Abstract

Background

Sub-Saharan African Migrants (SAM) are the second largest group affected by HIV/AIDS in Belgium and the rest of Western Europe. Increasing evidence shows that, more than previously thought, SAM are acquiring HIV in their host countries. This calls for a renewed focus on primary prevention. Yet, knowledge on the magnitude of the HIV epidemic among SAM (HIV prevalence estimates and proportions of undiagnosed HIV infections) and underlying drivers are scarce and limit the development of such interventions.

Objective

By applying a community-based participatory and mixed-methods approach, the TOGETHER project aims to deepen our understanding of HIV transmission dynamics, as well as inform future primary prevention interventions for this target group.

Methods

The TOGETHER project consists of a cross-sectional study to assess HIV prevalence and risk factors among SAM visiting community settings in Antwerp city, Belgium, and links an anonymous electronic self-reported questionnaire to oral fluid samples. Three formative studies informed this method: (1) a social mapping of community settings using an adaptation of the PLACE method; (2) a multiple case study aiming to identify factors that increase risk and vulnerability for HIV infection by triangulating data from life history interviews, lifelines, and patient files; and (3) an acceptability and feasibility study of oral fluid sampling in community settings using participant observations.

Results

Results have been obtained from 4 interlinked studies and will be described in future research.

Conclusions

Combining empirically tested and innovative epidemiological and social science methods, this project provides the first HIV prevalence estimates for a representative sample of SAM residing in a West European city. By triangulating qualitative and quantitative insights, the project will generate an in-depth understanding of the factors that increase risk and vulnerability for HIV infection among SAM. Based on this knowledge, the project will identify priority subgroups within SAM communities and places for HIV prevention. Adopting a community-based participatory approach throughout the full research process should increase community ownership, investment, and mobilization for HIV prevention.

Keywords: HIV, HIV prevention, sub-Saharan African migrants, HIV prevalence, HIV risk factors, mixed methods, community-based participatory research, oral fluid, electronic questionnaire, surveys and questionnaires

Introduction

Background

“Know your epidemic, know your response,” has become the directive of the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS) for intensifying HIV prevention [1]. Sub-Saharan African Migrants (SAM) are the second largest group affected by HIV/AIDS in Belgium [2,3]; however, knowledge on the population’s HIV prevalence and underlying factors that shape the HIV epidemic in SAM communities is scarce. This limits the development of targeted primary prevention interventions. Such interventions have gained importance, since recent evidence shows that increasing proportions of SAM acquire HIV in their European host countries [4-8]. To address this knowledge gap and improve primary prevention for SAM, we developed the TOGETHER Project, which started in January 2012. The project’s study protocol is presented in this paper.

HIV in Belgium’s African Communities: “What Do We Know?”

In Belgium, 27% (n=230) of the newly reported HIV diagnoses in 2013 were in individuals of sub-Saharan African origin [3]. Since in 24% of all reported cases, data on the country of origin was missing, it is assumed that the overall number of new HIV diagnoses among SAM might be underestimated. Yet, it is clear that as communities of SAM are small (1.6% of the Belgian population), HIV disproportionately affects them.

Reported characteristics of newly diagnosed SAM in Belgium are in line with the generalized epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa. In 2013, the majority (64%) were women, heterosexual contact was the main transmission mode (89%), and most (78%) were diagnosed between 20 and 45 years [3]. Patients originated from 31 different countries, the largest groups coming from Cameroon (18%), Democratic Republic of the Congo (12%), and Guinea (9%) (personal communication Sasse, 2015). As in other European countries [2], HIV infections among SAM were usually diagnosed late. Of newly diagnosed SAM, 50% were late presenters, that is, their CD4 cell count was < 350/ml at the time of first diagnosis in Belgium [3]. According to CD4 cell decline simulations, it takes an estimated period of about four years from seroconversion for the CD4 count to reach 350 [9]. During this time, diagnostic opportunities may be missed. However, HIV diagnosis does not automatically translate into direct linkage to care among SAM [10,11]. Denial, coming to terms with diagnosis, not knowing where to go, feeling well and having no symptoms, HIV stigma and discrimination, and fear of medication prevent SAM from accessing care immediately after diagnosis [11].

Late diagnosis and delayed initiation of care not only affect disease prognosis [12], life expectancy [13], and health care costs [14-16], but also lead to an increased risk for onward HIV transmission, due to the prolonged period of unawareness of HIV status and continued high viral load of those not treated [17,18].

Belgian surveillance data show that 10.4% of all SAM diagnosed in 2013 report having acquired HIV in Belgium. Yet, this is based on the physician’s assessment at diagnosis and data are missing for 30% of cases [3]. Evidence from other EU countries suggests that this might be an underestimation. An Italian study among newly arrived immigrants first suggested that HIV infection had been more often acquired in the host country than previously estimated [6]. A study among newly diagnosed Africans in London specified that a quarter to a third of all HIV-positive Africans residing in the UK, and nearly half of HIV-positive African men who have sex with men (MSM), were likely to have acquired HIV in the UK [5]. Mathematical modeling applied to the UK’s national HIV-diagnosis data of heterosexuals born abroad suggests an increasing trend. While in 2004 an estimated 24% had acquired HIV after migration in the UK, this rose to 46% in 2010 [4], which accounts for an absolute increase of 16.5%. Preliminary results of applying the same mathematical model to Belgium’s national HIV surveillance data suggested that among patients newly diagnosed in 2011, 28% (IQR 24%-33%) of non-Belgium born heterosexuals and 39% (IQR 32%-47%) of non-Belgium born MSM could have acquired HIV in Belgium [7]. The close-knit sexual networks of SAM [19], combined with structural vulnerability related to the migration context [20,21], may contribute to an increased risk for HIV infection among SAM residing in Belgium.

Knowledge Gaps for Effective HIV Prevention

HIV prevention comprises the continuum of primary prevention, promotion of HIV testing and counselling, and “positive health, dignity, and prevention,” which includes the prevention of HIV transmission. Yet, in Belgium [22] and its neighboring countries [23], prevention at the community level in the last decade focused mainly on the promotion of HIV testing and early linkage to care. Deeper understanding of SAM’s increased risk of being diagnosed late and the barriers to and facilitators of HIV-testing uptake [2,24-26] led to the development of multiple HIV-testing promotion strategies [14-16].

