Abstract

Sites that display recurrent, aberrant DNA methylation in cancer represent potential biomarkers for screening and diagnostics. Previously, we identified hypermethylation at the ZNF154 CpG island in 15 solid epithelial tumor types from 13 different organs. In this study, we measure the magnitude and pattern of differential methylation of this region across colon, lung, breast, stomach, and endometrial tumor samples using next-generation bisulfite amplicon sequencing. We found that all tumor types and subtypes are hypermethylated at this locus compared with normal tissue. To evaluate this site as a possible pan-cancer marker, we compare the ability of several sequence analysis methods to distinguish the five tumor types (184 tumor samples) from normal tissue samples (n = 34). The classification performance for the strongest method, measured by the area under (the receiver operating characteristic) curve (AUC), is 0.96, close to a perfect value of 1. Furthermore, in a computational simulation of circulating tumor DNA, we were able to detect limited amounts of tumor DNA diluted with normal DNA: 1% tumor DNA in 99% normal DNA yields AUCs of up to 0.79. Our findings suggest that hypermethylation of the ZNF154 CpG island is a relevant biomarker for identifying solid tumor DNA and may have utility as a generalizable biomarker for circulating tumor DNA.

CME Accreditation Statement: This activity (“JMD 2016 CME Program in Molecular Diagnostics”) has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) through the joint providership of the American Society for Clinical Pathology (ASCP) and the American Society for Investigative Pathology (ASIP). ASCP is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

The ASCP designates this journal-based CME activity (“JMD 2016 CME Program in Molecular Diagnostics”) for a maximum of 36 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should only claim credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

CME Disclosures: The authors of this article and the planning committee members and staff have no relevant financial relationships with commercial interests to disclose.

One in four deaths in the United States is due to cancer, despite an emphasis on prevention, early detection, and treatment that has lowered cancer death rates by 20% in the past two decades.1, 2 Further improvements in survival rates are likely to come from improving the limits of detection sensitivity at earlier stages of cancer. Currently, a diagnosis results from a cadre of screening and diagnostic tools that may include physical examination, radiographic imaging, sputum cytologic testing, blood tests, endoscopy, and/or biopsies. However, new approaches that rely heavily on genomic information may change future testing strategies.

The future looks bright because minimally invasive sampling techniques coupled with genomic features that distinguish tumor cells from normal cells have the potential to detect cancer at earlier stages. For example, circulating tumor cells or cell-free plasma DNA can be detected in venous peripheral blood and tested for the presence of common mutations.3 Cell-free tumor DNA can also be detected in buccal epithelium, saliva, urine, stools, and bronchial aspirates.4 Such DNA has been used to detect mutations in patients with both localized and metastatic cancers.5 Moreover, somatic mutations in ovarian and endometrial cancers can potentially be detected using Papanicolaou specimens.6

In addition to genetic mutations, epigenetic markers are emerging as tools with discriminatory power for disease detection. For example, DNA methylation is a robust epigenetic marker for which a number of commercially available tests have been developed. These tests detect tissue-specific DNA methylation using clinical specimens and are used in colorectal cancer (SEPT9, blood; VIM, stool), lung cancer (SHOX2, bronchial fluid), and brain cancer (MGMT, tumor).7 One advantage of this approach is marker stability under common storage conditions.4 However, despite DNA methylation's potential as a diagnostic marker, a general lack of consensus on the methods remains. This is the principal reason for its slow implementation in clinical diagnostics.4, 7

Previously, our laboratory reported a pan-cancer hypermethylation signal around a CpG island near human ZNF154.8 This signal was initially detected by us in ovarian and endometrial cancers and replicated by us in multiple, independent cohorts from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), incorporating a total of 15 distinct tumor collections from 13 different organs with almost 6000 samples.8 These previous analyses relied on data generated from Illumina Infinium methylation arrays (Illumina Inc, San Diego, CA) to detect the methylation levels at select CpG sites. In this study, we measure the ZNF154 methylation signal across five tumor types using bisulfite amplicon sequencing. With this method, individual sequence reads are used to quantitate methylation levels of all CpGs within the amplicon while providing quantitative data for each DNA molecule in the pooled sample. Furthermore, the approach provides an intrinsic measure of quality control by tracking bisulfite conversion efficiency at cytosines in the non-CpG context wherein extensive amounts of unconverted cytosines signal an incomplete conversion reaction. This procedure is both time efficient and cost-effective because multiple samples can be sequenced in parallel using a 96-well plate and, as we report, generate reproducible measurements when assayed in independent experiments. The amplicon sequencing provides greater resolution of a target region than a methylation array by covering all amplified CpGs, revealing patterns of DNA methylation useful for distinguishing tumor from normal samples.

We report that the magnitude and reproducibility of the ZNF154 hypermethylation signal across five solid tumor types reinforces the potential of this site as a biomarker for circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA). Next, we assess the potential application of various computational data classification methods toward cancer screening. By investigating a variety of technical approaches to characterize methylated bases within the sequenced samples, we identify features useful for distinguishing tumor samples from normal samples. Finally, we use a computational simulation to demonstrate the utility of these features in classifying samples as tumor or normal tissue at various abundance levels; here, tumor DNA methylation patterns are compiled into a background of normal DNA methylation patterns, at limiting dilution levels, mimicking the fractions at which ctDNA is recovered from blood.

Materials and Methods

Sample Preparation

GM12878 and K562 Cell Lines

GM12878 is a lymphoblastoid cell line with a relatively normal karyotype and low DNA methylation levels. It was obtained from the Coriell Institute for Medical Research (catalog no. GM12878; Camden, NJ). K562 is an immortalized chronic myelogenous leukemia cell line. It has high methylation levels compared with GM128788 and was obtained from the ATCC (catalog no. CCL-243; Manassas, VA). Genomic DNA from GM12878 cells and K562 cells was harvested in triplicate using the QiaAmp DNA Mini Kit (catalog no. 51304), and DNA from each replicate was serially diluted to 100, 50, and 20 ng of total starting material, in duplicate (thus yielding 18 replicate samples per cell line). During the bisulfite conversion step, nine samples failed, wherein six were generated from the 100-ng dilutions.

Gynecologic Samples

The Cooperative Human Tissue Network, funded by the National Cancer Institute, provided eight normal endometrial tissue samples. DNA was extracted using the QiaAmp DNA Mini Kit (catalog no. 51304; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), DNA quality was assessed using the 260:280 ratio measured with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer, and DNA was quantified with a Qubit fluorometer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Samples consisted of atrophic endometrium obtained from routine hysterectomy or pelvic resection for nonendometrial cancers in postmenopausal individuals. In addition, 42 endometrial tumor samples were obtained from the Cooperative Human Tissue Network. They included 20 endometrioid carcinomas (EECs), 11 serous tumors, and 11 clear cell tumors. Tissues were snap frozen after surgery and stored at −80°C. Genomic DNA was isolated using the Puregene Blood Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer's instructions. DNA quality and concentration were assessed using a SmartSpec Plus spectrophotometer (BioRad, Hercules, CA).

Lung, Stomach, Colon, and Breast Tumor Panels

We purchased 96-well plates that contained genomic DNA from tumor and normal samples for each tumor type from Amsbio (Cambridge, MA). Normal DNA was obtained from pathologically normal donors; samples were not isolated from normal adjacent tissues from donors with tumors. Amsbio extracted genomic DNA from a variety of frozen tissues using a modified guanidine thiocyanate technique and dissolved it in 1× TE buffer (10 mmol/L Tris, pH 8.0, 1 mmol/L EDTA). Each plate contained 40 tumor samples and eight normal tissue samples in technical duplicates. Each well contained 5 μL of genomic DNA at approximately 4 ng/μL, yielding 20 ± 3 ng of genomic DNA per sample (mean ± SD).

Methylation Analysis

Each dilution of genomic DNA was bisulfite converted with the EZ DNA Methylation-Direct Kit (catalog no. D5020 for a single sample or D5023 for the plate; Zymo Research, Irvine, GA), PCR amplified, and sequenced.

Human Methylation Array

Gynecologic samples were analyzed with the HumanMethylation27 Illumina BeadChip. The hybridization reaction was performed according to the manufacturer protocol, and samples were scanned using the Illumina iScan System.

Amplicon Generation

To generate a 302-bp PCR product from ZNF154, we used forward (5′-GGTTTTTATTTTAGGTTTGA-3′) and reverse (5′-AAATCTATAAAAACTACATTACCTAAAATACTCTA-3′) primers. The primers contained different adapters at their 5′ ends: forward adapter: 5′-ACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCT-3′, reverse adapter: 5′-GTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCT-3′. The primer design assumed all non-CpG Cs are converted with sodium bisulfite to Ts. The primers annealed to regions in the genomic DNA sequence devoid of any cytosines in a CpG context. PCR reactions contained 0.25 μL of 5-U/μL TaKaRa EpiTaq HS DNA Polymerase (for bisulfite-treated DNA) with 10× EpiTaq PCR Buffer, 5 μL of 25 mmol/L MgCl2, 6 μL of 2.5 mmol/L dNTP mix (catalog no. R110A; TaKaRa Bio Inc., Kusatsu, Japan), and 1 μL each primer at 12.5 μmol/L in 50-μL total volume. Cycling conditions were 95°C for 10 minutes, 45 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds, 48°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 60 seconds, and 72°C for a 7-minute final extension. PCR products were verified by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel.

