Abstract

Background

Heart failure involves myocardial fibrosis and dysregulated angiogenesis.

Objective

We explored whether biomarkers of fibrosis and angiogenesis correlate with HF severity.

Methods

Biomarkers of fibrosis [Procollagen Types I and III(PIP, P3NP), carboxyterminal-telopeptide of Type-I collagen(ICTP), matrix metalloproteases (MMP2, MMP9), tissue inhibitor of MMP1 (TIMP1)]; and angiogenesis [placental growth factor(PGF), vascular endothelial growth factor(VEGF), soluble Fms-Like Tyrosine Kinase-1(sFlt1)] were measured in 52 HF patients and 19 controls.

Results

P3NP, ICTP, MMP2, TIMP1, PGF and sFlt1 levels were elevated in HF, while PIP/ICTP, PGF/sFlt1, and VEGF/sFlt1 ratios were reduced. PIP/ICTP, MMP-9/TIMP1 and VEGF/sFlt1 ratios were lowest among patients with severe HF.

Conclusions

Severe HF is associated with collagen breakdown and reduced angiogenesis. A multimarker approach may guide therapeutic targeting of fibrosis and angiogenesis in HF.

Introduction

Heart failure is a major cause of morbidity and mortality that affects >24 million individuals worldwide (Cowie et al., 1997; Davies et al., 2001; Go et al., 2014). Substantial resources are devoted to care for HF patients and to search for novel therapies to improve poor outcomes in these patients (Go et al., 2014). HF is defined by cardiac dysfunction associated with myocardial fibrosis and more recently, an imbalance between angiogenesis and cardiac hypertrophy is increasingly appreciated as an additional contributing mechanism (Lip and Chung, 2005). There is considerable interest in identifying circulating biomarkers of HF that may be used to select and monitor therapy in this rapidly growing patient population (Januzzi and Felker, 2013).

Progressive myocardial fibrosis in response to injury via myocyte replacement or diffuse deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) is a hallmark of pathological cardiac remodeling. The cardiac ECM consists mostly of type I collagen (80%) and type III collagen (10%). ECM turnover is determined by the net balance of collagen synthesis and degradation (Lopez et al., 2010). The synthesis of type I and type III collagen are heralded by the release into the circulation of procollagen type I C-peptide (PIP) and procollagen type III C-peptide (P3NP) respectively. The carboxyterminal telopeptide of type I collagen (ICTP) is released upon degradation of type I collagen (Lopez et al., 2010). The ratio of PIP to ICTP correlates with the severity of histological fibrosis in animal models and humans with hypertensive heart disease (Diez et al., 1996; Diez et al., 2002). Further, the PIP/ICTP ratio is elevated in some patients with dilated cardiomyopathy and regresses after treatment with aldosterone antagonists (Izawa et al., 2005). These studies suggest an elevated PIP/ICTP ratio reflects net collagen synthesis. P3NP is elevated in patients with advanced HF, a marker of poor prognosis, and reduced following treatment with aldosterone antagonists (Iraqi et al., 2009; Kaye et al., 2013; Klappacher et al., 1995; Zannad et al., 2000). Collagen is degraded by matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) which in turn are negatively regulated by tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP). Circulating levels of MMP2, MMP9 and TIMP1 are also elevated in chronic HF (Frantz et al., 2008; George et al., 2005; Zannad et al., 2000). These findings indicate that in patients with HF, matrix metabolism can be assessed by measurement of circulating markers and may reflect the progression of cardiac fibrosis.

The vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) family of pro-angiogenic growth factors includes the VEGFs and placental growth factor (PGF). These growth factors are expressed in multiple cell types in the heart including endothelial cells and contribute to vascular remodeling and myocardial angiogenesis (Abraham et al., 2000; Carmeliet, 2005; Izumiya et al., 2006). While many other factors also contribute to angiogenesis, aberrant vascular growth factor signaling has been implicated in cardiovascular diseases including pathological cardiac remodeling that leads to HF (Kodama et al., 2006; Luttun et al., 2002; Pilarczyk et al., 2008). The fms-like tyrosine kinase receptor-1 (Flt-1), or VEGF receptor-1, mediates many of the functions of the pro-angiogenic factors VEGF-A, VEGF-B and PGF. A soluble circulating form of Flt-1 is generated by proteolytic cleavage or alternative splicing in response to hypoxia (Nagamatsu et al., 2004; Parenti et al., 2002; Rahimi et al., 2009). Elevated levels of sFlt-1 have been observed in conditions of vascular perturbation such as acute coronary occlusion, acute HF due to myocardial infarction, pre-eclampsia, and sepsis (Kapur et al., 2011; Levine et al., 2006; Onoue et al., 2009; Yano et al., 2006). In chronic HF, higher sFlt-1 levels have been associated with adverse outcomes and provide incremental prognostic value to brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) measurement alone (Izumiya et al., 2006; Ky et al., 2011). PGF and VEGF levels are increased and positively associated with New York Heart Association (NYHA) class in chronic ischemic but not non-ischemic disease (Nakamura et al., 2009). Similarly, myocardial and circulating VEGF-A levels are increased in ischemic cardiomyopathy (ICM) relative to dilated cardiomyopathy (Abraham et al., 2000; Valgimigli et al., 2004). Taken together, these studies suggest a role for aberrant vascular homeostasis and angiogenesis in HF.

