Abstract

Lassa virus protects its viral genome through the formation of a ribonucleoprotein complex in which the nucleoprotein (NP) encapsidates the single-stranded RNA genome. Crystal structures provide evidence that a conformational change must occur to allow for RNA binding. In this study, the mechanism by which NP binds to RNA and how the conformational changes in NP are achieved was investigated with molecular-dynamics simulations. NP was structurally characterized in an open configuration when bound to RNA and in a closed form in the absence of RNA. Our results show that when NP is bound to RNA, the protein is highly dynamic and the system undergoes spontaneous deviations away from the open-state configuration. The equilibrium simulations are supported by free-energy calculations that quantify the influence of RNA on the free-energy surface, which governs NP dynamics. We predict that the globally stable states are qualitatively in agreement with the observed crystal structures, but that both open and closed conformations are thermally accessible in the presence of RNA. The free-energy calculations also provide a prediction of the location of the transition state for RNA binding and identify an intermediate metastable state that exhibits correlated motions that could promote RNA binding.

Introduction

Lassa virus is a member of the Old World arenavirus family, which causes hemorrhagic fever (Lassa fever) in infected humans. Lassa is predominant in Western Africa, where it infects hundreds of thousands of people, resulting in 5000–10,000 human deaths annually (1, 2). There is no effective vaccine against Lassa (2) and it is the most frequently imported hemorrhagic fever from Africa to the United States and Europe (1, 3, 4). As Lassa is a major threat to public health, a critical step toward developing antiviral therapeutics and vaccines is to gain a detailed understanding of the structure-function relationships in the Lassa virion.

Lassa has a simple genome containing four genes, but it employs a complex ambisense coding strategy. The single-stranded (ss) negative-sense RNA genome consists of large (∼7 kb) and small (∼3.4 kb) segments (5). The large subunit encodes the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (L) and a zinc-binding (Z) protein, whereas the small segment encodes for a glycoprotein (GP), which is posttranslationally cleaved to form GP1 and GP2, and an RNA-binding nucleoprotein (NP). Before 2010, no high-resolution structures of any Lassa protein had been determined. In recent years, significant progress has been made in the structural characterization of the Lassa proteins, including structures of the Z protein (6), the N-terminal endonuclease domain of L (7), GP1 (8), and numerous structures of NP (9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14).

NP contains 569 residues and is composed of N- and C-terminal domains connected by a flexible linker. The N-terminal domain is the RNA-binding domain (9), and the C-terminal domain has double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) nuclease functionality (13). The full-length structure has been determined (11, 12), as have structures of just the N-terminal domain (13) and the C-terminal domain (9, 10). The domain-level structures are highly similar and topologically consistent with the full-length structures. NP has multiple roles in the Lassa life cycle, including binding the viral RNA to form ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes, which is required for transcription and replication (15). NP also has immunosuppressive activity related to its ability to degrade dsRNA in the C-terminal domain (13, 16).

Lassa NP binds RNA and contains a positively charged RNA-binding cavity in the N-terminal domain. The first structure determined for Lassa NP was for the full-length protein; however, the RNA-binding pocket could not be determined (11). In a subsequent study utilizing a C-terminal domain deletion mutant, an RNA-bound form of Lassa NP N-terminal domain was solved (9). The overall topology of the unbound (apo) and RNA-bound N-terminal domains was consistent, showing mainly α-helical secondary structural elements (Fig. 1). The major structural differences between the apo and RNA-bound forms were in the two helices close to the RNA-binding site. In the apo form, α helix 5 (α5, residues 97–122) is extended compared with the RNA-bound structure. The other major difference between the apo and RNA-bound structures was in the positioning of α helix 6 (α6, residues 131–145) relative to the RNA-binding groove. In the apo form (Fig. 1 A), α6 is aligned perpendicular to the binding groove and in close proximity to the groove, potentially blocking RNA entry to the binding pocket. In the RNA-bound form (Fig. 1 B), α6 is swung away from the binding groove, allowing RNA to enter and bind. The RNA-bound crystal structure asymmetric unit contained six subunits and α6 adopted different orientations in all subunits. In all of the subunit structures, α6 was spatially separated from the RNA-binding site in an open configuration.

Figure 1.

(A and B) Structure of the Lassa NP N-terminal domain in the closed (A) and open (B) states. These structures are derived from PDB ID: 3MWP (A) and 3T5Q.K (B). The open structure is bound by a six-base-long strand of RNA (purple). The major structural differences between the bound and unbound forms are in the positioning of α6 (red) and the disordering of a region of α5 (orange). To see this figure in color, go online.

One potential explanation for why full-length NP could not be crystalized in an RNA-bound state is associated with the oligomeric state of NP in the above studies. Multiple oligomeric states of the full-length protein have been detected (9), but based upon x-ray crystal structures (11, 12), small-angle x-ray scattering (12), sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation (17), and electron microcopy (12) experiments, a symmetric head-to-tail trimer of NPs appears to be the dominant oligomeric state in solution. It has been suggested that this trimeric self-association serves a function similar to that of the phosphoprotein in nonsegmented, negative strand viruses, in that it allows a buildup of NP without nonspecific RNA binding (9, 18). In the trimeric form, the NP RNA-binding site is presumed to be occluded due to positioning of α6 and a “gating loop” (residues 232–243) in the N-terminal domain (9). It is speculated that there may be coupling between the interdomain separation (or angle) and accessibility of the RNA-binding site, but direct evidence for this coupling is currently lacking. The trimer form may represent an early-stage RNP assembly intermediate that is disrupted as viral RNA replication proceeds and the concentration of viral RNA increases. Formation of the RNP is essential for viral transcription and RNA replication (19), and therefore understanding the initial RNA-NP interactions may provide new targets for developing antiviral therapies (8, 20).

