Abstract

Delayed orgasm/anorgasmia defined as the persistent or recurrent difficulty, delay in, or absence of attaining orgasm after sufficient sexual stimulation, which causes personal distress. Delayed orgasm and anorgasmia are associated with significant sexual dissatisfaction. A focused medical history can shed light on the potential etiologies; which include: medications, penile sensation loss, endocrinopathies, penile hyperstimulation and psychological etiologies, amongst others. Unfortunately, there are no excellent pharmacotherapies for delayed orgasm/anorgasmia, and treatment revolves largely around addressing potential causative factors and psychotherapy.

Keywords: delayed orgasm, anorgasmia, delayed ejaculation, retarded orgasm, inhibited orgasm

1. Introduction

Delayed orgasm (DO) and anorgasmia (AO) have been described as one end of a spectrum of orgasm timing disorders with the other end being premature ejaculation (1). DO/AO defined as the persistent or recurrent difficulty, delay in, or absence of attaining orgasm after sufficient sexual stimulation, which causes personal distress. DO has also been termed retarded orgasm, inhibited orgasm, retarded ejaculation and or inhibited ejaculation. We believe that DO is the correct term as some men fail to ejaculate for medical reasons but still experience orgasm (retroperitoneal surgery, radical prostatectomy). One of the major concerns with DO and in particular anorgasmia, young males or men with reproductive interest, is the failure to inseminate and therefore male infertility. Men with DO may develop anxiety and frustration, which may lead to other sexual problems such as erectile dysfunction (ED) and loss of sex drive. It is critically important to understand that orgasm is an entirely separate process from ejaculation, although they are designed to occur simultaneously.

In the clinical setting, most men with failure to ejaculate (retrograde ejaculation, failure of emission both addressed elsewhere in this issue) experience orgasm (although a man with failure to ejaculate for medical reasons may also have DO or anorgasmia). However, men with anorgasmia will not ejaculate.

2. Definition

The best definition is probably that of the World Health Organization 2nd Consultation on Sexual Dysfunction defines DO as the persistent or recurrent difficulty, delay in, or absence of attaining orgasm after sufficient sexual stimulation, which causes personal distress (2). The International Consultation on Sexual Medicine defines anorgasmia as the perceived absence of orgasm, independent of the presence of ejaculation. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth edition (DSM-5) defines delayed orgasm as a marked delay in ejaculation or a marked infrequency or absence of ejaculation on almost all or all occasions (75–100%) of partnered sexual activity without the individual desiring delay, persisting for at least 6 months and causing significant distress to the individual (3). The sexual dysfunction is not explained by another non-sexual disorder, medication or significant relation/life distress/stressors.

DO is further classified as lifelong/acquired, generalized/situational, and mild/moderate/severe. An acquired dysfunction establishes that the patient previously had normal orgasm timing. Situational dysfunction implies the man has problems in a particular scenario or scenarios while functioning normally in others.

There is no set time threshold for what defines DO. Time threshold for distress is dependent on the partners involved. Some males will reach orgasm with one partner in 15 minutes and have no distress, but with another partner it may cause severe distress because the partner may complain of pain with prolonged intercourse. A population-based survey established that the median intravaginal ejaculatory latency time (IELT) was 5.4 minutes and 2 standard deviations above was approximately 22 minutes (4–6). A provider with a patient complaining of IELT longer than 22 minutes will theoretically qualify him for the diagnosis of DO. One should differentiate between problems with of ejaculation and orgasm.

3. Physiology of orgasm

Orgasm is a complex neurobiological process that comes as a result of sexual activity (physical sensation) and/or arousal (cognitive awareness). The physiology of ejaculation is discussed elsewhere. When ejaculation occurs, the brain processes the sensation of the pressure buildup within the posterior urethra (bladder neck and external urinary sphincter are closed contemporaneously) leading up to seminal fluid emission and the contraction of the peri-urethral musculature. This processing leads to the triggering of an orgasm.

