Abstract

Neuronal precursor cell-expressed developmentally down-regulated 4 (Nedd4) was the first ubiquitin protein ligase identified to interact with connexin43 (Cx43), and its suppressed expression results in accumulation of gap junction plaques at the plasma membrane. Nedd4-mediated ubiquitination of Cx43 is required to recruit Eps15 and target Cx43 to the endocytic pathway. Although the Cx43 residues that undergo ubiquitination are still unknown, in this study we address other unresolved questions pertaining to the molecular mechanisms mediating the direct interaction between Nedd4 (WW1–3 domains) and Cx43 (carboxyl terminus (CT)). All three WW domains display a similar three antiparallel β-strand structure and interact with the same Cx43CT 283PPXY286 sequence. Although Tyr286 is essential for the interaction, MAPK phosphorylation of the preceding serine residues (Ser(P)279 and Ser(P)282) increases the binding affinity by 2-fold for the WW domains (WW2 > WW3 ≫ WW1). The structure of the WW2·Cx43CT276–289(Ser(P)279, Ser(P)282) complex reveals that coordination of Ser(P)282 with the end of β-strand 3 enables Ser(P)279 to interact with the back face of β-strand 3 (Tyr286 is on the front face) and loop 2, forming a horseshoe-shaped arrangement. The close sequence identity of WW2 with WW1 and WW3 residues that interact with the Cx43CT PPXY motif and Ser(P)279/Ser(P)282 strongly suggests that the significantly lower binding affinity of WW1 is the result of a more rigid structure. This study presents the first structure illustrating how phosphorylation of the Cx43CT domain helps mediate the interaction with a molecular partner involved in gap junction regulation.

Keywords: connexin, intrinsically disordered protein, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), phosphorylation, ubiquitin ligase, Nedd4

Introduction

Gap junction channels serve to directly interconnect the cytoplasm of neighboring cells, allowing the passage of ions, metabolites, and signaling molecules. Gap junction intercellular communication is an important process that mediates electrical impulse propagation, regulation of cell growth, and whole organ development. Gap junction channels are formed by the apposition of connexons from adjacent cells where each connexon is formed by six connexin proteins. Connexins share a similar topology of four transmembrane domains, two extracellular loops, and three cytoplasmic domains (N terminus, cytoplasmic loop, and C terminus (CT)3). Of the 21 human connexins, connexin43 (Cx43) is the most completely characterized isoform in terms of channel gating properties (1), identified phosphorylation sites (2), known protein partners (3), connexon assembly (4), and channel degradation (5–7).

Unlike most membrane proteins, connexins exhibit exceptionally high turnover rates with half-lives ranging from 1.5 to 5 h (8). The initial step leading to degradation, internalization from the plasma membrane, is a complex process because docked connexons are unable to be separated under physiological conditions (9). Consequently, removal from the plasma membrane is directionally regulated as internalization of the channels within one of the coupled cells forms a double membrane macrostructure called an annular gap junction or connexosome (10); clathrin and other endocytic adaptors have been shown to be involved in this process (11–14). Degradation of connexins involves both the lysosomal (endosome or autophagy) and proteasomal pathways (15–17). Implicated in the regulation of these processes are post-translational modifications (18). For example, studies using cultured cells have shown that activation of protein kinase C (PKC) or mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) induces hyperphosphorylation and subsequent degradation of Cx43 (19–21).

Another type of post-translational modification universally implicated in protein degradation is ubiquitination. Ubiquitin is a small molecule of 8.5 kDa that covalently attaches to lysine residues of target proteins to alter their cellular location, affect their activity, modulate protein interactions, or signal for their degradation (22). Laing and Beyer (23) first demonstrated that ubiquitin was involved in connexin degradation. Using a cell line containing a thermolabile E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme, they showed stable Cx43 protein levels upon heat treatment and in the presence of a proteasomal inhibitor. Subsequent studies have determined that the C-terminal domain of Cx43 (Cx43CT) is ubiquitinated (12, 23–25); however, the lysine residues involved are still unknown (Cx43 contains 23 cytoplasmic lysine residues: three in the N terminus, 11 in the cytoplasmic loop, and nine in the CT domain). Of note, however, a proteome-wide survey by mass spectroscopy recently detected in vivo ubiquitination of Cx43 at lysine residues 9 and 303 (26), but the significance remains unclear.

The neuronal precursor cell-expressed developmentally down-regulated 4 (Nedd4) was the first ubiquitin E3 ligase identified to directly interact with Cx43, and its suppression by siRNA results in an accumulation of Cx43 at the membrane (12, 27). Nedd4 was discovered while screening genes down-regulated during development of the central nervous system in embryonic mice but was later found to be ubiquitously expressed across cell types and species (28, 29). Nedd4 contains a catalytic HECT (homologous to the E6-AP carboxyl terminus) domain, three to four WW domains, and a C2 domain. The HECT domain binds to a ubiquitin-conjugated E2 and transfers the ubiquitin moiety from the E2 to the substrate, and the C2 domain mediates the localization of Nedd4 to the plasma membrane. The WW recognition domains, named after the presence of two conserved tryptophan residues, regulate the substrate selection. Rat Nedd4 contains three WW domains, which have been shown to interact with the Cx43CT (27). Found in a wide variety of signaling proteins (30), WW domains are well folded compact polypeptides containing 38–40 amino acids and are divided into five groups according to their binding motif preference. Class I is the largest group and recognizes PPXY motifs where X represents any amino acid. Classes II, III, and V bind PPLP, PXXGMXPP, and PR-rich motifs, respectively. Class IV binds phosphorylated (S/T)P motifs. The Cx43CT binding site for WW2 was identified and defined as a class I motif (PPXY; Cx43 residues 283–286 (27)). This finding was supported by Girão et al. (12) who showed that the Cx43 mutation P283L (LPXY) reduced the binding affinity between Nedd4 and Cx43. Moreover, a subsequent study using a Cx43-ubiquitin chimera with a Y286A mutation was shown to have increased internalization (31). Conversely, the absence of ubiquitin combined with the Y286A mutation led to the accumulation of Cx43 at the membrane and a decreased level of ubiquitination, suggesting the PPXY motif to be critical for Cx43 ubiquitination and internalization (31). However, upon examination of the Cx43CT sequence, two MAPK phosphorylation sites, Ser279 and Ser282, are adjacent to the PPXY motif (279SPMSPPGY286) and if phosphorylated would form a class IV motif (pSPXpSP where pS is phosphoserine). Therefore, Cx43CT presents two different but overlapping WW binding motifs (PPXY and pSPXpSP) that could work cooperatively to increase the binding affinity with Nedd4 or independently to dictate which WW domain binds the Cx43CT. The possibility of Nedd4 also interacting with the class IV motif is supported by the observation that Cx43 MAPK phosphorylation after EGF stimulation increased binding to WW2 and WW3 (27). Additional unresolved questions from these studies were the location and nature of the binding motif on the Cx43CT for the WW1 and WW3 domains as well as the mechanism of differential WW domain binding caused by phosphorylation of the Cx43CT. Therefore, in this study, we used a combination of different biophysical techniques to assess these questions to provide a better understanding of the recognition between Nedd4 and Cx43 and help define the interplay between phosphorylation and ubiquitination in degradation of connexins.

Experimental Procedures

Expression and Purification of Recombinant Proteins and Peptide Synthesis

The rat Cx43CT236–382 polypeptide (15N-labeled) was expressed and purified as described previously (32, 33). The rat Nedd4 WW domains WW1 (Nedd4245–281), WW2 (Nedd4401–437), and WW3 (Nedd4458–494) were cloned into the bacterial expression vector pGEX-KT (GST-tagged; Amersham Biosciences) using standard PCR methods and transformed for overexpression in BL21(DE3) cells (unlabeled, 15N-, or 13C,15N-labeled) (Agilent Technologies). Purification was conducted as described previously for a recombinant GST-tagged protein with the tag being removed by thrombin digestion (32–34). Cx43CT peptides were synthesized by LifeTein (95% purity). Experiments were performed in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or HEPES buffer (10 mm HEPES, 150 mm NaCl, and 3 mm EDTA) at pH 5.8 or 7.4.

Circular Dichroism (CD)

CD experiments were performed on a Jasco J-815 CD spectrometer at 25 °C in the far UV (260–190 nm) or near UV (340–250 nm) with a 0.1-mm-path length quartz cell using a bandwidth of 1 nm, an integration time of 1 s, and a scan rate of 50 nm/min. Each spectrum is the average of five scans. All spectra were corrected by subtracting the solvent spectrum acquired under identical conditions. The protein concentration for each sample was between 0.55 and 2.2 mm in the far UV and between 3 and 9 mm in the near UV. All CD data were processed using the Spectra Analysis function of Jasco Manager Version 2. Thermal unfolding data were collected for each WW domain in the far UV regions (at 227.5 nm for WW1, 229.5 nm for WW2, and 228.0 nm for WW3) at the same concentrations as for the CD experiments (in a 1-cm cell). The temperature was regulated by a Peltier temperature controller. CD data were recorded every 1 °C from 20 to 100 °C after the temperature equilibrated for 5 s at ±0.1 °C from the target temperature. The thermal unfolding temperature was determined by fitting the curve to a Boltzmann sigmoidal equation using a nonlinear square fitting algorithm (GraphPad Prism software).