Molecular modeling studies on Lassa have been limited by the lack of structural information, but recent studies have examined the Z protein (21) and NP (22, 23). The studies on NP involved calculations of binding between NP and m7GpppN cap (23) and RNA (22). In the earlier study, Li et al. (23) examined dTTP and m7GpppN binding to the closed conformation of NP to evaluate a proposed cap-snatching mechanism for priming mRNA synthesis (11). Using molecular-mechanics/generalized Born surface area (MM/GBSA) calculations (24), they predicted strong binding (−127 kcal/mol) of m7GpppN to NP. A strong binding interaction between NP and m7GpppN is not experimentally well established, and in fact there is evidence against this mechanism. A series of mutants in the RNA-binding pocket failed to generate a significant reduction in mRNA levels without a concomitant reduction in viral genome replication (12), and pull-down assays failed to show binding of NP to m7GTP (9). In a subsequent study by Zhang et al. (22), MM/GBSA was again used to evaluate RNA binding to NP. In that study, the open state was modeled with the use of a pepsin-digested structure that lacked coordinates for α6, and the closed-state structure (PDB ID: 3MWP) was used as a homology modeling template. This approach may have generated a conformation of NP in which the positioning of α6 was not as far removed from the RNA-binding pocket as is observed in the open-state crystal structure (PDB ID: 3T5Q). Therefore, what is presented as an open conformation may be quite similar to the closed-state structure. In that study, the RNA binding energy was evaluated between wild-type NP and two mutant NP variants that are known to knock down transcriptional activity. The mutants are predicted to bind RNA slightly more strongly than the wild-type NP, which would imply a more complicated mechanism than a simple weakening of the binding. Although the two studies may not be directly comparable, the m7GpppN binding energy (−127 kcal/mol) was predicted to be stronger than the RNA binding energy (−101 kcal/mol), which does not appear to be consistent with experimental studies.

In this investigation, we examined gating structural rearrangements in the N-terminal domain of NP and the mechanism of RNA binding. We employed molecular-dynamics (MD) simulations to explore the influence of RNA binding on the NP dynamics and energy landscape in both the open and closed configurations. In this work, we improved upon previous studies by employing pathway-based (metadynamics) methods in addition to end-point-based (MM/GBSA) methods, which can provide mechanistic insights. This study serves to enhance our knowledge of Lassa NP behavior through the application of multiple MD techniques and analyses to resolve the dynamic structure and interactions that arise when NP undergoes binding of viral RNA.

Materials and Methods

Model building

To generate complete models for the open-RNA-bound structure, we used the pepsin-digested structure NPpep (PDB ID: 3T5N) and modeled in missing segments. The coordinates of α6 (residues 128–145) were copied from the k monomer structure in PDB ID: 3T5Q. The loops adjacent to α6 (residues 113–127 and residues 146–163) were modeled into the structure using MODELER (25, 26). The structure for the closed-apo state was based upon the full-length structure (PDB ID: 3MWP). Residues 148–157 were modeled using MODELER. The open-apo structure was created by taking this open-RNA-bound structure and removing the RNA atoms. The closed-RNA structure was built by aligning the closed-apo and open-RNA-bound structures along the RNA-contacting residues (9) and then copying in the RNA coordinates. Additional models for the open-RNA conformation were constructed in the same manner, except that the coordinates of α6 were extracted from the A or G monomers in 3T5Q. The sequences of RNA used in these simulations are consistent with the RNA sequence in the crystal structure (PDB ID: 3T5Q), which is UAUCUC. This RNA sequence was used in all RNA simulations except for the simulation using the α6 position of the A monomer, which had more bases resolved in the crystal structure. The sequence in the A monomer simulation is UUAUCUCA.

Equilibrium MD

MD simulations were performed using the GROMACS 4.6.1 simulation package (27) and the CHARMM27 force field (28, 29). Systems were solvated in a cubic box with the CHARMM TIP3P water model, with Lennard-Jones parameters for the hydrogen atoms and 150 mM NaCl. The system sizes were ∼68,000 atoms for the open NP systems and ∼61,000 atoms for the closed NP systems. The systems were energy minimized for 5000 steps using the steepest-descent algorithm while the positions of the nonhydrogen (heavy) atoms of the protein and RNA were restrained with a force constant of 1000 kJ/mol/nm2. The position restraints were released and the system was minimized for another 5000 steps of steepest descent. Subsequently, the systems were restrained in the same manner as described for energy minimization, and 100 ps of NVT (300 K) followed by 100 ps of NPT (300 K, 1 atm) equilibration were run. Production MD simulations were performed in the NPT ensemble at 300 K and 1 atm using a Parrinello-Rahman barostat and a velocity-rescale thermostat (30). Coupling time constants of 1 ps were used for both the temperature and pressure coupling. A switching function was applied to the Lenard-Jones forces at 10 Å, with a cutoff at 12 Å. Long-range electrostatics (>12 Å) were computed by using the particle mesh Ewald method with a Fourier spacing of 1 Å. The trajectories were computed using the leap-frog stochastic dynamics integrator with a time step of 2 fs. Waters were kept rigid using the SETTLE algorithm (31), and nonwater bonds involving hydrogen atoms were constrained with the LINCS algorithm (32). The open-RNA, open-apo, and closed-apo systems were simulated for 250 ns, and the closed-RNA system was simulated for 150 ns.