Advances in functional neuroimaging have been able to show the location of increased brain activity during orgasm (7). PET imaging has demonstrated that sexual stimulation leads to increased activity in the occipitotemporal, anterior cingulate and insular cortices, as well as bilateral activation in the substantia nigra (8). During orgasm there is a decrease in regional cerebral blood flow across the prefrontal cortex (right medial orbitofrontal, left lateral orbitofrontal, left dorsolateral) and in the left temporal lobe (fusiform gyrus, superior temporal gyrus), as well as increased activation in the left dentate cerebellar nucleus, left lateral midbrain, and right pons (8, 9).

4. Prevalence

DSM-5 states that only 25% of males routinely achieve orgasm in all sexual encounters. According to the DSM-5, the prevalence remains constant up until age 50 and then the rate steadily increases with men in their 80s complaining twice as much as men under age 59 (3). The increase with age is likely multifactorial and may be related to a combination of: changes in penile sensitivity, increased prevalence of testosterone deficiency, increased use of offending medications, decreased exercise tolerance and reduced partner tolerance for prolonged sexual intercourse. In one study, the prevalence of primary DO was found to be 1.5 in 1000 and secondary DO in men under age 65 was 3–4% (10, 11). Masters and Johnson only reported on 17 cases (12), Apfelbaum reported 34 cases(13), and Kaplan reported <50 cases (14). Because this is such an uncommon complaint, the true prevalence is probably underestimated. In a study by Carani et al, they assessed 48 adult men, 14 with hypothyroidism and 34 with hyperthyroidism, and DO was identified in 64% of the hypothyroid patients and 3% of the hyperthyroid patients (15).

5. Pathophysiology

By definition, primary anorgasmia begins from the male’s first sexual experiences and lasts throughout his life. Whereas, secondary anorgasmia is preceded by a period of normal sexual experiences before the problem manifests. A Finnish population-based, twin study found there was no evidence of a genetic influence on DO/AO but there was a moderate familial effect with shared environments, which accounted for 24% of the variance (16). This study included 1,196 twins and their siblings using retrospective self-reported data. Table 1 provides a summary of the different possible causes for DO.

Table 1.

Causes of delayed orgasm and anorgasmia

| Endocrine | Testosterone deficiency Hypothyroidism Hyperprolactinemia |

| Medication | Antidepressants Antipsychotics Opiods |

| Psychosexual Causes | |

| Hyperstimulation | |

| Penile sensation loss |

In a study by Teloken et al, they performed an analysis of data on 206 patients who presented with secondary DO/AO (17). The etiology for their condition were divided into selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) use (42%), low testosterone (21%; mean total testosterone 268±111 ng/dL), abnormal penile sensation (7%), chronic/idiosyncratic penile (hyper)stimulation (2%) and psychogenic (28%). Age-related hormonal declines (lower testosterone levels) and age-related loss of peripheral nerve conduction may account for the increased onset over age 50 years (3). It has also been suggested that hormonal aberrations such as hypothyroidism and testosterone deficiency may also play a role in DO (1).

5.1 Endocrinopathies

The role of prolactin in men is not fully understood. However, it is well understood that prolactin levels above normal, hyperprolactinemia, may result in an inhibitory effect on sexual desire (18–20). Mild forms of hyperprolactinemia (defined as >420 mU/L or 20 ng/mL) generally do not have an impact on sexual function; however, severe hyperprolactinemia (defined as >735 mU/L or 35 ng/mL) can have significant effects on sexual function, including erectile dysfunction and testosterone production suppression (18, 19, 21, 22). Prolactin secretion is positively influenced by prolactin-releasing factors (PRFs): thyroid-releasing hormone, oxytocin, vasopressin, and vasoactive intestinal peptide (23). Serotonin is implicated in the control of prolactin secretion via serotoninergic inputs from the dorsal raphe nucleus stimulating PRFs in the paraventricular nucleus (24). SSRIs are therefore capable of causing hyperprolactinemia and lead to DO/AO (25). Corona et al identified relationships between ejaculation and prolactin, thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), and testosterone levels (1). Knowing that DO and premature ejaculation (PE) represent two ends of a linear spectrum, it has been shown that prolactin and TSH levels progressively increased from patients with PE to those with DO, and the opposite was true for testosterone.

