Synopsis

The National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) was a large, multicenter, randomized, controlled trial published in 2011. It found that annual screening with low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) in a high-risk population was associated with a 20% reduction in lung cancer–specific mortality, compared with conventional chest radiography. Several leading professional organizations have since put forth lung cancer screening guidelines that include the use of LDCT, largely on the basis of this study. Broad adoption of these screening recommendations, however, remains a challenge.

Keywords: lung cancer, screening, low-dose computed tomography, NLST

INTRODUCTION

Screening for cancers in selected patient populations has become a well-established element of health care in the United States.1 The most common cancers, in order of decreasing incidence, are prostate, breast, lung, and colorectal.2 The treatment of breast and colorectal cancer have benefited from the widespread adoption of screening recommendations, whereas the treatment of prostate cancer, which the U.S. Preventative Service Task Force (USPSTF) does not have screening recommendations for (Table 1), has utilized the prostate specific antigen test and digital rectal examination for screening for many years.3 As a result, 93% of prostate cancers are diagnosed at a local or regional stage, and 61% of breast cancers are diagnosed at a local stage. These screening practices contribute to the high overall 5-year survival rates for prostate and breast cancer: 99.7% and 90.3%, respectively.4 The incidence of colorectal cancer has been decreasing by 2% to 3% per year during the past 15 years, while the rate of screening for colorectal cancer among average-risk patients has simultaneously grown to more than 60%.5

Table 1.

U.S. Preventative Service Task Force (USPSTF) Screening Recommendations

| Cancer | Specified Population | Screening Recommendation | Grade |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prostate | NA | No screening recommended | D |

| Breast | Women aged ≥ 40 years | Mammography every 1–2 years, with or without BSE | B |

| Colon | Adults aged 50–75 years | FOBT annually OR flexible sigmoidoscopy with FOBT every 3 years OR colonoscopy every 10 years | A |

| Cervical | Women aged 21–65 years | Pap smear every 3 years | A |

| Women aged 30–65 years wanting to lengthen screening interval | Pap smear and HPV testing every 5 years |

BSE, breast self-exam; FOBT, fecal occult blood testing; HPV, human papilloma virus; NA, not applicable.

Grade A: The USPSTF recommends the service. There is high certainty that the net benefit is substantial.

Grade B: The USPSTF recommends the service. There is high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial.

Grade D: The USPSTF recommends against the service. There is moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits.

Data from Recommendations. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. 2014; http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Name/recommendations. Accessed November 19, 2014.

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer death for both men and women in the United States, and it is expected to kill approximately 86,930 men and 72,330 women in 2014 in the United States alone.2 Yet, there is no broadly adopted screening protocol for patients at high risk of developing lung cancer. More than 400,000 people in the United States have a history of lung cancer, and an estimated 224,210 new cases will be diagnosed in 2014.4 Early stage lung cancers often develop asymptomatically or with nonspecific symptoms. This feature, combined with the lack of an established screening protocol, plays a role in 57% of non–small cell lung cancers being diagnosed at an advanced stage,4 which carries a dismal 5-year survival rate of only 4%.2 Alternatively, lung cancers diagnosed at an early stage have a much better 5-year survival rate, of 53.5%, with 68% of early stage lung cancers being amenable to surgical resection.4 Comparatively, only 8% of stage III and IV tumors were operatively managed in 2011.4 Thus, there is great potential to reduce mortality by establishing an early detection program for lung cancer.

