Abstract

Summary: Mutational signatures are patterns in the occurrence of somatic single-nucleotide variants that can reflect underlying mutational processes. The SomaticSignatures package provides flexible, interoperable and easy-to-use tools that identify such signatures in cancer sequencing data. It facilitates large-scale, cross-dataset estimation of mutational signatures, implements existing methods for pattern decomposition, supports extension through user-defined approaches and integrates with existing Bioconductor workflows.

Availability and implementation: The R package SomaticSignatures is available as part of the Bioconductor project. Its documentation provides additional details on the methods and demonstrates applications to biological datasets.

Contact: julian.gehring@embl.de, whuber@embl.de

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 Introduction

Mutational signatures link observed somatic single-nucleotide variants to mutation generating processes (Alexandrov et al., 2013a). The identification of these signatures offers insights into the evolution, heterogeneity and developmental mechanisms of cancer (Fischer et al., 2013; Alexandrov et al., 2013b; Nik-Zainal et al., 2012). Existing softwares offer specialized functionality for this approach and have contributed to the characterization of signatures in multiple cancer types (Nik-Zainal et al., 2012; Fischer et al., 2013), while their reliance on custom data input and output formats limits integration into common workflows.

The SomaticSignatures package aims to encourage wider adoption of mutational signatures in tumor genome analysis by providing an accessible R implementation that supports multiple statistical approaches, scales to large datasets and closely interacts with the data structures and tools of Bioconductor (R Core Team, 2015; Gentleman et al., 2004).

2 Approach

The probability of a somatic single-nucleotide variant (SNV) to occur can depend on the sequence neighborhood, and a fruitful approach is to analyze SNV frequencies together with their immediate sequence context, the flanking 3 and 5 bases (Alexandrov et al., 2013b). As an example, the mutation of A to G in the sequence TAC defines the mutational motif T[A>G]C. The occurrence patterns of such motifs capture characteristics of mutational mechanisms, and the frequencies of the 96 possible motifs across all samples define the mutational spectrum. It is represented by the matrix M, with Mij enumerating over the motifs i and the samples j. The mutational spectrum can be interpreted by decomposing M into two matrices of smaller size (Nik-Zainal et al., 2012),

| (1) |

where the number of signatures r is typically small compared to the number of samples, and the elements of the residual matrix ε are minimized such that WH is a useful approximation of the data. The columns of W describe the composition of a signature: Wik is the relative frequency of somatic motif i in the kth signature. The rows of H indicate the contribution of each signature to a particular sample j. A primary goal of the SomaticSignatures package is the easy application of this approach to datasets in an environment that provides users with powerful visualizations and algorithms.

3 Methods

Several approaches exist for the decomposition [Equation (1)] that differ in their constraints and computational complexity. In principal component analysis (PCA), for a given r, W and H are chosen such that the norm is minimal and W is orthonormal. Non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) (Brunet et al., 2004) is motivated by the fact that the mutational spectrum fulfills and imposes the same requirement on the elements of W and H. Different NMF and PCA algorithms allow additional constraints on the results, such as sparsity. To deduce the number r of signatures present in the data, information theoretical criteria as well as prior biological knowledge can be employed (Nik-Zainal et al., 2012; Alexandrov et al., 2013a).

4 Results

SomaticSignatures is a flexible and efficient tool for inferring characteristics of mutational mechanisms, based on the methodology developed by Nik-Zainal et al. (2012). It integrates with Bioconductor tools for processing and annotating genomic variants. An analysis starts with a set of SNV calls, typically imported from a VCF file and represented as a VRanges object (Obenchain et al., 2014). Since the original calls do not contain information about the sequence context, we construct the mutational motifs first, based on the sequence of a reference or personalized genome.

Subsequently, we define the mutational spectrum M. While its columns are by default defined by the sample labels, users can specify an alternative grouping covariate, for example tumor type.

Mutational signatures and their contribution to each sample’s mutational spectrum are estimated with a chosen decomposition method for a defined number of signatures. We provide convenient access to implementations for NMF and PCA, and users can apply functions with alternative decomposition methods through the API.

