Abstract

A new nucleic acid detection method was developed for a rapid and cost-effective diagnosis of infectious disease. This approach relies on the three unique elements: (i) detection probes that regulate DNA polymerase activity in response to the complementary target DNA; (ii) universal reporters conjugated with a single fluorophore; and (iii) fluorescence polarization (FP) detection. As a proof-of-concept, the assay was used to detect and sub-type Salmonella bacteria with sensitivities down to a single bacterium in relatively short periods of time.

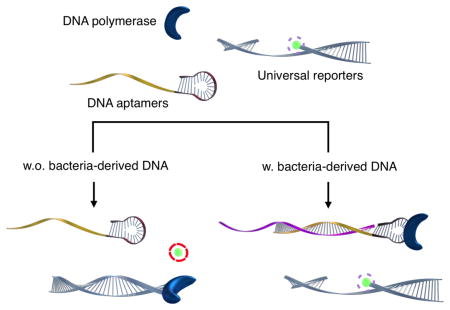

Graphical Abstract

A new fluorescence polarization method was developed to accurately detect and sub-type salmonella bacteria with sensitivities down to a single bacterium in relatively short periods of time.

The need for rapid and cost-effective methods for pathogen detection is increasing worldwide. This is in part due to the emergence of drug resistant pathogens, more virulent strains, the increasing costs of containment (e.g., Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, Ebola) and infections through community centers and hospitals.[1–3] With the advance of miniaturized PCR devices, [4] nucleic acid testing is gaining renewed interest as a promising tool for sensitive, specific infection diagnosis.[5–10] The most widely used assay format is the fluorescence-based detection, which measures either the PCR-product accumulation in real time or at the end of a given amplification reaction. The analytical signal can be generated by using intercalating dyes (e.g. SYBR green I) that become fluorescent when bound to double-stranded DNA.[11] The method is simple and cost-effective with a single reagent used for signal generation, but can be susceptible to false-positives (e.g., from primer-dimer formation). Alternatively, sequence-specific fluorescent probes (e.g., Taqman, Molecular beacon, LightCycler, and Scorpions probes) can be used to improve the accuracy.[12] This approach, however, requires separate, specialized probes (labeled fluorophore and quencher) for each nucleic acid target, thus increasing the assay cost.

We herein report on a new PCR-detection scheme that enables sequence-specific, cost-effective detection of pathogens. The method integrates three elements: (i) a detection probe that can regulate DNA polymerase activity in the presence of a complementary target DNA, [13–15] (ii) a universal DNA reporter conjugated with a single fluorophore, and (iii) fluorescence polarization (FP) detection. When hybridized with target oligonucleotides, the detection probe binds to and inactivates DNA polymerase. The fluorophore can then be retained in the reporter DNA, and the complex assumes slow diffusional rotation, which results in high FP values. In the absence of target oligonucleotides, on the other hand, uninhibited DNA polymerase can catalyze primer extension reactions, which cleaves fluorophore from the reporter probe. The free fluorophore can rotate rapidly to lose initial, uniform polarization, which results in low FP values. The developed approach has several advantages over conventional PCR detection: (i) the assay is simple and rapid without requiring washing steps; (ii) the separation of target recognition (a detection probe) and signal generation (a universal reporter) reduces the assay cost while maintaining high specificity; (iii) the FP detection, for its ratiometric nature, is robust against environmental noise (e.g., pH, photobleaching, temperature, opacity) and can be performed in a simple homogenous assay format.[16–20] As a proof-of-concept, we applied the FP assay to detect Salmonella bacteria. We achieved the detection sensitivity of ~1 CFU in blood samples, and were able to subtype different strains based on their genetic differences.

