Abstract

Short-chain acyl-coA dehydrogenase deficiency (SCADD) is an autosomal recessive inborn error of mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation caused by ACADS gene alterations. SCADD is a heterogeneous condition, sometimes considered to be solely a biochemical condition given that it has been associated with variable clinical phenotypes ranging from no symptoms or signs to metabolic decompensation occurring early in life.

A reason for this variability is due to SCAD alterations, such as the common p.Gly209Ser, that confer a disease susceptibility state but require a complex multifactorial/polygenic condition to manifest clinically.

Our study focuses on 12 SCADD patients carrying 11 new ACADS variants, with the purpose of defining genotype–phenotype correlations based on clinical data, metabolite evaluation, molecular analyses, and in silico functional analyses.

Interestingly, we identified a synonymous variant, c.765G > T (p.Gly255Gly) that influences ACADS mRNA splicing accuracy. mRNA characterisation demonstrated that this variant leads to an aberrant splicing product, harbouring a premature stop codon.

Molecular analysis and in silico tools are able to characterise ACADS variants, identifying the severe mutations and consequently indicating which patients could benefit from a long term follow- up. We also emphasise that synonymous mutations can be relevant features and potentially associated with SCADD.

Abbreviations: SCAD, Short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase; SCADD, Short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency; C4-C, butyrylcarnitine; EMA, ethylmalonic acid; NBS, Newborn screening; LC–MS/MS, Tandem mass spectrometry; ACADS, Acyl CoA-deydrogenase, short chain

Keywords: ACADS, SCAD, Short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, Synonymous mutation

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Molecular and functional analysis can identify severe genotypes

-

•

Patients with severe genotype should receive a long term follow-up.

-

•

We identified the first SCAD synonymous variant.

-

•

The first SCAD silent variant was proven to achieve into a disease causing allele.

1. Introduction

Short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (SCAD) deficiency (SCADD, MIM 201470) is an autosomal recessive inborn error of mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation with highly variable clinical, biochemical and genetic characteristics [1]. SCADD is one of the most common inborn errors of metabolism since it is estimated to affect approximately 1 in 35,000 to 50,000 newborns [1], [2].

The characteristic manifestations of SCAD (MIM 606885) deficiency include hypoglycaemia, weakness hypotonia and lethargy [3]

Biochemically, SCADD is associated with the accumulation of butyrylcarnitine (C4-C), butyrylglycine, ethylmalonic acid (EMA), and methylsuccinic acid in blood, urine and cells [4]. Blood C4-C and urinary EMA are generally elevated and thus are currently used as biochemical markers of the disease [1].

SCAD is a flavoprotein consisting of four subunits, each of them containing one molecule of the flavin adenine dinucleotide cofactor (FAD). FAD binding is important for the catalytic activity of flavoproteins, as well as their folding, assembly, and/or stability [5], [6].

Clinically, SCADD is usually diagnosed as a result of investigations for developmental delay, epilepsy, behavioural disorders, hypoglycaemia, and hypotonia.

Newborn screening (NBS) using tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) has led to the identification of an increasing number of newborns with altered biochemical markers suggesting SCADD. However, in contrast to infants in whom clinical manifestations are a cause of referral, infants brought to medical attention by NBS programmes could remain largely asymptomatic [1], [7].

The diagnosis of SCADD is usually confirmed by molecular analysis. The ACADS gene (MIM #606885), encoding SCAD, spans approximately 14.2 kb and consists of ten exons. To date, more than 60 inactivating mutations have been reported in the ACADS gene, two of which, the c.511C > T (p.Arg171Trp) and c.625G > A (p.Gly209Ser), are polymorphic and generally referred to as gene variants. These two variants have not been directly associated with SCADD although they were reported to confer disease susceptibility when co-occurring with as yet undetermined environmental or genetic factors [8], [9]. Assuming that these ACADS variants result in protein misfolding [10], riboflavin (the precursor of FAD) therapy might be efficacious. However, riboflavin responsiveness in individuals with the c.625G > A (p.Gly209Ser) variant at a homozygous state, was detected only in combination with an initial low FAD status observed in patients' blood samples [11].

