Abstract

Successful embryo implantation requires functional luminal epithelia to establish uterine receptivity and blastocyst-uterine adhesion. During the configuration of uterine receptivity from prereceptive phase, the luminal epithelium undergoes dynamic membrane reorganization and depolarization. This timely regulated epithelial membrane maturation and precisely maintained epithelial integrity are critical for embryo implantation in both humans and mice. However, it remained largely unexplored with respect to potential signaling cascades governing this functional epithelial transformation prior to implantation. Using multiple genetic and cellular approaches combined with uterine conditional Rac1 deletion mouse model, we demonstrated herein that Rac1, a small GTPase, is spatiotemporally expressed in the periimplantation uterus, and uterine depletion of Rac1 induces premature decrease of epithelial apical-basal polarity and defective junction remodeling, leading to disrupted uterine receptivity and implantation failure. Further investigations identified Pak1-ERM as a downstream signaling cascade upon Rac1 activation in the luminal epithelium necessary for uterine receptivity. In addition, we also demonstrated that Rac1 via P38 MAPK signaling ensures timely epithelial apoptotic death at postimplantation. Besides uncovering a potentially important molecule machinery governing uterine luminal integrity for embryo implantation, our finding has high clinical relevance, because Rac1 is essential for normal endometrial functions in women.

The implantation of the blastocyst into the maternal uterus is a crucial step in establishing pregnancy and thus ensuring further embryonic development.1, 2, 3 Similar to many developmental processes, implantation involves an intricate succession of molecular and cellular interactions which must be executed within an optimal time frame. During this period, the acquisition of blastocyst implantation competency is synchronized with the establishment of uterine receptivity.4, 5, 6 On the basis of previous findings, uterine sensitivity to implantation-competent blastocysts is classically divided into three stages: pre-receptive, receptive and refractory phases.7 In mice, prior to day 4 of pregnancy, the uterus is conventionally considered as the pre-receptive phase. On day 4 and beyond, the uterus becomes fully receptive following the priming actions of ovarian progesterone and preimplantation estrogen; whereas by late day 5, the uterus becomes refractory to initiate the implantation.2, 4, 8

Upon entering the receptive phase, uterine luminal epithelium undergoes dynamic transformation. For example, on day 4 morning in mice, luminal epithelial cells cease proliferation under the dominance of increasing levels of ovarian progesterone and preimplantation estrogen. Meanwhile, the epithelial cells undergo differentiation, accompanied with a dynamic junction complex remodeling and membrane maturation, leading to a decrease of epithelial polarity approaching implantation and a cell-shape transition from columnar to cubical configuration,9 thus gradually achieving the capacity for blastocyst attachment on day 4 evening.10 Therefore, a timely regulated epithelial membrane maturation and precisely maintained epithelial integrity is critical for embryo implantation. In this respect, recent studies have demonstrated that several transcription factors and signaling molecules, such as Msx1, KLF5, Wnt5a, Stat3 and FGFR2 are essential regulators during uterine epithelial transformation into receptivity.5, 11, 12, 13 However, it remained largely unexplored regarding the potential signaling cascades directing the dynamic uterine epithelial membrane differentiation and maturation prior to implantation.

Once upon attachment, the epithelium surrounding the implanting blastocyst undergoes apoptosis triggered by blastocyst-derived signals, which is essential for trophoblast invasion and penetration afterwards.14 There is early evidence that Caspase 3 is an executor of uterine epithelial apoptotic death and loss of Klf5 in mice leads to impaired epithelial cell elimination at postimplantation.5, 15 However, it remained largely elusive regarding the underlying mechanisms governing luminal epithelial cell death after blastocyst-uterus attachment.

Because Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (Rac1), a small GTPase belonging to the 21 kDa Rho-GTPase family,16, 17 is a multifunctional switch involved in epithelial development, differentiation and apoptotic cell clearance in various systems,18, 19,20,21,22 and Rac1 is also involved in regulating human endometrial stromal cell migration in culture,23 we speculated that Rac1 and its driving signaling cascade might be an important player directing normal luminal epithelial integrity conducive to on-time embryo implantation. To address this issue, in the present study, we used a uterine Rac1 conditional deletion mouse model and demonstrated that Rac1 depletion in the uterus induces premature decrease of epithelial apical-basal polarity and defective junction remodeling, hampering normal uterine receptivity and thus on-time embryo implantation.

Results

Rac1 is spatiotemporally expressed in the periimplantation uterus

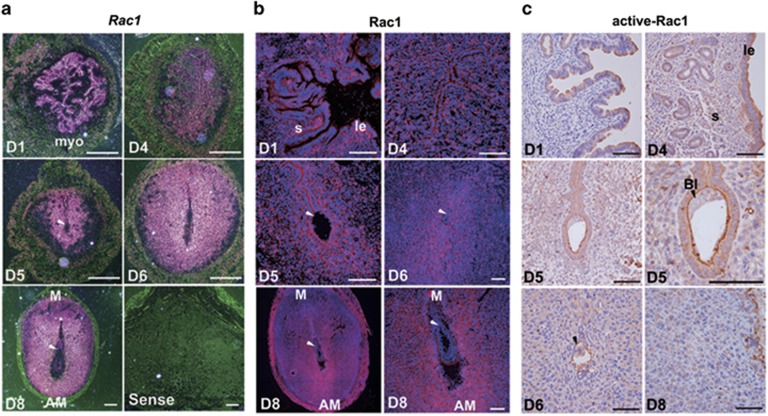

We first performed in situ hybridization and immunostaining experiments to determine the spatiotemporal expression pattern of Rac1 in the uterus at periimplantation in mice. As illustrated in Figure 1, although both Rac1 mRNA and protein were highly detected in the uterine luminal and glandular epithelium on day 1 of pregnancy under the influence of preovulatory estrogen, its expression was visualized in epithelium as well as stroma on day 4, at which the uterine milieu is dominated by a rising level of progesterone produced by the newly formed corpora lutea. With the onset of implantation on day 5, Rac1 expression expanded to the stromal cells surrounding the implanting embryo. It was worthy to note that both total and the GTP-bounded active Rac1 proteins presented a specific localization in the apical side of the epithelium in the receptive uterus on day 4 and in those surrounding the implanting blastocyst on day 5 (Figures 1a and c). This dynamic expression and timely activation of Rac1 signaling is coincident with uterine epithelial differentiation and transformation during embryo-lumen apposition and attachment. Moreover, with the initiation and progression of uterine-decidual transformation on day 6 and beyond, Rac1 was intensely detected in the decidualizing stromal cells (Figures 1a and c), implying its potential involvement in decidual development at postimplantation.

Figure 1.

Rac1 is expressed in the periimplantation mouse uterus in a spatiotemporal manner. (a) In situ hybridization of Rac1 mRNA in D1-8 uteri. The pink site indicates Rac1's location. Positive signals were not detected in the uterus labeled with the Sense probe. myo, myometrium; M, mesometrium; AM, anti-mesometrium. The white arrowhead indicates the embryo. Scale bars, 200 μm. (b) Immunofluorescence of Rac1 protein in D1-8 uteri. Red signals represent Rac1 protein and the nucleus is marked with DAPI. The white arrowhead indicates the embryo. le, luminal epithelium; s, stroma; M, mesometrium; AM, anti-mesometrium. Scale bars, 100 μm. (c) Immunohistochemistry of active Rac1 in D1-8 uteri. The arrowhead indicates the embryo. le, luminal epithelium; s, stroma. Scale bars, 100 μm

Uterine deletion of Rac1 defers on-time implantation compromising term pregnancy success