The prevention of new HIV infections, or primary prevention, among SAM has not been made priority because traditionally the HIV epidemic in the African diaspora in Europe was understood to be imported [27]. Evidence of SAM acquiring HIV after migration highlighted the need for tailored primary prevention interventions [4,5]. However, a number of gaps in in-depth understanding of transmission dynamics still exist. First, HIV prevalence estimates for a representative sample of the SAM communities in Europe are lacking, complicating HIV risk assessment and awareness raising in the communities. SAM have mostly formed subgroups in studies on HIV prevalence among other target groups, such as immigrant female sex workers [28], MSM [29], recently arrived migrants [6], and immigrants [30-34]. Only the MAYISHA II study, conducted in 2004 among 1359 black Africans in London, Luton, and the West-Midlands, provided HIV prevalence estimates of 14% [35]. Using a convenience sample of recruitment sites, this study did not include a representative sample, and subsequently, oversampling of HIV-positive individuals could not be excluded [4,5].

Second, estimates of the proportions of SAM with undiagnosed HIV are lacking. In Europe, one third of persons living with HIV are assumed to be unaware of their HIV status [21]. Some of the above-mentioned HIV prevalence studies provided indications that this might be higher among SAM; for example, MAYISHA II found that 66% of study participants with a positive test result did not report their HIV status on the questionnaire [35].

Third, previous research mainly focused on SAM’s individual knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to sexuality and HIV-preventive behavior, thus underestimating the social, cultural, religious, and migration-related contexts that increase vulnerability with respect to HIV [36]. Studies from the UK and the Netherlands underlined SAM’s preference for the heterosexual, monogamous standard [35]; yet, high number of partners (lifetime [37] and past year [30,35]), concurrent relationships, and having sex when traveling to home countries [30,34,37] were frequently reported, especially among men. This increased individual sexual risk behavior was shown to be linked to higher rates of sexually transmitted infections among SAM [34,37-39]. Several studies showed that SAM’s condom use was relatively high in comparison with the West-European population, but low considering their potential risk [40]. Africans were reported to believe that risk could be avoided by carefully choosing their sexual partners [40], to believe that condoms were associated with infidelity and reduced sexual pleasure, and to perceive condoms as inappropriate for long-term relationships [39,41-43]. Although these studies were useful to identify individual sexual risk patterns, they paid little attention to diversity among subgroups [36] and contextual factors influencing sexual behavior, and thus may be of limited use to develop and implement effective campaigns aiming to reduce HIV infection risk [44,45].

SAM Communities in Antwerp City

Although small in numbers, SAM communities are characterized by a high degree of heterogeneity due to diverse ethnic and cultural backgrounds, migration patterns and residence statuses, educational and socioeconomic backgrounds, and religious beliefs [22,45]. Of the 175,000 SAM officially living in Belgium [46], about 17,400 (10%) reside in Antwerp city (according to data obtained from the City of Antwerp; email communication from 2012 May 23). These numbers include SAM who obtained Belgian nationality, second-generation Belgian-born children of SAM parents, registered migrants, and SAM whose residence procedure is pending. SAM of undocumented legal status are absent from these statistics. Almost half (47%) of SAM in Antwerp city originate from 3 countries: the Democratic Republic of the Congo (18.8%), Ghana (17.5%), and Nigeria (10.7%). Apart from these 3 main nationalities, 43 other nationalities are living in this area. In spite of their heterogeneity, SAM communities are fairly homogeneously organized. For many SAM, their nationality and/or ethnicity shape their social life. As new migrants, they depend on the social support of their compatriots to become settled [47]. As established migrants, they engage in social and cultural networks and use them to look for marriage and sex partners [30]. Although these ethnic networks can be described as tight, they are not ethnically segregated. Different ethnic groups mingle at commercial and social venues and events. To reach different communities with HIV prevention activities, partnerships with leaders (ie, of sociocultural or spiritual organizations and owners of commercial settings) are essential [48-50].

Many SAM live in socioeconomically vulnerable and legally unstable conditions. Together with prevalent HIV-related stigma and culturally grounded taboos on sexuality, this translates into little demand for HIV prevention [50,51] and increased risk for HIV acquisition [48].

Methods

Study Objectives

The TOGETHER study’s overall aim was to increase the communities’, researchers’, and policymakers’ in-depth understanding of the dynamics of the HIV epidemic among SAM, to improve primary prevention interventions. This translated into the following objectives:

To assess the HIV prevalence and proportion of undiagnosed HIV infections among SAM socializing in community settings in Antwerp city.

To identify individual, community-level, and structural risk factors for HIV infection among SAM.

To identify priority settings and groups for future primary HIV prevention interventions.

To increase community ownership, involvement, and mobilization for HIV prevention.

To develop policy recommendations to improve HIV prevention for the target group of SAM.

To assess the feasibility and acceptability of community-based participatory research on HIV prevalence in SAM communities and adopted research tools.

Overall Study Design

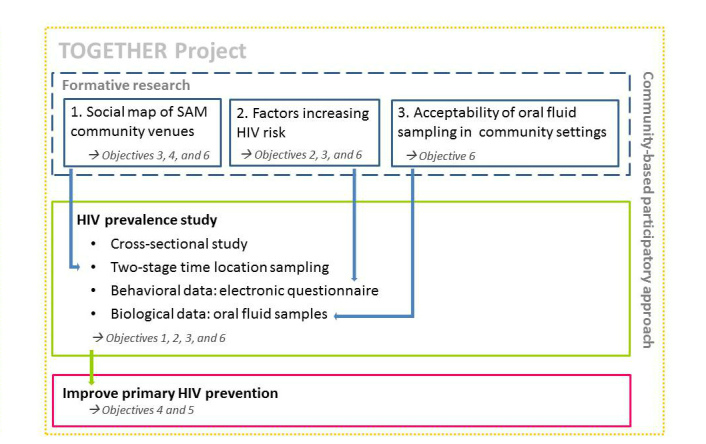

To meet these objectives, the TOGETHER Project applied mixed methods and a community-based participatory research approach (CBPR) [52]. The main study was a cross-sectional community-based bio-behavioral survey on HIV prevalence and HIV risk factors among SAM visiting community settings in Antwerp city (referred to as the “HIV prevalence study” in this article). To inform its design, 3 formative substudies were conducted. First, a social map of SAM community settings in Antwerp city was developed, applying an adaptation of the PLACE Method [53,54]. Second, factors that increase SAM’s risk of HIV infection were assessed using a multiple case study design. The third substudy assessed the acceptability and feasibility of using oral fluid collection devices for HIV testing in community venues through participatory observations, including informal interviews (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Outline of the TOGETHER project.

For the different study components, separate study protocols were developed and ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Institute of Tropical Medicine and the ethical committee of the University Hospital Antwerp.

