Abstract

We asked if the higher work of breathing (Wb) during exercise in women compared with men is explained by biological sex. We created a statistical model that accounts for both the viscoelastic and the resistive components of the total Wb and independently compares the effects of biological sex. We applied the model to esophageal pressure-derived Wb values obtained during an incremental cycle test to exhaustion. Subjects were healthy men (n = 17) and women (n = 18) with a range of maximal aerobic capacities (V̇o2 max range: men = 40-68 and women = 39–60 ml·kg−1·min−1). We also calculated the dysanapsis ratio using measures of lung recoil and forced expiratory flow as index of airway caliber. By applying the model we found that the differences in the total Wb during exercise in women are due to a higher resistive Wb rather than viscoelastic Wb. We also found that the higher resistive Wb is independently explained by biological sex. To account for the known effect of lung volumes on the dysanapsis ratio we compared the sexes with an analysis of covariance procedures and found that when vital capacity was accounted for the adjusted mean dysanapsis ratio is statistically lower in women (0.17 vs. 0.25 arbitrary units; P < 0.05). Our collective findings suggest that innate sex-based differences may exist in human airways, which result in significant male-female differences in the Wb during exercise in healthy subjects.

Keywords: airways, expiratory flow limitation, mechanical ventilatory constraints, sex differences

the maximum expiratory flow-volume (MEFV) curve is widely used as an index of human lung function. Although values are generally reproducible within an individual, there exists considerable between-individual variation, even when subjects are matched for age, height, and sex. Green et al. (11) proposed that individuals with similar lung volumes do not necessarily have similar airway diameters. The loose coupling between airway size and lung volume has been termed “dysanapsis” and provides, in large part, the basis for between-subject variability in expiratory flows. As a corollary to the original concept of dysanapsis, Mead (22) demonstrated significant sex-based differences where women have airways that are smaller relative to lung size than are those of men. We re-examined the concept of dysanapsis using high-resolution computed tomography and found that when older men and women are matched for lung size, the airway luminal areas of larger conducting airways are significantly smaller in women (29). Given that the main sites of airway resistance are the larger airways, and that the smaller airways contribute <20% of total resistance, a woman matched for lung size to a man would have higher airway resistance, particularly during conditions of high ventilation such as exercise.

Based on the abovementioned sex-based difference in airway size measured in older ex-smokers and approximated in young healthy individuals using the dysanapsis ratio, it would be expected that respiratory mechanics would differ between men and women under the high ventilatory demands of dynamic whole body exercise. For example, there is evidence to suggest that young women, free from respiratory disease, experience expiratory flow limitation (EFL) more frequently and at a lower absolute ventilation (V̇e) than men (8, 19, 32) although direct comparisons between men and women have, to date, been few (9, 14, 33). Furthermore, we have shown that for a given V̇e, the mechanical work of breathing (Wb) is significantly higher in women relative to men (9, 14), principally due to a higher resistive Wb (13). However, there are two considerations of our previous work that merit attention. First, all participants were endurance trained and therefore able to achieve high V̇e. Relative to untrained subjects, the greater V̇e achieved by endurance-trained athletes requires high flows, which greatly increases resistance to airflow and consequently the resistive Wb. As such, our reported sex difference in total Wb, and specifically the resistive component of Wb, may simply be related to the high V̇e achieved only by highly trained individuals. Second, our previous use of the dysanapsis ratio was done by estimating static recoil pressure (Pst) (8). To make comprehensive comparisons between the sexes, any variations in Pst must be accounted for to accurately measure dysanapsis (3).

The purpose of this study was twofold. First, we sought to comprehensively characterize sex-based differences in the Wb during exercise. Specifically, we created a model that accounts for viscoelastic and resistive components of the total Wb and independently compares the effects of biological sex. The model was applied to esophageal pressure-derived Wb values obtained from healthy men and women with a range of aerobic capacities and statures. Second, we revisited the concept of dysanapsis and how it may relate to sex-based differences in the Wb. We hypothesized that there would be no effect of sex on the component of our model that describes viscoelastic Wb, whereas, the aspect describing resistive Wb would demonstrate a sex effect. As mentioned above, sex differences in the resistive Wb are likely attributable to differences in airway caliber; however, no previous study has explicitly tested this hypothesis. Accordingly, we hypothesized that compared with men, women would exhibit a smaller dysanapsis ratio, which is indicative of smaller airways.

METHODS

Subjects.

Healthy men (n = 17) and women (n = 18) between the ages of 19 and 55 yr were recruited to participate in this study. Subjects were excluded if they were smokers or had a history of cardiopulmonary disease. All procedures received ethical approval from the University of British Columbia Clinical Ethics board and conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki. Subjects over the age of 45 yr (n = 4, 3 women) did not complete the maximal exercise test (described below). Previously, our laboratory demonstrated significant inter- and intrasubject variability with respect to hormone levels throughout the menstrual cycle (17); therefore, we tested the women at random points throughout their menstrual cycle and oral contraceptives were not an exclusion criterion.

Experimental overview.

Testing took place over 2 days. During the first day, informed consent, anthropometric and descriptive data were obtained. Subsequently, subjects underwent routine pulmonary function testing including plethsymography and spirometry. On the second testing day, subjects were instrumented with an esophageal balloon catheter to assess static recoil pressure of the lungs and chest wall. After measuring static recoil, a rest period (∼10–15 min) was completed on the cycle ergometer followed by an incremental test to exhaustion.

Pulmonary function.

Pulmonary function was completed in a calibrated whole-body plethysmograph (V62J Body Plethysmograph; SensorMedics, Yorba Linda, CA). Whole body plethymography was used to assess lung volumes including: total lung capacity (TLC), vital capacity (VC), functional residual capacity (FRC), and residual volume (RV). Spirometry was used to determine forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expired volume in 1 s (FEV1), and midexpiratory flows (FEF25–75). All procedures were completed in accordance to standardized guidelines (2) and expressed as percent predicted values (6, 23).

Static recoil.

