Abstract

Sarcolemmal ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels control skeletal muscle energy use through their ability to adjust membrane excitability and related cell functions in accordance with cellular metabolic status. Mice with disrupted skeletal muscle KATP channels exhibit reduced adipocyte size and increased fatty acid release into the circulation. As yet, the molecular mechanisms underlying this link between skeletal muscle KATP channel function and adipose mobilization have not been established. Here, we demonstrate that skeletal muscle-specific disruption of KATP channel function in transgenic (TG) mice promotes production and secretion of musclin. Musclin is a myokine with high homology to atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) that enhances ANP signaling by competing for elimination. Augmented musclin production in TG mice is driven by a molecular cascade resulting in enhanced acetylation and nuclear exclusion of the transcription factor forkhead box O1 (FOXO1) – an inhibitor of transcription of the musclin encoding gene. Musclin production/secretion in TG is paired with increased mobilization of fatty acids and a clear trend toward increased circulating ANP, an activator of lipolysis. These data establish KATP channel-dependent musclin production as a potential mechanistic link coupling “local” skeletal muscle energy consumption with mobilization of bodily resources from fat. Understanding such mechanisms is an important step toward designing interventions to manage metabolic disorders including those related to excess body fat and associated co-morbidities.

Keywords: action potential, calcium, natriuretic peptide, fatty acid, endurance

Introduction

Skeletal muscles account for about 40–50% of body mass and are major consumers of bodily energy. Recently we established that skeletal muscle energy efficiency is regulated by ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels [1,2,3]. KATP channels control energy use through their ability to adjust membrane excitability and related cell functions in accordance with the metabolic status of the cell [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. Specifically, sarcolemmal KATP channel opening limits skeletal muscle energy consumption, not only in response to high metabolic stress [5,6,7,8,9,10], but also in response to metabolic changes associated with moderate activity [1,2,3]. This function balances energy use and availability by preventing excessive muscle utilization of cellular energy resources, thereby enhancing energy efficiency and endurance [1,2,3]. Conversely, disruption of KATP channel function forces an increased cost of skeletal muscle performance, resulting in greater heat production, lower endurance and a lean phenotype [1,2,3]. Furthermore, mice with disrupted KATP channel function exhibit reduced adipocyte size and increased release of fatty acids into the circulation [2,3]. As yet, the molecular mechanisms underlying this link between skeletal muscle KATP channel function and adipose tissue mobilization have not been established.

Traditionally physical activity-related lipolysis has been linked to sympathetic activation [11,12]. However, recently, adipose tissue metabolic regulation was also attributed to the action of atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), a hormone secreted predominantly by atrial myocytes at increased rates in response to hemodynamic and metabolic stress including exercise [13,14,15]. The biologic activity of ANP is mainly through natriuretic peptide receptor A (NPRA) which has an intracellular guanylyl cyclase catalytic domain [13]. Binding of ANP to NPRA activates guanylyl cyclase leading to increased intracellular cGMP [13]. ANP-dependent cGMP elevations linked to lipolysis were demonstrated both in isolated fat cells and in vivo [13,15,16,17,18,19]. Elimination of ANP from the plasma occurs mainly through binding the natriuretic peptide clearance receptor, NPRC, resulting in internalization and degradation of ANP [14]. It was recently demonstrated that ANP levels are affected by competition between ANP and the structurally related signaling peptide secreted by skeletal muscle, musclin (AKA osteocrin), for binding to NPRC [20,21,22,23]. Musclin binds to NPRC with affinity comparable to NPs, but exhibits only weak binding to NPRA and NPRB and no activation of the linked guanylyl cyclase that is the primary effector of traditional NP physiologic actions [20]. Importantly, upregulation of ANP synthesis and secretion by atrial cardiomyocytes has been linked to cardiac KATP channel dysfunction [24,25]. Whether there is a similar connection between skeletal muscle KATP channels and musclin production is unknown.

