Abstract

Objectives. To describe trends in benzodiazepine prescriptions and overdose mortality involving benzodiazepines among US adults.

Methods. We examined data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey and multiple-cause-of-death data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Results. Between 1996 and 2013, the percentage of adults filling a benzodiazepine prescription increased from 4.1% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 3.8%, 4.5%) to 5.6% (95% CI = 5.2%, 6.1%), with an annual percent change of 2.5% (95% CI = 2.1%, 3.0%). The quantity of benzodiazepines filled increased from 1.1 (95% CI = 0.9, 1.2) to 3.6 (95% CI = 3.0, 4.2) kilogram lorazepam equivalents per 100 000 adults (annual percent change = 9.0%; 95% CI = 7.6%, 10.3%). The overdose death rate increased from 0.58 (95% CI = 0.55, 0.62) to 3.07 (95% CI = 2.99, 3.14) per 100 000 adults, with a plateau seen after 2010.

Conclusions. Benzodiazepine prescriptions and overdose mortality have increased considerably. Fatal overdoses involving benzodiazepines have plateaued overall; however, no evidence of decreases was found in any group. Interventions to reduce the use of benzodiazepines or improve their safety are needed.

In 2013, an estimated 22 767 people died of an overdose involving prescription drugs in the United States.1 Benzodiazepines, a class of medications with sedative, hypnotic, anxiolytic, and anticonvulsant properties, were involved in approximately 31% of these fatal overdoses.1 In 2008, an estimated 5.2% of American adults filled 1 or more benzodiazepine prescriptions2; however, little is known about national trends over time. We investigated trends in prescriptions of benzodiazepines and fatal overdoses involving benzodiazepines among adults in the United States.

METHODS

We obtained data on filled benzodiazepine prescriptions from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. In each year of the survey, we coded whether each adult respondent (age ≥ 18 years) filled 1 or more benzodiazepine prescriptions. To calculate the total quantity of benzodiazepine prescriptions filled each year, we summed the quantity of each benzodiazepine type and converted to milligram lorazepam equivalents.3

Overdose deaths involving benzodiazepines were extracted from multiple-cause-of-death data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from 1999 to 2013.4 We defined overdose deaths involving benzodiazepines as fatal drug or alcohol poisonings (International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision,5 codes X40–X45, X60–X65, Y10–Y15) when a benzodiazepine was also coded (T42.4). This captures all overdose deaths determined by the physician, medical examiner, or coroner to involve a benzodiazepine, including those involving other medications or illicit drugs.

To describe trends over time, we used the Joinpoint Regression Program (Version 4.2.0.2; Statistical Research and Applications Branch, National Cancer Institute, Rockville, MD). We summarized trends between joinpoints by calculating an annual percent change. We summarized overall trends by calculating the average annual percent change over the entire study period. A full description of the study methods is provided in the Appendix (available as a supplement to the online version of this brief at http://www.ajph.org).

RESULTS

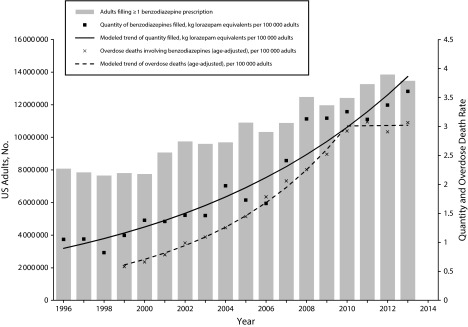

Between 1996 and 2013, the number of adults filling a benzodiazepine prescription increased 67%, from 8.1 million (confidence interval [CI] = 7.3 million, 8.9 million) to 13.5 million (95% CI = 12.2 million, 14.7 million; Figure 1). Similarly, the percentage of adults filling a benzodiazepine prescription increased from 4.1% (95% CI = 3.8%, 4.5%) to 5.6% (95% CI = 5.2%, 6.1%), with an annual percent change of 2.5% (95% CI = 2.1%, 3.0%). The total quantity of benzodiazepines filled more than tripled from 1.1 (95% CI = 0.9, 1.2) to 3.6 (95% CI = 3.0, 4.2) kilogram lorazepam equivalents per 100 000 adults (annual percent change = 9.0%; 95% CI = 7.6%, 10.3%; Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this brief at http://www.ajph.org).

FIGURE 1—

Number of Adults Filling a Benzodiazepine Prescription, Quantity Filled, and Overdose Deaths Involving Benzodiazepines: United States, 1996–2013

Among those filling benzodiazepine prescriptions, the median cumulative quantity filled over the year increased by 140%, from 86.8 (interquartile range = 29.8–282.0) to 208.0 (interquartile range = 56.0–652.9) milligram lorazepam equivalents. In 2013, the most common indications for benzodiazepine prescription were anxiety disorders (56.1% [95% CI = 52.2%, 60.1%]), mood disorders (12.1% [95% CI = 9.0%, 15.2%]), and codes in the unclassified category, which includes codes for insomnia (12.0% [95% CI = 9.4%, 14.6%]). The rate of overdose deaths involving benzodiazepines increased more than 4-fold from 0.58 (95% CI = 0.55, 0.62) to 3.07 (95% CI = 2.99, 3.14) per 100 000 adults; however, this rate appeared to plateau after 2010.

Trends in prescriptions and overdose mortality varied between demographic groups (Appendix, Table A, and Figure A, available as supplements to the online version of this brief at http://www.ajph.org). Despite an overall plateau in the rate of overdose deaths involving benzodiazepines, this rate continued to increase throughout the study period for adults aged 65 or older and for Black and Hispanic participants.