Static recoil of the respiratory system was determined in every subject using previously described techniques (31). Each subject was instrumented with an esophageal balloon catheter and three-lead electrocardiogram as we have described elsewhere (7). After balloon placement, the subjects breathed on an apparatus consisting of large bore tubing (5-cm inner diameter) connecting a mouthpiece to a three-way valve. The three positions of the valve were as follows: open to room air, in-line with a rolling seal spirometer (Ohio Medical Products Model 822, Madison, WI), and occlusion. Initially subjects breathed while the circuit was open to room air. Subjects then inspired maximally to TLC at which time the valve was manually switched so that the subject expired passively into the spirometer. The valve was then switched to occlusion when the subject reached 50% of his or her VC. During this time, the subjects were instructed to relax their respiratory muscle and avoid movement for ∼1–2 s. In a subset of individuals (n = 7, 4 women), the static recoil pressure was also determined at other lung volumes (90, 80, 70, and 60% VC). We found that static recoil pressure- decreased three times as much from 90-70% VC compared with 70-50% VC (P < 0.01), which is in excellent agreement with other published values (31). We also took several other precautions to ensure we made consistent and appropriate assessments of static recoil pressure. First, subjects were familiarized with the maneuver before the second testing day and had ample opportunity to practice before insertion of the esophageal balloon catheter. Second, once the esophageal balloon catheter was placed, several practice trials were again performed. Third, once their performance was deemed satisfactory, the subjects repeated the measure >10 times. Our overall coefficient of variation and standard deviation for each subject was 10 ± 1 and 8 ± 1% and 0.54 ± 0.29 and 0.32 ± 0.1% for men and women, respectively. Fourth, a trial was discarded if the subject did not obtain peak negative esophageal pressure during the initial inspiration to TLC. Fifth, if the expired volume during occlusion was not with 50 ml of the target, the trial was disregarded. Consequently, the volume during occlusion was not always precisely at 50% VC. However, 50 ml only represents a change of 1.5% in our subject with the smallest VC and <1% for the average. We also did not observe any within subject trends (with each subject having some above and below) or between sex trends (men's target VC 3.06 ± 0.33 actual VC 3.08 ± 0.40, women's target VC 2.04 ± 0.25 actual VC 2.00 ± 0.27). Lastly, during the occlusion, we took the average static pressure between each cardiac artifact, as verified by a three-lead electrocardiogram.

Dysanapsis.

We determined dysanapsis ratio using the methods described by Mead (22), whereby a measurement sensitive to lung size is related to a measurement sensitive to airway size. In the present study, we used VC (measured by whole body plethymography) as a measure of lung size. An index of airway size, or dysanapsis, was assessed using a functional measure consisting of forced expiratory flow at 50% VC (FEF50), VC, and static recoil pressure at 50% VC [Pst(l)50], which is given by the following equation:

| (1) |

In our previous study (8), we used published regression estimates of static recoil pressure (31) based on the following equation:

| (2) |

We then determined dysanapsis using the following equation:

| (3) |

To address the concern (3) that the calculation of dysanapsis using predicted static recoil pressure at 50% VC [Pst(l)50predicted] will not accurately reflect true dysanapsis in all individuals, we compared dysanapsis based on both measured (Eq. 1) and predicted Pst(l)50 (Eq. 3).

Maximal exercise testing.

Subjects completed an incremental step-wise cycle test to exhaustion on an electromagnetically braked ergometer (Excalibur Sport; Lode, Groningen, The Netherlands). After a self-selected warm-up (∼10 min), subjects began at a work rate of 80 W (women) or 120 W (men). Work increased by 20 W every 2 min for both sexes and the test was terminated when a pedal cadence of 60 rpm could not be maintained despite verbal encouragement. Maximal expiratory flow-volume curves were collected and analyzed taking into account for exercise-induced bronchodilation and thoracic gas compression to not overestimate the degree of EFL (12).

Flow, pressure, and volume.

Ventilatory and mixed expired parameters were gathered using a customized metabolic cart (7). The resistance of the breathing circuit was between 0.6 and 0.9 cmH2O·l−1·s−1 at flows of 0.5–8 l/s. Esophageal pressure was determined by connecting the distal end of the balloon catheter to a piezoelectric pressure transducer (Raytech Instruments, Vancouver, BC, Canada). Mouth pressure was assessed via a port in the mouthpiece, which was connected to a nonrebreathing valve (2700B; Hans Rudolph, Kansas City, MO) and was transduced with the same piezoelectric transducer. Transpulmonary pressure was taken as the difference between mouth pressure and esophageal pressure. During exercise, volume was obtained by numerical integration of the flow signals. End-tidal CO2 was determined via a port in the mouthpiece connected to a gas analyzer. Metabolic volumes (V̇o2, V̇co2) are expressed in STPD, whereas all other volumes are shown in BTPS. During all testing, raw data (flow, pressure, volume, and expired gases) were recorded continuously at 200 Hz using a 16-channel analog-to-digital data acquisition system (PowerLab/16SP model ML 795; ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO) and stored on a personal computer for subsequent analysis. To determine operational lung volumes, subjects performed an inspiratory capacity (IC) maneuvers during each stage. At the 1-min-30-s mark, the subject was given the prompt for the IC maneuver: ''at the end of a normal breath out, take a maximal breath all the way in.'' The investigators were provided with online visual feedback of the volume trace to ensure there was no dramatic change in end-expiratory lung volume (EELV) before the IC maneuver. If the IC maneuver was not performed adequately, the investigators prompted another IC maneuver to be performed before the end of the stage. For IC analysis, 5–10 breaths before the IC maneuver were selected to correct for any pneumotachograph drift. Drift was corrected by drawing a linear regression line for each EELV over time and solving for the last IC maneuver (10). The EELV was calculated by subtracting the IC volume from the TLC volume, whereas end-inspiratory lung volume (EILV) was calculated as the sum of tidal volume and EELV. To determine tidal FV loops, ∼15–20 tidal breaths (or 30 s) before an IC maneuver were composite averaged and placed within the MEFV curve according to the measured EELV. The magnitude of EFL was calculated by dividing the volume of the tidal breath that contacted the MEFV curve by the tidal volume. This value was then expressed as a percentage where subjects with a value of 5% or less were considered nonflow limited; all other subjects were considered flow limited. The Wb was determined as previously described (7). Briefly, with the use of the same data as the flow-volume composite, esophageal-pressure volume loops were created in a similar fashion. Afterwards, using EELV we constructed Campbell diagrams to determine the Wb and split it into its constituent resistive, elastic and inspiratory, expiratory aspects.

Work of breathing model.

We used the model shown in Eq. 4 to specify the relationship between the total Wb and V̇e:

| (4) |

where Wbi,j is the jth observation taken on the ith individual; αi and βi are subject level random effects for the ith individual following independent normal distributions with zero means and standard σα and σβ, respectively; S = 0 for males and 1 for females; t and u are the sex effects influencing Wb; and ε denotes the independent, normally distributed (mean 0 and standard deviation σε) measurement error. The number of Wb taken per individual ranged from 8 to 14 in men and 7 to 14 in women. Since we used all observations of Wb taken on each individual, the model specified in Eq. 4 is a type of repeated-measures analysis. Under this statistical framework, the subject level effects (i.e., αi and βi) allow each individual to have different coefficients for V̇E3 and V̇E2, respectively, but also allow for population level estimates of the population level parameters a, b, t, and u.