Community-Based Participatory Approach

To account for the heterogeneity of Antwerp’s SAM and to ensure that the study methods and tools were acceptable for all subgroups (objective 6), we chose a community-based participatory approach [52]. This methodology also allows for increasing community ownership, involvement, and mobilization for HIV prevention (objective 4) throughout the research process. In practice, community members are involved in all steps of the project, from conceptualization, to data collection, to development of new interventions and policy recommendations. We established collaborative partnerships both with research experts and communities [55], by engaging a team of community researchers (CRs) and setting up a community advisory board (CAB). The CAB hosted both leaders of African organizations and a multidisciplinary group of professionals. The CRs were 9 lay community members, who were trained at the start of the project and continuously coached throughout. To reflect the communities’ diversity, the CR team was diverse in its composition with respect to gender, age, origin, residence status, employment status, and HIV status. In line with the Greater Involvement of People living with HIV/ AIDS (GIPA) principles [56], we actively recruited SAM living with HIV for the CRs team.

Formative Research

Formative Study 1: Social Mapping of Sub-Saharan African Community Venues in Antwerp City

This study ran from June 2012 until June 2013 and had the triple objective of (1) determining the sampling frame for the HIV prevalence study, (2) identifying priority settings for future HIV prevention, and (3) increasing communities’ ownership of HIV prevention.

To account for the heterogeneity of the SAM communities and ensure inclusion of hidden subpopulations, for example, SAM of undocumented status or MSM, we chose to employ the systematic approach of the PLACE Method (Prioritising Local AIDS Control Efforts) [53,54]. Guided by epidemiological theories, the PLACE Method has been widely used to monitor and improve AIDS prevention program coverage in areas where HIV transmission is most likely to occur, for example, by identifying venues where people meet sexual partners. It is a 5-step method adopted for surveillance studies, intervention design, programmatic up-scaling, and community mobilization [53,54,57-59]. We adapted the method to better meet our objectives by including steps 1 to 3, while replacing steps 4 and 5 with the HIV prevalence study (see below).

In step 1, “identifying a priority prevention area,” Antwerp city was selected based on demographic and epidemiological aspects: 22% of all SAM in Flanders live in Antwerp city [60] and, according to data available at the time, in 2010 43% of all newly diagnosed SAM in Flanders lived in Antwerp province. In step 2, “community informants” were interviewed, that is, adults who are knowledgeable about the community. Participants were asked where SAM socialize, and where they meet new sexual partners. We collected the locations of various publicly accessible meeting places such as bars, churches, shops, hair salons, asylum centers, a public library, parks, streets, squares, events, and festivities of African organizations. A convenience sample of community informants with different behavioral and sociodemographic characteristics, and of different professions, and community leaders of different origins, residing in different city districts, were interviewed to assure representativeness. After reaching saturation, duplications were removed from the compiled inventory of places and a consolidated list was generated. In step 3, all venues, areas, and events on the list were visited for a verification interview. Structured electronic questionnaires (SurveyToGo) were used to assess settings’ activities, characteristics of their visitors (origin, gender, etc.), busiest days and times, and existing HIV prevention programs, as well as to collect information on additional settings.

Formative Study 2: Assessing Factors that Increase Sub-Saharan African Migrants' Risk of HIV Infection: A Multiple Case Study

The second formative study contributed to the second overall project objective (ie, assessing individual, community-level, and structural risk factors). This study’s first phase took place between April 2013 and December 2013. The 3 specific objectives were: (1) informing the development of a structured questionnaire for the HIV prevalence study, (2) qualitatively contextualizing the findings of the HIV prevalence study, and (3) informing the development of future HIV prevention interventions. Study participants were SAM living with HIV, who were unique cases to retrospectively identify multi-level risk and vulnerability factors.

We conducted an empirical inquiry investigating a phenomenon within its real-life context, using multiple sources of evidence [61]. In our study, individual HIV positive SAM were the single object of a case. For each case, we triangulated findings from 3 data collection methods: life history interviews, timelines, and patient files. Per case, at least two life history interviews were conducted. Since chronology, sequencing of events, and context [62] are important to understand the setting in which HIV infection occurred, timelines were developed during these interviews. Timelines are visual depictions of an individual’s life events in chronological order that may include interpretations of these events [62]. We followed the timeline approach as described by Adrianson (2012), in which the drawing of the timeline is a collaborative effort shared by the interviewer and the interviewee, with the drawing forming the basis of the interview [63]. All interviews were conducted by a single interviewer (JL) who adopted an unstructured interview approach. This informal, open-ended, flexible, and free-flowing way of interviewing enabled participants to define the properties of the interview and direct the interview into areas that they saw as relevant [64]. The interview themes were the following: life story and events, migration (eg, pull and push factors, trajectory, immigration procedures), sexual and partner relationships, health-seeking behavior and coping styles and emotions (eg, effect of events on psychological well-being, coping with HIV, stigma and discrimination), social embeddedness (eg, social network, family structure and support, social exclusion) and livelihood (eg, financial situation, housing). When the natural flow of the first interview did not spontaneously generate sufficient data on these themes, a focused approach was taken in the second and eventual follow-up interviews. Data from the life history interviews were triangulated with data from the patient files. This reduced potential limitations of life history interviews (eg, subjective distortion), enriched the findings, and increased internal validity within the cases.

In the first study phase, a convenience sample of SAM living with HIV was recruited through physicians and nurses of the HIV clinic and facilitators of an HIV support group for SAM. To arrive at a representative sample of the patient population of sub-Saharan African origin, in the second phase, with a start date of April 2016, we switched to purposive sampling.

All participants in the first study phase were consenting adults who received their HIV diagnoses between 6 months and 10 years ago, who were assessed by health care providers as being psychologically stable and were followed up by a social nurse at the time of the interview. The latter was important to assure linkage to psychosocial care in case the interviews evoked emotional upheaval. The same rationale led to significant attention being paid to the informed consent procedure. Prior to the first interview, the study’s rationale, objectives, procedure, and confidentiality measures, and participants’ rights, benefits, and disadvantages were discussed extensively with the participant, before the informed consent form was signed. During this process, we asked for explicit approval to consult the participants’ patient files. For follow-up interviews, the procedure was repeated and verbal informed consent was obtained. As a token of appreciation, participants received an incentive of €25 for each interview.

To ensure participants’ anonymity and confidentiality, all data were coded and stored in a password-protected folder. All data were uploaded to NVivo 10 and a first within-case analysis was conducted. Data analysis adopted an inductive approach [65]. Triangulating the different data sources, the specific study questions were answered for each single case. Next, a cross-case analysis will be conducted at the end of the second study phase, to identify general factors that increase SAM’s vulnerability to HIV infection and facilitators of and barriers to behavior change.