The purpose of this study is to increase the knowledge on the clinical relevance of SCADD. We focus on 12 cases of SCADD exhibiting a new genotype and report their clinical, biochemical and molecular data. We detected 11 new mutations in the ACADS gene including the first synonymous (silent) mutation in a SCADD disease causing allele. We evaluated the pathogenic role of the new missense variants identified using in silico predictions and performed RT-PCR analysis to study the effects of the synonymous variant.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Clinical and biochemical analysis

This study was carried out on 12 patients from 11 unrelated families.

Clinical features, the EMA and C4-C values and ACADS gene molecular analyses are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Genotype, biochemical values and clinical features of the here reported 12 SCADD patients.

| Patient | ACADS gene Allele 1 | ACADS gene Allele 2 | Age at diagnosis | Ethnic origin | C4-C μmol/L (DBS) (n.v < 1) | EMA mmol/mol creatinine (n.v. < 7) | Clinical symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

c. 842G > C p.Gly281Ala c.625G > A p.Gly209Ser |

c.625G > A p.Gly209Ser | 5 y | Italian | – | 48 | Hypotonia, developmental delay, epilepsy, dysmorphic features, microcephaly and maculopathy |

| 2 | c.869C > G p.Ala290Gly c.625G > A p.Gly209Ser | c.625G > A p.Gly209Ser | 26 d | Italian | n.a | 42 | None |

| 3 | c.981_983delGAC | c.322G > A p.Gly108Ser | 15 d | Philippine | 1.05 | 154 | Mild hypotonia, mild hypertransaminasaemia |

| 4 | c.1054G > A p.Ala352Thr c.625G > A p.Gly209Ser | c.1054G > A p.Ala352Thr c.625G > A p.Gly209Ser | 9 d | Moroccan | 4 | 182 | none |

| 5 | c.1130C > T p.Pro377Leu | c.625G > A p.Gly209Ser | 17 y | Italian | – | 14 | Pervasive developmental disorder, stereotypies, dysmorphic features |

| 6 | c.700C > T p.Arg234Trp | c.625G > A p.Gly209Ser | 9 d | Moroccan | 1.59 | 33 | None |

| 7 | c.1157G > A p.Arg386His c.625G > A p.Gly209Ser | c.625G > A p.Gly209Ser | 8 d | Romanian | 1 | 28 | None |

| 8 | c.814C > T p.Arg272Cys | c.814C > T p.Arg272Cys | 16 d | Moroccan | 1.87 | 187 | Mild hypotonia |

| 9 | c.814C > T p.Arg272Cys | c.814C > T p.Arg272Cys | 8 d | Moroccan | 1.80 | 96 | Mild hypotonia |

| 10 | c.66G > A p.W22* | c.625G > A p.Gly209Ser | 8 d | Pakistani | 1.13 | 36 | None |

| 11 | c.700C > T p.Arg234Trp | c.700C > T p.Arg234Trp | 14 d | Italian | 2.25 | 220 | Mild hypotonia |

| 12 | c.531 G > A p.Trp171* | c.765G > T p.Gly255Gly | 9 d | Italian | 1.98 | 129 | None |

– not performed: they were born before NBS programmes were established in our country; n.a. not available; y = years; d = days; n.v = normal values. The new variants are bolded. Patients 8 and 9 are brothers.

According to ethical guidelines, all cell and nucleic acid samples were obtained for analysis and storage after patients' (and/or parental) written informed consent, using a form approved by the local Ethics Committee.

Quantitative assay of acylcarnitine was performed by tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) using an ABiSciex API 4000 triple-quadruple mass spectrometer equipped with a TurboIonSpray source (ABiSciex, Toronto, Canada) as previously reported [12].

2.2. Analysis of genomic DNA

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood lymphocytes or cultured fibroblasts, or both.

Amplification of genomic fragments was performed on 200 ng of genomic DNA; PCR conditions for all the ACADS exons included denaturation at 94 °C for 4 min, 30 cycles at 94 °C for 30 s, 63 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 2 min, and a final extension cycle at 72 °C for 10 min.

PCR products were visualised on a 2% agarose gel and purified using Nucleospin Extract II extraction kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). About 100 ng of purified DNA was analysed for mutation detection by nucleotide sequencing on an ABI PRISM 3130 genetic analyser using BigDye terminator chemicals (Life Technologies Italia, Monza, Italy).