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Data Acquisition, Assignment, and Structure Calculation

NMR data were acquired at 7 or 25 °C using a 600-MHz Varian INOVA NMR spectrometer outfitted with a cryoprobe. NMR experiments to determine the WW1, WW2, WW3, and WW2·Cx43CT276–289(Ser(P)279, Ser(P)282) peptide backbone sequential and side chain assignments were collected as described previously (33). NMR spectra were processed using NMRPipe (35) and analyzed using NMRView (36). NOE distance constraints for WW1, WW2, and WW2·Cx43CT276–289(Ser(P)279, Ser(P)282) were obtained from 15N NOESY-HSQC and 13C NOESY-HSQC spectra. Hydrogen bonds were identified from temperature dependence experiments and introduced as a pair of distance restraints. Model structures were calculated by simulated annealing using torsion angle dynamics as implemented in the program Crystallography & NMR System (37) and refined with the ARIA 1.2 (Ambiguous Restraints for Iterative Assignment) software (38, 39). In the first ARIA round, manually assigned NOEs (cross-peak volumes) were included for the generation of initial folded structures. The unambiguous and ambiguous NOE restraints derived from ARIA outputs were further analyzed and used as inputs for the next round of calculations. The resulting list of NOE distance restraints was subjected to a final run of structure calculations where 20 structures were calculated using the simulated annealing protocol of ARIA. The 10 best energy-minimized structures were evaluated using PROCHECK-NMR (40) and selected for display and structural analysis. MOLMOL (41) and PyMOL programs were used for structure visualization. The 10 NMR ensemble structures have been deposited in Protein Data Bank under codes 2n8s, 2n8u, and 2n8t for WW1, WW2, and WW2·Cx43CT276–289(Ser(P)279,Ser(P)282), respectively.

Calculating Binding Affinity by NMR

Gradient-enhanced two-dimensional 15N HSQC experiments were used to obtain binding isotherms of the 15N-labeled Nedd4 WW1, WW2, or WW3 domain at a constant concentration (50 μm) in the absence or presence of increasing amounts (50 μm to 2.5 mm) of different unlabeled Cx43CT peptides. Data were acquired with 1024 complex points in the direct dimension and 128 complex points in the indirect dimension. Chemical shift variations were calculated according to the formula Δδ = √((ΔδHN)2 + (ΔδN/5)2)and plotted as a function of peptide concentration. Dissociation constants (KD) were calculated by nonlinear fitting of the titration curves using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) and averaging at least five curves.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)

Heat produced by the binding of Cx43CT276–289 peptide phosphorylated (Ser(P)279, Ser(P)282) or non-phosphorylated with each of the Nedd4 WW domains was measured by ITC using the MicroCal iTC200 isothermal titration calorimeter from Malvern (Worcestershire, UK). All proteins were equilibrated in 1× PBS at pH 7.4 by overnight dialysis. ITC binding isotherms were collected at 25 °C by injecting 20 × 2 μl of peptide (1.7–7.9 mm) into a solution of each of the WW domains (90–790 μm), representing a 1:10–1:30 molar ratio. The heat from each injection was measured by integrating the area of the injection peak, corrected for the background heat produced by the dilution of the peptide into the buffer, and plotted as a function of the WW domain/peptide molar ratio. KD values were calculated by fitting the titration curves according to a single binding site model with Origin 7 software with ITC add-ons supplied by Malvern.

Results

Structural Characterization of the Nedd4 WW Domains

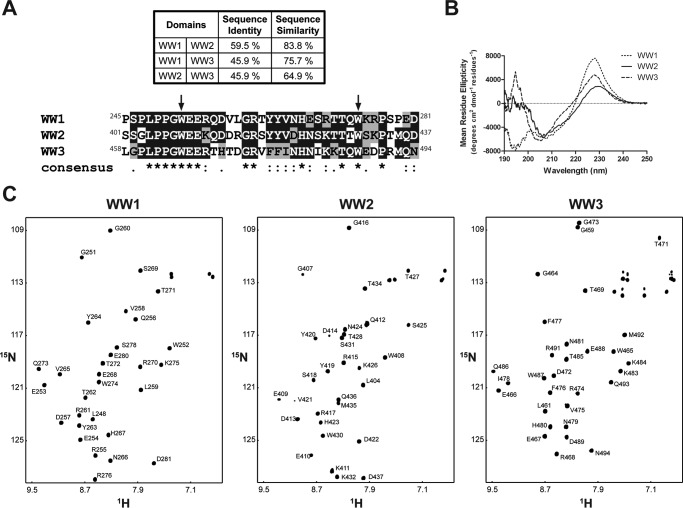

Leykauf et al. (27) observed differential binding between the three Nedd4 WW domains (Fig. 1A) and the Cx43CT regardless of the Cx43CT phosphorylation state. Possible explanations for these observations include differences between the WW domains in their structure, dynamics, and/or residues at the binding interface. Therefore, CD spectra of the WW1–3 domains in the far UV (190–250 nm) were collected to detect any difference in their overall secondary structure (Fig. 1B). The far UV spectrum for each WW domain is consistent with that of a protein containing β-sheet structure. The minimum usually observed around 217 nm for pure β-sheet is shifted to ∼205 nm due to a significant content of random coil structure (42% for each domain) as calculated by DICHROWEB (42, 43). Consistent with other members of the WW domain family, the two conserved tryptophan residues cause a positive ellipticity around 228 nm (44, 45). Interestingly, WW1 also has a negative peak around 196 nm, which is normally positive in β-sheet structures, as observed for the WW2 and WW3 domains. The 196 nm peak is the result of the Π → Π* transition (i.e. light absorbed), which is dominated by the backbone carbonyl Π bond and is also affected by the involvement of the nitrogen in the Π orbitals. All peaks observed in CD rely on the intensity and energy of transitions that depend on the φ and ψ angles; therefore, the data suggest that the WW1 structure could be slightly different from the WW2 and WW3 structures. Moreover, the negative peak around 196 nm for WW1 could be caused by a number of amino acid side chains that have transitions in the peptide region (i.e. sequence-specific differences between the WW domains).

FIGURE 1.

Secondary structural analysis of the Nedd4 WW domains. A, sequence identity and similarity between the three Nedd4 WW domains as well as the sequence alignment of the three rat Nedd4 WW domains. Fully conserved residues are highlighted in black, and conserved residues are highlighted in gray. On the consensus line, stars (*), colons (:), and periods (.) represent fully conserved residues, residues with strongly similar properties, and semiconserved residues among the three domains, respectively. B, CD spectra of each Nedd4 WW domain in the far UV in 1× PBS (pH 7.5). C, 15N HSQC spectra of each Nedd4 WW domain in 1× PBS (pH 7.5). Each amide cross-peak is labeled.

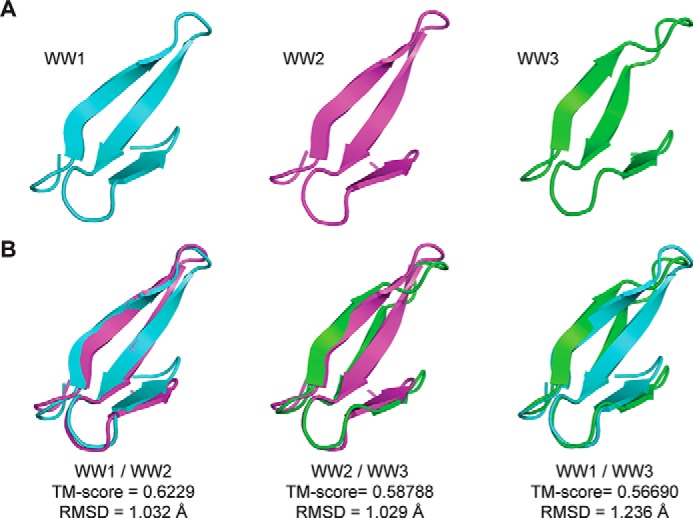

To further characterize the structural differences between the WW domains, NMR was used to solve the structures of the WW1 and WW2 domains. The NMR solution structure of WW3 has already been solved albeit in complex with a small peptide (46). All 1H, 15N, and 13C backbone resonances and most side chain and aromatic groups of the WW1 and WW2 domains (97 and 95% of the expected resonances, respectively) were assigned in 1× PBS (pH 7.4) at 25 °C (Fig. 1C). The chemical shift data were deposited into the BioMagResBank database under accession numbers 25864 (WW1) and 25866 (WW2). Of note, most backbone and side chain resonances were assigned for the WW3 domain alone (Fig. 1C; chemical shift data were deposited into the BioMagResBank database under accession number 26698) to calculate the binding affinity with different Cx43CT peptides. The solution structures of the WW1 and WW2 (Fig. 2A, left and center, respectively) domains display a bundle of three antiparallel β-strands, resembling that of WW3 (Fig. 2A, right; from Ref. 46). The coordinates were deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession codes 2n8s (WW1) and 2n8u (WW2). The template modeling score that focuses on evaluating the topology fold similarity was above 0.5 for all WW pairings (Fig. 2B) in agreement with a very comparable fold (47). Moreover, the root mean square deviation (r.m.s.d.) value observed between the WW domains is ∼1 Å, which is indicative of a good structural superposition. WW1 has a larger number of hydrogen bonds and NOE restraints compared with WW2 (Table 1), suggesting a more rigid structure. The NMR data are supported by the near UV CD spectra of the WW domains (250–340 nm), which generate a fingerprint of the chiral environment of aromatic residues, thus providing a tool to monitor their local conformation (Fig. 3A). The three WW domains have a similar tertiary structure based on the overall similarity in shape of the spectra between 250 and 290 nm. One difference is that the WW1 signal is significantly higher in intensity (caused by closer aromatic side chain packing) as compared with the WW2 and WW3 domains, suggesting a more rigid structure (48).