Formative Study 3: Acceptability and Feasibility of Outreach HIV Testing Using Oral Fluid Collection Devices

For the HIV prevalence study, we opted for collecting oral fluid samples to determine HIV status, since reluctance toward blood taking is known to limit HIV testing uptake among SAM [66]. Although oral fluid collection devices had been used in comparable studies [30,35], none took place in Belgium; thus, their acceptability in SAM community settings was unknown. Therefore, an acceptability study was conducted between December 2012 and June 2013 within the framework of another HIV testing intervention named “swab2know.”

This intervention of the Institute of Tropical Medicine offered free oral fluid HIV tests (Oracol device, Malvern Medical Developments, Worcester, UK) in community settings of two target groups (MSM [67] and SAM) in Antwerp city. The HIV testing sessions for SAM were organized in collaboration with community leaders and included group counseling and testimony of an HIV-positive community member. If participants decided to test, they could choose to collect their result a week later via a secured website or face-to-face consultation at a low-threshold HIV testing center (ie, focusing on high-risk groups such as SAM). To assess the feasibility and acceptability of this intervention, including the specific sampling method for SAM, two social scientists (JL and FN) conducted participant observations [68] at 10 HIV testing sessions. Besides observation, informal interviews were conducted with testers, nontesters, and the intervention team. Field notes were coded using NVivo 10 using a data-driven code book and analyzed following inductive analysis principles [65].

Community-Based Survey on HIV Prevalence and HIV Risk Factors Among Sam Visiting Community Venues in Antwerp City

The primary objective of this cross-sectional study, which ran from December 2013 to August 2014, was to determine HIV prevalence among SAM socializing in community settings in Antwerp city (objective 1 of the TOGETHER Project). Secondary objectives were: (1) Identifying the individual, community-level, and structural risk factors for HIV infection among SAM; and (2) Identifying priority settings for future HIV prevention interventions (project objectives 2 and 3, respectively).

Sample Size

HIV prevalence was the primary outcome measure. The sample size was calculated using an anticipated HIV prevalence of 4%, a required precision of 2% for the 95% confidence intervals, and a cluster sampling design effect of 2. This resulted in a required sample size of 714 SAM.

Sampling Method

A 2-stage time location sampling (TLS) was adopted. TLS takes advantage of the fact that some hard-to-reach populations tend to gather or congregate at certain types of locations [69]. The list of settings established in formative study 1 was the sampling frame, from which a 2-stage cluster probability sample was selected. At the first level of sampling, 51 clusters, or sites, were randomly selected from the list with a probability proportional-to-size. When a selected site was not available (eg, refusal of the bar owner, closure of the site, site moved out of study area), this was noted and the next site on the list was approached. The second level of sampling included the random selection of 14 study participants from each cluster.

To be eligible, potential study participants had to self-identify as belonging to the SAM communities, be 18 years or older, agree to answer the behavioral questionnaire, donate an oral fluid sample, and be willing and able to provide written informed consent. Prior participation in the prevalence study was an exclusion criterion.

Measures

The study combined biological and behavioral measures. To measure the study’s primary outcome, HIV prevalence, oral fluid samples were collected and tested for HIV antibodies in the AIDS Reference Laboratory. These samples were linked through a unique code to an anonymous behavioral questionnaire. This instrument included questions on participants’ socio-demographic and economic background, migration and mobility background, health-seeking behavior, HIV-testing behavior, sexual and relational history (last year and lifetime), attitudes towards condom use, actual condom use, and level of assistance needed to complete the questionnaire. The structured electronic questionnaire was developed based on the findings of formative study 2, consultation of available questionnaires from comparable studies [39,42], and input from the CRs and CABs. It was refined after cognitive piloting with 12 participants and the pilot sessions (see below).

Data Collection Procedures

Detailed study procedures were described in the Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) developed in collaboration with the CRs, CAB, and the AIDS reference laboratory. The SOP were refined after 2 pilots. At pre-arranged moments, a study team visited the selected sites and randomly selected 14 of the SAM present. When approaching potential participants, the CRs identified themselves and introduced the study’s objectives and methodology, stressing the anonymous and voluntary nature of participation. To avoid self-exclusion of HIV-positive individuals, they explicitly mentioned that everybody was invited to participate, regardless of HIV status. Interested individuals were invited to a quiet area in the setting, if available. After discussing and signing the informed consent form, participants were asked to complete a structured anonymous electronic questionnaire on a tablet through SurveyToGo. To build confidence and ensure data rigor, participants first received a short tutorial on how to use the tablet. Here, special attention was given to the demonstration of how anonymity was guaranteed. Questionnaires were available in French, English, and Dutch, which are reference languages for most SAM. The preferred interview method was self-completion; however, assistance was offered if needed. By ethnically matching the CRs to the settings, translation of questions to a local language was possible, if preferred. The CRs were trained to offer assistance with sensitivity and respect to confidentiality.

After completing the questionnaire, the CR demonstrated the procedure of oral fluid collection using the collection device. Next, participants were asked to self-collect the sample. The sample was then linked with the informed consent form, questionnaire, and a letter explaining how to collect the results through a unique code (no personal identifying information was requested). If they wished, participants could collect their HIV test result by calling the study nurse and providing their unique code, age, and country of origin. When results turned out to be HIV positive, participants were invited to the HIV testing center for confirmation testing, counselling, and linkage to care.

Finally, participants were asked to provide information on their frequency of attending the study settings and comparable settings. This allowed the calculation of a weighting factor (see “data analysis”). As a token of appreciation, participants received free condoms, an information brochure on HIV testing, and €5. Those who refused participation received condoms and the information brochure, but no financial compensation. Data on their characteristics and reasons for refusal were also collected, as well as the overall number of individuals present during the onsite data collection.

Laboratory Procedures

Within 7 days of collecting the sample, the AIDS reference laboratory of the Institute of Tropical Medicine performed the analysis according to a validated algorithm using oral fluid specimens [70]. First, samples were tested with a Genscreen HIV ½ v2 (BioRad). If reactive, a second HIV ELISA test, Vironostika HIV Ag/Ab (BioMérieux) was performed. Only participants with 2 reactive test results were considered to be HIV-infected. For all negative samples, the quality of the oral fluid samples was measured using an IgG ELISA quantification kit (Human Total IgG ELISA, Immunology Consultants Laboratory, Inc, Cat No: E-80G). Samples were considered valid for analysis and results of the HIV test were only reported when sufficient IgG was present in the sample. All other samples were considered nonvalid and excluded from analysis.

