Abstract

The influenza pandemic of 1918 killed more than 50 million people. Why was 1918 such an outlier? I. W. Brewer, a US Army physician at Camp Humphreys, Virginia, during the First World War, investigated several factors suspected of increasing the risk of severe flu: length of service in the army, race, dirty dishes, flies, dust, crowding, and weather. Overcrowding stood out, increasing the risk of flu 10-fold and the risk of flu complicated with pneumonia five-fold. Calculations made with Brewer’s data show that the overall relationship between overcrowding and severe flu was highly significant (P < .001). Brewer’s findings suggest that man-made conditions increased the severity of the pandemic flu illness.

The global influenza pandemic of 1918–1919 killed more than 50 million people, orders of magnitude more deaths than other influenza epidemics.1–3 In its aftermath, there was tremendous interest in understanding why 1918 was such a deadly outlier; scientists published more than 4000 books and articles on flu in the decade following the pandemic.4–6 (“Flu” in this article designates the clinical illness. What we now call “influenza virus” was not isolated until the 1930s.) One of these articles involved an investigation conducted by I. W. Brewer, a physician who was stationed at Camp A. A. Humphreys in Virginia during the local peak of the pandemic, September 13 to October 18, 1918.7,8

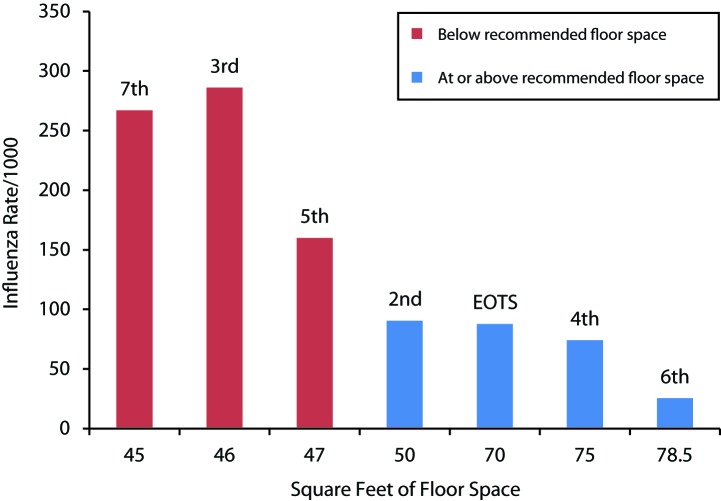

Brewer investigated several factors suspected of increasing the risk of severe flu: length of service in the army, race, dirty dishes, flies, dust, crowding, and weather. Among these factors, crowding stood out as having a strong correlation with disease incidence and severity. In one regiment with 78 square feet per soldier, 2.5% of the men fell ill with flu, whereas in another with only 45 square feet, 26.7% fell ill, a 10-fold difference (1 square foot is approximately equal to 0.1 m2). Limiting the analysis to severe cases of flu accompanied by pneumonia revealed that 1.4% and 6.9% of the soldiers in these two regiments, respectively, were afflicted, a five-fold difference. Using data from Brewer’s investigation, reproduced in Table 1 and Figure 1, one can determine that the relationship between crowding (less than 50 square feet per person) and flu, as well as the relationship between crowding and pneumonia, was highly significant (P < .001, χ2 statistic with Yates correction; GraphPad QuickCalcs 2015, GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

TABLE 1—

Number of Soldiers per Barracks, by Regiment, Square Feet of Floor Space per Soldier, and Influenza Incidence Rate per 1000 Soldiers: Camp A. A. Humphreys, Virginia, 1918

| Regiment | Number of Barracks | Number of Men per Barracks | Total Number of Men | Number of Square Feet of Floor Space | Influenza Rate per 1000 |

| 6th | 15 | 42 | 630 | 78.5 | 25.4 |

| 4th | 34 | 44 | 1496 | 75.0 | 74.0 |

| EOTS | 34 | 47 | 1598 | 70.0 | 87.7 |

| 2nd | 43 | 66 | 1978 | 50.0 | 90.5 |

| 5th | 49 | 70 | 3430 | 47.0 | 160.0 |

| 3rd | 42 | 72 | 3024 | 46.0 | 286.0 |

| 7th | 52 | 73 | 3796 | 45.0 | 267.0 |

Note. EOTS = Engineer Officers’ Training School.

FIGURE 1—

Flu Illness Incidence as a Function of Average Floor Space in Various Regiments During the Influenza Pandemic: Camp A. A. Humphreys, Virginia, 1918

Note. EOTS = Engineer Officers’ Training School. The sample size was n = 15 952. One square foot = 0.09 m2; 50 square feet = 4.65 m2.