FIGURE 2.

Solution structure of the Nedd4 WW domains. A, structure of each Nedd4 WW domain determined by NMR. The previously published WW3 structure is presented for comparison with the WW1 and WW2 domains (46). B, overlay of the Nedd4 WW domain structures. The template modeling score (TM-score) and the r.m.s.d. values are indicated.

TABLE 1.

Structural statistics of the 10 lowest energy structures of the rat Nedd4 WW1 and WW2 domains

| WW1 (Pro245–Asp281) | WW2 (Ser401–Asp437) | |

|---|---|---|

| Conformational restraints | ||

| NOE distance restraints | ||

| Total | 1202 | 801 |

| Intraresidue (|i − j| = 0) | 564 | 328 |

| Sequential (|i − j| = 1) | 254 | 154 |

| Medium range (2 ≤ |i − j| < 4) | 121 | 92 |

| Long range (|i − j| ≥ 5) | 263 | 227 |

| Backbone hydrogen bonds | 12 | 6 |

| Residual violations (average number per residue) | ||

| Distance restraints >0.3 Å | 0 | 0 |

| Distance restraints >0.5 Å | 0 | 0 |

| Energiesa (kcal·mol−1) | ||

| NOE | 8.3 ± 2 | 3.5 ± 1 |

| van der Waals | −310 ± 5 | −273 ± 16 |

| Electrostatic | −1430 ± 33 | −1499 ± 77 |

| Ramachandran plotb (%) | ||

| Most favored regions | 89.7 | 82.9 |

| Additional allowed regions | 9.3 | 15.8 |

| Generously allowed regions | 1.0 | 1.3 |

| Average r.m.s.d.c | ||

| Backbone (Å) | 1.61 ± 0.57 | 2.73 ± 0.49 |

| All non-hydrogens (Å) | 1.59 ± 0.44 | 2.78 ± 0.44 |

a Calculated with the standard parameters of ARIA.

b Ramachandran analysis was performed using PROCHECK.

c Fit on secondary structures.

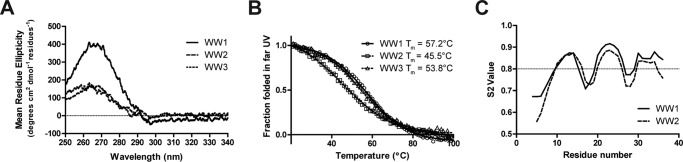

FIGURE 3.

Tertiary structure, thermal stability, and flexibility of the Nedd4 WW domains. A, CD spectra of each Nedd4 WW domain in the near UV in 1× PBS (pH 7.5). B, thermal stability of each Nedd4 WW domain in the far UV collected at their positive maximum. Melting temperature (Tm) values are indicated. C, plot of order parameter S2 obtained from the random coil index server as a function of WW1 (solid line) and WW2 (dashed line) residue number.

To confirm this difference in dynamics, CD was also used to evaluate the thermal stability of the three WW domains (Fig. 3B). The change in secondary structure was assessed by following the maximum ellipticity wavelength signal for each WW domain (WW1, 227.5 nm; WW2, 229.5 nm; and WW3, 228.0 nm) as a function of temperature. The three WW domains present thermal stabilities of 45.5 (WW2), 53.8 (WW3), and 57.2 °C (WW1) with the WW1 domain being the most stable (i.e. higher temperature to unfold). Finally, protein flexibility was predicted using the random coil index method, which quantitatively estimates backbone root mean square fluctuations of structural ensembles and order parameters using only chemical shifts (49). In Fig. 3C, the model-free order parameter S2 is provided as a function of residue number. The order parameter S2 describes the amount of local mobility with S2 = 1 for no local motion and S2 = 0 for completely unrestricted local motion of the NH vectors (50). Although the local motion in β-strand 1 is similar between the WW1 and WW2 domains, the WW1 domain is more rigid in β-strands 2 and 3. Altogether, the structural data identified differences in the dynamic properties and thermostability between the Nedd4 WW domains. Although this may account for the different binding affinities with the Cx43CT (27), another possibility is that the sequence-specific residues in the binding pocket differ. To address this possibility, we next determined the residues involved in the Cx43CT interaction with the WW1 and WW3 domains.

Location of the Cx43CT Interaction with the Nedd4 WW1 and WW3 Domains

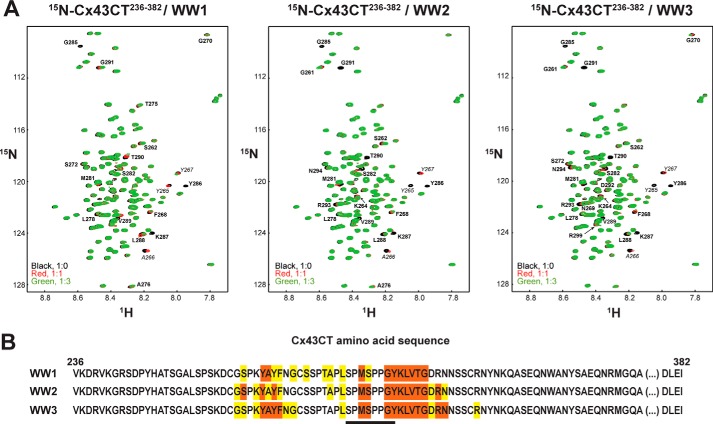

Although all three WW domains of Nedd4 were shown to interact with the Cx43CT (27), only the area of interaction for WW2 has been identified (within residues Cys271–Leu288; contains PPXY motif), and a different Cx43CT region and binding motif were suggested for WW1 and WW3. To determine the portion of Cx43CT interacting with WW1 and WW3, 15N HSQC spectra of Cx43CT236–382 were collected in the presence of various concentrations of each WW domain (Fig. 4A). A summary of the residues affected by each WW domain is displayed in Fig. 4B. The three Nedd4 WW domains strongly affect the Cx43CT (peaks broaden beyond detection) over an area encompassing Met281–Gly291, which includes the PPXY (283PPGY286) motif. A second area between Gly261 and Gly270 (peaks shift), which is commonly affected by protein partners binding anywhere along the Cx43CT domain (51), was weakly affected by the interaction with the WW domains. The Met281–Gly291 sequence also overlaps with a potential Class IV WW domain binding motif pSPXpSP (279pSPMpSP283), suggesting that phosphorylation of the Cx43CT could influence the binding affinity with the WW domains.

FIGURE 4.

15N HSQC spectra of Cx43CT236–382 in the presence of the Nedd4 WW domains. A, control spectrum (Cx43CT236–382 alone; black) in 1× PBS (pH 7.5) overlaid with spectra obtained when both Cx43CT236–382 and the Nedd4 WW1, WW2, or WW3 domain were present in a 1:1 (red) and 1:3 (green) molar ratio. Cx43CT236–382 residues affected upon binding are labeled. B, summary of the Cx43CT236–382 residues affected by each Nedd4 WW domain (orange, peaks broaden beyond detection; yellow, peaks shift). Residues involved in the interaction (including MAPK phosphorylated Ser279 and Ser282 and Tyr286) are underlined.

Influence of Cx43CT Phosphorylation on the Interaction with Nedd4 WW1–3 Domains

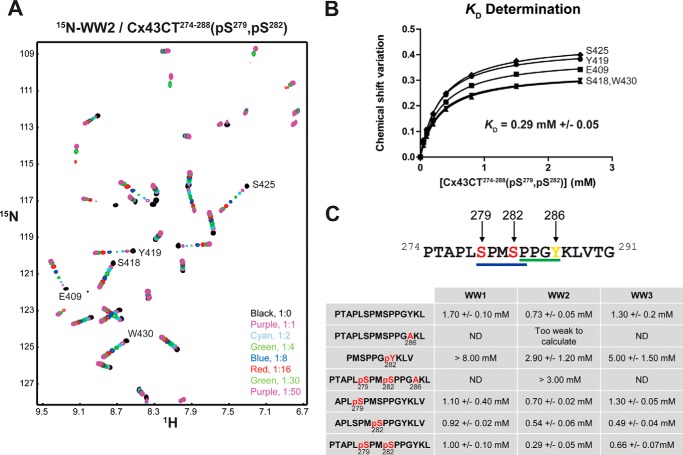

Cx43CT phosphorylation upon MAPK activation (EGF treatment) was shown to increase the amount of Cx43 pulled down by Nedd4 GST-WW domains, notably WW2 and WW3 (27). MAPK has been identified to phosphorylate Cx43CT residues Ser255, Ser262, Ser279, and Ser282 (52). Cx43 phosphorylation at Ser279 and Ser282 showed weak binding to WW2 and no binding to WW1 and WW3, suggesting that phosphorylated residues other than Ser279 and Ser282 increased the binding affinity between Cx43CT and the WW domains (27). However, because all three Nedd4 WW domains interacted with the same Cx43CT residues that contain the PPXY motif and overlap with residues of the pSPXpSP motif, Cx43CT peptides were designed to study the impact of the two motifs and the effect of Cx43CT phosphorylation on the binding affinity with the WW domains.

