Abstract

The Ate1 arginyltransferase (R-transferase) is a component of the N-end rule pathway, which recognizes proteins containing N-terminal degradation signals called N-degrons, polyubiquitylates these proteins, and thereby causes their degradation by the proteasome. Ate1 arginylates N-terminal Asp, Glu, or (oxidized) Cys. The resulting N-terminal Arg is recognized by ubiquitin ligases of the N-end rule pathway. In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the separase-mediated cleavage of the Scc1/Rad21/Mcd1 cohesin subunit generates a C-terminal fragment that bears N-terminal Arg and is destroyed by the N-end rule pathway without a requirement for arginylation. In contrast, the separase-mediated cleavage of Rec8, the mammalian meiotic cohesin subunit, yields a fragment bearing N-terminal Glu, a substrate of the Ate1 R-transferase. Here we constructed and used a germ cell-confined Ate1−/− mouse strain to analyze the separase-generated C-terminal fragment of Rec8. We show that this fragment is a short-lived N-end rule substrate, that its degradation requires N-terminal arginylation, and that male Ate1−/− mice are nearly infertile, due to massive apoptotic death of Ate1−/− spermatocytes during the metaphase of meiosis I. These effects of Ate1 ablation are inferred to be caused, at least in part, by the failure to destroy the C-terminal fragment of Rec8 in the absence of N-terminal arginylation.

Keywords: meiosis, protein degradation, proteolysis, spermatogenesis, ubiquitin

Introduction

The N-end rule pathway is a set of proteolytic systems whose unifying feature is the ability to recognize and polyubiquitylate proteins containing degradation signals called N-degrons,6 thereby causing degradation of these proteins by the proteasome (Fig. 1, A and B) (1–8). The main determinant of an N-degron is either an unmodified or chemically modified destabilizing N-terminal residue of a protein. The identity of the next residue, at position 2, is often important as well. A second determinant of an N-degron is a protein's internal Lys residue. It functions as the site of a protein's polyubiquitylation and tends to be located in a conformationally disordered region (4, 9, 10). Recognition components of the N-end rule pathway are called N-recognins. In eukaryotes, N-recognins are E3 ubiquitin (Ub) ligases that can target N-degrons (Fig. 1, A and B). Bacteria also contain the N-end rule pathway, but Ub-independent versions of it (11–16).

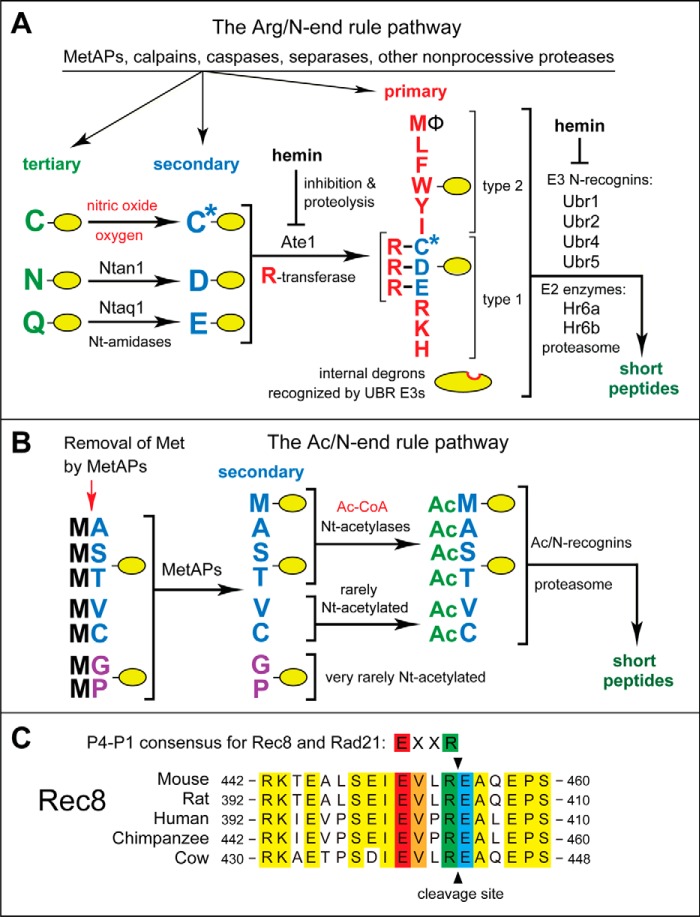

FIGURE 1.

The mammalian N-end rule pathway and the separase cleavage site in Rec8, a meiosis-specific cohesin subunit. See the Introduction for descriptions of the pathway's mechanistic aspects and biological functions. Amino acid residues are denoted by single-letter abbreviations. A, the Arg/N-end rule pathway. It targets proteins for degradation through their specific unacetylated N-terminal residues. A yellow oval denotes the rest of a protein substrate. R-transferase, Ate1 arginyltransferase; primary, secondary, and tertiary, mechanistically distinct classes of destabilizing N-terminal residues; type 1 and type 2, two sets of primary destabilizing N-terminal residues, basic (Arg, Lys, and His) and bulky hydrophobic (Leu, Phe, Trp, Tyr, Ile, and Met followed by a bulky hydrophobic residue (Φ)), respectively. These sets of N-terminal residues are recognized by two distinct substrate-binding sites of N-recognins, the pathway's E3 ubiquitin ligases. B, the Ac/N-end rule pathway. It targets proteins through their Nt-acetylated residues. The red arrow on the left indicates the cotranslational removal of the N-terminal Met residue by Met-aminopeptidases (MetAPs). N-terminal Met is retained if a residue at position 2 is larger than Val. C, alignments of amino acid sequences near the main separase cleavage site in mammalian Rec8, between Arg454 and Glu455 of mouse Rec8. The consensus sequence of this cleavage site (its P4–P1 residues) in both mitotic (Rad21) and meiotic (Rec8) kleisin-type cohesin subunits is also shown. Conserved residues of mammalian Rec8 near the cleavage site are shown in yellow. The conserved P4, P3, P1, and P1′ residues of mammalian Rec8 at the cleavage site are in red, orange, green, and blue, respectively.

Regulated degradation of proteins and their natural fragments by the N-end rule pathway has been shown to mediate a strikingly broad range of biological functions, including the sensing of heme, nitric oxide (NO), oxygen, and short peptides; the control, through subunit-selective degradation, of the input stoichiometries of subunits in oligomeric protein complexes; the elimination of misfolded or otherwise abnormal proteins; the degradation of specific proteins after their retrotranslocation to the cytosol from mitochondria or other membrane-enclosed compartments; the regulation of apoptosis and repression of neurodegeneration; the regulation of DNA repair, transcription, replication, and chromosome cohesion/segregation; the regulation of G proteins, autophagy, peptide import, meiosis, immunity, fat metabolism, cell migration, actin filaments, cardiovascular development, spermatogenesis, and neurogenesis; the functioning of adult organs, including the brain, muscle, testis, and pancreas; and the regulation of leaf and shoot development, leaf senescence, and many other processes in plants (Fig. 1, A and B) (see Refs. 4–7 and references therein).

In eukaryotes, the N-end rule pathway consists of two branches. One branch, called the Ac/N-end rule pathway, targets proteins for degradation through their Nα-terminally acetylated (Nt-acetylated) residues (Fig. 1B) (2, 3, 17–19). Degradation signals and E3 Ub ligases of the Ac/N-end rule pathway are called Ac/N-degrons and Ac/N-recognins, respectively. Nt-acetylation of cellular proteins is apparently irreversible, in contrast to acetylation-deacetylation of proteins' internal Lys residues. About 90% of human proteins are cotranslationally Nt-acetylated by ribosome-associated Nt-acetylases (20). Posttranslational Nt-acetylation is known to occur as well. Many, possibly most, Nt-acetylated proteins contain Ac/N-degrons (Fig. 1B).

The pathway's other branch, called the Arg/N-end rule pathway, targets specific unacetylated N-terminal residues (Fig. 1A) (3, 21–25). The “primary” destabilizing N-terminal residues Arg, Lys, His, Leu, Phe, Tyr, Trp, and Ile are directly recognized by N-recognins. The unacetylated N-terminal Met, if it is followed by a bulky hydrophobic (Φ) residue, also acts as a primary destabilizing residue (Fig. 1A) (3). In contrast, the unacetylated N-terminal Asn, Gln, Asp, and Glu (as well as Cys, under some metabolic conditions) are destabilizing due to their preliminary enzymatic modifications, which include Nt-deamidation of Asn and Gln and Nt-arginylation of Asp, Glu, and oxidized Cys (Fig. 1A) (4–6, 26). In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the Arg/N-end rule pathway is mediated by the Ubr1 N-recognin, a 225-kDa RING-type E3 Ub ligase and a part of the targeting complex comprising the Ubr1-Rad6 and Ufd4-Ubc4/5 E2-E3 holoenzymes (4, 27). In multicellular eukaryotes, several E3 Ub ligases, including Ubr1, function as N-recognins of the Arg/N-end rule pathway (Fig. 1A).

Nt-arginylation is mediated by the Ate1-encoded arginyltransferase (Arg-tRNA-protein transferase; R-transferase), a component of the Arg/N-end rule pathway and one subject of the present study (Fig. 1A) (28–36). Alternative splicing of mouse Ate1 pre-mRNAs yields at least six R-transferase isoforms, which differ in their Nt-arginylation activity (28, 31). R-transferases are sequelogous (similar in sequence (37)) throughout most of their ∼60-kDa spans from fungi to mammals (4). R-transferase can arginylate not only N-terminal Asp and Glu but also N-terminal Cys, if it has been oxidized to Cys-sulfinate or Cys-sulfonate, through reactions mediated by NO, oxygen, and N-terminal Cys-oxidases (5, 6, 30). Consequently, the Arg/N-end rule pathway functions as a sensor of NO and oxygen, through the conditional oxidation of N-terminal Cys in proteins such as the Rgs4, Rgs5, and Rgs16 regulators of G proteins in mammals (30, 38) and specific transcriptional regulators in plants (reviewed in Refs. 5 and 6). By now, more than 200 distinct proteins (including natural protein fragments) have been either shown or predicted to be Nt-arginylated (21, 22, 39–41). Many, possibly most, Nt-arginylated proteins are conditionally or constitutively short-lived substrates of the Arg/N-end rule pathway (Fig. 1A).