After PCR, one or two rounds of product cleanup were performed by adding 37.5 μL of Agencourt Ampure XP PCR Purification Beads [catalog no. A63881; Beckman Coulter Genomics (formerly Agencourt), Danvers, MA] to the 50-μL PCR mixture. PCR products were verified by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel. Following cleanup, barcodes (Illumina Amplicon Indexing Oligos) were added in a second round of PCR, using 25 μL of 2× Phusion Master Mix (catalog no. M0531L; New England Biolabs Inc., Ipswich, MA) and 1 μL each bar-coded primer at 25 μmol/L in 50-μL total volume. Cycling conditions were 98°C for 30 seconds, 8 cycles of 98°C for 10 seconds, 65°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for a 5-minute final extension. A final round of XP PCR purification bead cleanup was applied, as before, to remove excess bar-coding oligonucleotides.

Amplicon Sequencing

PCR products were sequenced at the NIH Intramural Sequencing Center using the Illumina MiSeq platform with reagent kit version 3 (Illumina Inc.) to generate paired-end, 300-bp reads (200 bp for the lung plate). Briefly, agarose gel analysis was performed for each well in the 96-well amplicon plate. On the basis of the intensity of the product bands, the relative concentration of each sample was estimated. Using these values, a pool was created that adjusted for relative differences. The concentration of this pool was determined using the Illumina/Universal Library Quantification Kit (Kapa Biosystems Inc., Wilmington, MA). An aliquot of the pool was run on a MiSeq (Illumina Inc.) using a MiSeq Reagent Nano kit version 3. This quality control run consisted of 25 cycles followed by a 6-cycle index read, which provided an accurate profile of the representation of the samples in the pool. If necessary, an additional volume of poorly represented amplicons was added to the pool. The final pool was then sequenced on the MiSeq. Both MiSeq runs were spiked with a PhiX control library to improve base diversity. The PhiX library typically accounted for 30% to 50% of reads. Postrun processing of data were performed using RTA version 1.18.42 and CASAVA software version 1.8.2 (Illumina Inc.).

Presentation of Changes in Methylation

We report methylation levels in percentages or fractions (percentage per 100). Importantly, to avoid possible confusion, when we note a methylation difference of X%, we refer to an absolute difference of X units (0 to 100), not a relative X% change from the current methylation level. For example, if the reference methylation level is 30%, then a 10% difference from the reference level indicates 20% or 40% methylation, not 27% or 33%.

Alignment of Sequencing Data

We have observed that base quality deteriorates substantially in the second half of the paired-end sequence reads, especially the second reads. Therefore, because the reads were expected to overlap, we adjoined the first 200 bp from the first read to the first 102 bp from the second read (after reverse complementation) to produce single fragments of the expected 302-bp length.

We aligned the resulting full-length fragments to the human genome version GRCh37/hg19 using Bismark version 0.7.12.9 This procedure filtered out nonaligning reads and returned the number of aligned reads and methylation levels at each C, including each of the 20 CpGs in the amplicon and cytosines in non-CpG contexts, and mean methylation across each sample in CpG, CHG, and CHH contexts (where H represents A, C, or T). Non-CpG methylation was used as an internal upper-bound estimate of the inefficiency of bisulfite conversion because little appreciable cytosine methylation occurs outside CpG dinucleotides. Moreover, the alignment files contained the patterns of methylated bases within individual sequence reads.

The mapping efficiency (ie, the percentage of reads aligned to the genome out of total sequenced reads) varied from 0% to 89% (median, 18%) across sample replicates. Most, if not all, of the unaligned reads show clear primer dimer signatures, such as repeated forward and/or reverse primer and adaptor sequences, and typical poly-A artifactual base calls extending beyond the actual fragment size. These fragments were the most likely cause of the additional lower bands observed on our agarose gels; however, genomic alignment effectively filters them from the analysis.

The fraction of cytosine nonconversion in non-CpG contexts calculated by the Bismark application is, in fact, an underestimate because it takes into account the cytosines in the primer regions, which are expected to be always converted due to primer design (the primers hybridize only to Cs that are converted to uracil). To directly estimate nonconversion percentages in the aligned reads, we examined the Cs in a CHG and CHH context. The 302-bp ZNF154 amplicon contains 14 Cs in a CHG context (two within each of the primer regions and 10 between) and 59 Cs in a CHH context (six and four within the forward and reverse primers, respectively, and 49 between). Therefore, Bismark estimates were corrected by factors of 14/10 = 1.40 and 59/49 = 1.20 for CHG and CHH contexts, respectively. Indeed, when we directly analyzed nonconversion percentages in the aligned reads, excluding cytosines within primer regions, the slopes in linear regressions of our direct estimates versus Bismark estimates closely agreed with these factors: 1.35 and 1.22 for CHG and CHH contexts, respectively.

We use the nonconversion percentage in non-CpG context as an upper limit of the inefficiency of sodium bisulfite treatment. Assuming a similar effect at all cytosines, we can correct the reported CpG methylation levels. In this way, we calculate a true percentage of methylation CpG as mt = 100 (mo − e)/(100 − e), where mo is the observed percentage of mCpG, and e is the nonconversion percentage of unmethylated cytosines. Hence, the difference between the observed and true levels is mo − mt = (100 − mo) e/(100 − e).

Taking the maximum of the four estimates of non-CpG methylation/nonconversion for each sample as e (ie, two direct estimates for CHG and CHH contexts, as described above, and two estimates from Bismark), the median correction in percentage of mCpG, or the median of mo − mt, was 0.4, and the maximum was 2.8 (on a scale of 0 to 100). Given such a small effect, we kept the uncorrected values.

Sample Reproducibility

Comparison of sample duplicates in the four 96-well tumor plates revealed that duplicates with >1000 aligned reads closely agreed, in accord with recent reports.10 However, two outlier samples on the colon plate had duplicate methylation signals of 60% and 20% (with >1000 aligned reads in each duplicate), indicating that duplicates from the two samples had been inadvertently swapped. These samples were removed from the analysis. To maximize the number of samples retained for further analysis, we summed reads from both duplicates for each sample. A sample was retained if there were >1000 aligned reads in total unless the following two conditions occurred: each duplicate had >250 aligned reads, and mean CpG methylation differed by >0.2 (20%) between duplicates. The last condition excluded the two suspicious colon samples (but nothing else).

Analysis of Clinical Data

Most postalignment analysis was performed using the R language for statistical computing version 3.1.1 (http://www.r-project.org).11 We used analysis of variance (R functions lm and anova) to regress mean sample methylation on age, sex, and tumor diagnosis (subtype and differentiation level or grade). We used both a full and shortened version of diagnostic data; the shortened version excluded tumor differentiation levels (not available for stomach) and produced fewer categories, with larger sample sizes. We used single-term deletions in the model (R function drop1) to estimate the significance of these predictors; there were no interaction terms in the model.

Extraction of Sequencing Read Methylation Patterns

Most aligned reads (approximately 99.5%) had the expected starting coordinate (chr19:58220404); most of the rest aligned to neighboring bases, with several single-occurrence exceptions. Only reads with 20 CpGs (based on Bismark context calls) that were aligned to the expected starting coordinate were retained, yielding 93% to 98% (median, 96%) of the aligned reads reported by Bismark application. This finding is consistent with a Phred base quality score of approximately 30 (ie, a base call error rate of 0.001). The 20 CpGs translate to 40 bases that can be miscalled, which occur at rates of approximately 0.04, or 4%, of aligned reads. Comparing mean sample methylation between the values reported by Bismark and those based only on the reads we retained, the maximal absolute difference was negligible, 0.6% or 0.006 (the median absolute difference was only 0.13%).

Hierarchical Clustering of Samples Based on the Most Abundant Patterns

The 1000 most frequent methylation patterns in each sample were kept, with their union yielding 57,926 distinct patterns. The union of the 30 most abundant patterns in normal and 30 most abundant patterns in tumor samples yielded 45 distinct patterns that were used in hierarchical clustering. Selection of the most abundant patterns was based on ranking the means of the pattern fractions across tumor and normal tissue samples. On average, at least twice as many single-C read patterns were observed in normal samples than were expected from our estimates of inefficient sodium bisulfite conversion of fully unmethylated reads (P < 10−6, Wilcoxon signed-rank test), arguing that the single-C patterns are likely to be real events and not artifacts of incomplete conversion.

The fractions of these 45 patterns across 218 samples were log-transformed after replacing any fractions with a value of zero with values represented by one-tenth the minimal nonzero value for that pattern across all samples. To perform hierarchical clustering, we used the R functions heatmap.2 (package gplots) and hclust (package stats) with the ward.D2 agglomerative clustering method and Euclidean distance. Because the data were log-transformed, distance was based on fold changes in pattern fractions.

Calculation of Read Fractions with k Methylated CpGs

As stated previously, only sequence reads with 20 CpGs (based on Bismark context calls) that aligned to the starting coordinate chr19:58220404 were retained. In each sample, sequence reads with equal numbers of methylated CpGs (0 to 20; ie, values of k), were counted together in the read fractions (nk). The sum of all nk was normalized to 1. Using the set of nk, we defined the following ratios:

x = n20/(n0 + n20), (1)

(2)

and z = (n19 + n20)/(n0 + n19 + n20). (3)

Note that the mean mCpG fraction per sample can be calculated as follows:

. (4)

ROC Curve Classification

We used the R package pROC to calculate area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) CIs (using the default deLong method12). We used the R package ROCR for convex hull calculation.13, 14 The P value for the AUC was obtained from a Wilcoxon rank sum test evaluating the hypothesis that the distribution of the ranks in the two groups (normal tissue and tumor samples) is equal (if this hypothesis is correct, the AUC should be 0.5).