At the time, 50 square feet was considered to be the minimum hygienic requirement for floor space in barracks. That standard dated to the 1860s, when US military leaders consulted with Florence Nightingale; she had proved in the Crimean War (1853–1856) that living conditions dramatically affected death rates among soldiers.9–13 Nevertheless, at Camp Humphreys, thousands of men were housed in overcrowded conditions. It was not until October 8, toward the end of the disaster, that the commanding general ordered a minimum of 50 square feet for each man.

The overcrowding at Camp Humphreys was typical of training camps across the country. The United States entered the First World War (1914–1918) in April 1917. Over the following year, America went from 100 000 men in uniform to about five million.14 This colossal mobilization produced hastily built facilities with overflowing barracks. Military physicians considered the crowding dangerous. Even before the pandemic, in January 1918, Army Surgeon General William Gorgas had testified in the Senate demanding more floor space for troops.15

Brewer’s contemporaries recognized the importance of his findings. For example, the postwar US Army Surgeon General’s report highlighted the article:

It would seem that the influence of [crowding] is best estimated by comparisons made between different organizations in the same camp whose surroundings are substantially the same and which show practically the same proportion of recruits. A study of this character was made at Camp Humphreys.16

The variation in floor space between units at Camp Humphreys created a natural experiment, one that “controlled” for factors such as climate and the timing of the epidemic. The increased severity of flu in the overcrowded units did not appear to have an explanation other than the overcrowding.

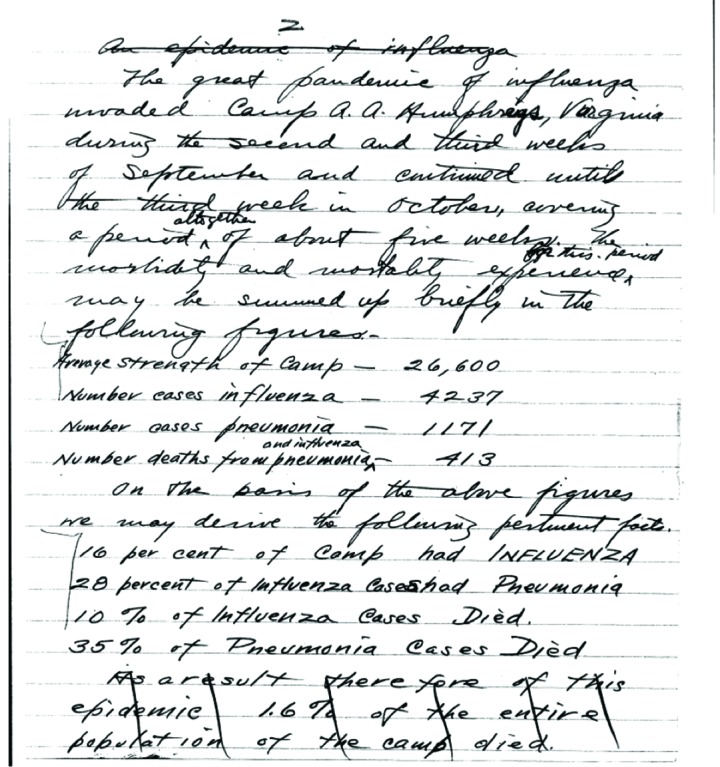

One of the potential difficulties in interpreting studies conducted in 1918 is the lack of specific laboratory testing for influenza. However, Brewer’s precision is helpful here. Brewer used quotation marks around the word influenza throughout his article to emphasize that no one knew what single germ was involved. Furthermore, as he pointed out, “ ‘influenza,’ uncomplicated, is not a cause of death.” In other words, those who died in the pandemic suffered from secondary cases of pneumonia as complications of flu. This observation is still widely accepted today; for example, a modern molecular study examining autopsy samples from 1918 confirmed that fatal 1918 flu cases all involved bacterial pneumonia.17 Thus, from a public health perspective, what mattered was identifying modifiable factors that increased the risk of severe disease, regardless of the microbe involved. Figure 2, a page of Brewer’s manuscript, reveals numbers that highlight these issues, as well as the devastation in the camp from the epidemic.

FIGURE 2—

Reproduction of Page 2 of Brewer’s Manuscript, Revealing Details About the Devastation in the Camp From the Epidemic

Source. Brewer.30

Although it was obvious that crowding helped spread respiratory infections such as flu, the import of Brewer’s study is that conditions of overcrowding in the army also appeared to increase the severity of the disease. Indeed, this was the consensus view at the time.18–22 Brewer’s article is also consistent with the theory that the deadly form of the 1918 flu, which eventually spread around the world, emerged among soldiers, specifically the US military.23–30

If war-related overcrowding was the key factor behind the 1918 flu’s extreme lethality, that would have profound implications. Knowledge of the specific etiology of infectious diseases is not necessary for preventing their deadly consequences. Further research into the host and environmental factors influencing the severity of the 1918 flu could be useful in understanding how to avoid the recurrence of similar catastrophes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Rebecca Royzer’s help with the preparation of the article is greatly appreciated. Thanks to the US National Archives and the online Influenza Encyclopedia – University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine for access to the Brewer manuscript.