Identified and predicted substrates of the Arg/N-end rule pathway include cohesin subunits of the kleisin family. Rings of oligomeric cohesin keep sister chromatids together through a topological confinement (42–53). Physiological roles of cohesins include DNA replication, cohesion/segregation, repair, transcription, and control of apoptosis (54–61). In S. cerevisiae, the Scc1/Rad21/Mcd1 cohesin subunit is cleaved at a specific site, late in mitosis, by the nonprocessive Esp1 protease called separase, allowing the release of sister chromatids and the transition from metaphase to anaphase (48, 62–64).

In mammals and other multicellular eukaryotes, the bulk of cohesin-mediated confinement of sister chromatids is removed during prophase through openings of cohesin rings that do not involve proteolytic cuts. Sister chromatids continue to be held together until the end of metaphase, to a large extent through still intact cohesin rings at the centromeres. Once the bipolar spindle attachment of chromosomes is achieved at the end of metaphase, the activated separase cleaves the mammalian Rad21 subunit (a sequelog of yeast Scc1) in the closed cohesin complexes, resulting in their opening and allowing the separation of sister chromatids (45, 48, 58, 65). At least in mammals, the Rad21 cohesin subunit can be cleaved in vivo not only by separase but also by calpain-1 (a Ca2+-activated protease) (58) and by caspases as well (56, 57).

During meiosis, in which cohesins also play essential roles, the mitosis-specific cohesin subunit Rad21 is replaced by the sequelogous (similar in sequence (37)), meiosis-specific Rec8 subunit (43, 59, 66–70). (A second meiosis-specific kleisin-type subunit, called Rad21L, is expressed during early meiosis and disappears afterward (71).) Meiotic DNA replication is followed by two rounds of cell division to produce four haploid daughter cells. During the first meiotic cell division cycle (meiosis I), replicated homologous chromosomes pair and recombine with each other. The pairs of modified (recombined) homologous chromosomes are separated at the end of meiosis I, yielding two diploid daughter cells (72, 73). During meiosis II, the replicated sister chromatids of each chromosome are pulled apart to produce haploid daughter cells. In the testis of male mice, meiosis I and II take place in meiotic spermatocytes, leading to the formation of haploid spermatids and later mature sperm cells (43, 59, 66, 74).

In S. cerevisiae, the separase-generated C-terminal fragment of the Scc1 cohesin subunit bears N-terminal Arg. This fragment of Scc1 forms late in mitosis upon the activation of separase and is rapidly destroyed by the Arg/N-end end rule pathway (62). A failure to eliminate this (normally short-lived) Scc1 fragment (e.g. in a ubr1Δ mutant that lacks the Arg/N-end rule pathway) results in chromosome instability (62). The C-terminal fragment of Scc1 retains a physical affinity for the rest of the cohesin complex (62). Therefore, the plausible (but not proven) cause of chromosome instability in ubr1Δ cells is an interference with cohesin mechanics by the metabolically stabilized, cohesin-bound C-terminal fragment of Scc1. Because the yeast Scc1 fragment bears N-terminal Arg, the fragment's degradation by the Arg/N-end rule pathway does not require Nt-arginylation (62). In mammals, however, the separase-generated C-terminal fragments of the Rad21 subunit of mitotic cohesin and the Rec8 subunit of meiotic cohesin bear N-terminal Glu, a substrate of the Ate1 R-transferase (Fig. 1, A and C) (47, 75, 76).

In the present work, we constructed an Ate1−/− mouse strain in which the ablation of Ate1 was confined to germ cells. We show that the separase-generated C-terminal fragment of Rec8, a subunit of meiotic cohesin, is a short-lived physiological substrate of the Arg/N-end rule pathway and that the degradation of this Rec8 fragment requires its Nt-arginylation. These and related results suggest that a failure to destroy this fragment in arginylation-lacking spermatocytes of Ate1−/− mice contributes to a greatly reduced male fertility of these mice, due to the observed arrest and apoptotic death of Ate1−/− spermatocytes at the end of meiosis I. These results expand the already large set of functions of the Arg/N-end rule pathway. Together with earlier data about Ate1−/− and Ubr2−/− mice (33, 77), the present findings also indicate that perturbations of the Arg/N-end rule pathway may be among the causes of infertility in humans.

Experimental Procedures

Mutant Mouse Strains

Conditional (cre-lox-based) Ate1flox/floxmice were described (33). Tnap-Cre mice, in which the Cre recombinase is selectively expressed in primordial germ cells (78), were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Germ-cell specific Ate1−/− mouse strains were constructed in the present study through matings of Ate1flox/flox mice (33) and Tnap-Cre mice (78). All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Research Panel of the Committee on Research Practice of the University of the Chinese Academy of Science.

Antibodies

Mouse anti-Sycp3 monoclonal antibody (SC-74569) and mouse anti-PLZF monoclonal antibody (SC-28319) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Dallas, TX). Rabbit anti-Sycp3 polyclonal antibody (ab150292) and rabbit anti-Rec8 polyclonal antibody were from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Mouse anti-MLH1 monoclonal antibody (51-1327GR) was from BD Pharmingen (San Jose, CA). Rabbit anti-Sycp1 polyclonal antibody-Cy5 (NB300-228c) was from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO). Mouse anti-cyclin B1 monoclonal antibody (MA5-14319) was from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA). FITC-conjugated mouse monoclonal anti-α-tubulin antibody (F2168) was from Sigma-Aldrich. FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody and TRITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody, as well as horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody, were from Zhong Shan Jin Qiao (Beijing, China). Alexa Fluor 680-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody and Alexa Fluor 680-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody were from Invitrogen.

Male Fertility Assays

Breeding assays with wild-type and Ate1−/− male mice were carried out as described previously (79). Briefly, each examined male mouse (8–9 weeks old) was caged with two wild-type (CDI strain) female mice (6–8 weeks old), and their vaginal plugs were checked every morning. The number of pups produced by each pregnant female was counted within a week after birth. Each male was tested through at least six cycles of this breeding assay.

Epididymal Sperm Count

The cauda epididymis was dissected from adult mice. Sperm was released by cutting the cauda epididymis into pieces, placing them in 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and incubating for 10 min at 37 °C. Thereafter, 10-μl samples were transferred to a hemocytometer for counting sperm cells.

Immunoblotting and Related Procedures

Extracts from testes were prepared using a Dounce homogenizer in a cold high salt radioimmune precipitation assay-like buffer (0.5 m NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 2 mm Na-EDTA, 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6) supplemented with 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and a protein inhibitor mixture (Roche Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland), 04693132001). Extracts were centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 15 min. Samples of supernatants were fractionated by SDS-PAGE (NuPAGE 4–12% BisTris gel; Invitrogen) and electrotransferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, followed by incubation for 2–4 h at room temperature with a primary antibody, a further incubation with the HRP-conjugated secondary antibody, washes, and the detection of immunoblotting patterns using chemiluminescence, largely as described (18, 80).

The Ubiquitin Reference Technique (URT) and Analyses of Rec8 in Reticulocyte Extract

The mouse Rec8 open reading frame (ORF) was amplified by PCR, using cDNA from GE Healthcare Dharmacon (Clone ID: 6335959) (Pittsburgh, PA). The resulting DNA fragments were cut with SacII and ClaI and cloned into SacII/ClaI-cut pKP496, yielding the plasmids pBW442, pBW443, and pBW444, respectively. pKP496 was an AmpR, NeoR, pcDNA3-based plasmid encoding FLAG-DHFR-HA-UbK48R-MCS (multiple cloning site)-FLAG under the control of the PCMV promoter (21). pBW442, pBW443, and pBW444 expressed fDHFR-HA-UbK48R-Glu455-Rec8f, fDHFR-HA-UbK48R-Val455-Rec8f, and fDHFR-HA-UbK48R-Arg-Glu455-Rec8f, respectively, from the PCMV promoter. The plasmid pcDNA3MR8, expressing fDHFR-HA-UbK48R-Met206-Rec8f, was constructed similarly.

Rabbit reticulocyte-based degradation assays were carried out using the TNT T7 coupled transcription/translation system (Promega, Madison, WI), largely as described previously (21–23). Nascent proteins translated in the extract were pulse-labeled with l-[35S]methionine (0.55 mCi/ml, 1,000 Ci/mmol, MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA) for 10 min at 30 °C in a total volume of 30 μl. Labeling was quenched by the addition of 0.1 mg/ml cycloheximide and 5 mm unlabeled methionine, bringing the final reaction volume to 40 μl. Samples of 10 μl were removed at the indicated time points, and the reaction was terminated by the addition of 80 μl of TSD buffer (1% SDS, 5 mm dithiothreitol (DTT), 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4), snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until use. Following the collection of all time points, samples were heated at 95 °C for 10 min and then diluted with 1 ml of TNN buffer (0.5% Nonidet P-40, 0.25 m NaCl, 5 mm Na-EDTA, 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4) containing 1× Complete protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Diagnostics) and immunoprecipitated using 5 μl of anti-FLAG M2 magnetic beads (Sigma-Aldrich). Samples were incubated with rotation at 4 °C for 4 h, followed by three washes in TNN buffer, a wash in 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.5, and resuspension in 20 μl of SDS-sample buffer. Samples were heated at 95 °C for 5 min and fractionated by SDS-10% PAGE, followed by autoradiography and quantification, using a Typhoon-9500 Imager and ImageQuant (GE Healthcare).

Reticulocyte extract-based assays in which Rec8f, its derivatives, and the fDHFR-HA-UbK48R reference protein were detected by immunoblotting were carried out similarly, except that no [35S]Met/Cys labeling was involved. The synthesis-deubiquitylation-degradation of URT-based test fusions was allowed to proceed for 1 h at 30 °C either in the absence of added dipeptides or in the presence of either Arg-Ala (1 mm) or Ala-Arg (1 mm), followed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-FLAG antibody (Fig. 5E).