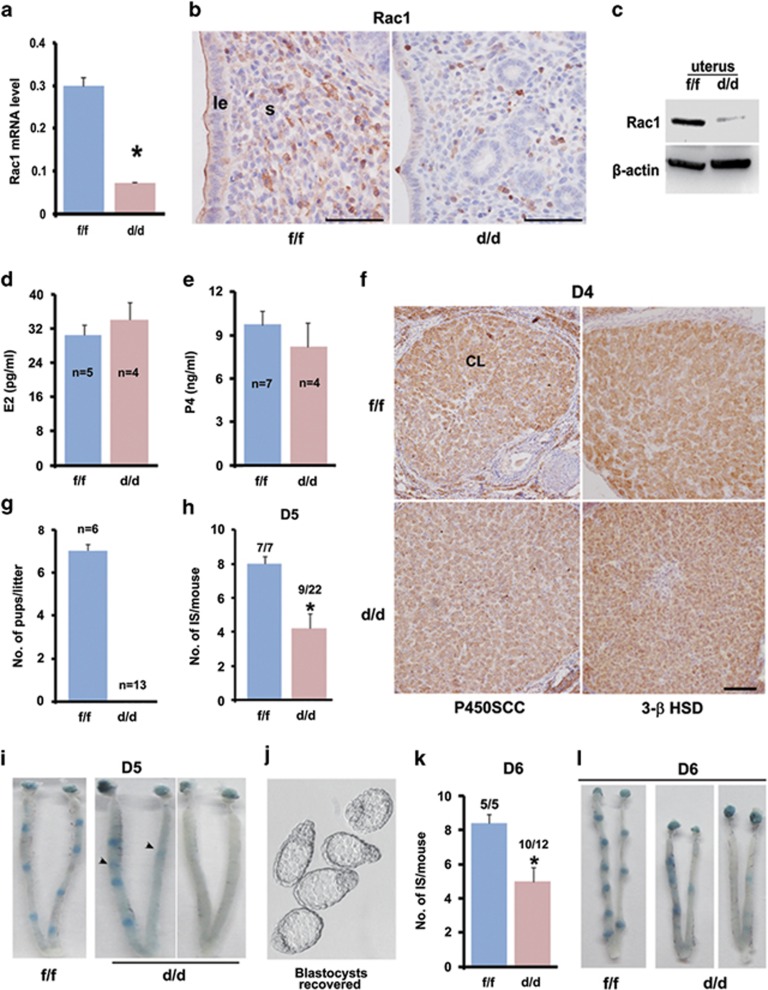

Because the systemic Rac1 null mice are embryonic lethal owing to gastrulation defects,24 to analyze the pathophysiological significance of Rac1 in early pregnancy events, we next used a progesterone receptor (Pgr)-driven Cre (Pgrcre/+) mouse model crossed with Rac1 floxed (Rac1f/f) mice to achieve uterine-selective deletion of Rac1.25, 26, 27 As shown in Figures 2a and c, both Rac1 mRNA and protein were efficiently deleted in Rac1 null (Rac1d/d) uterine epithelia and stroma. Because Pgrcre/+ mouse model can also drive conditional gene loss in the developing corpus luteum, we also analyzed the levels of ovarian steroid secretion and observed that Rac1d/d mouse exhibited comparable circulating levels of progesterone and 17β-estradiol accompanied with normal expression of key steroid biosynthetic enzymes, P450Scc and 3β-HSD in the corpus luteum as those in Rac1f/f female on day 4 of pregnancy (Figures 2d and f). In fact, normal ovulation and fertilization processes were noted in Rac1d/d mice (data not shown). However, we observed with interests that Rac1d/d females were completely infertile even when mated with wild-type (WT) fertile males (Figure 2g).

Figure 2.

Uterine deletion of Rac1 impairs normal embryo implantation resulting in female infertility. (a–c) Detection of Rac1 mRNA and protein level in Rac1f/f and Rac1d/d D4 uteri. *P<0.05. Scale bars, 100 μm. (d, e) Serum levels of E2 and P4 in Rac1f/f and Rac1d/d mice on D4 of pregnancy. (f) Immunohistochemical staining of P450SCC and 3β-HSD in Rac1f/f and Rac1d/d ovaries. Scale bars, 100 μm. (g) Litter sizes in Rac1f/f and Rac1d/d mice. (h, i) Implantation rate, number of implantation sites and representative uteri on D5 in Rac1f/f and Rac1d/d mice. Numerals above bars indicate numbers of dams with implantation sites over total number of dams examined. The black arrowheads indicate the weak blue band in Rac1d/d mice. (j) Embryos recovered from Rac1d/d uterus without signs of blue reaction on day 5. (k, l) Implantation rate, number of implantation sites and representative uteri on D6 in Rac1f/f and Rac1d/d mice. Numerals above bars indicate numbers of dams with implantation sites over total number of dams examined.

To ascertain the stage-specific causes accounting for this obvious infertility, we subsequently analyzed the implantation status in mice missing uterine Rac1. Although all Rac1f/f mice tested showed normal embryo implantation on day 5 morning when visualized by the blue dye method, a large portion (13 out of 22) of Rac1d/d females exhibited implantation failure; whereas the remaining Rac1d/d mice presented a significantly reduced number of implantation sites (Figures 2h and i). Morphologically normal blastocysts were recovered by flushing the Rac1d/d uteri without signs of attachment reaction (Figure 2j). An impaired implantation event could be observed even when analyzed on day 6 of pregnancy (Figures 2k and l). These findings clearly indicated that Rac1 is essential for normal on-time embryo implantation in mice.

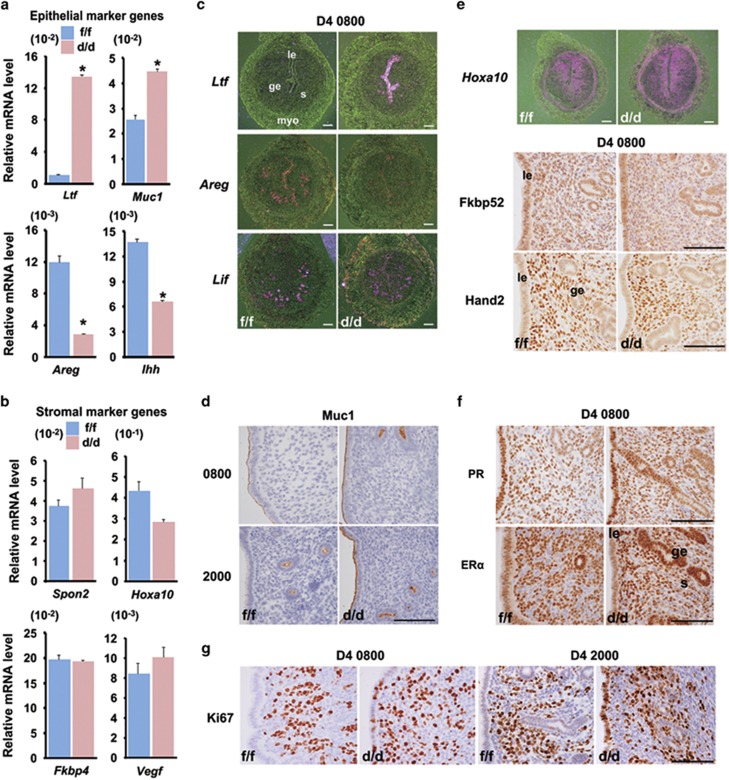

Uterine Rac1 deficiency derails normal epithelial transformation and integrity resulting in impaired uterine receptivity and embryo implantation

To elucidate underlying causes of the defective implantation upon uterine Rac1 deficiency, we then examined the expression profile of uterine receptivity marker genes, and noted that uterine Rac1 deficiency largely demolished normal gene expressions in luminal epithelium, but not in stroma at periimplantation (Figures 3a and f). For example, whereas mucin-1 (Muc1) and lactotransferrin (Ltf) were aberrantly induced in Rac1d/d uterine epithelial layer on day 4, the expression of Amphiregulin (Areg) and Indian hedgehog (Ihh) were adversely downregulated in uterine luminal epithelium with a comparable expression of Leukemia inhibitory factor (Lif) in the glandular epithelium (Figures 3a, c and d). However, uterine stromal expression of homeobox A10 (Hoxa10), Hand2, Fkbp52, ERα and PR were comparably detected in both Rac1f/f and Rac1d/d females (Figures 3b, e and f). This derailed expression of uterine receptivity marker genes was well coincident with abnormally enhanced uterine luminal epithelial proliferation instead of differentiation in Rac1d/d females on day 4 when measured by Ki67 immunostaining (Figure 3g). These observations suggested that uterine Rac1 is essential for normal epithelial cell transformation in establishing uterine receptivity.

Figure 3.

