Abstract

Bioenergetics and bioenergetic-related functions are altered in Alzheimer's disease (AD) subjects. These alterations represent therapeutic targets and provide an underlying rationale for modifying brain bioenergetics in AD-affected persons. Preclinical studies in cultured cells and mice found that administering oxaloacetate (OAA), a Krebs cycle and gluconeogenesis intermediate, enhanced bioenergetic fluxes and upregulated some brain bioenergetic infrastructure-related parameters. We therefore conducted a study to provide initial data on the tolerability and pharmacokinetics of OAA in AD subjects. Six AD subjects received OAA 100 mg capsules twice a day for one month. The intervention was well-tolerated. Blood level measurements following ingestion of a 100 mg OAA capsule showed modest increases in OAA concentrations, but pharmacokinetic analyses were complicated by relatively high amounts of endogenous OAA. We conclude that OAA 100 mg capsules twice per day for one month are safe in AD subjects but do not result in a consistent and clear increase in the OAA blood level, thus necessitating future clinical studies to evaluate higher doses.

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; ADASCog, Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive subset; AUC, area under the curve; CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating; CBC, complete blood count; COX, cytochrome oxidase; FDG PET, fluoro-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance; IP, intraperitoneal; KU ADC, University of Kansas Alzheimer's Disease Center; LC–MS/MS, liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry; LFT, liver function tests; MMSE, mini-mental state exam; mtDNA, mitochondrial DNA; OAA, oxaloacetate; PGC1α, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator; PK, pharmacokinetic

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, Clinical trial, Mitochondria, Oxaloacetate, Pharmacokinetics

Highlights

-

•

Oxaloacetate 100 mg twice per day is safe and well tolerated in persons with Alzheimer's disease.

-

•

Oxaloacetate 100 mg twice per day produces at most a limited increase in the blood level.

-

•

Future studies evaluating oxaloacetate's AD treatment potential should evaluate higher doses.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is clinically characterized by cognitive decline [1]. While hypotheses postulate its potential causes and propose various therapeutic targets, no clearly effective disease-modifying interventions are currently recognized.

The single greatest AD risk factor is advancing age. Brain bioenergetic function and mitochondrial integrity decline with advancing age and to a further extent when AD is present [2]. Energy metabolism-associated changes in AD include decreased glucose utilization, as indicated by fluoro-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET) studies that reliably reveal early and neuroanatomically predictable hypometabolic brain regions [3], [4], [5]. Activities of several mitochondria-localized enzymes, including enzymes of the Krebs cycle and the respiratory chain, are also reduced in AD subject brains and in some cases even peripheral tissues [2]. Some brain regions show an overall reduction in the number of normal-appearing mitochondria, apparently increased mitochondrial debris in autophagosomes, and low levels of the mitochondrial biogenesis-promoting peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator (PGC1α) protein [6], [7]. Some AD investigators believe energy metabolism functional and structural changes may contribute to the progression of disease and perhaps even initiate it, and constitute reasonable therapeutic targets [8], [9].

We previously reported changes in bioenergetic fluxes and infrastructure when cells or animals are exposed to various energy metabolism pathway intermediates. One intermediate we evaluated is oxaloacetate (OAA), a dicarboxylic acid found in Krebs cycle and gluconeogenesis fluxes. Administering OAA to cultured neuronal SH-SY5Y cells enhances glycolysis and respiratory fluxes, increases PGC1α mRNA and protein, and increases mRNA and protein levels of a mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)-encoded cytochrome oxidase (COX) subunit [10]. The brains of mice that received a two-week course of intraperitoneal (IP) OAA showed increased levels of PGC1α mRNA, an increase in the nuclear to cytosolic PGC1α protein ratio, and higher amounts of the COX subunit 4 protein [11]. Compared to saline injected mice, the brains of the OAA-treated mice also showed higher hippocampal neurogenesis activity and changes suggesting enhanced brain insulin signaling and reduced neuroinflammation [11]. For these reasons we want to determine the effects of OAA on persons with AD.

2. Methods

This study was approved by the Kansas University Medical Center Human Subjects Committee and informed consent was obtained for all subjects. We recruited six AD subjects from the University of Kansas Alzheimer's Disease Center (KU ADC) Clinical Core cohort; APOE genotype status and clinical dementia rating scale (CDR) scores are independently acquired for KU ADC cohort members. Subjects met the McKhann et al. AD criteria [12], had CDR scores of 0.5 or 1, and had mini-mental state exam (MMSE) scores between 15 and 28. Subjects with a syndromic diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment (as opposed to a full AD diagnosis), as well as subjects with diabetes, were excluded. Each subject had a study partner who was already engaged in their daily social and medical care.