5.2 Hyperstimulation

Some men obtain greater pleasure from masturbation than they do with sexual intercourse and may continue deep-rooted habits such as frequent masturbation or using idiosyncratic masturbation techniques. Studies have shown a correlation between DO and men with idiosyncratic masturbation practices (5, 14). Also, with increasing frequency of masturbation the sensitivity of the penis can decline and lead to a vicious cycle where the man increases masturbation force to counteract the declining sensitivity, therefore leading to worsening DO. Vaginal intercourse or orogenital stimulation may not be able to replicate the stimulation achieved through idiosyncratic masturbation and this may result in reduced penile stimulation leading to difficulty achieving an orgasm (5, 14, 26).

Patients with DO have been shown to have higher masturbatory activity, decreased night-time emissions, lower orgasm and intercourse satisfaction scores on the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF), as well as higher anxiety and depression scores when compared to controls (27). In a study by Xia et al, they compared 24 patients with primary DO and 24 age-matched controls who had no sexual dysfunction complaints (28). They showed that patients with primary DO had significantly longer IELT (20 vs 5.5 minutes), higher frequency of masturbation, lower nocturnal emissions, and higher rates of anxiety and depression. They also found that although DO patients had normal glans sensation, they reported penile shaft hyposensitivity and hypoexcitability. The patients with DO were also found to more commonly use idiosyncratic masturbation methods.

5.3 Penile Sensation Loss

Penile sensation loss has been shown to increase with age (29). In a literature review (13 studies) by Rowland et al, they plotted penile sensory thresholds as a function of age as well as sexual functional status (30). They found penile sensation loss was more commonly present in those men with increased age and those with sexual dysfunctions.

5.4 Psychosexual Causes

Lifelong DO has been associated with multiple psychological conditions. Some of these conditions include fear, anxiety, hostility, and relationship difficulties (31, 32). Fear and anxiety during sexual relations have been examined, and the most common triggers included: hurting the female, impregnating the female, childhood sexual abuse, sexual trauma, repressive sexual education/religion, sexual anxiety, general anxiety, “spilling of seed,” and conflict in men in their first sexual relationship after becoming widowed or divorced (11).

The man may also suffer from a lack in sexual arousal, thus inhibiting his ability to reach orgasm. The man may achieve an erection without reaching adequate arousal to proceed with intercourse, such as men who achieve an erection with the assistance of erectogenic medications. With the assistance of medication, men are more likely to get an erection without significant psychoemotional arousal or the necessary mental/physical stimulation needed to reach orgasm (33–35).

DO based on a situational aspect (i.e. difficulties with a specific partner and not another) is more likely to be due to a psychologic etiology (36). One study looked at stress and anxiety related to timed intercourse demands for fertility treatments and found DO developed in 6% of patients related to elevated anxiety levels (37). A novel study by Kirby et al used a rat model to show how stress can suppress the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis which is important in healthy normal sexual function (38). They showed that acute and chronic immobilization stress led to an increase in adrenal glucocorticoids causing an increase in gonadotropin inhibitory hormone which suppresses the HPG axis via inhibition of gonadotropin releasing hormone.

5.5 SSRIs/Medications

There are numerous medications that have been implicated in the genesis of DO including antidepressants (especially SSRIs), antipsychotics, and opioids (3). In a study by Corona et al, approximately 2000 male patients were evaluated for the sexual effects of anti-depressant therapy (39). A seven-fold risk for DO was observed in SSRI patients, and they had a two-fold risk of low libido. In a study by Clayton et al, the effects on sexual functioning and antidepressant efficacy of bupropion extended release was compared with escitalopram (40). The incidence of orgasm dysfunction and worsened sexual function at week 8 was statistically significantly higher in the escitalopram (30%) vs bupropion (15%) and escitalopram (30%) vs placebo (9%) groups but not statistically significant in the bupropion (15%) vs placebo (9%) groups.