We performed principle component analysis (PCA) on the equilibrium simulations to identify dominant motions, which allowed us to analyze the dynamics in a reduced basis set. For the PCA, we constructed a covariance matrix (Cij) of the protein backbone atom positions using the GROMACS g_covar tool and simulation snapshots taken every 1 ps. The covariance matrices are given by

| (1) |

where x1, …,x3N are the mass-weighted Cartesian coordinates of the N backbone atoms, and 〈〉 indicates averaging over the snapshots extracted from the simulations (e.g., time averaging). The eigenvectors and eigenvalues of Cij can be determined by standard linear algebra methods; each eigenvector represents a direction of motion of the system and is termed a principal component (PC). The PCs with the largest eigenvalues capture the most variance (motion) and thus are considered the global motions. It is often observed that analyzing just a few PCs will capture the majority of motion of the system, as well as functionally relevant motions, and therefore is an effective technique for reducing dimensionality (33, 34). We determined the eigenvectors of our covariance matrices using the GROMACS g_aneig tool. We computed the PCA free-energy surfaces (FESs) by projecting the equilibrium trajectories at 1 ps frequency onto the first two PCs and then Boltzmann inverting the probability density into a free energy (F = –kBTln(P)).

Free-energy calculations

The Plumed 1.3 plugin (35) with GROMACS 4.6.2 was used to perform well-tempered metadynamics (36). The collective variable (CV) that was biased on the metadynamics simulations was the mean-squared displacement (MSD) of the α6 Cα atoms measured with reference to the closed-apo structure. A Gaussian width of 0.05 nm2 and a height of 0.3 kcal/mol were used. A harmonic upper wall was placed at 4.0 nm2 from the closed state, with a spring constant of 5000 kJ/mol/nm4.

We examined the correlated dynamics from the metadynamics trajectories by splitting the trajectory into segments based upon the value of the CV. We then analyzed the correlated dynamics by constructing dynamic cross-correlation matrices (DCCMs) on the subtrajectories using the Bio3d package (37).

MM/GBSA calculations were performed to analyze the energetics of the crystal contacts. The unit cell tool in Chimera (38) was used to display all of the NPs in the unit cell, using the P6 symmetry of the crystal lattice. A tetramer in which three NPs contacted α6 of a fourth NP was selected for analysis. A 35 ns simulation of the tetramer in explicit solvent was performed in GROMACS. The MM/GBSA analysis was performed in the CHARMM simulation package (version c38) (39) using the CHARMM27 force field on the last 30 ns of the tetramer. Snapshots were extracted every 100 ps, for a total of 300 analysis frames. Full-equilibrium simulations were used for the MM/GBSA calculation of monomer opening and RNA binding, and frames were extracted every 100 ps for these calculations as well. The binding energy was calculated from the following equation:

| (2) |

where EMM is the molecular-mechanics gas-phase energy, GGB is the polar solvation free energy calculated by the generalized-Born formalism, and GNP is the nonpolar solvation free energy. GGB was calculated using the GBSW implicit solvent model (40) with a smoothing length of 0.3 Å, a nonpolar surface tension coefficient of 0.03 kcal/mol/Å2, and a salt concentration of 150 mM. The nonpolar surface area was calculated as GNP = γ(surface area) + b, where we take γ = 0.00542 and b = 0.92 (41). The surface area was determined from the solvent-accessible surface area using a probe radius of 1.4 Å.

Results and Discussion

NP equilibrium simulations

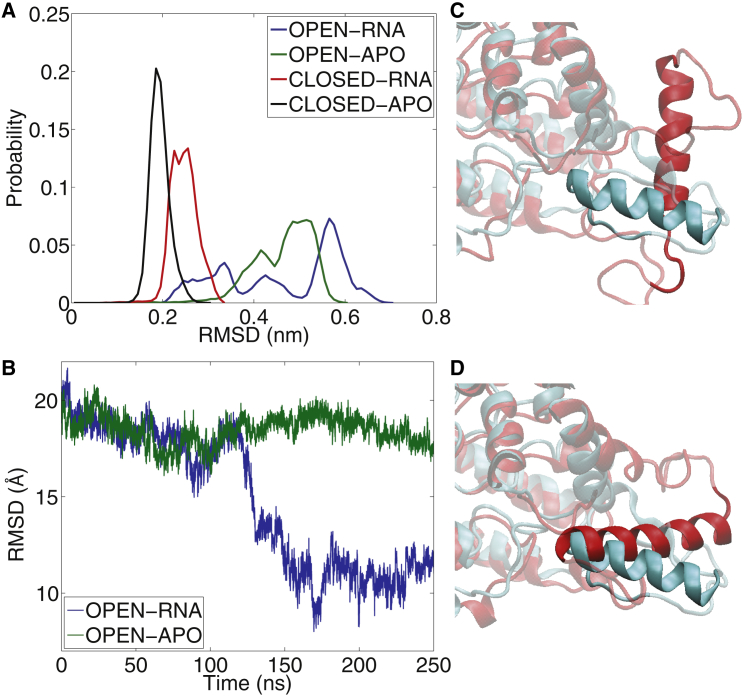

We initiated our study by evaluating the equilibrium dynamics of the open and closed conformations in both the presence and absence (apo) of RNA. Therefore, we examined four systems: open-RNA (Fig. 1 B), open-apo, closed-RNA, and closed-apo (Fig. 1 A). MD simulations for all four systems were conducted for at least 150 ns, and the distributions of backbone root mean-square deviation (RMSD) values for the four simulations are shown in Fig. 2 A. The closed-apo simulation was the most stable, undergoing a maximum 3.1 Å deviation. Somewhat surprisingly, the closed-RNA simulation was the second most stable, displaying a maximum RMSD of 3.5 Å. Given that the RNA-bound form is in an open configuration in the crystal structure, we expected to see larger structural changes and possibly a transition to the open state when α6 was started in close proximity to the RNA.