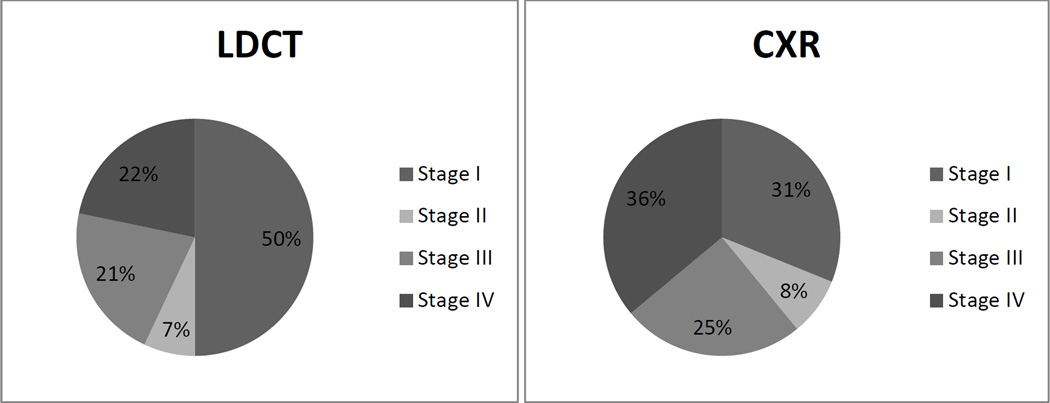

Several previous initiatives to assess the feasibility of early detection in individuals with the highest risk of developing lung cancer have been completed. Early trials investigating the utility of chest radiography (CXR) and sputum cytology as screening modalities were unable to demonstrate a mortality benefit.6–9 As imaging technologies have advanced, attention has turned to computed tomography (CT) as a modality for lung cancer screening.10–13 The Early Lung Cancer Action Project, for instance, published a series of 1000 patients that underwent low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) screening and suggested that this modality was superior to chest radiography (CXR) for detecting malignant nodules at early stages (Figure 1). While these initial findings were promising, this study was not designed to include a control arm for comparison necessitating further research.10 In 2011, the National Lung Screening Trial Research Group published results from the largest-to-date, randomized, multicenter study, which included more than 50,000 patients and tested the utility of low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) versus conventional CXR for lung cancer screening in high-risk patients. This well-developed and rigorous study observed a 20% decrease in disease-specific mortality in the LDCT group.14,15 Stated differently, 3 deaths were averted for every 1000 study participants screened annually during a 3-year period.16 The NLST was a landmark step forward toward the goal of early detection of lung cancer in high-risk patients.

Figure 1.

Diagnoses, by Stage, for LDCT and CXR

CXR, chest radiography; LDCT, low-dose computed tomography.

Data from Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395–409.

NATIONAL LUNG SCREENING TRIAL

Trial Design and Methods

The NLST was a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial funded by the National Cancer Institute that compared LDCT and CXR as screening modalities in patients considered to be at high-risk of developing lung cancer. The study enrolled 53,454 participants. The primary outcome was lung cancer mortality, which was compared between the two arms of the trial. Secondary outcomes included incidence of lung cancer and causes of death other than lung cancer. Participants were enrolled between August 2002 and April 2004 at 33 centers across the Unites States, and data were captured through December 31, 2009. Inclusion criteria were age between 55 and 74 years and a minimum smoking history of 30 pack-years (former smokers who quit smoking within 15 years of study enrollment were also included). Patients who reported a previous diagnosis of lung cancer, weight loss, or hemoptysis or who had undergone chest CT during the 18 months before enrollment were excluded. A total of 26,722 individuals were randomized to receive LDCT, and 26,732 were randomized to receive CXR. Participants in the LDCT group received a baseline CT scan, denoted as T0, and two subsequent annual LDCT scans, denoted as T1 and T2, respectively. The average effective dose of each LDCT scan was 1.5 mSv, which is less than 25% of the average effective radiation dose of a diagnostic chest CT scan.17 Subjects in the CXR group received a single-view posteroanterior CXR at baseline, followed by two annual screening CXRs.15 To ensure standardization of imaging and interpretation, radiologists and technologists who participated in the study were trained in accordance with NLST protocols. Positive CT findings included noncalcified nodules at least 4 mm in size, pleural effusions, and lymphadenopathy. Similarly, any noncalcified nodule or mass on CXR was considered a positive finding. Follow-up of positive findings was left to the discretion of the interpreting team, although guidelines were developed and made available. Stable nodules were defined as nodules that remained unchanged through all three rounds of LDCT screening.14

Results

Compliance remained high throughout the trial, with more than 90% of patients in each group completing the screening protocol. In total, 24% of patients in the LDCT group had positive screening results, compared with 7% in the CXR group. Positive scans, by screening interval, are shown in Table 2.14 As expected, there were fewer positive scans at the T2 interval, as some nodules followed through the course of the study were deemed to be stable. Overall, 39.1% of patients in the LDCT group and 16.0% of patients in the CXR group had at least 1 positive screen during the trial. Abnormalities that were not suspicious for lung cancer were found in 7.5% of subjects in the LDCT group and 2% of subjects in the CXR group.14

Table 2.

