Abstract

Objectives:

Reduced vitamin E levels have been reported in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), but no conclusive data on patients with simple steatosis (SS) are available. Aim of this study was to investigate the association between serum vitamin E levels and SS.

Methods:

A cohort of 312 patients with cardio-metabolic risk factors was screened for liver steatosis by ultrasonography (US). We reasonably classified as SS patients with US-fatty liver, normal liver function tests (LFTs) and with Cytokeratin 18 <246 mIU/ml. Liver biopsy was performed in 41 patients with US-fatty liver and persistent elevation of LFTs (>6 months). Serum cholesterol-adjusted vitamin E (Vit E/chol) levels were measured.

Results:

Mean age was 53.9±12.5 years and 38.4% were women. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) was detected at US in 244 patients; of those 39 had biopsy-proven NASH and 2 borderline NASH. Vit E/chol was reduced in both SS (3.4±2.0, P<0.001), and NASH (3.5±2.1, P=0.006) compared with non-NAFLD patients (4.8±2.0 μmol/mmol chol). No difference was found between SS and NASH (P=0.785). After excluding patients with NASH, a multivariable logistic regression analysis found that Vit E/chol (odds ratio (OR): 0.716, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.602–0.851, P<0.001), alanine aminotransferase (ALT, OR: 1.093, 95% CI 1.029–1.161, P=0.004), body mass index (OR: 1.162, 95% CI 1.055–1.279, P=0.002) and metabolic syndrome (OR: 5.725, 95% CI 2.247–14.591, P<0.001) were factors independently associated with the presence of SS.

Conclusions:

Reduced vitamin E serum levels are associated with SS, with a similar reduction between patients with SS and NASH, compared with non-NAFLD patients. Our findings suggest that the potential benefit of vitamin E supplementation should be investigated also in patients with SS.

Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most frequent and emerging liver disease in the general population.1 The management of NAFLD has become a major clinical challenge to healthcare practitioners.2 The term NAFLD includes different liver clinical conditions ranging from simple steatosis (SS) to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), eventually progressing to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.3 Mechanisms underlying progression from SS to NASH or cirrhosis remain poorly understood.

Oxidative stress seems to be one of the factors responsible for the occurrence of liver damage and for the progression to cirrhosis.4, 5 Several markers of oxidative stress have been measured so far in NAFLD patients with mixed results.6 Particular attention have been focused on vitamin E, which is an important lipid-soluble vitamin exerting an antioxidant effect acting as free radical scavenger,7 and protecting cell membranes and lipoproteins from lipid peroxidation. Vitamin E is considered a good index of the antioxidant status, as it has been shown to be inversely correlated with markers of oxidative stress.8, 9

In the context of NAFLD, vitamin E has been found to be reduced in patients with NASH, and findings from the PIVENS trial10 suggested that vitamin E supplementation was effective in improving liver histology in patients with NASH. Nevertheless, the association between vitamin E levels and the severity of NASH was not confirmed by other studies.6, 11, 12, 13

One particular aspect of this problem concerns whether a reduction in the levels of vitamin E may also occur in patients with SS, i.e., before the onset of NASH. So far, no study has explored this issue.

The aim of our study was to examine the association between the serum levels of vitamin E and the presence of SS in a cohort of patients with cardio-metabolic risk factors.

Methods

The study included 312 consecutive outpatients presenting with cardio-metabolic risk factors, referring to the Day Service of Internal Medicine at the Umberto I—University Hospital in Rome from February 2011 to September 2013. At baseline, anthropometric data including waist circumference, height and weight were recorded and body mass index (BMI) was calculated for each patient. Routine clinical and biochemical evaluation and ultrasonography (US) examination for liver steatosis were obtained for all patients.

Inclusion criteria were: US evidence of fatty liver (see below), no history of current or past excessive alcohol drinking as defined by an average daily consumption of alcohol >20 g; negative tests for the presence of hepatitis B surface antigen and antibody to hepatitis C virus. Exclusion criteria were: presence of cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases, current supplementation with antioxidants or vitamins.

Cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors were defined as follows: arterial hypertension as repeated elevated blood pressure values (≥140/≥90 mm Hg) or taking antihypertensive drugs;14 diabetes as the presence of symptoms of diabetes and a casual plasma glucose ≥200 mg/dl (11.1 mmol/l), or fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dl (7.0 mmol/l), or presence of anti-diabetic treatment.15 Metabolic syndrome (MetS) was classified according to the modified criteria of the Adult Treatment Panel III Expert Panel of the National Cholesterol Education Program.16

All patients provided written informed consent. The study protocol was approved by the local ethical board of Sapienza University of Rome and was carried out according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.17

Blood Collection and laboratory analyses

After overnight, fasting and supine rest for at least 10 min, blood was withdrawn from the antecubital vein. Serum was divided into aliquots and stored at −80 °C until assays were performed.

Patients underwent routine laboratory analyses including aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), fasting blood glucose, and lipid profile (total cholesterol, low density lipoprotein, high-density lipoprotein, and triglycerides).

Vitamin E

Serum levels of vitamin E (α-tocopherol) were measured by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography.18 Serum samples (100 μl) were supplemented with tocopheryl acetate (internal standard), deproteinized by the addition of ethanol, and extracted with hexane. Phase separation was achieved by centrifugation. The collected upper phase was evaporated and analyzed using an Agilent 1200 Infinity series High-Performance Liquid Chromatography system equipped with an Eclipse Plus C18 column (4.6 × 100 mm). Vitamin E serum levels were expressed as ratio between serum α-tocopherol concentration (μmol/l) and serum total cholesterol concentration (mmol/l) (Vit E/chol, μmol/mmol), which better expresses the circulating levels of vitamin E.19

Cytokeratin 18-M30 (CK-18)

Serum levels of CK-18 were measured as marker of liver damage with a commercial immunoassay (Tema Ricerca, Italy) and expressed as mlU/ml, as previously reported.5 Intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients were 6 and 7%, respectively.

Assessment of liver steatosis

We performed liver US to assess the presence of steatosis. All US were performed by the same operator who was blinded to laboratory values using a GE VividS6 (GE Healthcare, Wauwatosa, WI) apparatus equipped with a convex 3.5 MHz probe. Liver steatosis was defined according to Hamaguchi criteria based on the presence of abnormally intense, high-level echoes arising from the hepatic parenchyma, liver–kidney difference in echo amplitude, echo penetration into deep portion of the liver and clarity of liver blood vessel structure.20, 21 Steatosis was assessed semi-quantitatively on a scale of 0–6, defining 4 classes of liver steatosis degree: 0 absent; 1,2 mild; 3,4 moderate; and 5,6 severe.

We reasonably classified as SS patients with US evidence of liver steatosis and normal liver function tests (LFTs, ALT ≤35 U/L and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase ≤36 U/L) and with a value of CK-18 <246 mIU/ml. This value for the diagnosis of NASH was taken from a multicentre validation study previously published by Feldstein et al.22 where the value of 246 mIU/ml showed the best combination of sensitivity (75%) and specificity (81%).

Liver histology

Percutaneous US-guided liver biopsy was performed in NAFLD patients with persistent elevation of liver enzymes (>6 months). Liver biopsy was conducted under conscious sedation using a 16-gauge Klatskin needle. Liver fragments were fixed in buffered formalin for 2–4 h and embedded in paraffin with a melting point of 55–57 °C. Three- to four-lm sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin and Masson's trichrome stains. A single pathologist blinded to identity, history, and biochemistry of patients analyzed all the slides. A minimum biopsy specimen length of 15 mm or at least the presence of 10 complete portal tracts was required. Liver biopsy specimens were classified as to “definite NASH” (with a NAFLD activity score (NAS) ≥5),23 “borderline NASH”24 and “not NASH”.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were reported as counts (percentage); continuous variables were expressed as mean±s.d. or median and interquartile range. Normal distribution of parameters was assessed by Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Student unpaired t-test and Pearson correlation analysis were used for normally distributed continuous variables. Appropriate nonparametric tests (Mann–Whitney U-test and Spearman rank correlation test) were employed for all the other variables. Group comparisons were performed using Fisher's F-test (Analysis of variance) or Kruskall–Wallis test when needed.