6. Patient Evaluation

6.1 History and Physical Exam

Management should begin with a good medical/psychosexual history, social/religious history, medication list, and physical exam. Focusing on the major etiologic factors (as listed above) is a useful starting point. Medication history should focus on SSRI agents and other psychotropic agents, and define the onset of the use of the medication as it pertains to the timing of onset of DO. Asking about penile sensitivity is a useful question, especially in men at risk for penile sensation loss such as diabetics. Symptoms and signs of endocrinopathies such as testosterone deficiency, hypothyroidism and hyperprolactinemia should be sought. Masturbatory style is another useful line of inquiry as frequent masturbation or idiosyncratic masturbatory styles may lead to DO. Defining relationship status, satisfaction and the role external stressors may be playing in the DO genesis is also important.

Furthermore, identifying the onset of the DO is critical, whether lifelong or acquired. Next, understanding whether the condition is generalized or situational is also critical to understanding the pathophysiology. Asking patients to describe a typical sexual encounter is often a useful ploy to unearth potential contributing factors. Defining the consistency of the problem, that is: “does it happen all the time or only some of the time? with sexual intercourse and sexual outercourse with a partner? and how this differs between partner-based relations and masturbation?” For example, men who achieve orgasm with masturbation but have difficulty with partner-based relations often have one of two factors as causes – loss of penile sensitivity (overcome by vigorous masturbation) or psychological issues (interpersonal conflict, fear, anxiety, or hostility). Inquiring about how long a man attempts relations before stopping may also provide valuable insight into the problem. Some older men, due to inadequate exercise reserve of upper body strength, cease sexual relations sooner than they did when they were younger and thus interpret this as DO. Finally, asking about strategies or medications that have been tried previously for this problem will aid in plotting a course of treatment.

6.2 Adjunctive Testing

The role of laboratory testing, such a testosterone and TSH levels, is optional and is applied depending upon patient symptoms. If laboratory values are abnormal, endocrine function should be corrected. As shown by Carani et al, with correction of thyroid hormone levels, patients had significant improvements in DO (15). After thyroid hormone treatment and normalization of lab values, half of the hypothyroid patients reported their DO improved, and IELT improved from 22 to 7 minutes.

In patients complaining of loss of penile sensitivity, biothesiometry (Figure 1) and/or pudendal somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEP) might be warranted (5). Biothesiometry examines the sensory threshold of vibratory tactile stimulation. Pudendal SSEP evaluates the afferent activity from the dorsal nerve of the penis towards the brain. Sympathetic skin testing is another test that allows the evaluation of sympathetic efferent flow to the skin of the genitals. Lastly, sacral reflex arc testing examines the motor and sensory branches of the pudendal nerve and nerve roots S2, S3, and S4 (41).

Figure 1.

Bio-Thesiometer. Bio-Medical Instrument Company, Newbury, Ohio

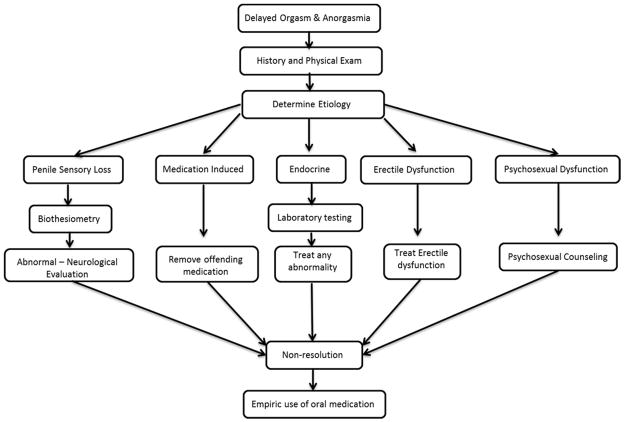

7. Management Strategies (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Management Algorithm [adapted from (57)]

Various lifestyle changes include: steps to improve intimacy, reduce masturbation frequency, change of masturbation style and decreasing alcohol consumption, (5, 11).

7.1 Psychosexual Counseling

Once the organic causes are ruled out and in some cases contemporaneously, the patient may benefit from a thorough psychosexual evaluation (along with his partner). There are numerous types of psychotherapy techniques that have been used with DO including: masturbation retraining/desensitization, adjustments of sexual fantasies, changes in arousal methods, sexual education, sexual anxiety reduction, increased genital stimulation, and role playing an exaggerated orgasm alone and/or with his partner (5, 42). There are numerous strategies that utilize combinations of approaches, but that is beyond the scope of this article. Success rates are difficult to determine from literature, and few have had significant testing of their results.