If there was no effect of biological sex then both t and u would be equal to zero and the expected Wb could be described as in Eq. 5:

| (5) |

Equation 5 is the model originally proposed by Rohrer (27) and Otis et al. (24), and it is how we previously quantified sex-based difference in the Wb (14). When there are no sex effects, a and b can be viewed as the population average coefficients for V̇E3 and V̇E2, respectively. On the other hand, if the coefficient for V̇E3 is different for each sex, then the population level coefficient for V̇E3 is a for males and (a + t) for females. Similarly, if the impact of V̇E2 on Wb is different for each sex, then the population level coefficient for V̇E2 is b for males and (b + u) for females. The model in Eq. 4 was fit to the data using commercially available software [JMP, Version 11.2 (2013); SAS Institute, Cary, NC] via restricted maximum likelihood (25, 26).

Statistical analysis.

Descriptive characteristics, pulmonary function, and maximal exercise data between men and women were compared with unpaired t-tests. All values were examined and met the assumption of being normally distributed as assessed by a Shapiro-Wilk test. To compare the dysanapsis ratio at a given lung volume we used an analysis of covariance test, whereby VC is the covariate variable. We first ensured the assumption of homogeneity of the regression was met between men and women (P > 0.05). We then compared the adjusted means for the dysanapsis ratio. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05 for all statistical comparisons. Values are presented as means ± SD unless otherwise noted.

RESULTS

Subject characteristics and pulmonary function.

Table 1 summarizes basic descriptive characteristics and pulmonary function data. Men and women were not different for age, but men were taller and heavier. All subjects were within the normal range for body mass index, and pulmonary function values were within predicted values. When expressed in absolute terms, men had higher lung volumes and flows, but when expressed as percent predicted no differences were apparent. Table 2 summarizes maximal exercise data. Men had a higher maximal V̇o2 in both absolute (l/min) and relative (ml·kg−1·min−1) terms, but men and women were similar when expressed as percent predicted.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics and pulmonary function variables

| Men (n = 17) | Women (n = 18) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 30 ± 9 | 32 ± 9 |

| Height, cm | 181 ± 6 | 167 ± 7* |

| Mass, kg | 76 ± 9 | 65 ± 7* |

| BMI, kg/m | 23.1 ± 1.9 | 23.3 ± 2.2 |

| BSA, m2 | 1.95 ± 0.1 | 1.72 ± 0.1* |

| FVC, liter | 5.9 ± 0.8 | 4.2 ± 0.5* |

| FVC, %predicted | 105 ± 11 | 108 ± 7 |

| FEV1, liter | 4.6 ± 0.8 | 3.3 ± 0.5* |

| FEV1, %predicted | 98 ± 12 | 98 ± 10 |

| FEV1/FVC | 78 ± 5 | 77 ± 5 |

| FEV1/FVC, %predicted | 92 ± 5 | 91 ± 6 |

| PEF, l/s | 10.8 ± 1.3 | 7.8 ± 1.3* |

| FEF25, l/s | 8.8 ± 1.3 | 7.0 ± 1.4* |

| FEF50, l/s | 5.0 ± 1.3 | 3.9 ± 1.0* |

| FEF75, l/s | 2.0 ± 0.9 | 1.3 ± 0.5* |

| TLC, liter | 7.8 ± 0.9 | 5.7 ± 0.9* |

| TLC, %predicted | 107 ± 11 | 107 ± 10 |

| VC, liter | 6.1 ± 0.7 | 4.1 ± 0.5* |

| VC, %predicted | 105 ± 10 | 106 ± 10 |

| IC, liter | 3.8 ± 0.6 | 2.6 ± 0.5* |

| IC, %predicted | 103 ± 15 | 107 ± 16 |

| FRC, liter | 4.0 ± 0.6 | 3.1 ± 0.5* |

| FRC, %predicted | 106 ± 17 | 104 ± 16 |

| ERV, liter | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.3* |

| ERV, %predicted | 104 ± 18 | 112 ± 28 |

| RV, liter | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.4 |

| RV, %predicted | 104 ± 20 | 104 ± 26 |

| Pst50, cmH2O | 4.77 ± 1.2 | 4.70 ± 1.0 |

| Pst50 predicted,† cmH2O | 4.62 ± 0.5 | 4.53 ± 0.5 |

| %Difference | 14 ± 14 | 17 ± 15 |

| Dysanapsis, AU | 0.198 ± 0.050 | 0.204 ± 0.057 |

| Dysanapsis predicted, AU | 0.186 ± 0.032 | 0.213 ± 0.047 |

Values are means ± SD. BMI, body mass index; BSA, body surface area; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1, forced expired volume in 1 s; PEF, peak expiratory flow; FEF25, forced expired flow after 25% volume expired; FEF50, forced expired flow after 50% volume expired; FEF75, forced expired flow after 75% volume expired; TLC, total lung capacity; VC, vital capacity; IC, inspiratory capacity; FRC, functional residual capacity; ERV, expiratory reserved volume; RV, residual volume; Pst50, static recoil at 50% vital capacity; AU, arbitrary units.

P > 0.05, significantly different from men.

Predicted values obtained from previous regression from Turner et al. (31).

Table 2.

Mean data at maximal exercise for men and women

| Men (n = 16) | Women (n = 15) | |

|---|---|---|

| V̇o2, l/min | 4.2 ± 0.7 | 3.0 ± 0.4* |

| V̇o2, ml·kg−1·min−1 | 56 ± 8 | 48 ± 6* |

| V̇o2, %predicted | 123 ± 16 | 126 ± 17 |

| V̇co2, l/min | 4.6 ± 0.8 | 3.2 ± 0.4* |

| RER | 1.11 ± 0.05 | 1.08 ± 0.06 |

| VT, liter | 3.0 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.3* |

| Fb, breaths/min | 55 ± 11 | 60 ± 9 |

| V̇e, l/min | 161 ± 31 | 116 ± 13* |

| V̇e/V̇o2 | 39 ± 6 | 39 ± 5 |

| V̇e/V̇o2 | 35 ± 5 | 36 ± 3 |

| PetCO2, mmHg | 28 ± 4 | 27 ± 4 |

| Te, % | 51 ± 1.7 | 52 ± 2.3 |

| Workload, W | 299 ± 47 | 219 ± 27* |

| EELV, %TLC | 51 ± 5 | 56 ± 6* |

| EILV, %TLC | 87 ± 5 | 89 ± 4 |

| ΔPeso, cmH2O | 51 ± 12 | 47 ± 7 |

| Wb, J/min | 564 ± 201 | 377 ± 104* |

| V̇eCAP, l/min | 212 ± 30 | 167 ± 22* |

| V̇e/V̇eCAP, % | 76 ± 9 | 70 ± 8 |

Values are means ± SD. V̇o2, oxygen consumption; V̇co2, carbon dioxide production; RER, respiratory exchange ratio; VT, tidal volume; Fb, breathing frequency; V̇e, minute ventilation; PetCO2, end-tidal carbon dioxide; EELV, end-expiratory lung volume; EILV, end-inspiratory lung volume; ΔPeso, esophageal pressure swings; Wb, work of breathing; V̇eCAP, ventilatory capacity.