Data Analysis

Data from the questionnaires, attendance forms, laboratory data (HIV status), and HIV test result collection form were linked via the unique code, merged, and stored in an SPSS Statistics 22 (IBM) database. After data cleaning, statistical analysis was carried out. An analysis plan to take into account cluster sampling and a weighting factor [71] was developed using IBM SPSS Complex Samples 22. SAM who visited sites more frequently had a higher probability of selection in the study. Adjustment for this unequal selection probability was completed by calculating individual weights, based on the attendance information provided by the participant as provided on the venue attendance form. The first step of the data analysis was a univariate descriptive analysis of all outcome variables, stratified by gender, including HIV prevalence. Categorical variables were summarized by proportions and 95% confidence intervals. Nonnormally distributed quantitative data were described by median and interquartile ranges. During a second step, bivariate analysis was conducted by exploring potential determinants of HIV infection and HIV-risk taking behavior. Odds ratios were calculated to measure the association and statistical significance testing was done using a chi-square or t test. A multivariate analysis still has to be performed, using a logistic regression model constructed with all variables independently associated with HIV infection, sexual risk behavior, condom use, and testing behavior.

Results

Results have been obtained from 4 interlinked studies and will be described in future research.

Discussion

The TOGETHER Project was conceptualized to respond to the growing need for investing in targeted primary prevention interventions to reduce new HIV infections among SAM. Increasing evidence indicates that more SAM than previously assumed acquire HIV after migration to West European host countries [4-8]; however, in-depth understanding of individual, community-level, and structural factors that increase risk and vulnerability for HIV are lacking. This hampers the development and implementation of tailored responses. Applying a mix of empirically tested and innovative epidemiological and social science methods through a CBPR approach could potentially reduce this knowledge gap, while increasing community ownership, investment, and mobilization for prevention. Against this background, the project’s objective was to generate the first HIV prevalence estimates for a representative sample of SAM residing in a Western European country and to yield an in-depth understanding of the multiple factors leading to HIV infection among SAM.

Our HIV prevalence study adopted methods successfully implemented in previous bio-behavioral surveys and cross-sectional studies [30,34,35,55], that is, combining anonymous biological data from oral fluid sampling with behavioral questionnaire data collected in community venues and public areas by ethnically matched volunteer interviewers. To obtain reliable HIV prevalence estimates representative of the diverse and heterogeneous SAM communities socializing in Antwerp city, we extended these methods with a 2-stage time location sampling approach. A limitation of the time location sampling is the difficulty in estimating the probability of missing an individual who never attends any of the venues listed. We adopted extensive formative research to develop an exhaustive social map of community settings covering all aspects of social life in order to limit that probability.

Study methods and tools were continuously refined based on the input of a CAB, CRs team, and the findings of two additional formative studies. To the best of our knowledge, this was the first time that such a carefully designed CBPR design had been adopted in Europe to assess HIV prevalence among a representative sample of SAM.

Due to practical limitations, the study setting was limited to Antwerp city. While Antwerp is the major city where SAM reside in Flanders, this implies that, although the HIV prevalence study will generate a sound estimation of HIV prevalence among SAM, the results cannot be generalized to Belgium or other West European countries. Different compositions of SAM communities in other cities have to be considered. For example, in Brussels 47% of SAM are of Congolese origin [46], while in the UK a vast majority come from Eastern and Southern Africa [72].

Adopting the CBPR approach as outlined is known to be challenging in terms of assuring skills of lay researchers, and safeguarding continuous motivation and data quality [52,73]. Our experience shows that the advantages outweighed these potential limitations. Adopting a CBPR approach improved access to hidden and hard-to-reach subpopulations, ensured acceptability of the study and its methods, built community ownership for HIV prevention, respected GIPA principles, and made the HIV epidemic real to individuals in the community, as was also shown by a comparable study among MSM in Antwerp city [74]. To generate this effect, we invested in sufficient training, individual coaching, and regular meetings with the CRs and set up rigorous data quality assurance measures throughout the entire research process.

Ability to ensure community mobilization for HIV prevention may be challenged by time constraints. While some subgroups are stable communities, others are known to evolve rapidly, community venues are often unstable, and leadership fluctuates [22]. Therefore, the projects’ results concerning priority places for prevention (objective 3) need constant follow-up (eg, to track where venues moved to, to assure contacts with new leaders).

With respect to the multiple-case study, it should be mentioned that our approach to identifying factors that increase SAM’s vulnerability to HIV infection was innovative (ie, triangulation of data from life history interviews, lifelines with patient files). In particular, the use of lifelines was, according to our literature search, new to HIV research. These qualitative insights were valuable in the analysis and contextualization of the HIV prevalence study’s findings. Together, they will form a solid basis for policy recommendations and the development of future HIV prevention interventions, once all study results are available.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the team of community researchers for their insights and continuous engagement: Sophiah Atieno, John Che Akangwa, Sandra Karorero, John Mugabi, Morgan Ndungu, Eveline Pilime, Electa Tamasang, Daniel Tantoh, and Jean Senga. Janvier Muhizi, the project’s study assistant is highly appreciated for his all-around support. We also acknowledge the members of the community advisory board for their input in the studies’ design: Laura Albers (Helpcenter-ITM), Rans Aubin (Ghana Welfare), Florent Batoum Bahiengraga (ACASIA vzw), Erika Delporte (ARC, ITM), Levis Kadia (Bilenge vzw), Tine Vermoesen (ARL, ITM), and Hans Willems (City of Antwerp). In addition, we wish to thank Dominique Van Beckhoven and Andre Sasse from WIV for their input on the epidemiological background. Veronica van Wijk and Sabien Salomez are thanked for their language editing and help with reference manager. Finally, we wish to thank the Scientific Fund for Research on AIDS, managed by the King Baudouin Foundation, for financially supporting the project.