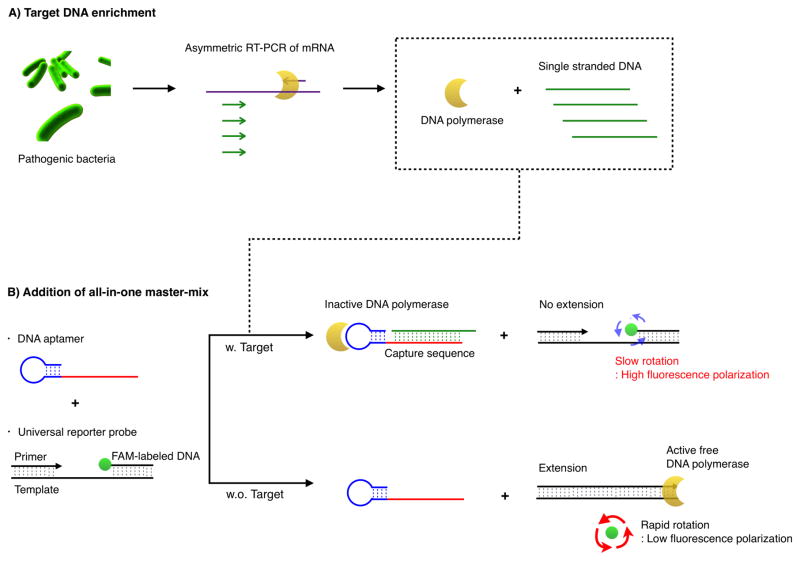

Scheme 1 illustrates the assay procedure for bacterial detection. We chose bacterial mRNA as the primary target, because multiple copies of mRNA per bacterium would increase the likelihood of detection. We first extracted total RNA from a specimen and amplified target mRNA via a asymmetric reverse transcription (RT-) PCR.[21] We next added the all-in-one master-mix containing detection and universal reporter probes. The DNA polymerase used in the RT-PCR retained its activity[22] and could be recycled for the extension reaction on the reporter probes. The entire process can thus be performed in a single tube without washing steps. The level of fluorescence polarization (FP) was measured following an incubation step at room temperature.

Scheme 1.

Schematic of the assay procedure to detect the pathogenic bacteria. (A) Total RNA is extracted from the sample and messenger RNA (mRNA) is amplified via asymmetric RT-PCR. The single-stranded DNAs are predominantly produced and DNA polymerase used in PCR amplification maintains its activity. (B) Single-stranded DNA of the amplified product is then incubated with the all-in-one master mix composed of detection and universal reporter probes. The resulting fluorescence polarization values are subsequently measured.

