The cholera epidemics of the 19th century forged the way for the sanitation revolution and the provision of safe public water sources that are the hallmark of developed countries. Nevertheless, more than 1 billion people today, including much of the population in Haiti, lack access to improved water supply sources and hence remain vulnerable to epidemics of cholera 1. Through our work with non-governmental organizations and governmental agencies, we have been involved firsthand with the developing response to the cholera epidemic in Haiti. Here, we review the Haitian outbreak in the context of other recent cholera epidemics and discuss on-the-ground strategies for optimizing cholera case management.

Prior to the current epidemic, cholera’s most recent appearance in the Western Hemisphere was in the early 1990s. After being effectively absent from the region for more than a century, cholera re-appeared in Peru in January 1991. The first cluster of patients was identified in a coastal village 80 kilometers north of Lima. By the end of 1991, over 390,000 cases of cholera and more than 4,000 deaths had occurred in 16 countries. Although the ferocity of the outbreak's first year was unmatched, cholera remained endemic in the hemisphere for ten years, with the last reported death in 2001.

From a global perspective, the cholera epidemic of the 1990s in the Western Hemisphere was only one front in an ongoing pandemic of cholera that began in Indonesia in 1961. This is the seventh global pandemic of cholera that has occurred the last 200 years; the causative organism is an El Tor biotype of Vibrio cholerae serogroup O1. This El Tor biotype has been so successful that it has now completely replaced the previously circulating classical biotype. Pulse field gel electrophoresis performed at the CDC indicates that the epidemic strain of V. cholerae in Haiti is similar to the South Asian seventh pandemic El Tor strains 2.

In the wake of the 1991 outbreak, the public health infrastructure was strengthened in many countries of Latin America and the Caribbean. Nevertheless, access to safe water in the hemisphere remains uneven, with Haiti being the most notable example. In 2008, only 12% of Haitians received piped, treated water, and only 17% had access to adequate sanitation 3. January’s earthquake effectively destroyed the already fragile infrastructure in Haiti and left more than a million homeless people living in makeshift encampments, primarily in Port-au-Prince. Concern for the possibility of diarrheal disease outbreaks was high in the aftermath of the earthquake, but no immediate event occurred.