Here we establish that disruption of KATP channel function promotes production and secretion of musclin by skeletal muscles. This occurs in the setting of a molecular cascade that results in acetylation and nuclear exclusion of the transcriptional factor forkhead box O1 (FOXO1), known to inhibit musclin gene transcription [23,26]. Increased skeletal muscle musclin production and secretion in the presence of KATP channel deficit is associated with increased plasma ANP and fatty acid levels following physical activity. These data establish KATP channel-dependent musclin production and its effects on ANP signaling as a potential mechanistic link between skeletal muscle energy consumption and mobilization of fuel resources from fat. Understanding such molecular mechanisms is an important step toward designing interventions to manage metabolic disorders including those related to excess body fat and associated co-morbidities.

Materials and Methods

Mouse models

All animal protocols conform to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals generated by the Institute for Laboratory Animal Research, National Research Council of the National Academies, and are approved by the University of Iowa Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Mice of either gender, aged 10–12 weeks, are used. The transgenic Tg[MyoD-Kir6.1AAA] model (TG) exhibits skeletal muscle-specific expression of the dominant-negative mutant pore-forming KATP channel subunit Kir6.1AAA [3]. TG mice are compared to green fluorescence protein-expressing controls (GFP) and wildtype (WT) mice of the same age and background [3]. Mice are fasted for 6 hours prior to exercise testing and blood/tissue collection.

For invasive procedures mice are anesthetized with isoflurane (5% induction, ~1.0–1.5% maintenance, Piramal Healthcare, Andhra Pradesh, India) via a nose-cone to maintain a respiratory rate ~50–60 breaths per minute.

Exercise

A multi-lane treadmill (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH) is used to simultaneously exercise model mice and controls. Mice are acclimated on the treadmill 20 min/day for 3 days at 3.5 m/min and 15° inclination. Mice are then exercised once at 10 m/min and inclination of 15° for 45 min immediately before sample (blood, tissue) collection.

Molecular Biology

RNA isolation, quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), nuclear and whole cell protein extraction and western blot are performed as previously described [23]. Antibodies to HDAC4 are obtained from Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA.

Histology of skeletal muscles is as previously described [23].

Musclin and non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA) are measured as described [3,23]. ANP was measured by ELISA using a commercially available kit according to manufacturer instructions (RayBiotech, Norcross, GA).

Statistics

Results are expressed as mean±SEM

Comparisons between two groups are made using the 2-sided Student’s t-test and between more than two groups using analysis of variance (ANOVA). A p value <.05 is considered significant. Sigma Plot 11 is used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Disruption of KATP channel function in skeletal muscles promotes musclin production

Stretch-dependent production of ANP by atria in the heart has been demonstrated to be inhibited by the activity of sarcolemmal KATP channels [24,25]. Here, we test whether skeletal muscle production of musclin is also under control of KATP channels. Mice with skeletal muscle-specific expression of a dominant-negative KATP channel pore-forming subunit (TG), which are previously confirmed to have absence of skeletal muscle sarcolemmal KATP channel activity [2,3], were compared to GFP-expressing littermates (GFP) and age matched wildtype (WT) controls, both of which have normal skeletal muscle KATP channel activity [2,3]. Previous characterization of the TG model indicates no changes in fiber type composition but a loss of skeletal muscle membrane/action potential adaptation to exercise with increased calcium release compared to controls [2]. These differences result in excess muscle caloric consumption from contraction and ion re-sequestration and a leaner phenotype compared to controls [2,3]. Here, we find that expression of musclin is significantly increased in limb muscles of TG mice, compared to GFP and WT, when assayed by western blot (1.44±.14, 1.48±.09, 2.05±.18 AU, n=5, 5, and 4 for TG, GFP and WT respectively, p<.05 for TG vs. GFP or WT, Fig. 1A, C), immunohistochemistry (28.5±1.73, 26.40±1.51, 53.45±2.46 AU, n=14 each for TG, GFP and WT respectively, p<.05 for TG vs. GFP or WT, Fig. 1B), or PCR for mRNA (1±.09, .89±.17, 2.63±.55 AU, n=6, 3, and 6 for TG, GFP and WT respectively, p<.05 for TG vs. GFP or WT Fig. 1E).