Figure 2.

Equilibrium dynamics. (A) Probability distributions in RMSD, calculated over the backbone atoms after least-squares alignment to each simulation’s respective starting structure. (B) Cα RMSD of α6 for the open-state simulations, calculated after a global alignment to the closed-apo state. (C and D) Comparison of the open-RNA (red) and closed-apo (cyan) α6 positions at the beginning (C) and end (D) of the 250 ns open-RNA simulation. To see this figure in color, go online.

The open-state simulations showed NP to be considerably more dynamic than what was observed in the closed-state simulations. The increased structural dynamics are reflected by maximum RMSDs of 6.2 Å and 7.1 Å in the open-apo and open-RNA simulations, respectively. The observation that the open structures are more dynamic is consistent with the x-ray structure, where α6 adopts significantly different orientations in each of the six-subunit structures within the asymmetric unit. However, the nature of the dynamics was unanticipated, especially in the open-RNA case. We examined whether the open simulations made a transition toward the closed state, and found that the open-RNA did transition toward the closed structure at ∼120 ns, but the open-apo remained in the open configuration (Fig. 2 B). Overlays of the closed state with the initial open-RNA and final open-RNA structures are shown in Fig. 2, C and D, respectively. It can be seen that α6 rotates by ∼90° and the C-terminal end of α6 adopts a position in close proximity to the RNA-binding groove, in a manner highly similar to the closed-state positioning.

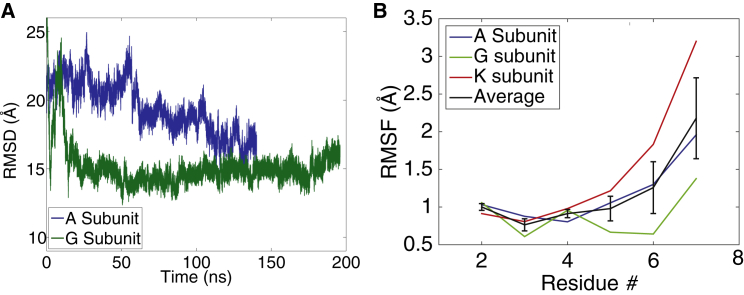

There are six subunits in the RNA-bound crystal structure (PDB ID: 3T5Q) (9). The simulations discussed above were initiated from the K-subunit structure. To assess whether the closing motion we observed was dependent on the initial conditions of the simulation (or a spurious fluctuation), we performed two additional simulations in which the RNA-bound system was initiated in a different open configuration. We ran simulations of the A subunit for 140 ns and the G subunit for 195 ns. In both cases, α6 moves closer to the closed conformation (Fig. 3 A), changing from >20 Å, to ∼15 Å. The degree of closing is not as drastic as that observed for the K-subunit (Fig. 2 B); however, in all three simulations the system adopts a more closely packed structure than is observed in the crystal structure. We compared the A, G, and K open-state simulations on the same phase space of the first two PCs of the K subunit (Fig. S1 A in the Supporting Material). We found that the A and G subunits sampled the same phase space as K did during the later part of the K simulations, indicating that all three subunits ended up with similar dynamics. However, the K subunit started in a different region of the PC space, which was not sampled by the A and G subunits, likely due to the different orientations of α6 in the different subunits (Fig. S1 B). We will further discuss this point in light of the free-energy calculations presented below.

Figure 3.

Lassa NP and RNA structural dynamics in the open-RNA-bound state. (A) α6 RMSD after global alignment to the closed state (same as Fig. 2B) for simulations started from the A and G subunit structures from PDB ID: 3T5Q. (B) RNA RMSF for the subunit simulations and also averaged over the three RNA-bound simulations (subunits A, G, and K). To see this figure in color, go online.

RNA equilibrium dynamics

The binding of NP to RNA is thought to be nonspecific, given that the RNA-bound structure was crystalized with random, cellular RNA. However, in all six subunits of the crystal structure, the third RNA position was always a purine residue (9). In the other RNA positions, except for position 8, the nucleotide could not be unambiguously determined. The eighth position was also purine, but not all subunits contained the eighth nucleotide. This observation led to the speculation that there may be a partial sequence specificity governing the NP-RNA binding process. Our simulations are supportive of a partial specificity, as we observe variable structural fluctuations of the RNA positions in our simulations of the A, G, and K subunits. The most stable position is position 3 (Fig. 3 B), consistent with the experimental observation that position 3 may be a high-affinity site for binding purine residues. However, this result may be a consequence of the structure determination process. By having a better-resolved electron density at the third position, the atomic positions of that base may be at higher resolution, resulting in increased stabilization at that position during the MD simulations.