2.3. Cell culture

T lymphocytes were cultured in RPMI medium added by foetal bovine serum (heat inactivated for 30 min at 56 °C), interleukin 2 (800 μ/ml), phytohemagglutinin (2.5 μg/ml) and antibiotics.

2.4. mRNA analyses

Total RNA was isolated from T lymphocytes cells by using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). RNA integrity and concentration were checked by 1% agarose gel and Nanodrop® ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (Nanodrop technologies, Wilmington, USA).

Total RNA (200 ng) was reverse transcribed with random hexamers by using TaqMan Reverse Transcriptase kit (Applied Biosystems by Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RT-PCR analysis was performed using 2 μl of retrotranscribed products as template and primers RNA3F (5′-GTCATCATGAGTGTCAACAAC-3′) and RNA8R (3′-CTTGATGAAAGGCTTCTTGTTA-5′) that anneal the ACADS exons 3 and 8, respectively. PCR reactions were prepared in 25 μl of final volume in a reaction mixture containing 1 × PCR buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 250 μM each dNTP, 15 pmol of each primer, and 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems by Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). After a primary denaturation for 5 min at 95 °C, amplification was carried out for 30 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 56 °C and 2 min at 72 °C, with a final extension of 7 min at 72 °C.

Splicing predictions performed by Alamut® software (http://www.interactive-biosoftware.com/alamut.html), based on 5 different algorithms (SpliceSiteFinder, MaxEntScan, NNSPLICE, GeneSplicer, Human Splicing Finder), were used to assume the role of the c.765G > T genetic variation on the ACADS translation.

2.5. Screening of new mutations and in silico analyses

The 1000 Genomes project database (http://www.1000genomes.org/), including all human genetic variations from the dbSNP short genetic variations database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim) and the ExAC Browser of the Exome Aggregation Consortium, which provides a data set spanning over 60,000 unrelated individuals (http://exac.broadinstitute.org), were used to evaluate the polymorphic status of the identified genetic alterations. The frequency of the newly identified missense variants in the Italian population was also evaluated by sequencing the ACADS gene in 100 healthy controls DNAs.

2.6. In silico analysis and tridimensional modelling of new missense mutations onto the SCAD protein

The 3D SCAD structure and chemical bonds were examined in UCSF Chimera (http://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera/)(version 1.6.1) [13].

We used different mutation characterisation methods to analyse the effect of the 7 ACADS alterations identified, including PolyPhen-2 [14], Meta-SNP (including results from other tools: PANTHER, PhD-SNP, SIFT, and SNAP) [15], PON-P2 [16], PredictSNP (also including results from MAPP, PhD-SNP, PolyPhen-1, PolyPhen-2, SIFT, SNAP, nsSNPAnalyzer, and PANTHER) [17], MutPred [18] and MutPred2. The latter is the latest version of MutPred, which is a joint project of Dr. Sean Mooney's laboratory at the University of Washington and Dr. Predrag Radivojac's laboratory at Indiana University and is available upon request.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical and biochemical data

We report the available clinical and biochemical information collected for each patient from the referring physicians (Table 1). Biochemically, we report the data on the C4-C measurements on DBS and the subsequent EMA values, established before the beginning of the riboflavin therapy. The available C4-C retesting confirmed the data of the first assessments (data not shown).

The age of patients at the time of the study ranged from newborn to 24 years. All patients were born from unrelated parents with the exception of Pt 4, Pt 8, Pt 9, and Pt 11, who were born from consanguineous parents.

10 SCADD patients were enrolled through NBS programmes and their diagnosis was confirmed between 7 and 26 days of age upon detecting elevated plasma C4-c and increased excretion of urinary EMA (Table 1). None of these patients were found to be carnitine deficient and the genetic and biochemical metabolic work-up pointed to the possibility of SCADD. At present, these patients are undergoing riboflavin therapy and they are all still asymptomatic.

However, hypotonia was observed at the moment of recall for C4 positive screening between 8 and 16 days of life in Pts, 8, 9 and 11. Pregnancy or neonatal complications in these patients were excluded. The hypotonia improved and completely disappeared after riboflavin treatment was established. At present, after an 8 year long follow-up, patients are asymptomatic. Riboflavin treatment has maintained patients' EMA urinary levels at significantly lower values.