Positive Screens per Screening Interval

| LDCT | CXR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interval | Positive, no. (%) | Negative1 | Positive, no. (%) | Negative |

| T0 | 7191 (27.3) | 19,118 | 2387 (9.2) | 23,648 |

| T1 | 6901 (27.9) | 17,814 | 1482 (6.2) | 22,607 |

| T2 | 4054 (16.8) | 20,048 | 1174 (5.0) | 22,172 |

Negative, clinically significant abnormality not suspicious for lung cancer, minor abnormality, normal

CXR, chest radiography; LDCT, low-dose computed tomography.

Data from Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. The New England journal of medicine. Aug 4 2011;365(5):395–409.

Among the patients with a positive screening result, 1060 lung cancers were diagnosed in the LDCT group, compared with 941 in the CXR group. There were 356 deaths in the LDCT group and 443 in the CXR group. These findings represent a 20% decrease in disease-specific mortality in the LDCT group. All-cause mortality was 6.7% lower in the LDCT group than in the CXR group. False-positive rates were 96.4% in the LDCT group and 95.4% in the CXR group.14 The sensitivity and specificity of each intervention, by screening interval, are shown in Table 3. LDCT had a higher sensitivity for identifying lesions, compared with CXR, but LDCT had a lower specificity.18,19

Table 3.

Sensitivity and Specificity per Screening Interval

| LDCT | CXR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interval | Sensitivity | Specificity | Sensitivity | Specificity |

| T0 | 93.8 | 73.4 | 73.5 | 91.3 |

| T1 | 94.4 | 72.6 | 59.6 | 94.1 |

| T2 | 93.0 | 83.9 | 63.9 | 95.3 |

Data are percentages. CXR, chest radiography; LDCT, low-dose computed tomography.

Data from Aberle DR, DeMello S, Berg CD, et al. Results of the two incidence screenings in the National Lung Screening Trial. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(10):920–931 and Church TR, Black WC, Aberle DR, et al. Results of initial low-dose computed tomographic screening for lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(21):1980–1991.

The study found that approximately 90% of patients with a positive finding at the T0 interval underwent additional workup, which typically involved further imaging and less frequently involved invasive procedures, including percutaneous biopsy, bronchoscopy, or a surgical procedure. Complications occurred in 1.4% of patients in the LDCT group and 1.6% of patients in the CXR group. Most of the complications were in patients with a confirmed diagnosis of lung cancer.14 The reduction in lung cancer mortality observed in the LDCT group likely resulted from the increased diagnosis of early stage lung cancers. Fifty-seven percent of cancers diagnosed in the LDCT group were stage I or II tumors; in the CXR group, only 39% of cancers were diagnosed at similarly early stages. At the T1 screening interval, the CXR group had a higher percentage (59.1%) of disseminated cancers at diagnosis, compared with the LDCT group (31.1%).18 Overall, in the NLST study, there was a 2.7-fold increase in the diagnosis of lung cancer with LDCT screening, compared with CXR screening.18

COMPLICATIONS AND CONCERNS

Potential Harms of LDCT Screening

As listed in Box 1, there are several concerns associated with the broad implementation of LDCT for lung cancer screening. One of the most apparent potential harms is false-positive results, which occur with a high incidence. False-positives can increase anxiety in patients, prompting further diagnostic testing and carrying additional risks.17 Of the 17,053 patients in the NLST who received a positive screening result without subsequent confirmation of lung cancer, 457 (2.7%) underwent 1 or more invasive procedures (mediastinoscopy, thoracoscopy, thoracotomy, bronchoscopy, or needle biopsy), with 9.6% of these patients experiencing at least 1 complication.14 The incidence of invasive procedures among these patients can be contrasted with that among patients undergoing screening for breast cancer: 7% to 10% of biopsies among patients screened for breast cancer yielded nonmalignant diagnoses through 10 years of annual screening.20