P > 0.05, significantly different compared with men.

Work of breathing model.

The model outlined in Eq. 4 was fit to the experimental data, and the results of fitting the model are summarized in Table 3. The table reports marginal P values for the fixed effects. The overall model fit had an adjusted R2 > 0.98, which was similar between the sexes, and model diagnostics indicated that modeling assumptions were not violated. There are several inferential procedures we could have used to identify the significant effects in our model. We used a forward selection procedure as well as a backward selection procedure as detailed below.

Table 3.

Marginal P values for fixed effects specified in Eq. 4

| Term | t-Ratio | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| a | −1.39 | 0.1804 |

| b | 6.16 | <0.0001 |

| t | 2.16 | 0.0394 |

| u | 0.47 | 0.6408 |

See text for detailed description of terms.

Above in Eq. 4, we specified a model for the Wb model:

| (4) |

The model was fit to all of the observations (i.e., all measurements for all participants) using the JMP statistical software package via the “Fit model” procedure and specifying random effects αi and βi for individual level coefficients of the predictors V̇E3 and V̇E2, respectively. A model with no intercept was chosen to reflect that Wb = 0 when V̇E3 = 0.

Our statistical software package (JMP) reports a marginal t-statistic for each parameter in the model. For a specific parameter, this statistic tests the hypothesis that the parameter of interest is different from zero, conditional on the presence of all other parameters in the model fit being in the model. The t-statistic that is computed is a type of the Wald statistic that takes the ratio of the parameter estimate to its standard error.

Selecting the “best” model for the data using marginal t-tests for random effects models is not straightforward because when assessing whether or not there is significant evidence to include a parameter in the model, it is conditional on the other parameters also being in the model. To address this, we considered two procedures that utilize the marginal tests: 1) forward selection; and 2) backward selection.

For the forward selection (1), we begin with a base model (initially a model with no fixed effects: a, b, t, and u) but with the individual level random effects. Next, we consider adding to the model a parameter that is not currently included, and the parameter that has the smallest marginal P value (<0.05) is identified as significant. That is, the “most significant” parameter is identified. This selected parameter is now included in the updated base model. The procedure of adding the most significant parameter to the base model is continued until either all parameters have been added to the model or there are no significant parameters to add conditional on the current base model. Finally, we can “prune” the fit by fitting the final base model and deleting the most insignificant term (the parameter with the largest P > 0.05). The pruning continues until there are no insignificant effects. The parameters left in the model after pruning are identified as significant.

For our data, the steps for the forward selection procedure are summarized in Table 4. At each step we begin with a base model and consider adding terms, conditional on the base model. In the stage 1, the base model contains no fixed effects. We consider adding a term to the model by including a single parameter in the base model and computing the marginal P value. The most significant parameter is b and is therefore included in the base model. In stage 2, the base model contains the fixed effect b and marginal P values are computed for each remaining candidate parameter. In this case, the most significant term, conditional on the presence of b in the model, is t. Finally, in stage 3, the base model contains both b and t. Since, conditional on the presence of b and t in the model, neither of the remaining parameters have a small P value, the procedure stops. The model selected by forward selection is

| (6) |

Table 4.

Forward selection procedure

| Stage/Term Added | Marginal P Value |

|---|---|

| Stage 1: base model: Wbi,j = αiV̇E3 + βiV̇E2 + ϵi,j | |

| a | 0.0956 |

| b | <10−14* |

| t | 0.0279 |

| u | <10−11 |

| Stage 2: base model: Wbi,j = αiV̇E3 + (b + βi)V̇E2 + ϵi,j | |

| a | 0.0540 |

| t | 0.0079* |

| u | 0.1322 |

| Stage 3: base model: Wbi,j = (αi + tS)V̇E3 + (b + βi)V̇E2 + ϵi,j | |

| a | 0.1227 |

| u | 0.3420 |

See text for detailed description of terms.

Conversely to forward selection procedures, the backward selection (2) begins with all terms in the model and sequentially removes the least important. In our procedure, we begin with a base model containing all fixed effects (a, b, t, and u) and also the individual level random effects. Next, each term is assessed in the presence of all fixed effects currently in the model. The parameter that has the largest marginal P value (>0.05) is identified as not significant. That is, the “least significant” parameter is identified. This selected parameter is removed from the based model. The process of removing the least significant parameter from the base model is continued until either all terms have been removed or until there are no terms with a marginal P< 0.05.

The backward selection results for the Wb data in our study are summarized in Table 5. The term removed from the model are shown with an asterisk. At stage 1, all fixed effects are entertained, and in the presence of the other effects, we identify u as the least significant effect. The base model in stage 2 is the same as stage 1, except that u has been deleted. At this stage, a is the only term with a marginal P > 0.05 and is thus removed from the model. Finally, at stage 3, the terms b and t are left and both significant. The final model from the backward selection is similar to that determined from forward selection (see Eq. 6). Specifically, both approaches arrived at the same conclusions demonstrating that there were two significant effects in the model (using P < 0.05 in each stage of the selection procedures): b and t.

Table 5.

Backward selection procedure

| Stage/Term Added | Marginal P Value |

|---|---|

| Stage 1: base model: Wbi,j = (a + αi + tS)V̇E3 + (b + βi+ uS)V̇E2 + ϵi,j | |

| a | 0.1804 |

| b | <10−6 |

| t | 0.0394 |

| u | 0.6408* |

| Stage 2: base model: Wbi,j = (a + αi + tS)V̇E3 + (b + βi)V̇E2 + ϵi,j | |

| a | 0.1227* |

| b | <10−15 |

| t | 0.0197 |

| Stage 3: base model: Wbi,j = (αi + tS)V̇E3 + (b + βi)V̇E2 + ϵi,j | |

| b | <10−15 |

| t | 0.0079 |

See text for detailed description of terms.