Pts 1 and 5 were brought to medical attention, at 5 and 17 years of age, due to developmental delay and dysmorphic features. Epilepsy, microcephaly and maculopathy were also observed in Pt 1. All patients diagnosed through NBS began riboflavin therapy within 20 days to 2 months of age. Pt 1 is also being treated with antiepileptic drugs.

3.2. ACADS molecular analysis

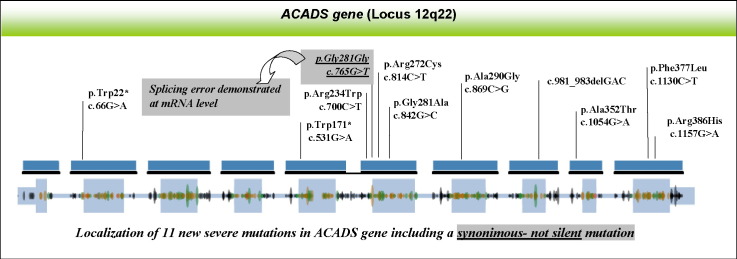

Of the 13 different genetic alterations identified, 11 were novel, 7 missense: [c.700C > T (p.Arg234Trp), c.814C > T (p.Arg272Cys), c.842G > C (p.Gly281Ala), c.869C > G (p.Ala290Gly), c.1054G > A (p.Ala352Thr), c.1130C > T (p.Pro377Leu), c.1157G > A (p.Arg385His)], 2 nonsense: c.66G > A (p.W22*) and c.531G > A (p.Trp171*), 1 deletion (c.981_983delGAC) and 1 synonymous [c.765G > T (p.Gly255Gly)].

Among the 7 new missense variants, 5 occurred at new positions (p.Arg234, p.Gly281, p.Ala290, p.Ala352 and p.Pro377); the remaining two amino acids (p.Arg272 and p.Arg386) had previously been found to generate other disease-causing alleles [1]. The homozygous or heterozygous state of the ACADS genetic variants was confirmed by molecular analysis in all patients' relatives.

3.3. In silico structural predictions of new ACADS missense variants

None of the missense variants (p.Arg234Trp, p.Arg272Cys, p.Gly281Ala, p.Ala290Gly, p.Ala352Thr, p.Pro377Leu and p.Arg386His) or the synonymous variant (c.765G > T) were found in the Italian control population. The 1000 Genomes project database does not include the newly presented variants except for the p.Pro377Leu (MAF = 0.0002). In the EXAC browser all the new variants identified were present at very low frequency (MAF ranging from 0.0008 to 0.002).

We used different mutation characterisation methods to analyse the possible association of the 7 genetic alterations here reported with SCADD.

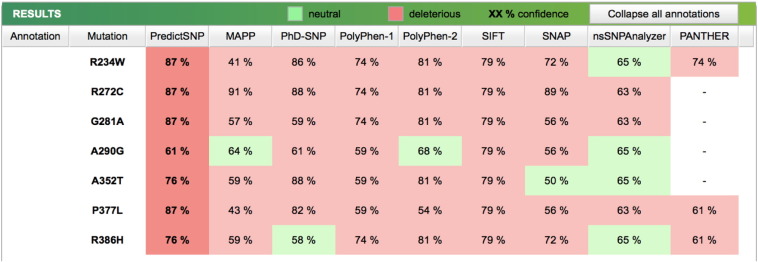

Most of the tools (e.g., PANTHER, PhD-SNP, SIFT, SNAP, PredictSNP, PolyPhen-1, PolyPhen-2, MutPred, MutPred2) predict that the 7 mutations are probably disease causing (Fig. 1). A graphical view of the altered amino acids mapped onto the tridimensional SCAD structure is reported in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1.

Results of the predicted effect of the missense mutations identified using the PredictSNP tools MAPP, PhD-SNP, PolyPhen-1, PolyPhen-2, SIFT, SNAP, nsSNPAnalyzer, and PANTHER.

