 0 compared to day 7 levels of PAI-1 and angiopoietin-2 did not differ. Methylprednisolone group (MPT), placebo group (P), all subjects (A-S), SD, and SEM.

Figure 1.

Comparisons of biomarker levels between placebo and the MPT groups on days 0 and 7. There are no differences between cytokine levels detected in MPT and control groups on day 0 or day 7. Two-tailed unpaired t or u test dependent were used dependent upon variances differences evaluated by F test. On day 7, we observed a significant reduction in plasma levels of MMP-8 (p = 0.0016) in the MPT and a significant increase in plasma levels of sICAM-1 (p = 0.0005) in the placebo group (MPT group had no increase by day 7). Levels of sRAGE decreased significantly in both the MPT and placebo groups (p < 0.002) from day 0 to day 7. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant (*).

Correlation between Biomarkers and Clinical Outcomes

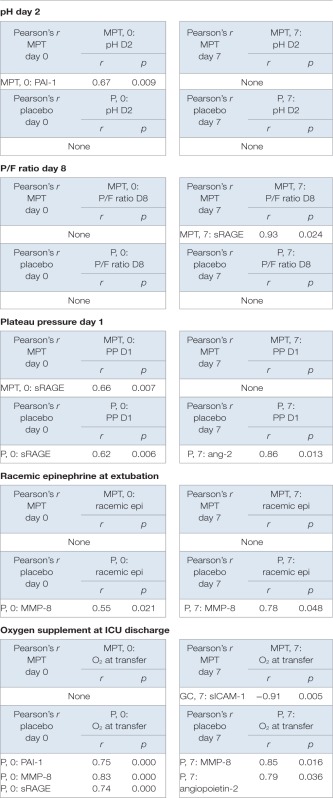

Pearson’s correlation tests analyzed associations between biomarker levels and the clinical outcomes reported previously (6), including (1) P/F ratios on days 8 and 9, (2) mechanical ventilator plateau pressures on days 1 and 2, (3) PaCO2 values on days 2 and 3, (4) pH values on day 2, (5) need for racemic epinephrine following extubation, and (6) supplemental oxygen at PICU discharge (Table 2).

Table 2.

Pearson’s correlation table showing pairwise comparisons of clinical parameters of diseases and other factors.

|

r is the Pearson’s correlation coefficient. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant and was derived from a paired, two-tailed t-test. MPT group (day 0: biomarkers n = 14–15 and clinical parameters n = 17 and day 7: biomarkers n = 7 and clinical parameters n = 8). Placebo group (day 0: biomarkers n = 16–18 and clinical parameters n = 18 and day 7: biomarkers n = 7 and clinical parameters n = 7).

Soluble receptor for activated glycation end product levels (r = 0.93, p = 0.024) on day 7 correlated positively with improved oxygenation (PaO2/FiO2 ratios) on day 8 in the MPT group (Table 2), but not in the placebo group. Plateau pressures on day 1 were positively correlated with sRAGE on day 0 in both MPT (r = 0.66, p = 0.007), and placebo (r = 0.62, p = 0.006) groups. Plateau pressure on day 1 was also positively correlated with Ang-2 on day 7 in the placebo group (r = 0.86, p = 0.013), but not in the MPT group.

PaCO2 levels on days 2 and 3 did not correlate with any biomarker levels in either group. High pH on day 2 correlated with PAI-1 in the MPT group (r = 0.67, p = 0.009), but not in the placebo group. Racemic epinephrine therapy at extubation was positively correlated with MMP-8 in the placebo group on both day 0 and day 8 (r = 0.55, p = 0.021 and r = 0.76, p = 0.048, respectively), but not in the MPT group.

Supplemental oxygen at ICU transfer was inversely correlated with sICAM-1 on day 7 in the MPT group (r = −0.91, p = 0.005), but in the placebo group, it positively correlated with PAI-1 on day 0 (r = 0.75, p = 0.000), MMP-8 on day 7 (r = 0.85, p = 0.016), and Ang-2 on day 7 (r = 0.79, p = 0.036).