Box 1. Concerns Associated with Low-Dose Computed Tomography Screening for Lung Cancer.

| False-positive results |

| Nonstandardized follow-up |

| Overdiagnosis |

| Radiation exposure |

| Cost |

| Nonadherence |

Overdiagnosis occurs when a cancer is diagnosed that would otherwise remain clinically insignificant.14 Such patients are then subjected to further diagnostic and therapeutic interventions, which carry risk. The extent of overdiagnosis in the NLST cannot be determined yet, as further follow-up is required.17 Screening guidelines for other tumors play a similar role in their overdiagnosis. An analysis of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program data found that, in 2008, 31% of breast cancers were overdiagnosed following screening mammography.21

With increasing exposure to ionizing radiation from screening or diagnostic CT scans, the risk of radiation-induced cancers must also be weighed.18 A diagnostic chest CT provides approximately 8 mSv of radiation, and a PET/CT delivers approximately 14 mSv.17 Although the level of radiation of a screening CT is much lower, at 1.5 mSv, this dose cannot be considered negligible in the context of repeated examinations. Annual screening for lung cancer by LDCT could result in a 0.2% to 0.85% increased lifetime risk of developing cancer, depending on age, sex, and smoking status.22 Overall, as many as 1.5% to 2% of cancers in the United States are estimated to be the result of radiation from current imaging use.23

Limitations of the NLST

Although the NLST was able to establish a significant associated decrease in lung cancer–specific mortality, the authors note several caveats to the global application of their findings. The study was performed at 33 medical centers with highly trained personnel and specialized physicians. Applicability at the community level is thus a concern, as image interpretation, follow-up, and management can vary. Patients subjected to screening within the community may likewise not reflect those recruited for the NLST. In what is recognized as the “healthy volunteer” effect, a bias toward findings with better outcomes may result from study participants. As the screenings for this study took place between 2002 and 2007, the authors note that newer-generation CT scanners in use now may lead to more “positive” scans. Last, the study showed a higher positive predictive value for lesions diagnosed at the T2 interval. Thus, continuing past three annual screenings may result in a greater reduction in mortality than the results of this study have demonstrated.14,18,19

In response to the large number of false-positive results and the low positive predictive value observed, the study authors also discussed refining the screening protocols. They note a low incidence of lung cancer in subjects between 55 and 59 years of age and suggest increasing the minimum age requirement for screening. As nodule size also correlated with likelihood of cancer, they suggest establishing predictive algorithms to better direct the follow-up for lesions found.18 The CT appearance of nodules in terms of percentage of solid component and histologic appearance can also be included in these models to increase the yield of true positives and reduce the false negative rate.24

DIFFICULTY IN APPROVAL BY THE CENTERS FOR MEDICARE AND MEDICAID SERVICES (CMS)

Despite the substantial associated survival benefit of LDCT demonstrated by the NLST, routine screening of high-risk patients with LDCT has not been widely adopted. In 2014, after reviewing the efficacy of LDCT, sputum cytology, and CXR in asymptomatic persons with average or high risk of developing lung cancer, the USPSTF updated their 2004 lung cancer screening recommendations to call for annual LDCT screening examinations in high-risk patients. The USPSTF recommendations are targeted at asymptomatic adults aged 55 to 80 years who have a smoking history of at least 30 pack-years and currently smoke or have quit within the previous 15 years. Screening examinations are to be discontinued for any one of the following three reasons: (1) if a person reaches 15 years of not smoking, (2) if a patient develops a severe health problem limiting life expectancy, or (3) if a patient is either unwilling or medically unable to undergo lung surgery with curative intent. The USPSTF has designated these recommendations grade B, which suggests to providers to offer this service, as it implies a high certainty that the net benefit is moderate. Table 4 lists the current screening guidelines of the leading professional organizations—all of them largely follow the NLST criteria.25

Table 4.