Figure 1. Expression of musclin is increased in KATP channel deficient skeletal muscle.

A) Representative western blots of musclin vs. GAPDH obtained from whole cell protein extracts of gastrocnemius muscle from WT, GFP and TG mice. B) Representative cross-sections of gastrocnemius muscle from WT, GFP and TG mice with labeling by immunofluorescent antibodies against musclin (red) and DAPI (blue). Summary statistics for musclin expression of WT, GFP and TG as probed by C) western blot of musclin protein normalized to GAPDH in whole cell protein extracts of gastrocnemius muscle, D) quantification of fluorescence by immunocytochemistry of musclin protein in muscle cross sections of gastrocnemius muscle and E) PCR of musclin mRNA from tibialis anterior normalized to WT level (*p<.05). DAPI: 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

Disruption of KATP channel function relieves FOXO1 inhibition of musclin transcription

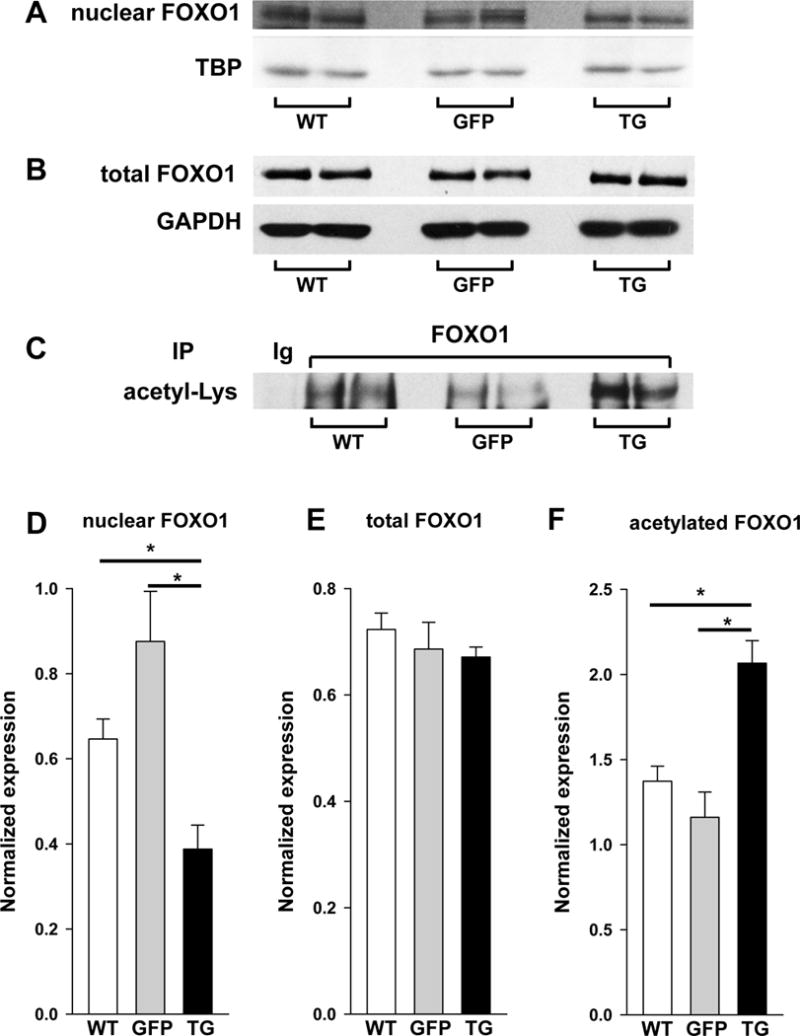

Regulation of musclin transcription has been linked to FOXO1 activity [21,23,27]. As demonstrated in cell culture and in vivo, nuclear export of FOXO1 releases transcription of the musclin gene from inhibition [23,26]. Here, we demonstrate that that disruption of KATP channel function is coupled to reduced FOXO1 in nuclei of skeletal muscles (Fig. 2A, D; .65±.05, .88±.12, .39±.06 AU, n= 5, 4, and 5 for WT, GFP and TG respectively, p<.05 for TG vs. WT or GFP). FOXO1 export from nuclei occurs with phosphorylation by AKT or through acetylation [26]. In KATP channel deficient skeletal muscles of TG mice, total FOXO1 is not different from controls (Fig. 2B, E; .72±.03, .69±.05, .67±.02 AU, for WT, GFP and TG respectively, n=4 each, p=NS for all comparisons), however acetylated FOXO1 is significantly increased (Fig. 2C, F; 1.37±.09, 1.16±.149, 2.07±.13 AU, n=12, 8 and 8 for WT, GFP and TG respectively, p<.05 for TG vs. WT or GFP). This shift to greater acetylation and nuclear export of FOXO1 in skeletal muscles of TG mice is paralleled by decreased nuclear content of histone deacetylase 4 (HDAC4, Fig. 3A, D; 1.35±.12, 1.61±.16, .87±.08 for WT, GFP and TG respectively, n=4 each, p<.05 for TG vs. WT or GFP) shown to diminish HDAC3-mediated