Dilution Simulations

We randomly matched one of the 34 normal samples, Nj, to each tumor, Ti, of the 184 tumor samples and mixed the two sample signals together at a chosen fraction, f, yielding an in silico diluted tumor value, Dij, where Dij = (1−f) × Ti + f × Nj.

Each Ti was randomly matched with one of the normal tissue samples 100 times, resulting in a set of 18,400 in silico tumor DNA dilutions. All Ti's and Nj's were represented as vectors containing normalized frequencies nk of aligned reads with given numbers of methylated CpGs (k between 0 and 20) and methylation levels at each of the 20 CpGs. The fraction, f, of normal signal in the mixture ranged from 0.1 to 0.99, with intermediate values of 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, 0.925, 0.95, and 0.975. In the ROC analysis, each dilution level (or f) was analyzed individually.

Machine Learning Classification

We applied k-nearest neighbors (KNN) and support vector machine (SVM) algorithms, using the three alternative sample representations: i) methylation values at each of the 20 individual CpGs, ii) the 45 most recurrent pattern frequencies, and iii) frequencies of groups of patterns nk with k methylated CpGs (0 ≤ k ≤ 20). For our computationally diluted data sets we used only the first and third representations.

Each representation was used as is or log-transformed. To avoid infinities due to log (0) in the latter case, we tried three alternative thresholds, e = {1e−5, 1e−3, 0.1}, and the data were transformed as log(data + e). To implement KNN algorithms, we used the knn.cv function from the R package class, with 1, 3, 5, 7, or 9 nearest neighbors; even numbers were omitted to avoid randomly resolved draws. To implement SVM, we used the svm function from R package e1071 and wrote a wrapper code to perform the leave-one-out cross-validation. We set the svm parameter class.weights as inversely proportional to the class sizes used in training, with the mean set to 1, and used five alternative cost values: 0.1, 1, 10, 100, or 1000. Other parameters were assigned the default values; for example, we used radial kernel.

Results

Regional Assessment of ZNF154 DNA Methylation

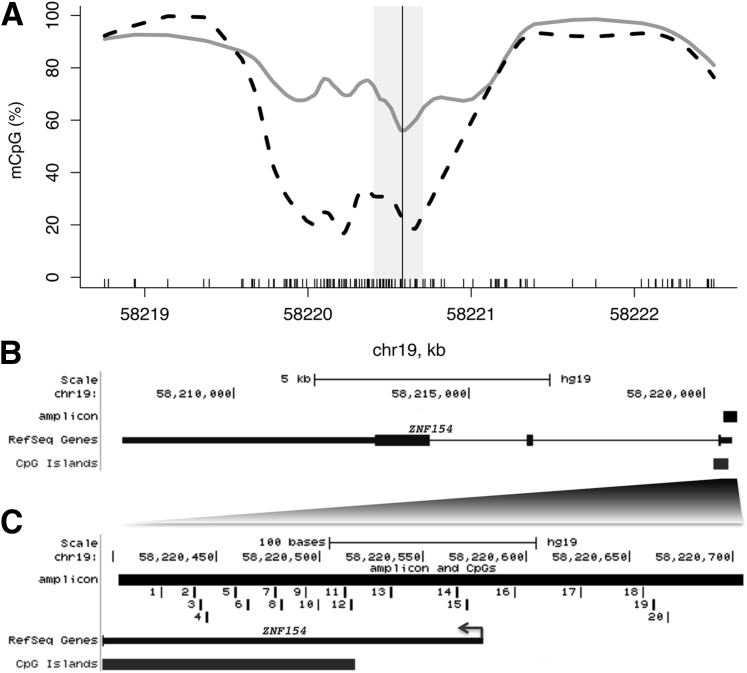

Our previous analysis of DNA methylation data in TCGA cohorts revealed that the ZNF154 transcription start site (TSS) is hypermethylated in 15 different solid epithelial tumor types compared with baseline methylation in normal tissue.8 Although all available probe sites from the Illumina 450 k Infinium methylation array were examined, the sparsity of probes across the ZNF154 locus prohibited analysis of the breadth of the hypermethylated region (HMR). We could only estimate that the HMR was between approximately 750 and 11,700 bp long. However, whole genome bisulfite sequencing data from matched tumor and normal colorectal tissue published in the Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo; accession number GSE46644) displayed a 1.5- to 2.0-kb region of tumor hypermethylation that centered around the ZNF154 TSS (Figure 1A), and other samples showed a similar HMR as well.15, 16 On the basis of these data, we designed a 302-bp PCR amplicon to cover a part of the ZNF154 HMR we identified,8 including the TSS and part of the associated CpG island (Figure 1, B and C). This 20-CpG amplicon is positioned centrally in the tumor-specific HMR, which should be optimal for distinguishing tumor from normal samples.

Figure 1.

DNA methylation profile around the transcription start site (TSS) of ZNF154. A and B: A smoothed CpG methylation (mCpG) profile in a colon tumor sample (gray line) and adjacent normal tissue (dashed black line), obtained from whole-genome bisulfite sequencing data (A). The rug plot illustrated along the bottom of the panel marks all CpG positions (A). The TSS (vertical line, A) and the amplicon interval (gray rectangle, A) correspond to the region of the UCSC Human Genome Browser (black rectangle, B). C: Genomic positions of 20 CpGs in the 302-bp ZNF154 amplicon: enlarged view of the TSS region and partial overlap with the annotated CpG island.

Validation of Bisulfite Amplicon Sequencing Reproducibility Using Cell Line DNA

The harsh conditions imposed by sodium bisulfite treatment cause fragmentation and damage to DNA molecules, suggesting that repeated sampling from very low quantities of DNA could give variable results when drawn from the same starting material. Therefore, we assessed the technical variability of our PCR amplification method by sampling amplifiable DNA molecules at very low amounts, simulating the amplification of low-copy-number tumor DNA fragments.17 For this purpose, we sampled genomic DNA at 20, 50, and 100 ng (in duplicate) from three replicate culture flasks of the tumor-derived cell line K562 and the non-tumor cell line GM12878. We treated each sample with bisulfite, generated PCR amplicons, added barcodes, and sequenced the products on the Illumina MiSeq platform. Sequence reads were aligned to a converted human genomic reference at the target locus (hg19, chr19:58220404–58220705) using the tool Bismark.9 For GM12878, 16 samples yielded aligned reads totaling 1276 to 120,500 reads per sample at the amplicon locus with a median of 23,460. For K562, 11 samples yielded aligned reads, with 1796 to 237,900 reads per sample and a median number of 26,480 (see Materials and Methods).

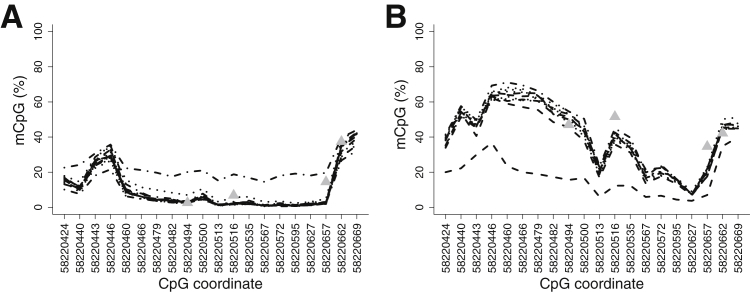

For both cell lines, MiSeq sequencing data across replicates from different starting DNA concentrations revealed robust methylation signals with minimal variation (Figure 2). The consensus profiles of methylation at each CpG emerged from overlap of 15 of the 16 GM12878 replicates and 10 of the 11 K562 replicates. Notably, for each cell line, one replicate fell out of the consensus profile. Excluding these outlier samples, the mean percentage of mCpG for K562 cells was 40.7% compared with 10.1% for GM12878. The SD of the percentage of mCpG at each of the 20 CpG dinucleotides was small, ranging from 0.5% to 3.4% for GM12878 and 0.6% to 3.8% for K562. Moreover, the methylation trends were similar to those observed in the Illumina array methylation data generated by the ENCODE Consortium for K562 and GM12878 at four probes in the same region (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Reproducibility data of amplicon sequencing products from bisulfite-converted cell line DNA. Results are shown for GM12878 (A) and K562 (B) cell lines. Each line represents a different replicate. Gray triangles represent the percentage of CpG methylation (mCpG) at four CpG positions present on the Illumina methylation array data, generated from the same cell types by ENCODE.

Thus, methylation at ZNF154 discriminates a tumor-derived cell line, K562, from a nontumor cell line, GM12878, derived from the transformation of phenotypically normal human lymphoblasts (P = 2 × 10−5, Wilcoxon rank sum test, including the outliers). Using as little as 20 ng of genomic DNA, bisulfite amplicon sequencing produced reproducible data with minimal deviation (approximately 2%) in methylation signal between technical replicates. Importantly, we conclude that the use of technical replicates helps to filter unreliable measurements.

Bisulfite Amplicon Sequencing in Solid Tumor Gynecologic Samples

Next, we expanded our use of bisulfite amplicon sequencing to investigate methylation levels at the ZNF154 locus in genomic DNA extracted from eight normal endometrial samples and 42 endometrial tumors, comprising a collection of 20 EEC, 11 serous tumors, and 11 clear cell tumors.

