Abstract

Psammomatous melanotic schwannoma (PMS) is a rare pigmented tumor that can be part of the Carney complex. Here, we describe the case of a 35-year-old female patient presenting an isolated subcutaneous PMS. Histopathological analysis could not formally exclude the malignant nature of the tumor. The challenging histological diagnosis and consequently the management of the patient are described.

Key Words: Psammomatous melanotic schwannoma, Psammoma bodies, Schwann cells, Melanoma

Background

Psammomatous melanotic schwannoma (PMS) is a very rare pigmented tumor composed of Schwann cells capable of melanogenesis. The histopathogenesis of this tumor is debatable considering the common neuroectodermal origin of melanocytes and Schwann cells [1]. PMS arises most frequently from the spinal nerve roots and sympathetic ganglia, but other primary sites such as visceral organs and skin have been reported [2]. In half of the cases, the tumor may occur within the Carney complex, or it can be isolated [3]. Although most of the cases follow a benign clinical course, some malignant variants with possible local relapses and metastases have been reported [2].

Methods

The totally excised tumor obtained from the patient for diagnostic purpose was fixed in formalin, embedded in paraffin, cut at 5 µm and stained with hematoxylin-eosin. An immunohistochemical study was performed with the avidin-biotin immunoperoxidase technique on deparaffinized sections using commercially available antibodies to Melan-A/MART-1, HMB45, CD34, CD117, cytokeratin, EMA, CD68 and S100.

Case Report

Here, we describe the case of an isolated PMS in a 35-year-old female patient localized on the buttocks, clinically simulating a pilonidal cyst. The tumor had been noticed by the patient since she was 12 years old and slowly increased in size during the 3 years before it was surgically removed. Histological examination showed circumscribed subcutaneous proliferation of spindle-shaped cells with rounded ovoid nuclei, frequent nuclear grooves and prominent intracytoplasmic melanin pigment. Mitoses were quite infrequent, and <1 mitosis per 10 fields of high magnification could be seen. Numerous psammoma bodies were seen without zones of necrosis (fig. 1). The spindle cells stained positive for S-100, Melan-A and HMB-45 (fig. 2) but were negative for CD34, CD117, cytokeratin, EMA and CD68. This morphological and immunohistochemical profile confirmed the diagnosis of PMS. No clinical evidence of any association with the Carney complex was present as assessed by full meticulous skin examination and cardiac echography in order to exclude intracardiac myxoma. The family history of the patient was positive for Graves’ disease, but no other endocrine disease was present. The malignant nature of the tumor could not be initially excluded based solely on the abovementioned morphology and the lack of significant mitotic activity. Therefore, the patient underwent additional skin excision with 1 cm margin, and a follow-up for high-risk malignant melanoma was initiated.

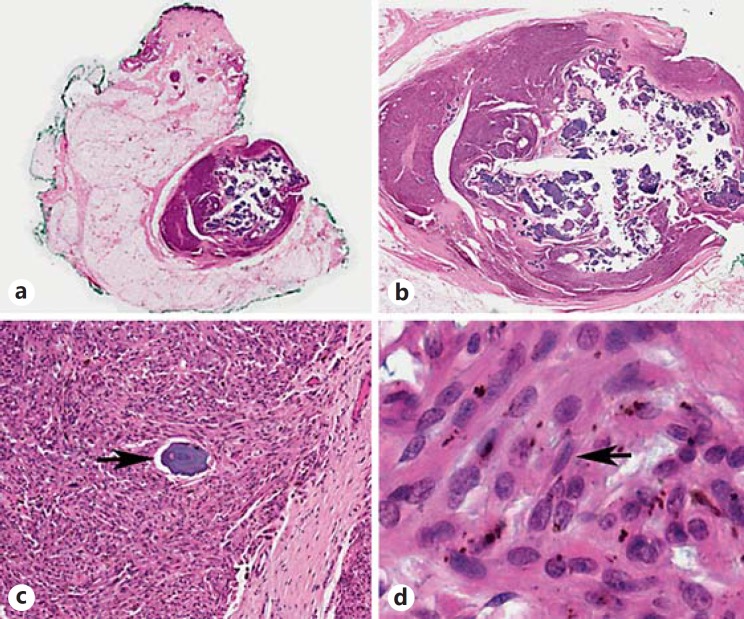

Fig. 1.