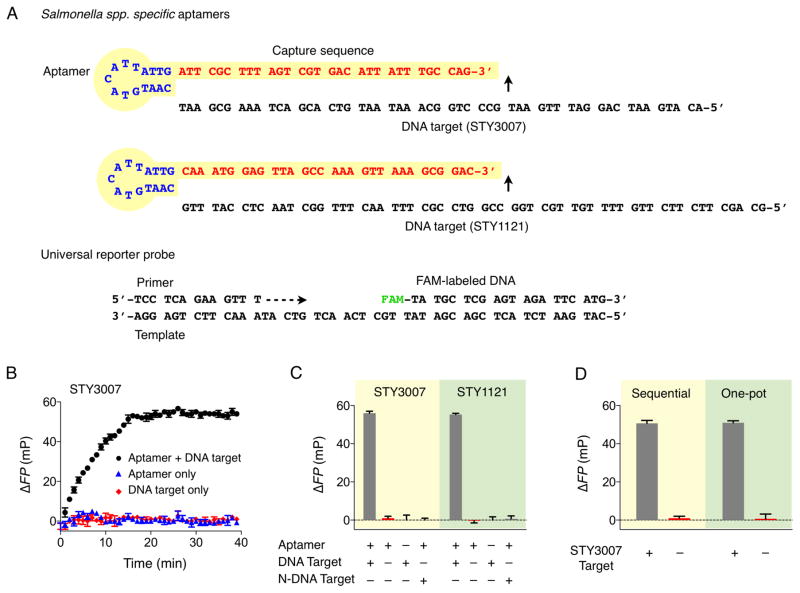

We applied the FP assay to detect Salmonella, one of the most common causes of food-borne diseases. We targeted specific gene regions (STY3007 and STY1121) conserved in Salmonella enterica species. The detection probes (pan-Salmonella detection probes) were designed to have a hairpin structure (aptamer for DNA polymerase)[14–15] joined by a single-stranded capture sequence (Figure 1A).[13] Although the length of the capture sequence has negligible effect on the polymerase-inhibition, [ 13] we determined to use 30-mer sequences to maximize the specificity for target Salmonella DNA. The designed probes showed no similarity to any other targets according to the BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Sequence Tool) search (Table S1 in Supporting Information). We also designed primers to flank the target sequences for hybridization. For the signal detection, fluorescein-labeled DNA, its primer and template were prepared, ensuring no sequence overlap with other targets (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Assay validation. A) Sequences of pan-Salmonella detection probes (STY3007 and STY1121) and universal reporter probe composed of primer, template, and FAM-labeled DNA. B) Kinetic measurement of the primer extension reaction. C) Validation of STY3007 and STY1121 detection probes for the specific detection of complementary target DNAs. High ΔFP was obtained only when both detection probe and the perfectly matched target DNA (200 nM) were present. N-DNA target indicates the non-complementary target DNA. The N-DNA was STY1121 target DNA for STY3007 detection; STY3007 target DNA for STY1121 detection. D) Variation of addition step of detection and universal reporter probe after PCR amplification. “Sequential” comprises the addition of detection probe (STY3007 detection probe) to PCR mixture containing the amplified product (STY3007 target), followed by the incubation with the universal detection probe. “One-pot” means the simultaneous addition of detection and universal reporter probe to PCR mixture containing the amplified product. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and the data are displayed as mean ± s.d.

We first used synthetic oligonucleotides to validate the assay. The kinetic measurement showed that the extension reaction reached a plateau 20 min after mixing detection probes and target oligonucleotides (STY3007; Figure 1B). We thus chose 20 min as the optimal extension. As an analytical signal, we defined the differential output ΔFP = FP – FP0, where FP0 is the fluorescence polarization of control samples containing DNA polymerase and the reporter probe only. The reaction was highly sequence-specific; we observed high ΔFP only in the presence of target oligonucleotides (Figure 1C). Electrophoretic band-shift analysis[23] confirmed that detection probes, in the presence of target oligonucleotides, complexed with DNA polymerase and limited its catalytic activity (Figure S1 in SI). We further compared two assay procedures, namely a sequential and a one-pot condition (see Methods for assay details). In the sequential assay, detection probes were first incubated with target DNA and polymerase, followed by the addition of universal reporter probes; in the one-pot assay, both detection and reporter probes were mixed together with target DNA and polymerase. The observed ΔFP values (Figure 1D) were statistically identical (two-tailed t-test, P > 0.76), [24] which demonstrated that PCR amplification was compatible with our detection system. The one-pot reaction was possible due to the favorable reaction kinetics: DNA hybridization has a dissociation constant in low picomolar ranges, [25] whereas DNA polymerase binds to a primer-template DNA with a dissociation constant in sub-micromolar ranges.[26] Therefore, the hybridization between the detection probe and a complementary target DNA occurs faster than the binding of DNA polymerase to a universal reporter probe. This is effectively the same reaction order in the sequential assay wherein the target DNA and the detection probe are mixed first, followed by the addition of the universal probe. We opted for the one-pot scheme, as it speeds up the assay time and is better suited for point-of-care applications.