Discussion

A randomized controlled trial of low-dose MPT for children with early pediatric ARDS (6) did not change mortality or morbidity (ventilator-free days at day 28) but altered the clinical parameters for oxygenation and ventilation. An observational study showed that 60% of pediatric patients received corticosteroids during the course of ARDS, and that exposure of corticosteroids for >24 h was independently associated with longer duration of mechanical ventilation (4). Those patients received corticosteroid with different regimens secondary to septic shock or other clinical indications. Thus, corticosteroid therapy for pediatric ARDS will remain controversial until larger controlled studies are performed. We propose that specific markers for endothelial or epithelial injury, coagulation and neutrophil activation, with known roles in the pathophysiology of ARDS, be selected as explanatory variables in future clinical trials.

In our study, MMP-8 levels decreased in the MPT group, but did not change in the placebo group. Also MMP-8 levels at days 0 and 7 positively correlated with supplemental O2 at transfer from PICU in the placebo group. The role of MMP-8 is not only extracellular matrix turnover but also positive modulation of inflammation and other physiological activities (9). In mice hyperoxia-induced acute lung injury model, MMP-8 was upregulated and seems to be produced in neutrophils, mesenchymal cell, and macrophages (10). In ventilator-induced lung injury model, absence of MMP-8 by knockout mice or specific inhibition of MMP-8 were associated with improved gas exchange, decreased lung edema and permeability, and decreased histological lung injury (11). Early elevations of MMP-8 in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid were associated with prolonged mechanical ventilation in pediatric ARDS (12), greater acute lung injury with higher PaO2/FiO2 ratios in adult patients (13), but did not predict their 90-day mortality (14). Overall decreases in MMP-8 levels seem to be associated with the reduction in local and systemic inflammation. In this study, MMP-8 levels did not decrease and were positively correlated with IL-6 and IL-10 on days 0 and 7 in the placebo group, possibly due to sustained active inflammation even on day 7 in the placebo group. Therefore, we can generate a hypothesis that MPT decreased lung inflammation via downregulation of MMP-8 in inflammatory cells, thus promoted early recovery from ARDS, and improved oxygenation in the recovery phase. This hypothesis needs to be validated in a future trial.

During sepsis or ARDS, Ang-2 is upregulated in the endothelium and believed to antagonize Ang-1. Upregulated Ang-2 is associated with impaired endothelial barrier function and increased adhesion and migration of inflammatory cells (15). Clinical studies in adults demonstrated higher plasma Ang-2 concentrations in ARDS patients (16), also associated with later development of ARDS (17), and ARDS mortality in adult patients (18, 19). Children with severe sepsis or septic shock have higher Ang-2 levels or Ang-2/Ang-1 ratios as compared to patients with SIRS (20). In this study, Ang-2 levels on day 7 correlated with plateau pressures on day 1 and the need for supplemental O2 at ICU discharge in the placebo group. This may indicate that acute lung injury on day 1 correlated with endothelial injury on day 7 and endothelial injury on day 7 correlated with oxygenation at ICU discharge. In the MPT group, Ang-2 levels on day 7 negatively correlated with IL-1RA. This may indicate that MPT may decrease endothelial injury via induction of anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-1RA.

Soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 is an adhesion molecule expressed in the membrane of leukocytes, vascular endothelium, and alveolar epithelium (21). It is involved in neutrophil recruitment into the lung. In adults, plasma sICAM-1 levels appear to correlate with ARDS development (22, 23) and ARDS mortality (22, 24, 25). In pediatric ARDS, early elevation of sICAM-1 was associated with prolonged duration of mechanical ventilation and increased mortality (26, 27). In this study, sICAM-1 levels increased from day 0 to 7 in the placebo group, whereas in the MPT group sICAM-1 levels on day 7 were positive predictors for O2 supplement at transfer. This indicates that MPT may prevent endothelial injury, decrease permeability, and improve pulmonary edema leading to improved oxygenation. sICAM-1 levels correlated with Ang-2 levels on days 0 and 7, indicating similar roles as endothelial injury biomarkers. Interestingly, both sICAM-1 and Ang-2 levels in the placebo group had positive correlation with many cytokines on day 7. However, in the MPT group, Ang-2 and sICAM-1 on day 7 did not correlate with these cytokines. These findings may indicate that the endothelial injury underlying pediatric ARDS may continue until later phases of ARDS, dependent upon the degree of the inflammation, if not treated with corticosteroid.

Soluble receptor for activated glycation end products, the secreted forms of the epithelial RAGE membrane receptors, are multiligand-binding receptors that can bind advanced glycation end products, amyloid beta-peptide, S100 proteins, and high-mobility group box-1. It results in activation of the pro-inflammatory transcription factor nuclear factor-kB (NF-kB) (28). sRAGE levels in plasma and BAL were elevated in rat models of lung injury (29). In adult ARDS studies, its results are controversial. In adult ARDS, sRAGE level was associated with ARDS development and mortality (30, 31). However, in other studies, sRAGE did not show any association with the development of ARDS (17, 32, 33). Recent study demonstrated that serum sRAGE was elevated in children with severe bronchiolitis (34); however, there are no published data in pediatric ARDS. In this study, sRAGE levels decreased in all subjects, MPT, and the placebo groups from days 0 to 7. Furthermore, sRAGE levels on day 0 are predictors of higher plateau pressure on day 1 in both the groups. This indicates that higher plateau pressure correlated with more epithelial injury in early ARDS. However, by day 7, sRAGE levels decreased in both the MPT and placebo groups. Does this indicate that epithelial injury is more likely in the early stages of ARDS compared to the later stage? sRAGE levels on day 0 positively correlated with IL-6 levels in both the MPT and placebo groups, and this could be a manifestation of the pro-inflammatory effect of sRAGE.

Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 is an anti-fibrinolytic agent. During ARDS, deposition of fibrin in the alveolar space is observed with disruption of the lung endothelial and alveolar epithelial barrier (35). Elevation of PAI-1 activity in plasma and air spaces associated with a decrease in alveolar fibrinolysis is observed in early ARDS (36). In a secondary analysis from adult ARDS patients, an elevated plasma PAI-1 level was significantly associated with poor oxygenation (37). Elevated plasma PAI-1 was also associated with mortality in pediatric ARDS (38). In this study, PAI-1 levels on day 0 correlated positively with high pH in the MPT group and were predictors of high pH on day 2 in our linear regression model. On day 0, PAI-1 level correlated positively with many cytokines and chemokines. This indicates that increased severity of inflammation may be associated with the deposition of fibrin in earlier stages of ARDS.

In adult ARDS, the same MPT protocol was associated with decreases in plasma IL-6 and proadrenomedullin levels and increases in protein C levels, compared to the placebo (39). As previously reported, MPT decreased IL-6 in pediatric ARDS as well (8). Considering the biomarker changes in this study, we propose that corticosteroids may attenuate inflammation, promote early recovery from the epithelial injury, and prevent sustained endothelial damage, leading to earlier improvement in pulmonary edema and oxygenation seen as clinical outcomes. This hypothesis should be tested in larger clinical trials of MPT in pediatric ARDS in the future.

This is the first study to measure plasma biomarkers for endothelial and epithelial injury at the different time points of pediatric ARDS. However, proteomic analysis methods have further advanced, and now it is technically possible to measure 1,310 protein levels simultaneously and precisely from just 150 μl of plasma samples (40, 41). Combinations of these biomarkers could discover novel therapeutic options and predictors of clinical outcomes in the future.

