Abstract

Background

Recently, immunologic responses to localized irradiation are proposed as mediator of systemic effects after localized radiotherapy (called the abscopal effect). Here, we give an overview of both preclinical and clinical data about the abscopal effect in particular and link them with the immunogenic properties of radiotherapy.

Methods

We searched Medline and Embase with the search term “abscopal” from 1960 until July, 2014. Only papers that cover radiotherapy in an oncological setting were selected and only if no concurrent cytotoxic treatment was given. Targeted immune therapy was allowed.

Results

Twenty-three case reports, one retrospective study and 13 preclinical papers were selected. Eleven preclinical papers used a combination of immune modification and radiotherapy to achieve abscopal effects. Patient age range (28 to 83 years) and radiation dose (median total dose 32 Gy) varied. Fractionation size ranged from 1,2 Gy to 26 Gy. Time to documented abscopal response ranged between less than one and 24 months, with a median reported time of 5 months. Once an abscopal response was achieved, a median time of 13 months went by before disease progression occurred or the reported follow-up ended (range 3–39 months).

Conclusion

Preclinical data points heavily towards a strong synergy between radiotherapy and immune treatments. Recent case reports already illustrate that such a systemic effect of radiotherapy is possible when enhanced by targeted immune treatments. However, several issues concerning dosage, timing, patient selection and toxicity need to be resolved before the abscopal effect can become clinically relevant.

Keywords: irradiation, abscopal effect, radiotherapy, immune therapy

Introduction

Radiotherapy (RT) is highly effective anticancer treatment leading to local tumor control and potential cure for early stage cancer. Targeted ionizing irradiation has long been known to cause direct localized cell death. However, irradiation is also increasingly recognized to be able to induce tumor regression at non-irradiated, distant tumor sites. This phenomenon is called the “abscopal effect”, a term first introduced by Mole in 1953 and later on broadened by Andrews to include distant normal tissue effects [1, 2]. The existence of this type of effect is mainly described in sporadic case reports. Because documented abscopal regressions are rare, its clinical relevance is uncertain with current routinely used radiotherapy regimens. Nevertheless, recent insights regarding the immunogenic effects of RT and the biological mechanisms of the abscopal effect have provided renewed interest in the ability of radiotherapy to induce distant tumor regression leading to meaningful clinical benefit. The immune system has been proposed as the key component of abscopal effects after radiotherapy [3]. Local radiotherapy is known to induce an immunostimulatory form of cell death, called immunogenic cell death (ICD), leading to host immune responses [4–7]. The concept of ICD relies mainly on the release of damage associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) which trigger an antigen engulfment of dendritic cells (DC). This subsequently results in an improved antigen presentation to the cytotoxic immune system [8, 9] (see figure 1). Irradiation is also known to alter the immune phenotype of the tumor by augmenting the presence of MHC I on the tumor cell surface, improving expression of cancer-testis antigens and upregulating the FAS/CD95 complex [10–13]. Furthermore, RT is recognized to create a cytokine pattern that facilitates migration and function of effector CD8+ T cells [14, 15]. Therefore improved antigen expression and presentation as well as enhanced functioning of effector T cells provide a sound potential rationale for an immune mediated abscopal effect.

Figure 1. Immunogenic cell death.

Endoplasmatic reticulum stress induced by radiotherapy leads to apoptotic release of DAMPs such as ATP (find-me signal) and membrane blebs with the CRT/ERp57 complex (eat-me signal).

Here we overview the current state of knowledge of preclinical data and clinical experience regarding the abscopal effect. The aim of this review is to provide a systematic overview of the abscopal effect and identify links with the immunogenic properties of radiotherapy. Finally, we critically assess future therapeutic possibilities of radiotherapy in combination with the large number of emerging immunomodulatory agents [16].

Search strategy and selection criteria

References for this review were identified through searches of Medline and Embase with the broad search terms “abscopal”, “(non-targeted irradiation) OR (non-targeted radiotherapy)” and “distant bystander” from 1960 until July, 2014. Title and abstracts were screened by the main author and papers that were selected were verified by the other authors. English, Dutch and French clinical papers were included if they met the following criteria: patients had to receive single or multiple fractions of radiotherapy for any malignancy. Following radiotherapy, a non-irradiated tumor site needed to show size and/or metabolic regression. Biopsy confirmation of a responding distant site was not mandatory as clinical practice does not routinely require it. Papers were not considered eligible if whole body irradiation was used or if concurrent systemic treatment with a cytotoxic drug was given. Sequential cytotoxic treatment after radiotherapy was not allowed unless an abscopal radiotherapy response was assessed before the following systemic treatment was given. Concurrent or sequential immune modifying therapy was included though handled separately from radiotherapy-only cases.

For preclinical research relevant to an abscopal effect, the final reference list needed to focus on abscopal effects in the oncological setting. Therefore, only in vivo studies that concerned a malignancy were selected as in vitro models are mostly confined to study short-range bystander effects. Distant tumor regression was an essential endpoint. Combinations of immune modifying agents and radiotherapy were included. Concurrent treatment with a cytotoxic drug was not allowed.

References of selected clinical and preclinical papers were also screened for additional papers that met our selection criteria.

Results

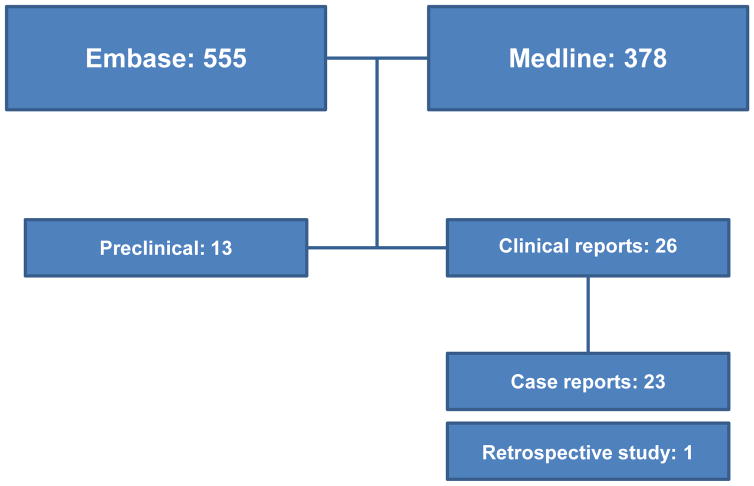

Using the described methodology, we identified 378 Medline and 555 Embase references in total (figure 2). Thirteen preclinical papers were retrieved that directly identified abscopal effects in vivo, which are summarized in table 1. Eleven of these studies used radiotherapy in conjunction with an immune treatment to achieve an abscopal effect. Out of the 5 different mouse models, BALB/C and C57BL/6 were by far the most used (6 times each). Dose varied extensively, ranging from one fraction of 2 Gy to 3–5 fractions of 10 Gy and even high dose single fractions of 60 Gy.