Recent evidence suggests angiogenic and fibrotic signaling pathways may be interrelated during the process of cardiac remodeling and are regulated by common factors. Aldosterone is a key mediator of cardiac and vascular remodeling. Drugs that inhibit the mineralocorticoid receptor (the receptor for aldosterone) significantly improve outcomes in clinical trials of HF with reduced ejection fraction (Pitt et al., 2003; Pitt et al., 1999; Zannad et al., 2011). Vascular mineralcorticoid receptors regulate expression of PGF and Flt-1 in mouse and human vessels and genetic ablation of PGF or blockade of Flt-1 attenuates aldosterone mediated vascular injury in mice (Jaffe et al., 2010; Pruthi et al., 2014). Transforming growth factor beta (TGFb) is a pro-fibrogenic cytokine implicated in the progressive myocardial fibrosis observed in heart failure (Leask, 2010). Selective myocyte knockdown of the receptor for TGFb in a mouse model of HF normalized myocardial capillarity in addition to blunting interstitial fibrosis (Koitabashi et al., 2011). Further substantiation of a connection between angiogenesis and fibrosis could have profound implications for therapeutic strategies for HF.

While the circulating milieu of patients with HF has been described for single markers or selected markers in a single physiological pathway, few studies have simultaneously examined circulating markers of angiogenesis and fibrosis. Investigation of multiple markers in tandem may yield additional information regarding angiogenesis and matrix metabolism in heart failure (Zannad, 2014). Furthermore, a multimarker approach may guide patient selection for guideline directed medical therapy for HF management (Yancy et al., 2013). Thus, the purpose of this study is to measure in parallel circulating markers of fibrosis and matrix remodeling and select circulating angiogenesis markers in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction.

Methods

Patients

A prospective study of 52 consecutive patients referred for cardiac catheterization to evaluate suspected LV dysfunction at Tufts Medical Center (Boston, Massachusetts) was performed. Exclusion criteria were cardiogenic shock, inotrope use, presence of a ventricular assist device, age <18 years old, acute coronary syndrome, pregnancy, active or history of malignancy, renal failure (estimated glomerular filtration rate <= 30 ml/min/1.73 m2), liver transaminase elevation >=2 times the upper limit of normal, non-sinus rhythm, or perceived interference with standard clinical care. All patients were clinically stable on oral therapy. The Institutional Review Board of Tufts Medical Center approved the study and all patients provided written informed consent.

Sample collection and preparation

Blood was collected at the time of arterial sheath insertion prior to catheterization. 19 healthy volunteers between the age of 21 and 80 years old without significant medical history or current medication use served as normal controls. Blood was collected from controls as a single lab draw at the Tufts Medical Center clinical research center. The blood samples were collected, allowed to clot for 30 minutes, centrifuged at 2,000 g for 15 minutes and stored at −80 °C prior to analysis. The samples were processed in duplicate for TGFB1, PIP, P3NP, ICTP, MMP2, MMP9, TIMP1, PGF, VEGF, sFlt1 levels using commercially available quantitative enzyme immunoassay kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions (TGF-beta 1, MMP2, MMP9, TIMP1, PGF, VEGF and sFlt1: R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN; PIP, P3NP and ICTP: Orion Diagnostica, Finland). Aldosterone levels were measured by COAT-A-COUNT Aldosterone Radioimmunoassay (Diagnostic Products Corporation, Los Angeles, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The intra-assay coefficients of variation were all less than 10%.

Statistics

The results of the serum measurements are expressed as mean +/− SD. Statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism version 6 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Continuous variables were compared by unpaired student’s T test and categorical variables were compared by Fischer’s exact test. The correlation between markers was assessed by scatterplots and unweighted Spearman coefficients. P values <0.05 were accepted as significant.