Abbreviations

- CAB

community advisory board

- CBPR

community-based participatory research

- CRs

community researchers

- GIPA

greater involvement of people living with HIV/AIDS

- MSM

men having sex with men

- PLACE

Prioritising Local AIDS Control Efforts

- SAM

sub-Saharan African migrants

- TLS

time location sampling

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Wilson D, Halperin DT. "Know your epidemic, know your response": A useful approach, if we get it right. Lancet. 2008 Aug 9;372(9637):423–426. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60883-1.S0140-6736(08)60883-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, WHO Regional Office for Europe . HIV/AIDS Surveillance in Europe 2012. Stockholm: ECDC; 2013. [2015-09-24]. http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/hiv-aids-surveillance-report-Europe-2013.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sasse A, Deblonde J, Van Beckhoven D. Epidemiologie van AIDS en HIV Infectie in België. Toestand op 31 december 2013. Brussel: WIV-ISP; 2014. [2015-09-24]. https://www.wiv-isp.be/News/Documents/Rapport_HIV-AIDS_2013_Print_Press.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rice BD, Elford J, Yin Z, Delpech VC. A new method to assign country of HIV infection among heterosexuals born abroad and diagnosed with HIV. AIDS. 2012 Sep 24;26(15):1961–1966. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283578b80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burns FM, Arthur G, Johnson AM, Nazroo J, Fenton KA. United Kingdom acquisition of HIV infection in African residents in London: More than previously thought. AIDS. 2009 Jan 14;23(2):262–266. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831c546b.00002030-200901140-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saracino A, Scotto G, Tartaglia A, Fazio V, Cibelli DC, Di TR, Fornabaio C, Lipsi MR, Angarano G. Low prevalence of HIV infection among immigrants within two months of their arrival in Italy. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008 Sep;22(9):691–692. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rice B. Estimating probable place of HIV infection among persons born abroad. 3rd BREACH Symposium; Nov 21-22, 2014; Brussels, Belgium. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.European Centre for Disease Control . Migrant Health. Sexual Transmission of HIV Within Migrant Groups in the EU/EEA and Implications for Effective Interventions. Stockholm: ECDC; 2013. http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/Migrant-health-sexual-transmission.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 9.Health Protection Agency Centre for Infections . Longitudinal Analysis of the Trajectories of CD4 Cell Counts. London: Health Protection Agency Centre for Infections; 2008. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/331155/Longitudinal_analysis_of_the_trajectories_of_CD4_cell_count.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ndiaye B, Salleron J, Vincent A, Bataille P, Bonnevie F, Choisy P, Cochonat K, Fontier C, Guerroumi H, Vandercam B, Melliez H, Yazdanpanah Y. Factors associated with presentation to care with advanced HIV disease in Brussels and Northern France: 1997-2007. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-11. http://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2334-11-11 .1471-2334-11-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erwin J, Morgan M, Britten N, Gray K, Peters B. Pathways to HIV testing and care by black African and white patients in London. Sex Transm Infect. 2002 Feb;78(1):37–39. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.1.37. http://sti.bmj.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=11872857 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mocroft A, Lundgren JD, Sabin ML, Monforte AD, Brockmeyer N, Casabona J, Castagna A, Costagliola D, Dabis F, De Wit S, Fätkenheuer G, Furrer H, Johnson AM, Lazanas MK, Leport C, Moreno S, Obel N, Post FA, Reekie J, Reiss P, Sabin C, Skaletz-Rorowski A, Suarez-Lozano I, Torti C, Warszawski J, Zangerle R, Fabre-Colin C, Kjaer J, Chene G, Grarup J, Kirk O, Collaboration of Observational HIV Epidemiological Research Europe (COHERE) study in EuroCoord Risk factors and outcomes for late presentation for HIV-positive persons in Europe: Results from the Collaboration of Observational HIV Epidemiological Research Europe Study (COHERE) PLoS Med. 2013;10(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001510. http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001510 .PMEDICINE-D-13-00541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.May M, Gompels M, Delpech V, Porter K, Post F, Johnson M, Dunn D, Palfreeman A, Gilson R, Gazzard B, Hill T, Walsh J, Fisher M, Orkin C, Ainsworth J, Bansi L, Phillips A, Leen C, Nelson M, Anderson J, Sabin C. Impact of late diagnosis and treatment on life expectancy in people with HIV-1: UK Collaborative HIV Cohort (UK CHIC) Study. BMJ. 2011;343 doi: 10.1136/bmj.d6016. http://www.bmj.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=21990260 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamers FF, Phillips AN. Diagnosed and undiagnosed HIV-infected populations in Europe. HIV Med. 2008 Jul;9 Suppl 2:6–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00584.x.HIV584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krentz HB, Gill MJ. Cost of medical care for HIV-infected patients within a regional population from 1997 to 2006. HIV Med. 2008 Oct;9(9):721–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00613.x.HIV613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleishman JA, Yehia BR, Moore RD, Gebo KA. The economic burden of late entry into medical care for patients with HIV infection. Med Care. 2010 Dec;48(12):1071–1079. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181f81c4a. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/21063228 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall HI, Holtgrave DR, Maulsby C. HIV transmission rates from persons living with HIV who are aware and unaware of their infection. AIDS. 2012 Apr 24;26(7):893–896. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328351f73f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marks G, Crepaz N, Janssen RS. Estimating sexual transmission of HIV from persons aware and unaware that they are infected with the virus in the USA. AIDS. 2006 Jun 26;20(10):1447–1450. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000233579.79714.8d.00002030-200606260-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marsicano E, Lydié N, Bajos N. 'Migrants from over there' or 'racial minority here'? Sexual networks and prevention practices among sub-Saharan African migrants in France. Cult Health Sex. 2013;15(7):819–835. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2013.785024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alvarez-del Arco D, Monge S, Azcoaga A, Rio I, Hernando V, Gonzalez C, Alejos B, Caro AM, Perez-Cachafeiro S, Ramirez-Rubio O, Bolumar F, Noori T, Del Amo AJ. HIV testing and counselling for migrant populations living in high-income countries: A systematic review. Eur J Public Health. 2013 Dec;23(6):1039–1045. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cks130. http://eurpub.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=23002238 .cks130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . Migrant Health: Epidemiology of HIV and AIDS in Migrant Communities and Ethnic Minorities in EU/EEA Countries. Stockholm: ECDC; 2010. [2015-09-24]. http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/0907_TER_Migrant_health_HIV_Epidemiology_review.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 22.HIV-SAM Project . Vlaamse organisatie met terreinwerking voor seksuele gezondheid bij Subsaharaanse Afrikaanse migranten. Beleidsplan 2012-2016. Antwerp: Institute of Tropical Medicine; 2011. [2015-09-24]. http://www.zorg-en-gezondheid.be/uploadedFiles/NLsite_v2 /Zorgaanbod/Preventieve_gezondheidszorg/Organisaties_met_terreinwerking/11-4112%20BHO_OT_SAM_2012_beleidsplan2012-2016_revised.