Abstract

All serious liver injuries alter metabolism and initiate hepatic regeneration. Recent studies using partial hepatectomy (PH) and other experimental models of liver regeneration implicate the metabolic response to hepatic insufficiency as an important source of signals that promote regeneration. Based on these considerations, the analyses reported here were undertaken to assess the impact of interrupting the hypoglycemic response to PH on liver regeneration in mice. A regimen of parenteral dextrose infusion that delays PH-induced hypoglycemia for 14 hours after surgery was identified, and the hepatic regenerative response to PH was compared between dextrose-treated and control mice. The results showed that regenerative recovery of the liver was postponed in dextrose-infused mice (versus vehicle control) by an interval of time comparable to the delay in onset of PH-induced hypoglycemia. The regulation of specific liver regeneration–promoting signals, including hepatic induction of cyclin D1 and S-phase kinase-associated protein 2 expression and suppression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ and p27 expression, was also disrupted by dextrose infusion. These data support the hypothesis that alterations in metabolism that occur in response to hepatic insufficiency promote liver regeneration, and they define specific pro- and antiregenerative molecular targets whose regenerative regulation is postponed when PH-induced hypoglycemia is delayed.

Recovery from any serious injury to the liver depends on the intrinsic ability of this organ to regenerate.1 Thus, the signals that control liver regeneration have been subjected to extensive investigation with the hope that new mechanistic knowledge can be translated into improved clinical management of liver diseases in humans. Mouse two-thirds partial hepatectomy (PH) is the experimental paradigm most commonly used for studying liver regeneration. Analyses using PH have shown that partial liver resection induces a characteristic hepatocellular proliferative response that is precisely controlled by specific cytokines, growth and transcription factors, and intracellular signaling events.1 This process ultimately restores normal hepatic mass and function, after which hepatocytes return to their pre-regenerative state of proliferative inactivity.1 Nonetheless, the earliest events that initiate hepatic regeneration and later signals that terminate this process remain incompletely defined, and translation of mechanism-based, proregenerative interventions into new treatments for liver diseases has not yet been achieved.

In addition to initiating hepatic regeneration, severe liver injuries alter metabolism.2, 3, 4 For example, mice subjected to PH develop hypoglycemia, followed by systemic catabolism and humoral and hepatic accumulation of specific metabolites.5, 6, 7, 8 These stereotypical changes are detectable almost immediately after surgery and resolve with regenerative recovery of the normal liver/body mass ratio. Moreover, some experimental manipulations that suppress PH-induced alterations in metabolism impair liver regeneration,5, 6, 7 and other interventions that amplify elements of this metabolic response accelerate regeneration.3 Together, those observations implicate the metabolic response to hepatic insufficiency as an important source of proregenerative signals. However, the specific molecular mechanisms by which metabolism controls liver regeneration remain poorly understood. The studies reported here were undertaken to clarify the functional importance and mechanistic role of PH-induced changes in glycemia during normal mouse liver regeneration, using parenteral dextrose supplementation to delay the onset of such hypoglycemia.

Materials and Methods

Partial Hepatectomy

PH was performed on 2- to 3-month-old male C57BL6/J mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME). Animals were maintained on 12-hour dark/light cycles with ad libitum access to standard rodent chow and water before and after surgery. At the time of surgery, mice were sedated with inhaled isoflurane (Vedco Inc., St. Joseph, MO) via an anesthesia vaporizer and then subjected to midventral laparotomy with exposure, ligation, and resection of the left and median hepatic lobes, followed by closure of the peritoneal and skin wounds as described previously.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16

Parenteral Dextrose Infusion

At the time of PH, one end of a sterilized catheter prefilled with sterile 22.5% dextrose [45% sterile dextrose (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) diluted 1:1 with phosphate-buffered saline] or half-strength phosphate-buffered saline (diluted with sterile water instead of dextrose) as control was implanted into the peritoneal cavity and the other end tunneled s.c. through the skin in the back of the neck and attached to a peristaltic pump (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). Pilot studies were initially conducted to compare PH-induced changes in blood glucose between mice treated with glucose infusion rates (GIRs) from 20 to 35 μg of glucose per gram of body weight (μg/g) per minute and controls administered an equal volume of vehicle. Those studies showed that provision of a GIR of 25 μg/g per minute (160 mL/kg per day) beginning immediately after PH, and subsequent adjustment of the GIR every 2 hours (based on glucometric analyses of tail vein blood) up or down by 5 μg/g per minute between 20 and 35 μg/g per minute (in an effort to maintain blood glucose within the normal, strain-specific, nonfasting range of 198 ± 14 mg/dL; Mouse Phenome Database, http://phenome.jax.org/db/qp?rtn=views/measplot&brieflook=32301, last accessed October 19, 2015, MPD:32301) reproducibly delays the onset of PH-induced hypoglycemia for 14 hours after surgery. This regimen of parenteral dextrose supplementation and glucose monitoring was used in all subsequent analyses. No postoperative mortality was observed in 53 control mice; however, 2 of 75 dextrose-infused animals died (one on the day of surgery and the other on postoperative day 1). There were no differences in postoperative morbidity (eg, decreased activity, jaundice, extreme weight loss, or piloerection) between the dextrose-infused and control mice. Therefore, such morbidity (which affected a minority of animals) was interpreted as a technical complication of the model, and data from morbid animals were excluded from subsequent analyses. All other animals remained well-appearing throughout the experiment and were sacrificed at serial times after surgery for serum or plasma and tissue harvest as described previously.1, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 Blood glucose profiles were generated with the glucometric data obtained from all nonmorbid animals. For other analyses, serum, plasma, or tissue samples from three to eight animals at each time point and in each treatment group were studied.

All experiments were approved by the Washington University Animal Studies Committee, and all animals received humane care in accordance with institutional guidelines and the criteria outlined in the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (prepared by the National Academy of Sciences and published by the NIH; publication 86-23, revised 1985).

Histological Examination and IHC Analysis

Liver histological examination, hepatocellular bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation, and immunohistochemistry analysis for cyclin D1 were assessed as described previously.1, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 For BrdU analyses, animals were administered an i.p. injection of 100 mg/kg of BrdU (Sigma-Aldrich) 1 hour before sacrifice. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded liver tissue was stained either with hematoxylin and eosin or for nuclear BrdU incorporation. Hepatocellular nuclear BrdU labeling and mitoses were quantified by examination of at least three random ×400 fields and at least 300 cells and nuclei in each tissue section. Primary antibodies for immunohistochemistry analysis included BrdU (catalog number OBT0030; Accurate Chemical & Scientific Corp., Westbury, NY) and cyclin D1 (catalog number RB-9041; Thermo Scientific, Rochester, NY).

Serum Metabolite and Plasma Hormone Analyses

Concentrations of serum amino acids were determined by the St. Louis Children's Hospital Core Laboratory as previously described.19, 20, 21 Serum free fatty acids and hepatic triglycerides were quantified as previously described.10 Plasma insulin was determined by quantitative fluorescent immunoassay (Singulex, Alameda, CA) and glucagon by radioimmunoassay (Millipore, Billerica, MA) according to the manufacturer's instructions for each assay, by the Washington University Medical School Core Laboratory for Clinical Studies.