Results

Multimarker profile of HF patients compared to healthy controls

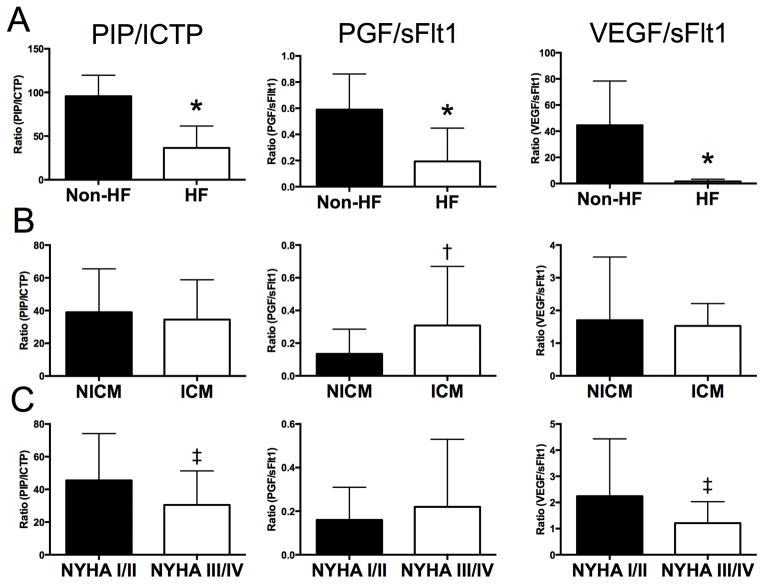

Averaged circulating levels of the fibrotic and angiogenic markers measured in 52 patients with HF and 19 controls without risk factors for cardiovascular disease are shown in Table 1. Compared to the HF patients, the controls did not differ in age, gender or race (all comparisons p>0.05). P3NP and ICTP were elevated in HF patients while PIP was similar between the groups resulting in a reduced PIP/ICTP ratio. PGF and sFlt1 were significantly increased among HF patients with similar levels of VEGF leading to reduced PGF/sFlt1 and VEGF/sFlt1 ratios. Taken together, the multimarker profile of HF patients compared to normal controls is consistent with fibrotic degradation and anti-angiogenesis (Figure 1A). Although substantial variability has been observed in the prior literature for individual marker measurements in HF, these findings are generally concordant with prior studies (Frantz et al., 2008; George et al., 2005; Kaye et al., 2013). We hypothesized that these fibrotic and angiogenic biomarkers might be linked due to regulation by aldosterone or TGFB. However, the correlation coefficients for aldosterone and TGFB levels with each of the other biomarkers was <0.4 indicating weak, if any correlation. Since there are differences between the control and HF populations in terms of sample collection and likely also comorbidities, all further analysis focused on comparisons within the HF patients.

Table 1.

Circulating profile of patients with heart failure and normal controls

| Normal (n=19) | HF (n=52) | P values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age | 60±10 | 57±15 | 0.296 |

| Male gender (%, n) | 63 (12) | 77 (40) | 0.364 |

| Caucasian Ethnicity (%, n) | 84 (16) | 87 (45) | 1 |

| Marker | |||

| BNP (ng/ml) | 2.6±0.9 | 14.4±7.7* | <0.001 |

| Aldosterone (pg/ml) | 112.2±59.4 | 294.1±372.5 | 0.043 |

| TGFB1 (pg/ml) | 122±45.1 | 136.9±57.7 | 0.313 |

| P3NP (ng/ml) | 3±0.9 | 9.8±5.8* | <0.001 |

| PIP (ng/ml) | 205.3±55.3 | 201±73.7 | 0.815 |

| ICTP (ng/ml) | 2±0.4 | 7.9±7.3* | <0.001 |

| PIP/ICTP | 95.7±24 | 36.5±25.1* | <0.001 |

| MMP2 (ng/ml) | 33.7±7.3 | 43.2±13.3* | <0.001 |

| MMP9 (ng/ml) | 60.3±26.3 | 51.7±28.1 | 0.248 |

| TIMP1 (ng/ml) | 10.1±1.4 | 15.5±5.2* | <0.001 |

| MMP2/TIMP | 3.4±0.8 | 2.9±0.9* | 0.043 |

| MMP9/TIMP | 6.5±3.3 | 3.8±2.6* | <0.001 |

| PGF (pg/ml) | 6.7±3 | 56.5±81* | 0.01 |

| VEGF (pg/ml) | 511±350 | 468.4±462 | 0.717 |

| sFlt1 (pg/ml) | 11.8±1.6 | 365.3±259.7* | <0.001 |

| PGF/sFlt1 | 0.59±0.27 | 0.19±0.25* | <0.001 |

| VEGF/sFlt1 | 44.5±33.9 | 1.6±1.6* | <0.001 |

P<0.05:

Normal vs. Heart Failure

Figure 1. Summary of fibrotic and angiogenic circulating multimarker profile in subjects with heart failure and normal controls.

The PIP/ICTP, PGF/sFlt1 and VEGF/sFlt1 ratios are compared among subjects with (A) heart failure (Zannad et al.) and without HF (non-HF), (B) patients with non-ischemic cardiomyopathy (NICM) and ischemic cardiomyopathy (ICM), and (C) patients with New York Heart Association (NYHA) class I/II and III/IV severity of heart failure. *, p<0.01, Non-HF vs HF; †, p<0.01; NICM vs. ICM; ‡, p<0.01; NYHA class I/II vs. III/IV HF