deacetylation and activation of FOXO1 [28]. The nuclear export of FOXO1 in TG is also paralleled by an elevated presence of CaMKII activated by phosphorylation (p-CaMKII), a negative regulator of HDAC4 nuclear localization [29]. Specifically, phosphorylated CaMKII (p-CaMKII), but not total CaMKII (t-CaMKII) is significantly increased in nuclear extracts of limb muscle from TG compared to controls (p-CaMKII; Fig. 3B, E; 1.41±.04, 1.61±.12, 2.36±.24 for WT, GFP and TG respectively, n=4 each, p<.05 for TG vs. WT or GFP, t-CaMKII; Fig. 3C, F; 3.41±.08, 3.51±.20, 3.65±.06 for WT, GFP and TG respectively, n=4 each, p=NS for all comparisons). These findings are consistent with prior studies indicating that KATP channel-deficient cardiac and skeletal myocytes, including those generated using the Kir6.1AAA transgene expressed in this study, have increased contractile calcium release and calcium loading [1,2,3,4,5,6,30,31,32].

Figure 2. Acetylation and nuclear exclusion of FOXO1 are increased in KATP channel deficient skeletal muscle.

A) Representative western blots of FOXO1 vs. TBP in nuclear isolates from gastrocnemius muscle of WT, GFP and TG mice. B) Representative western blot of total FOXO1 vs. GAPDH and C) representative immunoprecipitation (IP) of FOXO1 with blot against acetylated lysine (Acetyl-Lys) in whole cell extracts of gastrocnemius muscle from WT, GFP and TG mice. Summary statistics of D) optical density of FOXO1 normalized to TBP in nuclear extracts from gastrocnemius muscle of WT, GFP and TG mice, E) optical density of total FOXO1 normalized to GAPDH from western blots in whole cell protein extracts and F) immunoprecipitation of FOXO1 with blot against Acetyl-Lys in nuclear extracts (*p<.05).

Figure 3. Phosphorylated CaMKII is increased and HDAC4 decreased in nuclei of KATP channel deficient skeletal muscles.

Representative western blots of A) HDAC4, B) phosphorylated CaMKII (p-CaMKII) and C) total CaMKII (t-CaMKII) vs. TBP in nuclei of gastrocnemius muscles from WT, GFP and TG mice. Summary statistics for optical density of D) HDAC4, E) p-CaMKII and F) t-CaMKII normalized to optical density of TBP on western blots from nuclear extracts of gastrocnemius muscle of WT, GFP and TG mice (*p<.05).