Figure 2. Search results.

Breakdown of the number of papers identified according to the search strategy and selection criteria.

Table 1.

Overview of preclinical studies according to the search criteria.

| Pub. Year | Ref. | Tumor type | Irradiated site/Dose | Immune therapy | Observed abscopal effect | Suggested mediator |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | [26] | TUBO mammary/MCA38 colon | Flank/12 Gy | Anti-PD-L1 | Distant tumor growth inhibition | CD8-lymphocytes |

| 2014 | [48] | FM3A mammary | Flank/6 Gy | ECI301 | Distant tumor growth inhibition | HMGB1 |

| 2014 | [38] | HCT116 colon | Flank/10–20 Gy | None | Distant tumor growth inhibition | p53 |

| 2011 | [22] | Colon26 | Flank/20 Gy | IL-2 | Decreased no of hepatic M+ | CD4-lymphocytes |

| 2009 | [49] | TSA mammary/MCA38 colon | Flank/20-24-30 Gy | 9H10 | Distant tumor growth inhibition | unknown |

| 2008 | [23] | Colon26/MethA sarcoma/LLC | Flank/6 Gy | ECI301 | Distant tumor growth inhibition | CD4+/CD8+/NK-cells |

| 2007 | [50] | SCC VII | Femur/4–10 Gy | DC | Distant tumor growth inhibition | DC/gp96 |

| 2005 | [24] | 4T1 mammary | Flank/12–24 Gy | 9H10 | Distant tumor growth inhibition | CD8-lymphocytes |

| 2004 | [21] | 67NR mammary | Flank/2–6 Gy | Flt3-L | Distant tumor growth inhibition | DC/T cells |

| 2003 | [39] | LCC/T241 fibrosarcoma | Hind leg/24–50 Gy | None | Distant tumor growth inhibition | p53 |

| 2003 | [51] | D5 melanoma/MCA 205 sarcoma MethA | Flank/42,5 Gy | DC | Distant tumor growth inhibition | DC |

| 2001 | [52] | C3 cervical/sarcoma | Hind leg/30–50 Gy | DC | Distant tumor growth inhibition | DC |

| 1999 | [19] | LCC | Foot/60 Gy | Flt3-L | Lung M+ regression | DC |

M+ = metastasis. LCC = Lewis Lung Carcinoma, DC = dendritic cells, SCC = squamous cell carcinoma.

One retrospective clinical study was retrieved. No randomized clinical studies were identified. A total of 25 case reports were initially eligible, all based on one or more clinical cases, but two of those case reports which described 12 individual clinical cases were additionally rejected due to insufficient clinical information [17, 18]. Thus, we ultimately retrieved 23 case reports of a perceived abscopal effect through radiation therapy with or without immune therapy. These are summarized in table 2 and 3 respectively. Patient age ranged from 28 to 83 years, with a median age of 64,5. Interestingly, renal cell carcinoma was the most frequent histology in the group without immune therapy, with 7 cases, followed by 4 cases of hepatocellular carcinoma. Radiation doses varied as well, with a median total dose of 32 Gy (range 12 Gy – 60,75 Gy). Fractionation size ranged from 1,2 Gy to 26 Gy. Eight cases were irradiated on the primary tumor site, 14 on a distant metastatic or nodal site. Time to documented abscopal response ranged between less than one and 24 months, with a median reported time of 5 months. Once an abscopal response was achieved, a median time of 13 months went by before disease progression occurred or the reported follow-up ended (range 3–39 months). In 11 case reports the progressive free survival time could not be assessed.

Table 2.

Clinical cases of abscopal effect after RT according to the search criteria.

| Pub. Year |

Ref. | ♂ ♀ |

Age | Histology | Primary site | Treatment of primary |

RT treated sites | RT Dose/ Fractions |

Non-irradiated abscopal regression |

Time to abscopal response |

PFS after response* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | [53] | F | 78 | Adenocarcinoma | Lung | SRT | Primary | 26 Gy/1x | Bone M+ Adrenal M+ |

12 m | 3 m |

| 2012 | [54] | M | 61 | RCC | Kidney | Nephrectomy | Brain M+ Bone M+ |

18 Gy/1x 40 Gy/8x |

Lung M+ Bone M+ |

1 m | 33 m |

| 2012 | [55] | M | 72 | Medullary carcinoma | Thyroid | Thyroidectomy | LN 4R (mediastinal) | 30 Gy/3x | LN 6 (mediastinal) | 1m | NR |

| 2011 | [56] | M | 63 | HCC | Liver | Hepatic Lobectomy | Mediastinal LN | 60,75 Gy/27x | Lung M+ | 1 m | 36 m |

| 2011 | [57] | M | 70 | Merkel cell carcinoma | Calf | Excision + adjuvant EBRT | In-transit cutaneous M+ | 12 Gy/2x | Other cutaneous M+ | ≤ 1 m | 25 m |

| 2009 | [58] | F | 65 | Lymphocytic leukemia | Axillar LN | CT (PD) | Axillar LN | 24 Gy/12x | Cervical LN | ≤ 1 m | 6 m |

| 2008 | [43] | M | 79 | HCC ** | Liver | Embolization one lesion | VCI invasive lesion | 48 Gy/NR | Hepatic sites | 5 m | NR |

| 2007 | [59] | F | 69 | SCC | Cervix | EBRT Brachytherapy | Primary tumor | 50,8 Gy/27x 24 Gy/4x |

Para-aortic LN | NR | NR |

| 2006 | [60] | F | 83 | RCC ** | Kidney | SRT | Primary tumor | 32 Gy/4x | Lung M+ Abdominal LN |