OAA capsules were obtained from Terra Biological LLC (San Diego, California). Terra Biological LLC markets OAA capsules produced using good manufacturing practice procedures, and OAA batches used to prepare these capsules are tested to ensure the integrity of the OAA. The capsules contained 100 mg OAA and 150 mg of ascorbic acid. Because 100 mg of OAA was the lowest amount that could be administered at a given time, we predicted OAA would elevate the blood level for a limited period, and safety was a major focus of this study OAA dosing was set at 100 mg twice per day.

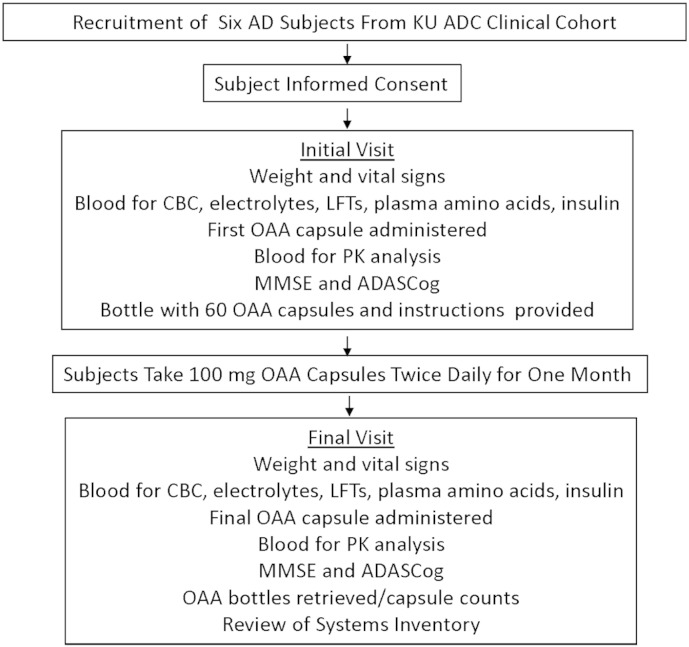

Participation in the study required two study visits, an initial visit and a final study visit 4 weeks later (Fig. 1). For both visits a 36 item review of symptoms inventory was also completed by the subject and the study partner. During the initial visit the first 100 mg OAA capsule was administered and subject assessments were performed. At the conclusion of the initial visit a bottle containing 60 OAA capsules was provided with instructions for the subject to take one capsule each morning and one capsule each evening. Approximately one month later the final study visit was conducted, at which time subjects were assessed at the time of taking their final 100 mg OAA capsule. The OAA bottles were collected and any remaining capsules were counted to assess compliance.

Fig. 1.

Pharmacokinetics of Oxaloacetate (POX) study organization.

For each visit subjects presented at 8 AM to the Clinical Trials Unit of the Kansas University Medical Center having fasted since midnight. The subjects were weighed and vital signs determined. A heparin lock was inserted, and blood was obtained to determine the subject's complete blood count (CBC), electrolytes, liver function tests (LFTs), plasma amino acids, and insulin level. A 3–5 ml baseline blood sample for pharmacokinetic (PK) testing was then obtained, and a 100 mg OAA capsule was orally administered with 200 ml of water. Additional 3–5 ml PK blood samples were obtained at 30, 45, 60, 75, 90, 105, 120, 135, 150, and 240 min after dosing. The PK blood samples were immediately placed on ice and processed into plasma within 10 min of acquisition. Aliquots of plasma (0.5 ml each) were frozen immediately and stored at − 80 °C until analysis. During the time lag between the 150 and 240 min PK phlebotomies, a psychometrician administered an MMSE and Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive subscale (ADASCog) test to each subject. The ADASCog version in our study is the version used by the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study Group, which scores 11 items. Higher scores indicate worse performance and the highest maximum possible score is 70 points.

Quantitation of OAA in plasma was performed using 3 different approaches. We used a commercially available coupled enzyme method assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) that utilizes a fluorescence detection protocol to measure OAA concentrations. This kit also provides an absorption-based protocol for OAA measurements, and the absorption-based approach was used as well. Finally, because OAA undergoes some degree of decarboxylation to pyruvate when it is placed in solution, we adapted and applied a liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS)-based assay for OAA quantitation and to measure plasma pyruvate concentrations [13].