Uterine receptivity is disrupted in Rac1d/d uterus. (a, b) Relative expression levels of epithelial genes (a) and stromal genes (b) in Rac1f/f and Rac1d/d D4 uteri. Unpaired t test, *P<0.05. (c–e) In situ hybridization and immunostaining of epithelial and stromal marker genes in Rac1f/f and Rac1d/d D4 uteri. (f) Expression of ERα and PR receptors in Rac1f/f and Rac1d/d D4 uteri. (g) Ki67 staining in Rac1f/f and Rac1d/d uteri at D4 morning (0800 h) and evening (2000 h). le, luminal epithelium; ge, glandular epithelium; s, stroma; myo, myometrium. Scale bars, 100 μm

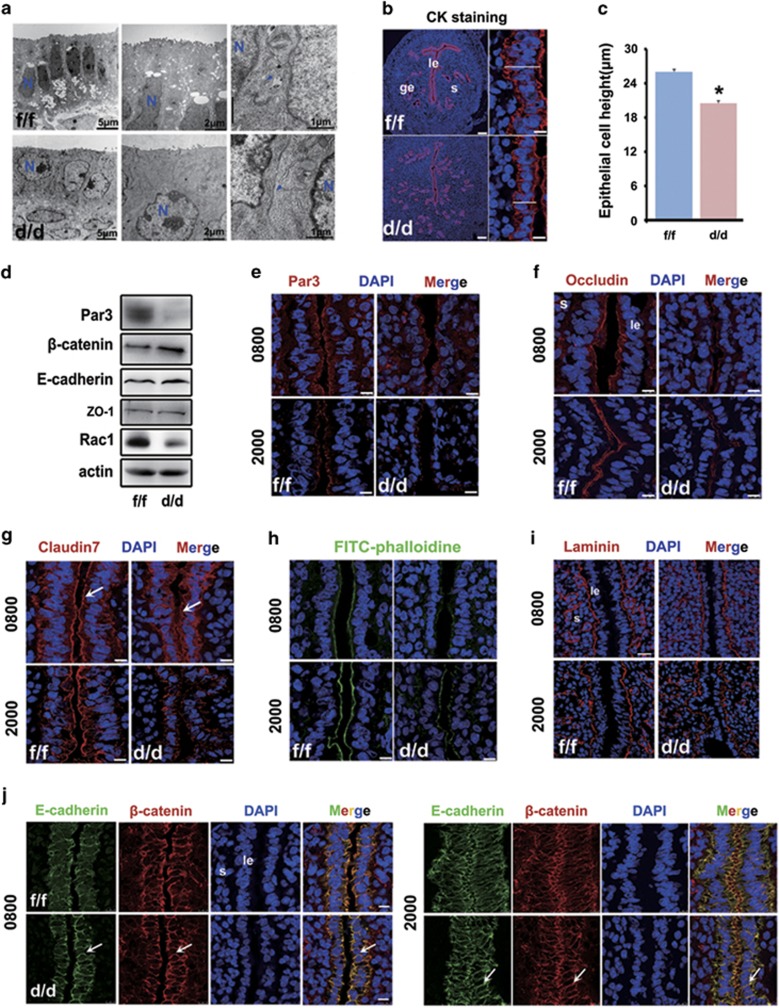

Because uterine luminal epithelial transformation involves dynamic reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton,28 and that Rac1 has been shown to be involved in orchestrating cell shape remodeling,20, 21, 29 we speculated that uterine Rac1 deficiency would impair the functional integrity of the luminal epithelia at periimplantation. Indeed, electron microscopy analysis revealed a dramatic cell shape difference between the Rac1f/f and Rac1d/d luminal epithelia on day 4, showing columnar and thicker Rac1f/f epithelial cells but cuboidal Rac1d/d epithelial cells (Figure 4a). Moreover, while the number of microvilli in the apical cell surface of Rac1d/d epithelium was much less than that in Rac1f/f epithelium, the lateral cell borders and thus cell-cell adhesion were more condensed in the Rac1d/d epithelium (Figure 4a). Cytokeratin labelling experiment and quantification of apical-to-basal cell height measurement further proved the epithelial cell shape perturbation upon Rac1 depletion (Figures 4b and c), pointing toward the fact that uterine Rac1 deficiency hampers the epithelial integrity prior to embryo implantation. Next, we explored the dynamic junction remodeling of epithelial cell in both Rac1f/f and Rac1d/d uteri.

Figure 4.

Uterine epithelial transformation prior to implantation is disrupted in Rac1d/d mice. (a) Representative TEM pictures in Rac1f/f and Rac1d/d D4 uteri. N, cell nucleus. The blue arrowhead indicates cell-cell junction. (b, c) Measurement of luminal epithelial cell height by cytokeratin immunostaining in Rac1f/f and Rac1d/d D4 uteri. *P<0.05. The white line marks the length of the epithelium from basal to apical membrane. Scale bars for represents 100 and 10 μm, respectively. (d) Western blot detection of Par3, β-catenin, E-cadherin and ZO-1 in Rac1f/f and Rac1d/d D4 uteri. (e–h) Immunofluorescence localization of apical markers Par3, Occludin, Claudin 7 and F-actin in Rac1f/f and Rac1d/d uteri at D4 morning (0800 h) and evening (2000 h). The white arrowheads indicate apical staining in the luminal epithelium cells. Scale bars, 10 μm. (i) Immunostaining of basal membrane marker Laminin in Rac1f/f and Rac1d/d D4 uterus. Scale bars, 25 μm. (j) Immunofluorescence of adherens junction molecules E-cadherin and β-catenin in Rac1f/f and Rac1d/d D4 uteri. The white arrowheads indicate lateral membrane of the luminal epithelium cells. Scale bars, 10 μm. le, luminal epithelium; ge, glandular epithelium; s, stroma

As shown in Figures 4d and f, both Par3 and Occludin expression were remarkably reduced in the apical surface of Rac1d/d epithelium on day 4 of pregnancy. Moreover, while Claudin 7 was comparably expressed in the basolateral surface in both WT and Rac1 null epithelium, its prominent expression in the apical membrane of epithelial cells disappeared in the absence of uterine Rac1 (Figure 4g). Similar reduced apical F-actin localization was also noted in Rac1 null epithelium on day 4 of pregnancy (Figure 4h). These findings indicated a premature decrease of epithelial apical-basal polarity upon Rac1 depletion. However, the basal lamina appeared to be unaltered in the Rac1d/d epithelial cells (Figure 4i). In contrast to key tight junction components, the adherens junction molecules E-cadherin and β-catenin exhibited a slightly increased expression in Rac1d/d epithelium (Figure 4d). Interestingly, the lateral E-cadherin expression tended to be more prominent in Rac1d/d epithelium in comparison with Rac1f/f epithelium (Figure 4j). These results reinforced the concept that Rac1 is essential for proper plasma membrane differentiation during epithelial transformation for uterine receptivity and implantation.

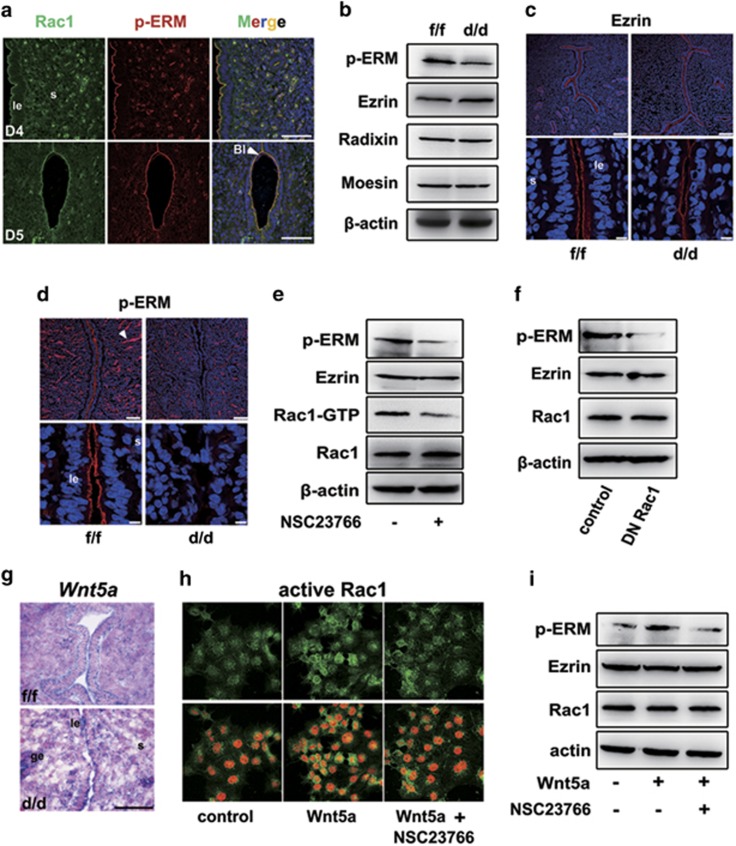

Uterine Rac1 deficiency abolishes Pak1-ERM activation, compromising luminal epithelial integrity

Because Ezrin-Moesin-Radixin (ERM) proteins are general cross-linkers between cortical actin filaments and plasma membranes essential for apical differentiation,30, 31, 32, 33 and that they are highly expressed in the uterine epithelium at periimplantation,34 we next explored whether ERM signaling would take part in uterine epithelial transformation upon Rac1 activation. As shown in Figure 5a, Rac1 and p-ERM (active ERM) were well colocalized in the apical side of uterine luminal epithelium on days 4 and 5 of pregnancy, indicating the possibility that ERM activation may mediate Rac1's function during epithelial transformation. Indeed, while the total levels of ERM were comparably expressed in both Rac1f/f and Rac1d/d uterus (Figures 5b and c), Rac1 deficiency largely abolished ERM phosphorylation in the epithelium (Figures 5b and d). It was noteworthy that the active p-ERM was normally detected in blood vessel endothelium even in Rac1d/d uteri (Figure 5d).