After excluding patients with NASH, logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the association between SS and Vit E/chol, and after adjustment for MetS, age, female gender, smoking, GGT, ALT, AST, statins, and BMI.

Variables were entered with a forced procedure method (one step) and we used the composite variable of MetS instead of its single components (which were excluded from the model).

All tests were two-tailed and a statistical significance was set at a P value of <0.05. Analyses were performed using computer software packages (IBM SPSS Statistics v20.0, Armonk, NY).

Results

Clinical and biochemical characteristics are listed in Table 1. In the whole population, mean age was 53.9±12.5 years and 38.4% were women; 59.2% of patients were affected by MetS. A diagnosis of US liver steatosis was made in 262 (84.0%) of the 312 screened patients. Based on CK-18 values, we excluded 18 patients with US liver steatosis who had normal LFTs but high values of CK-18 (≥246 mIU/ml). Thus, 244 patients with steatosis were used for the analysis. Of these, 22.2% had mild, 41.9% moderate and 35.5% severe steatosis at US.

Table 1. Clinical and serological characteristics of patients.

| non-NAFLD (n=50) | Simple steatosis (n=203) | P valuea | NASH/borderline NASH (n=41) | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 55.0±13.5 | 55.1±12.1 | 0.996 | 47.0±11.5 | 0.007 |

| Women (%) | 36.0 | 37.4 | 0.850 | 46.3 | 0.392 |

| Smoking (%) | 28.0 | 20.7 | 0.260 | 34.1 | 0.649 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.7±3.6 | 31.5±5.7 | <0.001 | 30.0±4.6 | 0.126 |

| Arterial hypertension (treated) (%) | 68.0 | 65.5 | 0.868 | 39.0 | 0.007 |

| Diabetes (%) | 16.0 | 30.5 | 0.026 | 26.8 | 0.300 |

| Statins (%) | 38.0 | 35.0 | 0.742 | 29.3 | 0.505 |

| Metabolic syndrome (%) | 25.0 | 69.0 | <0.001 | 53.7 | 0.005 |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mg/dl) | 96.7±22.5 | 109.3±36.2 | 0.017 | 101.7±34.7 | 0.491 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 202.6±44.0 | 200.6±39.4 | 0.749 | 192.7±34.7 | 0.693 |

| LDL-c (mg/dl) | 123.2±39.4 | 119.4±34.0 | 0.478 | 114.0±30.1 | 0.628 |

| HDL-c (mg/dl) | 55.7±16.8 | 48.5±13.7 | 0.010 | 49.1±22.4 | 0.139 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 117.5±66.2 | 169.9±125.3 | 0.008 | 150.0±99.6 | 0.503 |

| Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidaseb (U/l) | 21.0 (14.0–28.0) | 23.0 (17.0–34.0) | 0.032 | 52.0 (34.0–138.5) | <0.001 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/l) | 20.0±8.1 | 26.9±9.4 | 0.031 | 78.8±39.3 | <0.001 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/l) | 19.5±5.9 | 21.4±7.8 | 0.315 | 47.9±27.6 | <0.001 |

| CK-18 M30b (mIU/ml) | 100.0 (80.0–125.0) (min 60.0–max 150) | 176.0 (145.0–190.0) (min 51.0–max 245.0) | <0.001 | 266.0 (250.0–284.7) (min 247–max 308.0) | <0.001 |

CK-18, cytokeratin 18; HDL-c, high-density lipoprotein; LDL-c, low density lipoprotein; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.

vs. non-NAFLD patients.

Data are expressed as median and interquartile range.