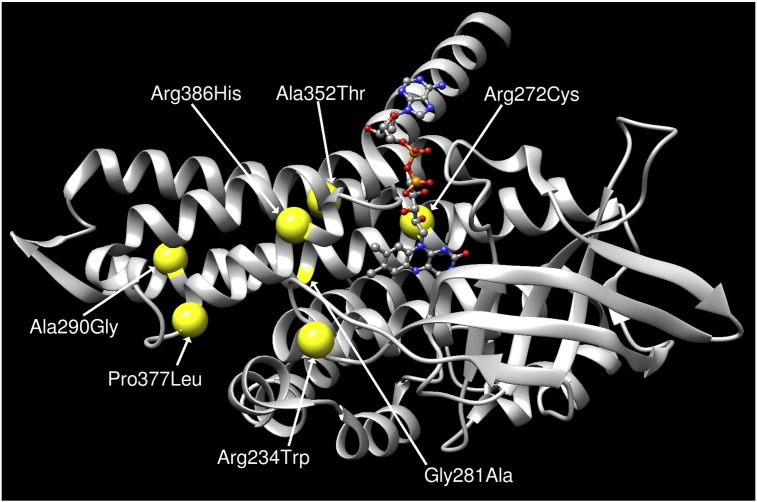

Fig. 2.

SCAD protein: tridimensional structure predictions highlighting positions of the new missense mutations identified. The graph is generated via UCSF Chimera package (http://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera/).

Structural and functional properties of protein sequences were analysed by MutPred to predict the actionable molecular mechanism of disruption due to these amino acid variants on SCAD. These results suggest that the p.Arg272Cys is very likely to cause loss of a methylation function, and p.Arg386His is likely to cause loss of protein stability. Both cases are considered to be disruptive with a confident score. The MutPred results also gave actionable hypotheses of disruptions for all the 7 mutations, including loss of intrinsic disorder due to p.Arg234Trp, loss of protein stability due to p.Ala290Gly, and gain of protein stability and loss of intrinsic disorder because of p.Pro377Leu (Fig. 2, Table 2).

Table 2.

SCAD missense mutations analysis with prediction software tools.

| Variant | MutPred Probability of deleterious mutation |

MutPred2 Probability of deleterious mutation |

Molecular mechanism disrupted hypotheses (P⁎< 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|

| c.700C > T (p.Arg234Trp) | 0.581 | 0.838 | Loss of disorder |

| c.814C > T (p.Arg272Cys) | 0.966 | 0.917 | Loss of methylation at Arg272 Gain of palmitoylation at R272 |

| c.842G > C (p.Gly281Ala) | 0.979 | 0.938 | – |

| c.869C > G (p.Ala290Gly) | 0.761 | 0.763 | Loss of stability |

| c.1054G > A (p.Ala352Thr) | 0.788 | 0.876 | – |

| c.1130C > T (p.Pro377Leu) | 0.754 | 0.836 | Gain of stability Loss of disorder |

| c.1157G > A (p.Arg386His) | 0.905 | 0.917 | Loss of stability |

P is the P-value that certain structural and functional properties are impacted.

The results obtained from MutPred2, that considers around 57 structural/functional properties compared to the 14 properties used by MutPred, indicate that all 7 variants are probably deleterious with scores above 0.75. The results also show a very confident hypothesis that the SCAD protein is very likely to gain a palmitoylation function if the arginine at position p.272 of SCAD is mutated to cysteine.

Overall, the results from the different mutation prediction tools suggest that these 7 mutations are likely to be deleterious.