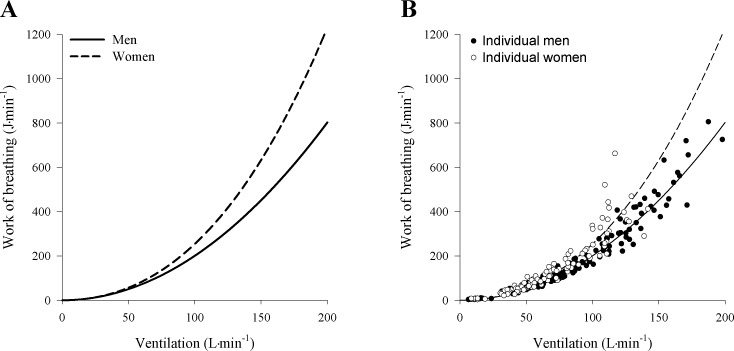

The effect for t indicates that there is a significant sex difference that manifests itself in the coefficient of V̇E3, which represents the work done in overcoming the resistance to turbulent flow. The effect for b manifests itself in the coefficient of V̇E2, which represents the mechanical work done in overcoming the viscous resistance offered by the lung tissues to deformation and by the respiratory tract to the laminar flow of air. While the effect for b contributed significantly to the overall model, there was no observed sex effect on the viscoelastic Wb. The estimated expected Wb curves from the fitted model is displayed in Fig. 1, and the data support a model where the Wb for females is, on average, higher than for males.

Fig. 1.

Relationship between work of breathing and ventilation in men and women during maximal exercise. A: curves were developed using the model described above for each subject and subsequently averaged for men and women. Equations for the average curve are as follows: men, y = 2.007 × 102 × V̇E2; women, y = 2.007 × 10−2 × V̇E2 + 5.355 × 10−5 × V̇E3. B: individual data for men and women.

Lung volumes and dysanapsis.

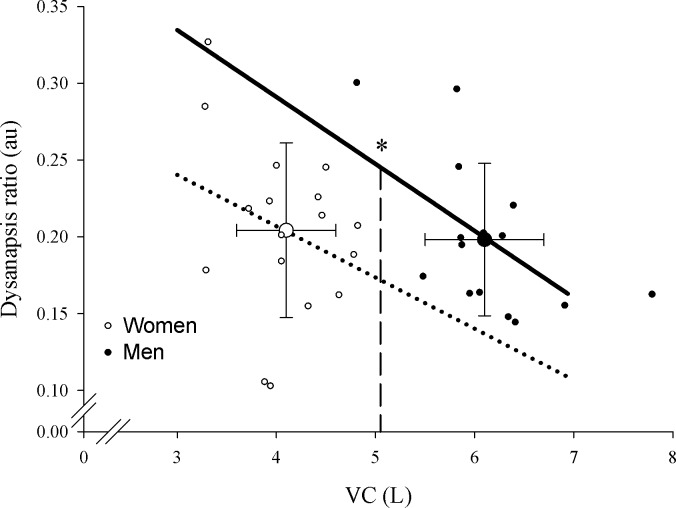

As a group, women had significantly lower absolute values for FVC, VC, IC, FRC, and expiratory reserve volume (Table 1). However, when expressed as a fraction of normative values men and women were not different for lung volumes. Measured and predicted Pst(l)50 values were similar between men and women (P > 0.05) where the predicted Pst(l)50 was on average 14–17% lower than measured values. The dysanapsis ratio was determined using both measured and predicted Pst(l)50, and in both instances the ratio was statistically similar between men and women (Table 2; Fig. 2). The fact that there was no significant difference in dysanapsis ratio between men and women is explained by the significantly smaller VC in women. To account the known effect of absolute lung volumes on the dysanapsis ratio we compared the sexes with an analysis of covariance procedures. Figure 2 shows that when VC is corrected for the adjusted mean dysanapsis ratio is statistically lower in women (P < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Dysanapsis ratio in men and women. The large open and filled circles represent the average vital capacity and dysanapsis ratio in women and men, respectively, with no difference being found in dysanapsis ratio. The small circles are individual data points for men (filled) and women (open). The lines represent the group regression for dysanapsis and vital capacity. VC, vital capacity; au, arbitrary units. *P < 0.05, significantly different regressions at isovital capacities.

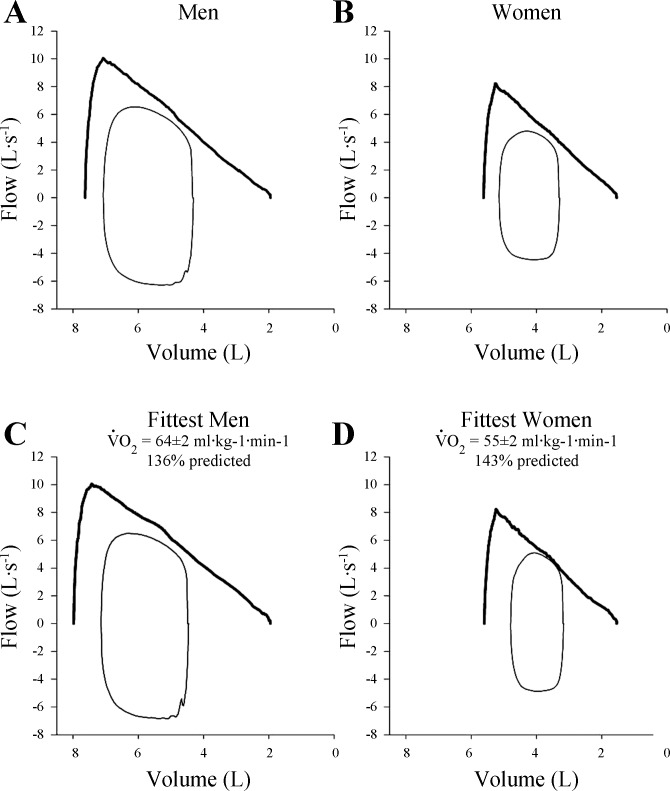

Mechanical ventilatory constraint.