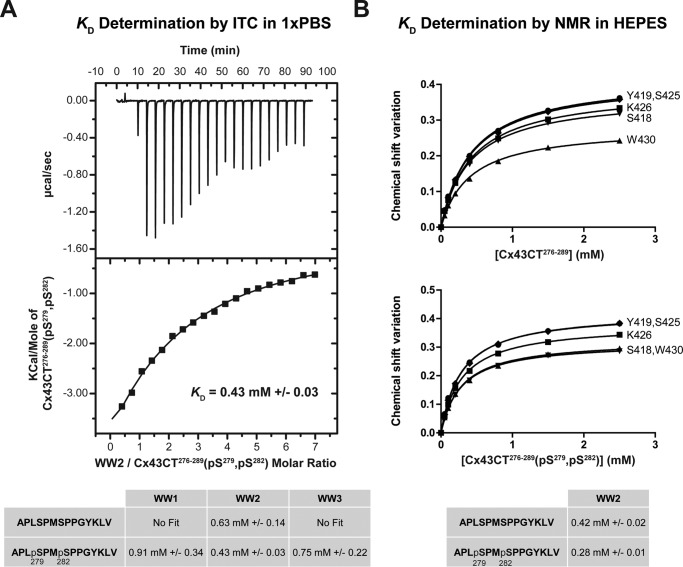

The KD values were calculated for each WW domain with the Cx43CT peptides by holding the concentration of the 15N-labeled WW domain constant (50 μm) and titrating the unlabeled CT peptides from 50 μm to 2.5 mm (Fig. 5A). The changes in chemical shift of at least 5 residues affected as a result of the increasing Cx43CT peptide concentrations were then fitted according to the nonlinear least square method to estimate the binding constant (Fig. 5B). For the control peptide (no phosphorylation; PPXY motif), WW2 exhibits the highest binding affinity (KD = 0.73 ± 0.05 mm (mean ± S.D.)) followed by WW3 and WW1 (1.30 ± 0.20 and 1.70 ± 0.10 mm, respectively) (Fig. 5C). Any modification of the critical PPXY motif residue Tyr286 (mutation, Y286A; phosphorylation, Tyr(P)286) with or without phosphorylation at Ser279 and Ser282 significantly reduced the binding affinity with all the WW domains. Next, the peptides (PPXY motif) were differentially phosphorylated to determine the influence of the pSPXpSP (Ser(P)279 and Ser(P)282) motif on the binding affinity with the WW domains. Ser(P)279 alone had no influence on binding the WW domains. Ser(P)282 significantly increased the binding affinity (WW2 ∼ WW3 ≫ WW1); however, phosphorylation at both Ser(P)282 and Ser(P)279 further increased the binding affinity for only WW2. These binding affinities were independently confirmed using a different biophysical technique (ITC; Fig. 6A) and a phosphate-independent buffer (HEPES; Fig. 6B). Altogether, the data indicate that the Cx43CT PPXY motif is critical for binding the WW domains, whereas the pSPXpSP motif modulates this interaction.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of phosphorylation on the interaction of Nedd4 WW domains with Cx43CT. A, example of an NMR titration experiment. 15N HSQC spectra of Nedd4 WW2 alone (black) and in the presence of various molar ratios of Cx43CT274–288(Ser(P)279, Ser(P)282) (indicated in the lower right corner) in 1× PBS at pH 7.5 were collected. B, KD (±S.D.) for the [15N]WW2/Cx43CT274–288(Ser(P)279, Ser(P)282) interaction estimated by fitting the changes in chemical shift (according to the formula Δσ = √((ΔδHN)2 + (ΔδN/5))2) for the indicated WW2 residues as a function of Cx43CT274–288(Ser(P)279, Ser(P)282) concentration. C, summary of the KD (±S.D.) obtained in the presence of differentially phosphorylated Cx43CT peptides.

FIGURE 6.

Confirming the binding affinity between the Nedd4 WW2 domain and the Cx43CT276–289 peptide. A, different experimental technique, ITC. The ITC profile of the Cx43CT276–289(Ser(P)279, Ser(P)282) interaction with the Nedd4 WW2 domain was obtained. The top panel shows the heat produced upon injection of Cx43CT276–289(Ser(P)279, Ser(P)282) peptide, and the lower panel shows the binding curve after integration of the peaks, corrected for the peptide dilution and normalized by the moles of Cx43CT276–289(Ser(P)279, Ser(P)282) added. The table contains a summary of the KD (±S.D.) obtained for each Nedd4 WW domain in the presence of diphosphorylated (Ser(P)279, Ser(P)282) and non-phosphorylated Cx43CT276–289 peptides. B, different buffer, HEPES. The NMR titration experiment (15N HSQC) was performed using Nedd4 WW2 in the presence of different concentrations of non-phosphorylated Cx43CT276–289 or diphosphorylated (Ser(P)279, Ser(P)282) peptides in HEPES at pH 7.5. The table contains a summary of the obtained KD (±S.D.) values.

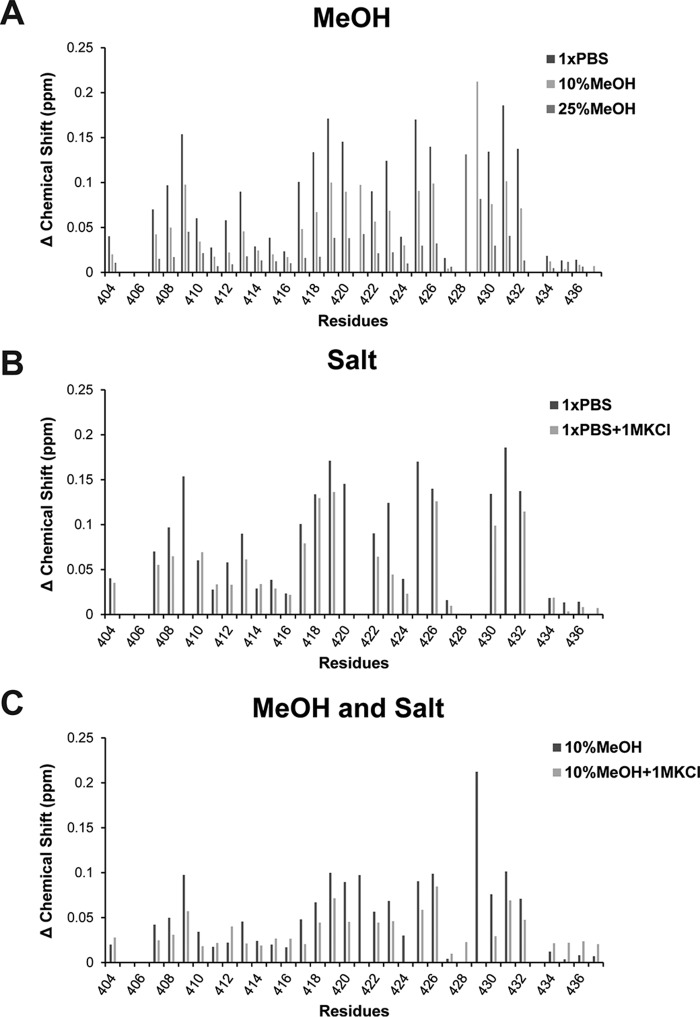

The importance of the PPXY motif was also evident when solution conditions (+MeOH or +KCl) were tested to identify the main driving force (hydrophobic or electrostatic) mediating the WW/Cx43CT domain interaction (Fig. 7). [15N]WW2 and the Cx43CT peptide (Ser(P)279, Ser(P)282; 1:4 molar ratio) were collected in the presence of 10 or 25% MeOH, 1 m KCl, or both 10% MeOH and 1 m KCl. Although addition of 10% MeOH clearly reduced the shifts observed upon addition of the CT peptide compared with the shifts in 1× PBS (i.e. reduced the binding affinity), the addition of high salt (1 m KCl) only had a minor impact on the interaction. When 1 m KCl was added to a solution already containing 10% MeOH, the interaction further decreased in comparison with 10% MeOH alone. The data suggest that the dominant force mediating the Cx43CT and WW domain interaction is hydrophobic with a contribution from electrostatic interactions, most likely involving Tyr286 and Ser(P)279/Ser(P)282, respectively.

FIGURE 7.