Limitations of this study include a relatively small number of samples; therefore, our results need to be validated in larger clinical trials. Our clinical trial was designed to demonstrate the feasibility of the MPT protocol in pediatric early ARDS. Our biomarker analysis was not the main purpose of the study and we could not conduct functional analyses. Also, we only obtained clinical samples on days 0 and 7, whereas the timing for peak levels of these biomarkers may be different. Finally, we did not conduct BAL fluid collection or lung biopsy, so our results may not represent local pulmonary the changes but may represent systemic changes.

Conclusion

In this study, we demonstrated changes in selected biomarkers of ARDS between the placebo and MPT groups that were correlated with clinical endpoints. We cannot provide meaningful conclusions due to small sample size. However, we can generate a hypothesis that the anti-inflammatory effects of MPT may allow faster epithelial recovery manifested by decreases in sRAGE levels, thus avoiding sustained endothelial injury associated with elevated sICAM-1 levels in the placebo group. Future controlled studies with larger sample sizes should validate this hypothesis.

Author Contributions

DK, SC, and KA: conception and design of study. DK: acquisition of data. DK, JS, CR, GM, AS, SC, and KA: analysis and interpretation of data and drafting and critically revising the manuscript. All the authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding

This study was supported by National Institute of Health (7KO8HL118118-03, R01AI090059, R01ES015050, P42ES013648) and Le Bonheur Foundation grant (641003). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

Ang-2, angiopoietin-2; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; ICU, intensive care unit; MMP-8, matrix metalloproteinase-8; MPT, methylprednisolone; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; PICU, pediatric intensive care unit; sICAM-1, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1; SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome; sRAGE, soluble receptor for activated glycation end products.