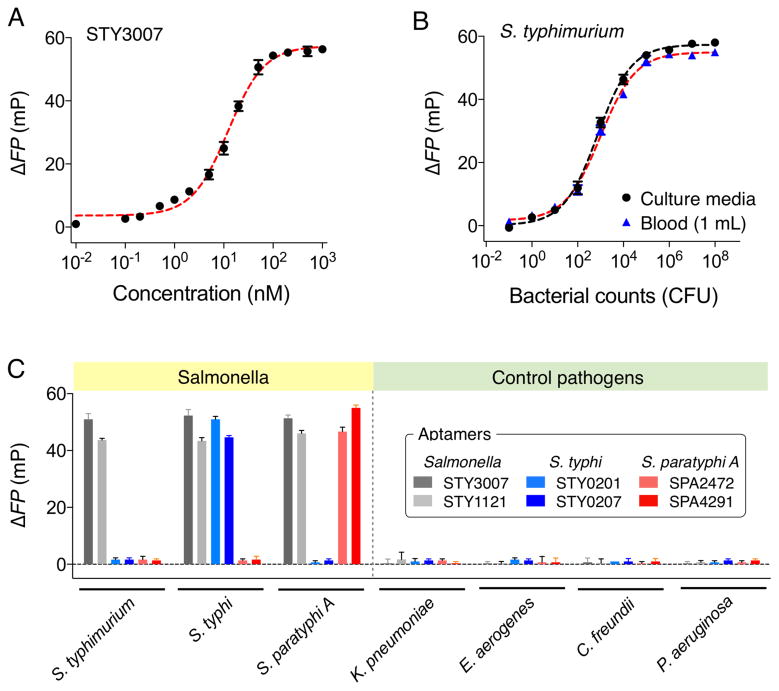

We next determined the detection sensitivity of the FP assay. With synthetic oligonucleotides as a target, the absolute detection limit (without PCR) was determined to be ~0.5 nM, which is comparable to or lower than those of nucleic acid-based diagnostic platforms (Figure 2A).[13, 27–29] Such high sensitivity enabled bacterial detection at the single colony-forming unit (CFU) level. For example, we prepared bacterial samples through the serial dilution of Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium (S. Typhimurium) in culture media. Following mRNA extraction and asymmetric RT-PCR (40 cycles), we added STY3007-detection and reporter probes. The measured ΔFP signal showed CFU-dependent changes with the limit of detection (LOD) of ~1 CFU/ml (Figure 2B). We further spiked S. Typhimurium in human blood. The assay was robust, yielding similar results as in the culture media samples. The estimated LOD was ~1 CFU/mL in the whole blood (see Experimental section for details).

Figure 2.

Detection of Salmonella bacteria with fluorescence polarization system. (A) The absolute detection limit of STY3007 synthetic target DNA without PCR amplification, which was ~0.5 nM. (B) Detection of S. Typhimurium in culture media and human blood (1 mL). The detection of S. Typhimurium in human blood was achieved by spiking serial dilutions of S. Typhimurium into human blood. The detection limit was a single bacterium. (C) Selective detection and accurate sub-typing of Salmonella strains (106 CFU). Four different pathogens (106 CFU) were included as controls. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and the data are displayed as mean ± s.d.

We next extended the FP assay to differentiate Salmonella serotypes.[30] We targeted Salmonella serotypes (S. Typhi and S. Paratyphi A) that are restricted to humans and the primary cause of enteric fever (Table S2 in Supporting Information).[31] For each serotype, we selected two target sequences that were highly expressed[32, 33]: STY0201, STY0207 for S. Typhi; SPA2472, SPA4291 for S. Paratyphi A. Corresponding DNA detection probes were then designed (Table S1 in SI). The profiling experiment showed excellent selectivity of the developed assay (Figure 2C). The ΔFP signals from other pathogenic bacteria samples (i.e., Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter aerogenes, Citrobacter freundii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa) were negligible for Salmonella-related probes even at high bacterial load (106 CFU/mL). Pan-Salmonella detection probes (STY3007, STY1121), however, reported high signals for all Salmonella serotypes; the serotype-specific probes then identified intended targets with high selectivity.