Figure 5.

ERM signaling is disrupted in Rac1d/d uteri. (a) Colocalization of Rac1 and p-ERM in Rac1f/f D4-5 uteri visualized by immunofluorescence staining. The white arrowhead indicates blastocyst. Scale bars, 50 μm. (b–d) Detection of p-ERM, Ezrin, Radixin and Moesin by western blot and immunofluorescence staining in Rac1f/f and Rac1d/d D4 uteri. The white arrowhead indicates blood vessel endothelium. Scale bars represent 100 and 10 μm, respectively. (e) Immunoblot analysis of p-ERM, Ezrin and Rac1 in Ishikawa uterine epithelial cells treated with 100 μM Rac1 inhibitor NSC23766 for 24 h. Actin serves as a loading control. (f) Western blot analysis of p-ERM, Ezrin and Rac1 in Ishikawa cells transfected with either the empty vector or dominant negative Rac1 (Rac1N17) constructs. Actin serves as a loading control. (g) In situ detection of Wnt5a in Rac1f/f and Rac1d/d mice. (h) Immunofluorescence detection of active Rac1 after Wnt5a and/or NSC23766 treatment. Scale bars, 50 μm. (i) Immunoblot analysis of Ishikawa cells treated with Wnt5a and/or NSC23766 for 24 h. Whole-cell lysates were blotted for p-ERM, Ezrin and Rac1. Actin serves as a loading control. le, luminal epithelium; s, stroma

To clarify the signaling cascade between Rac1 activation and ERM phosphorylation, we used a Rac1 inhibitor NSC23766 in uterine Ishikawa epithelial cells, and found that Rac1 inhibition could greatly abolish ERM phosphorylation (Figure 5e). Similar observations could be achieved when the Ishikawa cells were transfected with a dominant negative Rac1 (N17Rac1)26 (Figure 5f). Because Rac1 is a known target of Wnt5a signaling35, 36 that has been shown to be essential for cell polarity induction and epithelial function in various organs including the uterus,9, 11, 37 we also analyzed the consequence of Rac1 deficiency on uterine Wnt5a expression. As shown in Figure 5g, Wnt5a was comparably expressed in both Rac1f/f and Rac1d/d luminal epithelia. However, although recombinant Wnt5a protein facilitated p-ERM activation via its noncanonical Rac1 pathway, Rac1 inhibition by NSC23766 could significantly block Wnt5a-stimulated Rac1 activation and thus ERM phosphorylation (Figures 5h and i). These findings collectively indicated that ERM signaling is a downstream effector of Rac1 in maintaining epithelial architecture. However, it remained to answer how active Rac1 regulates ERM phosphorylation.

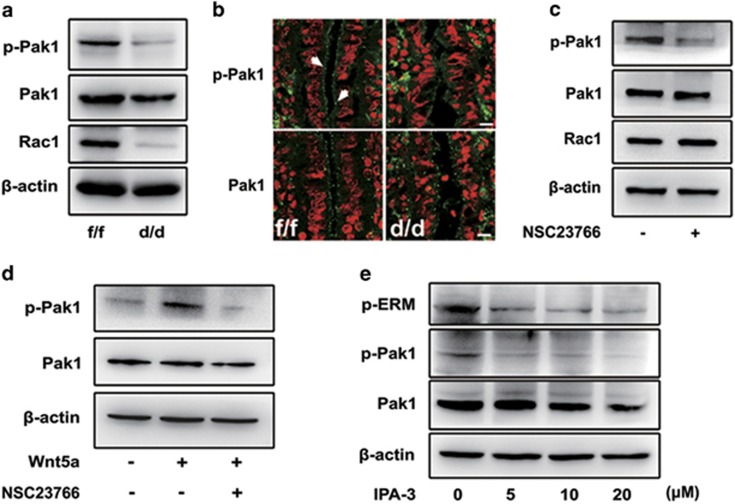

To address this issue, we further analyzed the expression of P21 activated kinase 1 (Pak1), a serine/threonine kinase known as a major downstream effector of Rac1 activation. In line with above-mentioned p-ERM inhibition upon Rac1 loss (Figures 5b and d), we also found that p-Pak1 was significantly downregulated in Rac1d/d uteri (Figures 6a and b). In cultured Ishikawa epithelial cells, Rac1 inhibition by NSC23766 could also remarkably reduce Pak1 phosphorylation (Figure 6c). Meanwhile, recombinant human Wnt5a protein significantly increased Pak1 phosphorylation, and this effect could be blocked by the addition of Rac1 inhibitor NSC23766 (Figure 6d), which was similar to the regulation of Wnt5a on p-ERM expression (Figure 5i). We then asked whether Pak1 activation would directly influence ERM phosphorylation. As indicated in Figure 6e, we indeed observed that Pak1 phosphorylation was inhibited by IPA-3, a cell-permeable allosteric inhibitor that can also remarkably diminish ERM phosphorylation in Ishikawa cells, reinforcing the content that Rac1 functions through Pak1 regulating ERM activation.

Figure 6.

Pak1 activation is inhibited in Rac1d/d luminal epithelium. (a, b) Western blot and immunostaining of p-Pak1 and Pak1 in the uterus of Rac1f/f and Rac1d/d mice. Actin serves as a loading control. White arrowheads indicate the positive signaling of p-Pak1. (c) Immunoblot analysis of p-Pak1, Pak1 and Rac1 in Ishikawa cells treated with Rac1 inhibitor NSC23766 for 24 h. Actin serves as a loading control. (d) Immunoblot analysis of Ishikawa cells treated with Wnt5a and/or NSC23766 for 24 h. Whole-cell lysates were blotted for p-Pak1 and Pak1. Actin serves as a loading control. (e) Immunoblot analysis of p-ERM, p-Pak1 and Pak1 in Ishikawa cells treated with various doses of Pak1 inhibitor IPA-3 for 24 h. Actin serves as a loading control

Rac1d/d luminal epithelium within the implantation chamber fails to undergo apoptotic death at postimplantation

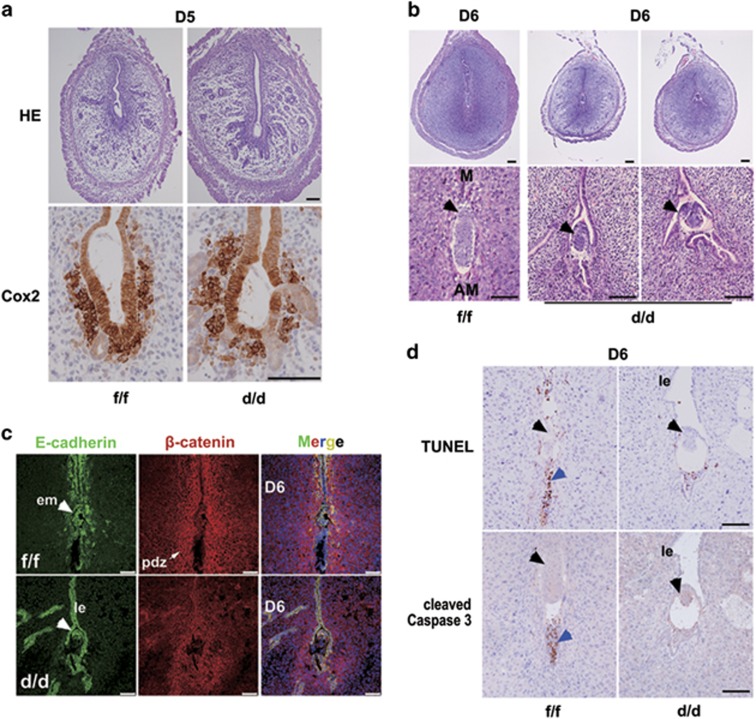

We then asked the question whether an impaired epithelial transformation would lead to premature epithelial apoptotic death at periimplantation. No obvious apoptotic cell death was noted in Rac1d/d epithelium on day 4 of pregnancy (data not shown). Moreover, we observed an apparently normal expression of cyclooxygenase 2 (Cox2) in those Rac1 null females showing blue reaction on day 5 morning (Figure 7a). However, to our surprise, the epithelial layer surrounding the implanting embryo in Rac1d/d females failed to undergo timely degeneration (Figures 7b and c). It is conceivable that an appropriate epithelial transformation is not only essential for ensuring uterine receptivity, but also required for its apoptotic disintegration in response to the invading blastocyst after implantation. Indeed, we observed obvious apoptotic cell clearance in Rac1f/f epithelium, but not in Rac1d/d epithelium via TUNEL assay on day 6 of pregnancy (Figure 7d). Similar expression profile of cleaved Caspase 3 was observed (Figure 7d), further manifesting that Rac1d/d epithelium surrounding the implanting embryo escapes from apoptotic clearance, preventing trophoblast invasion and thus hampers the progression of implantation and embryo development.