Main driving force mediating the interaction of Nedd4 WW2 domains with Cx43CT274–288(Ser(P)279, Ser(P)282). 15N HSQC spectra of the Nedd4 WW2 domain in complex with Cx43CT274–288(Ser(P)279, Ser(P)282) (1:4 ratio) were collected in the presence of 10 and 25% MeOH (A), 1 m KCl (B), or 10% MeOH + 1 m KCl (C). Represented are the chemical shift variations for each residue plotted according to the formula Δσ = √((ΔδHN)2 + (ΔδN/5))2.

Mechanism of Cx43CT Phosphorylation-based Increase in the WW Binding Affinity

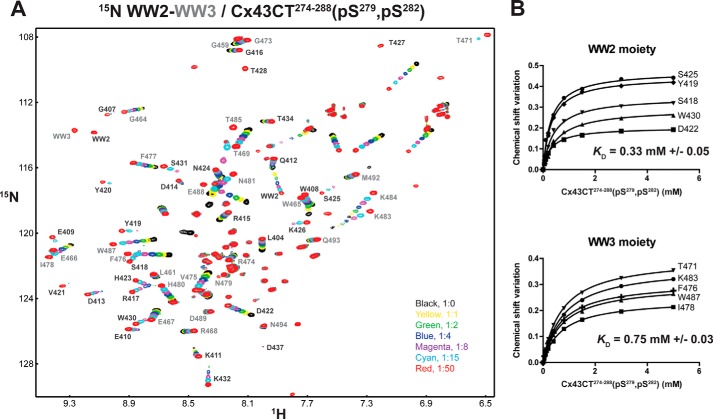

The WW1 and WW2 domains of Smurf1 or YAP (Yes kinase-associated protein) can simultaneously bind a peptide from Smad1 that contains both a PPXY and a pSP motif (53). Because the Nedd4 WW2 and WW3 domains are in close proximity (21 amino acids apart), the possibility exists that the PPXY and pSPXpSP motifs are meant to interact simultaneously with different WW domains in a cooperative manor. With the aid of the individual WW2 and WW3 NMR data, most of the amide peaks were assigned in the 15N HSQC belonging to the WW2-WW3 tandem construct (Nedd4 Ser401–Asn494; Fig. 8A). 15N HSQC spectra of WW2-WW3 in the presence of various concentrations of a Cx43CT peptide containing the PPXY and pSPXpSP (Ser(P)279, Ser(P)282) motifs were collected. The amount of Cx43CT peptide needed to reach saturation with WW2-WW3 was doubled compared with the individual WW domains. After calculating the KD for each WW domain, the values were found to be consistent with the binding affinity obtained when the WW domains were alone (Fig. 8B), suggesting a 1:2 binding ratio and no cooperative binding.

FIGURE 8.

15N HSQC spectra of the Nedd4 WW2-WW3 tandem construct in the presence of Cx43CT274–288(Ser(P)279, Ser(P)282). A, 15N HSQC spectra of the Nedd4 WW2-WW3 (Ser401–Asn494) tandem construct alone (black) and in the presence of various molar ratios of Cx43CT274–288(Ser(P)279, Ser(P)282) (indicated in the lower right corner) in 1× PBS (pH 7.5). Each amide cross-peak belonging to the WW2 and WW3 moiety is labeled in black and gray, respectively. B, KD (±S.D.) values for the interaction of Cx43CT274–288(Ser(P)279, Ser(P)282) with each Nedd4 WW domain were estimated by fitting the changes in chemical shift for the indicated WW2 and WW3 residues as a function of Cx43CT274–288(Ser(P)279, Ser(P)282) concentration.

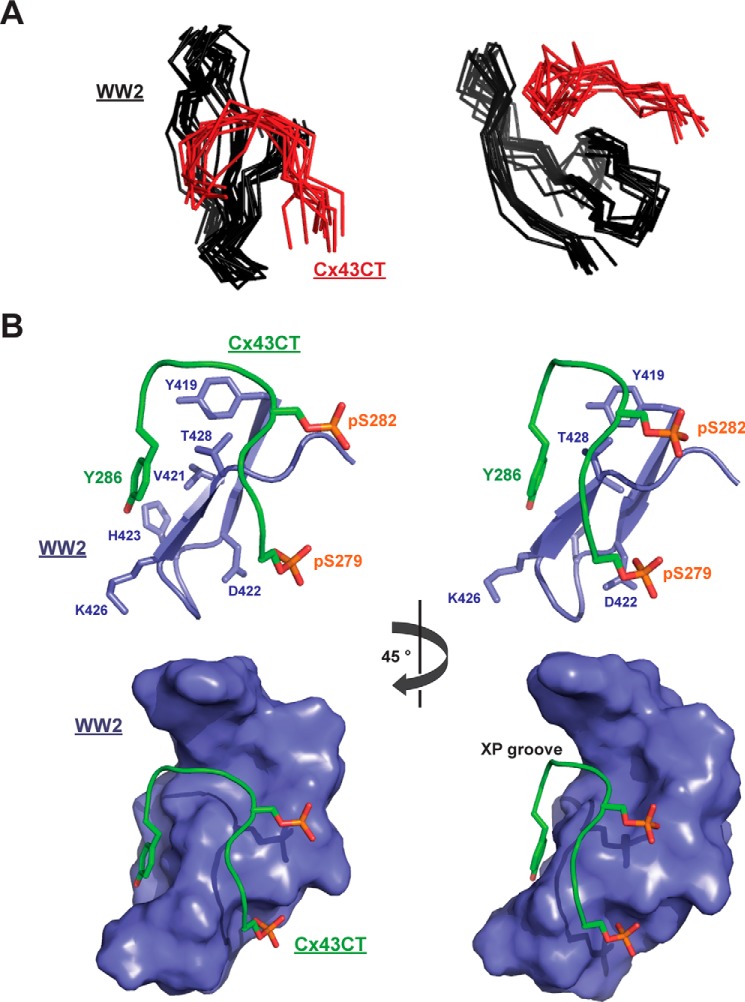

To understand the structural basis for the WW2 domain to have the highest binding affinity for the Cx43CT and the role of phosphorylation in this interaction, we solved the solution structure of the WW2 domain in the presence of the Cx43CT Ser(P)279/Ser(P)282 peptide (Ala276–Val289) by NMR. Structure calculation by torsion angle dynamics followed with refinement by simulated annealing and energy minimization led to the family of structures shown in Fig. 9A. The structures were superimposed on the basis of the backbone coordinates from the WW2 residues Gly407–Lys432, which excluded the disordered N and C termini (Ser401–Gly407 and Pro433–Asp437). The WW2 and Cx43CT peptide backbone r.m.s.d. values for this alignment were 0.87 ± 0.21 and 1.94 ± 0.61 Å, respectively. The structural models fit the NMR data well with no violations of experimental distance restraints greater than 0.29 Å. Structural statistics are presented in Table 2. The overall structure of the WW2 domain displays a bundle of three antiparallel β-strands similar to the WW2 domain alone (r.m.s.d., 1.24 Å; data not shown). The overall structure of the Cx43CT peptide displays a horseshoe-shaped arrangement. The critical Cx43 tyrosine residue (Tyr286) anchors to the side chains of WW2 residues Tyr419, Val421, His423, Lys426, Thr427, and Thr428; they comprise the front face of the WW2 β2-loop-β3 structure (Fig. 9B, top). Pro283 and Pro284 form a short polyproline II helix that recognizes a pocket known as the XP groove formed by the second conserved tryptophan (Trp430) and the highly conserved tyrosine (Tyr419) in the WW domain (54). Phosphorylation of Cx43 residue Ser(P)282 enables close contacts (≤5 Å) with the backbone atoms from WW2 residues Thr428, Thr429, and Trp430 (end of β3). Phosphorylation of Cx43 residue Ser(P)279 facilitates close contacts (≤5 Å) with the side chain atoms from WW2 residues Thr427 and Ser425 (back face of β3). Together, the contacts formed by phosphorylation cause the Cx43CT to form a horseshoe-shaped arrangement that fits into a groove formed by the Nedd4 WW2 domain (Fig. 9B, bottom).

FIGURE 9.

Solution structure of the Nedd4 WW2 domain in the presence of the Cx43CT276–289(Ser(P)279, Ser(P)282) peptide. A, two different views of the 10 lowest energy structures of the WW2 domain (black) in complex with the Cx43CT276–289(Ser(P)279, Ser(P)282) peptide (red) overlaid according to the WW2 backbone atoms. Only WW2 residues Gly408–Lys432, excluding the disordered N- and C-terminal residues, are shown. B, top panel, shows two close-up views, 45° apart according to the y axis, of the binding site between the Nedd4 WW2 domain (residues Tyr419–Ser431 are represented; lilac) and the Cx43CT276–289(Ser(P)279, Ser(P)282) peptide (residues Ser279–Tyr286 are represented; green). Residues directly involved in the interaction are labeled, and their side chains are shown. The bottom panel is the surface representation with the same illustrated residues and angles as the top panel (WW2 residues Tyr408–Lys432) showing the fitting of the peptide into the XP groove.

TABLE 2.