A single technical replicate of each tumor sample was assessed, and samples with at least 1000 aligned reads were considered (excluding only one low-grade EEC sample with 402 aligned reads). By averaging the signal across the amplicon, we found that tumors had a 66% increase in median methylation levels relative to normal tissue (P = 2 × 10−5, Wilcoxon rank sum test) (Figure 3A). All tumor stages were hypermethylated relative to normal tissue (P ≤ 0.01, t-test). Stage IV tumors (one serous and one clear cell sample) were hypermethylated relative to each of the lower stages (P ≤ 0.05, t-test) (Supplemental Figure S1); however, no significant methylation differences were observed among endometrioid, serous, and clear cell tumor subtypes at this locus.

Figure 3.

Comparison of CpG methylation (mCpG) levels in tumor and normal endometrial samples, as determined by amplicon sequencing. A: Box plots of percentage of mCpG at each CpG position within the amplicon in normal (empty black) and tumor (shaded gray) samples. Samples contained a minimum of 1000 aligned reads. B: Scatterplot of tumor (T) methylation levels measured with Illumina methylation arrays at probe cg21790626 (x axis) versus amplicon sequencing at the corresponding genomic position, chr19:58220494 (y axis), in the same samples. C: Scatterplot of the mean percentage of methylation across all amplicon CpG positions for each normal (N) sample, plotted against duplicate values.

We compared Illumina methylation array data to bisulfite sequencing data generated from these same samples and found that the two array probes overlapping the amplicon produced consistent results with the bisulfite sequence data (Pearson correlation coefficients of 0.96 and 0.97 and mean differences of 5.7% and 3.9%) (Figure 3B and Supplemental Figure S2). The agreement between the sequencing and array methylation values was strongest at very high methylation levels (>80% mCpG) and more variable at lower methylation levels (<40% mCpG). One advantage of amplicon sequencing is the ability to assess bisulfite conversion of unmethylated cytosines within the amplicon, where incomplete conversion creates a false-positive signal for methylation. We examined all Cs in non-CpG contexts in our endometrial samples and found minimal nonconversion (between 0.3% and 6.4% unconverted Cs at non-CpG positions, with a median of 2.6%).

We observed several additional characteristics in the sequencing data. For example, a slight decrease in median methylation occurred in tumors across four CpGs that surround the TSS (chr19:58220579) (Figure 3A), suggesting that this area is more resistant to DNA methylation than surrounding regions. In addition, the variability in percentage of methylation across samples was greater at each CpG position in tumors than in normal tissue. The low variance in normal samples was expected because of their lowered heterogeneity compared with tumor samples. Finally, some tumor samples had lower methylation levels than some normal tissue samples (Figure 3A), with low percentage of mCpG, which is consistent with reports from TCGA that some tumors lack DNA hypermethylation profiles.18 However, all tumor samples had mean methylation levels higher than the median level of the normal samples. Taken together, these data confirm that methylation levels at the ZNF154 amplicon separate most uterine tumor samples from normal samples.

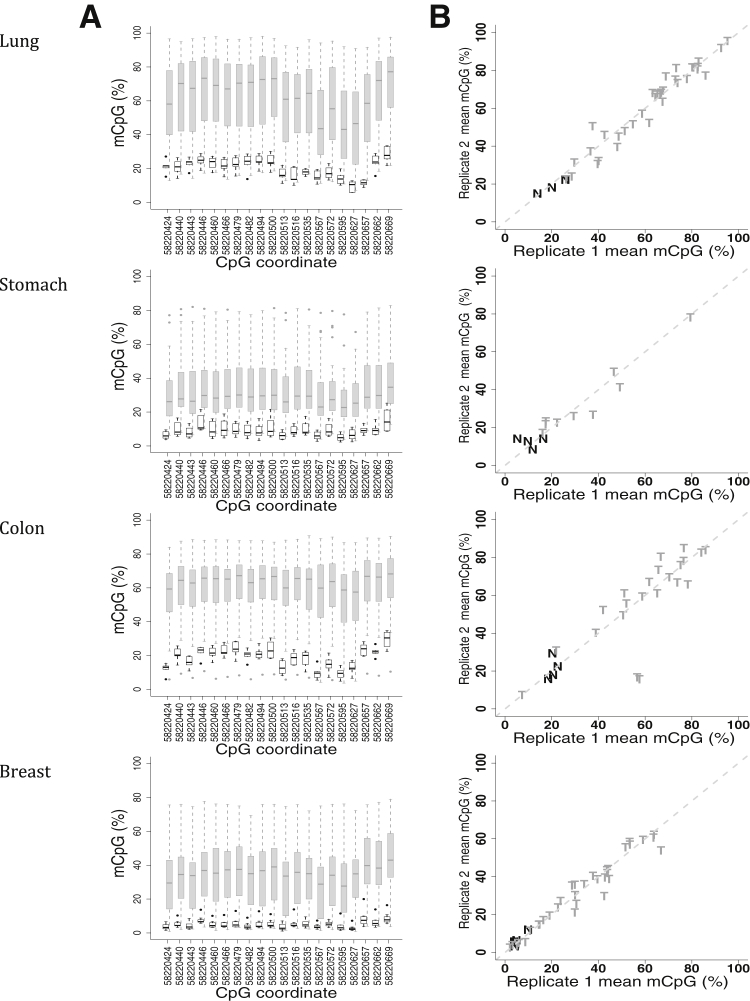

Methylation Measurements in Lung, Stomach, Colon, and Breast Tumors and Normal Tissues

Next, we assessed DNA methylation in lung, stomach, colon, and breast tumor panels, each with 40 tumor and eight normal tissue samples. All samples were examined in duplicate to estimate measurement accuracy. As with our analysis of endometrial cancer, we used samples that had >1000 aligned sequenced reads, resulting in informative sample sizes of 46 for lung cancer (40 tumor and six normal tissue samples), 40 for stomach cancer (34 tumor and six normal tissue samples), 36 for colon cancer (30 tumor and six normal tissue samples), and 47 for breast cancer (39 tumor and eight normal tissue samples).

In each of these data sets, the mean methylation within the amplicon region was greater in tumors than in normal tissue. The median percentage of mCpG in normal samples was 20%, 8%, 19%, and 4% for lung, stomach, colon, and breast tissue, respectively. In comparison, stomach and breast tumors had 20% and 31% increases in median methylation relative to corresponding normal tissue (P = 3.0 × 10−4 and P = 2.1 × 10−4, respectively; Wilcoxon rank sum test) (Figure 4A). Colon and lung tissue had greater increases of 44% and 45%, respectively (P = 3.9 × 10−4 and P = 4.1 × 10−6, respectively; Wilcoxon rank-sum test). Thus, the four tumor types were consistently hypermethylated at this locus compared with normal samples. The large magnitude of this hypermethylation bodes well for a strong discriminant in each tissue type. Methylation measurements between duplicates with >1000 aligned reads were consistent (Figure 4B), and the replicate data strongly correlated (Pearson correlation coefficients, ≥0.966).

Figure 4.

Distribution of individual CpG methylation (mCpG) levels in lung, stomach, colon, and breast tumor and normal tissue samples. A: Box plots of the mean percentage of methylation, determined from bisulfite sequencing, at each CpG position within the amplicon in normal (empty black) and tumor (shaded gray) samples. Samples contained ≥1000 aligned reads. B: Scatterplots of the mean percentage of methylation across all amplicon CpG positions for tumor (T) and normal (N) samples are plotted against duplicate values, when both duplicates have at least 1000 aligned reads.

The characteristics associated with these tumor data were consistent with our previous findings. For example, the median methylation around the ZNF154 TSS (chr19:58220579) revealed a decrease with higher methylation levels at the CpG sites to the left and to the right. Variance was also greater in tumor samples than normal tissue samples. Moreover, the four tumor types included a subset of samples with methylation levels comparable to or below that observed for normal tissue samples. One tumor sample in each of the lung, stomach, and colon collections and three in the breast collection had mean methylation levels below the median of their respective normal tissues. This finding is consistent with TCGA reports of tumor samples that do not reveal aberrant DNA methylation.8, 18 We also performed quality control assessment of the samples and concluded that nonconversion rates of cytosines to thymines in all non-CpG contexts were extremely low, indicating that the false methylation rate was low (between 0.2% and 1.2%, all medians ≤0.6%).

Each tumor panel in our analysis provided information on tumor subtype and relative grade (differentiation level), as well as patient age and sex. Using linear regression, we assessed whether mean methylation was predicted by subtype (with or without grade), age, or sex. All tumor types were hypermethylated compared with normal tissue samples (P < 0.05) (Supplemental Figure S3). However, no statistically significant differences appeared between tumor subtypes, after correcting for age and sex. Sex was associated with methylation levels in stomach and colon tumors (where males tended to have lower and higher methylation, respectively, than females) (Supplemental Figure S4), with marginally significant P values (0.055 for stomach and 0.051/0.016 for colon, using subtype and grade/subtype). Despite the small sample sizes for subtypes and stages, we found some differences when comparing median methylation levels. For example, in lung, small cell carcinomas, and squamous cell carcinomas seemed to have 15% greater median methylation than adenocarcinomas and bronchioalveolar carcinomas (although not reaching statistical significance at P = 0.23, t-test). Moreover, we found 25% greater median methylation in colon and lung adenocarcinomas relative to stomach adenocarcinomas (P < 0.02, t-test).