Figure 7.

Rac1-deficient luminal epithelium surrounding the implanting embryo fails to undergo apoptotic death at postimplantation. (a) HE and Cox2 staining in Rac1f/f and Rac1d/d D5 implantation sites. Scale bars, 100 μm. (b) Gross histology of Rac1f/f and Rac1d/d implantation sites on D6. M, mesometrium; AM, anti-mesometrium. The black arrowheads indicate embryos. Scale bars, 100 μm. (c) A persisted luminal epithelial layer within the Rac1d/d implantation chambers on D6 visualized by immunofluorescence staining of E-cadherin and β-catenin. The white arrowheads indicate embryos. Scale bars, 75 μm. (d) TUNEL assay and cleaved Caspase 3 staining in Rac1f/f and Rac1d/d day 6 implantation sites. The black arrowheads indicate embryos. The blue arrowhead indicates apoptotic luminal epithelial cells. Scale bars, 100 μm

Rac1 via P38 MAPK signaling ensures timely epithelial apoptotic death at implantation chamber

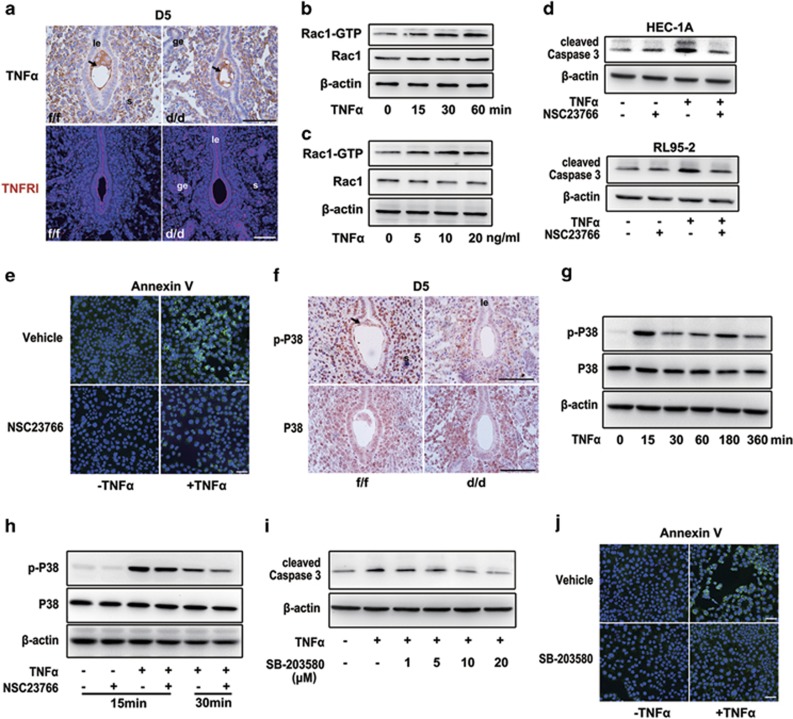

It has been proposed that TNFα may have an essential role in uterine epithelial cell apoptosis.38 Thus, we wondered whether Rac1 could mediate this process. We then analyzed the expression of TNFα and its related receptor TNFRI on day 5 of pregnancy. As shown in Figure 8a, while TNFα protein was highly expressed in the blastocyst and stromal cells underneath the epithelium surrounding the blastocysts, TNFRI was expressed mainly in the epithelium. This cell-specific expression pattern of TNFα and TNFRI pointed toward potential roles of TNFα signaling during epithelial degeneration at postimplantation. Interestingly, we found that TNFα can significantly induce Rac1 activation in a time- and dose-dependent manner in endometrial epithelial cells (Figures 8b and c). This timely induction of Rac1 activation was well associated with increased apoptotic cell death as revealed by cleaved Caspase 3 level in HEC-1 A and RL95-2 epithelial cells treated with recombinant human TNFα protein in culture. Inhibition of Rac1 activity by NSC23766 can block this obvious epithelial cell death upon TNFα challenge (Figures 8d and e).

Figure 8.

Rac1 via P38 MAPK signaling ensures timely epithelial apoptotic death at implantation chamber. (a) Immunostaining of TNFα and TNFRI on Rac1f/f and Rac1d/d D5 implantation sites. le, luminal epithelium; s, stroma; ge, glandular epithelium. Scale bars, 100 μm. The black arrowheads indicate embryos. (b) Time-dependent induction of Rac1-GTP level by 20 ng/ml TNFα in HEC-1A cells. Actin acts as loading control. (c) Dose-dependent induction of Rac1-GTP level after treatment of TNFα for 1 h. Actin acts as loading control. (d) Immunoblot detection of cleaved Caspase 3 in HEC-1A and RL95-2 cells treated with 20 ng/ml TNFα and/or 100 μM NSC23766 for 24 h. Actin acts as a loading control. (e) Immunostaining of Annexin V in HEC-1 A cells treated with 20 ng/ml TNFα and/or 100 μM NSC23766 for 24 h. (f) Immunochemistry of p-P38 and P38 on Rac1f/f and Rac1d/d D5 implantation sites. Scale bars, 100 μm. le, luminal epithelium; s, stroma. The black arrowheads indicate embryos. (g) Time-dependent induction of p-P38 level by 20 ng/ml TNFα. Actin serves as a loading control. (h) Immunoblot detection of p-P38, P38 in HEC-1 A cells treated with 20 ng/ml TNFα and/or 100 μM NSC23766 for 15 min and 30 min. (i) Immunoblot detection of cleaved Caspase 3 in HEC-1A cells treated with 20 ng/ml TNFα and/or 10 μM SB-203580 for 24 h. Actin serves as a loading control. (j) Immunostaining of Annexin V in HEC-1A cells treated with 20 ng/ml TNFα and/or 10 μM SB-203580 for 24 h

As a well-claimed target of TNFα, P38 MAPK signaling is a vital regulatory cascade in cell apoptosis.39, 40 Moreover, Rac1 is a well-defined upregulator of P38 MAPK signaling.41 Thus, we assumed that Rac1 may function through P38 MAPK signaling mediating TNFα-induced uterine epithelial degeneration at postimplantation. Immunostaining analysis revealed that p-P38 was significantly downregulated in Rac1d/d epithelium surrounding the implanting blastocyst (Figure 8f). In HEC-1A cells, whereas TNFα can rapidly induce P38 activation (Figure 8g), a cotreatment of Rac1 inhibitor NSC23766 can efficiently attenuate the induction of P38 phosphorylation in response to TNFα (Figure 8h). Moreover, treatment with P38 inhibitor SB-203580 can significantly reverse the TNFα-induced cell death as reflected by the expression of cleaved Caspase 3 as well as Annexin V staining (Figures 8I and j). Collectively, these results indicated that a timely coordinated TNFα-Rac1-P38 signaling cascade directs epithelial apoptotic degeneration for subsequent embryo invasion at postimplantation.