The glucose and insulin levels from each visit were used to calculate the homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) values for each subject using the following equation: (glucose in mg/dl x insulin in mcu/ml)/405. Initial and final visit HOMA-IR, weight, plasma amino acid, and cognitive score values were compared using a paired t-test approach. CBC, electrolyte, and LFT studies were analyzed for the appearance of clinical abnormalities.

3. Results

Subject characteristics are shown in Table 1. Mean age (with standard deviation) was 76.2 ± 8.2. Only one subject lacked an APOE4 allele. All of the subjects completed the study. During the course of the study no adverse events, treatment-induced symptoms, or clinically significant changes in safety labs were observed. Compliance estimates for the six subjects ranged from 76 to 100% (Table 2).

Table 1.

Subject characteristics.

| Subject | Age | Sex | APOE | CDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 64 | M | 4/4 | 0.5 |

| 2 | 68 | M | 3/4 | 1 |

| 3 | 78 | M | 3/3 | 1 |

| 4 | 83 | F | 3/4 | 0.5 |

| 5 | 82 | F | 3/4 | 1 |

| 6 | 82 | M | 3/4 | 1 |

Table 2.

Compliance and safety.

| Subject | Compliance | New symptoms | Clinically significant abnormal safety labs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 89% | None reported | None |

| 2 | 98% | None reported | None |

| 3 | 100% | None reported | None |

| 4 | 82% | None reported | None |

| 5 | 76% | None reported | None |

| 6 | 98% | None reported | None |

Weight, fasting glucose, fasting insulin, and HOMA-IR values for subjects varied between visits, but as a group no consistent changes in weight or HOMA-IR were observed during the course of the study (Table 3). Although there was not a statistically significant reduction in post-treatment fasting glucose levels, post-treatment fasting glucose levels were slightly lower than pre-treatment levels in 5 of the 6 subjects. MMSE and ADASCog values also varied between visits, but as a group no consistent changes in the MMSE or ADASCog scores were observed during the course of the study (Table 3). The average visit 1 and 2 MMSE scores (with standard deviations) were, respectively, 21.2 ± 4.7 and 19.5 ± 5.9. The average visit 1 and visit 2 ADASCog scores were 21.5 ± 5.1 and 23.7 ± 6.6 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Weight, fasting glucose, fasting insulin, HOMA-IR, MMSE, and ADASCog data. V1 = visit 1; V2 = visit 2.

| Subject | Weight (kg) |

Glucose |

Insulin |

HOMA-IR |

MMSE |

ADASCog |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1 | V2 | V1 | V2 | V1 | V2 | V1 | V2 | V1 | V2 | V1 | V2 | |

| 1 | 72.9 | 74.3 | 105 | 104 | 7.2 | 6.9 | 1.87 | 1.77 | 28 | 28 | 15 | 18 |

| 2 | 86.2 | 83.5 | 107 | 101 | 25.5 | 14.6 | 6.73 | 3.64 | 21 | 18 | 23 | 28 |

| 3 | 78.3 | 81.1 | 104 | 100 | 21.2 | 24.1 | 5.44 | 5.95 | 25 | 25 | 17 | 14 |

| 4 | 70.0 | 68.1 | 99 | 91 | 6.4 | 5.5 | 1.56 | 1.24 | 18 | 12 | 26 | 28 |

| 5 | 88.4 | 87.6 | 140 | 124 | 10.0 | 6.7 | 3.46 | 2.05 | 15 | 18 | 28 | 23 |

| 6 | 76.4 | 78.1 | 100 | 105 | 2.8 | 3.9 | 0.69 | 1.01 | 20 | 16 | 20 | 31 |

Quantitative plasma amino acid profiles were performed by Mayo Clinical Labs and included measurements of 42 amino acids and derivatives. Values from the visit 1 and 2 values were compared, and using a p value cut-off of 0.05 no statistically significant inter-visit differences were observed (Table 4). Values for two amino acids (glutamate and aspartate) most directly linked to OAA metabolism (as glutamate reacts with OAA to from aspartate and α-ketoglutarate) did not show statistically significant inter-visit changes. Levels of alanine, which is in equilibrium with pyruvate (a decarboxylation product of OAA), also did not change across the visits (Table 4).

Table 4.