Adenocarcinomas represented a large proportion of the subtypes in the endometrial (41/41), lung (11/40), stomach (31/34), colon (30/30), and breast (39/39) tumors. This is not surprising because adenocarcinoma is the most commonly diagnosed tumor subtype for each of these tissues.19, 20, 21, 22 When analyzing only adenocarcinomas, tumors had a mean of 30% hypermethylation in the lung and colon tumors relative to normal tissue and >20% in breast and stomach tumors relative to normal. In lung tissue, squamous cell and small cell carcinomas are associated with a history of tobacco use23 and are considered aggressive tumors; they found even higher median methylation levels in our data set. Breast tumors in our study were predominantly represented by invasive ductal carcinomas (33/39), which have a median methylation level of 34% compared with just 4% in normal breast tissue.

Classification of Tumor and Normal Samples Using Methylation Patterns

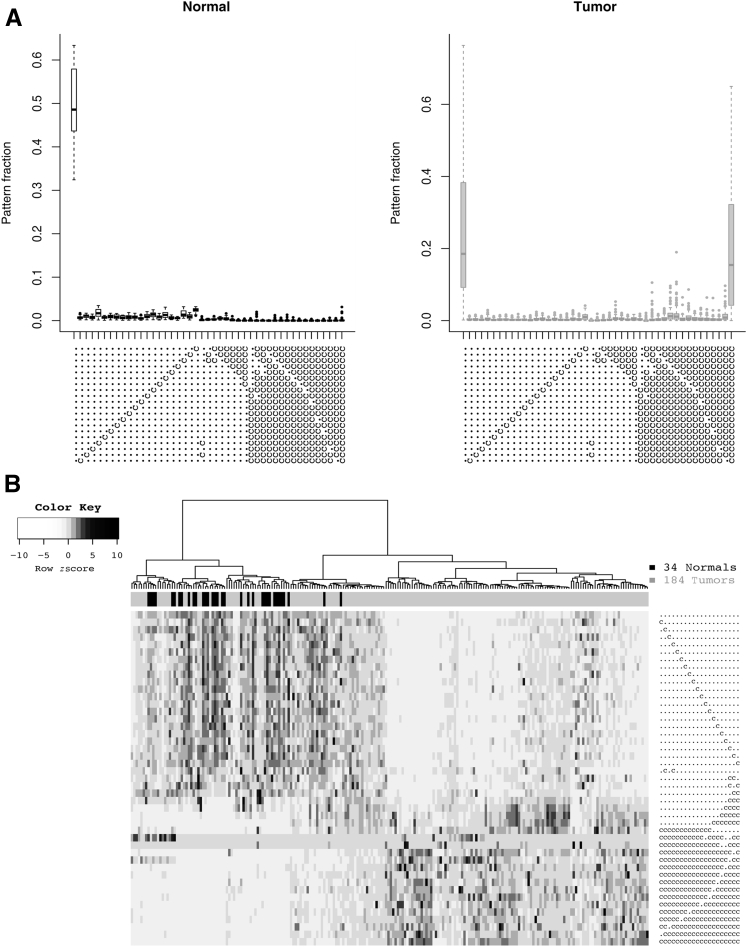

To evaluate the ZNF154 CpG island (CGI) as a pan-cancer marker for detecting tumors, we pooled the data from endometrial, colon, stomach, lung, and breast tissue samples, giving a total of 34 normal and 184 tumor samples. We examined patterns of methylation and compared their frequencies between tumor and normal samples. Next, we assessed the performance of various approaches for classifying samples as either tumor or normal based on these pattern frequencies.

We began by recording the position of each methylated CpG in each aligned read for every sample. The 20 CpG positions in our amplicon provided 220 or >1,000,000 possible methylation patterns. Each pattern was represented as a string of 20 characters encoding the methylation state of each CpG in the amplicon as either methylated or unmethylated. We identified the 30 most frequent patterns across normal samples and the 30 most frequent patterns across tumors. Counting the 15 patterns common to both groups, the union yielded 45 distinct patterns. These patterns fell into two main categories: those with 0 or 1 methylated CpGs and those with high numbers of methylated CpGs (18, 19, or 20). The low-methylation reads were frequent in both normal and tumor samples, whereas the high-methylation reads were primarily present in tumors (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Methylation patterns of aligned reads in tumor versus normal endometrial, colon, stomach, lung, and breast tissue samples. A: Frequency of the 45 most repeated patterns. Unmethylated cytosines converted to thymines appear as (.), whereas methylated cytosines that were protected from conversion appear as (c). Each symbol represents the status of one of the 20 CpG cytosines in the amplicon. B: Hierarchical clustering of the samples based on these 45 patterns. Heat map coloring reflects the relative abundance of a given pattern across samples—going from white to black in each row or pattern would correspond to moving from the bottom upward in the merged tumor-and-normal box plot for that same pattern, similar to A.

Initially, each sample was categorized as a tumor or normal sample using this set of 45 patterns. In unsupervised hierarchical clustering of samples (Figure 5B), we designated the left topmost branch as negative or normal sample classification and the right branch as positive or tumor sample classification. The true-positive rate of classification was 81%, with a false-positive rate of 6%.

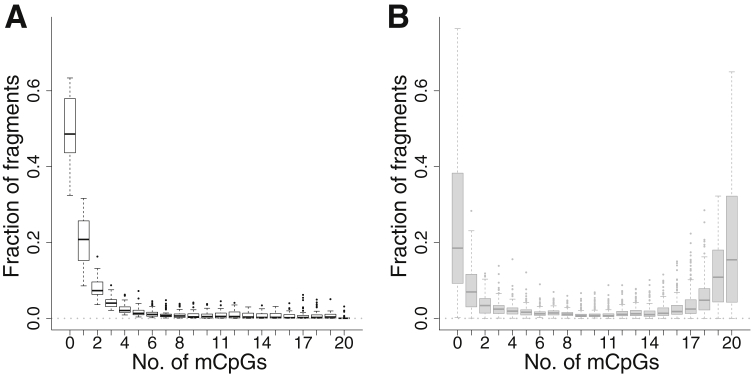

Alternatively, we binned all possible methylation patterns by the total number of methylated CpGs per read. With exactly 0 to 20 methylated CpGs, each aligned read was placed into one of 21 possible groups. We then used the normalized frequencies of aligned reads in these groups to classify tumors. Their distribution across normal and tumor samples is shown in Figure 6. In normal samples, approximately half of aligned reads were not methylated (Figure 6A), and most of the remaining reads contained <10 methylated CpGs. However, there was a tiny fraction of completely methylated reads (median, 0.04% of reads). In tumors (Figure 6B), completely unmethylated reads were less common, at 19%, and completely methylated reads were much more common than in normal samples, at 15%. All 184 tumors had completely methylated reads. Unfortunately, the presence of completely methylated reads in at least a subset of normal samples prevented classifying tumors simply based on the presence of these reads.

Figure 6.

Levels of CpG methylation (mCpG) of aligned reads in tumor versus normal endometrial, colon, stomach, lung, and breast tissue samples. Frequency of aligned reads as a function of the number of mCpGs, from 0 to 20, in normal (A) and tumor (B) samples. Different patterns with identical numbers of mCpGs have been grouped together.

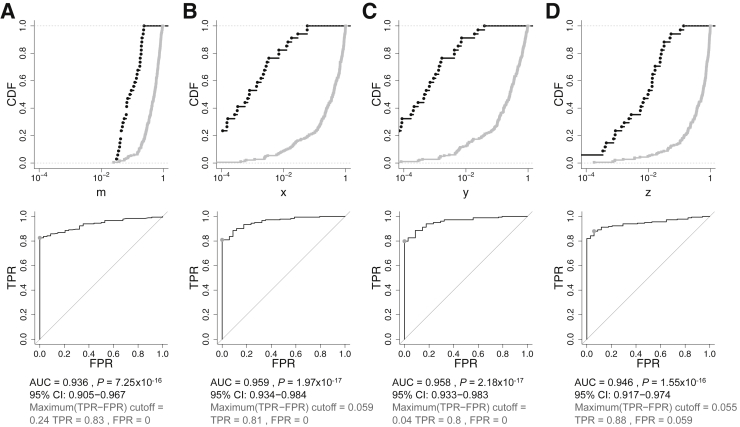

Finally, the frequency of all or a subset of these methylation pattern groups was used to classify each sample. We created ratios defined by subsets of these methylation pattern groups to assess the optimal classification approach (see Materials and Methods). We compared the classification performance of these ratios with that of the mean methylation fraction per sample, m (Figure 7A), using ROC curve analysis. This analysis allows one to choose any desired specificity and sensitivity represented along the curve. The two groups of patterns that differed the most were fully unmethylated and fully methylated reads. Focusing on just these two groups, we defined a ratio, x, to distinguish tumor from normal tissue samples (Figure 7B). In the absence of partially methylated reads, x would represent the mean methylation fraction per sample, becoming identical to m. We also combined fully unmethylated reads with reads with low methylation (five or fewer mCpGs) to define the ratio, y (Figure 7C). Similarly, we combined fully methylated reads with reads with near complete methylation (at 19 CpGs) to define the ratio, z (Figure 7D). The three ratios, x, y, and z, performed similarly, with AUCs between 0.946 and 0.959. This represents marginal improvement over the AUC value of 0.936 obtained using m and indicates that the strongly discriminating signals detected in tumor tissue can be classified using the mean methylation level. Nevertheless, the same simplicity may not apply to samples generated from circulating tumor DNA where the tumor signal is likely to be diluted in a background of nontumor signal.