Current outbreak in Haiti

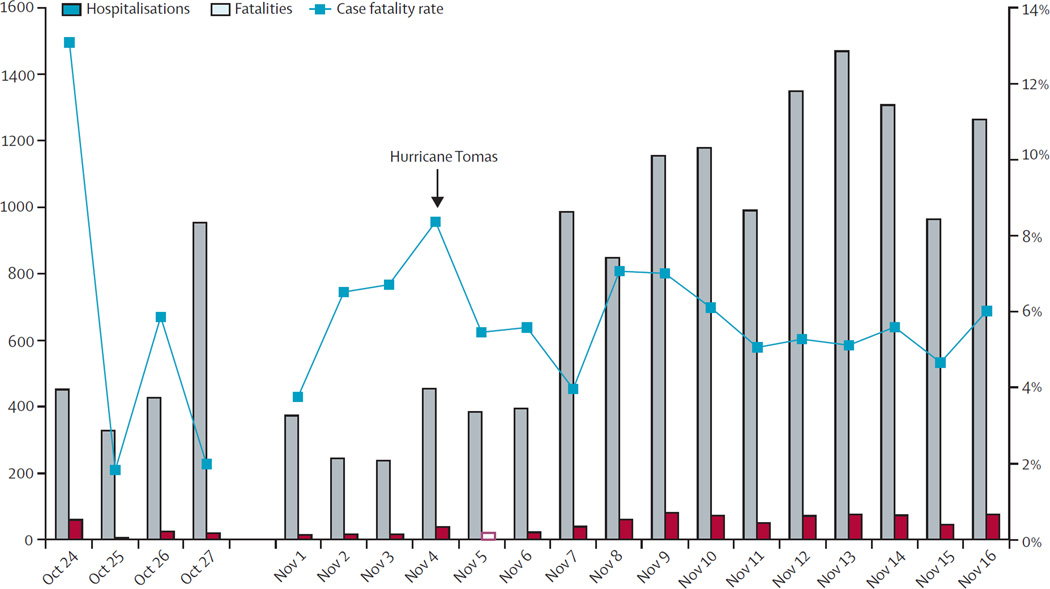

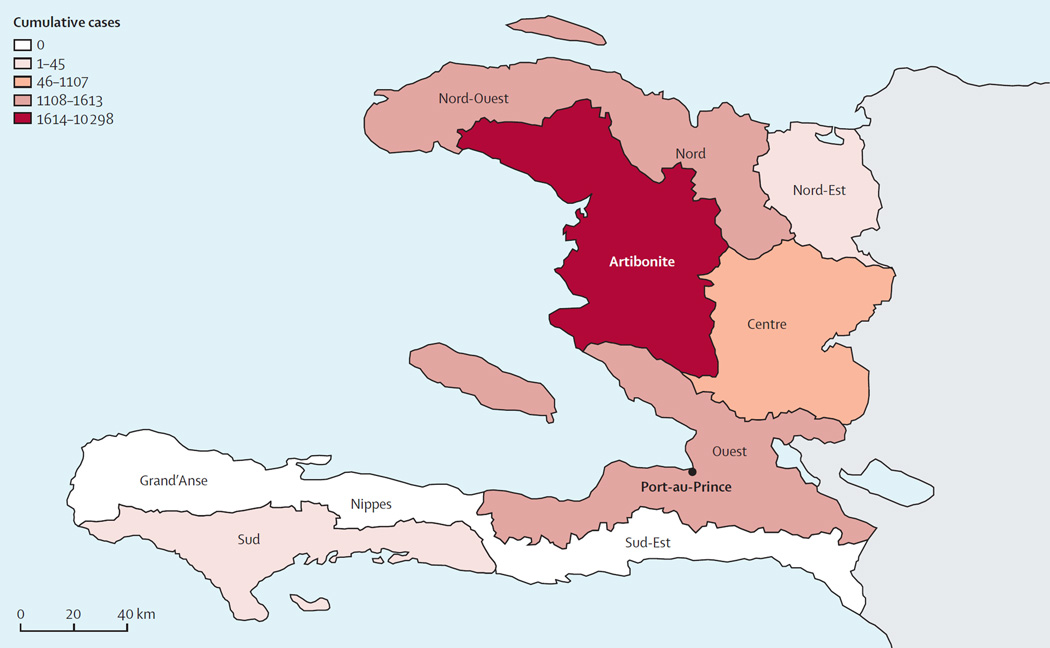

On October 19, an unusually high number of patients with acute watery diarrhea -- predominantly over the age of 5 years -- were identified in the Artibonite and Centre departments. These regions flank the Artibonite River north of Port-au-Prince and are densely settled rural areas that were not heavily affected by the earthquake. The National Public Health Laboratory in Haiti was quick to isolate Vibrio cholerae O1 from stool specimens obtained from patients in the affected area. Cholera has since spread rapidly across the country (Figure 1). As of November 17, a total of 18,382 hospital admissions, and 1,110 deaths due to cholera have been reported 4 (Figure 2). Cases have now been confirmed in 7 of Haiti’s 10 departments, including 953 cases within the capital city of Port-au-Prince. Single cases have also been reported in the neighboring Dominican Republic and in Florida.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Treatment, prevention and control measures are underway in Haiti and have focused on disseminating educational messages on safe water and sanitation practices and the use of oral rehydration solution (ORS). Thirty-two cholera treatment centers have been established within existing health-care institutions and in freestanding locations. The benchmark for assessing the effectiveness of such cholera interventions has long been the case fatality rate; with adequate fluid management, case fatality rates in cholera can be reduced to <1%. At the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research in Dhaka, Bangladesh (ICDDR,B), which played a critical role in the development of ORS and where there is extensive experience managing patients with severe diarrhea, case fatality rates are less than 0.2% 5, 6. In the early stages of the epidemic in Haiti, the case fatality rate of cholera remains at 6% (Figure 2).