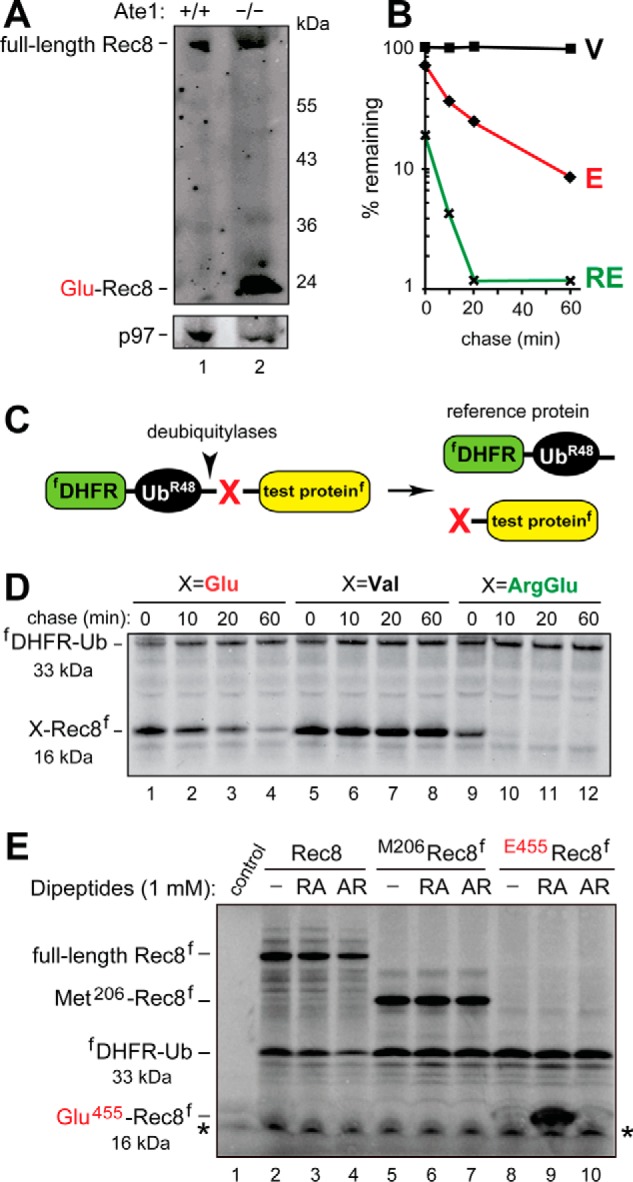

FIGURE 5.

The separase-generated C-terminal fragment of Rec8 as a short-lived substrate of the Arg/N-end rule pathway. A, immunoblotting of extracts from wild-type (lane 1) versus Tnap-Ate1−/− (lane 2) mouse testes with antibody to a C-terminal region of Rec8. Note the presence of a prominent band, inferred to be the endogenous Glu455-Rec8 fragment, in Tnap-Ate1−/− but not wild-type testes. The bottom panel shows the results of control immunoblots using antibody to the unrelated p97 protein. B, quantification of data in D. C, the URT (see “Experimental Procedures”). D, lanes 1–4, 35S-pulse-chase of the C-terminally FLAG-tagged Glu455-Rec8f fragment of mouse Rec8, produced as the URT fusion fDHFR-UbR48-Glu455-Rec8f in reticulocyte extract (see “Experimental Procedures”). The bands of Glu455-Rec8f and the reference protein fDHFR-UbR48 are indicated on the left. Lanes 5–8, same as in lanes 1–4 but with the otherwise identical Val455-Rec8f, bearing N-terminal Val, which is not targeted by the Arg/N-end rule pathway. Lanes 9–12, same as in A but with Arg-Glu455-Rec8f (see “Experimental Procedures”). E, in these assays, the synthesis-deubiquitylation-degradation of URT-based fDHFR-UbR48-X-Rec8f fusions in reticulocyte extract was allowed to proceed for 1 h, followed by detection of Glu455-Rec8f, of other test proteins, and of the fDHFR-UbR48 reference protein by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-FLAG antibody. Lane 1, control extract with the added vector plasmid (see “Experimental Procedures”). Lane 2, expression of the fDHFR-UbR48-Rec8f fusion, which is processed by deubiquitylases in the extract to yield full-length Rec8f. Lane 3, same as lane 2 but in the presence of the Arg-Ala (RA) dipeptide at 1 mm. Lane 4, same as lane 3 but in the presence of the Ala-Arg (AR) dipeptide at 1 mm. Lanes 5–7, same as lanes 2–4 but with expression of the fDHFR-UbR48-Met206-Rec8f fusion, which is processed in the extract to yield fDHFR-UbR48 and Met206-Rec8f (see “Experimental Procedures”). Lanes 8–10, same as lanes 5–7 but with expression of the fDHFR-UbR48-Glu455-Rec8f fusion, which is processed in the extract to yield fDHFR-UbR48 and the Glu455-Rec8f protein, the main product of the cleavage of full-length Rec8 by separase. Note the presence of a prominent protein band, inferred to be the 16-kDa FLAG-tagged Glu455-Rec8f protein, in the presence of the Arg-Ala dipeptide (lane 9) but neither in the absence of added dipeptide nor in the presence of Ala-Arg (lanes 8 and 10; see also “Experimental Procedures”). Also indicated in D and E, are the molecular masses of key protein species, the C-terminally FLAG-tagged Rec8 fragment (16 kDa) and the N-terminally FLAG-tagged reference protein DHFR-Ub (33 kDa). An asterisk denotes a protein band that cross-reacted with anti-FLAG antibody.

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

For histological analyses, testes and epididymis were fixed, after dissection, in 4% paraformaldehyde (formaldehyde, HCHO) (Solarbio (Beijing, China), P1110) overnight at 4 °C, followed by standard procedures (79). Briefly, tissues were dehydrated through a series of ethanol washes and thereafter embedded in paraffin wax. Sections (5 μm thick) were produced using a microtome. Deparaffinized and rehydrated sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histological observations. For immunohistochemical assays, deparaffinized and rehydrated sections were rinsed three times at room temperature in PBS (pH 7.4), followed by antigen retrieval by boiling for 15 min in 10 mm sodium citrate, pH 6.0. Sections were then incubated for 10 min at room temperature with 3% H2O2, followed by blocking of each section by incubating it for 30 min at room temperature in 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma). Sections were incubated with a primary antibody at 4 °C overnight, followed by incubation with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody at 37 °C for 1 h. Sections were then stained with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine according to the manufacturer's instructions (Zhong Shan Jin Qiao, ZL1-9018), and nuclei were stained with hematoxylin. Negative controls were processed identically but without the primary antibody. Sections were examined using a Nikon 80i inverted microscope with a charge-coupled camera.

Spread of Spermatocyte Nuclei

Spermatocyte nuclei were prepared as described previously (81) with modifications. Briefly, testes were washed in PBS after dissection from mice. The tunicae were removed, and adherent extratubular tissues were removed by rinsing the seminiferous tubules with PBS at room temperature. The tubules were placed in a hypotonic extraction buffer (50 mm sucrose, 17 mm sodium citrate, 0.5 mm DTT, 0.5 mm PMSF, 3 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.2) for 30–60 min. Thereafter, ∼1 inch of tubule was shredded to pieces by fine tipped forceps in 20 μl of 0.1 m sucrose (pH adjusted to pH 8.2 by NaOH) on a clean glass slide. Another 20 μl of sucrose solution was then added, and a slightly cloudy suspension was prepared, using a pipettor. Residual tubular tissues were removed. The suspension was transferred onto a new precoated (3-aminopropyl-triethoxysilane (Zhong Shan Jin Qiao, ZL1–9002)) glass slides, each of them containing on the surface 0.1 ml of freshly made (and filtered through a 0.22-μm Rephile filter (Rephile (Shanghai, China), RJP3222SH)) solution of 1% paraformaldehyde (PFA), 0.15% Triton X-100 (with pH adjusted to 9.2 using 10 mm sodium borate, pH 9.2). Each slide was gently rocked to mix the initial suspension with PFA solution, followed by drying for at least 2 h in a closed box with high humidity. To stain the resulting nuclei spreads, slides were washed with 0.4% Photoflo (Eastman Kodak Co.) three times and with PBS three times and then blocked in 5% BSA for 1 h, incubated with a primary antibody in 1.5% BSA and 0.3% Triton X-100 overnight at 4 °C, and then incubated with secondary antibody in PBS for 1 h at 37 °C. The resulting slides were washed in PBS, and nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Slides were examined using an LSM 780/710 microscope (Zeiss).

TUNEL Assays

TUNEL assays were carried out using the In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche Diagnostics, 11684795910) as described by us previously (82). Briefly, sections of testis were heated at 60 °C for 2 h, followed by washing in xylene and rehydration through a graded series of washes with ethanol and double-distilled water. Thereafter, the sections were treated with proteinase K for 15 min at room temperature and rinsed twice with PBS. After adding the TUNEL reaction mixture, slides were incubated in a humidified atmosphere for 60 min at 37 °C in the dark, followed by staining with DAPI (82). All experiments were repeated at least three times, with S.D. values shown.

Results

Germ Cell-specific Ablation of the Ate1 R-transferase Strongly Decreases Fertility of Male Mice

Probing sections of mouse testis with affinity-purified antibody to mouse Ate1 indicated the presence of the Ate1 R-transferase in the testis, particularly in spermatocytes and spermatogonia (precursors of spermatocytes) (Fig. 2A). These immunohistochemical results were in agreement with in situ hybridization data about Ate1 expression in spermatocytes (77). To produce mouse strains in which Ate1 was selectively ablated in primordial germ cells, we mated the previously constructed Ate1flox/flox mice (33) with Tnap-Cre mice expressing Cre recombinase from the primordial germ cell-specific Tnap promoter (78) (see “Experimental Procedures”). Immunoblotting analyses of testis extracts from the resulting Tnap-Ate1−/− mice versus Ate1flox/flox (wild-type) mice with anti-Ate1 antibody indicated a dramatic decrease of Ate1 in Tnap-Ate1−/− testes (Fig. 2B). Inasmuch as spermatogonia and spermatocytes (in which Tnap-Cre was selectively expressed) comprise a large fraction but not the entirety of testicular cells, these results (Fig. 2B) indicated that the Ate1 R-transferase was either completely or nearly completely absent from spermatogonia and spermatocytes of Tnap-Ate1−/− mice.