Figure 7.

Distinguishing tumor samples from normal tissue based on DNA methylation in endometrial, colon, stomach, lung, and breast samples. Cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) (top panel) and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves (bottom panel) are shown. CDFs of normal and tumor samples are in black and gray, respectively, plotted against a logarithmic x axis. ROC curves reveal the point of the maximal sum of sensitivity and specificity (gray dot). Each column contains CDFs and ROC curves corresponding to a different sample measurement, scaled to vary between 0 and 1. A: Mean fraction (percentage per 100) of methylated CpGs per sample, m. B–D: The results for the x, y, and z ratios, respectively, defined in the text. FPR, false-positive rate (ie, 1 − specificity); TPR, true-positive rate (ie, sensitivity).

Simulation: Detection and Classification of Dilute Tumor DNA in Blood

Given our robust detection of hypermethylation in solid tumor surgical resections from different cancer types, we investigated the clinical relevance of the ZNF154 CGI locus as a pan-cancer marker in a blood-based screening. We constructed a collection of in silico data designed to simulate dilution experiments using the data set generated from 34 normal tissue and 184 tumor tissue samples from panels comprising five tumor types. Briefly, each dilution sample was generated by randomly and repeatedly matching each tumor sample to a normal tissue sample, independent of sample origins, and mixing their data together in a defined ratio. We varied the fraction of normal signal in the mixture from 0.1 (10%) to 0.99 (99%), balancing the tumor contribution from 90% to 1% of the input methylation signal. Each dilution level gave rise to a separate data set. We assumed that the low methylation signal observed in our 34 normal tissue samples was a suitable approximation of methylation that we may observe in normal blood, in agreement with data from methylation array studies (eg, Gene Expression Omnibus; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo; data sets GSE64950 with 36 samples from six individuals and GSE55763 with 2711 samples from 2664 individuals).24 For example, the mean ± SD methylation of the four CpGs within the amplicon that are also represented on the methylation arrays (Figure 2) was 12% ± 7% in our normal tissue samples, comparable to the BMIQ-normalized25 measurements of 10% ± 5% and 6% ± 3% in the GSE55763 and GSE64950 data sets, respectively.

For each set of tumor dilutions, we performed the same classification analysis as was performed for the original tumor to normal comparison (Figure 7). The x and y ratios yielded the highest AUC values for all dilution levels, from 0 (undiluted) to 99% (Figure 8). As shown in Figure 7, the AUC for mean methylation, m, classification was just slightly below that for other predictors when considering undiluted samples. However, it deteriorated much faster than the others with higher dilution levels. The y ratio, which incorporates aligned reads with one to five methylated CpGs, performed slightly but consistently better than x, which is based solely on fully methylated and fully unmethylated reads. In addition to x, y, and z, we also considered a classification based on the fraction of fully methylated read outs of all reads. This measure performed similar to z at low dilutions, similar to x at intermediate dilutions, and similar to y at higher dilutions (not shown).

Figure 8.

Performance of the four selected predictors (m, x, y, and z; defined in text) in distinguishing endometrial, colon, stomach, lung, and breast tumors from normal samples at different simulated dilution levels. Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) is plotted as a function of simulated tumor DNA dilution. The leftmost AUC values (when fraction of normal DNA is 0) correspond to the data presented in Figure 7.

At the dilution using 90% normal data, the ratios x and y performed well, with AUCs of approximately 0.89, whereas the AUC for the m-based ROC was much worse, at 0.68. Even at the highest dilution considered, 99%, the x and y ratios had substantial ability to discriminate between tumor and normal samples, with AUCs of approximately 0.74 (P < 3 × 10−6, Wilcoxon rank sum test; 95% CI, 0.63–0.85) (Figure 9, B and C). At this dilution, the AUC for the m-based ROC was only 0.54, near the value of random guessing of 0.5 (P = 0.42; 95% CI, 0.43–0.64) (Figure 9A).

Figure 9.

Simulation: distinguishing endometrial, colon, stomach, lung, and breast tumors from normal samples when tumor signal is diluted. The graphs are arranged as in Figure 7. Tumor signal characteristics (gray CDFs) were simulated by mixing 1% tumor signal with 99% randomly picked normal signal. Normal samples are the same as in Figure 7 (black CDFs). A: Diluted tumors were practically indistinguishable from normal samples when relying on m, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.54. B–D: By contrast, the capacity for classification persisted over dilutions for the other signal measures, x, y, and z (AUCs of 0.73, 0.75, and 0.63, from left to right). As an example of the use of the convex hull (gray off-diagonal line), C shows an increase in the AUC from 0.75 to 0.79. CDF, cumulative distribution function; FPR, false-positive rate (ie, 1 − specificity); TPR, true-positive rate (ie, sensitivity).

Finally, to estimate the classification capacity of our approach for individual tumor types, we performed dilution simulations similar to those described above but with only one tumor type present at a time. We used the same, pooled set of normal tissue samples in each case, as an approximation of normal blood and to maximize the selection (Supplemental Figure S5). Endometrial and colon tumors were the easiest to classify, with the best AUCs, >0.95, up to 90% dilution. Breast tumors were the hardest to classify, with all AUCs at <0.90. In lung tumors, the AUC based on m (mean methylation) performed better than the alternatives (x, y, and z) at up to 70% dilution, but it quickly degraded at higher dilutions. We note that the results of our analysis that pooled tumors of all types together (Figure 8) reflected the relative numbers of samples of each type.

By modeling the data anticipated from blood samples, in which the amplification of target ctDNA will be mixed with target DNA from normal cells, we have explored whether our methods have potential for clinical diagnostics. Even when tumors contributed just 1% to the total methylation signal, we could discriminate tumors from normal tissue samples using specific methylation patterns at the ZNF154 CGI, with an AUC of 0.74 (Figure 9, B and C). A mathematical technique, constructing a convex hull, can improve the ROC curve and increase the AUC13, 14; this somewhat improved our classification performance to the AUC of 0.79 (Figure 9C and Supplemental Figure S5).

Tumor Classification Using Machine Learning

In addition to the straightforward classification schemes described above, we investigated how well we could distinguish tumors from normal tissue using KNN and SVM algorithms. When we considered the solid tumor data (Supplemental Figure S6), the performance of SVM using the most abundant pattern frequencies was somewhat better than hierarchical clustering performance (Figure 5B) using the same data (ie, frequencies of the 45 most recurrent patterns). Overall, however, KNN and SVM classification performance was similar across the three alternative representations (Supplemental Figure S6) and, moreover, similar to the performance based on scalar predictors m, x, y, and z defined in the main text (Figure 7). We also applied SVM and KNN cross-validation to our computationally diluted data sets but found no performance gain. For example, at 90% dilution, SVM and KNN performance was at best comparable to that of x- or y-based classification, whereas at 99% dilution the SVM and KNN predictions were often worse than a random guess (true-positive rate less than false-positive rate) or had severe underfitting26 (Supplemental Figure S7).

Thus, we conclude that machine learning classifiers provide no additional benefit over approaches using simple methylation ratios with respect to the classification of tumor versus normal tissue using methylation around the ZNF154 CGI. The advantage of the scalar predictors m, x, y, and z is that they are easy to interpret and work with, which cannot be said about the machine learning algorithms, which require much more validation and parameter selection.

Discussion

We used deep bisulfite sequencing to examine recurrent hypermethylation around the ZNF154 TSS in five solid tumor types: lung, stomach, colon, breast, and endometrium. We confirmed that the ZNF154 amplicon region was significantly hypermethylated in these tumor types relative to normal samples. Furthermore, this hypermethylation occurred in most tumors examined, regardless of subtype, stage of differentiation, age, or sex. The discrimination between all tumor subtypes and normal controls was most prominent in endometrial, colon, and lung tissues (Supplemental Figures S1 and S3). We did not have adequate sample sizes to thoroughly investigate all subtype differences, except, perhaps, for endometrial tumors, in which we have not observed differential methylation among different subtypes. Therefore, further experimental testing with greater sample sizes and different tumor types may reveal associations between ZNF154 methylation and tumor subtypes, novel epitypes, disease pathology, or targeted therapies.

Given the reproducibility of hypermethylation across a breadth of solid tumor types and the sensitivity detected in our simulated dilutions, we predict that the ZNF154 amplicon can distinguish ctDNA in a blood-based test. Although published studies have detected and assessed the fraction of ctDNA based on mutations,27, 28, 29 mutation detection requires specific knowledge about the patient's mutation, and at this time it is not always clear what levels of ctDNA should be considered abnormal or warrant intervention.3, 30, 31, 32 Furthermore, it is difficult to implement mutation testing in ctDNA as a generalized diagnostic test for cancer because the mutations are so varied. Presence of ctDNA has also been detected and quantified using DNA hypermethylation.33 Consistent with this idea, we found that elevated methylation levels at ZNF154 appear to be prevalent across different tumor types providing application as a generalized test while potentially complementing ctDNA mutation testing applied to specific cancer types.