Plasma amino acid measurements. V1 = visit 1; V2 = visit 2.

| Subject | Glutamate |

Aspartate |

Alanine |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1 | V2 | V1 | V2 | V1 | V2 | |

| 1 | 29 | 45 | 1 | 3 | 451 | 343 |

| 2 | 74 | 51 | 4 | 3 | 562 | 617 |

| 3 | 50 | 49 | 2 | 3 | 326 | 479 |

| 4 | 20 | 16 | 2 | 2 | 261 | 285 |

| 5 | 27 | 33 | 2 | 2 | 474 | 374 |

| 6 | 36 | 43 | 2 | 2 | 338 | 407 |

For PK measurements performed using the enzymatic-based OAA quantification kit, the more sensitive fluorescence-based approach was confounded either by plasma auto-fluorescence at the critical excitation/emission wavelengths or else through a non-specific, activating interaction between plasma and kit components. No useful data were obtained using this approach. The kit's absorbance-based approach was therefore utilized. The absorbance method has a ten-fold reduction in sensitivity as compared to the fluorescence assay, and the levels of OAA detected were very near the limit of detection for the method. Qualitative review of some of the data from this analysis indicates a possible Tmax peak occurs between 1 and 1.5 h after ingestion of a 100 mg capsule (data not shown). This pattern, though, was not consistently observed across subjects.

The attempts to measure OAA by the coupled enzyme assay consumed the acquired plasma samples from subject 2. Plasma samples for the remaining 5 subjects were analyzed by LC–MS/MS for both OAA and pyruvate. OAA concentrations for subject 1 were at or below our limit of quantitation (10 ng/ml), so the results from that patient were not included in the determination of PK parameters. All subjects showed quantifiable pyruvate concentrations.

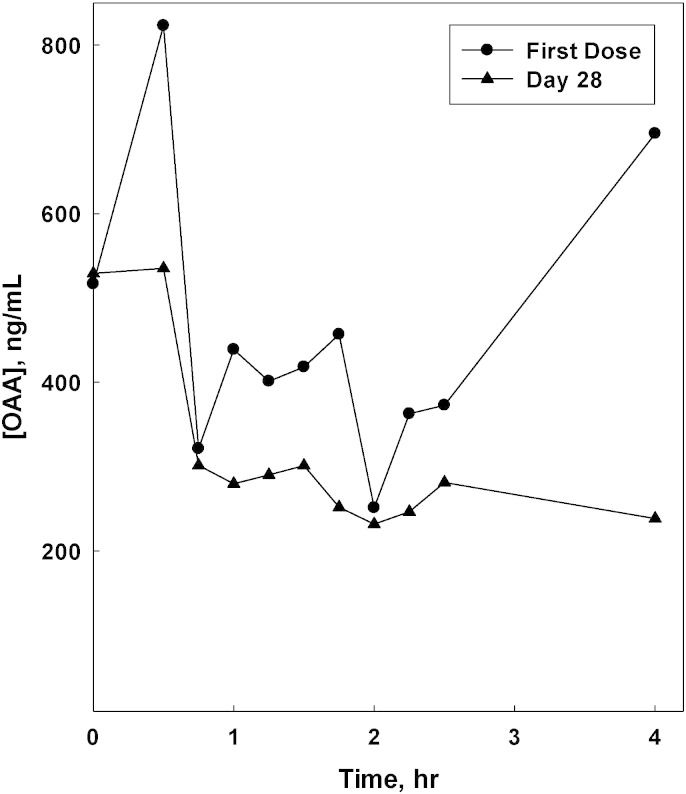

Representative PK data are shown in Fig. 2. The plasma concentration versus time plots in the figure does not show typical PK behavior. The pre-dose OAA concentrations were about 60% of the observed Cmax for the first dose of OAA, and the pre-dose concentration and Cmax were virtually identical for the Day 28 dose. Neither day exhibited the expected absorption and clearance phases in the time course. It is also apparent that for this subject no accumulation of OAA was seen following the 28 days of dosing. The compiled observations for OAA and pyruvate for the LC–MS/MS-analyzed subjects are shown in Table 5. It is apparent that Cmax and Tmax values were quite variable, but it is important to note that the Tmax for OAA was centered on 1.2 h after dosing. The ratio of Cmax to the pre-dose OAA concentration (C0) underscores that the increases in plasma OAA concentrations following this 100 mg dose were quite small relative to the observed basal concentrations. Our observations for possible effects on pyruvate concentrations mirrored the results seen for OAA, with the exception of a later Tmax (2.6 h).