RT-qPCR Gene Expression Analysis

Hepatic expression of specific genes was characterized using real-time semi-quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR) as described previously.1, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 Briefly, total liver RNA purified using the Trizol method (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was reverse-transcribed to cDNA, an aliquot of which was added to a reaction mixture containing iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and gene-specific forward and reverse primers. Quantification of cDNA was conducted by monitoring increased SYBR fluorescence during exponential phase amplification in a real-time PCR MxPro3005 machine (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), using the comparative threshold method.22 Data were standardized to the expression of β2-microglobulin, which is commonly used as a reference gene in analyses of liver regeneration23, 24, 25 and exhibits an expression pattern homologous to that of other genes used for this purpose (eg, β-actin26 and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase27), to calculate fold-differences in gene expression. Specificity was verified for each gene using melt-curves and by simultaneous analysis of a reaction mixture containing all components except reverse transcriptase. Gene-specific primers for RT-qPCR studies are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Gene-Specific Oligonucleotide Primers Used in This Study

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| RT-qPCR | ||

| B2M | 5′-CCAGAAAACCCCTCAAATTCAAG-3′ | 5′-AGTTCAGTATGTTCGGCTTCCC-3′ |

| Bcr | 5′-GGTTGTGGTGTCTGAGGCTA-3′ | 5′-GGTGGTGTTCCAAACGAGGA-3′ |

| Bik | 5′-CCTCATGGAGTGCGTGGAAG-3′ | 5′-CTGTAGGTGACAGCGAGTCT-3′ |

| Bmf | 5′-CAGACCAGTTCCATCGGCTT-3′ | 5′-TGTTCAGGGCGAGGTTTTGA-3′ |

| Cxadr | 5′-ATGGCTGATATCCCCGTCTG-3′ | 5′-TCGCCAGACTTGACATCGTT-3′ |

| Ccnd1 | 5′-GAAGGAGACCATTCCCTTGA-3′ | 5′-GTTCACCAGAAGCAGTTCCA-3′ |

| Ccne1 | 5′-ACGGGTGAGGTGCTGATGCCT-3′ | 5′-AGCAGAAGCAGCGAGGACACC-3′ |

| Ccna2 | 5′-ACAGAGTGTGAAGATGCCCTGGCT-3′ | 5′-AGCATGTGGTGATTCAAAACTGCCA-3′ |

| Ccnb1 | 5′-AGGCTGCTTCAGGAGACCATGT-3′ | 5′-TGGCCGTTACACCGACCAGC-3′ |

| Foxo3 | 5′-AAACGGCTCACTTTGTCCCA-3′ | 5′-ATTCTGAACGCGCATGAAGC-3′ |

| Gclc | 5′-GATGTGGACACCCGATGCAG-3′ | 5′-CTCTCTCATCCACCTGGCAA-3′ |

| Pim1 | 5′-CTCATCGACTTCGGGTCGG-3′ | 5′-AGCGATGGTAGCGAATCCAC-3′ |

| PPARγ1 | 5′-GAAAGAAGCGGTGAACCACTGA-3′ | 5′-TCCGAAGTTGGTGGGCCAGA-3′ |

| PPARγ2 | 5′-CCCAGAGCATGGTGCCTTCGC-3′ | 5′-TCCGAAGTTGGTGGGCCAGA-3′ |

| p21 (Cdkn1a) | 5′-GCTGTCTTGCACTCTGGTGT-3′ | 5′-CTGCGCTTGGAGTGATAGAA-3′ |

| p27 (Cdkn1b) | 5′-TCTCAGGCAAACTCTGAGGA-3′ | 5′-CTTCCTCATCCCTGGACACT-3′ |

| p15 (Ink4b) | 5′-CTTCGGGAGGCGCCCAATCC-3′ | 5′-GCTGCGTCGTGCACAGGTCT-3′ |

| p16 (Ink4a) | 5′-GCGTTCCGCTGGGTGCTCTT-3′ | 5′-GCTCTTGGGATTGGCCGCGA-3′ |

| p18 (Ink4c) | 5′-TGGATTTGGGAGAACTGCGCTGC-3′ | 5′-GCCTGGAACTCCAGCAAAGCCT-3′ |

| p19 (Ink4d) | 5′-TCCTGACGCCCTGAACCGCT-3′ | 5′-TGCGAGCCGCATCATGCACA-3′ |

| Skp2 | 5′-ACACCTCTCGCTCAGCCGGT-3′ | 5′-TGAAGGGTTCCCTCTGGCACGA-3′ |

| Sik1 | 5′-GGGAGGTCCAGCTCATGAAA-3′ | 5′-GTGCCCGTTGGAAGTCAGAT-3′ |

| Tcf7l2 (Tcf4) | 5′-AAACAGCTCCTCCGATTCCG-3′ | 5′-AAAGAGCCCTCCATCTTGCC-3′ |

| Wnt5a | 5′-GGCAGGGTGATGCAAATAGG-3′ | 5′-ACAGGTAGACAGCTCGCCC-3′ |

| Wnt5b | 5′-AACTTTGCCAAGGGATCGGA-3′ | 5′-GACTCCGTGACATTTGCAGG-3′ |

| ChIP-qPCR | ||

| Ccnd1 | 5′-TTACAGGCTGCTAGCTTGGG-3′ | 5′-ATACCGAGTCCTAGCAACGC-3′ |

ChIP-qPCR, real-time quantitative chromatin immunoprecipitation PCR; RT-qPCR, real-time quantitative RT-PCR.

Protein Immunoblot Analysis

Protein immunoblot studies were conducted on whole tissue lysates using standard methodology and as described previously.1, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 Briefly, equal quantities of protein from pooled or individual replicate samples for each examined experimental condition were subjected to denaturing SDS-PAGE and electrophoretic transfer to nitrocellulose. Filters were probed with primary antibodies followed by appropriate infrared fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies (Li-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE), then imaged and quantified using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (Li-Cor Biosciences). Primary antibodies for immunoblot included total glycogen synthase kinase (Gsk)3β (catalog number 9315; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Beverly, MA), phospho-Gsk3β (Ser9, catalog number 9323; Cell Signaling Technology), total Akt (catalog number 4691; Cell Signaling Technology), phospho-Akt (Thr308, catalog number 13038; Cell Signaling Technology), phospho-Akt (Ser473, catalog number 4060; Cell Signaling Technology), total cAMP response element–binding protein (Creb; catalog number 9197; Cell Signaling Technology), phospho-Creb (Ser133, catalog number 9198; Cell Signaling Technology), cyclin D1 (catalog number 06-137; Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY), p21 (catalog number sc-471; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), p27 (catalog number 2552; Cell Signaling Technology), total peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (Pparγ; catalog number sc-7196; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Pparγ2 (catalog number ab45036; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh; catalog number ab8245; Abcam).

Acetyl Histone ChIP-qPCR and ChIP-Seq Analyses

Chromatin immunoprecipitation of histone H3 acetylated on K9 (ie, Ac-H3K9 ChIP) from liver tissue was performed as previously described.15, 16 Briefly, frozen liver was minced, cross-linked in 1% formaldehyde, homogenized, and suspended in nuclear lysis buffer in the presence of protease inhibitors, then centrifuged to recover chromatin, which was sheared in a Bioruptor Sonicator (Diagenode, Denville, NJ) to generate uniform 100- to 500-bp fragments. Equal quantities of chromatin (based on protein content) were immunoprecipitated using a ChIP-grade antibody against Ac-H3K9 (catalog number ab10812; Abcam) or rabbit IgG as nonspecific control. Each lot of the anti–Ac-H3K9 antibody was validated for specificity by dot blot against a panel of unmodified, acetylated, and methylated peptides and by immunoblot against liver tissue (as recommended by Egelhofer et al28). DNA from immunoprecipitated chromatin and corresponding input samples (ie, sheared chromatin before immunoprecipitation) were subjected to qPCR (ie, ChIP-qPCR) as described previously.16 These analyses were performed using the promoter-specific primers listed in Table 1 and by normalizing signal present in the Ac-H3K9 immunoprecipitated material to that in input material. For ChIP sequencing (Seq), DNA samples recovered from immunoprecipitated chromatin and corresponding inputs were also subjected to sequencing (i.e. ChIP-Seq). These samples were submitted to the Washington University Genome Technology Access Center for blunt ending, adaptor ligation, size selection, and amplification according to established protocols. These libraries were sequenced using the HiSeq-2500 sequencing system (Illumina, San Diego, CA) as single 50-bp reads. Raw data were demultiplexed and aligned to the most recent mouse reference genome assembly using Novoalign version 2.08.02 (Novocraft, Selangor, Malaysia). Sequence peaks were identified using Model-based Analysis for ChIP-Seq software (MACS; http://liulab.dfci.harvard.edu/MACS, last accessed 1.4.2 20120305).29 Determination of significant differences in the abundance of peak sequences between experimental groups was performed with DiffBind, an open-source Bioconductor package that utilizes edgeR software version 3.4.2 for statistical analysis of replicated sequence count data (https://www.bioconductor.org/about, last accessed October 27, 2015).30, 31 Genes identified as differentially acetylated were analyzed by gene ontology and other classification schemes using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) bioinformatics database (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov, last accessed October 19, 2015).32, 33 DNA sequence data sets from the ChIP-Seq studies reported here have been deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus34 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo; accession number GSE71496).