In 41 of the 244 NAFLD patients, we observed a persistent elevation of LFTs. These patients, 22 males and 19 females, underwent liver biopsy, which revealed in 39 cases the presence of NASH and in 2 borderline NASH.

A significant difference between patients with and without SS was observed for BMI, MetS, and diabetes (Table 1). SS patients had significantly higher mean values of fasting plasma glucose, and triglycerides, while high-density lipoprotein cholesterol values were significantly reduced (Table 1). Concerning serum markers of liver damage ALT and GGT were significantly higher in patients with SS compared with those without (Table 1).

Moreover, a progressive higher value of CK-18 was detected from patients without fatty liver, to those with SS and NASH [100.0 (80.0–125.0), 176.0 (145.0–190.0), 266.0 (250.0–284.7) mIU/ml, respectively, P<0.001 NAFLD vs. SS, P<0.001 SS vs. NASH].

Patients with NASH were younger, less affected by arterial hypertension, with a higher prevalence of MetS and a significant elevation of LFTs (Table 1) compared with NAFLD patients.

Vitamin E levels

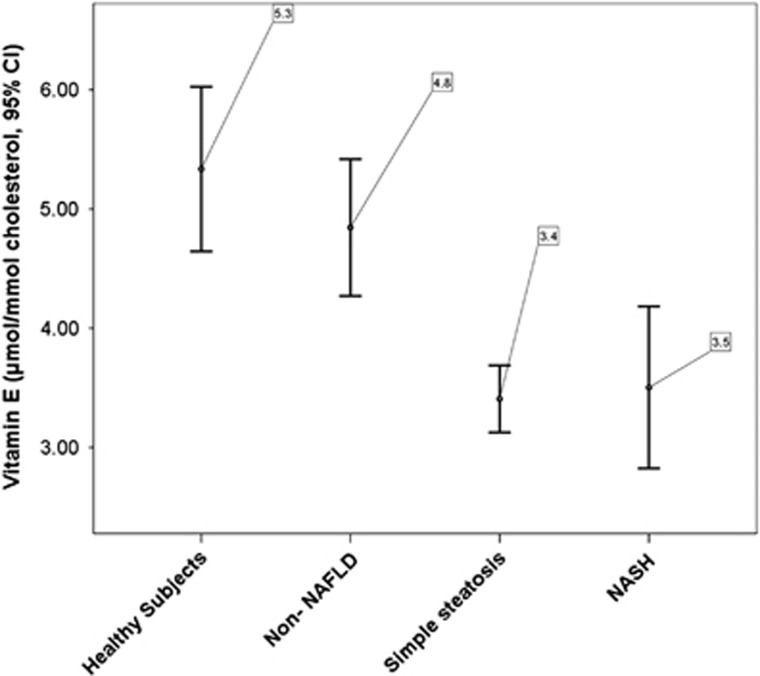

To establish normal values of Vit E/chol we included a control group of 20 healthy subjects (HSs, 13 men and 7 women) from the same geographic area. HSs had normal weight and no alterations in lipid profile or LFTs and were not taking any drug or supplement. Differently from the group of non-NAFLD patients, HSs had no cardio-metabolic risk factors. Mean value of serum Vit E/chol in HSs was 5.3±1.5 μmol/mmol (Figure 1). Subjects with SS showed significantly lower mean values of serum Vit E/chol when compared with HSs (P<0.001) and to non-NAFLD patients (P<0.001) (Figure 1). Similarly, reduced Vit E/chol values were obtained in the subgroup of 41 NASH/borderline NASH patients (P=0.006 vs. NAFLD). No difference was found between patients with SS and those with NASH/borderline NASH (P=0.785). Vit E/chol and CK-18 were inversely correlated (Rs:−0.185, P=0.004).

Figure 1.

Mean values of vitamin E/cholesterol.

Determinants of simple steatosis

To assess the association between SS and Vit E/chol, we performed a multivariable logistic regression analysis, after excluding the 41 patients with NASH/borderline NASH. We found that Vit E/chol (odds ratio (OR): 0.716, P<0.001), ALT (OR: 1.093, P=0.004), BMI (OR: 1.162, P=0.002) and MetS (OR: 5.725, P<0.001) were factors independently associated with the presence of SS (Table 2).