24 m | NR |

| 2006 | [60] | F | 64 | RCC | Kidney | Nephrectomy | Lung M+ | NR | Lung M+ | 5 m | NR |

| 2006 | [60] | M | 69 | RCC | Kidney | Nephrectomy | Lung M+ | 30 Gy/2x | Lung M+ | 3 m | 8 m |

| 2006 | [60] | F | 55 | RCC | Kidney | SRT | Primary tumor | 32 Gy/4x | Abdominal LN+ | 5 m | NR |

| 2005 | [61] | M | 65 | HCC | Liver | None | Bone M+ | 30 Gy/NR | Hepatic sites Bone M+ |

10 m | 13 m |

| 1998 | [41] | M | 76 | HCC | Liver | Resection/Embolization/CT (PD) | Bone M+ | 36 Gy/NR | Hepatic sites Bone M+ |

10 m | 29 m |

| 1995 | [62] | M | 77 | CLL | / | CT (PD) | Neck/supraclavicular LN | 32,4 Gy/NR | Peripheral LC Splenomegaly |

≤ 1 m | NR |

| 1994 | [63] | M | 58 | RCC | Kidney | EBRT | Primary tumor | 20 Gy/10x | Lung M+ Mediastinal LN |

6 m | 11 m |

| 1983 | [64] | M | 49 | Adenocarcinoma | Oesophagus | EBRT | Primary tumor | 40 Gy/20x | Lung M+ | 6 m | 13 m |

| 1983 | [64] | M | 56 | Adenocarcinoma | Lung | EBRT | Primary tumor | 35 Gy/10x | Cutaneous M+ | ≤ 1 m | 6 m |

| 1981 | [65] | F | 73 | RCC | Kidney | Nephrectomy | Groin M+ | 40 Gy/15x | Lung M+ | ≤ 12 m | 39 m |

| 1977 | [66] | M | 44 | Lymphocytic lymphoma | LN | EBRT | Mantle field | 30 Gy/20x | Abdominal LN | ≤ 1 m | NR |

| 1977 | [66] | M | 40 | Lymphocytic lymphoma | LN | EBRT | Mantle field | 30 Gy/20x | Abdominal LN | ≤ 1 m | NR |

| 1975 | [67] | M | 28 | Melanoma | Knee | Wide excision | Right inguinal LN | 14,4 Gy/12x | Para-aortic LN | 2 m | 17 m |

| 1973 | [68] | F | 35 | Adenocarcinoma | CUP | / | Neck/Supra-clavicular LN | 40 Gy/20x | Mediastinal mass | NR | NR |

PFS = progressive free survival, M = male, F = Female, EBRT = external beam radiotherapy, CT = chemotherapy, RCC = renal cell carcinoma, M+ = metastasis, HCC = hepatocellular carcinoma, LN = lymph node(s), PD = progressive disease, VCI = vena cava inferior, SCC = squamous cell carcinoma, SRT = stereotactic radiation therapy, CLL= chronic lymphocytic leukemia, LC = lymphocytes, CUP = cancer of unknown primary, NR = not reported, / = not applicable.

This indicates the time period that went by from the observation of abscopal regression until progressive disease OR until reported follow-up ended.

No pathological diagnosis was reported. Tentative diagnosis based on imaging and disease presentation.

Table 3.

Clinical cases of abscopal effect after RT + immune therapy.

| Pub. Year | Ref. | ♂ ♀ |

Age | Histology | Primary site | Treatment of primary | RT treated sites | Treatment + RT Dose/fractions | Non-irradiated abscopal regression | Time until abscopal response | PFS after response* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | [69] | M | 74 | Adenocarcinoma | Lung | Resection | Supraclavicular LN | BCG-vaccine 58 Gy/29x |

Lung M+ | 6 m | 47 m |

| 2013 | [33] | M | 64 | Adenocarcinoma | Lung | CT (PD) | Hepatic M+ | Ipilimumab 30 Gy/5x |

Liver M+/Bone M+/Lung M+ | 3 m | 5 m |

| 2012 | [34] | M | 57 | Melanoma | Arm | Wide excision/axillary dissection | Hepatic M+ | Ipilimumab 54Gy/3x |

Cutaneous M+ | 6 m | 6 m |

| 2012 | [36] | M | 67 | Melanoma | Scalp | CT (PD) | Brain M+ | Ipilimumab SRT** |

Nodal M+ | NR | NR |

| 2012 | [35] | F | 33 | Melanoma | Upper back | Wide excision | Paraspinal M+ | Ipilimumab 28,5 Gy/3x |

Splenic M+/hilar LN | 4 m | 6 m |

PFS = progressive free survival, M = male, F = Female, M+ = metastasis, LN = lymph node(s), EBRT = external beam radiotherapy, CT = chemotherapy, PD = progressive disease, SRT = stereotactic radiation therapy.

This indicates the time period that went by from the observation of abscopal regression until progressive disease OR until reported follow-up ended.

Total dose and fractionation not reported.

Discussion

The effector T cell response is crucial for abscopal effects

Preclinical studies investigating the abscopal effect are relatively immature. As one of the first to demonstrate an abscopal effect in vivo, Chakravarty et al. set up a metastatic Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) model in the feet of mice and irradiated only one tumor localization with a single dose of 60 Gy. Subsequently, this group administered Fms-like tyrosine kinase receptor 3 ligand (Flt3-L), a growth factor for dendritic cells (DC)[19]. Combination treatment improved disease-free survival at 20 weeks by 56% and reduced non-irradiated pulmonary metastasis (evaluated by mean lung weight) on multiple sites compared to monotherapy of either RT or Flt3-L. The addition of improved dendritic cell growth to the enhanced antigen processing and presentation of RT lead to a systemic response in this setting. Additionally, the abscopal effect was lost in athymic mice, indicating the potential importance of T cell presence in the host. In a follow-up study, increased levels of IL-12, IFN-γ and IL-2 also point to a pro cytotoxic T cell pattern as the driver behind systemic tumor regression [20]. This synergy between RT and Flt3-L and the importance of proper T cell functioning was confirmed in a poorly immunogenic mammary carcinoma model (67NR) by Demaria et al. [21].