7.2 Pharmacotherapy (Table 2)

Table 2.

Pharmacotherapeutic Management of Delayed Orgasm

| Drug | As needed dosing | Continuous dosing |

|---|---|---|

| Bupropion | 15 – 60 mg | 150 mg (sustained release) |

| Cyproheptadine | 4 – 12 mg | |

| Amantadine | 100 – 400 mg | 75 – 100 mg bid or tid |

| Yohimbine | 20 – 40 mg | |

| Oxytocin | 20 – 24 IU | |

| Anandamide | n/a | n/a |

| Cabergoline | 0.5 mg | |

| Testosterone Supplementation | based on testosterone | |

There are no FDA approved drugs for DO, and those drugs that have been studied often have limited efficacy or significant side effect profiles. One could first consider withdrawing any offending medications if possible, such as SSRIs, although it is our clinical practice to liaise with the SSRI-prescribing clinician and have them coordinate the drug manipulation (drug holiday, substitution or cessation) and monitor the patient.

Some medications are used to counteract the side effects of other medications. Bupropion (open-label bupropion-SR 150 mg/day for 2 months) was trialed in an age-matched group of 19 males with reported lifelong DO (27). There was a 25% decrease in mean IELT, and the percentage rating control over ejaculation as “fair to good” increased from 0 to 21%. Also, orgasm and intercourse satisfaction domain scores on the IIEF improved significantly from baseline after treatment.

Cyproheptadine, an anti-histamine known to increase brain serotonin levels, has been studied to treat DO related to SSRI use (5, 43, 44). However, there have been no large randomized controlled studies conducted with this agent to date. In a small study by Ashton et al, improvement was seen in 12/25 men treated with cyproheptadine for SSRI-induced DO (43). Treatment was limited by sedation and reversal of the antidepressant’s effects.

Amantadine, an indirect stimulant of central and peripheral dopaminergic nerves, has been used by some investigators to stimulate sexual behavior in rats (41). In a human study, Ashton et al used amantadine to treat SSRI-induced DO and found improvements in 8/19 men (43).

Ashton also used yohimbine and found improvements treating men with SSRI-induced DO. Yohimbine is a product from the bark of the Pausinystalia johimbe tree and functions as an α-2 adrenergic receptor blocker. Yohimbine has been used as a traditional medicine in Africa as an aphrodisiac, and is being studied as a possible medication to treat ED. Several groups have studied yohimbine to treat other sexual dysfunctions (45–47). Adeniyi et al performed a study using yohimbine in 29 patients with anorgasmia who presented to their clinic with complaints of infertility or orgasmic dysfunction (45). The patients achieved orgasm at a mean yohimbine dose of 38 mg. In all, 19 men achieved orgasm; however, 3 required the use of penile vibratory stimulation (PVS). Also, 7 out of 8 men with secondary AO were able to achieve orgasm.

Oxytocin is a nine amino acid peptide released by the posterior pituitary at higher levels during orgasm. Ishak et al reported on one case of oxytocin used successfully for the treatment of anorgasmia (48). The patient was given a 20–24 IU dose of oxytocin intranasally when he was ready to orgasm, and a positive response was reported through at least 8 months of follow up.

A rat model (sexually sluggish male rats) has been used to study low dose endocannabinoid anandamide effects on the CB1 cannabinoid receptor to lower the ejaculatory threshold (49). Their results were encouraging and found that low dose anandamide did lower the ejaculatory threshold in their study group. The effects were temporary and the rats no longer displayed the behavior 7 days after the initial dosing. There were no effects observed on other sexual behaviors.

7.3 Endocrine Therapy

The dopamine agonist cabergoline has been shown to augment plasma prolactin levels and was studied for its utility in treating psychogenic erectile dysfunction (ED) (50, 51). In one study, patients were treated with cabergoline 0.5 mg for 4 months in a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial with 25 patients in the active arm and 25 in the placebo arm. Baseline hyperprolactinemia was found in 38 of the patients, in addition, after the treatment period ended both prolactin and testosterone levels normalized in most of the patients. Erectile function, orgasmic function, and sexual desire were all enhanced based on IIEF questionnaire scores.