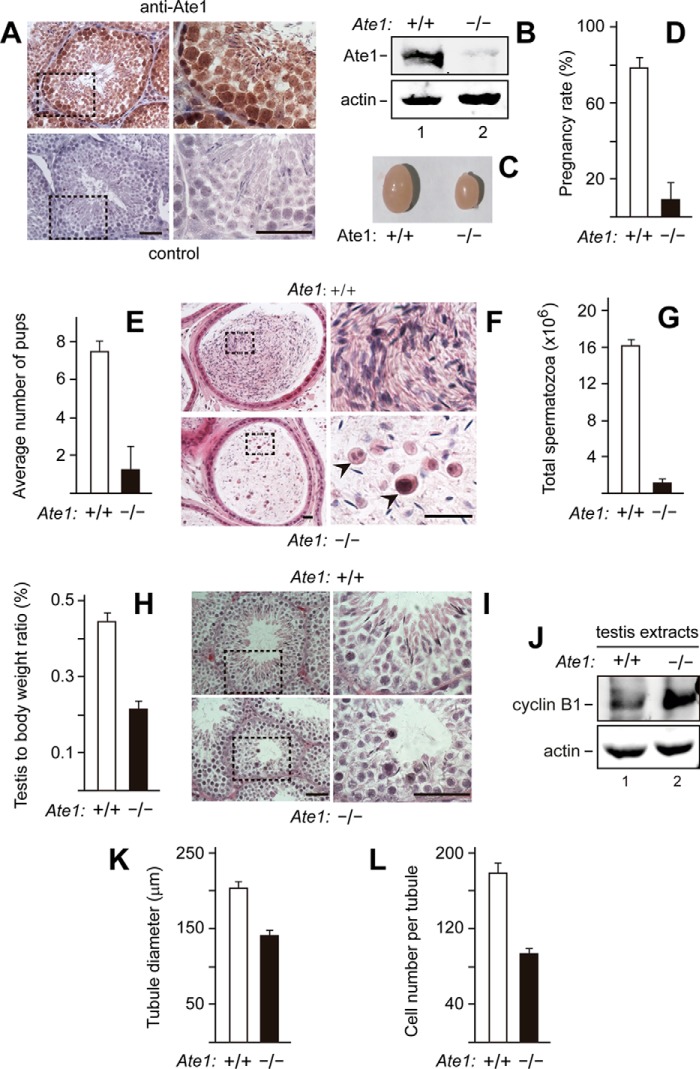

FIGURE 2.

Tnap-Ate1−/− mice, in which the ablation of Ate1 is confined to germ cells, are nearly infertile. A, immunohistochemical detection of the Ate1 R-transferase in sections of wild-type (Ate1flox/flox) seminiferous tubules in adult mice, using affinity-purified anti-Ate1 antibody. Subpanels on the right are enlargements of the areas demarcated by dashed rectangles on the left. Top subpanels, staining with primary (anti-Ate1) and secondary antibodies. Bottom subpanels, secondary antibody alone (control). Scale bars, 50 μm. B, dramatic decrease of the Ate1 R-transferase in the testes of Tnap-Ate1−/− mice, as determined by immunoblotting of testes extracts with anti-Ate1 antibody. C, decreased size of Tnap-Ate1−/− testes, in comparison with wild-type (Ate1flox/flox) ones. D, pregnancy rates (%) of plugged wild-type females after matings with Tnap-Ate1−/− versus wild-type males. E, average numbers of pups per all plugged wild-type females after matings with Tnap-Ate1−/− versus wild-type males. F, histological appearance (hematoxylin-eosin) of sections through epididymis of Tnap-Ate1−/− versus wild-type males. Subpanels on the right are enlargements of areas (indicated by dashed rectangles) on the left. Arrowheads, abnormal cells, absent in sections of wild-type epididymis. Scale bar, 20 μm. G, calculated total sperm number in epididymis of Tnap-Ate1−/− versus wild-type males. H, ratio of testis mass to mouse body mass for Tnap-Ate1−/− versus wild-type males. I, histological appearance (hematoxylin-eosin) of sectioned seminiferous tubules in Tnap-Ate1−/− versus wild-type males. Scale bars, 50 μm. J, immunoblotting analyses, using antibodies to actin and to cyclin B1 (the latter a marker for metaphase) of extracts from Tnap-Ate1−/− versus wild-type testes (see “Results”). K, average diameters of seminiferous tubules in Tnap-Ate1−/− versus wild-type testes. L, average numbers of cells per seminiferous tubule in Tnap-Ate1−/− versus wild-type testes. S.D. values (error bars) are indicated in D, E, G, H, K, and L (the corresponding assays were carried out in triplicate).

Fertility of Tnap-Ate1−/− and “wild-type” Ate1flox/flox males was assessed by mating three males of each strain with wild-type females. For each male mouse, at least six plugged females were collected, and the pregnancy rates were recorded. Only ∼9% of plugged females became pregnant after mating with Tnap-Ate1−/− male mice, in comparison with a pregnancy rate of ∼78% after mating with Ate1flox/flox males (Fig. 2D). In addition, the average number of pups born to females that were mated with Tnap-Ate1−/− males was only ∼1.3, in contrast to ∼7.3 pups that were born, on average, to Ate1flox/flox females mated to Ate1flox/flox males (Fig. 2E).

In agreement with the low fertility of Tnap-Ate1−/− males (Fig. 2, D and E), hematoxylin/eosin-stained sections of their epididymides contained few apparently mature spermatozoa (∼1 × 106/epididymis), in contrast to the much larger number (∼16 × 106/epididymis) of mature spermatozoa in Ate1flox/flox males (Fig. 2, G and I). In contrast to Ate1flox/flox males, the epididymides of Tnap-Ate1−/− males contained a number of round-shaped cells with large nuclei, possibly immature spermatids (Fig. 2F). In agreement with these results, Tnap-Ate1−/− testes were considerably smaller and lighter than their Ate1flox/flox counterparts (Fig. 2, C and H). Histological assays also showed that the average diameter of seminiferous tubules in Tnap-Ate1−/− testes was ∼139 μm, in contrast to ∼204 μm for Ate1flox/flox tubules, and that Tnap-Ate1−/− tubules contained a smaller average number of cells per section (∼93 cells versus ∼177 cells, respectively) (Fig. 2, K and L).

These results (Fig. 2) indicated that the Ate1 R-transferase was required for normal fertility levels in male mice. Given very low but still non-zero fertility of Ate1−/− males (Fig. 2, D and E) as well as complete or nearly complete absence of the Ate1 R-transferase from germ cells in Tnap-Ate1−/− testes (Fig. 2B), it is formally possible that the total absence of the Ate1-mediated arginylation in spermatogonia and spermatocytes is still compatible with a low but non-zero probability of sperm maturation. The alternative and a priori more likely interpretation is that the low but detectable sperm maturation that underlies the residual fertility of Tnap-Ate1−/− mice (Fig. 2, D and E) is made possible by rare spermatocytes of Tnap-Ate1−/− testes that retained at least one copy of the intact Ate1flox gene.

The Absence of Arginylation Is Compatible with Early Stages of Germ Cell Development

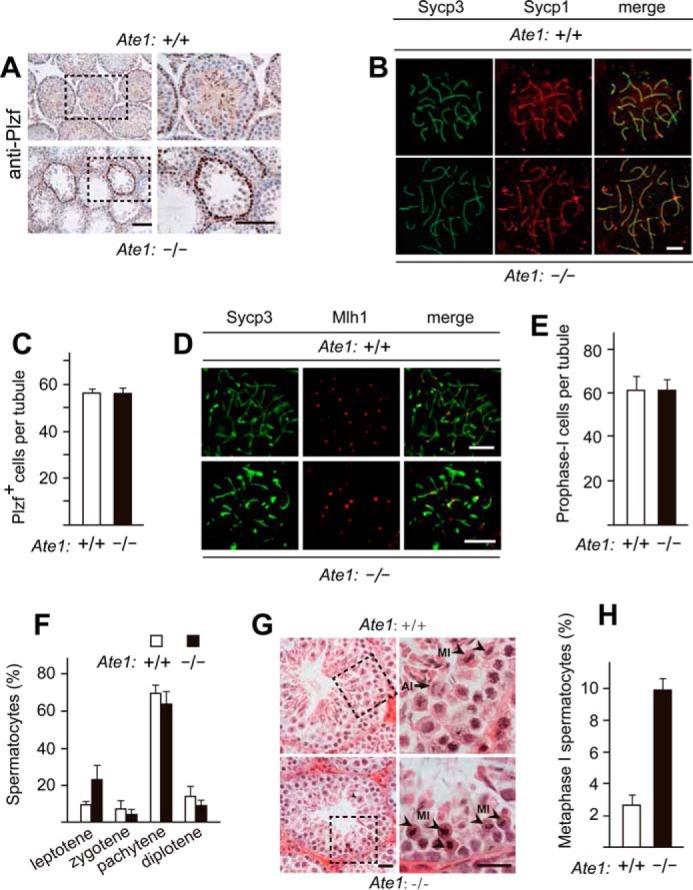

Using an antibody to the promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger (Plzf), a spermatogonia-specific marker, we observed similar levels of Plzf in presumptive spermatogonia in either the absence or presence of Ate1 (∼56 Plzf-positive cells, on average, per section of seminiferous tubule in both Tnap-Ate1−/− and Ate1flox/flox mice) (Fig. 3, A and C). Formation of the synaptonemal complex and synapsis of chromosomes during the prophase of meiosis I in spermatocytes is accompanied by expression of the synaptonemal complex proteins 1 and 3 (Sycp1 and Sycp3) (83–85). Antibodies to Sycp1 and Sycp3 stained meiotic chromosomes indistinguishably in chromosome spreads of either Tnap-Ate1−/− or Ate1flox/flox spermatocytes (Fig. 3B). Similar immunofluorescence assays with Mlh1, a marker for chromosome crossovers (86–89), also showed no significant differences between Tnap-Ate1−/− and Ate1flox/flox spermatocytes (Fig. 3, B, D, and E).

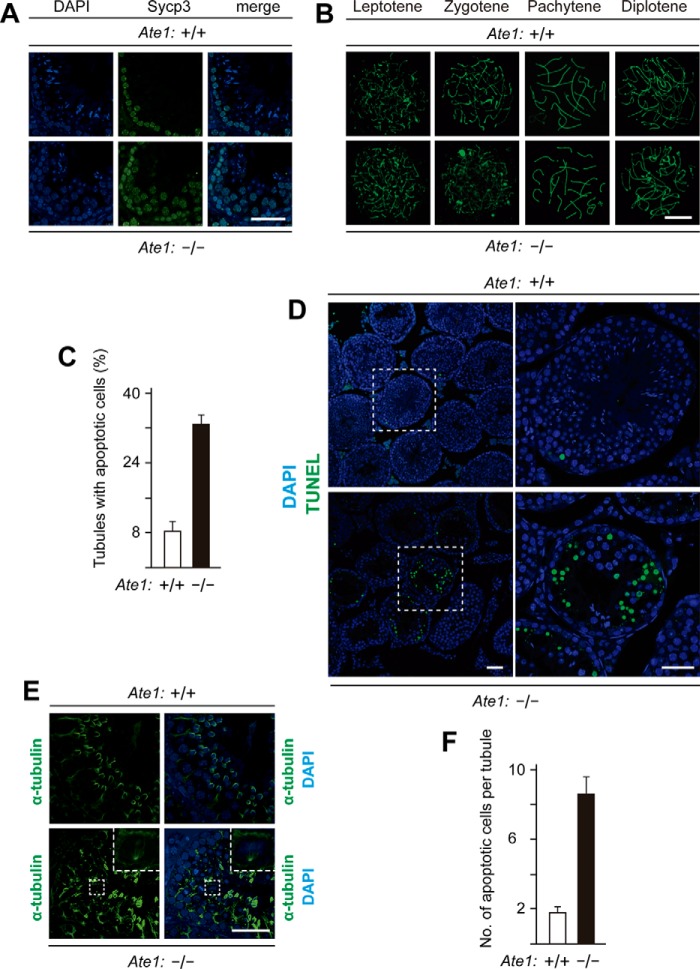

FIGURE 3.