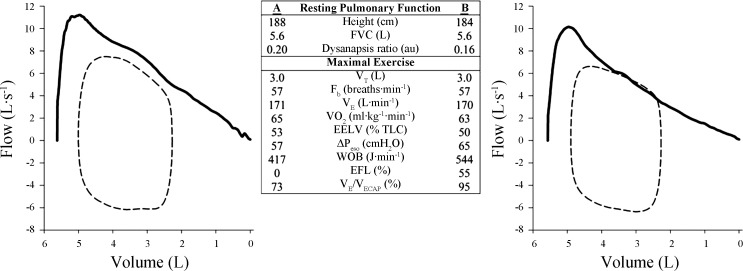

Figure 3 shows composite averages for tidal flow-volume loops at maximal exercise plotted relative to group mean MEFV loops for all men (Fig. 3A) and women (Fig. 3B). The occurrence of EFL was variable when considering the entire cohort of subjects, where 10 of 16 men and 9 of 15 women experienced EFL at maximal exercise. Figure 3, C and D, shows the flow-volume loops for the men and women with the highest aerobic capacities (V̇o2 max >125% predicted), respectively. We found that the higher V̇e in the fittest women was associated with significant EFL during heavy and maximal intensity exercise with all but one demonstrating >25% EFL. By contrast, only half of the most fit men demonstrated significant EFL, and one other male demonstrated “impending” EFL (20), where their tidal flow-volume loop approached the MEFV curve and developed its characteristic shape but did not fully intersect it. Figure 4 shows MEFV curves and maximal exercise flow-volume loops in two men with comparable general anthropometric characteristics, including lung size, as well as V̇o2 max and breathing pattern. However, the subject in Fig. 3B had a lower dysanapsis ratio (0.16 vs. 0.20) and presumably smaller airways. Thus, despite similar V̇e and breathing patterns, the subject in Fig. 3B had higher esophageal pressure swings, Wb, and fractional utilization of ventilatory capacity.

Fig. 3.

Maximal expiratory flow-volume curves and maximal exercise flow-volume loops in men and women. A and B: composite averages for all the men and women, respectively. C and D: composite averages for the fittest men (n = 6) and women (n = 5), respectively. Note that all graphs are scaled similarly.

Fig. 4.

Maximal expiratory flow-volume curves and maximal exercise flow-volume loops in 2 matched men. The men are similar in age, height, and lung size, but the subject in A has a smaller dysanapsis ratio and presumably airways. The subjects achieved similar maximal oxygen consumption and adopted comparable breathing patterns, but the subject in B has marked mechanical ventilatory constraints and a higher work of breathing. See text and Table 2 for definitions.

DISCUSSION

Main findings.

The main findings of this study are threefold. First, by applying our model we found evidence that the differences in the total Wb during exercise in women are due to higher resistive Wb rather than viscoelastic Wb. Furthermore, the higher resistive Wb can be independently explained by biological sex. Second, when lung volume is corrected for, women have a smaller dysanapsis ratio, which is indicative of narrower airways relative to men. Third, independent of biological sex, healthy individuals who possess a smaller dysanapsis ratio were found to more likely exhibit mechanical constraints during exercise, and this effect is magnified in subjects with a high aerobic capacity. Collectively, our findings suggest that innate sex-based differences exist in human airways, which result in significant male-female differences in the Wb during exercise in health.

Work of breathing.

At rest and during low levels of V̇e, there were no differences in Wb between men and women. However, as V̇e increases, the Wb in women significantly increases out of proportion to men (Fig. 1), which is consistent with our previous observations (14). Accordingly, with the use of the same model to describe the Wb as in our earlier work (see Eq. 5) (24, 27), the results of the current study also indicate that women had significantly higher total Wb. Furthermore, the additional Wb required to achieve a given V̇e in women relative to men was likely the result of the work required to overcome the resistance to turbulent flow. However, by employing the aforementioned approach (Eq. 5), the current findings suffer from the same limitation as our earlier work where the independent effect of sex on Wb is not accounted for (28). To address the question of sex- vs. size-based differences we applied a statistical model that accounts for the constitutive components of the total Wb and considers the independent effect of biological sex on each constant (Eq. 4). In our proposed model the individual level random effects that account for repeated measures are both significant where the only adjustable or measurable inputs to the system are V̇e and sex. Since b was important, then V̇e impacts the model through the quadratic term, which represents the mechanical work done to overcome the viscous resistance. Similarly, since t is active, then there is a significant sex-by-V̇E3 interaction, which supports our conclusion that Wb done in overcoming the resistance to turbulent flow is different for men and women. Furthermore, u was found to be nonsignificant meaning that the mechanical work done in overcoming the viscous resistance was similar between the sexes.

We found that the viscoelastic component of Wb showed a population effect but no sex interaction. The absence of an interaction here means that the viscoelastic Wb is an equally important contributor to the total Wb in men and women. In the case of the men, the viscoelastic resistance to laminar flow component described the majority of Wb (Fig. 1). From an anatomical perspective, our findings mean that the inherent elasticity of the lung parenchyma is similar between the sexes, which is supported by our observation that Pst50 was similar between men and women (Table 1). Our interpretation is commensurate with the findings of Colebatch et al. (5), who found that the lungs of men and women have the same intrinsic elasticity. We also found that the resistive component of total Wb was significantly different between men and women. We interpret the difference in resistive Wb to be related to women having smaller conducting airways (assuming gas composition is the same between men and women). On the other hand, if the branching of the airways were different between men and women this could, in part, explain the differences in the resistive Wb. However, we view this as an unlikely explanation for our findings. Based on postmortem morphometric measures, it is known that the differentiation of airways and airway branching patterns is complete by 16 wk of gestational age (30), and to our knowledge no sex differences have been reported (4).

Previously, our group has shown that aerobically trained women have a greater Wb compared with equally trained men (14). However, it is possible that our findings of sex differences in Wb could have been skewed by the high V̇e produced by endurance-trained subjects, which in turn results in high flows and greater resistances. Thus, constant a would only be different and significant because of the exponential rise in Wb observed at high or maximal V̇e. To address thus concern, our study recruited both aerobically trained and healthy active individuals with modest maximal V̇o2 and V̇e. Despite the lower V̇e, and therefore lack of overall population effect for constant a, we found a significant sex effect describing the resistive Wb. Accordingly, we propose that healthy women, irrespective of aerobic fitness, have a greater Wb for a given V̇e and this finding becomes amplified when flows are greater (as seen in trained individuals). It should be noted that despite the fact that these findings serve to corroborate our previous observations (14), the important question still remains; are the sex-based differences in the Wb the result of inherently smaller airways in women?

Dysanapsis.