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ministère de la Santé et des Sports . Plan National de Lutte Contre le VIH/SIDA et les IST. 2010-2014. Paris: Ministère de la Santé et des Sports; 2010. [2015-09-24]. http://www.sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/plan_national_lutte_contre_le_VIH-SIDA_et_les_IST_2010-2014.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boyd AE, Murad S, O'shea S, de Ruiter A, Watson C, Easterbrook PJ. Ethnic differences in stage of presentation of adults newly diagnosed with HIV-1 infection in south London. HIV Med. 2005 Mar;6(2):59–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2005.00267.x.HIV267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burns FM, Fakoya AO, Copas AJ, French PD. Africans in London continue to present with advanced HIV disease in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2001 Dec 7;15(18):2453–2455. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200112070-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chee CC, Mortier E, Dupont C, Bloch M, Simonpoli AM, Rouveix E. Medical and social differences between French and migrant patients consulting for the first time for HIV infection. AIDS Care. 2005 May;17(4):516–520. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331291760.J280V42268122977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sinka K, Mortimer J, Evans B, Morgan D. Impact of the HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa on the pattern of HIV in the UK. AIDS. 2003 Jul 25;17(11):1683–1690. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000060392.18106.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Platt L, Grenfell P, Fletcher A, Sorhaindo A, Jolley E, Rhodes T, Bonell C. Systematic review examining differences in HIV, sexually transmitted infections and health-related harms between migrant and non-migrant female sex workers. Sex Transm Infect. 2013 Jun;89(4):311–319. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2012-050491.sextrans-2012-050491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dougan S, Elford J, Rice B, Brown AE, Sinka K, Evans BG, Gill ON, Fenton KA. Epidemiology of HIV among black and minority ethnic men who have sex with men in England and Wales. Sex Transm Infect. 2005 Aug;81(4):345–350. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.012328. http://sti.bmj.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=16061545 .81/4/345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gras MJ, Weide JF, Langendam MW, Coutinho RA, van den Hoek A HIV prevalence, sexual risk behaviour and sexual mixing patterns among migrants in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. AIDS. 1999 Oct 1;13(14):1953–1962. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199910010-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monge-Maillo B, Jiménez BC, Pérez-Molina JA, Norman F, Navarro M, Pérez-Ayala A, Herrero JM, Zamarrón P, López-Vélez R. Imported infectious diseases in mobile populations, Spain. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009 Nov;15(11):1745–1752. doi: 10.3201/eid1511.090718. doi: 10.3201/eid1511.090718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pérez-Molina JA, López-Vélez R, Navarro M, Pérez-Elías MJ, Moreno S. Clinicoepidemiological characteristics of HIV-infected immigrants attended at a tropical medicine referral unit. J Travel Med. 2009;16(4):248–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2009.00308.x.JTM308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stolte IG, Gras M, Van Benthem BHB. Coutinho RA, van den Hoek JAR HIV testing behaviour among heterosexual migrants in Amsterdam. AIDS Care. 2003 Aug;15(4):563–574. doi: 10.1080/0954012031000134791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Veen MG, Schaalma H, van Leeuwen AP, Prins M, de Zwart O, van de Laar MJW, Hospers HJ. Concurrent partnerships and sexual risk taking among African and Caribbean migrant populations in the Netherlands. Int J STD AIDS. 2011 May;22(5):245–250. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2009.008511.22/5/245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sadler KE, McGarrigle CA, Elam G, Ssanyu-Sseruma W, Davidson O, Nichols T, Mercey D, Parry JV, Fenton KA. Sexual behaviour and HIV infection in black-Africans in England: Results from the Mayisha II survey of sexual attitudes and lifestyles. Sex Transm Infect. 2007 Dec;83(7):523–529. doi: 10.1136/sti.2007.027128. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/17932129 .sti.2007.027128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prost A, Sseruma WS, Fakoya I, Arthur G, Taegtmeyer M, Njeri A, Fakoya A, Imrie J. HIV voluntary counselling and testing for African communities in London: Learning from experiences in Kenya. Sex Transm Infect. 2007 Dec;83(7):547–551. doi: 10.1136/sti.2007.027110. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/17911136 .sti.2007.027110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fenton KA, Mercer CH, McManus S, Erens B, Wellings K, Macdowall W, Byron CL, Copas AJ, Nanchahal K, Field J, Johnson AM. Ethnic variations in sexual behaviour in Great Britain and risk of sexually transmitted infections: A probability survey. Lancet. 2005;365(9466):1246–1255. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74813-3.S0140-6736(05)74813-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gras MJ, van Benthem BHB. Coutinho RA, van den Hoek A Determinants of high-risk sexual behavior among immigrant groups in Amsterdam: Implications for interventions. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001 Oct 1;28(2):166–172. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200110010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.MAYISHA II Collaborative Group . Mayisha II Main Study Report. Assessing the Feasibility and Acceptability of Community Based Prevalence Surveys of HIV Among Black Africans in England. London: Health Protection Agency; 2005. [2016-03-03]. http://kwp.org.uk/files/mayisha_11_2005.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prost A, Elford J, Imrie J, Petticrew M, Hart GJ. Social, behavioural, and intervention research among people of Sub-Saharan African origin living with HIV in the UK and Europe: Literature review and recommendations for intervention. AIDS Behav. 2008 Mar;12(2):170–194. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9237-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elam G. Exploring Ethnicity and Sexual Health: A Qualitative Study of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles of Five Ethnic Minority Communities in Camden and Islington. London: University College London; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manirankunda L, Alou T, Kint I, Ronkes C, De Reuwe E, Struelens R, Lafont Y, Buvé A, Laga M. Evaluation des Comportements a Risque à la Transmission des MST/VIH Dans la Population Immigrante Originaire d'Afrique Subsaharienne Residant Dans la Ville d'Anvers. Antwerp: Institute of Tropical Medicine; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wiggers LCW, de Wit JBF, Gras MJ, Coutinho RA, van den Hoek A. Risk behavior and social-cognitive determinants of condom use among ethnic minority communities in Amsterdam. AIDS Educ Prev. 2003 Oct;15(5):430–447. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.6.430.24042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barrett HR, Mulugeta B. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and migrant "risk environments": The case of the Ethiopian and Eritrean immigrant community in the West Midlands of the UK. Psychol Health Med. 2010 May;15(3):357–369. doi: 10.1080/13548501003653192.922291193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kesby M, Fenton K, Boyle P, Power R. An agenda for future research on HIV and sexual behaviour among African migrant communities in the UK. Soc Sci Med. 2003 Nov;57(9):1573–1592. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00551-8.S0277953602005518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.FOD Economie KMO, Middenstand en Economie Bevolking op 1 januari: Bevolking naar nationaliteit, geslacht. Totale, vreemde en Belgische bevolking. http://economie.fgov.be/nl/modules/publications/statistiques/bevolking/downloads/bevolking_naar_nationaliteit_en_geslacht.jsp .