Discussion

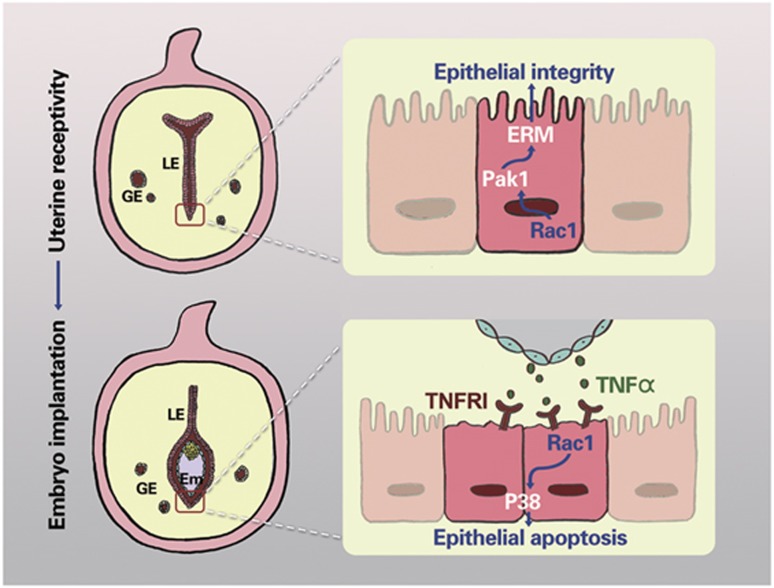

During the prereceptive to receptive transition, uterine luminal epithelium ceases proliferation and gradually initiates differentiation undergoing dynamic membrane reorganization, which is essential for successful implantation in both humans and animal models.3, 42, 43, 44 In the present study, using multiple genetic and cellular approaches combined with uterine conditional Rac1 depletion mouse model, we demonstrated that uterine Rac1 via Pak1-ERM signaling cascade ensures normal luminal epithelial integrity conducive to on-time embryo implantation. We also provided evidence that TNFα-Rac1-P38 signaling cascade is essential for uterine luminal epithelium elimination during postimplantation uterine development (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Illustrative model of Rac1's role in uterine epithelial function during embryo implantation. During receptivity establishment, uterine Rac1 via Pak1-ERM signaling cascade ensures normal luminal epithelial integrity conducive to on-time embryo implantation; while during postimplantation uterine development, Rac1 mediates TNFα induced luminal epithelium elimination via P38 MAPK signaling cascade, which is required for trophoblast invasion into the uterine bed

The epithelial plasma membrane transformation is a hallmark event for uterine receptivity acquisition in various species including the humans.44 The columnar luminal epithelium transits to cuboidal shape and microvilli on the apical plasma show a retraction which makes the apical plasma more flat.44, 45, 46, 47 Moreover, tight junction molecules, such as Occludin, ZO-1 and Claudins are dynamically expressed in the periimplantation uterus.48, 49 This timely remodeling of junction complexes under the control of ovarian steroid hormones represents a decreased epithelial apical-basal polarity during uterine receptivity establishment.9, 11, 45 In fact, previous studies have demonstrated a lack of transition of the luminal epithelium from a high to a less apical-basal polar state in the absence of uterine Msx1 and 2 genes hampers blastocyst implantation.9 As a small GTPase, Rac1 has been found crucial in regulating cell shape and epithelial polarity. For example, Rac1 mutant lens placode cells are shorter and more apically restricted than the control cells.20 GTP-bounded active Rac1 is also necessary for the activation of Par-complex-associated signaling to initiate tight junction morphogenesis and epithelial polarization.50, 51 In line with these previous observations, we also found that the length of Rac1d/d epithelium from basal to apical membrane is shorter, and the apical membrane is obviously more flat compared with the Rac1f/f epithelium. Furthermore, the tight junction molecules Par3, Occludin and Claudin 7 are remarkably decreased in the apical membrane of Rac1d/d luminal epithelium. All these results revealed that the features of epithelial apical-basal polarity had been altered. Our findings demonstrated that Rac1 is essential for the dynamic maintenance of epithelial polarity prior to uterus-embryo crosstalk for implantation, and its deficiency induces a premature decreased epithelial apical-basal polarity, hampering on-time embryo implantation. As a matter of fact, there is recent evidence showing that either excessive decrease or maintenance of epithelial polarity upon loss or gain of Wnt5a disrupts uterine epithelial projections, crypt formation and thus normal implantation.11

Localized to the apical surfaces of many epithelia, the ERM proteins are essential for establishing apical identity and architecture across many organisms.31 Previous expression studies have revealed that ERM proteins are spatiotemporally expressed in the implanting mouse uterus and human endometrium,34, 52 suggesting that ERM signaling may participate in constructing the cellular architecture necessary for blastocyst activation and uterine receptivity. Indeed, we noted a distinct inhibition of ERM activation in the epithelium in the absence of uterine Rac1. This is consistent with previous findings that ERM is essential for Rac family protein-induced cytoskeletal configuration and Rac1 can regulate ERM phosphorylation.17, 34, 53, 54, 55 In searching for the intermediate signaling molecule linking Rac1 activation and ERM phosphorylation, we found that Pak1, a serine/threonine kinase is a downstream target of Rac1 activation, accounts for ERM phosphorylation. It has been reported that Pak1 is involved in the phosphorylation activation of merlin, a highly homologous protein to ERM family members.56, 57 There is also ample evidence that Rac1 via PPase takes part in ERM dephosphorylation.54, 58 This differential coupling of Rac1-ERM signaling cascade may participate in diversified cellular response and outcome.

It has been well defined in mice that uterine epithelial cells situated around the blastocyst undergo cell death during the initial phase of implantation in order to facilitate embryo invasion. This luminal epithelial cell death is identified as apoptosis and is executed by Caspase 3, because a Caspase 3 inhibitor N-acetyl-DEVD-CHO inhibits implantation.15 Opposite to our initial assumption that a premature decrease of epithelial polarity in the absence of Rac1 would lead to increased epithelial cell death, we found that Rac1 is essential for timely luminal epithelial degradation within the implantation chamber; its null mutation results in a persistent epithelial layer surrounding the implantation blastocyst even on day 6 of pregnancy. However, unlike previous observations in Klf5 null mice,5 these retained epithelial layers in the Rac1 null implantation chamber is not due to a reduced Cox2 expression. Because the disintegration of epithelial cells lining the implantation chamber is due to apoptosis in response to the invading blastocyst during normal pregnancy,14 our findings suggested an intrinsic defect of Rac1 null epithelium undergoing apoptotic cell death after embryo-uterine attachment, highlighting the necessity of epithelial integrity for the initiation and progression of implantation. In fact, it has been reported that Rac1 is required for apoptotic cell clearance in bronchial epithelial cells and cell death in mammary gland epithelium.18, 19 Besides, we found that Rac1 mediates TNFα-induced uterine epithelial apoptosis via P38 MAPK signaling. TNFα has been demonstrated to be essential for epithelial cell apoptosis and it could upregulate the level of Rac1-GTP in intestinal epithelial cells.38, 59 P38 signaling is also important for luminal epithelial cell apoptosis and P38 is a well-known target of Rac1 molecule.41, 60, 61, 62 Nonetheless, it is conceivable that a tightly regulated TNFα-Rac1-P38 signaling cascade is essential for uterine luminal epithelium clearance during postimplantation uterine development.

In summary, we provided herein multiline of novel evidence showing that Rac1 via Pak1-ERM signaling cascade directs normal epithelial transformation during uterine receptivity. Moreover, its coupling with TNFα-P38 signaling cascade ensures normal epithelial apoptotic elimination at postimplantation. Our findings have high clinical relevance, because Rac1 is essential for normal human endometrial-embryo dialogue as well as implantation,23 and Ezrin has been reported to be mislocalized in the mid-secretory phase in infertile women.63

Materials and Methods

Animals and treatments

Rac1f/f mice were generated as previously described.26, 27 Uterine-specific mutant mice were generated by crossing Rac1f/f mice with PgrCre/+ mice.25 All mice were housed in the animal care facility of the Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, according to the institutional guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals. Female mice were mated with fertile wild-type males to induce pregnancy (vaginal plug=day 1 of pregnancy). Implantation sites were visualized and recorded by routine blue dye method.4 Mouse blood samples were collected on day 4 morning and serum progesterone and 17β-estradiol levels were measured by radioimmunoassay.

Cell culture

The Ishikawa and HEC-1A uterine epithelial cells were maintained at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air in DMEM medium and McCoy's 5 A medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS, respectively. RL95-2 cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS, 10 mM HEPES and 0.5 μg/ml insulin. IPA-3, NSC23766 and human recombinant Wnt5a protein were purchased from Selleckchem (Houston, TX, USA) and R&D system (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Human recombinant TNFα was a product of Sino Biological Inc (Beijing, China) and SB-203580 was obtained from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA, USA). Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used for plasmid transfection experiments in Ishikawa cells according to the manufacturer's instructions.

In situ hybridization

In situ hybridization was performed as previously described.64, 65 Mouse-specific cRNA probes for Rac1, Areg, Muc1, Ltf, Lif, Hoxa-10 and Wnt5a were used for hybridization. Cryosections hybridized with sense probes served as negative controls.