Table 2. Multiple logistic regression analysis of determinants of simple steatosis.

| OR | 95% CI | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin E/cholesterol | 0.716 | 0.602 | 0.851 | <0.001 |

| Statins | 0.721 | 0.297 | 1.752 | 0.471 |

| Smoking | 0.651 | 0.255 | 1.664 | 0.370 |

| Age | 0.978 | 0.944 | 1.012 | 0.203 |

| Female | 0.955 | 0.401 | 2.275 | 0.917 |

| Body mass index | 1.162 | 1.055 | 1.279 | 0.002 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 1.001 | 0.938 | 1.068 | 0.985 |

| Alanine aminotransferase | 1.093 | 1.029 | 1.161 | 0.004 |

| Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase | 0.995 | 0.975 | 1.016 | 0.654 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 5.725 | 2.247 | 14.591 | <0.001 |

| Constant | 0.058 | 0.123 | ||

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Discussion

We provide evidence that reduced serum vitamin E levels are independently associated with the presence of SS in a cohort of patients with cardio-metabolic risk factors.

Clinical studies so far have analyzed serum vitamin E levels of patients with NASH in comparison with HSs,6, 11, 12, 13 and no data on patients with SS are available.

We reasonably classified as SS patients with presence of fatty liver at US, normal LFTs and low CK-18 (<246 mIU/ml). Although this classification is not completely accurate, it reflects common clinical practice, which does not allow to perform liver biopsy in all patients with US evidence of liver steatosis and normal liver biomarkers. In fact, liver biopsy should be considered only for NAFLD patients at increased risk to have NASH, and who would most benefit from histologic diagnosis to guide therapeutic approach.10 Moreover, in asymptomatic patients with hepatic steatosis detected on imaging and normal liver biochemistry, a liver biopsy cannot be recommended.10

A peculiarity of our study is also in the presence of a control group of patients with cardio-metabolic risk factors but without liver steatosis at US. This allows a better analysis of the association between the presence of NAFLD and the reduction of vitamin E levels. In fact, NAFLD is strongly associated with MetS,25, 26 and it could be possible that the reduced Vit E/chol in NAFLD mirrors the coexistence of MetS.

We found that serum vitamin E levels, along with ALT, BMI, and MetS, were factors associated with the presence of SS. The independent association between SS and Vit E/chol suggests that other mechanisms than MetS may account for the inverse association between liver steatosis and Vit E/chol.

An interesting finding of our study is the similar reduction of Vit E/chol levels in patients with SS and in those with biopsy-proven NASH, compared with NAFLD patients.

This comparable reduction of vitamin E is intriguing, but of difficult pathophysiologic explanation, given the difference in the natural history of SS and NASH. Our findings suggest that patients with NAFLD may have an early enhanced systemic oxidative stress, which leads to a reduction in natural antioxidant pool, including vitamin E. However, in the present study we cannot establish whether the imbalance of the oxidant status may directly contribute to the progression from SS to NASH.

Moreover, differently from previous studies, we expressed values of vitamin E after adjustment for total serum cholesterol. This is important, since the plasma concentration of fat-soluble vitamins, such as vitamin E, varies with the amount of plasmatic lipids, and thus requires lipid standardization, especially in conditions likely to raise serum cholesterol.19

The high percentage of NASH at liver biopsy is only partially surprising. In fact, the reported rate of biopsy-proven NASH is highly variable, and can reach 40% in unselected patients without known liver disease, as reported in a Greek study on 600 autopsies.1 In our study, patients who underwent liver biopsy had all persistent elevation of LFTs for at least 6 months, and more than 50% suffered from MetS with a mean BMI of 30 kg/m2; all these conditions are strictly associated with the presence of NASH.27, 28 This finding supports the high prevalence of NASH in high-risk patients with cardio-metabolic disorders.