Knock-out of the Ate1 R-transferase gene does not affect the progression of spermatocytes through meiosis I until their arrest at metaphase. A, similar frequencies of cells (Plzf+ cells) that could be stained with antibody to Plzf, a spermatogonia-specific marker, in testes of Tnap-Ate1−/− versus wild-type males. Scale bars, 50 μm. B, Sycp3 (green) and Sycp1 (red) proteins, the markers for synaptonemal complex, detected (using corresponding antibodies) on chromosomes of Tnap-Ate1−/− versus wild-type spermatocytes at the pachytene stage of meiosis I. Scale bars, 5 μm. C, numbers of Plzf+ cells (presumptive spermatogonia) per section of a seminiferous tubule in Tnap-Ate1−/− versus wild-type males (quantification of results in A). D, same as in B but for Sycp3 and Mlh1 (the latter a marker for chromosome crossovers) in Tnap-Ate1−/− versus wild-type males. Scale bars, 5 μm. E, numbers of prophase I (Sycp3-positive) cells per section of a seminiferous tubule in Tnap-Ate1−/− versus wild-type males. F, percentages of spermatocytes at different prophase stages of meiosis I Tnap-Ate1−/− versus wild-type males. G, sections of Tnap-Ate1−/− versus wild-type testes were stained with hematoxylin/eosin. Subpanels on the right are enlargements of the areas demarcated by dashed rectangles on the left. An arrow and arrowheads indicate anaphase and metaphase cells, respectively. Scale bars, 50 μm. H, percentages of spermatocytes at metaphase I of meiosis I (quantification of cell images in G). S.D. values (error bars) are indicated in C, E, F, and H (the corresponding assays were carried out in triplicate).

In addition, we could readily identify, cytologically, every major stage of the prophase of meiosis I in both Tnap-Ate1−/− and Ate1flox/flox spermatocytes, including leptotene, zygotene, pachytene, and diplotene, and there were no statistical significant differences between the two genotypes vis-á-vis the percentages of each stage of prophase I (Figs. 3 (E and F) and 4 (A and B)). The average numbers of spermatocytes per seminiferous tubule section in the prophase of meiosis I were also similar between Tnap-Ate1−/− and Ate1flox/flox mice (∼61 and ∼60 spermatocytes, respectively) (Fig. 3E). These results indicated that (at resolution levels of our assays) premetaphase stages of germ cell development did not require the Ate1 R-transferase.

FIGURE 4.

Increased apoptosis in seminiferous tubules of Tnap-Ate1−/− mice. A, spermatocytes in prophase I of meiosis I, stained with DAPI for DNA and with anti-Sycp3 antibody in sections of seminiferous tubes in Tnap-Ate1−/− versus wild-type testes. Scale bar, 50 μm. B, stages of meiosis I in spermatocytes of Tnap-Ate1−/− versus wild-type testes, detected by staining chromosome spreads with anti-Sycp3 antibody. Scale bar, 10 μm. C, percentages of seminiferous tubules containing apoptotic (TUNEL-positive) cells in Tnap-Ate1−/− versus wild-type testes. D, representative TUNEL assay patterns (stained with DAPI as well) in Tnap-Ate1−/− versus wild-type testes. Subpanels on the right are enlargements of areas (indicated by dashed squares) on the left. Scale bars, 50 μm. E, staining of testes sections from Tnap-Ate1−/− versus wild-type testes with DAPI for DNA and with antibody to α-tubulin for spindle bodies (see “Results”). Scale bar, 50 μm. F, numbers of apoptotic (TUNEL-positive) cells per section of seminiferous tubules in Tnap-Ate1−/− versus wild-type testes. S.D. values (error bars) are indicated in C and F (the corresponding assays were carried out in triplicate).

Lack of Arginylation Causes Metaphase Arrest in Meiosis I

In contrast to the absence of detectable defects in the progression of Ate1-lacking Tnap-Ate1−/− spermatocytes through the prophase of meiosis I, we found these cells to be arrested at the metaphase of meiosis I, followed by their death through apoptosis (Figs. 3 (G and H) and 4 (C, D, and F)). In stage XII seminiferous tubules, metaphase I spermatocytes could be identified by their highly condensed (hematoxylin-stained) chromatin (74) (Fig. 3, G and H). Both metaphase and later stage (anaphase) spermatocytes (indicated by arrowheads and arrows, respectively) could be observed in Ate1-containing tubules of Ate1flox/flox testes (Fig. 3G). However, no anaphase spermatocytes could be detected in tubules of Ate1-lacking Tnap-Ate1−/− testes, whose relative content of metaphase spermatocytes was ∼9.9%, in contrast to ∼2.6% of such cells in Ate1flox/flox testes (Fig. 3, G and H). In agreement with these results, it was easy to detect spindle bodies marked by α-tubulin (consistent with the arrest of metaphase I spermatocytes) in Tnap-Ate1−/− testes (Fig. 4E). We also examined, by immunoblotting, the expression of cyclin B1, a marker of metaphase (90). The level of cyclin B1 was significantly increased in Tnap-Ate1−/− testes (Fig. 2J), yet another indication of metaphase arrest of Ate1-lacking spermatocytes in meiosis I.

Apoptotic Death of Arginylation-lacking Spermatocytes in Metaphase of Meiosis I

The terminal TUNEL assay was used to measure the extent of apoptosis of Tnap-Ate1−/− versus Ate1flox/flox spermatocytes (Fig. 4, C, D, and F). In Tnap-Ate1−/− testes, on average ∼33% of spermatocytes were overtly apoptotic (TUNEL-positive), in comparison with ∼9% of such cells in Ate1-containing Ate1flox/flox testes (Fig. 4C). In addition, only ∼1.8 apoptotic cells/seminiferous tubule section were found, on average, in Ate1flox/flox testes, versus ∼8.3 apoptotic cells in Tnap-Ate1−/− testes (Fig. 4F). Together, these results are likely to account for the observed massive decrease in the content of mature sperm cells in the testes of Ate1-lacking Tnap-Ate1−/− males and the resulting very low fertility of these mice (Fig. 2, C–E). As described below, the metabolic stabilization of a natural fragment of the meiosis-specific Rec8 cohesin subunit is likely to be at least a significant, and possibly the major, reason for this functional consequence of Ate1 ablation in germ cells.

Arginylation-mediated Degradation of the Separase-produced Rec8 Fragment

Rec8 is the main meiosis-specific cohesin subunit of the kleisin family. Mouse Rec8 is sequelogous to both yeast and mammalian kleisin-type cohesin subunits (see Fig. 1C and Introduction). The cleavage of mouse Rec8 by the separase would be expected to generate a 15-kDa C-terminal fragment bearing N-terminal Glu, a secondary destabilizing residue and a substrate of the Ate1 R-transferase (Fig. 1, A and C). Although separase can cleave mouse Rec8 in vitro at more than one location, the cleavage between Arg-454 and Glu-455 is by far the predominant one (Fig. 1C) (76).

To determine whether the separase-generated Rec8 fragment was a substrate of the Arg/N-end rule pathway, we used both steady-state and pulse-chase assays. Immunoblotting of extracts from wild-type and Tnap-Ate1−/− mouse testes with antibody to a C-terminal region of Rec8 showed the presence of both the full-length endogenous Rec8 protein and its fragment. The latter species migrated, upon SDS-PAGE, at a position close to the one expected for the 15-kDa Glu455-Rec8 fragment (Figs. 1C and 5A, lane 2). Strikingly, however, whereas this endogenous Rec8 fragment was abundant in extracts from Tnap-Ate1−/− testes, it was virtually absent in wild-type extracts (Fig. 5A, lane 1 versus lane 2).

A parsimonious interpretation of these results is that the separase-generated 15-kDa Glu455-Rec8 fragment (Fig. 1C) (76) was arginylated by the Ate1 R-transferase in wild-type cells and thereafter rapidly destroyed by the “downstream” part of the Arg/N-end rule pathway, whereas in Tnap-Ate1−/− cells, the Glu455-Rec8 fragment was long-lived, because it could not be arginylated (Figs. 1A and 5A); hence, the virtual absence of the endogenous Glu455-Rec8 fragment in wild-type testes at steady state (Fig. 5A, lane 1) and its accumulation in Tnap-Ate1−/− testes (Fig. 5A, lane 2). Interestingly, the level of the full-length Rec8 protein was also considerably higher in Tnap-Ate1−/− testes than in wild-type ones, at equal total protein loads (see Fig. 5A and “Discussion”).

Degradation of the Glu455-Rec8 fragment was also assayed directly, using 35S-pulse-chases and the URT, derived from the Ub fusion technique (Fig. 5C) (4, 21, 22, 91, 92). Cotranslational cleavage of a URT-based Ub fusion by deubiquitylases that are present in all eukaryotic cells produces, at the initially equimolar ratio, both a test protein with a desired N-terminal residue and the reference protein fDHFR-UbR48, a FLAG-tagged derivative of the mouse dihydrofolate reductase (Fig. 5C). In URT-based pulse-chase assays, the labeled test protein is quantified by measuring its levels relative to the levels of a stable reference at the same time point during a chase. In addition to being more accurate than pulse-chases without a built-in reference, URT also makes it possible to detect and measure the degradation of the test protein before the chase (i.e. during the pulse) (17, 91, 92).