References

- 1.Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med (2000) 342(18):1334–49. 10.1056/NEJM200005043421806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hough CL. Steroids for acute respiratory distress syndrome? Clin Chest Med (2014) 35(4):781–95. 10.1016/j.ccm.2014.08.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meduri GU, Golden E, Freire AX, Taylor E, Zaman M, Carson SJ, et al. Methylprednisolone infusion in early severe ARDS: results of a randomized controlled trial. Chest (2007) 131(4):954–63. 10.1378/chest.06-2100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yehya N, Servaes S, Thomas NJ, Nadkarni VM, Srinivasan V. Corticosteroid exposure in pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med (2015) 41(9):1658–66. 10.1007/s00134-015-3953-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwingshackl A, Meduri GU, Kimura D, Cormier SA, Anand KJ. Corticosteroids in pediatric ARDS: all cards on the table. Intensive Care Med (2015) 41(11):2036–7. 10.1007/s00134-015-4027-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drago BB, Kimura D, Rovnaghi CR, Schwingshackl A, Rayburn M, Meduri GU, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot randomized trial of methylprednisolone infusion in pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome. Pediatr Crit Care Med (2015) 16(3):e74–81. 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meduri GU, Marik PE, Chrousos GP, Pastores SM, Arlt W, Beishuizen A, et al. Steroid treatment in ARDS: a critical appraisal of the ARDS network trial and the recent literature. Intensive Care Med (2008) 34(1):61–9. 10.1007/s00134-007-0933-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwingshackl A, Kimura D, Rovnaghi CR, Saravia SJ, Cormier AS, Teng B, et al. Regulation of inflammatory biomarkers by intravenous methylprednisolone in pediatric ARDS patients: results from a double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized pilot trial. Cytokine (2016) 77(1):63–71. 10.1016/j.cyto.2015.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dejonckheere E, Vandenbroucke RE, Libert C. Matrix metalloproteinase8 has a central role in inflammatory disorders and cancer progression. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev (2011) 22(2):73–81. 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2011.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cederqvist K, Janer J, Tervahartiala T, Sorsa T, Haglund C, Salmenkivi K, et al. Up-regulation of trypsin and mesenchymal MMP-8 during development of hyperoxic lung injury in the rat. Pediatr Res (2006) 60(4):395–400. 10.1203/01.pdr.0000238342.16081.f9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albaiceta GM, Gutierrez-Fernandez A, Garcia-Prieto E, Puente XS, Parra D, Astudillo A, et al. Absence or inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase-8 decreases ventilator-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol (2010) 43(5):555–63. 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0034OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kong MY, Gaggar A, Li Y, Winkler M, Blalock JE, Clancy JP. Matrix metalloproteinase activity in pediatric acute lung injury. Int J Med Sci (2009) 6(1):9–17. 10.7150/ijms.6.9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fligiel SE, Standiford T, Fligiel HM, Tashkin D, Strieter RM, Warner RL, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases and matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors in acute lung injury. Hum Pathol (2006) 37(4):422–30. 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hastbacka J, Linko R, Tervahartiala T, Varpula T, Hovilehto S, Parviainen I, et al. Serum MMP-8 and TIMP-1 in critically ill patients with acute respiratory failure: TIMP-1 is associated with increased 90-day mortality. Anesth Analg (2014) 118(4):790–8. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parikh SM. Dysregulation of the angiopoietin-Tie-2 axis in sepsis and ARDS. Virulence (2013) 4(6):517–24. 10.4161/viru.24906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van der Heijden M, van Nieuw Amerongen GP, Koolwijk P, van Hinsbergh VW, Groeneveld AB. Angiopoietin-2, permeability oedema, occurrence and severity of ALI/ARDS in septic and non-septic critically ill patients. Thorax (2008) 63(10):903–9. 10.1136/thx.2007.087387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agrawal A, Matthay MA, Kangelaris KN, Stein J, Chu JC, Imp BM, et al. Plasma angiopoietin-2 predicts the onset of acute lung injury in critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2013) 187(7):736–42. 10.1164/rccm.201208-1460OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gallagher DC, Parikh SM, Balonov K, Miller A, Gautam S, Talmor D, et al. Circulating angiopoietin 2 correlates with mortality in a surgical population with acute lung injury/adult respiratory distress syndrome. Shock (2008) 29(6):656–61. 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31815dd92f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calfee CS, Gallagher D, Abbott J, Thompson BT, Matthay MA, Network NA. Plasma angiopoietin-2 in clinical acute lung injury: prognostic and pathogenetic significance. Crit Care Med (2012) 40(6):1731–7. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182451c87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giuliano JS, Jr, Lahni PM, Harmon K, Wong HR, Doughty LA, Carcillo JA, et al. Admission angiopoietin levels in children with septic shock. Shock (2007) 28(6):650–4. 10.1097/shk.0b013e318123867b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van de Stolpe A, van der Saag PT. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1. J Mol Med (1996) 74(1):13–33. 10.1007/BF00202069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calfee CS, Eisner MD, Parsons PE, Thompson BT, Conner ER, Jr, Matthay MA, et al. Soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and clinical outcomes in patients with acute lung injury. Intensive Care Med (2009) 35(2):248–57. 