Statistical Analysis

ChIP-Seq data were analyzed as described previously.15 Briefly, Benjamini and Hochberg false discovery rate thresholds (q values) were used for identifying DNA sequences (and corresponding genes) as significantly differentially acetylated between liver replicates from dextrose- and vehicle-infused mice (using the data analysis pipeline described in Acetyl Histone ChIP-qPCR and ChIP-Seq Analyses and previously15). Supplemental Table S1 lists the specific false discovery rate q values calculated for each sequence (and corresponding gene) on which the differential acetylation analysis was performed. All other data were analyzed using PASW Statistics version 18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Numerical data comparisons between groups were conducted using the unpaired Student's t-test for pairwise comparisons and analysis of variance for multiple groups with Tukey's test used for post hoc comparisons. Rates and proportions were compared between groups using χ2 analysis. α < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data are reported as means ± SEM.

Results

Identification of a Parenteral Dextrose-Infusion Regimen That Delays PH-Induced Hypoglycemia

Mice subjected to PH develop hypoglycemia within 3 to 6 hours after surgery.5 To delay the onset of such hypoglycemia, different regimens of i.p. dextrose infusion were tested in pilot studies. These analyses showed that i.p. delivery of dextrose at a GIR of 25 μg/g per minute, beginning at the time of PH and adjusted as described in Parenteral Dextrose Infusion, was well-tolerated and associated with brief but modest hyperglycemia 2 hours after PH, with dextrose-infused mice subsequently remaining euglycemic over the ensuing 14 hours (Figure 1A). In contrast, vehicle-infused controls developed PH-induced hypoglycemia consistent with our previously published data,5 with significantly reduced blood glucose observed within 2 to 4 hours of PH (Figure 1A). By 16 to 20 hours after surgery, the dextrose-infused mice displayed hypoglycemia comparable to that seen in the controls. Such hypoglycemia was preceded by increased plasma insulin but without effect on glucagon at 12 hours after PH (Figure 1B). Both cohorts subsequently remained similarly hypoglycemic throughout the remainder of the experiment. The results of these studies define a parenteral regimen of dextrose infusion that reproducibly delays PH-induced hypoglycemia in mice. They also show that increased plasma insulin precedes the onset of hypoglycemia in the glucose-infused animals.

Figure 1.

Delaying partial hepatectomy (PH)-induced hypoglycemia postpones regenerative hepatocellular proliferation. A: Blood glucose values before and after PH in dextrose- and vehicle-treated mice (controls). Blood glucose concentrations in all controls after PH and in dextrose-treated mice at 18 and 22 to 60 hours after PH are significantly lower than those in unoperated (ie, 0-hour) mice. Blood glucose values in dextrose-treated mice at 2 to 14 hours and 18 hours after PH are significantly different from those in corresponding control mice at those time points. The strain-specific, nonfasting, normal blood glucose of male C57BL6/J mice is 198 ± 14 mg/dL, as reported in the Mouse Phenome Database (Jackson Laboratory). B: Plasma insulin and glucagon. C and D: Hepatocellular bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU). E: Liver/body mass ratio. F: Representative hematoxylin and eosin–stained liver sections from dextrose-infused and control mice. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 3 to 8 replicates per time point and treatment group. ∗P < 0.05 versus control (B) or corresponding control (C and E); ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 versus corresponding control; †P < 0.05, ††P < 0.01, and †††P < 0.001 versus 0 hour; ‡P < 0.05 versus corresponding control and 24-hour dextrose; ‡‡P < 0.01 versus 24-hour control; §§§P < 0.001 versus 12-hour control. Scale bars = 100 μm.

Delaying PH-Induced Hypoglycemia Postpones Hepatic Regeneration

Next, the effect of parenteral dextrose infusion on PH-induced liver regeneration was characterized. The results showed that regenerative hepatocellular DNA replication, as assessed by nuclear BrdU incorporation (Figure 1, C and D), and recovery of liver/body mass ratio (Figure 1E) were postponed by a time interval similar to the delay in onset of hypoglycemia in dextrose-infused mice. Nonetheless, liver histological examination was otherwise comparable between dextrose-treated and control mice (Figure 1F). By 72 hours after PH, the liver/body mass ratio was comparable in dextrose-treated and control mice (Figure 1E). Thus, a parenteral dextrose infusion regimen that delays PH-induced hypoglycemia comparably postpones regenerative hepatocellular proliferation and recovery of liver/body mass.

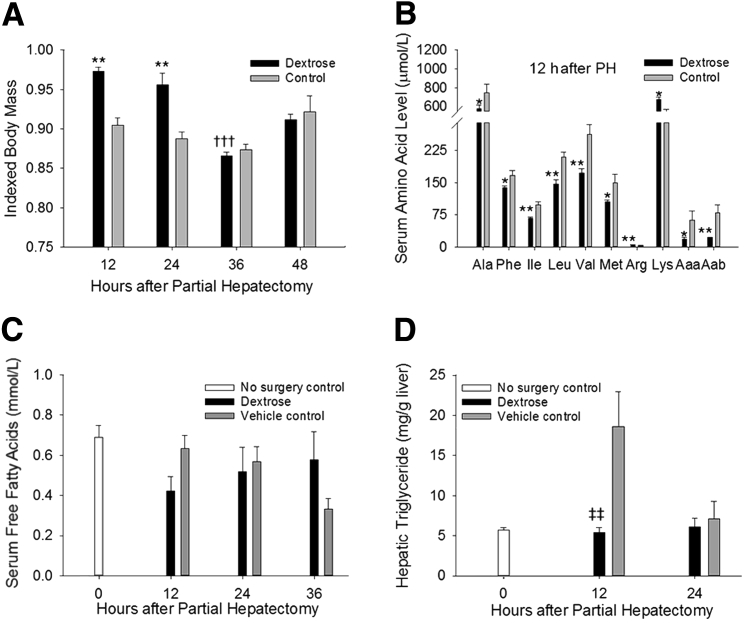

Parenteral Dextrose Infusion Suppresses the Stereotypical Metabolic Response to PH-Induced Hepatic Insufficiency

The hypoglycemia that occurs in response to PH is typically followed by systemic catabolism and accumulation of specific metabolites in the circulation and in regenerating liver.3, 6, 8 To define the role of PH-induced hypoglycemia in promoting these metabolic alterations, the influence of dextrose infusion on such changes was determined. The results showed that delaying hypoglycemia postponed the early PH-induced loss of body mass that characteristically occurs in this model (Figure 2A). Early regenerative changes in circulating amino acid levels were also disrupted by dextrose infusion, with decreased serum Ala, Phe, branched chain amino acids (Ile, Leu, Val), Met, α-NH2-adipic acid, and α-NH2-butyrate and increased Arg and Lys observed at 12 hours after PH in dextrose-infused versus control animals (Figure 2B). PH-induced elevations in serum free fatty acids (Figure 2C) and hepatic triglycerides (Figure 2D) were similarly suppressed by dextrose infusion at this time point. Thus, delaying hypoglycemia postpones elements of the stereotypical metabolic response to hepatic insufficiency in this model of liver regeneration.