Multimarker profile of non-ischemic compared to ischemic cardiomyophathy

The HF patients were stratified by the etiology of cardiomyopathy into non-ischemic (NICM; n=35) or ischemic (ICM; n=17) and the clinical characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 2. The patients with NICM were younger and more likely to be female. Left ventricular ejection fraction (23±9 in ICM vs. 29±13 in NICM, p=0.078) and mean pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (22±5 in ICM vs. 19±5 in NICM, p=0.063) were not significantly different between the groups. As expected, prior myocardial infarction and antiplatelet therapy (aspirin and thienopyridine) were more common in the ICM group while other past medical history was similar between the groups. The circulating marker profile stratified by etiology of heart failure is presented in Table 3. Trends toward higher levels of PIP (226.4±85.4 in ICM vs. 188.6±65 in NICM, p=0.083) and P3NP (12±5.2 in ICM vs. 8.7±5.8 in NICM, p=0.067) were observed among patients with ICM. Compared to patients with ICM, patients with NICM had lower levels of ICTP, MMP2, MMP9, and PGF. The MMP2/TIMP1, MMP9/TIMP1 and PGF/sFlt1 ratios were therefore significantly lower in the NICM group. These findings are consistent with less angiogenesis and matrix remodeling in patients with NICM (Figure 1B).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of patients with heart failure stratified by etiology

| Ischemic CM (n=17) | Non-ischemic CM (n=35) | P values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Age | 63±10 | 53±16* | 0.026 |

| Male gender (%, n) | 94 (16) | 60 (21)* | 0.011 |

| LV ejection fraction (%, n) | 23±9 | 29±13 | 0.078 |

| Mean PCWP (mmHg) | 22±5 | 19±5 | 0.063 |

| Past medical history (%, n) | |||

| Hypertension | 71 (12) | 46 (16) | 0.139 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 71 (12) | 43 (15) | 0.079 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 35 (6) | 20 (7) | 0.309 |

| Active tobacco use | 0 (0) | 17 (6) | 0.161 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 76 (13) | 3 (1)* | <0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 6 (1) | 3 (1) | 1 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 18 (3) | 6 (2) | 0.315 |

| Medications (%, n) | |||

| Aspirin | 76 (13) | 40 (14)* | 0.019 |

| Thienopyridine | 35 (6) | 0 (0)* | <0.001 |

| Beta blocker | 65 (11) | 43 (15) | 0.237 |

| ACE inhibitor | 53 (9) | 34 (12) | 0.238 |

| Angiotensin II receptor blocker | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | 1 |

| Aldosterone antagonist | 18 (3) | 17 (6) | 1 |

| Diuretic | 65 (11) | 54 (19) | 0.558 |

| Lipid lowering agent | 71 (12) | 40 (14) | 0.075 |

P<0.05:

Ischemic vs. Non-ischemic cardiomyopathy

PCWP; Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure. ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme.

Table 3.

Circulating profile of patients with heart failure stratified by etiology

| Marker | Ischemic CM (n=17) | Non ischemic CM (n=35) | P values |

|---|---|---|---|

| BNP (ng/ml) | 15.2±6.6 | 14±8.2 | 0.596 |

| Aldosterone (pg/ml) | 373.1±282.4 | 255.7±407.4 | 0.291 |

| TGFB1 (pg/ml) | 136.7±49.6 | 137±62 | 0.985 |

| P3NP (ng/ml) | 12±5.2 | 8.7±5.8 | 0.067 |

| PIP (ng/ml) | 226.4±85.4 | 188.6±65 | 0.083 |

| ICTP (ng/ml) | 11.1±9.3 | 6.3±5.5* | 0.026 |

| PIP/ICTP | 31.6±22 | 39±26.5 | 0.329 |

| MMP2 (ng/ml) | 51.6±12.6 | 39.1±11.7* | <0.001 |

| MMP9 (ng/ml) | 62.1±27.1 | 46.6±27.6 | 0.062 |

| TIMP1 (ng/ml) | 14.3±5.2 | 16.1±5.3 | 0.253 |

| MMP2/TIMP | 3.7±0.9 | 2.5±0.6* | <0.001 |

| MMP9/TIMP | 4.8±3 | 3.3±2.3* | 0.043 |

| PGF (pg/ml) | 92.4±122.6 | 38.1±38.6* | 0.023 |

| VEGF (pg/ml) | 427.5±210.7 | 489.5±550.7 | 0.657 |

| sFlt1 (pg/ml) | 326.1±172.6 | 385.5±295.2 | 0.448 |

| PGF/sFlt1 | 0.31±0.36 | 0.13±0.15* | 0.02 |

| VEGF/sFlt1 | 1.53±0.68 | 1.7±1.93 | 0.72 |

P<0.05:

Ischemic vs. Non-Ischemic Cardiomyopathy

Multimarker profile of symptomatic compared to mild or asymptomatic HF

The circulating multimarker profile was further stratified by severity of symptoms.. Medical therapy for mild HF (NYHA class I/II) was compared to severe HF (NYHA class III/IV) and ACE inhibitor use was more frequent among NYHA III/IV patients (Table 4). As shown in Table 5, compared to NYHA class I/II HF patients, aldosterone, ICTP and MMP2 were higher in NYHA class III/IV HF patients. The PIP/ICTP, MMP-9/TIMP1 and VEGF/sFlt1 ratios were lower in patients with more symptomatic NYHA III/IV HF. This data indicates the circulating multimarker profile in severe symptomatic HF is consistent with enhanced fibrotic degradation and reduced angiogenesis compared to mild symptoms (Figure 1C).