Estimates of ctDNA amounts in blood vary widely, ranging from fractions of a percent to most sample DNA.3, 27, 28, 29, 30, 33 Our computational simulation provides insight into how ZNF154 methylation analysis could be applied to blood samples. At a simulated 90% dilution, in which the tumor contributes only 10% of DNA signal, classification performance was good, with AUCs of 0.89 (Figure 8) (x and y ratios). Even a simulated 99% dilution yielded an AUC of 0.79. Because different tumor types have different hypermethylation levels and profiles, both relative to their normal tissue controls (Figures 3 and 4) and to the pooled normal tissues, we observed the best performance of the potential ZNF154 biomarker for the endometrial and colon tumors (Supplemental Figure S5). Overall, our in silico dilution estimates suggest that hypermethylation of the ZNF154 CGI region should be robustly detected as long as the ctDNA fraction is at or above single-digit percentage levels. Such sensitivity should be adequate to detect advanced cancer and some intermediate and early tumors, depending on the tumor type.30 We note that our solid tumor DNA samples may themselves be a mixture of tumor and normal cells, introducing an inherent dilution to the tumor methylation signal and making our estimates overly conservative.

We considered our methylation detection relative to other detection techniques. Currently, the predominant method used in DNA methylation-based cancer diagnostics is methylation-specific PCR (MSP), including its quantitative variants (qMSP).7, 31, 32, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40 The qMSP approach assumes that all CpGs in the targeted locus are either fully methylated or unmethylated and aims to quantify these two patterns. By comparison, our classification approach based on the ratio x of fully methylated reads to the sum of fully methylated and fully unmethylated reads was among our best performers. When we included partially methylated reads, only a modest improvement occurred (Figure 8) (x is close to y), whereas including near-completely methylated reads together with fully methylated reads led to decreased performance (Figure 8) (compare z to x ratios). Of note, qMSP provides no way to avoid some amplification of incompletely methylated reads together with fully methylated reads. Moreover, an amplicon of 300 bp is atypically long for MSP. As a proxy, when we discarded the five rightmost CpGs in the amplicon and reanalyzed our data, the classification performance decreased (Supplemental Figure S8), indicating an advantage to using longer reads. The largest decrease in classification, compared with the analysis using all 20 CpGs, was observed at the highest dilution (99%), with a top AUC of just 0.64; however, the classification based on m (mean methylation) remained the worst. Therefore, given all the considerations above, MSP classification performance is likely to be lower than the method described here. Furthermore, recent work comparing different methods of DNA methylation measurement has found that sequencing reveals better precision than qMSP.41

In the case of actual (nondiluted) solid tumors, a simple classification based on mean mCpG (m) performed on par with the ratio-based classifiers (x, y, and z), whereas for diluted tumors the best classification performance was achieved using combinations of frequencies of methylation patterns of individual DNA fragments (using x or y). Classification based on mean mCpG does not require such detail, but it performs the worst (Figure 8). Because neither arrays nor standard pyrosequencing (or Sanger sequencing) generate the detailed data provided by bisulfite sequencing, they will not provide optimal analyses. Likewise, other groups using bisulfite amplicon sequencing did not quantify methylation patterns of individual reads. This appears problematic, given the random fragmentation of amplicons generated there.10

Evaluation of ZNF154 methylation as a biomarker for cancer will require direct measurement in body fluids using the method described here. Given that plasma cell-free DNA fragments average <300 bp, our amplicon size might need optimization.3 Another factor that may potentially improve tumor detection is having internal DNA standards to quantify the DNA concentration.40 This information could be used to quantify the number of fully methylated reads per unit volume of blood, which may serve as an additional discriminative tumor signature. Ultimately, assessment of early- versus late-stage samples will reveal the range of diagnostic potential provided by this locus. We note that our analyses use a comparison of tumor to unmatched normal tissue samples, which precludes assessment of elevated methylation levels in premalignant tissues. Detection of premalignant tissue might in fact be beneficial, although in the context of a blood test we might see a hypermethylation signal only if such DNA reaches the bloodstream. We also note that we have not assessed tumor heterogeneity, which could influence the median methylation levels we measure in different tumor types.

In summary, bisulfite amplicon sequencing potentially recovers all read patterns present in a sample, allowing a more detailed analysis of methylation. With the use of this approach, ZNF154 hypermethylation may represent a pan-cancer biomarker for solid tumors and could potentially be used to diagnose tumors through circulating tumor DNA. A natural extension would then be tracking the effectiveness of chemotherapy or tumor recurrence using blood samples.

Acknowledgments

We thank the NIH Intramural Sequencing Center and Richelle Legaspi for dedicated work in processing and sequencing our amplicon libraries.

Footnotes

Supported by the Intramural Program of the National Human Genome Research Institute, NIH, and NIH grant HG200323 (L.E.).

Disclosures: None declared.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoldx.2015.11.004.

Supplemental Data

Distribution of mean methylation levels in endometrial tumor and normal tissue samples, stratified by tumor subtype (left panel) or stage (right panel). The number of samples in each category is shown above the box plots.

Scatterplot of tumor (T) methylation levels measured with Illumina methylation arrays at probe cg08668790 (x axis) versus amplicon sequencing at the corresponding genomic position, chr19:58220662 (y axis).

Distribution of mean methylation levels in lung, stomach, colon, and breast tumor subtypes and in normal samples. The number of samples in each category is shown above the box plots.

Distribution of mean methylation levels in lung, stomach, and colon tumors as a function of sex (female or male). The number of samples in each category is shown above the box plots.

Performance of the four selected predictors (m, x, y, and z) in distinguishing endometrial, colon, stomach, lung, and breast tumors from normal tissues at different dilution levels. The top row shows raw areas under the receiver operating characteristic curves (AUCs), whereas the bottom row shows AUCs of the convex hulls (Figure 9). The left column shows all tumors pooled together, such that the top left plot is identical to Figure 8. The other columns show performance when considering endometrial, lung, stomach, colon, or breast tumors individually, from left to right. The same pooled set of normal samples is used in all plots. Interestingly, the breast tumor AUC values based on all four features (m, x, y, and z) increased with dilution until approximately 20%; this was unexpected but is possible likely because of a relatively high proportion of undiluted breast tumors with methylation signals below those of pooled normal tissue samples.

True-positive rates (TPRs) and false-positive rates (FPRs) using k-nearest neighbors (KNN) and support vector machine (SVM) leave-one-out cross-validations to classify endometrial, colon, stomach, lung, and breast tumors versus normal tissues. Different data transformations are indicated by different symbols. Identical symbols on the same plot indicate different choices of nearest neighbors for the KNN algorithm (green) and different cost values for the SVM algorithm (brown). A: Results using a vector of 20 methylation values across individual CpGs for each sample (Figures 3 and 4). B: Results using methylation pattern fractions for each sample and the values derived from hierarchical clustering (Figure 5). C: Results using frequency of aligned reads with different numbers of methylated CpGs, nk (Figure 6). B also displays the values derived from hierarchical clustering (black square; cf. Figure 5B).

True-positive rates (TPR) and false-positive rates (FPR) using k-nearest neighbors (KNN) and support vector machine (SVM) leave-one-out cross-validations to classify endometrial, colon, stomach, lung, and breast tumors versus normal tissue. Different data transformations are indicated by different symbols. Identical symbols on the same plot indicate different choices of nearest neighbors for the KNN algorithm (green) and different cost values for the SVM algorithm (brown). Shown are typical results for tumor dilutions with 90% normal DNA signals (A) and 99% normal DNA signals (B), using frequencies of aligned reads with different numbers of methylated CpGs. The cases of apparently perfect or near-perfect SVM classification are actually an artifact of a misleading behavior that occurs with a low value of the cost parameter (0.1); in those leave-one-out cross-validations, when a normal sample is left out, there are 33 normal samples and 184 tumor samples in the training set, and the prediction for any test is always normal. When a tumor sample is left out, there are 34 normal samples and 183 tumor samples in the training set, and the prediction is always tumor. We have also validated this behavior with randomly generated 21-dimensional sample vectors drawn from a uniform distribution. This situation is similar to asymptotic SVM behaviors described in the literature.26

Analysis using only the 15 leftmost CpGs of the 20 in the ZNF154 amplicon. Frequencies of aligned reads, nk, with different numbers of methylated CpGs, k, from 0 to 15, in normal tissue (A) and tumors (B). C: Performance of the four selected predictors, m, x, y, and z, in tumor versus normal tissue classification. The performance of the x, y, and z–based classifications decreased substantially at greater dilutions (ie, greater fractions of normal DNA) compared with using all 20 CpGs (Figure 8). The mean methylation CpG (mCpG) fraction–based classification did not change appreciably when compared with the analysis using all 20 CpGs but remained the worst performer among the four predictors. Note that nk here and in the main text are not the same because truncated patterns group differently.