DISCUSSION

Between 1996 and 2013, overdose mortality involving benzodiazepines rose at a faster rate than did the percentage of individuals filling prescriptions and the quantity filled. This could be the result of several factors. First, increases in the total quantity filled reflected both an increase in the number of individuals filling benzodiazepine prescriptions and substantial increases in the amount each individual received. Among people who filled benzodiazepine prescriptions, the median quantity filled over the year more than doubled between 1996 and 2013, suggesting either a higher daily dose or more days of treatment, which potentially increased the risk of fatal overdose.6 Second, people at high risk for fatal overdose may be obtaining diverted benzodiazepines (i.e., not directly from medical providers). The proportion of fatal overdoses involving diverted versus prescribed benzodiazepines is unknown. Finally, increases in alcohol use or combining benzodiazepines with other medications (e.g., opioid analgesics) could increase the risk of fatal overdose and explain this rise. Prescribing of opioid analgesics increased rapidly during most of the period examined,7,8 concomitant benzodiazepine use among those prescribed opioid analgesics is common,8,9 and opioids are involved in an estimated 75% of the overdose deaths involving benzodiazepines.10 The leveling off of overdose mortality involving benzodiazepines was coincident with the time when efforts to improve opioid safety were becoming widespread and overdose deaths involving opioid analgesics stabilized.11

Future research should examine the roles of these potential mechanisms to identify effective policy interventions to improve benzodiazepine safety. In particular, as underscored by several recent reports,6,10,12 interventions to reduce concurrent use of opioid analgesics or alcohol with benzodiazepines are needed.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey was limited to the civilian, noninstitutionalized population, whereas institutionalized patients, such as those in correctional facilities or skilled nursing facilities, are likely to have different rates of benzodiazepine use and overdose. Second, variation in methods used to characterize deaths over time and between states may have led to misclassification. States vary in methods used to characterize deaths, including use of toxicological testing.13 Identification of deaths involving benzodiazepines may have improved over time with widespread adoption of prescription monitoring programs (i.e., state-level registries of controlled substance prescriptions). However, some drug overdose deaths were missing information on specific drugs involved (approximately 22% in 2013).11 Therefore, our findings probably represent underestimates. Third, we could not analyze long-term versus short-term use of benzodiazepines over time because the duration of treatment of prescriptions (i.e., the number of days’ supply) was not recorded for most years of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. A recent study found that the prevalence of long-term use (≥ 120 days) increased with age; among people aged 65 to 80 years taking benzodiazepines, nearly one third (31.4%) had long-term use.2 Fourth, precise estimates of benzodiazepine prescriptions filled among subgroups were limited by sample sizes in the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, which may have limited our ability to detect changes in trends over time. Finally, although the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey included race/ethnicity information for Asian/Pacific Islander and Native American/Alaska Native populations, the sample size was too small to produce reliable estimates.

Public Health Implications

In summary, the number of American adults filling a benzodiazepine prescription is increasing, and the quantity filled is also increasing. Although the rate of overdose deaths involving benzodiazepines has stabilized overall and in most groups, it remains more than 5 times the rate at the start of the study period. Continued increases in overdose deaths involving benzodiazepines among certain groups (e.g., older adults and racial/ethnic minority individuals) are concerning. Furthermore, we found no evidence of reductions in any group. Interventions to reduce the use of benzodiazepines or improve their safety are needed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (C. O. Cunningham: NIH K24DA036955 and R25DA023021; J. L. Starrels: NIH K23DA027719).

Note. The funding bodies had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the brief.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

This study of publicly available deidentified data was not considered human subjects research by the Montefiore Medical Center institutional review board.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prescription drug overdose data. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/overdose.html. April 30, 2015. Accessed September 30, 2015.

- 2.Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M. Benzodiazepine use in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:136–142. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chouinard G, Lefko-Singh K, Teboul E. Metabolism of anxiolytics and hypnotics: benzodiazepines, buspirone, zoplicone, and zolpidem. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1999;19:533–552. doi: 10.1023/A:1006943009192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Vital Statistics System. Multiple Cause of Death 1999-2013. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014. Available at: http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10.html. Accessed September 30, 2015.

- 5.International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park TW, Saitz R, Ganoczy D, Ilgen MA, Bohnert AS. Benzodiazepine prescribing patterns and deaths from drug overdose among US veterans receiving opioid analgesics: case-cohort study. BMJ. 2015;350 doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2698. h2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers—United States, 1999–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(43):1487–1492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larochelle MR, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D, Wharam JF. Trends in opioid prescribing and co-prescribing of sedative hypnotics for acute and chronic musculoskeletal pain: 2001-2010. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;24:885–892. doi: 10.1002/pds.3776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saunders KW, Von KM, Campbell CI et al. Concurrent use of alcohol and sedatives among persons prescribed chronic opioid therapy: prevalence and risk factors. J Pain. 2012;13:266–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones CM, McAninch JK. Emergency department visits and overdose deaths from combined use of opioids and benzodiazepines. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(4):493–501. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hedegaard H, Chen LH, Warner M. Drug-poisoning deaths involving heroin: United States, 2000-2013. NCHS Data Brief. 2015;(190):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones CM, Paulozzi LJ, Mack KA. Alcohol involvement in opioid pain reliever and benzodiazepine drug abuse-related emergency department visits and drug-related deaths - United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:881–885. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warner M, Paulozzi LJ, Nolte KB, Davis GG, Nelson LS. State variation in certifying manner of death and drugs involved in drug intoxication deaths. Acad Forensic Pathol. 2013;3(2):231–237. [Google Scholar]