Table 4.

Medical therapy of patients with heart failure stratified by NYHA functional class

| All HF pts (n=52) | NYHA class I/II (n=21) | NYHA class III/IV (n=31) | P values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin | 52 (27) | 45 (14) | 62 (13) | 0.27 |

| Thienopyridine | 12 (6) | 10 (3) | 14 (3) | 0.675 |

| Beta blocker | 50 (26) | 39 (12) | 67 (14) | 0.089 |

| ACE inhibitor | 40 (21) | 26 (8) | 62 (13)* | 0.02 |

| Angiotensin II receptor blocker | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 5 (1) | 0.404 |

| Aldosterone antagonist | 17 (9) | 19 (6) | 14 (3) | 0.724 |

| Diuretic | 58 (30) | 48 (15) | 71 (15) | 0.153 |

| Lipid lowering agent | 50 (26) | 48 (15) | 52 (11) | 1 |

P<0.05:

NYHA class I/II versus class III/IV

Table 5.

Circulating profile of patients with heart failure stratified by NYHA functional class

| Marker | NYHA class I/II (n=21) | NYHA class III/IV (n=31) | P values |

|---|---|---|---|

| BNP (ng/ml) | 14±6.6 | 14.7±8.4 | 0.742 |

| Aldosterone (pg/ml) | 140±106.2 | 376.4±459.3* | 0.025 |

| TGFB1 (pg/ml) | 134.6±50.5 | 138.5±62.9 | 0.815 |

| P3NP (ng/ml) | 8±5.6 | 11.1±5.6 | 0.068 |

| PIP (ng/ml) | 198.4±86.2 | 202.7±65.3 | 0.837 |

| ICTP (ng/ml) | 5.2±2.3 | 10.2±8.6* | 0.014 |

| PIP/ICTP | 45.5±28.7 | 30.5±20.8* | 0.037 |

| MMP2 (ng/ml) | 35.1±10.9 | 48.6±12* | <0.001 |

| MMP9 (ng/ml) | 55.2±27.2 | 49.3±29 | 0.466 |

| TIMP1 (ng/ml) | 13±4 | 17.3±5.4* | 0.003 |

| MMP2/TIMP | 2.8±0.8 | 2.9±0.9 | 0.628 |

| MMP9/TIMP | 4.9±3.2 | 3±1.8* | 0.009 |

| PGF (pg/ml) | 33.3±21.1 | 73.4±102.3 | 0.084 |

| VEGF (pg/ml) | 512±518 | 437±424 | 0.573 |

| sFlt1 (pg/ml) | 303.5±260.6 | 410.1±254.2 | 0.154 |

| PGF/sFlt1 | 0.16±0.15 | 0.22±0.31 | 0.36 |

| VEGF/sFlt1 | 2.24±2.19 | 1.21±0.82* | 0.023 |

P<0.05:

NYHA class I/II versus class III/IV

Discussion

This study measured for the first time multiple circulating markers of fibrosis and angiogenesis from the same group of patients with HF. The results reveal: 1) A reduction in markers of angiogenesis (PGF/sFlt1, VEGF/sFlt1) and fibrotic deposition (PIP/ICTP) among patients with HF compared to healthy controls; 2) That patients with NICM had decreased circulating pro-angiogenic markers (PGF and PGF/sFlt1 ratio) compared to those with ICM; and 3) That patients with more symptomatic NYHA class III/IV HF had lower PIP/ICTP and VEGF/sFlt ratios. Overall, we observed a circulating multimarker profile consistent with fibrotic degradation and limited angiogenesis in patients with HF.

Our findings have implications for the selection and timing of HF therapy. Guideline directed medical therapy, in particular antagonists of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, has been shown to beneficially alter the course of left heart failure and in selected cases to reduce fibrotic deposition (Hellawell and Margulies, 2012). Therapy is often initiated and up titrated during hospitalization based on tolerability to medication side effects or effects on blood pressure (Yancy et al., 2013). We observed that biomarkers of matrix degradation and decreased angiogenesis are increased in more symptomatic HF patients. Thus administration of therapy that impacts fibrosis often coincides with a time of fibrotic degradation rather than synthesis during the chronic remodeling process. Collagen biomarker data from a sub-study analysis of the RALES clinical trial, which compared spironolactone to placebo in patients with NYHA class III/IV HF and EF<35%, supports the concept that matrix degradation rather than synthesis may be favored in some patients with chronic HF (Zannad et al., 2000). In the placebo arm of the biomarker sub-study, stable PIP and P3NP levels were noted with a trend toward increased ICTP levels resulting in reduced PIP/ICTP and P3NP/ICTP ratios. With spironolactone treatment, PIP and P3NP levels were reduced and ICTP was unchanged, also resulting in reduced PIP/ICTP and P3NP/ICTP ratios. The available collagen biomarker data from the RALES trial and other key clinical trials of anti-fibrotic therapy (EPHESUS, REMODEL) did not stratify patients on the basis of mild and severe HF and do not allow for a direct comparison to our study (Pitt et al., 2003; Udelson et al., 2010). Analysis of the timing of fibrotic deposition and degradation through the course of heart failure disease progression and treatment may facilitate temporal targeting of anti-fibrotic therapies.