Structural statistics of the 10 lowest energy structures of the Cx43CT276–289(Ser(P)279, Ser(P)282)·rat Nedd4 WW2 domain complex

| NOE distance restraints | |

| Total | 1030 |

| Intraresidue (|i − j| = 0) | 526 |

| Sequential (|i − j| = 1) | 178 |

| Medium range (2 ≤ |i − j| < 4) | 89 |

| Long range (|i − j| ≥ 5) | 236 |

| Backbone hydrogen bonds | 12 |

| Residual violations (average number per residue) | |

| Distance restraints >0.3 Å | 0.1 |

| Distance restraints >0.5 Å | 0 |

| Energiesa (kcal·mol−1) | |

| NOE | 11 ± 6 |

| van der Waals | −360 ± 110 |

| Electrostatic | −1948 ± 166 |

| Ramachandran plotb (%) | |

| Most favored regions | 68.0 |

| Additional allowed regions | 28.3 |

| Generously allowed regions | 2.5 |

| Disallowed regions | 1.2 |

| Average r.m.s.d.c | |

| Nedd4 WW2 domain (Gly403–Lys432) | |

| Backbone (Å) | 0.87 ± 0.21 |

| All non-hydrogens (Å) | 2.01 ± 0.34 |

| Cx43CT (Ala276–Val289) | |

| Backbone (Å) | 1.94 ± 0.61 |

| All non-hydrogens (Å) | 2.59 ± 0.67 |

a Calculated with the standard parameters of ARIA.

b Ramachandran analysis was performed using PROCHECK.

c Fit on secondary structures.

Discussion

The studies of Leyauf et al. (27) and Girão et al. (12) helped define the biological importance of Nedd4 in the regulation of gap junction intercellular communication. Nedd4 was the first ubiquitin protein ligase identified to interact with Cx43, and its suppressed expression results in accumulation of gap junction plaques at the plasma membrane (27). Nedd4-mediated ubiquitination of Cx43 is required to recruit Eps15 and target Cx43 to the endocytic pathway (12). Although the Cx43 residues that undergo ubiquitination are still unknown, in this study, we address other unresolved questions pertaining to the molecular mechanisms mediating the direct interaction between Nedd4 and Cx43.

Where Do the Nedd4 WW1 and WW3 Domains Interact with the Cx43CT?

Leykauf et al. (27) demonstrated that all three Nedd4 WW domains interact with Cx43 in a pulldown assay. However, surface plasmon resonance experiments only detected a direct interaction between WW2 and a PPXY motif containing Cx43CT peptide (Cys271–Leu288). The conclusion was that WW1 and WW3 were interacting with a different Cx43CT domain (27). The sequence similarity between all three WW domains is between 60 and 80% (Fig. 1A), suggesting a common overall fold and mechanism of binding with the Cx43CT. The solution structure of the three rat Nedd4 WW domains confirmed a similar fold (r.m.s.d., 1.03–1.24 Å) consisting of three antiparallel β-strands that are stabilized by a hydrophobic cluster formed in part by conserved Trp (position +10) and Pro (position +25) residues. Using the full-length Cx43CT domain, NMR titration experiment in the presence of the Nedd4 WW domains identified that WW1 and WW3 bind to the same Cx43CT PPXY (Pro283–Tyr286) motif as WW2. The difference between the Nedd4 WW domains is that WW2 has a higher binding affinity (0.73 ± 0.05 mm) than WW3 (1.3 ± 0.02 mm) or WW1 (1.7 ± 0.1 mm). The close proximity of Cx43CT residues Ser279 and Ser282 to the PPXY motif suggests that phosphorylation by MAPK would affect the binding affinity of Cx43CT for the Nedd4 WW domains (55, 56).

Does MAPK Phosphorylation of the Cx43CT Affect the Interaction with the Nedd4 WW1–3 Domains?

NMR titration experiments using the three Nedd4 WW domains and different Cx43CT phosphopeptides revealed that Ser(P)282 had the most dramatic effect, increasing the Cx43CT binding affinity ∼2-fold for each of the WW domains (KD, WW2 ∼ WW3 ≫ WW1). Conversely, phosphorylation of Cx43CT residue Ser279 alone had no effect on the binding affinity. Only WW2 utilized phosphorylation of both Cx43CT residues Ser279 and Ser282, which also had the highest binding affinity (KD, WW2 > WW3 ≫ WW1). The close sequence identity between the WW1–3 residues that interact with the Cx43CT PPXY motif and Ser(P) (Fig. 1A) strongly suggest that the significant difference in binding affinity of WW1 is the result of a more rigid structure. The NMR data identified that the increased rigidity for WW1 is localized to β-strands 2 and 3, which are the same β-strands involved in the direct interaction with the Cx43CT. Consistent with previous studies, Cx43CT residue Tyr286 is necessary for the direct interaction with the Nedd4 WW domains (31). NMR titration data also revealed that phosphorylation of Tyr286 would inhibit the interaction with the Nedd4 WW domains. We are unclear to as why the WW1 and WW3 domains did not interact with biotinylated Cx43CT peptides attached to the streptavidin surface of the sensor chip in the Leykauf et al. (27) study. Additionally, the binding affinities for both the Cx43CT control (1.1 versus 730 μm) and the Ser(P)279/Ser(P)282 phosphopeptide (0.6 versus 290 μm) with WW2 were different between our studies. This large difference led us to 1) ensure this was not a buffer-dependent effect (HEPES versus PBS) and 2) use ITC as a third, independent measurement of the binding affinity. ITC data for the three Nedd4 WW domains with the Cx43CT control (e.g. WW2, 630 ± 140 μm) and the Ser(P)279/Ser(P)282 phosphopeptide (e.g. WW2, 430 ± 30 μm) were similar to the NMR titration data. One possible explanation for these differences is that surface plasmon resonance requires immobilization of one of the binding partners onto a surface, whereas NMR and ITC do not. Another potential explanation is that biosensor experiments have the potential of artifacts caused by mass transport, nonspecific binding, and avidity effects that could alter the apparent binding constants (57, 58). Of note, when using surface plasmon resonance, our laboratory has experienced nonspecific binding caused by the intrinsically disordered Cx43CT as well as higher binding affinities for protein partners when compared with well established values in the literature.

Pulldown experiments were performed by Leykauf et al. (27) using GST-tagged WW domains along with control and EGF-treated (leads to phosphorylation of Cx43CT residues Ser279 and Ser282) cell lysate. Analysis with a polyclonal and phosphospecific antibody (Ser(P)279 and Ser(P)282) to the Cx43CT led to the following conclusions. 1) The WW2 domain mainly interacted with the non-phosphorylated form of Cx43, 2) phosphorylation of Cx43CT residues Ser279 and Ser282 led to the inhibition of the interaction between Cx43 and Nedd4 domain WW3, and 3) phosphorylation of Cx43CT residues other than Ser279 and Ser282 appears to be significant for the Cx43 interaction with WW3. Of note, also from the Leykauf et al. (27) study, the immunoprecipitation experiment showed that Nedd4 interacted only with the Cx43 P1 and P2 isoforms in untreated WB-F344 cells, whereas in the pulldown experiment with the same cells, Nedd4 interacted predominately with the Cx43 P0 isoform. These findings are not what we would predict based upon the three Nedd4 WW domains interacting with the same Cx43CT residues, the order of binding affinity (WW2 > WW3 ≫WW1), Cx43CT phosphorylation enhancing the binding affinity in a similar manner (WW2 > WW3 ≫ WW1), and the WW2·Cx43CT (Ser(P)279, Ser(P)282) structure. One possibility is that our studies involve the use of protein fragments in solution, conditions likely different from the microenvironment of the CT when integrated in a gap junction plaque. However, several studies have shown that, even when not fused with the pore-forming region, the Cx43CT domain retains the biochemical and functional properties consistent with those found in a gap junction plaque (e.g. Refs. 59–63). These conclusions were formulated based upon the belief that the P0 Cx43 isoform is completely non-phosphorylated. Our laboratory and others have identified that the P0 isoform can also contain phosphorylated Cx43 (64, 65). Interestingly, we have identified that MAPK phosphorylation of Cx43 at residue Ser282 alone results in Cx43 migration at P0. This finding, along with the higher binding affinity for Cx43 when Ser282 is phosphorylated as compared with no phosphorylation, could explain why the Cx43 P0 isoform was the dominate isoform pulled down by the WW domains in the Leykauf et al. (27) study. This would also explain why the MAPK phosphospecific antibody (Ser(P)279 and Ser(P)282-specific) did not recognize WW1 and WW3 and barely WW2 if the predominant Cx43 isoform in the pulldown experiment contained phosphorylation at Ser282 only. This illustrates the difficulty with interpreting absolute Cx43 phosphorylation levels with the different migrating isoforms.

Why Does MAPK Phosphorylation of Cx43 Increase the Binding Affinity for the Nedd4 WW Domains?