Recommendations for Lung Cancer Screening

| Organization | Specified population | Screening Recommendation |

Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States Preventative Services Task Force38 |

|

Annual LDCT | Grade B recommendation |

| American Cancer Society40 |

|

Annual LDCT at experienced screening center Recommends against CXR |

Discussion with patient before screening regarding harms and benefits |

| National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines41 |

|

Annual LDCT | Also recommend annual screening for those aged 50 and older with ≥ 20 pack-year smoking history, with additional comorbidity, with at least 5% risk of developing lung cancer during the next 5 years |

| American Association for Thoracic Surgery42 |

|

Annual LDCT | Also recommend annual screening for those aged 50 and older with ≥ 20 pack-year smoking history, with additional comorbidity, with at least 5% risk of developing lung cancer during the next 5 years |

| American College of Chest Physicians, American Society of Clinical Oncology, American Thoracic Society17 |

|

Annual LDCT | Screening settings should reflect NLST methods |

CXR, chest radiography; LDCT, low-dose computed tomography; NLST, National Lung Screening Trial.

Data from Humphrey L, Deffebach M, Pappas M, et al. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Evidence Syntheses, formerly Systematic Evidence Reviews. Screening for Lung Cancer: Systematic Review to Update the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2013.

Several studies have examined the NLST data from perspectives relevant for implementation. Stratification of the NLST patients into quintiles, as Bach and Gould have performed,16 produces two intriguing perspectives. First, the number of participants needed to be screened to prevent 1 lung cancer death—therefore, a measure of benefit to a patient—varies from 161 for the highest risk to 5276 for the lowest risk, a 33-fold difference. Second, a measure of benefit-harm tradeoff in the form of false-positive results per prevented lung cancer death also varied dramatically (25-fold), from 1648 to 65 false-positive results per prevented death. Furthermore, de Koning and colleagues26 have compiled modeling evidence based on NLST and Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial data and suggest that approximately 50% of lung cancers can be detected at early stages if certain high-risk patients are screened annually. On the basis of their analysis, this would result in a 14% reduction in lung cancer mortality, translating to an estimated 521 lung cancer deaths prevented per 100,000 persons in the population. Additional subgroup analysis of NLST data also suggests that statistically significant reductions in mortality could be achieved for patients with adenocarcinoma (relative risk, 0.75 [95% confidence interval, 0.60 to 0.94]) but not for patients with other lung cancer histologic profiles.27 Borderline statistically significant differences were also shown between men and women (relative risk, 0.73 for women vs. 0.92 for men; P = 0.08). In addition to the detection of 50% of cancers at early stages, 575 screening examinations per lung cancer death can be averted, with 5250 life-years gained per 100,000-member cohort. Interestingly, these modeling data are what prompted the USPSTF to broaden their target population, beyond the population set out in the NLST, to an upper age limit of 80 years and to recommend a maximum length of screening of 26 years, as opposed to the 3 years of screening in the NLST protocol.28 Such a screening program would not be without its harms, however, which are predicted to include 67,550 false-positive test results, 910 biopsies or surgeries for benign lesions, and 190 overdiagnosed cases of cancer. These potential harms, perhaps not surprisingly, play a central role in impeding the progress of broad implementation.29

A 2008 law titled “Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act” allows for the CMS to add new preventative services with USPSTF grade A or B recommendations, although it does not make doing so a requirement. Under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, USPSTF grade A or B recommendations earn waivers for deductibles and copayments in private insurance and Medicare. These new A or B recommendations may also be applied to private health plans on an annual basis, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.29 Critically, for lung cancer screening, Medicare is not subject to the same mandate.28 In April 2014, during the process of applying for CMS approval of LDCT screening, the Medicare Evidence Development and Coverage Advisory Committee delivered a vote of low confidence that the benefits of LDCT would outweigh the harms among Medicare beneficiaries in a community setting. This ruling surprised many, given the promising results of the well-designed NLST and the grade B recommendation from the USPSTF.