- 47.van Meeteren M, Engbersen G, van San M. Striving for a better position: Aspirations and the role of cultural, economic, and social capital for irregular migrants in Belgium. International Migration Review. 2009;43:881–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2009.00788.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Federal Public Service Health, Food Chain Security and Environment National HIV Plan Belgium 2014-2019. 2013. http://www.breach-hiv.be/media/docs/HIVPlan/NationalPlanDutch.pdf .

- 49.HIV-SAM Project . Vrijwillig HIV-Testen en Counselen (VCT) in Afrikaanse Gemeenschapssettings. Project Report. Antwerp: ITM; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pulle S, Lubege J, Davidson O, Chinouya M. Doing it Well. A Good Practice Guide for Choosing and Implementing Community-Based HIV prevention. London: African HIV Policy Network; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Manirankunda L, Loos J, Alou TA, Colebunders R, Nöstlinger C. "It's better not to know": Perceived barriers to HIV voluntary counseling and testing among sub-Saharan African migrants in Belgium. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009 Dec;21(6):582–593. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.6.582.10.1521/aeap.2009.21.6.582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Minkler M. Community-based research partnerships: Challenges and opportunities. J Urban Health. 2005 Jun;82(2 Suppl 2):ii3–12. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti034. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/15888635 .jti034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.MEASURE Evaluation Project . Priorities for Local AIDS Control Efforts. A Manual for Implementing the PLACE Method. Chapel Hill: Measure Evaluation, University of North Carolina; 2005. [2015-09-24]. http://www.cpc.unc.edu/measure/publications/ms-05-13 . [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weir SS, Pailman C, Mahlalela X, Coetzee N, Meidany F, Boerma JT. From people to places: Focusing AIDS prevention efforts where it matters most. AIDS. 2003 Apr 11;17(6):895–903. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000050809.06065.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sadler KE, McGarrigle CA, Elam G, Ssanyu-Sseruma W, Othieno G, Davidson O, Mercey D, Parry JV, Fenton KA. Mayisha II: Pilot of a community-based survey of sexual attitudes and lifestyles and anonymous HIV testing within African communities in London. AIDS Care. 2006 May;18(4):398–403. doi: 10.1080/09540120600634400.R6L301212HX81Q37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.UNAIDS . From principle to practice: Greater involvement of people living with or affected by HIV/AIDS (GIPA) Geneva: UNAIDS; 1999. [2015-09-24]. http://data.unaids.org/Publications/IRC-pub01/JC252-GIPA-i_en.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 57.Singh K, Sambisa W, Munyati S, Chandiwana B, Chingono A, Monash R, Weir S. Targeting HIV interventions for adolescent girls and young women in Southern Africa: Use of the PLACE methodology in Hwange District, Zimbabwe. AIDS Behav. 2010 Feb;14(1):200–208. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9572-8. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/19452272 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tate J, Singh K, Ndubani P, Kamwanga J, Buckner B. Measurement of HIV prevention indicators: A comparison of the PLACE method and a household survey in Zambia. AIDS Behav. 2010 Feb;14(1):209–217. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9505-y. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/19089607 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wohl DA, Khan MR, Tisdale C, Norcott K, Duncan J, Kaplan AM, Weir SS. Locating the places people meet new sexual partners in a southern US city to inform HIV/STI prevention and testing efforts. AIDS Behav. 2011 Feb;15(2):283–291. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9746-4. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/20614175 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Statistics Belgium . Structure of the Population According to Country of Birth, 2012. Brussels: FOD Economie; http://economie.fgov.be/nl/statistieken/cijfers/bevolking/structuur/geboorteland . [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yin RK. Case Study Research. Design and Methods. Newbury Pary, CA: Sage; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gramling LF, Carr RL. Lifelines: A life history methodology. Nurs Res. 2004;53(3):207–210. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200405000-00008.00006199-200405000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Adriansen HK. Timeline interview: A tool for conducting life history research. Qual Stud. 2012;3(1):40–55. [Google Scholar]

- 64.May T. Social Research. Issues, Methods and Process. 4th edition. Glasglow: Open University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Patton M. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3rd edition. London: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Navaza B, Guionnet A, Navarro M, Estévez L, Pérez-Molina JA, López-Vélez R. Reluctance to do blood testing limits HIV diagnosis and appropriate health care of sub-Saharan African migrants living in Spain. AIDS Behav. 2012 Jan;16(1):30–35. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9871-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Platteau T, Fransen K, Apers L, Kenyon C, Albers L, Vermoesen T, Loos J, Florence E. Swab2know: An HIV-testing strategy using oral fluid samples and online communication of test results for men who have sex with men in Belgium. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(9):e213. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4384. http://www.jmir.org/2015/9/e213/ v17i9e213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.De Walt KM, De Walt BR. Participant Observation: A Guide for Fieldworkers. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Magnani R, Sabin K, Saidel T, Heckathorn D. Review of sampling hard-to-reach and hidden populations for HIV surveillance. AIDS. 2005 May;19 Suppl 2:S67–72. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000172879.20628.e1.00002030-200505002-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fransen K, Vermoesen T, Beelaert G, Menten J, Hutse V, Wouters K, Platteau T, Florence E. Using conventional HIV tests on oral fluid. J Virol Methods. 2013 Dec;194(1-2):46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2013.08.004.S0166-0934(13)00336-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Karon JM, Wejnert C. Statistical methods for the analysis of time-location sampling data. J Urban Health. 2012 Jun;89(3):565–586. doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9676-8. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/22421885 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.National AIDS Trust . HIV and Black African Communities in the UK. A Policy Report. London: National AIDS Trust; 2014. http://www.nat.org.uk/media/Files/Publications/NAT-African-Communities-Report-June-2014-FINAL.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 73.Logie C, James L, Tharao W, Loutfy MR. Opportunities, ethical challenges, and lessons learned from working with peer research assistants in a multi-method HIV community-based research study in Ontario, Canada. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2012 Oct;7(4):10–19. doi: 10.1525/jer.2012.7.4.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vanden Berghe W, Nöstlinger C, Hospers H, Laga M. International mobility, sexual behaviour and HIV-related characteristics of men who have sex with men residing in Belgium. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:968. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-968. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/13/968 .1471-2458-13-968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dooblo Survey Software. Kfar Sava, Israel: Dooblo Ltd; 2011. [2016-02-16]. http://www.dooblo.net/ [Google Scholar]