Immunostaining

Immunohistochemistry was performed in 5-μm-thick, 10% neutral buffer formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections using anti-active Rac1 (1 : 500, NewEast Biosciences, Malvern, PA, USA), Rac1 (1 : 500; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), P450SCC (1 : 100, Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX, USA), 3β-HSD (1 : 100, Santa Cruz), Muc1 (1 : 200, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), FKBP52 (1 : 100, Abcam), Hand2 (1 : 200, Santa Cruz), ERα (1 : 100, Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) and PR (1 : 100, Dako), Ki67 (1 : 500, Epitomics, Burlingame, CA, USA), Cox2 (1 : 500, Santa Cruz), TNFα (1 : 500, Bioworld, St. Louis Park, MN, USA), P38 (1 : 100, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), p-P38 (1 : 100, Cell Signaling Technology) and cleaved Caspase-3 (1 : 100, Cell Signaling Technology) antibodies, respectively. TUNEL assay was used to detect apoptotic cells (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). A Histostain-SP Kit (Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology, Beijing, China) was used to visualize the antigen. For immunofluorescence staining, 10 μm-thick, 4% formaldehyde fixed frozen tissue sections were incubated with anti-Rac1 (1 : 500; BD Biosciences), Cytokeratin (1 : 100, Dako), Par-3 (1 : 100, Santa Cruz), Occludin(1 : 100, Abcam), Claudin 7 (1 : 100, Santa Cruz), FITC-conjugated Phalloidin (1:500, Invitrogen), laminin (1 : 100, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), E-cadherin (1:100, Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany), β-catenin (1 : 100, Abcam), Ezrin (1 : 100, Merck Millipore), p-ERM (1 : 100, Epitomics), active Rac1 (1 : 500, NewEast Biosciences), TNFRI (1 : 100, Bioworld), p-Pak1 (1 : 100, ABclonal, Cambridge, MA, USA) and Pak1 (1 : 100, ABclonal) antibodies, respectively. Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit was a product of Beyotime Company (Shanghai, China). Specific secondary antibodies were used to detect the antigen and DAPI were applied to identify cell nucleus. The images were captured by using a Leica (Nussloch, Germany) DM2500 light microscope fitted with a Qimaging Retiga 2000 R camera (Qimaging, British Columbia, Canada). The epithelial cell height was measured from the apical to basal surface indicated by Cytokeratin staining using the ImageJ software.

Western blot analysis

Protein extraction and western blot analysis were performed as described previously.66 Anti-Rac1 (1 : 1000, Santa Cruz), Par-3 (1 : 500, Santa Cruz), E-cadherin (1 : 500, Calbiochem), β-catenin (1 : 500, Abcam), ZO-1 (1 : 500, Abcam), p-ERM (1 : 1000, Cell Signaling Technology), Ezrin (1 : 1000, Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany), Radixin (1 : 1000, Abcam), Moesin (1 : 1000, Millipore), Pak1 (1 : 500, ABclonal), p-Pak1 (1:500, Sangon, Shanghai, China), cleaved Caspase-3 (1 : 1000, Cell Signaling Technology), P38 (1 : 1000, Cell Signaling Technology), p-P38 (1 : 1000, Cell Signaling Technology), β-actin (1 : 3000, Sigma-Aldrich) antibodies were used, respectively. GTP-Rac1 was detected using GST-PAK-Rac1 pull down assay (Merck Millipore). Actin served as a loading control.

Quantitative real-time PCR

A total of 3 μg RNA was used to synthesize cDNA. The expression levels of different genes were validated by real-time PCR analysis using the ABI 7500 sequence detector system (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA). All the real-time PCR experiments were repeated at least three times. The primers for q-PCR were listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Transmission electron microscopy

Uterine tissues were fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde, post-fixed in 1% osmiumtetroxide (OsO4), and embedded in EMbed 812 (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA) for ultrastructural analysis under a Hitachi H-7600 transmission electron microscope (Hitachi High-Technologies America, Inc., Pleasanton, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with the SPSS11.5 program. Comparison of means was performed using the independent-samples Student t-test. The data are shown as means±S.E.M.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in parts by the National Basic Research Program of China (2011CB944400 to HW and XW) and the National Natural Science Foundation (81130009, 81330017 and 81490744 to H.W.).

Glossary

- ERM

Ezrin-Moesin-Radixin proteins

- ER

estrogen receptor

- PR

progesterone receptor

- Cox2

cyclooxygenase 2

- Klfs

the Kruppel-like factors

- Pak1

p21 protein-activated kinase 1

- Rac1

Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- TNFRI

TNFα receptor I

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Cell Death and Differentiation website (http://www.nature.com/cdd)