URT-based 35S-pulse-chases with C-terminally FLAG-tagged Glu455-Rec8f and its derivatives were performed in a transcription-translation-enabled rabbit reticulocyte extract, which contains the Arg/N-end rule pathway and has been extensively used to analyze this pathway (4, 21, 22). The indicated fDHFR-UbR48-X455-Rec8f URT fusions (where X represents Glu, Val, or Arg-Glu) were labeled with [35S]Met/Cys in reticulocyte extract for 10 min at 30 °C, followed by a chase, immunoprecipitation with a monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody, SDS-PAGE, autoradiography, and quantification (Fig. 5, B–D). The logic of these assays involves a comparison between the degradation rates of a protein bearing a destabilizing N-terminal residue and an otherwise identical protein with an N-terminal residue, such as Val, which is not recognized by the Arg/N-end rule pathway (Fig. 1A).

The Glu455-Rec8f fragment was short-lived in reticulocyte extract (t½ of 10–15 min) (Fig. 5, B and D). Moreover, ∼30% of pulse-labeled Glu455-Rec8f was degraded during the pulse (i.e. before the chase) in comparison with the otherwise identical Val455-Rec8f, which was also completely stable during the chase (Fig. 5, B and D). We also constructed and examined Arg-Glu455-Rec8f. This protein was a DNA-encoded equivalent of the posttranslationally Nt-arginylated Glu455-Rec8f fragment of Rec8. As would be expected, given the immediate (cotranslational) availability of N-terminal Arg in the DNA-encoded Arg-Glu455-Rec8f, this protein was destroyed by the Arg/N-end rule pathway even more rapidly than the already short-lived Glu455-Rec8f. Specifically, nearly 80% of Arg-Glu455-Rec8f was eliminated during the 10-min pulse (before the chase), in comparison with ∼30% of Glu455-Rec8, with the long-lived Val455-Rec8f control being a part of the reference set (Fig. 5, B and D).

The results of pulse-chase analyses (Fig. 5, B–D) were in agreement with other measurements, in which the synthesis-deubiquitylation-degradation of fDHFR-UbR48-X-Rec8f fusions in reticulocyte extract was allowed to proceed for 1 h, followed by detection of Glu455-Rec8f, of other test proteins, and of the fDHFR-UbR48 reference protein by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-FLAG antibody (Fig. 5E). In these assays, the samples were incubated in reticulocyte extract either without added dipeptides or with 1 mm Arg-Ala (RA), bearing N-terminal Arg, a type 1 primary destabilizing residue, or with 1 mm Ala-Arg (AR), bearing N-terminal Ala, a residue that is not recognized by N-recognins of the Arg/N-end rule pathway (Figs. 1A and 5E).

Ubr1 and Ubr2, the two sequelogous (47% identical) and functionally overlapping 200-kDa N-recognins (E3 Ub ligases) of the mammalian Arg/N-end rule pathway, have several substrate-binding sites. These sites recognize (bind to) specific classes of N-degrons and specific internal (non-N-terminal) degrons. The two substrate-binding sites that recognize N-degrons are the type 1 site, which specifically binds to the N-terminal basic residues Arg, Lys, or His, and the adjacent but distinct type 2 site, which specifically binds to the N-terminal bulky hydrophobic residues Leu, Phe, Tyr, Trp, and Ile (4, 6, 93, 94). Dipeptides bearing, for example, type 1 N-terminal residues can competitively and selectively inhibit the binding of Ubr1/Ubr2 to a type 1 N-degron but not to a type 2 N-degron in a test protein (4, 6, 95–97).

In agreement with the rapid degradation of the Glu455-Rec8f fragment in 35S-pulse-chase assays (Fig. 5, B–D), the synthesis-deubiquitylation-degradation of the fDHFR-UbR48-Glu455-Rec8f fusion for 1 h in reticulocyte extract either in the absence of added dipeptide or in the presence of Ala-Arg (which does not bind to Ubr1/Ubr2) did not result in a detectable accumulation of the Glu455-Rec8f fragment, at its expected (roughly 15 kDa) position in SDS-PAGE-based immunoblots (Fig. 5E, lanes 8 and 10). In striking contrast, the same assay but in the presence of the Arg-Ala dipeptide (which competitively inhibits the recognition of type 1 N-degrons) resulted in a prominent protein band at the expected position of Glu455-Rec8f (Fig. 5E, lane 9 versus lanes 8 and 10). Given the URT-based design of fDHFR-UbR48-Glu455-Rec8f (Fig. 5C), that protein band was inferred to be the Glu455-Rec8f fragment that had been metabolically stabilized by the Arg-Ala dipeptide. In contrast, the larger Met206-Rec8f fragment, corresponding to a putative (and at most a minor) separase cleavage site in the full-length Rec8 protein, was metabolically stable irrespective of the presence or absence of the Arg-Ala dipeptide (Fig. 5E, lanes 5–7 versus lanes 8–10). The same was true of full-length Rec8f. It should also be mentioned that full-length Rec8f was not converted into a smaller fragment in reticulocyte extract, indicating (as would be expected) the absence of active separase in that extract (Fig. 5E, lanes 2–4).

Discussion

The arginyltransferase (R-transferase) Ate1 is a component of the Arg/N-end rule pathway of protein degradation. Ate1 utilizes Arg-tRNA as a cosubstrate to arginylate N-terminal Asp, Glu, or (oxidized) Cys of a targeted protein substrate. The resulting N-terminal Arg is recognized by E3 ubiquitin ligases (N-recognins) of the Arg/N-end rule pathway (see Fig. 1A and Introduction). In the present study, we constructed an Ate1−/− mouse strain in which the ablation of Ate1 was confined to germ cells. We used this and other experimental tools to characterize Glu455-Rec8, a specific C-terminal fragment of the kleisin-type, meiosis-specific Rec8 subunit of mouse cohesin. Rec8 is cleaved, late in meiosis I (see Introduction), by a nonprocessive protease called separase. The main C-terminal fragment of that cleavage, Glu455-Rec8, bears N-terminal Glu, a substrate of Ate1 (Fig. 1, A and C). We have shown that the mouse Glu455-Rec8 fragment is a short-lived substrate of the Arg/N-end rule pathway and that the degradation of this fragment requires its Nt-arginylation by the Ate1 R-transferase (Fig. 5).

In S. cerevisiae, Scc1/Rad21/Mcd1 is the mitotic counterpart of the mammalian meiotic Rec8 subunit of cohesin. Similarly to the mouse Glu455-Rec8 fragment, the separase-generated C-terminal fragment of yeast Scc1 is also a short-lived substrate of the Arg/N-end rule pathway, and the failure to destroy this fragment in ubr1Δ cells (which lack the Arg/N-end rule pathway) results in chromosome instability (62). The separase-generated C-terminal fragment of yeast Scc1 retains, in part, the physical affinity of Scc1 for the rest of the cohesin complex (62). The mouse Glu455-Rec8 fragment would also be likely to interact in vivo with the rest of meiotic cohesin. If so, the failure to arginylate the Glu455-Rec8 fragment in arginylation-lacking spermatocytes of Ate1−/− mice and hence the failure to destroy this fragment (Figs. 1A and 5) would be expected to interfere with cohesin mechanics. This (at present hypothetical) interference would account, at least in part, for the observed arrest and apoptotic death of Ate1−/− spermatocytes at the end of meiosis I and the resulting strong decrease in the fertility of Ate1−/− males (Fig. 2, C–L).

Immunoblotting analyses of the arginylation-dependent degradation of the endogenous Glu455-Rec8 fragment showed that this fragment was virtually absent, at steady state, in wild-type mouse testes but accumulated in Ate1−/− testes (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, the steady-state level of the full-length Rec8 protein was also significantly higher in Ate1−/− testes than in wild-type ones at equal total protein loads (Fig. 5A). A plausible but unproven interpretation of this result is that the cleavage of the full-length mouse Rec8 by separase may be subject to a product-mediated inhibition of separase in Ate1−/− spermatocytes if the product, Glu455-Rec8, is no longer eliminated by the Ate1-dependent arginylation branch of the Arg/N-end rule pathway (Figs. 1A and 5).

Although selective ablation of Ate1 in mouse germ cells nearly abrogates the fertility of male mice (Fig. 2, C–E), it is unlikely that specific cases of human infertility can be caused by unconditionally null mutations of human Ate1, inasmuch as global mouse Ate1−/− mutants are late embryonic lethals (29). In addition, a post-natal ablation of mouse Ate1, in adult mice (using cre-lox technology and a ubiquitously expressed Cre recombinase), although compatible with mouse viability, causes a variety of abnormal phenotypes, including the loss of fat and hyperkinetic behavior (33). Nevertheless, partially active (hypomorphic) mutants of the human Ate1 R-transferase might underlie some, currently obscure, cases of human infertility.

The same disposition would obtain if the human Arg/N-end rule pathway were to be partially inactivated “downstream” of the Ate1 R-transferase, at the level of the pathway's Ub ligases (Fig. 1A). For example, unconditional Ubr1−/− mice, lacking one of two major N-recognins, Ubr1 and Ubr2, are viable and fertile while exhibiting some abnormal phenotypes (98). The analogous Ubr2−/− mice, lacking the second major N-recognin (it is structurally and functionally similar to Ubr1), are also viable (in some strain backgrounds) but exhibit male infertility (77). This infertility is similar to the low fertility phenotype of Ate1−/− mice in the present study, because in both cases the infertility is caused by apoptotic death, in meiosis I, of either Ubr2−/− or Ate1−/− spermatocytes (Figs. 2 (C and D) and 4 (C, D, and F)). A parsimonious interpretation of these results is that a failure to rapidly destroy the separase-generated Glu455-Rec8 fragment is a common mechanistic denominator of both Ate1−/− and Ubr2−/− infertility phenotypes.

No human Ubr2−/− mutants have been identified so far. In contrast, human patients with the previously characterized Johansen-Blizzard syndrome have been shown to be null Ubr1−/− mutants (99). It is unknown whether or not human Johansen-Blizzard syndrome patients are fertile, in part because the overall phenotype of human Johansen-Blizzard syndrome is more severe than the analogous phenotype of Ubr1−/− mice. Abnormal phenotypes of human Johansen-Blizzard syndrome (Ubr1−/−) patients include anatomical malformations, an insufficiency and inflammation of the acinar pancreas, mental retardation, and deafness (4, 99).