Furthermore, Yasuda et al. used IL-2 injections to successfully reach an abscopal effect [22]. IL-2 - already described as an important driver for an abscopal effect by Chakravarty et al. - is a stimulator of effector T cells and was administered after irradiating an established subcutaneous colon26 tumor (10x 2 Gy). Thus, a systemic response was achieved not by increasing antigen presentation through DC manipulation, but by enhancing the function of the T cells in a more direct manner. Shiraishi et al. used ECI301, a macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (MIP-1α) variant, as a tool to create a more tumoricide environment [23]. MIP-1α is secreted by various leukocytes and recruits monocytes, dendritic cells, NK cells and T cells. Only combination treatment showed a reduction in tumor growth at the non-irradiated side. Irradiation of the normal tissue in the hind flank in combination with ECI301 did not elicit an abscopal effect. When looking at T cell infiltration, irradiation with ECI301 caused increased CD4+ and CD8+ populations in both irradiated and non-irradiated tumors. This was not observed with ECI301 or RT alone and depletion of these cell populations abrogated the abscopal effect completely. Although most of these drugs did not impact standard clinical treatments, they do illustrate that the synergy between radiotherapy and immune treatment enables a strong systemic effect. This systemic effect relies upon a broad T cell foundation, inclusive of a functional system ranging from antigen presentation to effector T cell response. The multitude of experimental drugs that are capable of enhancing such a T cell response indicates a lot of potential to unlock consistent abscopal effects in clinical practice.

Targeted immune therapy opens the door for synergistic combination treatments

In recent years, the emergence of immunotherapies in a clinical setting is opening up new opportunities to elicit abscopal effects. Demaria et al. illustrated this potential with an experiment that combined cytotoxic lymphocyte antigen-4 blockade (CTLA-4) with irradiation [24]. Combination treatment of RT and CTLA-4 blockade did result in a significant survival improvement over the monotherapy and control groups. CTLA-4 is a checkpoint mechanism that regulates the immune system and prevents overstimulation and resultant autoimmunity. CTLA-4 is a key molecule for regulatory T cells in this regard. CTLA-4 blockade is widely accepted as an effective approach in malignant melanoma and is a prime candidate for other cancer treatments as well [25]. This correlated with the impairment of lung metastases formation as an abscopal effect. Through depletion experiments they also displayed that the presence of CD8+ T cells was crucial in obtaining such a result.

Deng et al. investigated the role of potential synergistic RT-immunotherapy regimens to anti-PD-L1 [26]. PD-L1 (programmed death-ligand 1) is an important player in inhibiting a proficient T cell response. Asides from an increase in PD-L1 expression in the tumor microenvironment after a single dose of 12 Gy, they showed a growth reduction at the non-irradiated site when combination therapy was administered.

In summary these in vivo studies emphasize the rarity of abscopal effects in the setting radiotherapy alone without additional immunomodulation, in keeping with the published clinical case reports. In contrast, the preclinical data provide encouraging results for a variety of immunomodulatory agents which may synergize with radiotherapy to induce durable systemic anti-tumor immune responses, providing support to translate such findings to the clinic.

Frequency of clinical abscopal effects is dependent on tumor type and follow-up

Clinical cases of abscopal effects in response to radiotherapy have been reported since 1973. Nevertheless, there have only been a limited number of clear-cut systemic responses identified in the last forty years. Preclinical research also fails to consistently reproduce abscopal effect by RT alone. Nevertheless, the clinical case reports illustrate a number of important aspects that might influence the presence of these abscopal effects. When reviewing the case reports, an immediate observation is the striking feature of the abscopal effects occurring in immunologically prominent tumor types such as RCC, melanoma and HCC. In this context, it is remarkable that these are frequently associated with spontaneous regression as well [27]. One could argue that the abscopal effect actually is a coincidental representation of spontaneous regression. The inflammatory microenvironment and the cytotoxic immune system have been suggested as the main drivers of spontaneous regression [28–30]. However, the aforementioned preclinical data shows a strong T cell dependence in response to inflammatory radiation stimulus when documenting abscopal effects as well. Thus, it is not surprising that abscopal effects as well as spontaneous regression are more prevalent in two tumor types that are recognized for having a more established immunogenicity. Distinguishing abscopal effects from spontaneous regression is not straightforward, which might lead to underreporting.

Recognizing true abscopal effects is particularly challenging in the setting of a hematological malignancy. It is reported that circulating neoplastic lymphocytes that pass through the irradiated field could account for gradual cell depletion/death of the total circulating lymphocyte pool and mimic an abscopal effect due to lymph node reduction [31]. Identification of the abscopal effect is limited by the scheduled restaging imaging too. Both the restaging method and its timing impact the perceived presence and extent of an abscopal effect. Some case reports describe solely clinical regression or only performed partial disease imaging. Moreover, after palliative radiotherapy, there is often a loss of follow-up or second or third line systemic treatment is immediately started. This masks potential distant disease regression due to an adaptive immune response. To completely assess abscopal effects a full picture of the disease evolution should be made on regular time intervals while recognizing confounders such as sequential chemotherapy.

The difference in immunogenic potential between tumor types and probably between individuals should be taken into account when developing trials that study the immunogenic potential of radiotherapy. Although abscopal effects are more often missed rather than recognized due to the aforementioned reasons, it still remains a rare phenomenon. To apply irradiation in an immunogenic setting, additional therapeutics need to be considered.