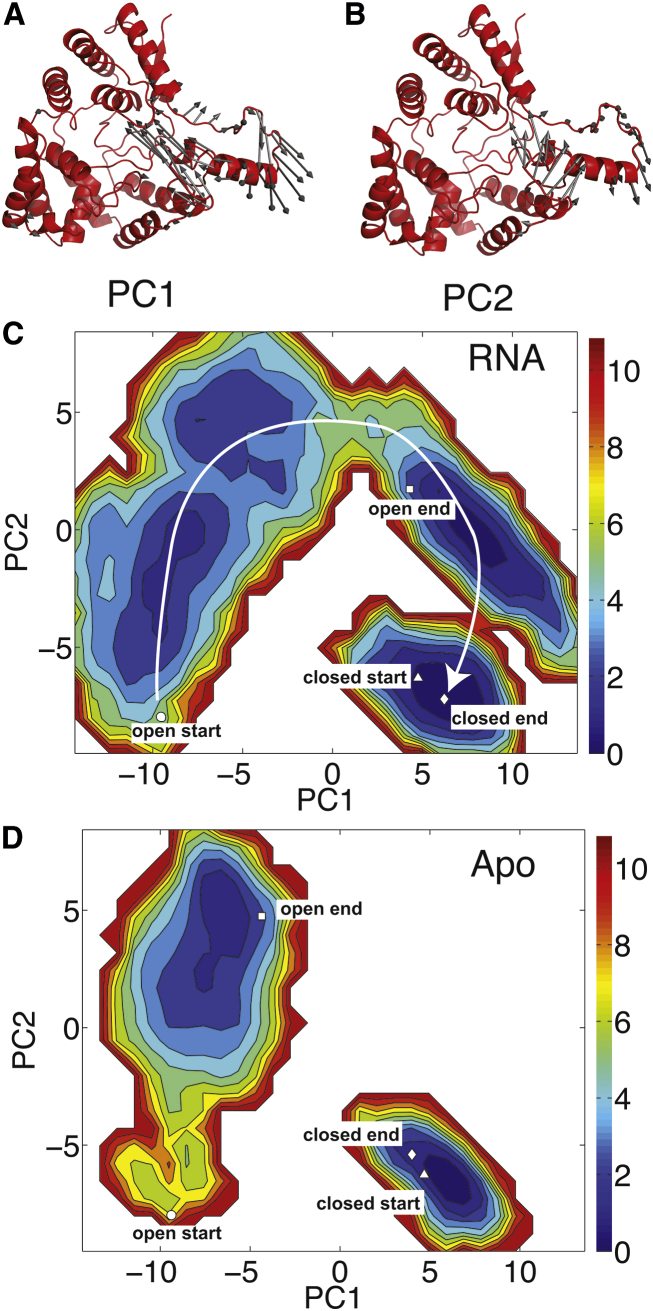

PCA

To analyze the global dynamics of the open and closed states, we performed PCA. The two PC modes that captured the most variance (PC1 and PC2) were determined for the simulations initiated in the known crystallographic states (open-RNA and closed-apo). Mode projections were performed for all four simulations, and then the RNA-bound simulations were combined to generate a pseudo-FES in the PC degrees of freedom. Similarly, the apo simulations were combined to generate an apo FES. The open-RNA modes are presented in Fig. 4, A and B. The dominant motions in both PC1 and PC2 involve twisting of α6. PC1 is a lateral twisting of α6 and its adjacent loops, whereas PC2 is a rotation of the helix in which the N-terminal loop is moving upward while the C-terminal loop is moving downward and inward. The energy surface when RNA is bound (Fig. 4 C) shows a contiguous energy surface, indicating that large energy barriers do not separate the open and closed states. A transition pathway of closing can be inferred from the energy surface (as indicated by the arrow). To move along this transition path, the system would move positively along PC2, followed by positive movement along PC1, followed by negative movement along PC2 to reach the closed configuration. In contrast, the apo surface is discontinuous (Fig. 4 D), indicating that an energy barrier separates the open and closed states; therefore, this transition was not sampled in the equilibrium simulations.

Figure 4.

PCA of open-RNA dynamics. (A and B) Modes 1 and 2 are imposed on the open-state structure, where the arrows represent positive motion in the mode direction. (C and D) Pseudo-free surfaces of the RNA-bound and apo simulations projected on the modes shown in (A) and (B). The start and end points of the simulations are indicated by the white symbols: the open-state simulation begins at the circle and ends at the square, and the closed-state simulation begins at the triangle and ends at the diamond. To see this figure in color, go online.

An analogous analysis was performed using the PCs from the closed-apo simulations, which are presented in Fig. S2. Although in this case the open- and closed-state simulations overlap for both the RNA-bound and apo simulations, there is a lower barrier separating the open and closed states when RNA is bound, which is qualitatively consistent with the open-RNA PCA.

Metadynamics

We employed well-tempered metadynamics (36) to evaluate the free-energy landscape governing the mobility of α6. The CV we biased in the metadynamics simulations was the MSD of α6 from the closed conformation. Metadynamics was performed for 300 ns for the apo system and 370 ns for the RNA-bound system, which produced well-converged FESs (see Figs. S3 and S4). The converged FESs are presented in Fig. 5 A and structures along the binding pathways are shown in Fig. 5 B. The apo energy surfaces show that the closed state is separated from the open state by ∼15 kcal/mol. The presence of RNA has a drastic effect in flattening the landscape. The open state is still the global minimum, but the energy separation between open and closed is <1 kcal/mol, which would allow for a subpopulation of closed states to exist at physiological temperatures. There is a crossing in the energy surfaces at ∼9 Å, which provides a prediction of the transition-state structure that would bind RNA. In the apo metastable state just before the crossing (Fig. 5 B, structure II), the gating loop (residues 232–243) is in an up position, occluding the binding site. As α6 moves further toward the open state, we observe that the gating loop moves down to allow accessibility to the binding groove.

Figure 5.