Case fatality rates as a benchmark in cholera outbreaks

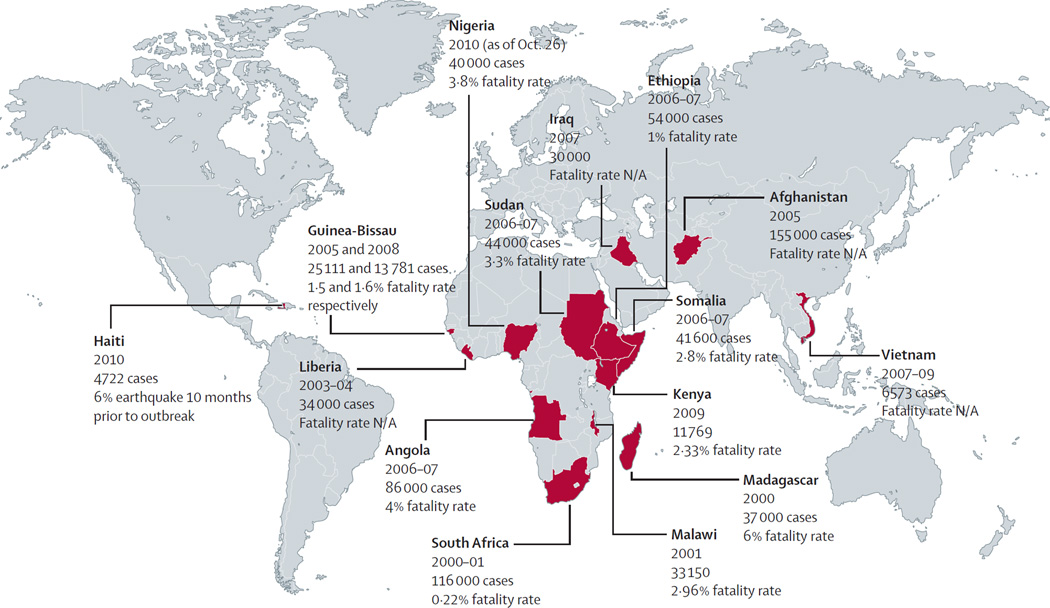

Why has it been difficult to achieve this benchmark of cholera management in Haiti? A look at the recent history of cholera outbreaks within the last 10 years shows that case fatality rates of 1% or less are in fact only rarely achieved in outbreak settings (Figure 3). In the 2008–2009 Zimbabwe cholera outbreak that involved nearly 100,000 people, the case fatality rate was 4.3%. In Angola’s 2006–2007 outbreak, the case fatality rate was similarly high at 4%. Among African nations with cholera, only South Africa, which has a more developed health infrastructure, was able to achieve the benchmark of <1% in its 2000–2001 outbreak. In the Western Hemisphere, case fatality rates reached 5% or higher in the weeks following the emergence of cholera in Peru in 1991. Although an overall case fatality rate of 0.34% was ultimately achieved, rates remained as high as 3% in the less developed mountainous and jungle areas of Peru throughout the epidemic.

Figure 3.

There are inherent biological and organizational challenges to achieving low case fatality rates during a cholera outbreak. Most importantly, the difficulties of providing medical care during a complex emergency must be overcome. From a biological perspective, infection with the organism yields protective immunity, and hence cholera may cause more explosive outbreaks in a naïve population than in a population living in a cholera endemic area like South Asia. Host genetic factors, including the O blood group, predispose individuals to severe cholera and differ in prevalence between populations in endemic and non-endemic areas.

Optimizing cholera case management

Rehydration is the essence of the treatment of cholera. Because of the profoundly rapid fluid losses seen in cholera, achieving optimal fluid management can be a challenge for health care providers who are not familiar with the disease. Death may occur because the initial dehydration status is underestimated and/or because ongoing fluid losses are underappreciated. For these reasons, optimal case management requires an efficient triage system and frequent monitoring of patients. For patients presenting with severe dehydration, isotonic fluids (preferably Lactated Ringer’s solution) should be given as quickly as possible, often through multiple sites of intravenous access, until an easily palpable pulse is restored. The remaining fluid deficit should be replaced within the first four hours after presentation, and ongoing fluid losses need to be factored in. Patients with severe cholera require an average of 200 mL/kg of isotonic fluids in the first 24 hours of therapy, but the amount may range from 100 mL/kg to over 350 mL/kg 7. Patients who present without severe dehydration can usually be treated successfully with oral rehydration solution (ORS), an inexpensive and highly effective treatment that prevents complications of unnecessary intravenous therapy and also conserves resources for more severe cases.