Increased musclin production by KATP channel-deficient skeletal muscles is associated with greater mobilization of fatty acids

Mice with KATP channel-deficient skeletal muscles have increased energy expenditure [2,3] and therefore require greater energy resources to maintain muscle function. Musclin has been previously shown to regulate plasma ANP – a potent stimulator of lipolysis, particularly related to physical activity [15,16,18,19,20,23]. Here, after a single episode of low-intensity exercise, TG mice compared to controls display higher circulating levels of musclin (12.83±1.42 n=9, 6.96±1.06 n=7, 6.60±2.08 pg/ml n=4, for TG, WT and GFP, respectively, p<.05 for TG vs. WT or GFP; Fig. 4A) and a clear trend toward elevated circulating ANP (60.70±9.25 n=5, 36.36±6.83 n=5, 40.57±4.69 pg/ml n=6 for TG, WT and GFP, respectively, p=.07 for TG vs. GFP and p=.07 for TG vs. WT; Fig. 4B). When circulating ANP levels in TG mice are compared with combined controls, the difference is statistically significant (60.70±9.25 n=5 vs. 38.66±3.86 n=11, p=.02). These increases in musclin and ANP are associated with greater serum levels of non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA). Specifically, NEFA is greater in TG (.82±.07 mmol/ml, n=6) compared with WT (.51±.05, n=6, p<.05 vs. TG) and GFP controls (.57±.04 mmol/ml, n=4, p<.05 vs. TG; Fig. 4C).

Figure 4. Mice with absence of functional skeletal muscle sarcolemmal KATP channels exhibit increased serum NEFA following exercise.

Summary statistics for A) plasma musclin, B) plasma ANP and C) serum NEFA measured after exercise in WT, GFP, and TG mice (*p<.05).

Discussion

KATP channels are membrane protein complexes vital for preservation of cellular energy balance under normal and disease conditions [1,2,3,5,8,10,24,25,30,31,32]. Here we use tissue-specific transgenic expression of a dominant-negative KATP channel subunit to selectively eliminate skeletal muscle KATP channel current. This intervention is associated with a blunted myofiber membrane/action potential adaptation to muscle contractions that results in increased intracellular calcium release [2]. We previously demonstrated that a calcium-dependent mechanism, protein kinase B (AKT) phosphorylation of FOXO1, underlies skeletal muscle exercise-dependent production of musclin [23]. In the current study, there are no significant differences in AKT phosphorylation between control and TG mice (data not shown). This could be due an actual absence of a role for AKT in increased musclin production by TG mice, or to the short-lived nature of AKT phosphorylation such that the window for detecting significant differences is missed when collecting tissue at a single time point. However, another calcium-dependent mechanism for production of musclin is evidenced by CaMKII activation that can increase FOXO1 nuclear export by promoting its acetylation. This signaling cascade represents a previously unrecognized pathway for regulation of musclin transcription. We expect that the calcium homeostatic regulatory property of skeletal muscle KATP channels is an important link between muscle energetics and musclin production. Other mechanisms that regulate cellular calcium, including mitochondrial function, could also have significant effects.

Our previous work indicates that musclin production is associated with improved physical performance and enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis [23]. However, the TG model used here, despite its increased musclin production, has been characterized by decreased muscle energy efficiency and reduced exercise tolerance [2,3]. We interpret this to indicate that higher musclin production and secretion in TG functions to partially compensate for loss of KATP channel dependent control of myofiber energetics. For instance greater musclin production, with consequent mitochondrial biogenesis and adipose mobilization, may serve to generate the increased energy needed to support the function of calorically wasteful muscle [2,3].

The TG mouse model has also been previously demonstrated to manifest with lower body weight, reduced adipocyte size, and greater lipolysis [2,3]. Given the pattern of musclin, ANP and serum NEFA in TG compared with controls, the current study supports the hypothesis that musclin enhances ANP-driven lipolysis as a mechanism for fatty acid mobilization. Specifically, we hypothesize that increased musclin and ANP in the TG are related, due to reduced clearance of ANP as a result of musclin competing for binding to the NP clearance receptor [20,33]. Binding of ANP to NPRA activates guanylyl cyclase leading to increased intracellular cGMP [13]. ANP-dependent cGMP elevations and lipolysis were demonstrated both in isolated fat cells and in vivo [15,16,18,19,34]. However, it is also possible that a musclin-induced rise in ANP stimulates lipolysis through a cGMP independent pathway. For instance, in vivo the vasodilatory and natriuretic properties of ANP favor sympathetic activation that could then result in fat mobilization [11,12,13]. Furthermore, it has been postulated that NPRC could have its own signaling function [35] such that musclin binding to NPRC may have a more direct effect on lipolysis than by boosting ANP levels. Further dissection of downstream lipolytic mechanisms promoted by musclin will be the aim of future studies.