Testosterone plays an important role in sexual response and motivation with effects at both the central and peripheral levels. Testosterone also plays a facilitative role in the orgasmic response mechanism (52). Hackett et al performed a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial on 190 men with testosterone deficiency and type 2 diabetes using long acting testosterone injections over 30 weeks (53). They found patients had improvements in most sexual function areas, including orgasm (based on the orgasm domain of the IIEF questionnaire 5.7±4. vs 4±4, p=0.004).

Corona et al performed a meta-analysis examining studies about testosterone supplementation and sexual function (54). Data was available on the effect of testosterone supplementation on orgasmic function in 10 studies totaling 677 patients. They identified an inverse relationship between testosterone levels and the influence treatment caused on the orgasm domain of the IIEF. The mean difference in the IIEF orgasm function domain between the treatment groups and placebo was 1.62 (95% Confidence Interval 0.000; 3.229, p=0.05).

7.4 Penile Vibratory Stimulation

DO can successfully be treated in some cases using penile vibratory stimulation (PVS) in patients with penile sensitivity loss. In PVS, a vibrator is applied to the frenular area of the glans penis to produce mechanical stimulation to trigger orgasm. A study by Nelson et al examined the use of PVS to restore orgasmic and erectile function (55). They found that with PVS use, 72% of patients reported restoration of orgasm on at least some occasions, and they self-reported that 62% of their attempts at sexual relations resulted in orgasm. The responders had significant increases in IIEF orgasm and satisfaction domain scores at 3 months.

7.5 Electroejaculation (EEJ)

In select patients with recalcitrant DO who have failed all other conservative methods, EEJ is a viable option to retrieve semen for fertility purposes. Electroejaculation requires placement of a transrectal probe and the delivery of low-level electric current in patients without spinal cord injury. EEJ is performed under general anesthesia and routinely leads to the procurement of an ejaculate (56).

8.0 Summary

Delayed orgasm and anorgasmia are associated with significant sexual dissatisfaction. A focused medical history can shed light on the potential etiologies. SSRI medications, penile sensation loss, endocrinopathies, penile hyperstimulation and psychological issues represent the major etiologies. Unfortunately, there are no excellent pharmacotherapies for DO/AO, and treatment revolves largely around addressing potential causative factors as well as the use of psychotherapy.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