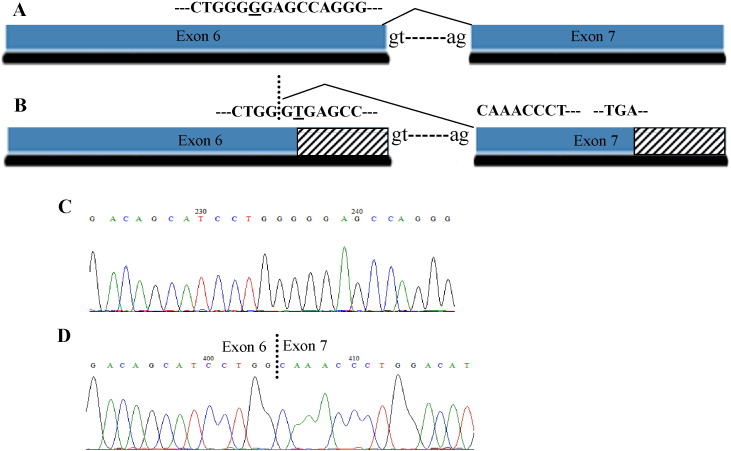

3.4. Characterisation of ACADS m-RNA product resulting from the c.765G > T (p.Gly255Gly) new synonymous variant

In silico algorithms predicted that the exonic c.765G > T (p.Gly255Gly) variant would create a new cryptic donor splice site (Fig. 3). This genetic lesion was identified at the heterozygous state in Pt 12 and in his father. Pt 2 and his relatives were analysed by RT-PCR using an oligonucleotide set designed to discriminate between the wt ACADS transcript and the aberrant transcript potentially induced by the silent variant. This analysis produces a 519 bp amplicon corresponding to the wild-type ACADS mRNA in the patient's sample, in his relatives and in controls, and a 487 bp amplicon, corresponding to an alternative transcript, detected in the patient's and in his father's samples (Fig. 3). Sequencing analysis of the amplified fragments from the patient's sample reveals the c.765G > T variant in the shorter amplicon and the second disease causing mutation [c.66G > A (p.W22*)] in the longer fragment, both at the homozygous state. Detection of both these mRNAs in this sample ruled out nonsense mediated decay (NMD) pathways, which could be determined by both variants. The alternative m-RNA resulted in an aberrant frame shift ending in a premature stop codon (PTC), at position c.882 of the ACADS cDNA. This mutation can be defined as p.Gly255Alafs*30 at the protein level.

Fig. 3.

Splicing alteration caused by the c.765G > T variant detected in Pt 12 at a heterozygous state.

A. Correct splicing event. The wild type nucleotide that is changed in the aberrant m-RNA product is underlined. B. Aberrant splicing event, consisting of a 31 nucleotide deletion in exon 6, due to an additional donor site. Dotted lines indicate a different coding frame occurring in the aberrant splicing product. The nucleotide change is underlined. C. Normal sequence analysis of exon 6 from m-RNA analysis performed in normal controls D. Aberrant splicing from Pt12 m-RNA analysis.

4. Discussion

The clinical spectrum of SCAD deficiency is extremely heterogeneous [1], [9]. Available clinical, biochemical, and molecular data from our series were analysed for determining whether the genotype had a substantial role in developing signs and symptoms.

We highlight two main consequences. First, there were clinical differences between children identified by NBS compared to those identified clinically. The latter exhibited severe clinical symptoms including developmental delay, dysmorphic features and epilepsy. This finding is in keeping with previously reported comparative studies including patients identified by NBS and clinically referred patients [19].

All patients in our study exhibited at least one new mutation in the ACADS gene. We underline that EMA and C4-C levels are altered in all the here reported patients' samples, both patients with two new mutations (Mut/Mut patients) and patients compound heterozygous for a new mutation and the common c.625G > A variant (Mut/Var patients), as also previously reported [1].

Our results indicate that initial C4-C levels cannot differentiate between Mut/Mut and Mut/Var patients. A correlation between C4-C levels and genotypes was not found, probably because acylcarnitine amounts may be sensitive to how long a patient has fasted [9].

Conversely, differences occurred in patients' urinary EMA levels depending on genotype. The Mut/Mut patients showed EMA levels far above 100 mmol/mol creatinine, whereas patients compound heterozygous for a new mutation and the common c.625G > A variant (Mut/Var patients) presented EMA levels below 100 mmol/mol creatinine.

Molecular analyses were performed to define eventual genotype–phenotype correlations in our cohort. Only 59 ACADS mutations are reported to cause SCADD (https://portal.biobase-international.com/hgmd/), even if the disease has an incidence of 1:35.000–50.000 live births, and the gene is composed by 10 exons spanning about 14.2 kb, in keeping with the average length of human genes. We here report 11 new variants, a consistent number of mutations identified in the ACADS gene at the present time. Between these variants, three are drastic changes, two nonsense mutations and one deletion, which clearly give rise to deleterious effects on the corresponding SCAD proteins.

In silico tools were used to evaluate the potential pathogenic role of the newly identified missense variants. Computational analyses suggest that the 7 new missense mutations we identified cause abnormal protein structures and functions of the SCAD enzyme, thereby leading to disease. In particular, there is a very confident hypothesis that the p.Arg272Cys causes the gain of palmitoylation in this position. S-Palmitoylation is a key regulatory mechanism controlling protein targeting, localisation, stability, and activity and that the potential loss or gain of palmitoylation sites are closely associated with human disease [20].