In summary, data presented here introduce a mechanistic link between skeletal muscle energy consumption, lean phenotype, and adipose mobilization in a mouse model of skeletal muscle KATP channel deficit. More importantly, these data suggest a role for normal function of skeletal muscle sarcolemmal KATP channels not only in regulation of muscle energy consumption, as shown previously, but also as important regulators of a biochemical cascade responsible for delivery of nutrients to muscles through adipose mobilization. Examination of these mechanisms could uncover novel therapeutic targets for diseases of muscle and fat metabolism.

Highlights.

ATP-sensitive K+ channels regulate musclin production by skeletal muscles

Lipolytic ANP signaling is promoted by augmented skeletal muscle musclin production

Skeletal muscle musclin transcription is promoted by a CaMKII/HDAC/FOXO1 pathway

Musclin links adipose mobilization to energy use in KATP channel deficient skeletal muscle

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [HL113089 to D.M.H-Z., DK092412 to L.Z., HL085820 and HL126905 to W.A.C., AR052777 to D.J.G.]; The VA Merit Review Program [1I0BX000718 to L.Z.].

Abbreviations

- AKT

protein kinase B

- ANP

atrial natriuretic peptide

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- CaMKII

calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II

- FOXO1

forkhead box O1 transcription factor

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GFP

green fluorescence protein

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- KATP

ATP-sensitive potassium

- IKATP

KATP channel current

- NEFA

non-esterified fatty acids

- NPR

natriuretic peptide receptor

- TBP

TATA-binding protein

- TG

transgenic

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Ana Sierra, Email: ana-sierra@uiowa.edu.

Ekaterina Subbotina, Email: ekaterina-subbotina@uiowa.edu.

Zhiyong Zhu, Email: zhiyong-zhu@uiowa.edu.

Zhan Gao, Email: zhan-gao@uiowa.edu.

Siva Rama Krishna Koganti, Email: sivaramakrishna.koganti@ttuhc.edu.

William Coetzee, Email: william.coetzee@nyumc.org.

David Goldhamer, Email: david.goldhamer@uconn.edu.

Denice M. Hodgson-Zingman, Email: denice-zingman@uiowa.edu.

Leonid V. Zingman, Email: leonid-zingman@uiowa.edu.