A number of key resources outlining the appropriate management of cholera patients are freely available (Table 1). These range from simple pocket-cards to comprehensive publications regarding the management of diarrheal illness and its complications. To achieve the <1% case fatality benchmark, it is essential that health care workers responding to cholera outbreaks be familiar with the assessment of dehydration, patient triage, and rapid oral and intravenous rehydration strategies that are outlined in these publications. Educating health care providers about rehydration strategies has been an important focus of response efforts in Haiti. Along these lines, the ICDDR, B team is working with the Haitian Ministry of Health (MSPP) on a “training of the trainers (TOTS)” program.

Table 1.

Essential and freely-available resources for training in cholera case management

| Title of Publication | Source | Comments | Weblink |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Steps for Managing an Outbreak of Acute Diarrhoea | World Health Organization | Pocket card | 8 |

| The Cholera Outbreak Training and Shigellosis (COTS) program | ICDDR,B | Manual for training all health care personnel involved in response to diarrheal outbreak | 9 |

| The Treatment of Diarrhoea: A Manual for Physicians and Other Senior Health Workers | World Health Organization | Essential information for physicians regarding treatment of diarrhea | 7 |

In addition to the challenges associated with fluid management, there are many misconceptions about the appropriate use of antibiotics during cholera outbreaks. Antibiotics for cholera shorten the course of diarrheal illness and reduce the volume of diarrheal stool output by up to 50% 10, 11. Antibiotics do not improve mortality from cholera under circumstances of optimal fluid management. However, in the setting of an epidemic, antibiotics likely save lives because they result in the quicker resolution of illness and the more rapid discharge of patients--both of which are essential for freeing up resources in an outbreak setting. Antibiotics also reduce the duration of shedding of infectious organisms in the stool from several days to approximately one day, which has significant public health implications 12. During an epidemic, antibiotics should therefore be given to all patients with severe illness as soon as possible upon presentation.

The current circulating strain in Haiti has been shown to be susceptible to doxycycline and azithromycin and resistant to nalidixic acid, with reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin 2. Based on prior experience, these results suggest that ciprofloxacin is likely to be less effective against this strain 10. Table 2 shows appropriate antibiotic choices for the management of cholera in Haiti. Antibiotics are not indicated for mass chemoprophylaxis against cholera or for cases of mild illness.

Table 2.

Antibiotic choices for the management of cholera in Haiti

| Antibiotic | Older children and adults |

Child | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred antibiotics | |||

| Doxycycline | 300 mg single dose | 4–6 mg/kg single dose |

|

| Azithromycin | 1g single dose | 20 mg/kg single dose |

|

| Alternative antibiotics | |||

| Tetracycline | 500 mg every 6 hours for 3 days | 50 mg/kg/day divided every 6 hours for 3 days |

|

| Erythromycin | 250 mg every 6 hours for 3 days | 40 mg/kg/day divided every 6 hours for 3 days | |

Reducing Disease Transmission

Access to safe drinking water and adequate sanitation systems are essential to the control of cholera, but these are solutions that are implemented in the longer term. In the midst of an outbreak, point-of-use water purification, preferably with chlorine, should be employed. Building latrines is a high priority; pit latrines should be located at least 30 meters from any groundwater source. Educational messages about hand washing with soap, safe food handling and safe funeral practices should be shared with the community. In hospital settings, cot disinfection with 0.05% bleach solutions can prevent nosocomial spread of disease.

For many years, concern has existed that cholera vaccination during epidemics might detract from other control measures such as case management, treatment of drinking water, and sanitation measures. However, several developments have occurred in recent years that are changing thoughts about cholera vaccination. A reanalysis of a large field trial in Bangladesh showed that oral cholera vaccines confer significant herd immunity; vaccinating >51% of the population in a geographic area led to a substantial reduction in rates of cholera among individuals who had not themselves received the vaccine (from 7 per 1000 to less than 1.5 per 1000) 13. A recent analysis of oral cholera vaccination that included this herd immunity effect showed that vaccination in a variety of endemic settings was a cost-effective measure, likely to compare favorably with water and sanitation interventions 14. This cost-effectiveness model assumed a case fatality rate of 1%. Experience over the past decade indicates that case fatality rates during cholera outbreaks are generally sustained above 5% (Figure 3) -- suggesting that the potential cost-benefit ratio of vaccination in such settings could be greater. Furthermore, oral cholera vaccines are now being produced in India and Vietnam at substantially lower costs.