Figure 2.

Postponing partial hepatectomy (PH)-induced hypoglycemia delays the metabolic response to liver resection–induced hepatic insufficiency. A: Body mass (indexed to initial body mass). B: Serum amino acid levels. C: Serum free fatty acid levels. P = 0.05 versus control. D: Hepatic triglyceride levels. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 3 to 8 replicates per time point per treatment group. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 versus control; †††P < 0.001 versus 12-hour dextrose; ‡‡P < 0.01 versus vehicle control. Aaa, α-NH2-adipic acid; Aab, α-NH2-butyrate.

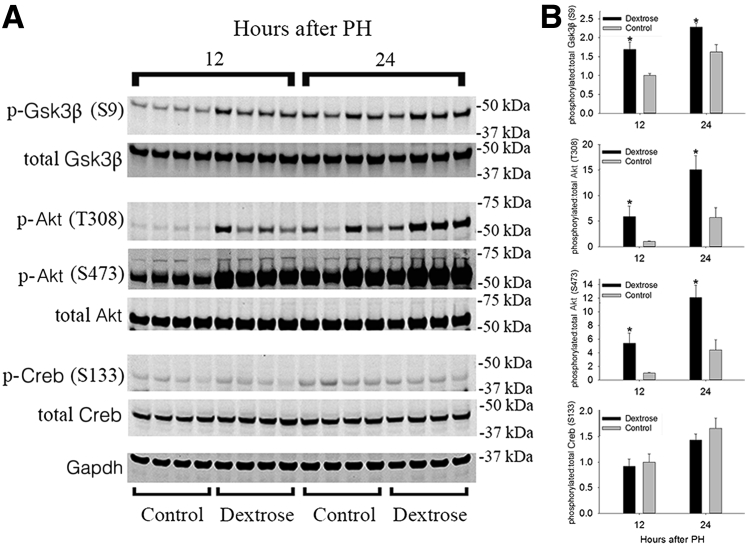

Delaying PH-Induced Hypoglycemia Augments Phosphorylation of Hepatic Gsk3β and Akt

Many signaling pathways involved in the regulation of cell proliferation are also influenced by metabolism.1, 3 For example, phosphorylation-dependent changes in the activities of GSK3β, protein kinase A (PKA), and protein kinase B (ie, AKT) occur in regenerating liver and are metabolically regulated.1, 3 Therefore, the effects of delaying PH-induced hypoglycemia on the regulation of hepatic Gsk3β, Pka, and Akt were investigated in this model. Immunoblot analyses of whole liver showed increased levels of Ser9 (S9) phosphorylation of Gsk3β (a kinase-inactivating modification) in dextrose-infused versus control animals 12 to 24 hours after PH (Figure 3 and Supplemental Figure S1). This finding is consistent with the suppressive effect that supplemental glucose would be predicted to have on GSK3β-dependent inhibition of glycogen synthase activity.35 Comparable investigation of hepatic Akt showed that this enzyme was hyperphosphorylated on Thr 308 (T308) and Ser 473 (S473) in dextrose-treated versus control animals 12 to 24 hours after PH (Figure 3 and Supplemental Figure S1). That result was concordant with the elevated plasma insulin levels observed in dextrose-infused mice (Figure 1B). Finally, hepatic Pka activity was indirectly investigated by immunoblot analyses using an antibody against the phosphorylated form of the Pka substrate Creb. This analysis did not demonstrate any apparent effects of parenteral dextrose infusion on PH-induced changes in hepatic levels of Creb phosphorylated on Ser 133 (S133) at these time points (Figure 3 and Supplemental Figure S1). Taken together, these data demonstrate specific effects of postponing PH-induced hypoglycemia on hepatic phosphorylation of metabolically regulated kinases involved in the control of liver regeneration.

Figure 3.

Delaying partial hepatectomy (PH)-induced hypoglycemia alters glycogen synthase kinase (Gsk)3β and Akt phosphorylation. Protein immunoblot analyses (A) and corresponding quantification (B) of hepatic levels of phosphorylated (p-) and total Gsk3β, Akt, and cAMP response element–binding protein (Creb). Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 4 replicates per time point per treatment group. ∗P < 0.05 versus corresponding control.

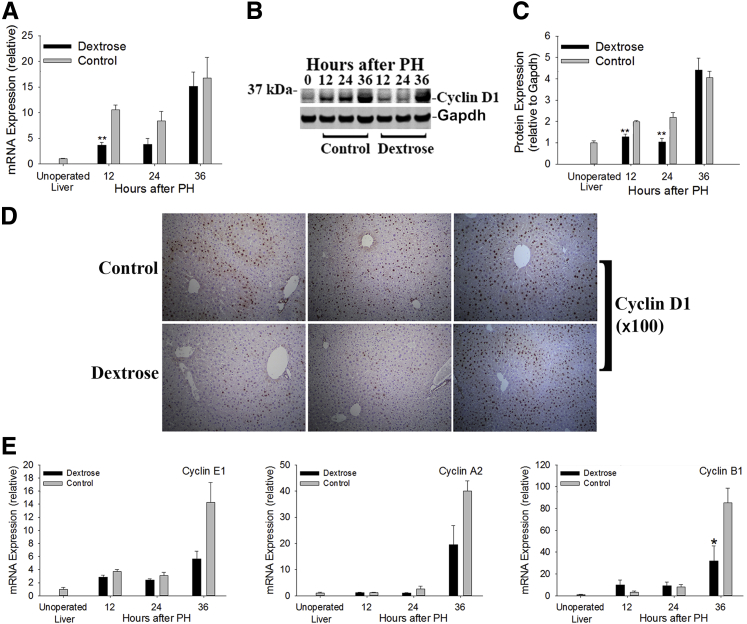

Postponing PH-Induced Hypoglycemia Delays Hepatic Cyclin D1 Gene Acetylation and Expression in Early Regenerating Liver

Next, the influence of delaying hypoglycemia on hepatocellular cell cycle progression was determined. Cyclin D1 expression, which is induced during and promotes early G1 progression, was examined first. The results showed that regenerative induction of cyclin D1 mRNA and protein expression were postponed by dextrose infusion (Figure 4, A–D), with the interval of such delay comparable to the lag in onset of PH-induced hypoglycemia in these animals (Figure 1A). Similarly, hepatic mRNA expression of cyclins E1 and A2, which are typically subsequently induced in regenerating liver and regulate progression through G1 and S stages of the cell cycle,1 showed a trend of suppression (P ≤ 0.07), and cyclin B1 expression was significantly reduced 36 hours after PH in the dextrose-infused mice (Figure 4E). These data show that delaying PH-induced hypoglycemia postpones regenerative induction of hepatic cyclin expression.

Figure 4.