Evidence of a critical role for collagen biomarkers as a predictor of patient responsiveness to anti-fibrotic therapy comes from clinical trials of aldosterone antagonists. Indeed the EPHESUS and RALES trials demonstrated a reduction in PIP and P3NP with aldosterone antagonist treatment (Iraqi et al., 2009; Pitt et al., 2003; Pitt et al., 1999) Importantly, a subset study of the RALES trial demonstrated that a mortality benefit was restricted to patients with high (>median) baseline level of P3NP (Zannad et al., 2000). Similarly, in the REMODEL study, which randomized patients with mild-moderate HF with reduced ejection fraction to placebo or epleronone, an improvement in LV remodeling parameters was only observed among patients with high baseline PIP levels (Udelson et al., 2010). Further study of inter- and intra- patient differences in the activity of matrix metabolism during the evolution of heart failure may allow for individualized therapy.

Advanced HF is often associated with progressive deterioration of end organ function thus the finding of increased fibrotic degradation markers in more symptomatic HF patients may be due to changes in collagen turnover in the heart and/or collagen metabolism from non-cardiac sources. PIP and P3NP are metabolized by the liver and are elevated in cirrhotic liver disease (Grigorescu, 2006; Melkko et al., 1994; Smedsrod et al., 1990). The kidney excretes ICTP and increased ICTP levels have been observed in patients with chronic kidney disease (Risteli et al., 1993; Urena and De Vernejoul, 1999). An absence of a trans-myocardial gradient for PIP and P3NP has been observed in patients with advanced HF, lending support to a non-cardiac origin of collagen biomarkers (Kaye et al., 2013). Correlation of collagen biomarkers to myocardial fibrosis has yielded conflicting results depending in part on the study population and methodology (Ellims et al., 2014; Kupari et al., 2013; Querejeta et al., 2004). Even if a direct correlation between peripheral collagen biomarkers and cardiac fibrosis is not established, circulating markers may provide an estimate of total body fibrotic burden attributable to HF and retain value as a marker of ventricular remodeling, progressive end-organ damage, or poor outcomes as observed in multiple studies (Buralli et al., 2010; Frantz et al., 2008; George et al., 2005; Kitahara et al., 2007; Klappacher et al., 1995).

Distinguishing NICM from ICM carries important prognostic and therapeutic implications but remains challenging using non-invasive criteria (Franciosa et al., 1983). Our findings that PGF levels and the PGF/sFlt1 ratio are elevated in ICM compared to NICM may provide a means of differentiating between these types of cardiomyopathy however larger studies are needed to determine if this can be used clinically. Atherosclerotic burden present in patients with ICM may lead to the upregulation of hypoxia-inducible factors, including sFlt1 and PGF (Kapur et al., 2011). Some, but not all, studies have reported an upregulation of vascular growth factors in chronic ICM in contrast to NICM (Ky et al., 2011; Nakamura et al., 2009; Onoue et al., 2009). A cross sectional study of acute myocardial infarction complicated by severe heart failure reported higher PGF levels in ICM but not NICM (Nakamura et al., 2009). A multi-center cohort study utilizing an entry criterion of a clinical diagnosis of HF did not identify an interaction between PGF or sFlt1 levels and HF etiology. The former study was conducted in the setting of acute myocardial ischemia where upregulation of vascular growth factors would be anticipated while the latter study may have included patients with the clinical syndrome of HF with causes other than LV dysfunction. Differences in the acuity of HF and patient characteristics between these studies may account for the disparate findings. In addition, angiogenesis in HF in an incompletely understood phenomenon, and while we focused on VEGF, PGF and sFlt1 as well described circulating surrogates of angiogenesis, other circulating factors surely contribute to the regulation of angiogenesis in HF.

Our study has several limitations. First, the number of subjects in the studied cohort was small and the role of potential confounding factors such as patient demographics, comorbidities and pharmacological treatment cannot be excluded. Second, as the study design was prospective and observational, the role of these markers in prognosis cannot be established. Third, the source of blood was venous in normal controls and arterial in HF pts. While this might have influenced the results of the control vs. HF analysis, we do not expect differences in sampling site to be sufficient to account for the magnitude of the observed differences. Furthermore, the novel findings regarding HF patients were obtained exclusively with arterial sampling. Lastly, we did not observe higher BNP levels between patients with more symptomatic NYHA class III/IV HF compared to NYHA class I/II HF. BNP levels vary significantly among patients with HF and even symptomatic patients may have BNP levels in the normal range (Tang et al., 2003). The size of our study may have precluded demonstrating a difference in BNP levels between mild and severely symptomatic HF. Due to these limitations, further validation of our results is required in a larger patient cohort.