Our study has a number of limitations. We detected fatty liver by US, a qualitative method, inadequate to quantify <30% liver fat content. Nevertheless, US is safe and inexpensive and uses standardized criteria to define liver steatosis.21 Moreover, the separation of SS from NASH is difficult with non-invasive methods, and the presence of NASH is underestimated given the possibility to perform liver biopsy only in patients with persistent abnormalities in LFTs. Serum CK-18 levels were measured to reduce this potential classification bias. However, even if the cutoff of CK-18 used in our study for the discrimination of patients with SS from those with NASH derives from a multicentre study, it is not currently recommended for the non-invasive diagnosis of NASH.

The study may have some implications. Considering that low levels of vitamin E are associated with increased cardiovascular risk,29, 30, 31, 32 our findings may further support the role of NAFLD as cardiovascular risk factor. In this context, statins could be a promising therapeutic approach, as they increase serum vitamin E,8, 33, 34 and improve liver steatosis.35

In conclusion, we found that patients with SS and those with biopsy-proven NASH have a similar reduction of serum levels of Vit E/chol compared with non-NAFLD patients, suggesting that oxidative stress imbalance could occur in the early stages of fatty liver disease.

Study Highlights

Guarantor of the article: Francesco Angelico, MD.

Specific author contributions: Pastori Daniele: study concept and design. Analysis and interpretation of data. Drafting of the manuscript. Critical revision of the manuscript. Approved the final draft submitted. Baratta Francesco: study concept and design. Acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. Approved the final draft submitted. Carnevale Roberto: study concept and design. Acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. Approved the final draft submitted. Cangemi Roberto: interpretation of data. Drafting of the manuscript. Critical revision of the manuscript. Approved the final draft submitted. Del Ben Maria: acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. Critical revision of the manuscript. Approved the final draft submitted. Polimeni Licia: acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. Critical revision of the manuscript. Approved the final draft submitted. Labbadia Giancarlo: acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. Critical revision of the manuscript. Approved the final draft submitted. Nocella Cristina: interpretation of data. Drafting of the manuscript. Critical revision of the manuscript. Approved the final draft submitted. Scardella Laura: interpretation of data. Drafting of the manuscript. Critical revision of the manuscript. Approved the final draft submitted. Pani Arianna: Interpretation of data. Drafting of the manuscript. Critical revision of the manuscript. Approved the final draft submitted. Pignatelli Pasquale: interpretation of data. Drafting of the manuscript. Critical revision of the manuscript. Approved the final draft submitted. Francesco Violi: interpretation of data. Drafting of the manuscript. Critical revision of the manuscript. Approved the final draft submitted. Francesco Angelico: interpretation of data. Drafting of the manuscript. Critical revision of the manuscript. Approved the final draft submitted.

Financial support: None.

Potential competing interests: None.