To the best of our knowledge, the Cx43CT sequence is unique in that a critical Class I motif (PPXY) is aided by multiple, preceding Ser(P) residues to achieve a higher binding affinity with a WW2 domain. A previous study has identified that threonine residues in the immediate vicinity (one before and one after) of the PPXY motif increase the binding affinity for Nedd4 2–3-fold (66). The closest structure comparisons of Cx43CT and Nedd4 can be made with the Nedd4L (66% identity) and Pin1 (38% identity) WW domains bound to the phosphorylated PPXY motif (178EpTPPPGYLSEDG189 where pT is phosphothreonine) of Smad3 (53). The PPGY motif from both Cx43CT and Smad3 interact in an almost identical manner with their WW2 domains and form a short polyproline II helix. For Smad3, the extra Pro preceding the PPXY motif enables Thr(P)179 to coordinate with arginine side chains (Arg18 and Arg21) in β-strand 1 and loop 1 of the Pin1 WW domain. This differs from the coordination of this phosphate group with the side chains of Lys378 and Arg380 in β-strands 2 and 3 of the Nedd4L WW domain. Sequence alignment reveals that the position of Arg21 (Pin1) and Lys378 (Nedd4L) is Asp414 for the Nedd4 WW2 domain, which would not favor an interaction with a negatively charged phosphate. The Cx43CT (Ser(P)279, Ser(P)282)·Nedd4 WW2 domain complex structure reveals that the phosphate is able to be involved in the interaction even though Ser(P)282 immediately precedes the PPXY motif. Coordination of Ser(P)282 with the end of only β-strand 3 enables Ser(P)279 to interact with the back face of β-strand 3 (Tyr286 is on the front face) and loop 2, forming the horseshoe-shaped arrangement. The observation that Ser(P)279 alone has no effect on the Cx43CT/Nedd4 WW2 domain binding affinity indicates that Ser(P)282 is necessary to coordinate the Ser(P)279 interaction. Of note, none of the WW2 residues within 5 Å of Ser(P)279 and Ser(P)282 are positively charged; thus the salt bridges formed by the phosphate of Smad3 Thr(P)179 with the Nedd4L or Pin1 WW domains would explain the approximately 2 orders of magnitude higher binding affinity than the Cx43CT/Nedd4 WW domain interaction.

Conclusion

This study presents the first structure illustrating how phosphorylation of the Cx43CT domain helps to mediate the interaction with a molecular partner. The similarity in structure between the three Nedd4 WW domains highlights how small changes in the primary sequence can alter the dynamics and binding interface to impact the binding affinity with the Cx43CT. Moreover, previous work from our laboratory suggested that different mechanisms of regulation exist between connexin isoforms even when involving the same molecular partners (67, 68). When examining the amino acid sequence of the CT of Cx40 (TPPPDF) and Cx45 (TPSAPPGY), two other cardiac connexins that co-express and co-oligomerize with Cx43, a similar PPXΦ motif can be observed. However, the position of the surrounding potential Ser(P)/Thr(P) residues is not directly adjacent to the PPXY motif, suggesting a distinct mechanism of interaction with and potential mode of regulation by Nedd4. Additionally, future studies need to address the Nedd4 (as well as other multidomain molecular partners) interaction with Cx43 in the context of a connexon. Can Nedd4 bind multiple Cx43CT domains? Can Nedd4 interact with the Cx43CT and a second protein partner at the same time? Does binding of Cx43 to each of the different WW domains of Nedd4 lead to a different response in the cell? Or is it just that increasing binding to any of them facilitates the same process (ubiquitination and endocytosis)?

Author Contributions

G. S. and F. K. conducted most of the experiments, analyzed the results, and edited the manuscript. J. L. K., H. L., S. Z., K. L. S., and R. G. helped G. S. and F. K. conduct the experiments and edit the manuscript. P. L. S. conceived the idea for the project, analyzed the results, and wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ed Ezell for assistance with NMR, Calliste Reiling for assistance with the ITC, and Jeff Lovelace for computer expertise. We gratefully thank Dr. Daniela Rotin (Toronto, Canada) for the generous gift of the Nedd4 WW1, WW2, and WW3 domain expression plasmids. We are also thankful to Ranjith Muhandiram (Lewis Kay laboratory, Toronto, Canada) for help with NMR data collection.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants GM072631 and P30CA036727, American Heart Association Grant 0560050Z, and the Nebraska Research Initiative funding for the Nebraska Center for Structural Biology. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 2n8s, 2n8u, and 2n8t) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

- CT

- C terminus

- Cx

- connexin

- Cx43CT

- C-terminal domain of Cx43

- Nedd4

- neuronal precursor cell-expressed developmentally down-regulated 4

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single quantum coherence

- ITC

- isothermal titration calorimetry

- r.m.s.d.

- root mean square deviation.