10.1007/s00134-008-1235-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cepkova M, Brady S, Sapru A, Matthay MA, Church G. Biological markers of lung injury before and after the institution of positive pressure ventilation in patients with acute lung injury. Crit Care (2006) 10(5):R126. 10.1186/cc4842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McClintock D, Zhuo H, Wickersham N, Matthay MA, Ware LB. Biomarkers of inflammation, coagulation and fibrinolysis predict mortality in acute lung injury. Crit Care (2008) 12(2):R41. 10.1186/cc6846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calfee CS, Ware LB, Glidden DV, Eisner MD, Parsons PE, Thompson BT, et al. Use of risk reclassification with multiple biomarkers improves mortality prediction in acute lung injury. Crit Care Med (2011) 39(4):711–7. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318207ec3c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flori HR, Ware LB, Glidden D, Matthay MA. Early elevation of plasma soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in pediatric acute lung injury identifies patients at increased risk of death and prolonged mechanical ventilation. Pediatr Crit Care Med (2003) 4(3):315–21. 10.1097/01.PCC.0000074583.27727.8E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samransamruajkit R, Prapphal N, Deelodegenavong J, Poovorawan Y. Plasma soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (sICAM-1) in pediatric ARDS during high frequency oscillatory ventilation: a predictor of mortality. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol (2005) 23(4):181–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmidt AM, Yan SD, Yan SF, Stern DM. The multiligand receptor RAGE as a progression factor amplifying immune and inflammatory responses. J Clin Invest (2001) 108(7):949–55. 10.1172/JCI200114002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uchida T, Shirasawa M, Ware LB, Kojima K, Hata Y, Makita K, et al. Receptor for advanced glycation end-products is a marker of type I cell injury in acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2006) 173(9):1008–15. 10.1164/rccm.200509-1477OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakamura T, Sato E, Fujiwara N, Kawagoe Y, Maeda S, Yamagishi S. Increased levels of soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products (sRAGE) and high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) are associated with death in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Clin Biochem (2011) 44(8–9):601–4. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Narvaez-Rivera RM, Rendon A, Salinas-Carmona MC, Rosas-Taraco AG. Soluble RAGE as a severity marker in community acquired pneumonia associated sepsis. BMC Infect Dis (2012) 12:15. 10.1186/1471-2334-12-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Determann RM, Millo JL, Waddy S, Lutter R, Garrard CS, Schultz MJ. Plasma CC16 levels are associated with development of ALI/ARDS in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia: a retrospective observational study. BMC Pulm Med (2009) 9:49. 10.1186/1471-2466-9-49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Determann RM, Royakkers AA, Haitsma JJ, Zhang H, Slutsky AS, Ranieri VM, et al. Plasma levels of surfactant protein D and KL-6 for evaluation of lung injury in critically ill mechanically ventilated patients. BMC Pulm Med (2010) 10:6. 10.1186/1471-2466-10-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garcia-Salido A, Onoro G, Melen GJ, Gomez-Pina V, Serrano-Gonzalez A, Ramirez-Orellana M, et al. Serum sRAGE as a potential biomarker for pediatric bronchiolitis: a pilot study. Lung (2015) 193(1):19–23. 10.1007/s00408-014-9663-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ware LB, Matthay MA, Parsons PE, Thompson BT, Januzzi JL, Eisner MD, et al. Pathogenetic and prognostic significance of altered coagulation and fibrinolysis in acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med (2007) 35(8):1821–8. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000221922.08878.49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bertozzi P, Astedt B, Zenzius L, Lynch K, LeMaire F, Zapol W, et al. Depressed bronchoalveolar urokinase activity in patients with adult respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med (1990) 322(13):890–7. 10.1056/NEJM199003293221304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Agrawal A, Zhuo H, Brady S, Levitt J, Steingrub J, Siegel MD, et al. Pathogenetic and predictive value of biomarkers in patients with ALI and lower severity of illness: results from two clinical trials. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol (2012) 303(8):L634–9. 10.1152/ajplung.00195.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sapru A, Curley MA, Brady S, Matthay MA, Flori H. Elevated PAI-1 is associated with poor clinical outcomes in pediatric patients with acute lung injury. Intensive Care Med (2010) 36(1):157–63. 10.1007/s00134-009-1690-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seam N, Meduri GU, Wang H, Nylen ES, Sun J, Schultz MJ, et al. Effects of methylprednisolone infusion on markers of inflammation, coagulation, and angiogenesis in early acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med (2012) 40(2):495–501. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232da5e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen X, Shan Q, Jiang L, Zhu B, Xi X. Quantitative proteomic analysis by iTRAQ for identification of candidate biomarkers in plasma from acute respiratory distress syndrome patients. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2013) 441(1):1–6. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.09.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gold L, Walker JJ, Wilcox SK, Williams S. Advances in human proteomics at high scale with the SOMAscan proteomics platform. N Biotechnol (2012) 29(5):543–9. 10.1016/j.nbt.2011.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]