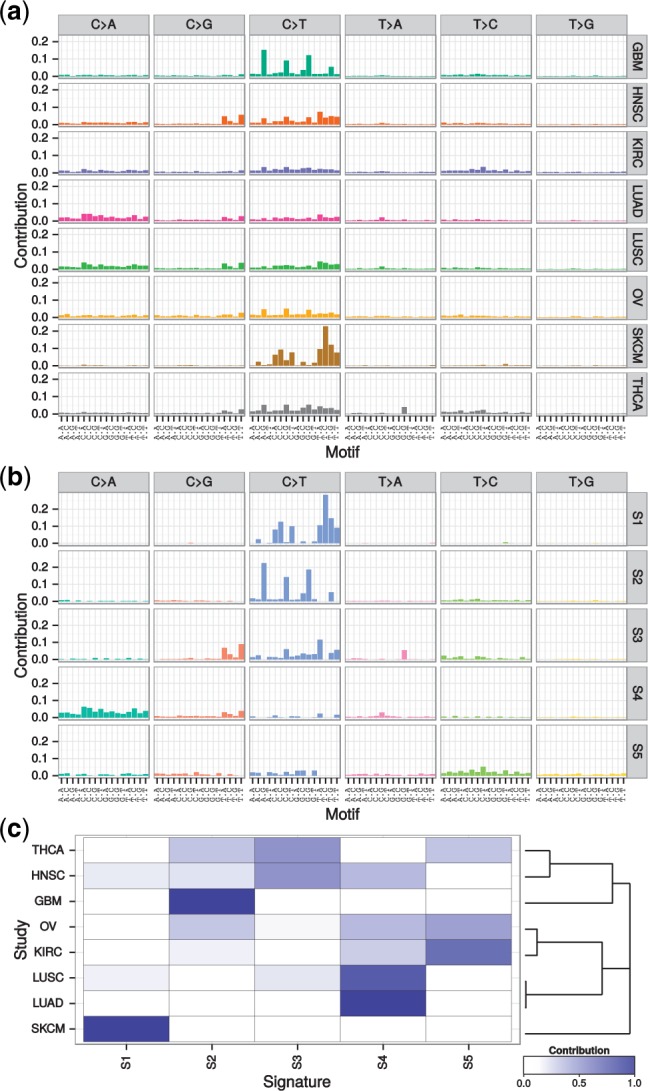

The user interface and library of plotting functions facilitate subsequent analysis and presentation of results (Fig. 1). Accounting for technical biases is often essential, particularly when analyzing across multiple datasets. For this purpose, we provide methods to normalize for the background distribution of sequence motifs and demonstrate the adjustment for batch effects.

Fig. 1.

Analysis of mutational signatures for eight TCGA studies (Gehring, 2014). The observed mutational spectrum of each study (panel a) was decomposed into five distinct mutational signatures S1–S5 (panel b) with NMF. The presence of these signatures in the studies (panel c), as shown by hierarchical clustering, underlines the similarities in mutational processes of biologically related cancer types. An annotated high-resolution version of this figure is available as Supplementary Figure S1

In the documentation of the software, we illustrate a use case by analyzing 594 607 somatic SNV calls from 2408 TCGA whole-exome sequenced samples (Gehring, 2014). The analysis, including NMF, PCA and hierarchical clustering, completes within minutes on a standard desktop computer. The different approaches yield a biologically meaningful grouping of the eight cancer types according to the estimated signatures (Fig. 1).

We have applied this approach to the characterization of kidney cancer and have shown that classification of subtypes according to mutational signatures is consistent with classification based on RNA expression profiling and mutation rates (Durinck et al., 2015).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We thank Leonard Goldstein and Oleg Mayba at Genentech Inc. for their insights and suggestions.

Footnotes

A version of btv408 has been published to include the PDF article and missing figures from the original article.

Funding

This work was supported by the NSF award 1247813 and Genentech Inc.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

References

- Alexandrov L.B., et al. (2013a) Deciphering signatures of mutational processes operative in human cancer. Cell Rep., 3, 246–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrov L.B., et al. (2013b) Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature, 500, 415–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet J.P., et al. (2004) Metagenes and molecular pattern discovery using matrix factorization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA., 101, 4164–4169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durinck S., et al. (2015) Spectrum of diverse genomic alterations define non-clear cell renal carcinoma subtypes. Nat. Genet., 47, 13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer A., et al. (2013) EMu: probabilistic inference of mutational processes and their localization in the cancer genome. Genome Biol., 14, R39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring J.S. (2014) SomaticCancerAlterations. Bioconductor package, version: 1.1.0. http://bioconductor.org/packages/SomaticCancerAlterations/ [Google Scholar]

- Gentleman R.C., et al. (2004) Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol., 5, R80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nik-Zainal S., et al. (2012) Mutational processes molding the genomes of 21 breast cancers. Cell, 149, 979–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obenchain V., et al. (2014) VariantAnnotation: a bioconductor package for exploration and annotation of genetic variants. Bioinformatics, 30, 2076–2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2015) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.