References

- 1.Corona G, Jannini EA, Lotti F, Boddi V, De Vita G, Forti G, et al. Premature and delayed ejaculation: two ends of a single continuum influenced by hormonal milieu. International journal of andrology. 2011;34:41–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2010.01059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McMahon CG, Althof SE, Waldinger MD, Porst H, Dean J, Sharlip ID, et al. An evidence-based definition of lifelong premature ejaculation: report of the International Society for Sexual Medicine (ISSM) ad hoc committee for the definition of premature ejaculation. The journal of sexual medicine. 2008;5:1590–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric A, American Psychiatric A, Force DSMT. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waldinger MD, Quinn P, Dilleen M, Mundayat R, Schweitzer DH, Boolell M. A multinational population survey of intravaginal ejaculation latency time. The journal of sexual medicine. 2005;2:492–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McMahon CG, Jannini E, Waldinger M, Rowland D. Standard operating procedures in the disorders of orgasm and ejaculation. The journal of sexual medicine. 2013;10:204–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patrick DL, Althof SE, Pryor JL, Rosen R, Rowland DL, Ho KF, et al. Premature ejaculation: an observational study of men and their partners. The journal of sexual medicine. 2005;2:358–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.20353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stoleru S, Fonteille V, Cornelis C, Joyal C, Moulier V. Functional neuroimaging studies of sexual arousal and orgasm in healthy men and women: a review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36:1481–509. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Georgiadis JR, Reinders AA, Van der Graaf FH, Paans AM, Kortekaas R. Brain activation during human male ejaculation revisited. Neuroreport. 2007;18:553–7. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3280b10bfe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Georgiadis JR, Reinders AA, Paans AM, Renken R, Kortekaas R. Men versus women on sexual brain function: prominent differences during tactile genital stimulation, but not during orgasm. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;30:3089–101. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nathan SG. The epidemiology of the DSM-III psychosexual dysfunctions. J Sex Marital Ther. 1986;12:267–81. doi: 10.1080/00926238608415413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waldinger MD, Schweitzer DH. Retarded ejaculation in men: an overview of psychological and neurobiological insights. World journal of urology. 2005;23:76–81. doi: 10.1007/s00345-004-0487-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human sexual inadequacy. London: Churchill; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leiblum SR, Rosen R. Principles and practice of sex therapy. 3. New York: Guilford Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perelman MA, Rowland DL. Retarded ejaculation. World journal of urology. 2006;24:645–52. doi: 10.1007/s00345-006-0127-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carani C, Isidori AM, Granata A, Carosa E, Maggi M, Lenzi A, et al. Multicenter study on the prevalence of sexual symptoms in male hypo- and hyperthyroid patients. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2005;90:6472–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jern P, Santtila P, Witting K, Alanko K, Harlaar N, Johansson A, et al. Premature and delayed ejaculation: genetic and environmental effects in a population-based sample of Finnish twins. The journal of sexual medicine. 2007;4:1739–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teloken P, Nelson C, Mulhall J. 1384 SECONDARY DELAYED ORGASM: PATTERNS, CORRELATES AND PREDICTORS. The Journal of urology. 2012;187:e562. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buvat J. Hyperprolactinemia and sexual function in men: a short review. Int J Impot Res. 2003;15:373–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corona G. Effect of hyperprolactinemia in male patients consulting for sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2007;4:1485–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corona G. The impotent couple: low desire. Int J Androl. 2005;28:46–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2005.00594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corona G. Psycho-biological correlates of hypoactive sexual desire in patients with erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 2004;16:275–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balercia G. Sexual symptoms in endocrine diseases: psychosomatic perspectives. Psychother Psychosom. 2007;76:134–40. doi: 10.1159/000099840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corona G, Jannini EA, Vignozzi L, Rastrelli G, Maggi M. The hormonal control of ejaculation. Nature reviews Urology. 2012;9:508–19. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2012.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van de Kar LD, Bethea CL. Pharmacological evidence that serotonergic stimulation of prolactin secretion is mediated via the dorsal raphe nucleus. Neuroendocrinology. 1982;35:225–30. doi: 10.1159/000123386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giuliano F. Neurophysiology of erection and ejaculation. J Sex Med. 2011;8:310–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rowland D, McMahon CG, Abdo C, Chen J, Jannini E, Waldinger MD, et al. Disorders of orgasm and ejaculation in men. The journal of sexual medicine. 2010;7:1668–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abdel-Hamid IA, Saleh el S. Primary lifelong delayed ejaculation: characteristics and response to bupropion. The journal of sexual medicine. 2011;8:1772–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xia JD, Han YF, Pan F, Zhou LH, Chen Y, Dai YT. Clinical characteristics and penile afferent neuronal function in patients with primary delayed ejaculation. Andrology. 2013;1:787–92. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-2927.2013.00119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson RD, Murray FT. Reduced sensitivity of penile mechanoreceptors in aging rats with sexual dysfunction. Brain Res Bull. 1992;28:61–4. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(92)90231-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rowland DL. Penile sensitivity in men: a composite of recent findings. Urology. 