Relevant to the decision of the CMS, however, is further analysis of the data that reveals more nuance in the context of the Medicare patient population. Only 25% of patients studied in the NLST were older than 65, fewer than 10% were 70 years or older, and none were over the age of 74.28 Moreover, the potential harms associated with screening and its resulting workups are magnified in this population: older patients have higher complication rates from biopsy of pulmonary nodules,30 have higher postoperative mortality when their disease is resected,31 and are generally more susceptible to the harms of overtesting and overtreatment.17 Other important considerations for CMS include diminishing returns of screening among an aging population and, perhaps most importantly, the costs associated with screening.

In the wake of the publication of the NLST in 2012, Goulart and colleagues performed an economic analysis of the results.32 They found that LDCT screening will add $1.3 billion (in 2011 U.S. dollars) in annual national health care expenditures, for an uptake rate of 50%, progressing to $2.0 billion, for an uptake rate of 75%. At a 75% screening rate, LDCT screening is expected to prevent 8100 premature lung cancer deaths, with the cost of screening to avoid 1 lung cancer death $240,000. Further economic analysis, this time in the form of an actuarial review, conducted by Pyenson and colleagues (also in 2012),33 framed the discussion with relation to insurance coverage and reimbursement of LDCT screening. They found that the cost of lung cancer screening depends on various factors, ranging from the number of people screened to the prices charged, the types of screening, and the screening quality. The authors estimated the average annual cost of lung cancer screening to be $247 per person screened, assuming that 75% of the screenings are repeat procedures, which they reported to be consistent with previous large-scale screening programs.11 They developed three LDCT scenarios for cost per life-year saved, ranging from $11,708 to $26,016 (in 2012 U.S. dollars) for lung cancer screening, compared with for $31,309 to $51,274 for breast cancer screening by mammography, $18,705 to $28,958 for colorectal cancer screening by colonoscopy, and $50,162 to $75,181 for cervical cancer screening by Pap smear. Importantly, their LDCT screening population was a high-risk population, in the United States, aged 50 to 64 years, with a smoking history of at least 30 pack-years—a population that does not match the NLST participants in terms of age or align with the USPSTF recommendations. Nonetheless, their findings showed that screening would cost approximately $1 per insured member per month. The authors also qualify their findings by instructing payers and patients to seek screening from high-quality, low-cost providers, which again poses necessary questions for any potential systems-based screening mechanism. Building on this study, Villanti et al.34 added in the variables of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) to an analysis investigating the effects of smoking cessation, also using the same study population of a hypothetical cohort of 18 million adults between the ages of 50 and 64 with a smoking history of at least 30 pack-years. They reported a cost of $27.8 billion over 15 years, yielding 985,284 QALYs gained, for a cost-utility ratio of $28,240 per QALY gained (all in 2012 U.S. dollars). Furthermore, they found that adding smoking cessation increased both the costs and the QALYs saved, with a range of cost-utility ratios, from $16,198 per QALY gained to $23,185 per QALY gained. According to the authors, these estimates show screening to be highly cost-effective in their hypothetical high-risk cohort, especially when they include smoking cessation, which improved the cost-effectiveness of lung cancer screening by 20% to 45%.

Just as cost is an important practical consideration, patient adherence must also be thoroughly considered for any implementation of a screening program. Adherence to LDCT screening in the NLST was an uncharacteristically high 95%. The lessons from colon cancer screening show that follow-up is difficult in patients at the highest risk of developing disease.35 Furthermore, studies have shown that smokers at a higher risk of developing lung cancer are less interested in being screened, even though they recognize their level of risk.36 These concerns are also relevant when discussing implementation on a population-based level.

Accordingly, the USPSTF advocates for organized screening programs that include smoking cessation counseling when applicable, standardized scanning and image interpretation, quality standardization, and registry participation and validation, to ensure that LDCT screening achieves results similar to those of the NLST.37,38 Despite the NLST data, the myriad follow-up studies and analyses, and the favorable USPSTF recommendation, the prospect of broadly implementing LDCT screening for lung cancer in the United States will remain in doubt unless it is approved by the CMS.