References

- 1.Siegel R., Ma J., Zou Z., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edwards B.K., Noone A.M., Mariotto A.B., Simard E.P., Boscoe F.P., Henley S.J., Jemal A., Cho H., Anderson R.N., Kohler B.A., Eheman C.R., Ward E.M. Annual Report to the Nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2010, featuring prevalence of comorbidity and impact on survival among persons with lung, colorectal, breast, or prostate cancer. Cancer. 2014;120:1290–1314. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gold B., Cankovic M., Furtado L.V., Meier F., Gocke C.D. Do circulating tumor cells, exosomes, and circulating tumor nucleic acids have clinical utility? J Mol Diagn. 2015;17:209–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mikeska T., Craig J.M. DNA methylation biomarkers: cancer and beyond. Genes (Basel) 2014;5:821–864. doi: 10.3390/genes5030821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bettegowda C., Sausen M., Leary R.J., Kinde I., Wang Y., Agrawal N. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:224ra24. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kinde I., Bettegowda C., Wang Y., Wu J., Agrawal N., Shih I.-M., Kurman R., Dao F., Levine D.A., Giuntoli R., Roden R., Eshleman J.R., Carvalho J.P., Marie S.K.N., Papadopoulos N., Kinzler K.W., Vogelstein B., Diaz L.A. Evaluation of DNA from the Papanicolaou test to detect ovarian and endometrial cancers. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:167ra4. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mikeska T., Bock C., Do H., Dobrovic A. DNA methylation biomarkers in cancer: progress towards clinical implementation. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2012;12:473–487. doi: 10.1586/erm.12.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sánchez-Vega F., Gotea V., Petrykowska H.M., Margolin G., Krivak T.C., DeLoia J.A., Bell D.W., Elnitski L. Recurrent patterns of DNA methylation in the ZNF154, CASP8, and VHL promoters across a wide spectrum of human solid epithelial tumors and cancer cell lines. Epigenetics. 2013;8:1355–1372. doi: 10.4161/epi.26701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krueger F., Andrews S.R. Bismark: a flexible aligner and methylation caller for Bisulfite-Seq applications. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1571–1572. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masser D.R., Berg A.S., Freeman W.M. Focused, high accuracy 5-methylcytosine quantitation with base resolution by benchtop next-generation sequencing. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2013;6:33. doi: 10.1186/1756-8935-6-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.R Core Team . R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2015. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qin G., Hotilovac L. Comparison of non-parametric confidence intervals for the area under the ROC curve of a continuous-scale diagnostic test. Stat Methods Med Res. 2008;17:207–221. doi: 10.1177/0962280207087173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis J, Goadrich M: The relationship between Precision-Recall and ROC curves. Proc 23rd Int Conf Mach Learn - ICML '06 2006, 233–240

- 14.Fawcett T. An introduction to ROC analysis. Pattern Recognit Lett. 2006;27:861–874. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ziller M.J., Gu H., Müller F., Donaghey J., Tsai L.T.-Y., Kohlbacher O., De Jager P.L., Rosen E.D., Bennett D.A., Bernstein B.E., Gnirke A., Meissner A. Charting a dynamic DNA methylation landscape of the human genome. Nature. 2013;500:477–481. doi: 10.1038/nature12433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geisen S., Barturen G., Alganza Á.M., Hackenberg M., Oliver J.L. NGSmethDB: an updated genome resource for high quality, single-cytosine resolution methylomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D53–D59. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ehrich M., Zoll S., Sur S., van den Boom D. A new method for accurate assessment of DNA quality after bisulfite treatment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:e29. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weisenberger D.J. Characterizing DNA methylation alterations from the cancer genome atlas. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:17–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI69740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dicken B.J., Bigam D.L., Cass C., Mackey J.R., Joy A.A., Hamilton S.M. Gastric adenocarcinoma: review and considerations for future directions. Ann Surg. 2005;241:27–39. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000149300.28588.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saso S., Chatterjee J., Georgiou E., Ditri A.M., Smith J.R., Ghaem-Maghami S. Endometrial cancer. BMJ. 2011;343:d3954. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d3954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Couraud S., Zalcman G., Milleron B., Morin F., Souquet P.-J. Lung cancer in never smokers–a review. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:1299–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Howlader N., Noone A.M., Krapcho M., Garshell J., Miller D., Altekruse S.F., Kosary C.L., Yu M., Ruhl J., Tatalovich Z., Mariotto A., Lewis D.R., Chen H.S., Feuer E.J., Cronin K.A., editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2012. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cornfield J., Haenszel W., Hammond E.C., Lilienfeld A.M., Shimkin M.B., Wynder E.L. Smoking and lung cancer: recent evidence and a discussion of some questions. 1959. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:1175–1191. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lehne B., Drong A.W., Loh M., Zhang W., Scott W.R., Tan S.-T., Afzal U., Scott J., Jarvelin M.-R., Elliott P., McCarthy M.I., Kooner J.S., Chambers J.C. A coherent approach for analysis of the Illumina HumanMethylation450 BeadChip improves data quality and performance in epigenome-wide association studies. Genome Biol. 2015;16:37. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0600-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teschendorff A.E., Marabita F., Lechner M., Bartlett T., Tegner J., Gomez-Cabrero D., Beck S. A beta-mixture quantile normalization method for correcting probe design bias in Illumina Infinium 450 k DNA methylation data. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:189–196. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keerthi S.S., Lin C.-J. Asymptotic behaviors of support vector machines with Gaussian kernel. Neural Comput. 2003;15:1667–1689. doi: 10.1162/089976603321891855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diehl F., Li M., Dressman D., He Y., Shen D., Szabo S., Diaz L.A., Goodman S.N., David K.A., Juhl H., Kinzler K.W., Vogelstein B. Detection and quantification of mutations in the plasma of patients with colorectal tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16368–16373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507904102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diehl F., Schmidt K., Choti M.A., Romans K., Goodman S., Li M., Thornton K., Agrawal N., Sokoll L., Szabo S.A., Kinzler K.W., Vogelstein B., Diaz L.A. Circulating mutant DNA to assess tumor dynamics. Nat Med. 2008;14:985–990. doi: 10.1038/nm.1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newman A.M., Bratman S.V., To J., Wynne J.F., Eclov N.C.W., Modlin L.A., Liu C.L., Neal J.W., Wakelee H.A., Merritt R.E., Shrager J.B., Loo B.W., Alizadeh A.A., Diehn M. An ultrasensitive method for quantitating circulating tumor DNA with broad patient coverage. Nat Med. 2014;20:548–554. doi: 10.1038/nm.3519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crowley E., Di Nicolantonio F., Loupakis F., Bardelli A. Liquid biopsy: monitoring cancer-genetics in the blood. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10:472–484. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fleischhacker M., Schmidt B. Circulating nucleic acids (CNAs) and cancer–a survey. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1775:181–232. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delpu Y., Cordelier P., Cho W.C., Torrisani J. DNA methylation and cancer diagnosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:15029–15058. doi: 10.3390/ijms140715029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jahr S., Hentze H., Englisch S., Hardt D., Fackelmayer F.O., Hesch R.D., Knippers R. DNA fragments in the blood plasma of cancer patients: quantitations and evidence for their origin from apoptotic and necrotic cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1659–1665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herman J.G., Graff J.R., Myöhänen S., Nelkin B.D., Baylin S.B. Methylation-specific PCR: a novel PCR assay for methylation status of CpG islands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:9821–9826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shivapurkar N., Gazdar A.F. DNA methylation based biomarkers in non-invasive cancer screening. Curr Mol Med. 2010;10:123–132. doi: 10.2174/156652410790963303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwarzenbach H., Hoon D.S.B., Pantel K. Cell-free nucleic acids as biomarkers in cancer patients. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:426–437. doi: 10.1038/nrc3066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dong Y., Zhao H., Li H., Li X., Yang S. DNA methylation as an early diagnostic marker of cancer (Review) Biomed Rep. 2014;2:326–330. doi: 10.3892/br.2014.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jin H., Ma Y., Shen Q., Wang X. Circulating methylated DNA as biomarkers for cancer detection. Methylation - From DNA, RNA and Histones to Diseases and Treatment. In: Dricu A., editor. InTech; Rijeka, Croatia: 2012. pp. 137–152. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoque M.O., Begum S., Topaloglu O., Jeronimo C., Mambo E., Westra W.H., Califano J.A., Sidransky D. Quantitative detection of promoter hypermethylation of multiple genes in the tumor, urine, and serum DNA of patients with renal cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5511–5517. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fackler M.J., Lopez Bujanda Z., Umbricht C., Teo W.W., Cho S., Zhang Z., Visvanathan K., Jeter S., Argani P., Wang C., Lyman J.P., de Brot M., Ingle J.N., Boughey J., McGuire K., King T.A., Carey L.A., Cope L., Wolff A.C., Sukumar S. Novel methylated biomarkers and a robust assay to detect circulating tumor DNA in metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2160–2170. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Redshaw N., Huggett J.F., Taylor M.S., Foy C.A., Devonshire A.S. Quantification of epigenetic biomarkers: an evaluation of established and emerging methods for DNA methylation analysis. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:1174. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Distribution of mean methylation levels in endometrial tumor and normal tissue samples, stratified by tumor subtype (left panel) or stage (right panel). The number of samples in each category is shown above the box plots.

Scatterplot of tumor (T) methylation levels measured with Illumina methylation arrays at probe cg08668790 (x axis) versus amplicon sequencing at the corresponding genomic position, chr19:58220662 (y axis).

Distribution of mean methylation levels in lung, stomach, colon, and breast tumor subtypes and in normal samples. The number of samples in each category is shown above the box plots.

Distribution of mean methylation levels in lung, stomach, and colon tumors as a function of sex (female or male). The number of samples in each category is shown above the box plots.

Performance of the four selected predictors (m, x, y, and z) in distinguishing endometrial, colon, stomach, lung, and breast tumors from normal tissues at different dilution levels. The top row shows raw areas under the receiver operating characteristic curves (AUCs), whereas the bottom row shows AUCs of the convex hulls (Figure 9). The left column shows all tumors pooled together, such that the top left plot is identical to Figure 8. The other columns show performance when considering endometrial, lung, stomach, colon, or breast tumors individually, from left to right. The same pooled set of normal samples is used in all plots. Interestingly, the breast tumor AUC values based on all four features (m, x, y, and z) increased with dilution until approximately 20%; this was unexpected but is possible likely because of a relatively high proportion of undiluted breast tumors with methylation signals below those of pooled normal tissue samples.