FES of Lassa NP α6 opening. (A) FESs obtained from well-tempered metadynamics in the absence (apo) and presence of RNA. (B) Stable and transition-state structures along the transition pathways. The structures were determined by partitioning the metadynamics simulations into subspaces in the CV space. The average structure in each subspace was determined and the presented structures are those with the smallest RMSD from the average structures. α6 is blue, RNA is yellow, and the gate loop (residues 232–243) is red. Below each structure are DCCMs from the same regions of the metadynamics CV space. State I: Apo RMSD 0–5.5 Å; state II: Apo RMSD 7–8.6 Å; state III: RNA bound RMSD 8–9.2 Å; state IV: RNA bound RMSD 14–15.3 Å. The vertical black lines in the DCCMs outline the α6 residues. X and Y axes in the DCCMs in units of residue number, and the scale bar in state IV applies to all plots. To see this figure in color, go online.

The metadynamics FES provides explanations for several observed behaviors of the various systems in equilibrium MD. The flattened energy surface in the presence of RNA explains why spontaneous closing motions are observed in the equilibrium simulations (Figs. 2 B and 3 A). Furthermore, the open-apo simulation did not transition to the closed configuration, which may be due to the energy barrier at ∼15 Å. The large RMSDs (Fig. 2 A) in the open-state equilibrium MD simulations are consistent with the flat energy landscape in the regions beyond ∼15 Å on FES. In contrast, the FES near the closed conformation (<5 Å) displays well-defined energy minima that restrict the conformational dynamics, resulting in low RMSDs in the equilibrium simulations.

We examined the correlated motions for several states of the system along the RNA-binding pathway. Here, we consider the apo global minimum state (state I, Fig. 5 B), the apo metastable state before RNA binding (state II, Fig. 5 B), the transition state with RNA bound (state III, Fig. 5 B), and the RNA global minimum (state IV, Fig. 5 B). The DCCMs for these four states are presented in Fig. 5 B. In the apo minimum energy state (state I) the system does not show significant correlations, but as it moves to the metastable state (state II), significant correlated motions become present. In particular, α6 develops a strong anticorrelation with regions surrounding the RNA-binding groove, which can be interpreted as expansion and contraction motions. Anticorrelated motions surrounding the RNA-binding site are not a unique feature of the Lassa NP; this behavior has also been observed in several viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (42, 43). Once the RNA strand binds NP (state III), the correlations remain strong throughout the protein, but the correlations between α6 and the rest of the protein are diminished and display positive correlations as well. When the system reaches the stable RNA-bound state (state IV), the correlations are diminished throughout the protein, and the protein exhibits correlations that are most similar to the apo minimum-energy state. This presents a mechanism in which the apo protein transitions to the excited metastable state where α6 becomes strongly (anti)correlated with regions of the protein, promoting fluctuations that increase access to the binding groove to allow RNA to bind.

Another change in the DCCM between state III and state IV is found in the correlations between residues 50–70. These residues are part of helices 3 and 4, which lie below the RNA-binding groove. There are anticorrelated motions between this region and residues 150–160, which are on strand 11, which connects to α6. There are contacts between strand 11 and the tips of α3 and α4 in state III, which become disrupted in state IV. These contacts act to restrict the mobility of α6 and excite anticorrelated motions. The positioning of α6 and the correlated motions between this region and α3 and α4 may be important for facilitating entry of RNA into the binding groove.

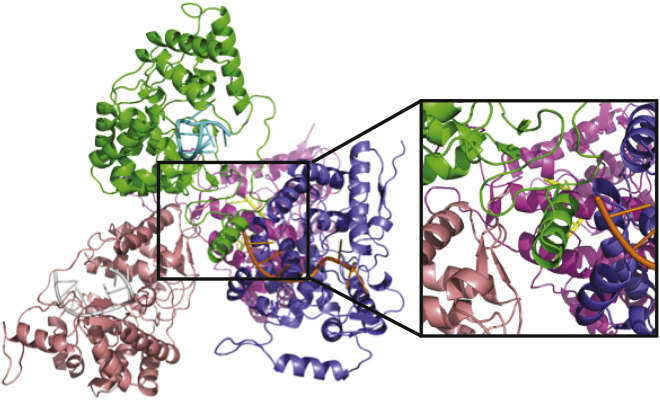

Crystal-contact analysis

The minimum-energy states in the apo and RNA-bound metadynamics simulations roughly correspond to the known crystal structures. However, we observe that the RNA-bound state is more closed in the presence of RNA than is observed in the crystal structure. The RMSD values of the α6 configurations (after global alignment) in the crystal structure compared with the closed configuration range from 23.4 to 26.1 Å, whereas our global minimum is significantly shifted inward to ∼15 Å. Furthermore, given the propensity of α6 to undergo closing motions in the equilibrium simulations, we examined the energetics of nonnative contacts in the crystal structure to understand their role in stabilizing the open conformation.

Based upon inspection of the open-state crystal structure (PDB ID: 3T5Q), significant contacts between α6 from various subunits and neighboring proteins can be observed. To quantify the strength and favorability of these interactions, we performed an MM/GBSA calculation to measure the binding affinity of α6 from subunit I to the interface created by neighboring subunit A within the same asymmetric unit and the A and G subunits from a neighboring asymmetric unit (Fig. 6). Based upon the MM/GBSA calculation, a binding energy of −245.51 kcal/mol was found. This protein-protein binding energy is certainly an overestimate given that the entropy loss is not considered here, as was done in another crystal-contact study (44). To provide a basis for comparison, we also performed MM/GBSA on the RNA binding to the open and closed states, as well as the opening transition in the absence and presence of RNA. The results are presented in Table 1. These calculations support the notion that the crystal-contact energies are significant and have the potential to alter the conformational state of the protein. Furthermore, these calculations show that spontaneous opening of the apo protein is unfavorable (ΔG = 164.21 kcal/mol), which is consistent with our metadynamics FES, but that RNA binding (ΔG = −143.39 kcal/mol) alone is not sufficient to overcome the unfavorable opening energy. The additional favorable interaction of the open state with the neighboring subunits could provide the additional energy required to stabilize the open-RNA-bound state.