Although separase can cleave mouse Rec8 in vitro at more than one site, the cleavage between Arg-454 and Glu-455, resulting in the Glu455-Rec8 fragment, is by far the predominant one (Fig. 1C) (76). Mammalian Rad21, the mitosis-specific counterpart of the meiotic Rec8 cohesin subunit, is also cleaved by separase, late in mitosis. Similarly to the cleavage of the meiosis-specific Rec8, the separase-mediated cleavage of the mammalian mitotic Rad21 subunit also yields the C-terminal fragment of Rad21 bearing N-terminal Glu (75). However, in contrast to the present results with the Glu455-Rec8 fragment of meiotic Rec8 (Fig. 5, B and D), our recent analyses of the N-terminal Glu-bearing mitotic Rad21 fragment using 35S-pulse-chases and the URT method (Fig. 5C) indicated that this fragment was long-lived.7 Further analyses of these unexpected (and therefore particularly interesting) results regarding the apparently stable mitotic Glu-Rad21 fragment vis-à-vis the short-lived meiotic Glu455-Rec8 fragment (Fig. 5) are under way.

Author Contributions

W. L. and the other coauthors of this paper designed the experiments. Y. J. L., C. L., Z. C., B. W., C. S. B., Z. H. S., Z. L. X., Y. L. S., W. X. L., L. N. W., and R.-G. H. performed the experiments. W. L., A. V., R. G. H., and W. D. wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to Qingyuan Sun (Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences) for anti-Rec8 antibody.

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 31171374 and 31471277 and Major Basic Research Program Grant 2012CB944404 (to W. L.) and by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-DK039520 and R01-GM031530 (to A. V.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

B. Wadas and A. Varshavsky, unpublished data.

- N-degron

- an N-terminal degradation signal recognized by the N-end rule pathway

- N-recognin

- an E3 ubiquitin ligase that can recognize at least some N-degrons

- Ub

- ubiquitin

- R-transferase

- arginyltransferase

- TRITC

- tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate

- BisTris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- Nt

- Nα-terminally

- PFA

- paraformaldehyde

- URT

- ubiquitin reference technique.