Glycemic regulation of regenerative hepatic cyclin expression. Hepatic cyclin D1 mRNA (A) and protein (B and C) expression. D: Representative IHC analysis of hepatic cyclin D1 expression. E: Hepatic mRNA expression of cyclins E1, A2, and B1. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 3 to 8 replicates per time point per treatment group; the immunoblot in B shows equal quantities of protein pooled from replicates for each time point and treatment group. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 versus control. Gapdh, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

To investigate the molecular mechanisms linking glycemia to cyclin D1 expression in regenerating liver, the impact of parenteral dextrose infusion on PH-induced cyclin D1 gene histone acetylation was assessed. This analysis was informed by our recently published characterization of regenerative changes in the liver histone acetylome.15 In that study, immunoprecipitation of chromatin for Ac-H3K9, an epigenomic mark of transcriptional activation,36 combined with next-generation DNA sequencing (ie, Ac-H3K9 ChIP-Seq) identified specific cyclin D1 gene (Ccnd1) promoter sequences regulated by increased histone acetylation in regenerating liver 12 hours after PH. Those sequences were targeted here for Ac-H3K9 ChIP-qPCR determination of the effects of dextrose infusion on Ccnd1-associated liver histone acetylation at this time point. The results showed that delaying PH-induced hypoglycemia suppressed regenerative hyperacetylation of Ccnd1 (Figure 5A). Genome-wide Ac-H3K9 ChIP-Seq was subsequently conducted, both to confirm this finding in an unbiased way and to more broadly characterize the influence of parenteral dextrose supplementation on early regenerative changes in the liver histone acetylome. This experiment identified 947 deacetylated and 1217 hyperacetylated gene sequences in dextrose- versus vehicle-infused mouse liver (using q < 0.1) (Table 2 and Supplemental Table S1). Those sequences corresponded to 788 and 996 unique genes, respectively (ie, several genes are represented by multiple distinct sequences in this data set). Next, these gene lists were classified into functional gene categories using the DAVID bioinformatics database32, 33 and an analytical approach identical to that used in our recent report.15 Our prior study showed significant functional enrichment of genes hyperacetylated after PH for those associated with cell cycle regulation. Conversely, genes deacetylated in regenerating liver were enriched for those linked to apoptosis (using q < 0.115). In contrast to those results, genes identified here as hyper- or deacetylated in regenerating liver by dextrose infusion after PH were not significantly enriched for either cell cycle or apoptosis functions (data not shown). Nonetheless, further comparison of the results obtained here with those from our recently published analysis identified specific individual proliferative and cell death–associated genes whose typical PH-induced regulation by changes in liver histone acetylation15 was reversed by dextrose supplementation (Table 2). For example, consistent with the ChIP-qPCR results shown in Figure 5A, Ccnd1 was among the genes identified by Ac-H3K9 ChIP-Seq as deacetylated by dextrose infusion after PH (Figure 5B, Table 2, and Supplemental Table S1). Other proliferative genes whose PH-induced hyperacetylation was also reversed by dextrose supplementation included the β-catenin binding partner and transcriptional activator Tcf7l2 and the Pka- and Creb-regulated salt inducible kinase 1 (Sik1). Conversely, histone acetylation of the antiproliferative (and proapoptotic) transcription factor Foxo3, which we previously reported to be diminished during early normal regeneration,15 was augmented by supplemental dextrose here (Table 2 and Supplemental Table S1). Thus, delaying the onset of PH-induced hypoglycemia broadly alters regenerative changes in liver histone acetylation and specifically disrupts epigenomic induction of cyclin D1 expression in early regenerating liver.

Figure 5.

Partial hepatectomy (PH)-induced hypoglycemia regulates regenerative cyclin D1 gene acetylation. A: Histone H3 acetylated on K9 (Ac-H3K9) real-time quantitative chromatin immunoprecipitation PCR (ChIP-qPCR) targeting the cyclin D1 gene (Ccnd1) sequence indicated by the gray bar in B. B: The University of California at Santa Cruz (UCSC) mm10 Ccnd1 gene map is shown above data depicting the abundances of histone acetylated sequences at 12 hours after PH in dextrose-infused and control mice. Below those data, the white bar with black border indicates sequences identified as hyperacetylated at 12 hours after PH versus sham surgery from our recently published study15; the grey bar identifies the sequence targeted for qPCR in A; and the black bar indicates sequences significantly deacetylated at 12 hours after PH in regenerating liver from dextrose-infused versus control mice (q < 0.1) (Supplemental Table S1). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM percentages to input. n = 3 to 6 mice per group. ∗P < 0.05 versus control.

Table 2.

Summary of Differentially Acetylated Genes 12 h after PH in Livers from Dextrose-Infused versus Control Mice

| Effect of dextrose | Total genes (unique)∗ | Genes with typical regenerative response reversed by dextrose |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell proliferation genes | Cell death genes | ||

| Decreased acetylation | 947 (788) | Bcr, Ccnd1, Cxadr, Sik1, Tcf7l2, Wnt5a, Wnt5b | None |

| Increased acetylation | 1217 (966) | Foxo3, Pim1 | Bik, Bmf, Foxo3, Gclc, Pim1 |

The analysis was conducted on livers from six replicates per treatment group and false discovery rate (q) <0.1. All genes identified as differentially acetylated are listed by q value in Supplemental Table S1.

PH, partial hepatectomy.

Identified with Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery bioinformatics database as described in the text and previously,15 using GOTERM_BP_ALL, PANTHER_BP_ALL, KEGG_PATHWAY, PANTHER_PATHWAY on all de- or hyperacetylated genes, respectively.

Delaying PH-Induced Hypoglycemia Augments Hepatic CDKI and PPARγ Expression during Early Regeneration

Hepatic cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor (CDKI) expression is highly regulated during liver regeneration.1 Therefore, the influence of parenteral dextrose infusion on PH-induced changes in expression of specific CDKIs was investigated here. The results showed that dextrose infusion increased hepatic p21 (ie, Cdkn1a) and p27 (ie, Cdkn1b) mRNA as well as p27 protein expression after PH (Figure 6, A–C). Degradation of p21 and p27 proteins occurs during cell cycle progression and is promoted by induction of expression of the E3 ubiquitin ligase S-phase kinase-associated protein (Skp)2. Furthermore, hepatic Skp2 expression is normally induced during early liver regeneration by PH.9, 37, 38, 39 Examination of such regulation here showed that induction of Skp2 was suppressed in dextrose-treated animals (Figure 6D). Expression of specific inhibitor of kinase 4 CDKIs is also regulated during normal liver regeneration16, 40; however, dextrose infusion does not alter such expression in early regenerating liver (data not shown). Together, these data implicate glycemic influences on Skp2-dependent p27 protein degradation as a candidate contributor to the antiregenerative effects of parenteral dextrose infusion (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Metabolic regulation of hepatic cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, S-phase kinase-associated protein (Skp)2, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (Pparγ) expression during partial hepatectomy (PH)-induced liver regeneration. A–C: Hepatic p21 and p27 mRNA (A) and p27 protein (B and C). D: Skp2 mRNA. E–G: Pparγ1 and Pparγ2 mRNA (E) and PPARγ2 protein (F and G). n = 3 to 8 mice per time point per group and indexed to expression in 12-hour controls; n = 4 (B, C, F, G, replicates). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 versus control. Gapdh, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Figure 7.

A metabolic model of liver regeneration. Candidate mechanisms linking metabolism and regeneration suggested by the new data reported here and by previously published data2, 3, 4 are indicated by dashed and solid arrows, respectively. PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma; Skp2, S-phase kinase-associated protein 2.

We previously reported that Pparγ-activating thiazolidinediones suppress PH-induced changes in hepatic cyclin D1 and Skp2 expression and inhibit mouse liver regeneration9 and that liver-specific Pparγ null mice exhibit accelerated regeneration.10 Therefore, the impact of parenteral dextrose infusion on hepatic Pparγ expression was characterized here. The results showed that hepatic mRNA expression of the Pparγ2 (but not the Pparγ1) isoform was augmented by supplemental dextrose in this model (Figure 6E). Immunoblot analysis using a Pparγ2-specific antibody showed that Pparγ protein levels were also increased by glucose supplementation in regenerating liver (Figure 6, F and G). Thus, alterations in PPARγ activity could also contribute to the effects of dextrose supplementation on liver regeneration (Figure 7).