For a given lung volume, we found that women have a significantly smaller dysanapsis ratio when the effect of lung size is statistically removed (Fig. 2). The calculation of the dysanapsis ratio (Eqs. 1 and 3) takes into account maximum expired flow (at 50% VC to ensure effort independence) divided by other factors accounting for changes in flow including VC (a surrogate for airway length), Pst, with airway diameter being the unaccounted for variable. Absolute lung size needs to be accounted for because of the linear relationship between VC and dysanapsis ratio. Specifically, when the dysanapsis ratio was compared between the sexes without accounting for VC, there were not significant differences between the sexes. As the length of airways increases so does resistance, which has the overall effect of decreasing the dysanapsis ratio as VC increases (15). For example, a subject with a large VC of 7 liters and dysanapsis ratio of 0.16 most likely does not have smaller airways than a person with a VC of 3.5 liters and a dysanapsis ratio of 0.22. However, when lung size was accounted for, we found that women have a smaller dysanapsis ratio. In the present study we used measured and predicted Pst(l)50 values to calculate the dysanapsis ratio and the observed sex difference was present regardless of which equation was used (Eqs. 1 or 3). Dysanapsis, or the relationship between the FEF at a given lung volume relative to lung volume, provides an assessment of the association between structure and function and is related to intrinsic airway size (22). As such, the lower ratio for a given VC we observed in women is indicative of smaller airways relative to men and is consistent with the original work of Mead (22), acoustic reflectance estimates of the trachea (18), and computed tomography measures (29). Assuming mixed laminar and turbulent flow, Mead (22) calculated that healthy adult men have airways that are ∼17% larger in diameter than are the airways of women and speculated that sex differences in the airways develop relatively late in the growth phase. Our study confirms the existence of a difference in the dysanapsis ratio between men and women when VC is accounted for and our estimates of differences in airway size are in good agreement with those of Mead (22). Unique to our investigation is the coupling of estimates of airway anatomy with a detailed assessment of lung mechanics during exercise (see Linking airways to mechanical ventilatory constraints).

Previously, we used predicted Pst(l)50 to compute and compare the dysanapsis ratio in a group of women (8). There are inherent limitations whenever using predictive equations and whenever possible direct measures are, of course, preferred. A valid critique of our previous approach is that the use of predicted rather than measured lung recoil could affect the calculation of dysanapsis and subsequent interpretation (3). Our current study speaks to this where we have made a direct comparison between predicted and measured Pst(l)50 and found no difference in the dysanapsis ratio when using the predicted or measured values. However, to have greater confidence in measures of the dysanapsis ratio we recommend the usage of measured Pst(l)50 as there is error associated with any predictive equation. We emphasize that application of any regression equation should be restricted to the population from which it was drawn. With respect to lung recoil it is important to note that age and smoking history can have a significant influence.

Linking airway size to mechanical ventilatory constraints.

Based on the work of others (1, 19, 22, 30) we have argued that women may be particularly susceptible to reaching the mechanical limits for inspiratory and expiratory pressure and flow development. In the present study we found that the incidence of EFL at maximal exercise was similar between men (10/16 subjects) and women (9/15 subjects), an observation that appears at odds with our previous work (14). However, subjects in the present study had a wide spectrum of aerobic capacities (V̇o2 max range: men = 40–68, women = 39–60 ml·kg−1·min−1), whereas Guenette et al. (14) exclusively studied highly trained athletes (V̇o2 max range: men = 59–85, women = 52–67 ml·kg−1·min−1). When subjects in the present study separated into those with a V̇o2 max >125% predicted (Fig. 3), half of the men (3/6 subjects) with a high V̇o2 max developed EFL. This is consistent with other studies, which show that some, but not all, trained men develop EFL with heavy exercise (16). By contrast, when examining the highly trained women we found that four out of five subjects demonstrated EFL. When accounting for the effect of fitness, the incidence of EFL at maximal exercise is in good agreement with Guenette et al. (14) where the proportion of highly trained men and women who exhibit EFL is comparable. Beyond the aforementioned effect of fitness, the reasons for the between-subject variation in EFL are largely unclear, but our findings suggest that the onset of EFL is likely related to differences in airway size relative to lung size and by association with the magnitude of the dysanapsis ratio. Indeed, for a given V̇e an individual with large airways relative to their lung size is less likely to experience EFL than an individual with the same lung size but smaller conducting airways. Interestingly, the lone highly trained female subject who did not develop EFL had the largest dysanapsis ratio (0.24 au at a VC of 4.5), which was close to the male regression line. Moreover, Fig. 4 shows two men who are similar in age, height, and lung size, but the subject on the right (Fig. 4B) has a smaller dysanapsis ratio and presumably smaller airways. The subjects achieved a similar V̇o2 max and adopted comparable breathing patterns, but the subject in Fig. 4B had marked mechanical ventilatory constraints and a high Wb. Thus the effects of smaller airways can also be observed in men. It could be argued ventilatory constraints are best explained by smaller absolute airway diameter rather than biological sex. However, as we have shown above, women generally have smaller diameter airways relative to men. Therefore, the probable cause of ventilatory constraint during heavy exercise is smaller absolute airway size, which is most often present in women but can also be observed in some men.

Perspectives

We recognize that the correlative nature of our findings and relatively small sample size employed in this study limit the generalizability of its findings. However, our observations merit brief comment and we cautiously interpret our findings to mean the following. Owing to differences in airways, highly fit women will, on average, use a substantially greater proportion of their ventilatory reserve compared with equally trained men. However, there are notable exceptions where men can have a small dysanapsis ratio and women can have a large ratio with predictable effects on ventilatory constraint. Finally, we emphasize that while we have reported interaction between fitness (i.e., ventilatory demand) and airway size, many unresolved questions remain. For example, do smaller airways necessarily result in a higher O2 cost of breathing? We have recently reported that women have a higher O2 cost of breathing for a given level of ventilation, which represents a greater fraction of V̇o2 max (9), but the relationship with airway dimensions is unclear. Second, does our measure of dysanapsis ratio, as an index of airway size, correspond to true anatomical measures across multiple airway generations in men and women? Perhaps contemporary imaging methods such as optical coherence tomography (21) can be applied in future studies to specifically address the interrelationships among sex, human airway dimensions, and the pulmonary mechanics of exercise.

Conclusions.

We found that, on average, the higher Wb in women can be attributed to greater resistive work, which is indicative of inherently smaller diameter airways. Specifically, when VC is corrected for, women exhibit a smaller dysanapsis ratio, which is suggestive of smaller conducting airways. Furthermore, the smaller dysanapsis ratio is associated with a higher resistive Wb. Overall, smaller conducting airways appear to lead to increased mechanical ventilatory constraints and Wb in both men and women. However, women as a function of biological sex appear predisposed to have smaller airways and as such an increased Wb during exercise.