Various studies have addressed the possibility that SCADD could be monogenic, multifactorial or a benign condition [8], [9], [10], [19], [21]. In particular, it is doubtful if SCADD is suited for inclusion in NBS programmes [22].

Based on our data it emerges a second main consequence: functional/structural data can elucidate the role of new missense variants identified in SCADD patients. Molecular data clearly correlate with biochemical levels of SCADD metabolic biomarkers. Perspective studies with long term follow-up are needed to carefully monitor the eventual onset of neurological manifestations in patients detected by NBS programmes, as previously demonstrated [2]. We emphasise that molecular analysis, which can identify severe genotypes, can indicate which patients should unquestionably receive a long term follow-up.

Furthermore, we identified the first synonymous and pathogenic substitution in the SCAD protein. Nucleotide substitutions in gene coding regions, which do not alter protein sequence, were traditionally hypothesised to bear no effect on proteins and were called silent, a concept that has been overturned in recent years [23]. Synonymous mutations are now widely acknowledged to cause disease in humans and to have the potential to influence multiple levels of cellular biology [24]. Indeed, the novel c.765G > T (p.Gly255Gly) synonymous variant generates a splice junction internal to ACADS exon 6, a drastic change resulting in a premature stop codon at SCAD level.

5. Conclusions

In the current era of genome wide association and next generation sequencing projects, our results satisfy the necessity of combining sequencing analysis with functional–structural predictions to derive the clinical significance of the genetic variants identified.

We underline that molecular analysis, which also evaluates the role of uncommon and often uncharacterised variants, along with in silico functional studies, provides physicians with essential information to manage patients diagnosed with SCADD.

Transparency document

Transparency document

Acknowledgments

The partial financial support of the AMMeC (Associazione Malattie Metaboliche e Congenite, Italia) grant number 1/14-15 and the Fondazione Meyer ONLUS, Firenze, is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

The Transparency document associated with this article can be found, in the online version.