Abscopal effects after clinical combination treatments

The immunologic potential of certain tumors also comes forward in the multiple case reports that describe combination treatment of RT and immunotherapy. A number of manuscripts have confirmed the presence of an abscopal effect of radiotherapy in combination with an immunomodulating agent. Four case reports with ipilimumab and one with BCG-vaccination are summarized in table 3. Only one retrospective study was performed, about the sequence ipilimumab-radiotherapy in 21 patients with melanoma [32]. They were considered eligible when they showed progressive disease after ipilimumab (3-weekly, 3 mg/kg) and received palliative radiotherapy afterwards. Eleven patients (52%) showed an abscopal response after RT, two of which had stable disease for >3 months instead of a distant partial or complete response. Time to abscopal response ranged from 1 to 4 months. Median overall survival increased to 13 months, which differed significantly from the patients without an abscopal response. Although retrospective, this data really complements the findings of the case reports. Not surprisingly, malignant melanoma was chosen to investigate as it is one of the cancers that act on the forefront of immunotherapy studies. Response time is typically several months after irradiation, which fits with a cellular immune response. An important aspect of this study is that it consisted of sequential therapy rather than concurrent. Concurrent success is illustrated by Golden et al., who administered 4 three-weekly cycles of ipilimumab (3mg/kg) for lung adenocarcinoma [33]. The first cycle was initiated one day after starting the radiotherapy schedule (6 fractions of 5Gy). Hiniker et al. also prospectively combined stereotactic radiotherapy (54 Gy in 3 fractions) with ipilimumab, this time in a metastatic melanoma patient [34]. Postow et al. reported that their patient received 4 cycles of induction ipilimumab (10mg/kg) for malignant melanoma after which maintenance treatment was started twelve-weekly (dose not specified)[35]. After more than one year of maintenance treatment with slightly progressive disease, palliative radiotherapy was started (28,5 Gy in 3 fractions). One month later one more cycle of ipilimumab was given which resulted in a subsequent abscopal response. Stamell et al. reported an abscopal effect after combining ipilimumab with stereotactic radiotherapy in a melanoma patient [36].

Ipilimumab is currently the most used immune agent available. It causes CTLA-4 blockade which leads to a decreased regulatory T cell activity. It synergizes well with RT since regulatory T cells lead to a suppressed immune response and tend to be more radioresistant than other T cells [37]. Both preclinical data and clinical case reports strongly hint towards CTLA-4 blockade as a prime candidate for combination treatments. However, the wide array of successfully applied drugs in preclinical models also suggests a broad synergistic potential of other drugs. Promising clinical immune agents like PD-1/PD-L1 blockade should therefore be explored in combination with radiotherapy as well.

In sequential therapy, it may be challenging to delineate the abscopal contribution from radiation therapy with delayed immunotherapeutic response. When concurrent RT and immune therapy is applied, it is impossible to distinguish an abscopal effect from a pure drug effect. To make a qualitative assessment of relative contributions of effect, biomarkers for an RT induced immune response are much needed. Assessing the scale of the abscopal effect when combined with immune therapy is beyond the scope of the present review. Future clinical trials with rigorous investigation of sequence and timing of radiotherapy and immunotherapy combinations are best placed to determine the relative activity of each treatment modality.

Unraveling molecular mechanisms

Although hard endpoints are to be prioritized when evaluating abscopal responses, the importance of the underlying molecular mechanisms should not be underestimated. Knowledge of significantly related circulating proteins is vital for the development of biomarkers and potentially able to open up new therapeutic approaches. With the exception of immunogenic cell death, this is still largely unexplored terrain. Two preclinical models suggest p53 as a key mediator for abscopal effects [38, 39]. In clinical research, a couple of the mentioned papers also explored individual markers in abscopal responses. Postow et al. explored the presence of NY-ESO-1 antibodies after radiotherapy. NY-ESO-1 is a prime example of a cancer-testis antigen and a high antibody titer increases the efficiency of ipilimumab [40]. That titer turned out to be 30 times higher after radiotherapy than before. Additionally, they also observed a supplemental increase of CD4+ T cells after RT, and a decrease in myeloid-derived suppressor cells right before an abscopal regression was identified. Titers against melanoma antigen-A3 rose significantly after irradiation and ipilimumab as well.

A more cytokine focused approach was used by Ohba et al. In a patient with metastasized hepatocellular carcinoma, they performed serial measurements of serum cytokines before and after radiotherapy [41]. An abscopal regression occurred together with a decrease in AFP. More importantly, they also displayed an increase of TNF-α after RT. TNF-α is capable of inducing cell death and activate natural killer cells and thus applied in several experimental regimens as a cancer treatment [42]. In contrast, Nakanishi et al. performed the same cytokine panel, also in a patient with HCC, but without a notable increase in TNF-α [43]. They did note a rise in IL-18 both before and after radiotherapy.

The current occasional explorative testing for molecular mechanisms is able to suggest, but not to conclude. Implementing a thorough molecular approach in clinical trials is important for biomarker development and obtaining more insight in the molecular pathways that form the foundation of an adaptive antitumor immune response.

Time & dose are of the essence

Since an abscopal response is dependent on cytotoxic immunity, it is expected that several weeks to months need to pass before an adequate assessment can be made. The clinical data suggests that indeed a time frame of several months is needed before a clinical response can be detected. As an indirect indicator of an adaptive immune response, there is a notable similarity with ipilimumab. It is suggested that clinicians should not terminate treatment with ipilimumab prematurely since there is an important variance in time to response [44]. Once disease progression is halted, it usually can maintain this state for a very long time, which the case reports of abscopal effect indicate as well. A cytotoxic T cell based anti-tumor effect fits this pattern perfectly. A closely related aspect is the close timing of radiotherapy and immune modifying agents in preclinical mouse work. The theoretical concept of ICD and improved immunogenicity through irradiation supports the concept that a concurrent administration of radiotherapy and immune modifying agents is superior to sequential treatments. The preclinical work indicates that separating RT and immune modification in time reduces the therapeutic efficacy. This should be confirmed clinically. But even then, a lot of questions remain. Is this a one-shot treatment or does repeated exposition to irradiation throughout immunotherapy bring additional benefit? Such a repeated approach could be thought of as booster treatments, in analogy with vaccination schedules. On top of that, if systemic immunity needs a median of 4 months to attend a beneficial effect, it might be opportune to continue immune treatments for at least 4–6 months.

Closely related to the timing of both therapy components is the irradiation schedule that is applied. Most preclinical data today uses high dose, low fractionated radiotherapy, although this is only holds limited clinical appeal. The importance of RT scheduling is also hinted at by Dovedi et al. They showed that the combination of RT and anti-PD-L1 may overcome RT induced adaptive resistance by upregulation of PD-L1 [45]. This upregulation of PD-L1 occurs with fractionated RT. The article illustrates that incorporating radiobiological differences of varying fractionation and dose is crucial to keep a translational perspective. Efficacy of drug-RT combinations can change when dose and fractionation change.