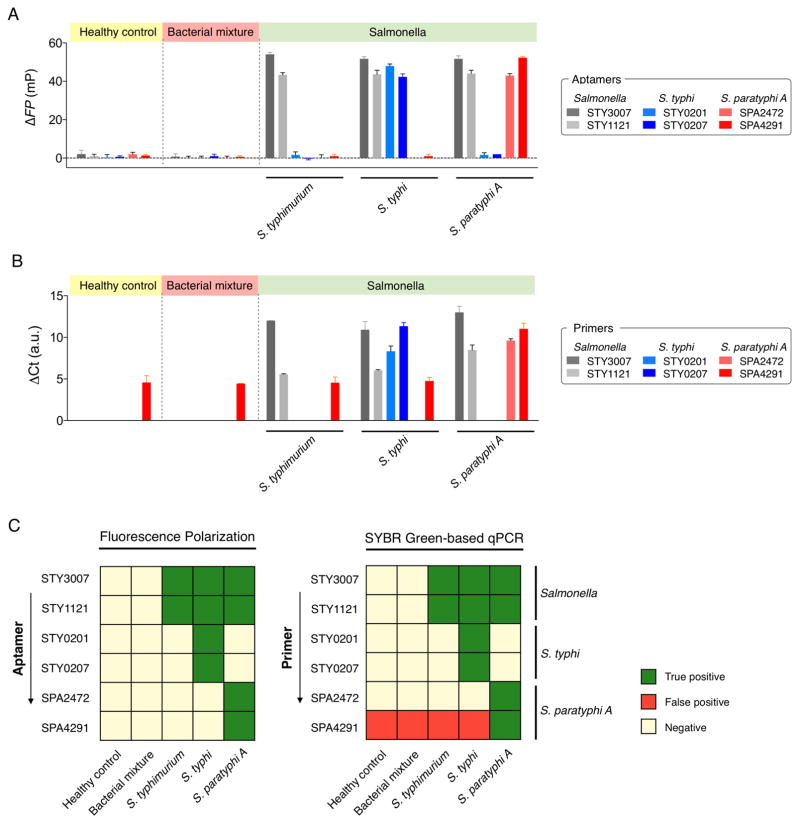

We also evaluated FP assay’s potential for high-throughput Salmonella screening. We prepared blood samples, mimicking healthy condition, Salmonella infection, and other bacteremia. Total RNA was extracted from the blood sample (1 mL), transcribed to cDNA, and aliquoted. Each aliquot (2.5 μL cDNA) was then tested for a different probe: pan-Salmonella (STY3007, STY1121), S. Typhi (STY0201, STY0207), S. Paratyphi A (SPA2472, SPA4291). The FP assay showed high detection accuracy and produced a robust signal even at the presence of abundant human genomic nucleic acids (Figure 3A and C). Conventional qPCR, on the other hand, yielded false-positives (Figure 3B and C) that were likely due to the primer-dimer formation. Further analysis showed (Table S3 in SI) that the melting temperature of non-targeted PCR products (false-positives) was similar to that of the targeted ones (true-positive samples), suggesting the generation of spurious by-products. The FP assay was robust against external factors (e.g., primer-dimer formation) and could achieve the sequence-specific detection with reduced assay cost (Table S4 in SI).

Figure 3.

Salmonella detection in human blood. (A) Detection of Salmonella bacteria with fluorescence polarization system. (B) Real-time PCR quantification using SYBR Green. (C) Heat maps showing the specificity of fluorescence polarization system and qPCR. Five different samples that mimic clinical scenarios were prepared, which includes healthy control, patients infected with the bacterial mixture (K. pneumoniae, E. aerogenes, C. freundii, and P. aeruginosa, 106 CFU/mL), S. Typhimurium, S. Typhi, and S. Paratyphi A (106 CFU/mL). All experiments were performed in triplicate, and the data are displayed as mean ± s.d.

In summary, we have developed a new detection approach to nucleic acid tests, which uses (i) a targetspecific detection probe to modulate DNA polymerase activity and (ii) a universal reporter for signal generation. The assay is simple, modular, and cost-effective (see Table S4 in SI for comparison with other modalities). It is complete in less than 20 min at room temperature without washing steps (one-pot reaction) after the completion of PCR, and the same universal reporter can be used for different DNA targets. The FP assay’s performance is comparable to that of Taqman assay, and its cost is much lower and favorable for multi-target detection (~$1 for 100 targets, Table S4 in SI). When applied to Salmonella in blood, the developed assay achieved high sensitivity (~1 CFU/mL) and could differentiate S. Typhi and S. Paratyphi A. In combination with miniaturized PCR and optical detectors, [4] this assay could be a powerful platform for point-of-care pathogen detection. With judicious probe design, [27] it is also conceivable to adopt the assay to detect single-nucleotide mismatch.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH Grants R01HL113156, R01EB004626, R01EB010011, HHSN268201000044C and R33100023; DoD OCRP Award W81XWH-14-1-0279; Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education (2014R1A6A3A03059728).