Edited by M Piacentini

Supplementary Material

References

- Wang H, Dey SK. Roadmap to embryo implantation: clues from mouse models. Nat Rev Genet 2006; 7: 185–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha J, Sun X, Dey SK. Mechanisms of implantation: strategies for successful pregnancy. Nat Med 2012; 18: 1754–1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim HJ, Wang H. Uterine disorders and pregnancy complications: insights from mouse models. J Clin Invest 2010; 120: 1004–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paria BC, Huet-Hudson YM, Dey SK. Blastocyst's state of activity determines the "window" of implantation in the receptive mouse uterus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993; 90: 10159–10162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Zhang L, Xie H, Wan H, Magella B, Whitsett JA et al. Kruppel-like factor 5 (KLF5) is critical for conferring uterine receptivity to implantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012; 109: 1145–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Lin H, Kong S, Wang S, Wang H, Wang H et al. Physiological and molecular determinants of embryo implantation. Mol Aspects Med 2013; 34: 939–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Z, Ran H, Zhang S, Xia G, Wang B, Wang H. Molecular determinants of uterine receptivity. Int J Dev Biol 2014; 58: 147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paria BC, Lim H, Das SK, Reese J, Dey SK. Molecular signaling in uterine receptivity for implantation. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2000; 11: 67–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daikoku T, Cha J, Sun X, Tranguch S, Xie H, Fujita T et al. Conditional deletion of Msx homeobox genes in the uterus inhibits blastocyst implantation by altering uterine receptivity. Dev Cell 2011; 21: 1014–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey SK, Lim H, Das SK, Reese J, Paria BC, Daikoku T et al. Molecular cues to implantation. Endocr Rev 2004; 25: 341–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha J, Bartos A, Park C, Sun X, Li Y, Cha SW et al. Appropriate crypt formation in the uterus for embryo homing and implantation requires Wnt5a-ROR signaling. Cell Rep 2014; 8: 382–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filant J, DeMayo FJ, Pru JK, Lydon JP, Spencer TE. Fibroblast growth factor receptor two (FGFR2) regulates uterine epithelial integrity and fertility in mice. Biol Reprod 2014; 90: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawar S, Starosvetsky E, Orvis GD, Behringer RR, Bagchi IC, Bagchi MK. STAT3 regulates uterine epithelial remodeling and epithelial-stromal crosstalk during implantation. Mol Endocrinol 2013; 27: 1996–2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parr EL, Tung HN, Parr MB. Apoptosis as the mode of uterine epithelial cell death during embryo implantation in mice and rats. Biol Reprod 1987; 36: 211–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Paria BC. Importance of uterine cell death, renewal, and their hormonal regulation in hamsters that show progesterone-dependent implantation. Endocrinology 2006; 147: 2215–2227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aktories K. Bacterial toxins that target Rho proteins. J Clin Invest 1997; 99: 827–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall A. Rho GTPases and the actin cytoskeleton. Science 1998; 279: 509–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juncadella IJ, Kadl A, Sharma AK, Shim YM, Hochreiter-Hufford A, Borish L et al. Apoptotic cell clearance by bronchial epithelial cells critically influences airway inflammation. Nature 2013; 493: 547–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagci H, Laurin M, Huber J, Muller WJ, Cote JF. Impaired cell death and mammary gland involution in the absence of Dock1 and Rac1 signaling. Cell Death Dis 2014; 5: e1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan BK, Lou M, Zheng Y, Lang RA. Balanced Rac1 and RhoA activities regulate cell shape and drive invagination morphogenesis in epithelia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011; 108: 18289–18294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddala R, Chauhan BK, Walker C, Zheng Y, Robinson ML, Lang RA et al. Rac1 GTPase-deficient mouse lens exhibits defects in shape, suture formation, fiber cell migration and survival. Dev Biol 2011; 360: 30–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stappenbeck TS, Gordon JI. Rac1 mutations produce aberrant epithelial differentiation in the developing and adult mouse small intestine. Development 2000; 127: 2629–2642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grewal S, Carver JG, Ridley AJ, Mardon HJ. Implantation of the human embryo requires Rac1-dependent endometrial stromal cell migration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008; 105: 16189–16194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugihara K, Nakatsuji N, Nakamura K, Nakao K, Hashimoto R, Otani H et al. Rac1 is required for the formation of three germ layers during gastrulation. Oncogene 1998; 17: 3427–3433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soyal SM, Mukherjee A, Lee KY, Li J, Li H, DeMayo FJ et al. Cre-mediated recombination in cell lineages that express the progesterone receptor. Genesis 2005; 41: 58–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Tu X, Joeng KS, Hilton MJ, Williams DA, Long F. Rac1 activation controls nuclear localization of beta-catenin during canonical Wnt signaling. Cell 2008; 133: 340–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Filippi MD, Cancelas JA, Siefring JE, Williams EP, Jasti AC et al. Hematopoietic cell regulation by Rac1 and Rac2 guanosine triphosphatases. Science 2003; 302: 445–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CR. The cytoskeleton of uterine epithelial cells: a new player in uterine receptivity and the plasma membrane transformation. Hum Reprod Update 1995; 1: 567–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TK, Hager HA, Francis R, Kilkenny DM, Lo CW, Bader DM. Bves directly interacts with GEFT, and controls cell shape and movement through regulation of Rac1/Cdc42 activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008; 105: 8298–8303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clucas J, Valderrama F. ERM proteins in cancer progression. J Cell Sci 2014; 127: 267–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClatchey AI. ERM proteins at a glance. J Cell Sci 2014; 127: 3199–3204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes SC, Fehon RG. Understanding ERM proteins—the awesome power of genetics finally brought to bear. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2007; 19: 51–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehon RG, McClatchey AI, Bretscher A. Organizing the cell cortex: the role of ERM proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2010; 11: 276–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto H, Daikoku T, Wang H, Sato E, Dey SK. Differential expression of ezrin/radixin/moesin (ERM) and ERM-associated adhesion molecules in the blastocyst and uterus suggests their functions during implantation. Biol Reprod 2004; 70: 729–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenov MV, Habas R, Macdonald BT, He X. SnapShot: Noncanonical Wnt Signaling Pathways. Cell 2007; 131: 1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Orte E, Saenz-Narciso B, Moreno S, Cabello J. Multiple functions of the noncanonical Wnt pathway. Trends Genet 2013; 29: 545–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medrek C, Landberg G, Andersson T, Leandersson K. Wnt-5a-CKI{alpha} signaling promotes {beta}-catenin/E-cadherin complex formation and intercellular adhesion in human breast epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 2009; 284: 10968–10979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pampfer S, Donnay I. Apoptosis at the time of embryo implantation in mouse and rat. Cell Death Differ 1999; 6: 533–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada T, Penninger JM. Mitogen-activated protein kinases in apoptosis regulation. Oncogene 2004; 23: 2838–2849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarubin T, Han J. Activation and signaling of the p38 MAP kinase pathway. Cell Res 2005; 15: 11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo CH, Kim JH. Rac GTPase activity is essential for lipopolysaccharide signaling to extracellular signal-regulated kinase and p38 MAP kinase activation in rat-2 fibroblasts. Mol Cells 2002; 13: 470–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CR. Commonality within diversity: the plasma membrane transformation of uterine epithelial cells during early placentation. J Assist Reprod Genet 1998; 15: 179–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CR, Shaw TJ. Plasma membrane transformation: a common response of uterine epithelial cells during the peri-implantation period. Cell Biol Int 1994; 18: 1115–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CR. Uterine receptivity and the plasma membrane transformation. Cell Res 2004; 14: 259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thie M, Fuchs P, Denker HW. Epithelial cell polarity and embryo implantation in mammals. Int J Dev Biol 1996; 40: 389–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thie M, Herter P, Pommerenke H, Durr F, Sieckmann F, Nebe B et al. Adhesiveness of the free surface of a human endometrial monolayer for trophoblast as related to actin cytoskeleton. Mol Hum Reprod 1997; 3: 275–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimber SJ, Spanswick C. Blastocyst implantation: the adhesion cascade. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2000; 11: 77–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orchard MD, Murphy CR. Alterations in tight junction molecules of uterine epithelial cells during early pregnancy in the rat. Acta Histochem 2002; 104: 149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson MD, Lindsay LA, Murphy CR. Ovarian hormones control the changing expression of claudins and occludin in rat uterine epithelial cells during early pregnancy. Acta Histochem 2010; 112: 42–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson A, Driessens M, Aspenstrom P. The mammalian homologue of the Caenorhabditis elegans polarity protein PAR-6 is a binding partner for the Rho GTPases Cdc42 and Rac1. J Cell Sci 2000; 113: 3267–3275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens AE, Rygiel TP, Olivo C, van der Kammen R, Collard JG. The Rac activator Tiam1 controls tight junction biogenesis in keratinocytes through binding to and activation of the Par polarity complex. J Cell Biol 2005; 170: 1029–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan O, Ornek T, Fadiel A, Carrick KS, Arici A, Doody K et al. Expression and activation of the membrane-cytoskeleton protein ezrin during the normal endometrial cycle. Fertil Steril 2012; 97: 192–199 e192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faure S, Salazar-Fontana LI, Semichon M, Tybulewicz VL, Bismuth G, Trautmann A et al. ERM proteins regulate cytoskeleton relaxation promoting T cell-APC conjugation. Nat Immunol 2004; 5: 272–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijhara R, van Hennik PB, Gignac ML, Kruhlak MJ, Hordijk PL, Delon J et al. Rac1 mediates collapse of microvilli on chemokine-activated T lymphocytes. J Immunol 2004; 173: 4985–4993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernuda-Morollon E, Millan J, Shipman M, Marelli-Berg FM, Ridley AJ. Rac activation by the T-cell receptor inhibits T cell migration. PLoS One 2010; 5: e12393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao GH, Beeser A, Chernoff J, Testa JR. p21-activated kinase links Rac/Cdc42 signaling to merlin. J Biol Chem 2002; 277: 883–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sells MA, Knaus UG, Bagrodia S, Ambrose DM, Bokoch GM, Chernoff J. Human p21-activated kinase (Pak1) regulates actin organization in mammalian cells. Curr Biol 1997; 7: 202–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epting D, Slanchev K, Boehlke C, Hoff S, Loges NT, Yasunaga T et al. The Rac1 regulator ELMO controls basal body migration and docking in multiciliated cells through interaction with Ezrin. Development 2015; 142: 174–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin S, Ray RM, Johnson LR. Rac1 mediates intestinal epithelial cell apoptosis via JNK. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2006; 291: G1137–G1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu WL, Chen YH, Chao KC, Chang SP, Tsui KH, Li HY et al. Anti-fas activating antibody enhances trophoblast outgrowth on endometrial epithelial cells by induction of P38 MAPK/JNK-mediated apoptosis. Placenta 2008; 29: 338–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li HY, Chang SP, Yuan CC, Chao HT, Ng HT, Sung YJ. Nitric oxide induces extensive apoptosis in endometrial epithelial cells in the presence of progesterone: involvement of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Mol Hum Reprod 2001; 7: 755–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shifrin Y, Pinto VI, Hassanali A, Arora PD, McCulloch CA. Force-induced apoptosis mediated by the Rac/Pak/p38 signalling pathway is regulated by filamin A. Biochem J 2012; 445: 57–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heng S, Cervero A, Simon C, Stephens AN, Li Y, Zhang J et al. Proprotein convertase 5/6 is critical for embryo implantation in women: regulating receptivity by cleaving EBP50, modulating ezrin binding, and membrane-cytoskeletal interactions. Endocrinology 2011; 152: 5041–5052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Kong S, Wang B, Cheng X, Chen Y, Wu W et al. Uterine Rbpj is required for embryonic-uterine orientation and decidual remodeling via Notch pathway-independent and -dependent mechanisms. Cell Res 2014; 24: 925–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Zhang S, Nakano H, Simmons DG, Wang S, Kong S et al. A positive feedback loop involving Gcm1 and Fzd5 directs chorionic branching morphogenesis in the placenta. PLoS Biol 2013; 11: e1001536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Lu J, Zhang S, Wang S, Wang W, Wang B et al. Wnt6 is essential for stromal cell proliferation during decidualization in mice. Biol Reprod 2013; 88: 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.