References

- 1. Oshima A. (2014) Structure and closure of connexin gap junction channels. FEBS Lett. 588, 1230–1237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Solan J. L., and Lampe P. D. (2014) Specific Cx43 phosphorylation events regulate gap junction turnover in vivo. FEBS Lett. 588, 1423–1429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hervé J. C., Bourmeyster N., Sarrouilhe D., and Duffy H. S. (2007) Gap junctional complexes: from partners to functions. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 94, 29–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smith T. D., Mohankumar A., Minogue P. J., Beyer E. C., Berthoud V. M., and Koval M. (2012) Cytoplasmic amino acids within the membrane interface region influence connexin oligomerization. J. Membr. Biol. 245, 221–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Martins-Marques T., Catarino S., Marques C., Matafome P., Ribeiro-Rodrigues T., Baptista R., Pereira P., and Girão H. (2015) Heart ischemia results in connexin43 ubiquitination localized at the intercalated discs. Biochimie 112, 196–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nimlamool W., Andrews R. M., and Falk M. M. (2015) Connexin43 phosphorylation by PKC and MAPK signals VEGF-mediated gap junction internalization. Mol. Biol. Cell 26, 2755–2768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Smyth J. W., Zhang S. S., Sanchez J. M., Lamouille S., Vogan J. M., Hesketh G. G., Hong T., Tomaselli G. F., and Shaw R. M. (2014) A 14-3-3 mode-1 binding motif initiates gap junction internalization during acute cardiac ischemia. Traffic 15, 684–699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fallon R. F., and Goodenough D. A. (1981) Five-hour half-life of mouse liver gap-junction protein. J. Cell Biol. 90, 521–526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ghoshroy S., Goodenough D. A., and Sosinsky G. E. (1995) Preparation, characterization, and structure of half gap junctional layers split with urea and EGTA. J. Membr. Biol. 146, 15–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jordan K., Chodock R., Hand A. R., and Laird D. W. (2001) The origin of annular junctions: a mechanism of gap junction internalization. J. Cell Sci. 114, 763–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Falk M. M., Fong J. T., Kells R. M., O'Laughlin M. C., Kowal T. J., and Thévenin A. F. (2012) Degradation of endocytosed gap junctions by autophagosomal and endo-/lysosomal pathways: a perspective. J. Membr. Biol. 245, 465–476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Girão H., Catarino S., and Pereira P. (2009) Eps15 interacts with ubiquitinated Cx43 and mediates its internalization. Exp. Cell Res. 315, 3587–3597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gumpert A. M., Varco J. S., Baker S. M., Piehl M., and Falk M. M. (2008) Double-membrane gap junction internalization requires the clathrin-mediated endocytic machinery. FEBS Lett. 582, 2887–2892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Piehl M., Lehmann C., Gumpert A., Denizot J. P., Segretain D., and Falk M. M. (2007) Internalization of large double-membrane intercellular vesicles by a clathrin-dependent endocytic process. Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 337–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cochrane K., Su V., and Lau A. F. (2013) The connexin43-interacting protein, CIP85, mediates the internalization of connexin43 from the plasma membrane. Cell Commun. Adhes. 20, 53–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fong J. T., Kells R. M., Gumpert A. M., Marzillier J. Y., Davidson M. W., and Falk M. M. (2012) Internalized gap junctions are degraded by autophagy. Autophagy 8, 794–811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Martins-Marques T., Catarino S., Zuzarte M., Marques C., Matafome P., Pereira P., and Girão H. (2015) Ischaemia-induced autophagy leads to degradation of gap junction protein connexin43 in cardiomyocytes. Biochem. J. 467, 231–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Thévenin A. F., Kowal T. J., Fong J. T., Kells R. M., Fisher C. G., and Falk M. M. (2013) Proteins and mechanisms regulating gap-junction assembly, internalization, and degradation. Physiology 28, 93–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ruch R. J., Trosko J. E., and Madhukar B. V. (2001) Inhibition of connexin43 gap junctional intercellular communication by TPA requires ERK activation. J. Cell. Biochem. 83, 163–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Leithe E., and Rivedal E. (2004) Ubiquitination and down-regulation of gap junction protein connexin-43 in response to 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate treatment. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 50089–50096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Leithe E., and Rivedal E. (2004) Epidermal growth factor regulates ubiquitination, internalization and proteasome-dependent degradation of connexin43. J. Cell Sci. 117, 1211–1220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kerscher O., Felberbaum R., and Hochstrasser M. (2006) Modification of proteins by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 22, 159–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Laing J. G., and Beyer E. C. (1995) The gap junction protein connexin43 is degraded via the ubiquitin proteasome pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 26399–26403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kjenseth A., Fykerud T., Rivedal E., and Leithe E. (2010) Regulation of gap junction intercellular communication by the ubiquitin system. Cell. Signal. 22, 1267–1273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Leithe E., Kjenseth A., Sirnes S., Stenmark H., Brech A., and Rivedal E. (2009) Ubiquitylation of the gap junction protein connexin-43 signals its trafficking from early endosomes to lysosomes in a process mediated by Hrs and Tsg101. J. Cell Sci. 122, 3883–3893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wagner S. A., Beli P., Weinert B. T., Nielsen M. L., Cox J., Mann M., and Choudhary C. (2011) A proteome-wide, quantitative survey of in vivo ubiquitylation sites reveals widespread regulatory roles. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 10, M111.013284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Leykauf K., Salek M., Bomke J., Frech M., Lehmann W. D., Dürst M., and Alonso A. (2006) Ubiquitin protein ligase Nedd4 binds to connexin43 by a phosphorylation-modulated process. J. Cell Sci. 119, 3634–3642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kumar S., Tomooka Y., and Noda M. (1992) Identification of a set of genes with developmentally down-regulated expression in the mouse brain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 185, 1155–1161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ingham R. J., Gish G., and Pawson T. (2004) The Nedd4 family of E3 ubiquitin ligases: functional diversity within a common modular architecture. Oncogene 23, 1972–1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Salah Z., Alian A., and Aqeilan R. I. (2012) WW domain-containing proteins: retrospectives and the future. Front. Biosci. 17, 331–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Catarino S., Ramalho J. S., Marques C., Pereira P., and Girão H. (2011) Ubiquitin-mediated internalization of connexin43 is independent of the canonical endocytic tyrosine-sorting signal. Biochem. J. 437, 255–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kieken F., Spagnol G., Su V., Lau A. F., and Sorgen P. L. (2010) NMR structure note: UBA domain of CIP75. J. Biomol. NMR 46, 245–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Duffy H. S., Sorgen P. L., Girvin M. E., O'Donnell P., Coombs W., Taffet S. M., Delmar M., and Spray D. C. (2002) pH-dependent intramolecular binding and structure involving Cx43 cytoplasmic domains. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 36706–36714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hirst-Jensen B. J., Sahoo P., Kieken F., Delmar M., and Sorgen P. L. (2007) Characterization of the pH-dependent interaction between the gap junction protein connexin43 carboxyl terminus and cytoplasmic loop domains. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 5801–5813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G. W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., and Bax A. (1995) NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 6, 277–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Johnson B. A., and Blevins R. A. (1994) NMR View: a computer program for the visualization and analysis of NMR data. J. Biomol. NMR 4, 603–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Brünger A. T., Adams P. D., Clore G. M., DeLano W. L., Gros P., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Jiang J. S., Kuszewski J., Nilges M., Pannu N. S., Read R. J., Rice L. M., Simonson T., and Warren G. L. (1998) Crystallography & NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54, 905–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Linge J. P., O'Donoghue S. I., and Nilges M. (2001) Automated assignment of ambiguous nuclear Overhauser effects with ARIA. Methods Enzymol. 339, 71–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nilges M., Macias M. J., O'Donoghue S. I., and Oschkinat H. (1997) Automated NOESY interpretation with ambiguous distance restraints: the refined NMR solution structure of the pleckstrin homology domain from β-spectrin. J. Mol. Biol. 269, 408–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Laskowski R. A., Rullmannn J. A., MacArthur M. W., Kaptein R., and Thornton J. M. (1996) AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J. Biomol. NMR 8, 477–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Koradi R., Billeter M., and Wüthrich K. (1996) MOLMOL: a program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 51–55, 29–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Whitmore L., and Wallace B. A. (2008) Protein secondary structure analyses from circular dichroism spectroscopy: methods and reference databases. Biopolymers 89, 392–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Whitmore L., and Wallace B. A. (2004) DICHROWEB, an online server for protein secondary structure analyses from circular dichroism spectroscopic data. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, W668–W673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Auer H. E. (1973) Far-ultraviolet absorption and circular dichroism spectra of L-tryptophan and some derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 95, 3003–3011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jäger M., Dendle M., and Kelly J. W. (2009) Sequence determinants of thermodynamic stability in a WW domain—an all-β-sheet protein. Protein Sci. 18, 1806–1813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kanelis V., Rotin D., and Forman-Kay J. D. (2001) Solution structure of a Nedd4 WW domain-ENaC peptide complex. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 407–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhang Y., and Skolnick J. (2004) Scoring function for automated assessment of protein structure template quality. Proteins 57, 702–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kelly S. M., and Price N. C. (2000) The use of circular dichroism in the investigation of protein structure and function. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 1, 349–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Berjanskii M. V., and Wishart D. S. (2005) A simple method to predict protein flexibility using secondary chemical shifts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 14970–14971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fischer M. W., Zeng L., Majumdar A., and Zuiderweg E. R. (1998) Characterizing semilocal motions in proteins by NMR relaxation studies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 8016–8019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bouvier D., Spagnol G., Chenavas S., Kieken F., Vitrac H., Brownell S., Kellezi A., Forge V., and Sorgen P. L. (2009) Characterization of the structure and intermolecular interactions between the connexin40 and connexin43 carboxyl-terminal and cytoplasmic loop domains. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 34257–34271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Johnstone S. R., Kroncke B. M., Straub A. C., Best A. K., Dunn C. A., Mitchell L. A., Peskova Y., Nakamoto R. K., Koval M., Lo C. W., Lampe P. D., Columbus L., and Isakson B. E. (2012) MAPK phosphorylation of connexin 43 promotes binding of cyclin E and smooth muscle cell proliferation. Circ. Res. 111, 201–211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Aragón E., Goerner N., Zaromytidou A. I., Xi Q., Escobedo A., Massagué J., and Macias M. J. (2011) A Smad action turnover switch operated by WW domain readers of a phosphoserine code. Genes Dev. 25, 1275–1288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zarrinpar A., and Lim W. A. (2000) Converging on proline: the mechanism of WW domain peptide recognition. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7, 611–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Warn-Cramer B. J., Cottrell G. T., Burt J. M., and Lau A. F. (1998) Regulation of connexin-43 gap junctional intercellular communication by mitogen-activated protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 9188–9196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Warn-Cramer B. J., Lampe P. D., Kurata W. E., Kanemitsu M. Y., Loo L. W., Eckhart W., and Lau A. F. (1996) Characterization of the mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylation sites on the connexin-43 gap junction protein. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 3779–3786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Morton T. A., and Myszka D. G. (1998) Kinetic analysis of macromolecular interactions using surface plasmon resonance biosensors. Methods Enzymol. 295, 268–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Myszka D. G., Morton T. A., Doyle M. L., and Chaiken I. M. (1997) Kinetic analysis of a protein antigen-antibody interaction limited by mass transport on an optical biosensor. Biophys. Chem. 64, 127–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lampe P. D., and Lau A. F. (2000) Regulation of gap junctions by phosphorylation of connexins. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 384, 205–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Toyofuku T., Akamatsu Y., Zhang H., Kuzuya T., Tada M., and Hori M. (2001) c-Src regulates the interaction between connexin-43 and ZO-1 in cardiac myocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 1780–1788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Duffy H. S., Ashton A. W., O'Donnell P., Coombs W., Taffet S. M., Delmar M., and Spray D. C. (2004) Regulation of connexin43 protein complexes by intracellular acidification. Circ. Res. 94, 215–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Morley G. E., Taffet S. M., and Delmar M. (1996) Intramolecular interactions mediate pH regulation of connexin43 channels. Biophys. J. 70, 1294–1302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Moreno A. P., Chanson M., Elenes S., Anumonwo J., Scerri I., Gu H., Taffet S. M., and Delmar M. (2002) Role of the carboxyl terminal of connexin43 in transjunctional fast voltage gating. Circ. Res. 90, 450–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Grosely R., Kopanic J. L., Nabors S., Kieken F., Spagnol G., Al-Mugotir M., Zach S., and Sorgen P. L. (2013) Effects of phosphorylation on the structure and backbone dynamics of the intrinsically disordered connexin43 C-terminal domain. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 24857–24870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Solan J. L., and Lampe P. D. (2007) Key connexin 43 phosphorylation events regulate the gap junction life cycle. J. Membr. Biol. 217, 35–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Shi H., Asher C., Chigaev A., Yung Y., Reuveny E., Seger R., and Garty H. (2002) Interactions of β and γ ENaC with Nedd4 can be facilitated by an ERK-mediated phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 13539–13547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Bouvier D., Kieken F., Kellezi A., and Sorgen P. L. (2008) Structural changes in the carboxyl terminus of the gap junction protein connexin 40 caused by the interaction with c-Src and zonula occludens-1. Cell Commun. Adhes. 15, 107–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kopanic J. L., Schlingmann B., Koval M., Lau A. F., Sorgen P. L., and Su V. F. (2015) Degradation of gap junction connexins is regulated by the interaction with Cx43-interacting protein of 75 kDa (CIP75). Biochem. J. 466, 571–585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]