ENDNOTES

- 1. Niall P. A. S. Johnson and Juergen Mueller. 2002. “Updating the Accounts: Global Mortality of the 1918–1920 ‘Spanish’ Influenza Pandemic.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 76: 105–115. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2. David K. Patterson. 1986. Pandemic Influenza: 1700–1900: A Study in Historical Epidemiology. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 91.

- 3. Niall Johnson. 2006. Britain and the 1918–19 Influenza Pandemic: A Dark Epilogue. New York, NY: Routledge, 65.

- 4. Alfred W. Crosby. 2003. America’s Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 323.

- 5. Ibid., 265.

- 6. Frank Burnet. 1968. Changing Patterns: An Atypical Autobiography. Melbourne, Victoria, Australia: Heinemann, 122.

- 7. I. W. Brewer. 1918. “Report of Epidemic of ‘Spanish Influenza’ Which Occurred at Camp A. A. Humphreys, VA., During September and October, 1918.” Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine 4 (3): 87–111.

- 8. Elizabeth Fee and Liping Bu. 2010. “Isaac Williams Brewer (1867–1928): An Unsung Hero.” American Journal of Public Health 100 (3): 423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9. William Hammond. 1863. A Treatise on Hygiene. Philadelphia, PA: J. B. Lippincott, 16.

- 10. Gillian Gill. 2005. Nightingales. New York, NY: Random House, 421.

- 11. Hammond, 325, 446.

- 12. Elizabeth Fee and Mary Garofalo. 2010. “Florence Nightingale and the Crimean War.” American Journal of Public Health 100 (9): 1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13. Gill, 418.

- 14. John Keegan. 2001. An Illustrated History of the First World War. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 330–333.

- 15. “General Gorgas Unheeded” [editorial], January 27, 1918, http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9E03EFD8143AEF33A25754C2A9679C946996D6CF (accessed February 2, 2016)

- 16. Milton Hall. 1928. “Inflammatory Diseases of the Respiratory Tract (Bronchitis, Influenza, Bronchopneumonia, Lobar Pneumonia),” http://history.amedd.army.mil/booksdocs/wwi/communicablediseases/chapter2.html (accessed February 2, 2016)

- 17. Zong-Mei Sheng, Daniel Chertow, Xavier Ambroggio, et al. 2011. “Autopsy Series of 68 Cases Dying Before and During the 1918 Influenza Pandemic Peak.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108 (39): 16416–16421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18. Edwin Oakes Jordan. 1927. Epidemic Influenza: A Survey. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association, 211.

- 19. Ibid., 475.

- 20. Ibid., 505.

- 21. Richard Hobday and John Cason. 2009. “The Open-Air Treatment of Pandemic Influenza.” American Journal of Public Health 99 (suppl. 2): S236–S242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22. Major Greenwood and Thomas Carnwath. 1920. “Report on the Pandemic of Influenza, 1918–19: Part II: Influenza in Great Britain and Ireland.” In: Reports on Public Health and Medical Subjects, No. 4, 190–191. London, UK: Ministry of Health, His Majesty’s Stationery Office.

- 23. Crosby, 56.

- 24. Jordan, 450.

- 25. Greenwood and Carnwath, 186–192.

- 26. Johnson, 49–50.

- 27. Niall P. A. S. Johnson. 2003. “The Overshadowed Killer: Influenza in Britain in 1918–19.” In New Perspectives, ed. Howard Phillips and David Killingray, 148. New York, NY: Routledge.

- 28. Maria-Isabel Porras-Gallo. 2014. “Between the Pandemic and World War I: The 1918–19 Influenza Pandemic in the Spanish Army, Through the Eyes of the Press.” In The Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918–1919: Perspectives from the Iberian Peninsula and the Americas, ed. Maria-Isabel Porras-Gallo and Ryan A. Davis, 103. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

- 29. Bruce Low. 1920. “The Incidence of Epidemic Influenza During 1918–19 in Europe and in the Western Hemisphere.” In Ministry of Health Reports on Public Health and Medical Subjects, No. 4. Report on the Pandemic of Influenza, 1918–19. Part III: Influenza in Foreign Countries, 215. London, UK: His Majesty’s Stationery Office.

- 30. I. W. Brewer. “Report of Epidemic of ‘Spanish Influenza’ Which Occurred at Camp A. A. Humphreys, VA., During September and October, 1918,” http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.6160flu.0014.616 (accessed February 2, 2016).