References

- 1. Bachmair A., Finley D., and Varshavsky A. (1986) In vivo half-life of a protein is a function of its amino-terminal residue. Science 234, 179–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hwang C. S., Shemorry A., and Varshavsky A. (2010) N-terminal acetylation of cellular proteins creates specific degradation signals. Science 327, 973–977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kim H. K., Kim R. R., Oh J. H., Cho H., Varshavsky A., and Hwang C. S. (2014) The N-terminal methionine of cellular proteins as a degradation signal. Cell 156, 158–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Varshavsky A. (2011) The N-end rule pathway and regulation by proteolysis. Protein Sci. 20, 1298–1345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gibbs D. J., Bacardit J., Bachmair A., and Holdsworth M. J. (2014) The eukaryotic N-end rule pathway: conserved mechanisms and diverse functions. Trends Cell Biol. 24, 603–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tasaki T., Sriram S. M., Park K. S., and Kwon Y. T. (2012) The N-end rule pathway. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 81, 261–289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dougan D. A., Micevski D., and Truscott K. N. (2012) The N-end rule pathway: from recognition by N-recognins to destruction by AAA+ proteases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1823, 83–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Varshavsky A. (2008) Discovery of cellular regulation by protein degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 34469–34489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bachmair A., and Varshavsky A. (1989) The degradation signal in a short-lived protein. Cell 56, 1019–1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Inobe T., and Matouschek A. (2014) Paradigms of protein degradation by the proteasome. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 24, 156–164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tobias J. W., Shrader T. E., Rocap G., and Varshavsky A. (1991) The N-end rule in bacteria. Science 254, 1374–1377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mogk A., Schmidt R., and Bukau B. (2007) The N-end rule pathway of regulated proteolysis: prokaryotic and eukaryotic strategies. Trends Cell Biol. 17, 165–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rivera-Rivera I., Román-Hernández G., Sauer R. T., and Baker T. A. (2014) Remodeling of a delivery complex allows ClpS-mediated degradation of N-degron substrates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, E3853–E3859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Piatkov K. I., Vu T. T. M., Hwang C.-S., and Varshavsky A. (2015) Formyl-methionine as a degradation signal at the N-termini of bacterial proteins. Microbial Cell 2, 376–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Humbard M. A., Surkov S., De Donatis G. M., Jenkins L. M., and Maurizi M. R. (2013) The N-degradome of Escherichia coli: limited proteolysis in vivo generates a large pool of proteins bearing N-degrons. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 28913–28924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Graciet E., Hu R. G., Piatkov K., Rhee J. H., Schwarz E. M., and Varshavsky A. (2006) Aminoacyl-transferases and the N-end rule pathway of prokaryotic/eukaryotic specificity in a human pathogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 3078–3083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shemorry A., Hwang C. S., and Varshavsky A. (2013) Control of protein quality and stoichiometries by N-terminal acetylation and the N-end rule pathway. Mol. Cell 50, 540–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Park S. E., Kim J. M., Seok O. H., Cho H., Wadas B., Kim S. Y., Varshavsky A., and Hwang C. S. (2015) Control of mammalian G protein signaling by N-terminal acetylation and the N-end rule pathway. Science 347, 1249–1252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Aksnes H., Hole K., and Arnesen T. (2015) Molecular, cellular, and physiological significance of N-terminal acetylation. Int. Rev. Cell. Mol. Biol. 316, 267–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Starheim K. K., Gevaert K., and Arnesen T. (2012) Protein N-terminal acettyltransferases: when the start matters. Trends Biochem. Sci. 37, 152–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Piatkov K. I., Brower C. S., and Varshavsky A. (2012) The N-end rule pathway counteracts cell death by destroying proapoptotic protein fragments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, E1839–E1847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Piatkov K. I., Oh J.-H., Liu Y., and Varshavsky A. (2014) Calpain-generated natural protein fragments as short-lived substrates of the N-end rule pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, E817–E826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brower C. S., Piatkov K. I., and Varshavsky A. (2013) Neurodegeneration-associated protein fragments as short-lived substrates of the N-end rule pathway. Mol. Cell 50, 161–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yamano K., and Youle R. J. (2013) PINK1 is degraded through the N-end rule pathway. Autophagy 9, 1758–1769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cha-Molstad H., Sung K. S., Hwang J., Kim K. A., Yu J. E., Yoo Y. D., Jang J. M., Han D. H., Molstad M., Kim J. G., Lee Y. J., Zakrzewska A., Kim S. H., Kim S. T., Kim S. Y., et al. (2015) Amino-terminal arginylation targets endoplasmic reticulum chaperone BiP for autophagy through p62 binding. Nat. Cell Biol. 17, 917–929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang H., Piatkov K. I., Brower C. S., and Varshavsky A. (2009) Glutamine-specific N-terminal amidase, a component of the N-end rule pathway. Mol. Cell 34, 686–695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hwang C. S., Shemorry A., Auerbach D., and Varshavsky A. (2010) The N-end rule pathway is mediated by a complex of the RING-type Ubr1 and HECT-type Ufd4 ubiquitin ligases. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 1177–1185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kwon Y. T., Kashina A. S., and Varshavsky A. (1999) Alternative splicing results in differential expression, activity, and localization of the two forms of arginyl-tRNA-protein transferase, a component of the N-end rule pathway. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 182–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kwon Y. T., Kashina A. S., Davydov I. V., Hu R.-G., An J. Y., Seo J. W., Du F., and Varshavsky A. (2002) An essential role of N-terminal arginylation in cardiovascular development. Science 297, 96–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hu R.-G., Sheng J., Qi X., Xu Z., Takahashi T. T., and Varshavsky A. (2005) The N-end rule pathway as a nitric oxide sensor controlling the levels of multiple regulators. Nature 437, 981–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hu R.-G., Brower C. S., Wang H., Davydov I. V., Sheng J., Zhou J., Kwon Y. T., and Varshavsky A. (2006) Arginyl-transferase, its specificity, putative substrates, bidirectional promoter, and splicing-derived isoforms. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 32559–32573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Saha S., and Kashina A. (2011) Posttranslational arginylation as a global biological regulator. Dev. Biol. 358, 1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Brower C. S., and Varshavsky A. (2009) Ablation of arginylation in the mouse N-end rule pathway: loss of fat, higher metabolic rate, damaged spermatogenesis, and neurological perturbations. PLoS One 4, e7757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brower C. S., Rosen C. E., Jones R. H., Wadas B. C., Piatkov K. I., and Varshavsky A. (2014) Liat1, an arginyltransferase-binding protein whose evolution among primates involved changes in the numbers of its 10-residue repeats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, E4936–E4945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang J., Han X., Saha S., Xu T., Rai R., Zhang F., Wolf Y. I., Wolfson A., Yates J. R. 3rd, and Kashina A. (2011) Arginyltransferase is an ATP-independent self-regulating enzyme that forms distinct functional complexes in vivo. Chem. Biol. 18, 121–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hu R.-G., Wang H., Xia Z., and Varshavsky A. (2008) The N-end rule pathway is a sensor of heme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 76–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Varshavsky A. (2004) Spalog and sequelog: neutral terms for spatial and sequence similarity. Curr. Biol. 14, R181–R183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lee M. J., Tasaki T., Moroi K., An J. Y., Kimura S., Davydov I. V., and Kwon Y. T. (2005) RGS4 and RGS5 are in vivo substrates of the N-end rule pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 15030–15035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Varshavsky A. (2012) Augmented generation of protein fragments during wakefulness as the molecular cause of sleep: a hypothesis. Protein Sci. 21, 1634–1661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Piatkov K. I., Colnaghi L., Békés M., Varshavsky A., and Huang T. T. (2012) The auto-generated fragment of the Usp1 deubiquitylase is a physiological substrate of the N-end rule pathway. Mol. Cell 48, 926–933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Crawford E. D., Seaman J. E., Agard N., Hsu G. W., Julien O., Mahrus S., Nguyen H., Shimbo K., Yoshihara H. A., Zhuang M., Chalkley R. J., and Wells J. A. (2013) The DegraBase: a database of proteolysis in healthy and apoptotic human cells. Mol. Cell Proteomics 12, 813–824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Singh V. P., and Gerton J. L. (2015) Cohesin and human disease: lessons from mouse models. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 37, 9–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rankin S. (2015) Complex elaboration: making sense of meiotic cohesin dynamics. FEBS J. 282, 2426–2443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hirano T. (2015) Chromosome dynamics during mitosis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 10.1101/cshperspect.a015792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Haarhuis J. H., Elbatsh A. M., and Rowland B. D. (2014) Cohesin and its regulation: on the logic of X-shaped chromosomes. Dev. Cell 31, 7–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bloom K. S. (2014) Centromeric heterochromatin: the primordial segregation machine. Annu. Rev. Genet. 48, 457–484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Peters J. M., and Nishiyama T. (2012) Sister chromatid cohesion. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 10.1101/cshperspect.a011130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nasmyth K., and Haering C. H. (2009) Cohesin: its roles and mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Genet. 43, 525–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Çamdere G., Guacci V., Stricklin J., and Koshland D. (2015) The ATPases of cohesin interface with regulators to modulate cohesin-mediated DNA tethering. eLife 10.7554/eLife.11315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ocampo-Hafalla M. T., Katou Y., Shirahige K., and Uhlmann F. (2007) Displacement and re-accumulation of centromeric cohesin during transient pre-anaphase centromere splitting. Chromosoma 116, 531–544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Winters T., McNicoll F., and Jessberger R. (2014) Meiotic cohesin STAG3 is required for chromosome axis formation and sister chromatid cohesion. EMBO J. 33, 1256–1270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rudra S., and Skibbens R. V. (2013) Cohesin codes: interpreting chromatin architecture and the many facets of cohesin function. J. Cell Sci. 126, 31–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Murayama Y., and Uhlmann F. (2015) DNA entry into and exit out of the cohesin ring by an interlocking gate mechanism. Cell 163, 1628–1640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Heidinger-Pauli J. M., Unal E., Guacci V., and Koshland D. (2008) The kleisin subunit of cohesin dictates damage-induced cohesion. Mol. Cell 31, 47–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Dorsett D., and Ström L. (2012) The ancient and evolving roles of cohesin in gene expression and DNA repair. Curr. Biol. 22, R240–R250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Chen F., Kamradt M., Mulcahy M., Byun Y., Xu H., McKay M. J., and Cryns V. L. (2002) Caspase proteolysis of the cohesin component RAD21 promotes apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 16775–16781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Pati D., Zhang N., and Plon S. E. (2002) Linking sister chromatid cohesion and apoptosis: role of Rad21. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 8267–8277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Panigrahi A. K., Zhang N., Mao Q., and Pati D. (2011) Calpain-1 cleaves Rad21 to promote sister chromatid separation. Mol. Cell Biol. 31, 4335–4447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. McNicoll F., Stevense M., and Jessberger R. (2013) Cohesin in gametogenesis. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 102, 1–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wood A. J., Severson A. F., and Meyer B. J. (2010) Condensin and cohesin complexity: the expanding repertoire of functions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 391–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. McAleenan A., Clemente-Blanco A., Cordon-Preciado V., Sen N., Esteras M., Jarmuz A., and Aragón L. (2013) Post-replicative repair involves separase-dependent removal of the kleisin subunit of cohesin. Nature 493, 250–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Rao H., Uhlmann F., Nasmyth K., and Varshavsky A. (2001) Degradation of a cohesin subunit by the N-end rule pathway is essential for chromosome stability. Nature 410, 955–959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Marston A. L. (2014) Chromosome segregation in budding yeast: sister chromatid cohesion and related mechanisms. Genetics 196, 31–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sullivan M., Hornig N. C., Porstmann T., and Uhlmann F. (2004) Studies on substrate recognition by the budding yeast separase. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 1191–1196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zhang N., Jiang Y., Mao Q., Demeler B., Tao Y. J., and Pati D. (2013) Characterization of the interaction between the cohesin subunits Rad21 and SA1/2. PLoS One 8, e69458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Miller M. P., Amon A., and Ünal E. (2013) Meiosis I: when chromosomes undergo extreme makeover. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 25, 687–696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kitajima T. S., Miyazaki Y., Yamamoto M., and Watanabe Y. (2003) Rec8 cleavage by separase is required for meiotic nuclear divisions in fission yeast. EMBO J. 22, 5643–5653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Watanabe Y., and Nurse P. (1999) Cohesin Rec8 is required for reductional chromosome segregation at meiosis. Nature 400, 461–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Eijpe M., Offenberg H., Jessberger R., Revenkova E., and Heyting C. (2003) Meiotic cohesin REC8 marks the axial elements of rat synaptonemal complexes before cohesins SMC1-β and SMC3. J. Cell Biol. 160, 657–670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Lee J., Iwai T., Yokota T., and Yamashita M. (2003) Temporally and spatially selective loss of Rec8 protein from meiotic chromosomes during mammalian meiosis. J. Cell Sci. 116, 2781–2790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Lee J., and Hirano T. (2011) RAD21L, a novel cohesin subunit implicated in linking homologous chromosomes in mammalian meiosis. J. Cell Biol. 192, 263–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Petronczki M., Siomos M. F., and Nasmyth K. (2003) Un mènage à quatre: the molecular biology of chromosome segregation in meiosis. Cell 112, 423–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Zickler D., and Kleckner N. (2015) Recombination, pairing, and synapsis of homologs during meiosis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 10.1101/cshperspect.a016626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hess R. A., and Renato de Franca L. (2008) Spermatogenesis and cycle of the seminiferous epithelium. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 636, 1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Hauf S., Waizenegger I. C., and Peters J.-M. (2001) Cohesin cleavage by separase required for anaphase and cytokinesis in human cells. Science 293, 1320–1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kudo N. R., Anger M., Peters A. H., Stemmann O., Theussl H. C., Helmhart W., Kudo H., Heyting C., and Nasmyth K. (2009) Role of cleavage by separase of the Rec8 kleisin subunit of cohesin during mammalian meiosis I. J. Cell Sci. 122, 2686–2698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Kwon Y. T., Xia Z., An J. Y., Tasaki T., Davydov I. V., Seo J. W., Sheng J., Xie Y., and Varshavsky A. (2003) Female lethality and apoptosis of spermatocytes in mice lacking the UBR2 ubiquitin ligase of the N-end rule pathway. Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 8255–8271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Lomelí H., Ramos-Mejía V., Gertsenstein M., Lobe C. G., and Nagy A. (2000) Targeted insertion of Cre recombinase into the TNAP gene: excision in primordial germ cells. Genesis 26, 116–117 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Wang H., Wan H., Li X., Liu W., Chen Q., Wang Y., Yang L., Tang H., Zhang X., Duan E., Zhao X., Gao F., and Li W. (2014) Atg7 is required for acrosome biogenesis during spermatogenesis in mice. Cell Res. 24, 852–869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Hwang C. S., and Varshavsky A. (2008) Regulation of peptide import through phosphorylation of Ubr1, the ubiquitin ligase of the N-end rule pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 19188–19193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Peters A. H., Plug A. W., van Vugt M. J., and de Boer P. (1997) A drying-down technique for the spreading of mammalian meiocytes from the male and female germline. Chromosome Res. 5, 66–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Song Z. H., Yu H. Y., Wang P., Mao G. K., Liu W. X., Li M. N., Wang H. N., Shang Y. L., Liu C., Xu Z. L., Sun Q. Y., and Li W. (2015) Germ cell-specific Atg7 knockout results in primary ovarian insufficiency in female mice. Cell Death Dis. 6, e1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Storlazzi A., Xu L., Cao L., and Kleckner N. (1995) Crossover and noncrossover recombination during meiosis: timing and pathway relationships. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 8512–8526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Rossitto M., Philibert P., Poulat F., and Boizet-Bonhoure B. (2015) Molecular events and signalling pathways of male germ cell differentiation in mouse. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 45, 84–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Ohkura H. (2015) Meiosis: an overview of key differences from mitosis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 10.1101/cshperspect.a015859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Tachibana-Konwalski K., Godwin J., Borsos M., Rattani A., Adams D. J., and Nasmyth K. (2013) Spindle assembly checkpoint of oocytes depends on a kinetochore structure determined by cohesin in meiosis I. Curr. Biol. 23, 2534–2539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Kouznetsova A., Benavente R., Pastink A., and Höög C. (2011) Meiosis in mice without a synaptonemal complex. PLoS One 6, e28255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Yin Y., Lin C., Kim S. T., Roig I., Chen H., Liu L., Veith G. M., Jin R. U., Keeney S., Jasin M., Moley K., Zhou P., and Ma L. (2011) The E3 ubiquitin ligase Cullin 4A regulates meiotic progression in mouse spermatogenesis. Dev. Biol. 356, 51–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. de Boer E., Dietrich A. J., Höög C., Stam P., and Heyting C. (2007) Meiotic interference among MLH1 foci requires neither an intact axial element structure nor full synapsis. J. Cell Sci. 120, 731–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Chapman D. L., and Wolgemuth D. J. (1994) Regulation of M-phase promoting factor activity during development of mouse male germ cells. Dev. Biol. 165, 500–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Varshavsky A. (2005) Ubiquitin fusion technique and related methods. Methods Enzymol. 399, 777–799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Suzuki T., and Varshavsky A. (1999) Degradation signals in the lysine-asparagine sequence space. EMBO J. 18, 6017–6026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Choi W. S., Jeong B.-C., Joo Y. J., Lee M.-R., Kim J., Eck M. J., and Song H. K. (2010) Structural basis for the recognition of N-end rule substrates by the UBR box of ubiquitin ligases. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 1175–1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Matta-Camacho E., Kozlov G., Li F. F., and Gehring K. (2010) Structural basis of substrate recognition and specificity in the N-end rule pathway. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 1182–1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Baker R. T., and Varshavsky A. (1991) Inhibition of the N-end rule pathway in living cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 1090–1094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Gonda D. K., Bachmair A., Wünning I., Tobias J. W., Lane W. S., and Varshavsky A. (1989) Universality and structure of the N-end rule. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 16700–16712 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Xia Z., Webster A., Du F., Piatkov K., Ghislain M., and Varshavsky A. (2008) Substrate-binding sites of UBR1, the ubiquitin ligase of the N-end rule pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 24011–24028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Kwon Y. T., Xia Z., Davydov I. V., Lecker S. H., and Varshavsky A. (2001) Construction and analysis of mouse strains lacking the ubiquitin ligase UBR1 (E3-α) of the N-end rule pathway. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 8007–8021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Zenker M., Mayerle J., Lerch M. M., Tagariello A., Zerres K., Durie P. R., Beier M., Hülskamp G., Guzman C., Rehder H., Beemer F. A., Hamel B., Vanlieferinghen P., Gershoni-Baruch R., Vieira M. W., et al. (2005) Deficiency of UBR1, a ubiquitin ligase of the N-end rule pathway, causes pancreatic dysfunction, malformations and mental retardation (Johanson-Blizzard syndrome). Nat. Genet. 37, 1345–1350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]