References

- Vernon G, Baranova A, Younossi ZM. Systematic review: the epidemiology and natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011; 34: 274–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratziu V, Goodman Z, Sanyal A. Current efforts and trends in the treatment of NASH. J Hepatol 2015; 62: S65–S75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano Y, Cohen DE. Mechanisms of hepatic triglyceride accumulation in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Gastroenterol 2013; 48: 434–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angulo P. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 1221–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Ben M, Polimeni L, Carnevale R et al. NOX2-generated oxidative stress is associated with severity of ultrasound liver steatosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMC Gastroenterol 2014; 14: 81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koek GH, Liedorp PR, Bast A. The role of oxidative stress in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Clin Chim Acta 2011; 412: 1297–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh U, Devaraj S, Jialal I. Vitamin E, oxidative stress, and inflammation. Annu Rev Nutr 2005; 25: 151–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cangemi R, Loffredo L, Carnevale R et al. Early decrease of oxidative stress by atorvastatin in hypercholesterolaemic patients: effect on circulating vitamin E. Eur Heart J 2008; 29: 54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Ben M, Angelico F, Cangemi R et al. Moderate weight loss decreases oxidative stress and increases antioxidant status in patients with metabolic syndrome. ISRN Obes 2012; 2012: 960427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE et al. The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, and the American Gastroenterological Association. Hepatology 2012; 55: 2005–2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahcecioglu IH, Yalniz M, Ilhan N et al. Levels of serum vitamin A, alpha-tocopherol and malondialdehyde in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: relationship with histopathologic severity. Int J Clin Pract 2005; 59: 318–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado MV, Ravasco P, Jesus L et al. Blood oxidative stress markers in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and how it correlates with diet. Scand J Gastroenterol 2008; 43: 95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavine JE, Schwimmer JB, Van Natta ML et al. Effect of vitamin E or metformin for treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children and adolescents: the TONIC randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2011; 305: 1659–1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K et al. 2013 Practice guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC): ESH/ESC Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension. J Hypertens 2013; 31: 1925–1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Authors/Task Force M, Ryden L, Grant PJ et al. ESC Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD: The Task Force on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and developed in collaboration with the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Eur Heart J 2013; 34: 3035–3087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation 2005; 112: 2735–2752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Bull World Health Organ 2001; 79: 373–374. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieri JG, Tolliver TJ, Catignani GL. Simultaneous determination of alpha-tocopherol and retinol in plasma or red cells by high pressure liquid chromatography. Am J Clin Nutr 1979; 32: 2143–2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traber MG, Jialal I. Measurement of lipid-soluble vitamins—further adjustment needed? Lancet 2000; 355: 2013–2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saverymuttu SH, Joseph AE, Maxwell JD. Ultrasound scanning in the detection of hepatic fibrosis and steatosis. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986; 292: 13–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamaguchi M, Kojima T, Itoh Y et al. The severity of ultrasonographic findings in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease reflects the metabolic syndrome and visceral fat accumulation. Am J Gastroenterol 2007; 102: 2708–2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein AE, Wieckowska A, Lopez AR et al. Cytokeratin-18 fragment levels as noninvasive biomarkers for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a multicenter validation study. Hepatology 2009; 50: 1072–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van Natta M et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2005; 41: 1313–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, Wilson LA et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) activity score and the histopathologic diagnosis in NAFLD: distinct clinicopathologic meanings. Hepatology 2011; 53: 810–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelico F, Del Ben M, Conti R et al. Insulin resistance, the metabolic syndrome, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005; 90: 1578–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonardo A, Ballestri S, Marchesini G et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a precursor of the metabolic syndrome. Dig Liver Dis 2015; 47: 181–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anty R, Iannelli A, Patouraux S et al. A new composite model including metabolic syndrome, alanine aminotransferase and cytokeratin-18 for the diagnosis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in morbidly obese patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010; 32: 1315–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma S, Jensen D, Hart J et al. Predictive value of ALT levels for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and advanced fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Liver Int 2013; 33: 1398–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cangemi R, Pignatelli P, Carnevale R et al. Cholesterol-adjusted vitamin E serum levels are associated with cardiovascular events in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol 2013; 168: 3241–3247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stampfer MJ, Hennekens CH, Manson JE et al. Vitamin E consumption and the risk of coronary disease in women. N Engl J Med 1993; 328: 1444–1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Ascherio A et al. Vitamin E consumption and the risk of coronary heart disease in men. N Engl J Med 1993; 328: 1450–1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastori D, Loffredo L, Perri L et al. Relation of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and framingham risk score to flow-mediated dilation in patients with cardiometabolic risk factors. Am J Cardiol 2015; 115: 1402–1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cangemi R, Loffredo L, Carnevale R et al. Statins enhance circulating vitamin E. Int J Cardiol 2008; 123: 172–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Violi F, Cangemi R. Statin treatment as a confounding factor in human trials with vitamin E. J Nutr 2008; 138: 1179–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastori D, Polimeni L, Baratta F et al. The efficacy and safety of statins for the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Liver Dis 2014; 47: 4–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]