Limits of current study design

There are several limitations to the current clinical and preclinical data that need to be pointed out. Radiographic evaluation was often not described well in the case reports. A one-dimensional and/or volumetric response assessment is implied in most case reports, but often without any detailed information regarding effect size. Additionally, the time point and method of tumor assessment are often arbitrary, which is an important facet since they often determine the ‘appearance’ and validity of an abscopal effect. Another important issue is the translational validity of preclinical mouse work. Tumor immune phenotype is extremely important and highly variable in a clinical setting, which begs the question if strict mouse models represent suitable circumstances for an abscopal effect based on irradiation alone. Moreover, the number of preclinical studies is limited and varies in set-up and methodology. This can definitely be extended towards parameters like total dose, dose fractionation and timing as discussed. If substantial progress is to be made, they need to be addressed.

Horizon scanning and future challenges

Irradiation should be regarded as an immunogenic hub to induce an in situ vaccination on which immunomodulatory agents can enhance systemic immune response. Conversely, many issues need to be addressed before radiotherapy can become such a valid immunogenic tool. Initiating clinical trials right now might yield success, but it also has the pitfall of quickly writing off a new therapeutic strategy because of poor study set-up. First and foremost, thorough knowledge about the relation between dose/fractionation and the immune effects of radiation is required. Preclinical and clinical work need to implement comparative regimens to establish optimal RT parameters. Changes in the structural tumor microenvironment that occur with different RT doses need to be taken into account. One example is the vascular disruption that occurs when ablative radiotherapy is given, which could alter drug delivery [46]. Additionally, timing of immune therapy with radiotherapy is crucial. It is probable that there is a window of opportunity that leads to an optimal synergy between RT and immune agents, which needs to be explored and defined. However, true concurrent regimens are not often applied in clinical trials because of fear of increased toxicity, which keeps preclinical work from reaching proper clinical implementation. The presumed increase in adverse effects when using concurrent radio– and immunotherapy has been doubted by a recent review by Barker et al. [47]. Further data on the safety of combining immune agents and radiotherapy is required.

Another area of increasing importance will be the development of suitable biomarkers that will be able to reliably assess ‘immunogenic tumor cell death’, immune effector stimulation and adaptive immunity. Such an immune profile of biomarkers will aid in searching for an optimal combination of radiotherapy and immunomodulation and allows for patient selection and response prediction. Preclinical models, although sometimes lacking in translational potential still form an important asset in guiding biomarker research.

Conclusion

In this review we conclude that an irradiation induced abscopal effect is based on antitumor immunity. Abscopal effects were observed at all ages, across a variety of tumor types and with substantial differences in radiotherapy regimens and techniques. However, they do seem to occur more in known immunogenic tumor types. At the same time, the rarity of documented reports and the preclinical research suggest that abscopal effects induced by RT alone are unlikely to have major clinical impact on disease control in the context of metastatic disease. Preclinical data suggests that immune therapy synergizes with radiotherapy to enhance adaptive antitumor immunity and allow for systemic effects after irradiation, but attention needs to be given towards optimizing of dose regimens and timing, as well as patient selection through biomarkers. These are necessary steps to unlock a more efficient long term immune response after radiotherapy and make the abscopal effect clinically relevant.

Highlights.

Current clinical and preclinical data of the abscopal effect is summarized.

The abscopal effect is linked with the immunogenic properties of irradiation.

Radiotherapy has a potential synergy with immune agents.

The issues that come with combining radiotherapy and immune agents are addressed.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments/Funding:

This research was funded by the Flemish League against Cancer (Vlaamse Liga tegen Kanker, VLK) and a grant for Diverse Research Actions (Diverse Onderzoeksacties, DOA) of the Special Research Fund from KU Leuven.

Footnotes

- Kobe Reynders: conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article

- Tim Illidge: interpretation of data, revising the article critically for important intellectual content

- Shankar Siva: interpretation of data, revising the article critically for important intellectual content

- Joe Y. Chang: interpretation of data, revising the article critically for important intellectual content

- Dirk De Ruysscher: interpretation of data, revising the article critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be submitted