Earlier this year, the World Health Organization modified its position paper on cholera vaccination in response to these emerging data 15. The use of cholera vaccines is now recommended in areas where the disease is endemic and should be considered in areas at risk for outbreaks, a strategy known as pre-emptive vaccination. Pre-emptive vaccination requires the existence of a substantial stockpile of vaccine, which is not presently available. The value of reactive vaccination to halt an ongoing epidemic is less clear. However, with the capacity to produce lower-cost cholera vaccines, there is now an opportunity to develop supplies of cholera vaccine that are sufficient to evaluate and possibly implement vaccination during complex emergencies and outbreaks like the current one in Haiti.

Looking ahead

Because of cholera, the public health landscape of the Western Hemisphere has now changed suddenly and dramatically. Spread of the disease beyond the borders of Haiti in the coming months seems nearly certain, and the organism may well re-establish itself in the region for years to come. In recent days, much attention has focused on the potential source of this outbreak strain. Although the answer to that specific question may or may not come, history has shown us that cholera will eventually find its way to places where societal infrastructure has broken down. In the short term, efforts will continue to focus on education, case management and disease prevention measures, with the aim of lowering cholera case fatality rates closer to the desired benchmark. In the long term, substantial improvements in water quality and sanitation for Haiti will be needed before reliable interruption of cholera transmission can occur.

The dark shadow of cholera has provided the impetus for remarkable change in the past. It is our hope that this latest threat for the people of Haiti may represent a turning point in their quest for access to the most basic of human needs -- safe water.

Acknowledgments

JBH and RC worked in Haiti with Project Hope. RNM, AIK, and PKB worked in Haiti with Project Hope, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Pan American Health Organization. ICDDR,B is supported in its core activities by the governments of Australia, Bangladesh, Canada, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.World Health Statistics 2010. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Update: Cholera Outbreak --- Haiti, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(45):1473–1479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Progress on Sanitation and Drinking Water: 2010 Update. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Epidemiological Alert: Update on the Situation in Haiti. Pan American Health Organization; 2010. Nov 17, [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryan ET, Dhar U, Khan WA, Salam MA, Faruque AS, Fuchs GJ, et al. Mortality, morbidity, and microbiology of endemic cholera among hospitalized patients in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;63(1–2):12–20. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.63.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sack DA, Sack RB, Chaignat CL. Getting serious about cholera. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(7):649–651. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. The treatment of diarrhoea, a manual for physicians and other senior health workers. -- 4th revision. WHO/FCH/CAH/05.1. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. ( http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2005/9241593180.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- 8.First steps for managing an outbreak of acute diarrhea. World Health Organization; 2004. ( http://www.who.int/cholera/publications/first_steps/en/index.html) [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Cholera Outbreak Training and Shigellosis (COTS) program. ( www.path.org/vaccineresources/details.php?i=736)

- 10.Saha D, Karim MM, Khan WA, Ahmed S, Salam MA, Bennish ML. Single-dose azithromycin for the treatment of cholera in adults. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(23):2452–2462. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hossain MS, Salam MA, Rabbani GH, Kabir I, Biswas R, Mahalanabis D. Tetracycline in the treatment of severe cholera due to Vibrio cholerae O139 Bengal. J Health Popul Nutr. 2002;20(1):18–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rabbani GH, Islam MR, Butler T, Shahrier M, Alam K. Single-dose treatment of cholera with furazolidone or tetracycline in a double-blind randomized trial. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33(9):1447–1450. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.9.1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ali M, Emch M, von Seidlein L, Yunus M, Sack DA, Rao M, et al. Herd immunity conferred by killed oral cholera vaccines in Bangladesh: a reanalysis. Lancet. 2005;366(9479):44–49. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66550-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeuland M, Cook J, Poulos C, Clemens J, Whittington D DOMI Cholera Economics Study Group. Cost-effectiveness of new-generation oral cholera vaccines: a multisite analysis. Value Health. 2009;12(6):899–908. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cholera vaccines: WHO position paper. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2010;85(13):117–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]