References

- 1.Koganti SR, Zhu Z, Subbotina E, Gao Z, Sierra A, Proenza M, Yang L, Alekseev A, Hodgson-Zingman D, Zingman L. Disruption of KATP channel expression in skeletal muscle by targeted oligonucleotide delivery promotes activity-linked thermogenesis. Mol Ther. 2015;23:707–716. doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu Z, Sierra A, Burnett CM, Chen B, Subbotina E, Koganti SR, Gao Z, Wu Y, Anderson ME, Song LS, Goldhamer DJ, Coetzee WA, Hodgson-Zingman DM, Zingman LV. Sarcolemmal ATP-sensitive potassium channels modulate skeletal muscle function under low-intensity workloads. J Gen Physiol. 2014;143:119–134. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201311063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alekseev AE, Reyes S, Yamada S, Hodgson-Zingman DM, Sattiraju S, Zhu Z, Sierra A, Gerbin M, Coetzee WA, Goldhamer DJ, Terzic A, Zingman LV. Sarcolemmal ATP-sensitive K(+) channels control energy expenditure determining body weight. Cell metabolism. 2010;11:58. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cifelli C, Boudreault L, Gong B, Bercier JP, Renaud JM. Contractile dysfunctions in ATP-dependent K+ channel-deficient mouse muscle during fatigue involve excessive depolarization and Ca2+ influx through L-type Ca2+ channels. Experimental physiology. 2008;93:1126. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2008.042572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cifelli C, Bourassa F, Gariepy L, Banas K, Benkhalti M, Renaud JM. KATP channel deficiency in mouse flexor digitorum brevis causes fibre damage and impairs Ca2+ release and force development during fatigue in vitro. The Journal of physiology. 2007;582:843. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.130955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gong B, Legault D, Miki T, Seino S, Renaud JM. KATP channels depress force by reducing action potential amplitude in mouse EDL and soleus muscle, American journal of physiology. Cell physiology. 2003;285:C1464. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00278.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Light PE, Comtois AS, Renaud JM. The effect of glibenclamide on frog skeletal muscle: evidence for K+ATP channel activation during fatigue. The Journal of physiology. 1994;475:495. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thabet M, Miki T, Seino S, Renaud JM. Treadmill running causes significant fiber damage in skeletal muscle of KATP channel-deficient mice. Physiological genomics. 2005;22:204. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00064.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boudreault L, Cifelli C, Bourassa F, Scott K, Renaud JM. FATIGUE PRECONDITIONING INCREASES FATIGUE RESISTANCE AND REDUCES MUSCLE DEPENDENCY ON K(sub)ATP(/sub) CHANNELS TO PREVENT CONTRACTILE DYSFUNCTIONS IN MOUSE FDB. The Journal of physiology. 2010 doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.191510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flagg TP, Enkvetchakul D, Koster JC, Nichols CG. Muscle KATP channels: recent insights to energy sensing and myoprotection. Physiological Reviews. 2010;90:799. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00027.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spriet LL, Hargreaves M. Overview of exercise metabolism. In: Hargreaves M, Spriet LL, editors. Exercise Metabolism. Human Kinetics; Champaign, IL: 2006. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang S, Soni KG, Semache M, Casavant S, Fortier M, Pan L, Mitchell GA. Lipolysis and the integrated physiology of lipid energy metabolism. Mol Genet Metab. 2008;95:117–126. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Potter LR, Yoder AR, Flora DR, Antos LK, Dickey DM. Natriuretic peptides: their structures, receptors, physiologic functions and therapeutic applications. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009:341–366. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-68964-5_15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Potter LR. Natriuretic peptide metabolism, clearance and degradation. FEBS J. 2011;278:1808–1817. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lafontan M, Moro C, Berlan M, Crampes F, Sengenes C, Galitzky J. Control of lipolysis by natriuretic peptides and cyclic GMP. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2008;19:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Birkenfeld AL, Budziarek P, Boschmann M, Moro C, Adams F, Franke G, Berlan M, Marques MA, Sweep FC, Luft FC, Lafontan M, Jordan J. Atrial natriuretic peptide induces postprandial lipid oxidation in humans. Diabetes. 2008;57:3199–3204. doi: 10.2337/db08-0649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moro C, Pillard F, de Glisezinski I, Klimcakova E, Crampes F, Thalamas C, Harant I, Marques MA, Lafontan M, Berlan M. Exercise-induced lipid mobilization in subcutaneous adipose tissue is mainly related to natriuretic peptides in overweight men. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295:E505–513. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90227.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishikimi T, Iemura-Inaba C, Akimoto K, Ishikawa K, Koshikawa S, Matsuoka H. Stimulatory and Inhibitory regulation of lipolysis by the NPR-A/cGMP/PKG and NPR-C/G(i) pathways in rat cultured adipocytes. Regul Pept. 2009;153:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sengenes C, Berlan M, De Glisezinski I, Lafontan M, Galitzky J. Natriuretic peptides: a new lipolytic pathway in human adipocytes. FASEB J. 2000;14:1345–1351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kita S, Nishizawa H, Okuno Y, Tanaka M, Yasui A, Matsuda M, Yamada Y, Shimomura I. Competitive binding of musclin to natriuretic peptide receptor 3 with atrial natriuretic peptide. J Endocrinol. 