References

- 1.van Maldegem B.T., Duran M., Wanders R.J., Niezen-Koning K.E., Hogeveen M., Ijlst L., Waterham H.R., Wijburg F.A. Clinical, biochemical, and genetic heterogeneity in short-chain acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase deficiency. JAMA. 2006;296:943–952. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.8.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallant N.M., Leydiker K., Tang H., Feuchtbaum L., Lorey F., Puckett R., Deignan J.L., Neidich J., Dorrani N., Chang E., Barshop B.A., Cederbaum S.D., Abdenur J.E., Wang R.Y. Biochemical, molecular, and clinical characteristics of children with short chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency detected by newborn screening in California. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2012;106:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corydon M.J., Andresen B.S., Bross P., Kjeldsen M., Andreasen P.H., Eiberg H., Kolvraa S., Gregersen N. Structural organization of the human short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase gene. Mamm. Genome. 1997;8:922–926. doi: 10.1007/s003359900612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corydon M.J., Gregersen N., Lehnert W., Ribes A., Rinaldo P., Kmoch S., Christensen E., Kristensen T.J., Andresen B.S., Bross P., Winter V., Martinez G., Neve S., Jensen T.G., Bolund L., Kolvraa S. Ethylmalonic aciduria is associated with an amino acid variant of short chain acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase. Pediatr. Res. 1996;39:1059–1066. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199606000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henriques B.J., Rodrigues J.V., Olsen R.K., Bross P., Gomes C.M. Role of flavinylation in a mild variant of multiple acyl-CoA dehydrogenation deficiency: a molecular rationale for the effects of riboflavin supplementation. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:4222–4229. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805719200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagao M., Tanaka K. FAD-dependent regulation of transcription, translation, post-translational processing, and post-processing stability of various mitochondrial acyl-CoA dehydrogenases and of electron transfer flavoprotein and the site of holoenzyme formation. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:17925–17932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marsden D., Larson C., Levy H.L. Newborn screening for metabolic disorder. J. Pediatr. 2006;148:S2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gregersen N., Winter V.S., Corydon M.J., Corydon T.J., Rinaldo P., Ribes A., Martinez G., Bennett M.J., Vianey-Saban C., Bhala A., Hale D.E., Lehnert W., Kmoch S., Roig M., Riudor E., Eiberg H., Andresen B.S., Bross P., Bolund L.A., Kolvraa S. Identification of four new mutations in the short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (SCAD) gene in two patients: one of the variant alleles, 511C–> T, is present at an unexpectedly high frequency in the general population, as was the case for 625G–>A, together conferring susceptibility to ethylmalonic aciduria. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1998;7:619–627. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.4.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waisbren S.E., Levy H.L., Noble M., Matern D., Gregersen N., Pasley K., Marsden D. Short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (SCAD) deficiency: an examination of the medical and neurodevelopmental characteristics of 14 cases identified through newborn screening or clinical symptoms. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2008;95:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pedersen C.B., Kolvraa S., Kolvraa A., Stenbroen V., Kjeldsen M., Ensenauer R., Tein I., Matern D., Rinaldo P., Vianey-Saban C., Ribes A., Lehnert W., Christensen E., Corydon T.J., Andresen B.S., Vang S., Bolund L., Vockley J., Bross P., Gregersen N. The ACADS gene variation spectrum in 114 patients with short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (SCAD) deficiency is dominated by missense variations leading to protein misfolding at the cellular level. Hum. Genet. 2008;124:43–56. doi: 10.1007/s00439-008-0521-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Maldegem B.T., Duran M., Wanders R.J., Waterham H.R., Wijburg F.A. Flavin adenine dinucleotide status and the effects of high-dose riboflavin treatment in short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. Pediatr. Res. 2010;67:304–308. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181cbd57b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.la Marca G., Malvagia S., Casetta B., Pasquini E., Donati M.A., Zammarchi E. Progress in expanded newborn screening for metabolic conditions by LC–MS/MS in Tuscany: update on methods to reduce false tests. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2008;31(Suppl. 2):S395–S404. doi: 10.1007/s10545-008-0965-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pettersen E.F., Goddard T.D., Huang C.C., Couch G.S., Greenblatt D.M., Meng E.C., Ferrin T.E. UCSF chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adzhubei I.A., Schmidt S., Peshkin L., Ramensky V.E., Gerasimova A., Bork P., Kondrashov A.S., Sunyaev S.R. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Capriotti E., Altman R.B., Bromberg Y. Collective judgment predicts disease-associated single nucleotide variants. BMC Genomics. 2013;14 Suppl 3:S2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-S3-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niroula A., Urolagin S., Vihinen M. PON-P2: prediction method for fast and reliable identification of harmful variants. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bendl J., Stourac J., Salanda O., Pavelka A., Wieben E.D., Zendulka J., Brezovsky J., Damborsky J. PredictSNP: robust and accurate consensus classifier for prediction of disease-related mutations. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li B., Krishnan V.G., Mort M.E., Xin F., Kamati K.K., Cooper D.N., Mooney S.D., Radivojac P. Automated inference of molecular mechanisms of disease from amino acid substitutions. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2744–2750. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Maldegem B.T., Wanders R.J., Wijburg F.A. Clinical aspects of short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2010;33:507–511. doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9080-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li S., Li J., Ning L., Wang S., Niu Y., Jin N., Yao X., Liu H., Xi L. In silico identification of protein S-palmitoylation sites and their involvement in human inherited disease. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015;55:2015–2025. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.5b00276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Maldegem B.T., Kloosterman S.F., Janssen W.J., Augustijn P.B., van der Lee J.H., Ijlst L., Waterham H.R., Duran R., Wanders R.J., Wijburg F.A. High prevalence of short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency in the Netherlands, but no association with epilepsy of unknown origin in childhood. Neuropediatrics. 2011;42:13–17. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1275342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Maldegem B.T., Duran M., Wanders R.J., Niezen-Koning K.E., Hogeveen M., Ijlst L., Waterham H.R., Wijburg F.A. Short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (SCADD): relatively high prevalence in the Netherlands and strongly variable fenotype; neonatal screening not indicated. Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd. 2008;152:1678–1685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hunt R.C., Simhadri V.L., Iandoli M., Sauna Z.E., Kimchi-Sarfaty C. Exposing synonymous mutations. Trends Genet. 2014;30:308–321. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sauna Z.E., Kimchi-Sarfaty C. Understanding the contribution of synonymous mutations to human disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011;12:683–691. doi: 10.1038/nrg3051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Transparency document