Discussion

Many studies implicate the metabolic response to hepatic insufficiency as an important source of proregenerative signals in experimental models of liver regeneration.2, 3, 4 Nonetheless, the specific mechanisms by which metabolism affects regeneration remain incompletely understood. The analyses reported here were undertaken to investigate the functional importance and mechanistic basis of the influence of PH-induced hypoglycemia on the regulation of liver regeneration. Our studies show that regenerative recovery of the liver is postponed by an interval of time comparable to the delay in onset of PH-induced hypoglycemia in our mouse model of parenteral dextrose infusion. These analyses also identified specific molecular signals known to influence liver regeneration that are dysregulated by such dextrose supplementation. For example, PH-induced effects on induction of hepatic expression of cyclin D1 and Skp2 and suppression of Pparγ2 and p27 expression are each disrupted when PH-induced hypoglycemia is delayed. A previously published study showed that the PPARγ2 isoform inhibits cyclin D1 expression in hepatocytes.41 Other studies have demonstrated antagonistic crosstalk between PPARγ and β-catenin signaling,42 with the latter strongly implicated in the hepatic regenerative regulation of cyclin D1 expression.18, 43, 44 Together with the new data reported here, those observations suggest a model of liver regeneration in which PH-induced hypoglycemia (and/or perhaps subsequent alterations in metabolism) promote liver regeneration by inducing specific proregenerative signals and suppressing certain antiregenerative pathways (Figure 7).

Other signaling pathways implicated in the regulation of liver regeneration are also known to be influenced by metabolism2, 3, 4; however, metabolic regulation of such pathways during regeneration has generally not been established. The influence of parenteral dextrose infusion on regenerative regulation of some of these signals was investigated here. Examination of Gsk3β, whose biological role in glycemic control and cell proliferation is well-established,35 demonstrated that parenteral dextrose infusion augmented kinase-inhibiting S9 phosphorylation of this enzyme. Recent studies have also shown that pharmacological or genetic inhibition of GSK3β inhibits liver regeneration by disrupting regenerative regulation of CCAAT/enhancer binding protein α45 and the Snail transcription factor.46 Thus, increased GSK3β S9 phosphorylation and correspondingly reduced kinase activity might contribute to the inhibition of liver regeneration by parenteral dextrose infusion. However, this conclusion is difficult to reconcile with the known antiproliferative effects of GSK3β-regulated phosphorylation and proteasomal degradation of regeneration-promoting β-catenin and cyclin D1.35 One possible resolution of this apparent paradox is suggested by a study reporting that insulin and Wnt-signaling regulate GSK3β through distinct mechanisms that lead to different downstream signaling events.47 Thus, the enhanced Gsk3β S9 phosphorylation in dextrose-supplemented animals observed here may not directly impact β-catenin–dependent regulation of cyclin D1 expression. Future studies should be conducted to further investigate these provocative considerations, which raise the possibility that at least two different subcellular pools of GSK3β exist and that these pools are divergently regulated by altered metabolism in regenerating liver.

Our data also show that the delay in regenerative induction of hepatic cyclin D1 expression in mice administered parenteral dextrose correlates with postponement of cyclin D1 promoter histone acetylation. Such epigenomic regulation could occur through glycemic effects on histone acetyltransferases at the cyclin D1 promoter in regenerating liver. Both TCF7L2 (also known as TCF4, a transcription-activating β-catenin binding partner) and Creb bind the cyclin D1 promoter and interact with the histone acetyltransferase Creb-binding protein (CBP).48 CBP binding to and transcriptional regulation by CREB are controlled, in part, by CREB phosphorylation. Such phosphorylation is catalyzed by PKA and other hormone- and growth factor–activated kinases.49 β-Catenin–dependent transcriptional activity is also stimulated by PKA-mediated phosphorylation.50, 51 Moreover, hypoglycemia-induced glucagon, catecholamine, prostaglandin, and perhaps other signals trigger G-protein–coupled receptors to activate adenylate cyclase and, thereby, PKA. Thus, transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2) or Creb or both might be metabolically regulated to direct CBP to the cyclin D1 promoter during normal regeneration. Based on our data and these considerations, ChIP-based experiments to define the impact of delaying PH-induced hypoglycemia on patterns of binding by these (and other) transcriptional regulators to the cyclin D1 promoter in regenerating liver should be conducted to further characterize the metabolic mechanisms that regulate liver regeneration.

Not exclusive of the considerations raised in the Discussion above, PH-induced hypoglycemia might also indirectly promote (and parenteral dextrose infusion suppress) regenerative hyperacetylation of the cyclin D1 gene promoter by affecting histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity. We recently reported the isoform-specific regulation of zinc-dependent HDACs (Zn-HDACs) during normal liver regeneration and the antiregenerative effect of global Zn-HDAC inhibition.16 That analysis showed that PH induces hepatic expression of specific Zn-HDACs, suppresses that of others, and promotes the transient nuclear localization of HDAC5 in early regenerating liver. Notably, hypoglycemia also promotes HDAC5 nuclear localization in other models.52 Recent studies also show that the NAD-dependent HDAC sirtuin 1 exerts antiregenerative activity in some settings but is proregenerative in others.53, 54 Thus, further efforts to define glycemic influences on Zn- and NAD-dependent HDACs and the function of such regulation during liver regeneration should also be pursued to elucidate mechanisms linking metabolic and epigenomic regulation of liver regeneration.

Delaying PH-induced hypoglycemia not only disrupts proregenerative cyclin D1 induction but also delays PH-stimulated suppression of antiproliferative signals. For example, hepatic p27 protein levels, which normally decline during early liver regeneration,5, 6, 9, 10, 16 are augmented by parenteral dextrose infusion. Degradation of p27 protein is promoted by the E3 ubiquitin ligase Skp2,38, 39 and Skp2 expression is normally induced during early liver regeneration.9 However, such expression is suppressed by parenteral dextrose infusion. We previously reported that regenerative expression of Skp2 is also inhibited by Pparγ-activating thiazolidinediones9 and showed that liver-specific Pparγ knockout mice exhibit accelerated regeneration.10 We also showed that Pparγ2 mRNA expression is normally down-regulated in early regenerating liver.10 Together with these previously published data, the findings reported here showing that dextrose infusion augments Pparγ2 expression in regenerating liver implicate glycemic effects on hepatocellular PPARγ activity as a possible mechanism by which metabolism influences liver regeneration (Figure 7). This hypothesis could be tested in future studies by an investigation of the effects of delaying PH-induced hypoglycemia on liver regeneration in liver-specific Pparγ null mice. Another mechanism by which glycemia might affect regenerative regulation of antiproliferative signals is suggested by the recent study reporting that histone acetyltransferase–dependent acetylation of p27 protein (by P300/Creb-binding protein–associated factor) regulates p27 stability by a SKP2-independent mechanism.55 Thus, the previously discussed glycemic influences on histone acetyltransferase or HDAC activity, raised in the Discussion above, might also influence liver regeneration by modulating p27 protein levels.

Finally, our published5 and new data identifying glycemic manipulation as a strategy by which experimental regeneration can be controlled raise the possibility that liver regeneration in humans might be similarly inhibited or accelerated. This consideration has provocative clinical implications. For example, current clinical care of patients with acute liver failure (ALF) emphasizes prevention of hypoglycemia to avoid its significant complications, without as careful consideration of potential detrimental effects of hyperglycemia.56 Preventing hypoglycemia should remain a cornerstone of ALF patient management. However, the data reported here suggest that excess dextrose supplementation might delay regenerative recovery of the liver in ALF, and, thereby, reduce the likelihood of transplant-free survival in such patients. Conversely, an earlier study using a subtotal (85% to 90%) rodent liver resection model, in which regenerative recovery of liver mass is delayed,57 reported that glucose supplementation improves outcomes in that paradigm.58 Thus, clinical research that carefully examines the relationships between glycemia, glucose supplementation, and outcomes in ALF should be conducted. Similarly, studies investigating whether poorer outcomes after liver resection in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease59 are influenced by adverse metabolic effects on hepatic regenerative signals should be considered. Such analyses might suggest clinical intervention trials targeting metabolic strategies to accelerate liver regeneration and improve outcomes in liver diseases in humans.