Fig. 2.

OAA plasma concentration versus time. Results are shown for the analysis of plasma samples from subject 3.

Table 5.

OAA and pyruvate PK parameters. Reported values are mean ± standard deviation of individual patient values, with ranges in parentheses. Since no significant differences or trends were observed between the first-dose and steady-state values for these patients the values from both PK days were included. N = total number of PK sample sets included.

| Cmax, ng/ml | Tmax, h | Cmax/C0 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OAA (n = 8) | 551 ± 241 (210–1122) | 1.2 ± 0.7 (0.5–2.5) | 1.4 ± 0.5 (1.0–2.1) |

| Pyruvate (n = 10) | 11,964 ± 7979 (3144–21,122) | 2.1 ± 1.5 (0.5–4.0) | 1.4 ± 0.8 (1.0–3.3) |

4. Discussion

Over a one month period 100 mg of OAA, taken twice per day, was well tolerated by AD subjects and appeared to be safe. Cognitive performance did not improve over the 1-month treatment period, although it must be noted that this study was neither designed nor intended to reveal changes in cognitive performance. Indeed, the initial visit cognitive data were obtained after subjects had taken their first OAA capsule.

The 100 mg dose did not yield consistent changes in either OAA or pyruvate levels. Our ability to detect consistent changes was likely hindered by high background levels of OAA and pyruvate, which may have obscured genuine treatment-induced changes. Regardless, our data suggest 100 mg of OAA does not significantly change an individual AD subject's plasma level. Failure to detect any reliable treatment-induced amino acid changes is potentially consistent with but does not prove this possibility.

We are aware of only one other published OAA clinical study, which was reported in 1968 [14]. In that study the author tested the oral hypoglycemic effect of OAA in diabetic subjects and found it was well-tolerated at doses ranging from 100 to 1000 mg per day (administered in divided doses), and for durations ranging from 5 to 44 days (the 1000 mg per day dose was only tested for 5 days). Based on comparisons between pre and post-treatment fasting blood sugar levels, it was concluded that OAA did have a hypoglycemic effect. While we did not detect a similar effect, it is important to note that we studied AD subjects who did not carry a diabetes diagnosis and had lower blood sugars, the OAA doses we evaluated were lower than those tested in the majority of the diabetic subjects, and the absolute glucose readings from visit 2 were slightly lower than the visit 1 readings in 5 of our 6 subjects.

The 1968 study also reported limited PK data. Levels were not increased 30 min but were increased 60 min after 200 mg was orally administered to three subjects. On average, blood OAA levels rose from 0 ng/ml to 23 ng/ml. Clearly, both the basal and the peak OAA concentrations we report here are far higher than those related in the previous study. That study used different methods to measure OAA concentrations. No details were provided regarding the validation of the method, including the specificity of the assay and the range of detection and quantification. Without knowledge of the validated specificity and sensitivity of the previous analytical method we cannot compare the measured values from the two studies, although we would assume our LC–MS/MS approach should have greater sensitivity and specificity than the derivatization and colorimetric approach described in the earlier study.

In addition to being proposed for the treatment of AD and diabetes, recent preclinical research has also identified OAA as a potential therapeutic agent for stroke, traumatic brain injury, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and glioma [15], [16], [17], [18]. The clinical safety data we now report should prove relevant to efforts intending to translate results from these preclinical studies to the clinical arena. Our study also informs our attempts to develop OAA as a treatment for AD. Overall, we conclude that although OAA 100 mg capsules twice per day for one month are safe in AD subjects, because a consistent and clear increase in the OAA plasma level was not observed future clinical studies need to evaluate higher doses.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Transparency document

Transparency document.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Frontiers: The Heartland Center for Clinical and Translational Research of the Kansas University Medical Center (NCATS #UL1TR000001), the University of Kansas Alzheimer's Disease Center (P30AG035982), the University of Kansas Cancer Center (P30CA168524), and the University of Kansas Medical Center Landon Center on Aging.