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mole R. Whole body irradiation therapy - radiobiology or medicine? Br J Radiol. 1953:234–41. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-26-305-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrews JR. Radiobiology of Human Cancer Radiotherapy. 1978 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Formenti SC, Demaria S. Systemic effects of local radiotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(7):718–26. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70082-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Apetoh L, Ghiringhelli F, Tesniere A, Obeid M, Ortiz C, Criollo A, et al. Toll-like receptor 4-dependent contribution of the immune system to anticancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Nat Med. 2007;13(9):1050–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Obeid M, Panaretakis T, Joza N, Tufi R, Tesniere A, van Endert P, et al. Calreticulin exposure is required for the immunogenicity of gamma-irradiation and UVC light-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14(10):1848–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perez CA, Fu A, Onishko H, Hallahan DE, Geng L. Radiation induces an antitumour immune response to mouse melanoma. Int J Radiat Biol. 2009;85(12):1126–36. doi: 10.3109/09553000903242099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gameiro SR, Jammeh ML, Wattenberg MM, Tsang KY, Ferrone S, Hodge JW. Radiation-induced immunogenic modulation of tumor enhances antigen processing and calreticulin exposure, resulting in enhanced T-cell killing. Oncotarget. 2014;5(2):403–16. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krysko DV, Garg AD, Kaczmarek A, Krysko O, Agostinis P, Vandenabeele P. Immunogenic cell death and DAMPs in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(12):860–75. doi: 10.1038/nrc3380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kroemer G, Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Zitvogel L. Immunogenic cell death in cancer therapy. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31:51–72. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-100008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reits EA, Hodge JW, Herberts CA, Groothuis TA, Chakraborty M, Wansley EK, et al. Radiation modulates the peptide repertoire, enhances MHC class I expression, and induces successful antitumor immunotherapy. J Exp Med. 2006;203(5):1259–71. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma A, Bode B, Wenger RH, Lehmann K, Sartori AA, Moch H, et al. gamma-Radiation promotes immunological recognition of cancer cells through increased expression of cancer-testis antigens in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e28217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Golden EB, Pellicciotta I, Demaria S, Barcellos-Hoff MH, Formenti SC. The convergence of radiation and immunogenic cell death signaling pathways. Front Oncol. 2012;2:88. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chakraborty M, Abrams SI, Camphausen K, Liu K, Scott T, Coleman CN, et al. Irradiation of tumor cells up-regulates Fas and enhances CTL lytic activity and CTL adoptive immunotherapy. J Immunol. 2003;170(12):6338–47. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.12.6338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burnette BC, Liang H, Lee Y, Chlewicki L, Khodarev NN, Weichselbaum RR, et al. The efficacy of radiotherapy relies upon induction of type i interferon-dependent innate and adaptive immunity. Cancer Res. 2011;71(7):2488–96. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lim JY, Gerber SA, Murphy SP, Lord EM. Type I interferons induced by radiation therapy mediate recruitment and effector function of CD8(+) T cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2014;63(3):259–71. doi: 10.1007/s00262-013-1506-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vacchelli E, Vitale I, Tartour E, Eggermont A, Sautes-Fridman C, Galon J, et al. Trial Watch: Anticancer radioimmunotherapy. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2(9):e25595. doi: 10.4161/onci.25595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rees GJ. Abscopal regression in lymphoma: a mechanism in common with total body irradiation? Clin Radiol. 1981;32(4):475–80. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(81)80310-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prithviraj G, Peter O, Lisa A. Abscopal effect and carcinomatous myelopathy: A case report. Neuro Oncol. 2012;14(Suppl 6):133–41. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chakravarty PK, Alfieri A, Thomas EK, Beri V, Tanaka KE, Vikram B, et al. Flt3-ligand administration after radiation therapy prolongs survival in a murine model of metastatic lung cancer. Cancer Res. 1999;59(24):6028–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chakravarty PK, Guha C, Alfieri A, Beri V, Niazova Z, Deb NJ, et al. Flt3L therapy following localized tumor irradiation generates long-term protective immune response in metastatic lung cancer: its implication in designing a vaccination strategy. Oncology. 2006;70(4):245–54. doi: 10.1159/000096288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Demaria S, Ng B, Devitt ML, Babb JS, Kawashima N, Liebes L, et al. Ionizing radiation inhibition of distant untreated tumors (abscopal effect) is immune mediated. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58(3):862–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yasuda K, Nirei T, Tsuno NH, Nagawa H, Kitayama J. Intratumoral injection of interleukin-2 augments the local and abscopal effects of radiotherapy in murine rectal cancer. Cancer Sci. 2011;102(7):1257–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.01940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shiraishi K, Ishiwata Y, Nakagawa K, Yokochi S, Taruki C, Akuta T, et al. Enhancement of antitumor radiation efficacy and consistent induction of the abscopal effect in mice by ECI301, an active variant of macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(4):1159–66. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Demaria S, Kawashima N, Yang AM, Devitt ML, Babb JS, Allison JP, et al. Immune-mediated inhibition of metastases after treatment with local radiation and CTLA-4 blockade in a mouse model of breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(2):728–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDermott D, Lebbe C, Hodi FS, Maio M, Weber JS, Wolchok JD, et al. Durable benefit and the potential for long-term survival with immunotherapy in advanced melanoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40(9):1056–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2014.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deng L, Liang H, Burnette B, Beckett M, Darga T, Weichselbaum RR, et al. Irradiation and anti-PD-L1 treatment synergistically promote antitumor immunity in mice. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(2):687–95. doi: 10.1172/JCI67313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar T, Patel N, Talwar A. Spontaneous regression of thoracic malignancies. Respir Med. 2010;104(10):1543–50. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin TJ, Liao LY, Lin CL, Shih LS, Chang TA, Tu HY, et al. Spontaneous regression of hepatocellular carcinoma: a case report and literature review. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51(56):579–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huz JI, Melis M, Sarpel U. Spontaneous regression of hepatocellular carcinoma is most often associated with tumour hypoxia or a systemic inflammatory response. HPB (Oxford) 2012;14(8):500–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2012.00478.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ricci SB, Cerchiari U. Spontaneous regression of malignant tumors: Importance of the immune system and other factors (Review) Oncol Lett. 2010;1(6):941–45. doi: 10.3892/ol.2010.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nobler MP. The abscopal effect in malignant lymphoma and its relationship to lymphocyte circulation. Radiology. 1969;93(2):410–2. doi: 10.1148/93.2.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grimaldi AM, Simeone E, Giannarelli D, Muto P, Falivene S, Borzillo V, et al. Abscopal effects of radiotherapy on advanced melanoma patients who progressed after ipilimumab immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology. 2014;3:e28780. doi: 10.4161/onci.28780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Golden EB, Demaria S, Schiff PB, Chachoua A, Formenti SC. An abscopal response to radiation and ipilimumab in a patient with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunol Res. 2013;1(6):365–72. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hiniker SM, Chen DS, Reddy S, Chang DT, Jones JC, Mollick JA, et al. A systemic complete response of metastatic melanoma to local radiation and immunotherapy. Transl Oncol. 2012;5(6):404–7. doi: 10.1593/tlo.12280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Postow MA, Callahan MK, Barker CA, Yamada Y, Yuan J, Kitano S, et al. Immunologic correlates of the abscopal effect in a patient with melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(10):925–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stamell EF, Wolchok JD, Gnjatic S, Lee NY, Brownell I. The abscopal effect associated with a systemic anti-melanoma immune response. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85(2):293–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kachikwu EL, Iwamoto KS, Liao YP, DeMarco JJ, Agazaryan N, Economou JS, et al. Radiation enhances regulatory T cell representation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81(4):1128–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strigari L, Mancuso M, Ubertini V, Soriani A, Giardullo P, Benassi M, et al. Abscopal effect of radiation therapy: Interplay between radiation dose and p53 status. Int J Radiat Biol. 2014;90(3):248–55. doi: 10.3109/09553002.2014.874608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Camphausen K, Moses MA, Menard C, Sproull M, Beecken WD, Folkman J, et al. Radiation abscopal antitumor effect is mediated through p53. Cancer Res. 2003;63(8):1990–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yuan J, Adamow M, Ginsberg BA, Rasalan TS, Ritter E, Gallardo HF, et al. Integrated NY-ESO-1 antibody and CD8+ T-cell responses correlate with clinical benefit in advanced melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(40):16723–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110814108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohba K, Omagari K, Nakamura T, Ikuno N, Saeki S, Matsuo I, et al. Abscopal regression of hepatocellular carcinoma after radiotherapy for bone metastasis. Gut. 1998;43(4):575–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.4.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waters JP, Pober JS, Bradley JR. Tumour necrosis factor and cancer. J Pathol. 2013;230(3):241–8. doi: 10.1002/path.4188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakanishi M, Chuma M, Hige S, Asaka M. Abscopal effect on hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(5):1320–1. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01782_13.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ledezma B, Binder S, Hamid O. Atypical clinical response patterns to ipilimumab. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15(4):393–403. doi: 10.1188/11.CJON.393-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dovedi SJ, Adlard AL, Lipowska-Bhalla G, McKenna C, Jones S, Cheadle EJ, et al. Acquired Resistance to Fractionated Radiotherapy Can Be Overcome by Concurrent PD-L1 Blockade. Cancer Res. 2014;74(19):5458–68. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Park HJ, Griffin RJ, Hui S, Levitt SH, Song CW. Radiation-induced vascular damage in tumors: implications of vascular damage in ablative hypofractionated radiotherapy (SBRT and SRS) Radiat Res. 2012;177(3):311–27. doi: 10.1667/rr2773.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barker CA, Postow MA, Khan SA, Beal K, Parhar PK, Yamada Y, et al. Concurrent radiotherapy and ipilimumab immunotherapy for patients with melanoma. Cancer Immunol Res. 2013;1(2):92–8. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kanegasaki S, Matsushima K, Shiraishi K, Nakagawa K, Tsuchiya T. Macrophage inflammatory protein derivative ECI301 enhances the alarmin-associated abscopal benefits of tumor radiotherapy. Cancer Res. 2014;74(18):5070–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dewan MZ, Galloway AE, Kawashima N, Dewyngaert JK, Babb JS, Formenti SC, et al. Fractionated but not single-dose radiotherapy induces an immune-mediated abscopal effect when combined with anti-CTLA-4 antibody. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(17):5379–88. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Akutsu Y, Matsubara H, Urashima T, Komatsu A, Sakata H, Nishimori T, et al. Combination of direct intratumoral administration of dendritic cells and irradiation induces strong systemic antitumor effect mediated by GRP94/gp96 against squamous cell carcinoma in mice. Int J Oncol. 2007;31(3):509–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Teitz-Tennenbaum S, Li Q, Rynkiewicz S, Ito F, Davis MA, McGinn CJ, et al. Radiotherapy potentiates the therapeutic efficacy of intratumoral dendritic cell administration. Cancer Res. 2003;63(23):8466–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nikitina EY, Gabrilovich DI. Combination of gamma-irradiation and dendritic cell administration induces a potent antitumor response in tumor-bearing mice: approach to treatment of advanced stage cancer. Int J Cancer. 2001;94(6):825–33. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20011215)94:6<825::aid-ijc1545>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Siva S, Callahan J, MacManus MP, Martin O, Hicks RJ, Ball DL. Abscopal effects after conventional and stereotactic lung irradiation of non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8(8):e71–2. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318292c55a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ishiyama H, Teh BS, Ren H, Chiang S, Tann A, Blanco AI, et al. Spontaneous regression of thoracic metastases while progression of brain metastases after stereotactic radiosurgery and stereotactic body radiotherapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: abscopal effect prevented by the blood-brain barrier? Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2012;10(3):196–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tubin S, Casamassima F, Menichelli C, Pastore G, Fanelli A, Crisci R. A Case Report on Metastatic Thyroid Carcinoma: Radiation-induced Bystander or Abscopal Effect? J Cancer Sci Ther. 2012;4:408–11. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Okuma K, Yamashita H, Niibe Y, Hayakawa K, Nakagawa K. Abscopal effect of radiation on lung metastases of hepatocellular carcinoma: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:111. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-5-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cotter SE, Dunn GP, Collins KM, Sahni D, Zukotynski KA, Hansen JL, et al. Abscopal effect in a patient with metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma following radiation therapy: potential role of induced antitumor immunity. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147(7):870–2. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lakshmanagowda PB, Viswanath L, Thimmaiah N, Dasappa L, Supe SS, Kallur P. Abscopal effect in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia during radiation therapy: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:204. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-2-204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Takaya M, Niibe Y, Tsunoda S, Jobo T, Imai M, Kotani S, et al. Abscopal effect of radiation on toruliform para-aortic lymph node metastases of advanced uterine cervical carcinoma--a case report. Anticancer Res. 2007;27(1):499–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wersall PJ, Blomgren H, Pisa P, Lax I, Kalkner KM, Svedman C. Regression of non-irradiated metastases after extracranial stereotactic radiotherapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Acta Oncol. 2006;45(4):493–7. doi: 10.1080/02841860600604611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nam SW, Han JY, Kim JI, Park SH, Cho SH, Han NI, et al. Spontaneous regression of a large hepatocellular carcinoma with skull metastasis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20(3):488–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sham RL. The abscopal effect and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Am J Med. 1995;98(3):307–8. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(99)80380-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.MacManus MP, Harte RJ, Stranex S. Spontaneous regression of metastatic renal cell carcinoma following palliative irradiation of the primary tumour. Ir J Med Sci. 1994;163(10):461–3. doi: 10.1007/BF02940567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rees GJ, Ross CM. Abscopal regression following radiotherapy for adenocarcinoma. Br J Radiol. 1983;56(661):63–6. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-56-661-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fairlamb DJ. Spontaneous regression of metastases of renal cancer: A report of two cases including the first recorded regression following irradiation of a dominant metastasis and review of the world literature. Cancer. 1981;47(8):2102–6. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810415)47:8<2102::aid-cncr2820470833>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Antoniades J, Brady LW, Lightfoot DA. Lymphangiographic demonstration of the abscopal effect in patients with malignant lymphomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1977;2(1–2):141–7. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(77)90020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kingsley DP. An interesting case of possible abscopal effect in malignant melanoma. Br J Radiol. 1975;48(574):863–6. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-48-574-863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ehlers G, Fridman M. Abscopal effect of radiation in papillary adenocarcinoma. Br J Radiol. 1973;46(543):220–2. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-46-543-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kodama K, Higashiyama M, Okami J, Tokunaga T, Inoue N, Akazawa T, et al. A possible abscopal effect of post-irradiation immunotherapy in two patients with metastatic lung tumors. Int Cancer Conf J. 2014;3(2):122–7. [Google Scholar]