2009;201:287–295. doi: 10.1677/JOE-08-0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishizawa H, Matsuda M, Yamada Y, Kawai K, Suzuki E, Makishima M, Kitamura T, Shimomura I. Musclin, a novel skeletal muscle-derived secretory factor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19391–19395. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400066200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas G, Moffatt P, Salois P, Gaumond MH, Gingras R, Godin E, Miao D, Goltzman D, Lanctot C. Osteocrin, a novel bone-specific secreted protein that modulates the osteoblast phenotype. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:50563–50571. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307310200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Subbotina E, Sierra A, Zhu Z, Gao Z, Koganti SRK, Reyes S, Stepniak E, Walsh SA, Acevedo MR, Perez-Terzic C, Hodgson-Zingman DM, Zingman LV. Musclin is an activity-stimulated myokine that enhances physical endurance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America Accepted. 2015 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1514250112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saegusa N, Sato T, Saito T, Tamagawa M, Komuro I, Nakaya H. Kir6.2-deficient mice are susceptible to stimulated ANP secretion: K(ATP) channel acts as a negative feedback mechanism? Cardiovasc Res. 2005;67:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu T, Jiao JH, Pence RA, Baertschi AJ. ATP-sensitive potassium channels regulate stimulated ANF secretion in isolated rat heart. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:H2339–2345. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.6.H2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stitt TN, Drujan D, Clarke BA, Panaro F, Timofeyva Y, Kline WO, Gonzalez M, Yancopoulos GD, Glass DJ. The IGF-1/PI3K/Akt pathway prevents expression of muscle atrophy-induced ubiquitin ligases by inhibiting FOXO transcription factors. Mol Cell. 2004;14:395–403. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00211-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yasui A, Nishizawa H, Okuno Y, Morita K, Kobayashi H, Kawai K, Matsuda M, Kishida K, Kihara S, Kamei Y, Ogawa Y, Funahashi T, Shimomura I. Foxo1 represses expression of musclin, a skeletal muscle-derived secretory factor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;364:358–365. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mihaylova MM, Vasquez DS, Ravnskjaer K, Denechaud PD, Yu RT, Alvarez JG, Downes M, Evans RM, Montminy M, Shaw RJ. Class IIa histone deacetylases are hormone-activated regulators of FOXO and mammalian glucose homeostasis. Cell. 2011;145:607–621. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen TJ, Choi MC, Kapur M, Lira VA, Yan Z, Yao TP. HDAC4 regulates muscle fiber type-specific gene expression programs. Mol Cells. 2015;38:343–348. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2015.2278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tong X, Porter LM, Liu G, Dhar-Chowdhury P, Srivastava S, Pountney DJ, Yoshida H, Artman M, Fishman GI, Yu C, Iyer R, Morley GE, Gutstein DE, Coetzee WA. Consequences of cardiac myocyte-specific ablation of KATP channels in transgenic mice expressing dominant negative Kir6 subunits, American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology. 2006;291:H543. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00051.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zingman LV, Hodgson DM, Bast PH, Kane GC, Perez-Terzic C, Gumina RJ, Pucar D, Bienengraeber M, Dzeja PP, Miki T, Seino S, Alekseev AE, Terzic A. Kir6.2 is required for adaptation to stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:13278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212315199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hodgson DM, Zingman LV, Kane GC, Perez-Terzic C, Bienengraeber M, Ozcan C, Gumina RJ, Pucar D, O’Coclain F, Mann DL, Alekseev AE, Terzic A. Cellular remodeling in heart failure disrupts K(ATP) channel-dependent stress tolerance. The EMBO journal. 2003;22:1732. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsukawa N, Grzesik WJ, Takahashi N, Pandey KN, Pang S, Yamauchi M, Smithies O. The natriuretic peptide clearance receptor locally modulates the physiological effects of the natriuretic peptide system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:7403–7408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sengenes C, Zakaroff-Girard A, Moulin A, Berlan M, Bouloumie A, Lafontan M, Galitzky J. Natriuretic peptide-dependent lipolysis in fat cells is a primate specificity. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;283:R257–265. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00453.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pagano M, Anand-Srivastava MB. Cytoplasmic domain of natriuretic peptide receptor C constitutes Gi activator sequences that inhibit adenylyl cyclase activity. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:22064–22070. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101587200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]