Figure 6.

Contacts between α6 of monomer I (green) and neighboring subunits in the crystal structure (PDB ID: 3T5Q). To see this figure in color, go online.

Table 1.

MM/GBSA Evaluation of RNA-Protein and Protein-Protein Interactions

| RNA Binding |

NP Opening |

Protein-Protein Binding | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP Open | NP Closed | APO | RNA Bound | ||

| <ΔEMM> | −1290.93 | −1158.28 | 252.92 | 120.27 | −747.73 |

| <ΔGGB> | 1157.50 | 1138.88 | −91.13 | −72.51 | 522.17 |

| <ΔGNP> | −9.96 | −9.96 | 2.42 | 3.96 | −19.8356 |

| <ΔGbind> | −143.39 | −29.36 | 164.21 | 51.72 | −245.40 |

MM-GBSA calculations for RNA binding to open and closed conformations of the NP, opening of the NP in the presence and absence (apo) of RNA, and binding of monomer I to neighbor subunits in the crystal structure. All units are in kcal/mol.

Conclusions

Using extensive MD simulations, we have described the influence of RNA binding on the structure and dynamic properties of the Lassa NP. We have shown that the energy landscape in the presence of RNA is much flatter with respect to the α6 position. This implies that α6 will sample a wide range of conformations that may be important in mediating interactions with other viral proteins, including other NPs. Indeed, other negative-sense, single-stranded RNA viruses are known to have small, mobile helical elements that undergo conformational changes to switch between RNA binding and nonbinding modes (45). The dynamics of α6 may also be important for understanding the interaction between NP and the L protein, which is part of the RNP. Transient exposure of RNA due to fluctuations in the α6 position may provide an opportunity for L to engage with the RNA and induce further conformational changes in the NP to allow for replication or transcription to proceed.

In addition to gaining insight into the influence of RNA on the stability of the known conformational states, we were able to detect an intermediate structure along the RNA-binding pathway. A metastable state exists when α6 is displaced from the closed configuration by ∼8 Å in RMSD space. In the metastable configuration, NP develops strong correlated motions between various regions of the protein, and, importantly, anticorrelated motions develop between α6 and several helices surrounding the RNA-binding groove. These anticorrelated motions would allow for the binding crevice to expand, pushing NP toward the transition state where it would bind to the RNA strand. Binding to RNA would then induce further movement of α6 out to ∼15 Å, where the system would stabilize and correlated motions would be suppressed. When bound to RNA, α6 is expected to sample many conformations but to exist primarily in a more closed form than is experimentally observed. We rationalize this difference as being due to the favorable interactions between α6 and neighboring NP proteins in the crystal lattice, which would likely be absent in solution.

Author Contributions

J.G.P. and E.R.M. designed the simulations, carried out the simulations, analyzed results, and wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank James Cole for reading and providing helpful comments on the manuscript.

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (K22AI099163) and internal funding from the University of Connecticut. Computational resources were provided through the University of Connecticut Booth Center for Advanced Technology and the National Science Foundation XSEDE program (allocation No. TG-MCB140016).

Editor: Michael Feig.