References

- 1.Yang SJ, Park KY, Seo KS, Besser TE, Yoo HS, Noh KM, Kim SH, Kim SH, Lee BK, Kook YH, Park YH. J Vet Sci. 2001;2:181–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith KF, Goldberg M, Rosenthal S, Carlson L, Chen J, Chen C, Ramachandran S. J R Soc Interface. 2014;11:20140950. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2014.0950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peleg AY, Hooper DC. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1804–1813. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0904124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marx V. Nat Methods. 2015;12:393–397. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dark PM, Dean P, Warhurst G. Crit Care. 2009;13:217. doi: 10.1186/cc7886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pechorsky A, Nitzan Y, Lazarovitch T. J Microbiol Methods. 2009;78:325–330. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ottesen EA, Hong JW, Quake SR, Leadbetter JR. Science. 2006;314:1464–1467. doi: 10.1126/science.1131370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loman NJ, Constantinidou C, Chan JZ, Halachev M, Sergeant M, Penn CW, Robinson ER, Pallen MJ. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10:599–606. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hahn S, Mergenthaler S, Zimmermann B, Holzgreve W. Bioelectrochemistry. 2005;67:151–154. doi: 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hans R, Marwaha N. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2014;8:2–3. doi: 10.4103/0973-6247.126679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonetta L. Nat Methods. 2005;2:305–312. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Espy MJ, Uhl JR, Sloan LM, Buckwalter SP, Jones MF, Vetter EA, Yao JDC, Wengenack NL, Rosenblatt JE, Cockerill FR. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:165–256. doi: 10.1128/CMR.19.1.165-256.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park KS, Lee CY, Park HG. Chem Commun. 2015;51:9942–9945. doi: 10.1039/c5cc02060c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dang C, Jayasena SD. J Mol Biol. 1996;264:268–278. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin Y, Jayasena SD. J Mol Biol. 1997;271:100–111. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Latif S, Bauer-Sardina I, Ranade K, Livak KJ, Kwok PY. Genome Res. 2001;11:436–440. doi: 10.1101/gr.156601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen X, Levine L, Kwok PY. Genome Res. 1999;9:492–498. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ye BC, Yin BC. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:8386–8389. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang D, Fu R, Zhao Q, Rong H, Wang H. Anal Chem. 2015;87:4903–4909. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b00479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dubach JM, Vinegoni C, Mazitschek R, Fumene Feruglio P, Cameron LA, Weissleder R. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3946. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chung HJ, Castro CM, Im H, Lee H, Weissleder R. Nat Nanotechnol. 2013;8:369–375. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawyer FC, Stoffel S, Saiki RK, Chang SY, Landre PA, Abramson RD, Gelfand DH. PCR Methods Appl. 1993;2:275–287. doi: 10.1101/gr.2.4.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dittmer WU, Reuter A, Simmel FC. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:3550–3553. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Differences between these two cases were assessed using a two-tailed t-test, and a P value smaller than 0.05 was considered significant.

- 25.Wilkins Stevens P, Henry MR, Kelso DM. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:1719–1727. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.7.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Datta K, LiCata VJ. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:5590–5597. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liong M, Hoang AN, Chung J, Gural N, Ford CB, Min C, Shah RR, Ahmad R, Fernandez-Suarez M, Fortune SM, Toner M, Lee H, Weissleder R. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1752. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang PJ, Liu J. Anal Chem. 2012;84:4192–4198. doi: 10.1021/ac300778s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu CH, Li J, Liu JJ, Yang HH, Chen X, Chen GN. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:4889–4894. doi: 10.1002/chem.200903071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wattiau P, Boland C, Bertrand S. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:7877–7885. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05527-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charles RC, Liang L, Khanam F, Sayeed MA, Hung C, Leung DT, Baker S, Ludwig A, Harris JB, Larocque RC, Calderwood SB, Qadri F, Felgner PL, Ryan ET. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2014;21:280–285. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00661-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheikh A, Charles RC, Rollins SM, Harris JB, Bhuiyan MS, Khanam F, Bukka A, Kalsy A, Porwollik S, Brooks WA, LaRocque RC, Hohmann EL, Cravioto A, Logvinenko T, Calderwood SB, McClelland M, Graham JE, Qadri F, Ryan ET. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e908. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sheikh A, Charles RC, Sharmeen N, Rollins SM, Harris JB, Bhuiyan MS, Arifuzzaman M, Khanam F, Bukka A, Kalsy A, Porwollik S, Leung DT, Brooks WA, LaRocque RC, Hohmann EL, Cravioto A, Logvinenko T, Calderwood SB, McClelland M, Graham JE, Qadri F, Ryan ET. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1419. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.