Well-circumscribed subcutaneous tumor (a, original magnification, ×0.2; b, original magnification, ×1) composed of spindle-shaped cells with frequent nuclear grooves (d, arrow; original magnification, ×82) and intracytoplasmic melanin pigment. Numerous psammoma bodies were present (c, arrow; original magnification, ×10).

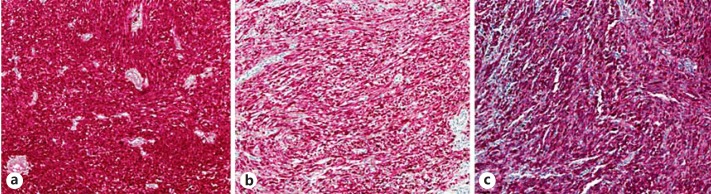

Fig. 2.

The tumor cells were positive for S100 (a), Melan-A (b) and HMB-45 (c). Original magnification, ×10.

Discussion

Unless occurring within an already recognized Carney complex, the diagnosis of PMS relies on histological examination [4]. The main histological differential diagnosis includes malignant melanoma, which shares common features such as melanin synthesis and positive staining for melanocytic markers. Predominantly spindled (rather than epithelioid-plasmacytoid) morphology, heavy melanin pigmentation, psammoma bodies, vacuolated (adipocyte-like) cells and striking nuclear pleomorphism with a relatively low mitotic rate suggest PMS [5].

To our knowledge, 20 cases of isolated cutaneous or subcutaneous PMS have been reported, with most cases being clinically described as a slow-growing cutaneous or subcutaneous mass in the upper parts of the body [6,7,8]. In our patient, the tumor did not occur within the Carney complex and was clinically considered as a pilonidal cyst both because of its location and its volume which had remained unchanged since childhood, but finally increased during the last 3 years before it was removed. Because of the clinical context and the uncertainty of the biological behavior of this rare tumor which can undergo malignant progression in about 10-35% of a limited number of cases [2,5], its malignant potential cannot be formally ruled out. Recently, some authors have even suggested that the malignant potential of melanotic schwannomas (with or without psammoma bodies) is underestimated [5]. Therefore, a careful follow-up for a potentially high-risk malignant tumor should be recommended.

Distinguishing PMS from malignant melanoma can be challenging for dermatopathologists who should be aware of this rare pigmented cutaneous tumor.

Statement of Ethics

The patient has given her informed consent for this publication.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest regarding this publication. No sponsorship or funding need to be declared.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor C. Fletcher from Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Mass., USA, for his critical opinion about the diagnosis.

References

- 1.Baroffio A, Dupin E, Le Dourin NM. Clone-forming ability and differentiation potential of migratory neural crest cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5325–5329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marton E, Feletti A, Orvieto E, Longatti P. Dumbbell-shaped C-2 psammomatous melanotic malignant schwannoma. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:591–599. doi: 10.3171/spi.2007.6.6.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carney J. Psammomatous melanotic schwannoma. A distinctive heritable tumor with special associations, including cardiac myxoma and the Cushing syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990;14:206–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurthkaya-Yapicier Ö, Scheithauer B, Woodruff JM. The pathobiologic spectrum of Schwannomas. Histol Histopathol. 2003;18:925–934. doi: 10.14670/HH-18.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torres-Mora J, Dry S, Li X, Binder S, Amin M, Folpe AL. Malignant melanotic schwannian tumor. A clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and gene expression profiling study of 40 cases, with a proposal for the reclassification of ‘melanotic schwannoma’. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:94–105. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182a0a150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaehler KC, Russo P, Katenkamp D, Kreusch T, Neuber K, Schwarz T, Hauschild A. Melanocytic schwannoma of the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues: three cases and a review of the literature. Melanoma Res. 2008;18:438–442. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e32831270d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Claessens N, Heymans O, Arrese JE, Garcia R, Oelbrandt B, Piérard GE. Cutaneous psammomatous melanotic schwannoma non-recurrence with surgical excision. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:799–802. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200304110-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monteagudo C, Ferrandez A, Gonzalez-Devesa M, Llombart-Bosch A. Psammomatous malignant melanoma arising in an intradermal naevus. Histopathology. 2001;39:493–497. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2001.01280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]