GRANTS

This study was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). P. B. Dominelli and Y. Molgat-Seon were supported NSERC postgraduate scholarships, and P. M. Swartz was supported by a NSERC undergraduate scholarship.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: P.B.D., Y.M.-S., G.E.F., and A.W.S. conception and design of research; P.B.D., Y.M.-S., G.E.F., and A.W.S. performed experiments; P.B.D., Y.M.-S., D.B., P.M.S., G.E.F., and A.W.S. analyzed data; P.B.D., Y.M.-S., D.B., P.M.S., J.D.R., G.E.F., and A.W.S. interpreted results of experiments; P.B.D., Y.M.-S., D.B., P.M.S., J.D.R., and A.W.S. prepared figures; P.B.D., Y.M.-S., D.B., P.M.S., J.D.R., G.E.F., and A.W.S. drafted manuscript; P.B.D., Y.M.-S., D.B., P.M.S., J.D.R., G.E.F., and A.W.S. edited and revised manuscript; P.B.D., Y.M.-S., D.B., P.M.S., J.D.R., G.E.F., and A.W.S. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Thoracic Society. Lung function testing: selection of reference values and interpretative strategies. American Thoracic Society. Am Rev Respir Dis 144: 1202–1218, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Thoracic Society. Standardization of Spirometry, 1994 Update American Thoracic Society. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 152: 1107–1136, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Babb TG, Beck KC, Johnson BD. Dysanapsis: importance of measured lung static recoil pressure. Med Sci Sports Exerc 44: 1194; author reply 1195, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Becklake MR, Kauffmann F. Gender differences in airway behaviour over the human life span. Thorax 54: 1119–1138, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colebatch HJ, Greaves IA, Ng CK. Exponential analysis of elastic recoil and aging in healthy males and females. J Appl Physiol 47: 683–691, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crapo RO, Morris AH, Clayton PD, Nixon CR. Lung volumes in healthy nonsmoking adults. Bull Eur Physiopath Respir 18: 419–425, 1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dominelli PB, Foster GE, Dominelli GS, Henderson WR, Koehle MS, McKenzie DC, Sheel AW. Exercise-induced arterial hypoxaemia and the mechanics of breathing in healthy young women. J Physiol 591: 3017–3034, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dominelli PB, Guenette JA, Wilkie SS, Foster GE, Sheel AW. Determinants of expiratory flow limitation in healthy women during exercise. Med Sci Sport Exerc 43: 1666–1674, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dominelli PB, Render JN, Molgat-Seon Y, Foster GE, Romer LM, Sheel AW. Oxygen cost of exercise hyperpnoea is greater in women compared with men. J Physiol 593: 1965–1979, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dominelli PB, Sheel AW. Experimental approaches to the study of the mechanics of breathing during exercise. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 180: 147–161, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green M, Mead J, Turner JM. Variability of maximum expiratory flow-volume curves. J Appl Physiol 37: 67–74, 1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guenette JA, Dominelli PB, Reeve SS, Durkin CM, Eves ND, Sheel AW. Effect of thoracic gas compression and bronchodilation on the assessment of expiratory flow limitation during exercise in healthy humans. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 170: 279–286, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guenette JA, Querido JS, Eves ND, Chua R, Sheel AW. Sex differences in the resistive and elastic work of breathing during exercise in endurance-trained athletes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 297: R166–R175, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guenette JA, Witt JD, McKenzie DC, Road JD, Sheel AW. Respiratory mechanics during exercise in endurance-trained men and women. J Physiol 581: 1309–1322, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hughes JM, Hoppin FG Jr, Mead J. Effect of lung inflation on bronchial length and diameter in excised lungs. J Appl Physiol 32: 25–35, 1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson BD, Saupe KW, Dempsey JA. Mechanical constraints on exercise hyperpnea in endurance athletes. J Appl Physiol 73: 874–886, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacNutt MJ, De Souza MJ, Tomczak SE, Homer JL, Sheel AW. Resting and exercise ventilatory chemosensitivity across the menstrual cycle. J Appl Physiol 112: 737–747, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin TR, Castile RG, Fredberg JJ, Wohl ME, Mead J. Airway size is related to sex but not lung size in normal adults. J Appl Physiol 63: 2042–2047, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McClaran SR, Harms CA, Pegelow DF, Dempsey JA. Smaller lungs in women affect exercise hyperpnea. J Appl Physiol 84: 1872–1881, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McClaran SR, Wetter TJ, Pegelow DF, Dempsey JA. Role of expiratory flow limitation in determining lung volumes and ventilation during exercise. J Appl Physiol 86: 1357–1366, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McLaughlin RA, Noble PB, Sampson DD. Optical coherence tomography in respiratory science and medicine: from airways to alveoli. Physiology 29: 369–380, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mead J. Dysanapsis in normal lungs assessed by the relationship between maximal flow, static recoil, and vital capacity. Am Rev Respir Dis 121: 339–342, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris JF, Koski A, Temple WP, Claremont A, Thomas DR. Fifteen-year interval spirometric evaluation of the Oregon predictive equations. Chest 93: 123–127, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Otis AB, Fenn WO, Rahn H. Mechanics of breathing in man. J Appl Physiol 2: 592–607, 1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patterson HD, Thompson R. Recovery of inter-block information when block sizes are unequal. Biometrika 58: 545, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. Thousand Oaks, NY: Sage, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rohrer F. Der strömungswiderstand in den menschlichen atemwegen und der einfluss der unregelmässigen verzweigung des bronchialsystems auf den atmungsverlauf in verschiedenen lungenbezirken. Pflügers Arch Ges Physiol 162: 225–299, 1915. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheel AW, Guenette JA. Mechanics of breathing during exercise in men and women: sex versus body size differences? Exerc Sport Sci Rev 36: 128–134, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheel AW, Guenette JA, Yuan R, Holy L, Mayo JR, McWilliams AM, Lam S, Coxson HO. Evidence for dysanapsis using computed tomographic imaging of the airways in older ex-smokers. J Appl Physiol 107: 1622–1628, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thurlbeck WM. Postnatal human lung growth. Thorax 37: 564–571, 1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Turner JM, Mead J, Wohl ME. Elasticity of human lungs in relation to age. J Appl Physiol 25: 664–671, 1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walls J, Maskrey M, Wood-Baker R, Stedman W. Exercise-induced oxyhaemoglobin desaturation, ventilatory limitation and lung diffusing capacity in women during and after exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol 87: 145–152, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wanke T, Formanek D, Schenz G, Popp W, Gatol H, Zwick H. Mechanical load on the ventilatory muscles during an incremental cycle ergometer test. Eur Respir J 4: 385–392, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]