Footnotes

The Transparency document associated with this article can be found, in the online version

References

- 1.Swerdlow R.H. Pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Clin. Interv. Aging. 2007;2:347–359. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swerdlow R.H. Mitochondria and cell bioenergetics: increasingly recognized components and a possible etiologic cause of Alzheimer's disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2012;16:1434–1455. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Leon M.J., Ferris S.H., George A.E., Christman D.R., Fowler J.S., Gentes C., Reisberg B., Gee B., Emmerich M., Yonekura Y., Brodie J., Wolf Kricheff A.P., II Positron emission tomographic studies of aging and Alzheimer disease, AJNR. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1983;4:568–571. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foster N.L., Chase T.N., Fedio P., Patronas N.J., Brooks R.A., Di Chiro G. Alzheimer's disease: focal cortical changes shown by positron emission tomography. Neurology. 1983;33:961–965. doi: 10.1212/wnl.33.8.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedland R.P., Budinger T.F., Ganz E., Yano Y., Mathis C.A., Koss B., Ober B.A., Huesman R.H., Derenzo S.E. Regional cerebral metabolic alterations in dementia of the Alzheimer type: positron emission tomography with [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 1983;7:590–598. doi: 10.1097/00004728-198308000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirai K., Aliev G., Nunomura A., Fujioka H., Russell R.L., Atwood C.S., Johnson A.B., Kress Y., Vinters H.V., Tabaton M., Shimohama S., Cash A.D., Siedlak S.L., Harris P.L., Jones P.K., Petersen R.B., Perry G., Smith M.A. Mitochondrial abnormalities in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:3017–3023. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-09-03017.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheng B., Wang X., Su B., Lee H.G., Casadesus G., Perry G., Zhu X. Impaired mitochondrial biogenesis contributes to mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurochem. 2012;120:419–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07581.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swerdlow R.H. Bioenergetic medicine. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2014;171:1854–1869. doi: 10.1111/bph.12394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swerdlow R.H., Burns J.M., Khan S.M. The Alzheimer's disease mitochondrial cascade hypothesis: progress and perspectives. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1842:1219–1231. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilkins H.M., Koppel S., Carl S.M., Ramanujan S., Weidling I., Michaelis M.L., Michaelis E.K., Swerdlow R.H. Oxaloacetate enhances neuronal cell bioenergetic fluxes and infrastructure. J. Neurochem. 2016 doi: 10.1111/jnc.13545. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilkins H.M., Harris J.L., Carl S.M., L. E, Lu J., Selfridge J. Eva, Roy N., Hutfles L., Koppel S., Morris J., Burns J.M., Michaelis M.L., Michaelis E.K., Brooks W.M., Swerdlow R.H. Oxaloacetate activates brain mitochondrial biogenesis, enhances the insulin pathway, reduces inflammation and stimulates neurogenesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014;23:6528–6541. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKhann G.M., Knopman D.S., Chertkow H., Hyman B.T., Jack C.R., Jr., Kawas C.H., Klunk W.E., Koroshetz W.J., Manly J.J., Mayeux R., Mohs R.C., Morris J.C., Rossor M.N., Scheltens P., Carrillo M.C., Thies B., Weintraub S., Phelps C.H. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan B., Lu Z., Dong S., Zhao G., Kuo M.S. Derivatization of the tricarboxylic acid intermediates with O-benzylhydroxylamine for liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry detection. Anal. Biochem. 2014;465:134–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2014.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshikawa K. Studies on the anti-diabetic effect of sodium oxaloacetate. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 1968;96:127–141. doi: 10.1620/tjem.96.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campos F., Sobrino T., Ramos-Cabrer P., Castillo J. Oxaloacetate: a novel neuroprotective for acute ischemic stroke. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2012;44:262–265. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruban A., Berkutzki T., Cooper I., Mohar B., Teichberg V.I. Blood glutamate scavengers prolong the survival of ats and ice with rain-mplanted gliomas. Investig. New Drugs. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10637-012-9794-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zlotnik A., Sinelnikov I., Gruenbaum B.F., Gruenbaum S.E., Dubilet M., Dubilet E., Leibowitz A., Ohayon S., Regev A., Boyko M., Shapira Y., Teichberg V.I. Effect of glutamate and blood glutamate scavengers oxaloacetate and pyruvate on neurological outcome and pathohistology of the hippocampus after traumatic brain injury in rats. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:73–83. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31823d7731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruban A., Malina K.C., Cooper I., Graubardt N., Babakin L., Jona G., Teichberg V.I. Combined treatment of an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis rat model with recombinant GOT1 and oxaloacetic acid: a novel neuroprotective treatment. Neurodegener Dis. 2015;15:233–242. doi: 10.1159/000382034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Transparency document.