Acknowledgments

We thank the WUSM Digestive Disease Research Core Center facilities for histology and IHC analysis, the WUSM Genome Technology Access Center for ChIP-Seq genomic analyses, the St. Louis Children's Hospital Core Laboratory for amino acid analyses, and the WUSM Core Laboratory for Clinical Studies for plasma hormone determinations.

Footnotes

Supported by the Children's Discovery Institute of Washington University and St. Louis Children's Hospital (SLCH; D.A.R.); the Department of Pediatrics, Washington University School of Medicine (WUSM); an unrestricted donation from Karsyn's Kause Foundation (D.A.R.); WUSM Digestive Disease Research Core Center grant NIH-NIDDK P30-DK52574; NIH grants 1RO1DK62277 and 1RO1DK100287; and an Endowed Chair for Experimental Pathology (S.P.S.M.). The Genome Technology Access Center, Department of Genetics, WUSM, is partially funded by NCI Cancer Center grant P30CA91842 to the Siteman Cancer Center and ICTS/CTSA (Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences/Clinical and Translational Science Awards) grant UL1TR000448 from the National Center for Research Resources, a component of the NIH, and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research.

Disclosures: None declared.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.10.027.

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Figure S1.

Delaying partial hepatectomy (PH)-induced hypoglycemia alters glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)3β and Akt phosphorylation. Equal quantities of protein from individual replicate samples of whole liver lysate for each experimental condition were pooled and subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analyses for hepatic levels of phosphorylated (p-) and total GSK3β, Akt, and cAMP response element–binding protein (Creb).