1998;52:1101–5. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00413-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Munjack DJ, Kanno PH. Retarded ejaculation: a review. Archives of sexual behavior. 1979;8:139–50. doi: 10.1007/BF01541234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shull GR, Sprenkle DH. Retarded ejaculation reconceptualization and implications for treatment. J Sex Marital Ther. 1980;6:234–46. doi: 10.1080/00926238008406089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perelman MA. Regarding ejaculation, delayed and otherwise. Journal of andrology. 2003;24:496. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.2003.tb02699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nurnberg HG, Hensley PL, Gelenberg AJ, Fava M, Lauriello J, Paine S. Treatment of antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction with sildenafil: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289:56–64. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perelman M. Sildenafil, Sex Therapy, and Retarded Ejaculation. J Sex Educ Ther. 2001;26:13–21. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rowland DL. Psychophysiology of ejaculatory function and dysfunction. World journal of urology. 2005;23:82–8. doi: 10.1007/s00345-004-0488-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Byun JS, Lyu SW, Seok HH, Kim WJ, Shim SH, Bak CW. Sexual dysfunctions induced by stress of timed intercourse and medical treatment. BJU international. 2013;111:E227–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kirby ED, Geraghty AC, Ubuka T, Bentley GE, Kaufer D. Stress increases putative gonadotropin inhibitory hormone and decreases luteinizing hormone in male rats. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:11324–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901176106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Corona G, Ricca V, Bandini E, Mannucci E, Lotti F, Boddi V, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-induced sexual dysfunction. The journal of sexual medicine. 2009;6:1259–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clayton AH, Croft HA, Horrigan JP, Wightman DS, Krishen A, Richard NE, et al. Bupropion extended release compared with escitalopram: effects on sexual functioning and antidepressant efficacy in 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:736–46. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.SEXUAL MEDICINE Sexual Dysfunctions in Men and Women. 2010 ed: International Consultation on Urological Diseases. International Society for Sexual Medicine; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Althof SE. Psychological interventions for delayed ejaculation/orgasm. International journal of impotence research. 2012;24:131–6. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2012.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ashton AK, Hamer R, Rosen RC. Serotonin reuptake inhibitor-induced sexual dysfunction and its treatment: a large-scale retrospective study of 596 psychiatric outpatients. J Sex Marital Ther. 1997;23:165–75. doi: 10.1080/00926239708403922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCormick S, Olin J, Brotman AW. Reversal of fluoxetine-induced anorgasmia by cyproheptadine in two patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990;51:383–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adeniyi AA, Brindley GS, Pryor JP, Ralph DJ. Yohimbine in the treatment of orgasmic dysfunction. Asian journal of andrology. 2007;9:403–7. doi: 10.1111/J.1745-7262.2007.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hollander E, McCarley A. Yohimbine treatment of sexual side effects induced by serotonin reuptake blockers. J Clin Psychiatry. 1992;53:207–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guay AT, Spark RF, Jacobson J, Murray FT, Geisser ME. Yohimbine treatment of organic erectile dysfunction in a dose-escalation trial. International journal of impotence research. 2002;14:25–31. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ishak WW, Berman DS, Peters A. Male anorgasmia treated with oxytocin. The journal of sexual medicine. 2008;5:1022–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rodriguez-Manzo G, Canseco-Alba A. Anandamide reduces the ejaculatory threshold of sexually sluggish male rats: possible relevance for human lifelong delayed ejaculation disorder. The journal of sexual medicine. 2015;12:1128–35. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nickel M, Moleda D, Loew T, Rother W, Pedrosa Gil F. Cabergoline treatment in men with psychogenic erectile dysfunction: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. International journal of impotence research. 2007;19:104–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kruger TH, Haake P, Haverkamp J, Kramer M, Exton MS, Saller B, et al. Effects of acute prolactin manipulation on sexual drive and function in males. J Endocrinol. 2003;179:357–65. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1790357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Corona G. Different testosterone levels are associated with ejaculatory dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2008;5:1991–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hackett G, Cole N, Bhartia M, Kennedy D, Raju J, Wilkinson P. Testosterone replacement therapy with long-acting testosterone undecanoate improves sexual function and quality-of-life parameters vs. placebo in a population of men with type 2 diabetes. The journal of sexual medicine. 2013;10:1612–27. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Corona G, Isidori AM, Buvat J, Aversa A, Rastrelli G, Hackett G, et al. Testosterone supplementation and sexual function: a meta-analysis study. The journal of sexual medicine. 2014;11:1577–92. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nelson CJ, Ahmed A, Valenzuela R, Parker M, Mulhall JP. Assessment of penile vibratory stimulation as a management strategy in men with secondary retarded orgasm. Urology. 2007;69:552–5. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.02.048. discussion 5–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Soeterik TF, Veenboer PW, Lock TM. Electroejaculation in psychogenic anejaculation. Fertility and sterility. 2014;101:1604–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mulhall JP, Stahl PJ, Stember DS. Clinical care pathways in andrology. New York: Springer; 2014. [Google Scholar]