Conclusions

In summary, this study evaluated a panel of angiogenic and fibrotic biomarkers in a single group of patients with HF and identified significant differences in the multimarker profile of HF that if validated in larger cohorts might be useful in differentiating HF etiology or determining the type, timing or dosing of HF therapy.

Footnotes

There are no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Declaration of Interest

The authors have no declaration of interests.

Reference List

- Abraham D, Hofbauer R, Schafer R, et al. Selective downregulation of VEGF-A(165), VEGF-R(1), and decreased capillary density in patients with dilative but not ischemic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2000;87:644–647. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.8.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buralli S, Dini FL, Ballo P, et al. Circulating matrix metalloproteinase-3 and metalloproteinase-9 and tissue Doppler measures of diastolic dysfunction to risk stratify patients with systolic heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:853–856. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P. Angiogenesis in life, disease and medicine. Nature. 2005;438:932–936. doi: 10.1038/nature04478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowie MR, Mosterd A, Wood DA, et al. The epidemiology of heart failure. Eur Heart J. 1997;18:208–225. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies M, Hobbs F, Davis R, et al. Prevalence of left-ventricular systolic dysfunction and heart failure in the Echocardiographic Heart of England Screening study: a population based study. Lancet. 2001;358:439–444. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05620-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez J, Panizo A, Gil MJ, et al. Serum markers of collagen type I metabolism in spontaneously hypertensive rats: relation to myocardial fibrosis. Circulation. 1996;93:1026–1032. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.5.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez J, Querejeta R, Lopez B, et al. Losartan-dependent regression of myocardial fibrosis is associated with reduction of left ventricular chamber stiffness in hypertensive patients. Circulation. 2002;105:2512–2517. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000017264.66561.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellims AH, Taylor AJ, Mariani JA, et al. Evaluating the utility of circulating biomarkers of collagen synthesis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7:271–278. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franciosa JA, Wilen M, Ziesche S, et al. Survival in men with severe chronic left ventricular failure due to either coronary heart disease or idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 1983;51:831–836. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(83)80141-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frantz S, Stork S, Michels K, et al. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases levels in patients with chronic heart failure: an independent predictor of mortality. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10:388–395. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George J, Patal S, Wexler D, et al. Circulating matrix metalloproteinase-2 but not matrix metalloproteinase-3, matrix metalloproteinase-9, or tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 predicts outcome in patients with congestive heart failure. Am Heart J. 2005;150:484–487. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129:e28–e292. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigorescu M. Noninvasive biochemical markers of liver fibrosis. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2006;15:149–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellawell JL, Margulies KB. Myocardial reverse remodeling. Cardiovasc Ther. 2012;30:172–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5922.2010.00247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iraqi W, Rossignol P, Angioi M, et al. Extracellular cardiac matrix biomarkers in patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by left ventricular dysfunction and heart failure: insights from the Eplerenone Post-Acute Myocardial Infarction Heart Failure Efficacy and Survival Study (EPHESUS) study. Circulation. 2009;119:2471–2479. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.809194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izawa H, Murohara T, Nagata K, et al. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism ameliorates left ventricular diastolic dysfunction and myocardial fibrosis in mildly symptomatic patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy: a pilot study. Circulation. 2005;112:2940–2945. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.571653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumiya Y, Shiojima I, Sato K, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor blockade promotes the transition from compensatory cardiac hypertrophy to failure in response to pressure overload. Hypertension. 2006;47:887–893. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000215207.54689.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe IZ, Newfell BG, Aronovitz M, et al. Placental growth factor mediates aldosterone-dependent vascular injury in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3891–3900. doi: 10.1172/JCI40205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Januzzi JL, Jr, Felker GM. Surfingthe biomarker tsunami at JACC: heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2013;1:213–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur NK, Heffernan KS, Yunis AA, et al. Elevated soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 levels in acute coronary occlusion. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:443–450. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.215897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye DM, Khammy O, Mariani J, et al. Relationship of circulating matrix biomarkers to myocardial matrix metabolism in advanced heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15:292–298. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitahara T, Takeishi Y, Arimoto T, et al. Serum carboxy-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen (ICTP) predicts cardiac events in chronic heart failure patients with preserved left ventricular systolic function. Circ J. 2007;71:929–935. doi: 10.1253/circj.71.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klappacher G, Franzen P, Haab D, et al. Measuring extracellular matrix turnover in the serum of patients with idiopathic or ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy and impact on diagnosis and prognosis. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:913–918. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80686-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama Y, Kitta Y, Nakamura T, et al. Atorvastatin increases plasma soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 and decreases vascular endothelial growth factor and placental growth factor in association with improvement of ventricular function in acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koitabashi N, Danner T, Zaiman AL, et al. Pivotal role of cardiomyocyte TGF-beta signaling in the murine pathological response to sustained pressure overload. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2301–2312. doi: 10.1172/JCI44824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupari M, Laine M, Turto H, et al. Circulating collagen metabolites, myocardial fibrosis and heart failure in aortic valve stenosis. J Heart Valve Dis. 2013;22:166–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ky B, French B, Ruparel K, et al. The vascular marker soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 is associated with disease severity and adverse outcomes in chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:386–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leask A. Potential therapeutic targets for cardiac fibrosis: TGFbeta, angiotensin, endothelin, CCN2, and PDGF, partners in fibroblast activation. Circ Res. 2010;106:1675–1680. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.217737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine RJ, Lam C, Qian C, et al. Soluble endoglin and other circulating antiangiogenic factors in preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:992–1005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lip GY, Chung I. Vascular endothelial growth factor and angiogenesis in heart failure. J Card Fail. 2005;11:285–287. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez B, Gonzalez A, Diez J. Circulating biomarkers of collagen metabolism in cardiac diseases. Circulation. 2010;121:1645–1654. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.912774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttun A, Tjwa M, Moons L, et al. Revascularization of ischemic tissues by PlGF treatment, and inhibition of tumor angiogenesis, arthritis and atherosclerosis by anti-Flt1. Nat Med. 2002;8:831–840. doi: 10.1038/nm731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melkko J, Hellevik T, Risteli L, et al. Clearance of NH2-terminal propeptides of types I and III procollagen is a physiological function of the scavenger receptor in liver endothelial cells. J Exp Med. 1994;179:405–412. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagamatsu T, Fujii T, Kusumi M, et al. Cytotrophoblasts up-regulate soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 expression under reduced oxygen: an implication for the placental vascular development and the pathophysiology of preeclampsia. Endocrinology. 2004;145:4838–4845. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Funayama H, Kubo N, et al. Elevation of plasma placental growth factor in the patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 2009;131:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onoue K, Uemura S, Takeda Y, et al. Usefulness of soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 as a biomarker of acute severe heart failure in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:1478–1483. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parenti A, Brogelli L, Filippi S, et al. Effect of hypoxia and endothelial loss on vascular smooth muscle cell responsiveness to VEGF-A: role of flt-1/VEGF-receptor-1. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;55:201–212. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00326-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilarczyk K, Sattler KJ, Galili O, et al. Placenta growth factor expression in human atherosclerotic carotid plaques is related to plaque destabilization. Atherosclerosis. 2008;196:333–340. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt B, Remme W, Zannad F, et al. Eplerenone, a selective aldosterone blocker, in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1309–1321. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ, et al. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:709–717. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909023411001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruthi D, McCurley A, Aronovitz M, et al. Aldosterone promotes vascular remodeling by direct effects on smooth muscle cell mineralocorticoid receptors. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:355–364. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.302854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Querejeta R, Lopez B, Gonzalez A, et al. Increased collagen type I synthesis in patients with heart failure of hypertensive origin: relation to myocardial fibrosis. Circulation. 2004;110:1263–1268. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140973.60992.9A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi N, Golde TE, Meyer RD. Identification of ligand-induced proteolytic cleavage and ectodomain shedding of VEGFR-1/FLT1 in leukemic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2607–2614. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risteli J, Elomaa I, Niemi S, et al. Radioimmunoassay for the pyridinoline cross-linked carboxy-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen: a new serum marker of bone collagen degradation. Clin Chem. 1993;39:635–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedsrod B, Melkko J, Risteli L, et al. Circulating C-terminal propeptide of type I procollagen is cleared mainly via the mannose receptor in liver endothelial cells. Biochem J. 1990;271:345–350. doi: 10.1042/bj2710345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang WH, Girod JP, Lee MJ, et al. Plasma B-type natriuretic peptide levels in ambulatory patients with established chronic symptomatic systolic heart failure. Circulation. 2003;108:2964–2966. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000106903.98196.B6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udelson JE, Feldman AM, Greenberg B, et al. Randomized, double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled study evaluating the effect of aldosterone antagonism with eplerenone on ventricular remodeling in patients with mild-to-moderate heart failure and left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Circ Heart Fail. 2010;3:347–353. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.906909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urena P, De Vernejoul MC. Circulating biochemical markers of bone remodeling in uremic patients. Kidney Int. 1999;55:2141–2156. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valgimigli M, Rigolin GM, Fucili A, et al. CD34+ and endothelial progenitor cells in patients with various degrees of congestive heart failure. Circulation. 2004;110:1209–1212. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000136813.89036.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:1810–1852. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano K, Liaw PC, Mullington JM, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor is an important determinant of sepsis morbidity and mortality. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1447–1458. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zannad F. What is measured by cardiac fibrosis biomarkers and imaging? Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7:239–242. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zannad F, Alla F, Dousset B, et al. Limitation of excessive extracellular matrix turnover may contribute to survival benefit of spironolactone therapy in patients with congestive heart failure: insights from the randomized aldactone evaluation study (RALES). Rales Investigators. Circulation. 2000;102:2700–2706. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.22.2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zannad F, McMurray JJ, Krum H, et al. Eplerenone in patients with systolic heart failure and mild symptoms. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:11–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]