References

- 1.Rudnick D.A. Liver regeneration: the developmental biologists approach. Regenerative Medicine Applications in Organ Transplantation. In: Orlando G., Lerut J.P., Soker S., Stratta R.J., editors. Elsevier/Academic Press; Waltham, MA: 2014. pp. 353–374. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rudnick D.A., Davidson N.O. Functional Relationships between lipid metabolism and liver regeneration. Int J Hepatol. 2012;2012:549241. doi: 10.1155/2012/549241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang J., Rudnick D.A. Elucidating the metabolic regulation of liver regeneration. Am J Pathol. 2014;184:309–321. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang J., Rudnick D.A. Elucidating metabolic and epigenetic mechanisms that regulate liver regeneration. Curr Pathobiol Rep. 2015;3:89–98. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weymann A., Hartman E., Gazit V., Wang C., Glauber M., Turmelle Y., Rudnick D.A. p21 is required for dextrose-mediated inhibition of mouse liver regeneration. Hepatology. 2009;50:207–215. doi: 10.1002/hep.22979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gazit V., Weymann A., Hartman E., Finck B.N., Hruz P.W., Tzekov A., Rudnick D.A. Liver regeneration is impaired in lipodystrophic fatty liver dystrophy mice. Hepatology. 2010;52:2109–2117. doi: 10.1002/hep.23920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shteyer E., Liao Y., Muglia L.J., Hruz P.W., Rudnick D.A. Disruption of hepatic adipogenesis is associated with impaired liver regeneration in mice. Hepatology. 2004;40:1322–1332. doi: 10.1002/hep.20462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rudnick D.A., Dietzen D.J., Turmelle Y.P., Shepherd R., Zhang S., Belle S.H., Squires R., Pediatric Acute Liver Failure Study Group Serum alpha-NH-butyric acid may predict spontaneous survival in pediatric acute liver failure. Pediatr Transplant. 2009;13:223–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2008.00998.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turmelle Y.P., Shikapwashya O., Tu S., Hruz P.W., Yan Q., Rudnick D.A. Rosiglitazone inhibits mouse liver regeneration. FASEB J. 2006;20:2609–2611. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6511fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gazit V., Huang J., Weymann A., Rudnick D.A. Analysis of the role of hepatic PPARgamma expression during mouse liver regeneration. Hepatology. 2012;56:1489–1498. doi: 10.1002/hep.25880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rudnick D.A., Liao Y., An J.K., Muglia L.J., Perlmutter D.H., Teckman J.H. Analyses of hepatocellular proliferation in a mouse model of alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency. Hepatology. 2004;39:1048–1055. doi: 10.1002/hep.20118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liao Y., Shikapwashya O.N., Shteyer E., Dieckgraefe B.K., Hruz P.W., Rudnick D.A. Delayed hepatocellular mitotic progression and impaired liver regeneration in early growth response-1-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:43107–43116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407969200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark A., Weymann A., Hartman E., Turmelle Y., Carroll M., Thurman J.M., Holers V.M., Hourcade D.E., Rudnick D.A. Evidence for non-traditional activation of complement factor C3 during murine liver regeneration. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:3125–3132. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang J., Glauber M., Qiu Z., Gazit V., Dietzen D.J., Rudnick D.A. The influence of skeletal muscle on the regulation of liver: body mass and liver regeneration. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:575–582. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang J., Schriefer A.E., Yang W., Cliften P.F., Rudnick D.A. Identification of an epigenetic signature of early mouse liver regeneration that is disrupted by Zn-HDAC inhibition. Epigenetics. 2014;9:1521–1531. doi: 10.4161/15592294.2014.983371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang J., Barr E., Rudnick D.A. Characterization of the regulation and function of zinc-dependent histone deacetylases during rodent liver regeneration. Hepatology. 2013;57:1742–1751. doi: 10.1002/hep.26206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rudnick D.A., Perlmutter D.H., Muglia L.J. Prostaglandins are required for CREB activation and cellular proliferation during liver regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:8885–8890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151217998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang J., Mowry L.E., Nejak-Bowen K.N., Okabe H., Diegel C.R., Lang R.A., Williams B.O., Monga S.P. Beta-catenin signaling in murine liver zonation and regeneration: a Wnt-Wnt situation! Hepatology. 2014;60:964–976. doi: 10.1002/hep.27082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dietzen D.J., Weindel A.L., Carayannopoulos M.O., Landt M., Normansell E.T., Reimschisel T.E., Smith C.H. Rapid comprehensive amino acid analysis by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry: comparison to cation exchange with post-column ninhydrin detection. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2008;22:3481–3488. doi: 10.1002/rcm.3754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dietzen D.J., Weindel A.L. Comprehensive determination of amino acids for diagnosis of inborn errors of metabolism. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;603:27–36. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-459-3_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oladipo O.O., Weindel A.L., Saunders A.N., Dietzen D.J. Impact of premature birth and critical illness on neonatal range of plasma amino acid concentrations determined by LC-MS/MS. Mol Genet Metab. 2011;104:476–479. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schefe J.H., Lehmann K.E., Buschmann I.R., Unger T., Funke-Kaiser H. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR data analysis: current concepts and the novel “gene expression's CT difference” formula. J Mol Med. 2006;84:901–910. doi: 10.1007/s00109-006-0097-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cressman D.E., Greenbaum L.E., DeAngelis R.A., Ciliberto G., Furth E.E., Poli V., Taub R. Liver failure and defective hepatocyte regeneration in interleukin-6-deficient mice. Science. 1996;274:1379–1383. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5291.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamada Y., Kirillova I., Peschon J.J., Fausto N. Initiation of liver growth by tumor necrosis factor: deficient liver regeneration in mice lacking type I tumor necrosis factor receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:1441–1446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenbaum L.E., Li W., Cressman D.E., Peng Y., Ciliberto G., Poli V., Taub R. CCAAT enhancer-binding protein beta is required for normal hepatocyte proliferation in mice after partial hepatectomy. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:996–1007. doi: 10.1172/JCI3135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li W., Liang X., Kellendonk C., Poli V., Taub R. STAT3 contributes to the mitogenic response of hepatocytes during liver regeneration. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:28411–28417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202807200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sakamoto T., Liu Z., Murase N., Ezure T., Yokomuro S., Poli V., Demetris A.J. Mitosis and apoptosis in the liver of interleukin-6-deficient mice after partial hepatectomy. Hepatology. 1999;29:403–411. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Egelhofer T.A., Minoda A., Klugman S., Lee K., Kolasinska-Zwierz P., Alekseyenko A.A., Cheung M.S., Day D.S., Gadel S., Gorchakov A.A., Gu T., Kharchenko P.V., Kuan S., Latorre I., Linder-Basso D., Luu Y., Ngo Q., Perry M., Rechtsteiner A., Riddle N.C., Schwartz Y.B., Shanower G.A., Vielle A., Ahringer J., Elgin S.C., Kuroda M.I., Pirrotta V., Ren B., Strome S., Park P.J., Karpen G.H., Hawkins R.D., Lieb J.D. An assessment of histone-modification antibody quality. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:91–93. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Y., Liu T., Meyer C.A., Eeckhoute J., Johnson D.S., Bernstein B.E., Nusbaum C., Myers R.M., Brown M., Li W., Liu X.S. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS) Genome Biol. 2008;9:R137. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robinson M.D., McCarthy D.J., Smyth G.K. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ross-Innes C.S., Stark R., Teschendorff A.E., Holmes K.A., Ali H.R., Dunning M.J., Brown G.D., Gojis O., Ellis I.O., Green A.R., Ali S., Chin S.F., Palmieri C., Caldas C., Carroll J.S. Differential oestrogen receptor binding is associated with clinical outcome in breast cancer. Nature. 2012;481:389–393. doi: 10.1038/nature10730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang da W., Sherman B.T., Lempicki R.A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang da W., Sherman B.T., Lempicki R.A. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edgar R., Domrachev M., Lash A.E. Gene expression omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:207–210. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kockeritz L., Doble B., Patel S., Woodgett J.R. Glycogen synthase kinase-3—an overview of an over-achieving protein kinase. Curr Drug Targets. 2006;7:1377–1388. doi: 10.2174/1389450110607011377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jayani R.S., Ramanujam P.L., Galande S. Studying histone modifications and their genomic functions by employing chromatin immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting. Methods Cell Biol. 2010;98:35–56. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(10)98002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Minamishima Y.A., Nakayama K., Nakayama K. Recovery of liver mass without proliferation of hepatocytes after partial hepatectomy in Skp2-deficient mice. Cancer Res. 2002;62:995–999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kossatz U., Dietrich N., Zender L., Buer J., Manns M.P., Malek N.P. Skp2-dependent degradation of p27kip1 is essential for cell cycle progression. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2602–2607. doi: 10.1101/gad.321004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Motomura W., Takahashi N., Nagamine M., Sawamukai M., Tanno S., Kohga Y., Okumura T. Growth arrest by troglitazone is mediated by p27Kip1 accumulation, which results from dual inhibition of proteasome activity and Skp2 expression in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Int J Cancer. 2004;108:41–46. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luedde T., Rodriguez M.E., Tacke F., Xiong Y., Brenner D.A., Trautwein C. p18(INK4c) collaborates with other CDK-inhibitory proteins in the regenerating liver. Hepatology. 2003;37:833–841. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharma C., Pradeep A., Pestell R.G., Rana B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma activation modulates cyclin D1 transcription via beta-catenin-independent and cAMP-response element-binding protein-dependent pathways in mouse hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16927–16938. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309045200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Farmer S.R. Regulation of PPARgamma activity during adipogenesis. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29(Suppl 1):S13–S16. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Monga S.P. Role and regulation of beta-catenin signaling during physiological liver growth. Gene Expr. 2014;16:51–62. doi: 10.3727/105221614X13919976902138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tan X., Behari J., Cieply B., Michalopoulos G.K., Monga S.P. Conditional deletion of beta-catenin reveals its role in liver growth and regeneration. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1561–1572. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jin J., Wang G.L., Shi X., Darlington G.J., Timchenko N.A. The age-associated decline of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta plays a critical role in the inhibition of liver regeneration. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:3867–3880. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00456-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sekiya S., Suzuki A. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta-dependent Snail degradation directs hepatocyte proliferation in normal liver regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:11175–11180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016122108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ding V.W., Chen R.H., McCormick F. Differential regulation of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta by insulin and Wnt signaling. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:32475–32481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005342200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Klein E.A., Assoian R.K. Transcriptional regulation of the cyclin D1 gene at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:3853–3857. doi: 10.1242/jcs.039131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Servillo G., Della Fazia M.A., Sassone-Corsi P. Coupling cAMP signaling to transcription in the liver: pivotal role of CREB and CREM. Exp Cell Res. 2002;275:143–154. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taurin S., Sandbo N., Qin Y., Browning D., Dulin N.O. Phosphorylation of beta-catenin by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9971–9976. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508778200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fanti M., Singh S., Ledda-Columbano G.M., Columbano A., Monga S.P. Tri-iodothyronine induces hepatocyte proliferation by protein kinase A-dependent beta-catenin activation in rodents. Hepatology. 2014;59:2309–2320. doi: 10.1002/hep.26775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mihaylova M.M., Vasquez D.S., Ravnskjaer K., Denechaud P.D., Yu R.T., Alvarez J.G., Downes M., Evans R.M., Montminy M., Shaw R.J. Class IIa histone deacetylases are hormone-activated regulators of FOXO and mammalian glucose homeostasis. Cell. 2011;145:607–621. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Garcia-Rodriguez J.L., Barbier-Torres L., Fernandez-Alvarez S., Juan V.G., Monte M.J., Halilbasic E., Herranz D., Alvarez L., Aspichueta P., Marin J.J., Trauner M., Mato J.M., Serrano M., Beraza N., Martinez-Chantar M.L. SIRT1 controls liver regeneration by regulating BA metabolism through FXR and mTOR signaling. Hepatology. 2013;59:1972–1983. doi: 10.1002/hep.26971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jin J., Iakova P., Jiang Y., Medrano E.E., Timchenko N.A. The reduction of SIRT1 in livers of old mice leads to impaired body homeostasis and to inhibition of liver proliferation. Hepatology. 2011;54:989–998. doi: 10.1002/hep.24471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perez-Luna M., Aguasca M., Perearnau A., Serratosa J., Martinez-Balbas M., Jesus P.M., Bachs O. PCAF regulates the stability of the transcriptional regulator and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:6520–6533. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee W.M., Squires R.H., Jr., Nyberg S.L., Doo E., Hoofnagle J.H. Acute liver failure: summary of a workshop. Hepatology. 2008;47:1401–1415. doi: 10.1002/hep.22177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lehmann K., Tschuor C., Rickenbacher A., Jang J.H., Oberkofler C.E., Tschopp O., Schultze S.M., Raptis D.A., Weber A., Graf R., Humar B., Clavien P.A. Liver failure after extended hepatectomy in mice is mediated by a p21-dependent barrier to liver regeneration. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1609–1619. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gaub J., Iversen J. Rat liver regeneration after 90% partial hepatectomy. Hepatology. 1984;4:902–904. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840040519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vetelainen R., van Vliet A., Gouma D.J., van Gulik T.M. Steatosis as a risk factor in liver surgery. Ann Surg. 2007;245:20–30. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000225113.88433.cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.