Footnotes

Four figures are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(16)00151-X.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Haas W.H., Breuer T., Günther S. Imported Lassa fever in Germany: surveillance and management of contact persons. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003;36:1254–1258. doi: 10.1086/374853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Falzarano D., Feldmann H. Vaccines for viral hemorrhagic fevers—progress and shortcomings. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2013;3:343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macher A.M., Wolfe M.S. Historical Lassa fever reports and 30-year clinical update. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006;12:835–837. doi: 10.3201/eid1205.050052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holmes G.P., McCormick J.B., Fisher-Hock S.P. Lassa fever in the United States. Investigation of a case and new guidelines for management. N. Engl. J. Med. 1990;323:1120–1123. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199010183231607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yun N.E., Walker D.H. Pathogenesis of Lassa fever. Viruses. 2012;4:2031–2048. doi: 10.3390/v4102031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Volpon L., Osborne M.J., Borden K.L.B. Structural characterization of the Z RING-eIF4E complex reveals a distinct mode of control for eIF4E. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:5441–5446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909877107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallat G.D., Huang Q., Dong C. High-resolution structure of the N-terminal endonuclease domain of the Lassa virus L polymerase in complex with magnesium ions. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen-Dvashi H., Cohen N., Diskin R. Molecular mechanism for LAMP1 recognition by Lassa virus. J. Virol. 2015;89:7584–7592. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00651-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hastie K.M., Liu T., Saphire E.O. Crystal structure of the Lassa virus nucleoprotein-RNA complex reveals a gating mechanism for RNA binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:19365–19370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108515108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hastie K.M., King L.B., Saphire E.O. Structural basis for the dsRNA specificity of the Lassa virus NP exonuclease. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44211. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qi X., Lan S., Dong C. Cap binding and immune evasion revealed by Lassa nucleoprotein structure. Nature. 2010;468:779–783. doi: 10.1038/nature09605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brunotte L., Kerber R., Günther S. Structure of the Lassa virus nucleoprotein revealed by X-ray crystallography, small-angle X-ray scattering, and electron microscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:38748–38756. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.278838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hastie K.M., Kimberlin C.R., Saphire E.O. Structure of the Lassa virus nucleoprotein reveals a dsRNA-specific 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity essential for immune suppression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:2396–2401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016404108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang X., Huang Q., Dong C. Structures of arenaviral nucleoproteins with triphosphate dsRNA reveal a unique mechanism of immune suppression. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:16949–16959. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.420521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hass M., Gölnitz U., Günther S. Replicon system for Lassa virus. J. Virol. 2004;78:13793–13803. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.24.13793-13803.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reynard S., Russier M., Baize S. Exonuclease domain of the Lassa virus nucleoprotein is critical to avoid RIG-I signaling and to inhibit the innate immune response. J. Virol. 2014;88:13923–13927. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01923-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lennartz F., Hoenen T., Garten W. The role of oligomerization for the biological functions of the arenavirus nucleoprotein. Arch. Virol. 2013;158:1895–1905. doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1684-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruigrok R.W., Crépin T., Kolakofsky D. Nucleoproteins and nucleocapsids of negative-strand RNA viruses. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2011;14:504–510. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pinschewer D.D., Perez M., de la Torre J.C. Role of the virus nucleoprotein in the regulation of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus transcription and RNA replication. J. Virol. 2003;77:3882–3887. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.6.3882-3887.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee K.J., Novella I.S., de La Torre J.C. NP and L proteins of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) are sufficient for efficient transcription and replication of LCMV genomic RNA analogs. J. Virol. 2000;74:3470–3477. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.8.3470-3477.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.May E.R., Armen R.S., Brooks C.L., 3rd The flexible C-terminal arm of the Lassa arenavirus Z-protein mediates interactions with multiple binding partners. Proteins. 2010;78:2251–2264. doi: 10.1002/prot.22738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y., Chen H., Han J.-G. Insight into the binding modes of Lassa nucleoprotein complexed with ssRNA by molecular dynamic simulations and free energy calculations. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2015;33:946–960. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2014.923785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li L., Li D., Han J.-G. Studies on the binding modes of Lassa nucleoprotein complexed with m7GpppG and dTTP by molecular dynamic simulations and free energy calculations. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2013;31:299–315. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2012.703061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Genheden S., Ryde U. The MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods to estimate ligand-binding affinities. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2015;10:449–461. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2015.1032936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fiser A., Do R.K.G., Šali A. Modeling of loops in protein structures. Protein Sci. 2000;9:1753–1773. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.9.1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sali A., Blundell T.L. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;234:779–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hess B., Kutzner C., Lindahl E. GROMACS 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008;4:435–447. doi: 10.1021/ct700301q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mackerell A.D., Jr., Feig M., Brooks C.L., 3rd Extending the treatment of backbone energetics in protein force fields: limitations of gas-phase quantum mechanics in reproducing protein conformational distributions in molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1400–1415. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foloppe N., Mackerell A.D., Jr. All-atom empirical force field for nucleic acids: I. Parameter optimization based on small molecule and condensed phase macromolecular target data. J. Comput. Chem. 2000;21:86–104. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bussi G., Donadio D., Parrinello M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 2007;126:014101. doi: 10.1063/1.2408420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miyamoto S., Kollman P.A. SETTLE: an analytical version of the SHAKE and RATTLE algorithm for rigid water models. J. Comput. Chem. 1992;13:952–962. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hess B., Bekker H., Berendsen H. LINCS: a linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 1997;18:1463–1472. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stein S., Loccisano A.E., Firestine S.M. Principal components analysis: a review of its application on molecular dynamics data. Annu. Rep. Comput. Chem. 2006;2:233–261. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maisuradze G.G., Liwo A., Scheraga H.A. Principal component analysis for protein folding dynamics. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;385:312–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonomi M., Branduardi D., Parrinello M. PLUMED: a portable plugin for free-energy calculations with molecular dynamics. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2009;180:1961–1972. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barducci A., Bussi G., Parrinello M. Well-tempered metadynamics: a smoothly converging and tunable free-energy method. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008;100:020603. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.020603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grant B.J., Rodrigues A.P.C., Caves L.S.D. Bio3d: an R package for the comparative analysis of protein structures. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2695–2696. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pettersen E.F., Goddard T.D., Ferrin T.E. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brooks B.R., Brooks C.L., 3rd, Karplus M. CHARMM: the biomolecular simulation program. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;30:1545–1614. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Im W., Lee M.S., Brooks C.L., 3rd Generalized Born model with a simple smoothing function. J. Comput. Chem. 2003;24:1691–1702. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sitkoff D., Sharp K.A., Honig B. Accurate calculation of hydration free energies using macroscopic solvent models. J. Phys. Chem. 1994;98:1978–1988. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moustafa I.M., Shen H., Cameron C.E. Molecular dynamics simulations of viral RNA polymerases link conserved and correlated motions of functional elements to fidelity. J. Mol. Biol. 2011;410:159–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.04.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davis B.C., Thorpe I.F. Thumb inhibitor binding eliminates functionally important dynamics in the hepatitis C virus RNA polymerase. Proteins. 2013;81:40–52. doi: 10.1002/prot.24154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ahlstrom L.S., Miyashita O. Packing interface energetics in different crystal forms of the λ Cro dimer. Proteins. 2013;82:1128–1141. doi: 10.1002/prot.24478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferron F., Li Z., Lescar J. The hexamer structure of Rift Valley fever virus nucleoprotein suggests a mechanism for its assembly into ribonucleoprotein complexes. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002030. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.