SUMMARY

Screening protocols have become integrated as a standard of care for several solid tumor malignancies, including colon, prostate, and breast cancer. Following the finding in the 2011 NLST of a 20% decrease in lung cancer–specific mortality when LDCT screening is performed in high-risk patients, screening recommendations have been brought forth by several leading organizations. However, because of concerns about the cost and potential complications associated with false positive screens, particularly in the elderly population, approval for LDCT lung cancer screening by CMS is lacking. As a result, the future of lung cancer screening remains elusive in the current political and social climate.

Key Points.

In 2011, the National Lung Screening Trial demonstrated a 20% reduction in disease-specific mortality using low-dose computed tomography screening of a high-risk population, compared with chest radiography.

The United States Preventative Services Task Force recommends screening high-risk individuals aged 55 to 80 years with annual low-dose computed tomography.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services have yet to approve low-dose computed tomography screening for lung cancer in high-risk patients.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest/disclosure statement:

All authors declare no conflicts of interest and have no disclosures to make.

References

- 1.Wender RC, Smith R, Harper D. Cancer screening. Primary care. 2002 Sep;29(3):697–725. doi: 10.1016/s0095-4543(02)00019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2014 Jan-Feb;64(1):9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moyer VA. Screening for Prostate Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2012;157(2):120–134. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-2-201207170-00459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeSantis CE, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2014. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2014 Jul;64(4):252–271. doi: 10.3322/caac.21235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinberg DS, Schoen RE. Screening for colorectal cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2014 May 6;160(9) doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-160-9-201405060-01005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oken MM, Hocking WG, Kvale PA, et al. Screening by chest radiograph and lung cancer mortality: the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) randomized trial. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2011 Nov 2;306(17):1865–1873. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berlin NI. Overview of the NCI Cooperative Early Lung Cancer Detection Program. Cancer. 2000 Dec 1;89(11 Suppl):2349–2351. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001201)89:11+<2349::aid-cncr6>3.3.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melamed MR, Flehinger BJ, Zaman MB, Heelan RT, Perchick WA, Martini N. Screening for early lung cancer. Results of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering study in New York. Chest. 1984 Jul;86(1):44–53. doi: 10.1378/chest.86.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fontana RS, Sanderson DR, Woolner LB, Taylor WF, Miller WE, Muhm JR. Lung cancer screening: the Mayo program. Journal of occupational medicine. : official publication of the Industrial Medical Association. 1986 Aug;28(8):746–750. doi: 10.1097/00043764-198608000-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henschke CI, McCauley DI, Yankelevitz DF, et al. Early Lung Cancer Action Project: overall design and findings from baseline screening. Lancet. 1999 Jul 10;354(9173):99–105. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)06093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henschke CI, Yankelevitz DF, Libby DM, Pasmantier MW, Smith JP, Miettinen OS. Survival of patients with stage I lung cancer detected on CT screening. The New England journal of medicine. 2006 Oct 26;355(17):1763–1771. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pastorino U, Bellomi M, Landoni C, et al. Early lung-cancer detection with spiral CT and positron emission tomography in heavy smokers: 2-year results. Lancet. 2003 Aug 23;362(9384):593–597. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14188-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swensen SJ, Jett JR, Hartman TE, et al. Lung cancer screening with CT: Mayo Clinic experience. Radiology. 2003 Mar;226(3):756–761. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2263020036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. The New England journal of medicine. 2011 Aug 4;365(5):395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aberle DR, Berg CD, Black WC, et al. The National Lung Screening Trial: overview and study design. Radiology. 2011 Jan;258(1):243–253. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10091808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bach PB, Gould MK. When the average applies to no one: personalized decision making about potential benefits of lung cancer screening. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Oct 16;157(8):571–573. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-8-201210160-00524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bach PB, Mirkin JN, Oliver TK, et al. Benefits and harms of CT screening for lung cancer: a systematic review. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2012 Jun 13;307(22):2418–2429. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aberle DR, DeMello S, Berg CD, et al. Results of the two incidence screenings in the National Lung Screening Trial. The New England journal of medicine. 2013 Sep 5;369(10):920–931. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1208962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Church TR, Black WC, Aberle DR, et al. Results of initial low-dose computed tomographic screening for lung cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2013 May 23;368(21):1980–1991. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pace LE, Keating NL. A systematic assessment of benefits and risks to guide breast cancer screening decisions. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2014 Apr 2;311(13):1327–1335. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bleyer A, Welch HG. Effect of three decades of screening mammography on breast-cancer incidence. The New England journal of medicine. 2012 Nov 22;367(21):1998–2005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1206809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brenner DJ. Radiation risks potentially associated with low-dose CT screening of adult smokers for lung cancer. Radiology. 2004 May;231(2):440–445. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2312030880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brenner DJ, Hall EJ. Computed tomography--an increasing source of radiation exposure. The New England journal of medicine. 2007 Nov 29;357(22):2277–2284. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brawley OW, Flenaugh EL. Low-dose spiral CT screening and evaluation of the solitary pulmonary nodule. Oncology (Williston Park, N.Y.) 2014 May;28(5):441–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Humphrey L, Deffebach M, Pappas M, et al. Screening for Lung Cancer: Systematic Review to Update the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2013. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Evidence Syntheses, formerly Systematic Evidence Reviews. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Koning HJ, Meza R, Plevritis SK, et al. Benefits and harms of computed tomography lung cancer screening strategies: a comparative modeling study for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Annals of internal medicine. 2014 Mar 4;160(5):311–320. doi: 10.7326/M13-2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pinsky PF, Church TR, Izmirlian G, Kramer BS. The National Lung Screening Trial: results stratified by demographics, smoking history, and lung cancer histology. Cancer. 2013 Nov 15;119(22):3976–3983. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bach PB. Raising the Bar for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2014;160(5):365–366. doi: 10.7326/M13-2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wiener RS. Balancing the Benefits and Harms of Low-Dose Computed Tomography Screening for Lung Cancer: Medicare's Options for Coverage. Ann Intern Med. 2014 Jun 24; doi: 10.7326/M14-1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wiener RS, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S, Welch HG. Population-based risk for complications after transthoracic needle lung biopsy of a pulmonary nodule: an analysis of discharge records. Ann Intern Med. 2011 Aug 2;155(3):137–144. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-155-3-201108020-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kozower BD, Sheng S, O'Brien SM, et al. STS database risk models: predictors of mortality and major morbidity for lung cancer resection. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2010 Sep;90(3):875–881. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.03.115. discussion 881-873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goulart BH, Bensink ME, Mummy DG, Ramsey SD. Lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography: costs, national expenditures, and cost-effectiveness. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. 2012 Feb;10(2):267–275. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pyenson BS, Sander MS, Jiang Y, Kahn H, Mulshine JL. An actuarial analysis shows that offering lung cancer screening as an insurance benefit would save lives at relatively low cost. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2012 Apr;31(4):770–779. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Villanti AC, Jiang Y, Abrams DB, Pyenson BS. A cost-utility analysis of lung cancer screening and the additional benefits of incorporating smoking cessation interventions. PloS one. 2013;8(8):e71379. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baig N, Myers RE, Turner BJ, et al. Physician-reported reasons for limited follow-up of patients with a positive fecal occult blood test screening result. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2003 Sep;98(9):2078–2081. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silvestri GA, Nietert PJ, Zoller J, Carter C, Bradford D. Attitudes towards screening for lung cancer among smokers and their non-smoking counterparts. Thorax. 2007 Feb;62(2):126–130. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.056036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Detterbeck FC, Unger M. Screening for lung cancer: moving into a new era. Ann Intern Med. 2014 Mar 4;160(5):363–364. doi: 10.7326/M13-2904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moyer VA. Screening for Lung Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2014;160(5):330–338. doi: 10.7326/M13-2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Recommendations. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. [Accessed July 30, 2014];2014 http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/recommendations.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wender R, Fontham ET, Barrera E, Jr, et al. American Cancer Society lung cancer screening guidelines. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2013 Mar-Apr;63(2):107–117. doi: 10.3322/caac.21172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.National Comprehensive Cancer Center. [Accessed July 30, 2014];NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines In Oncology: Lung Cancer Screening. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/lung_screening.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jaklitsch MT, Jacobson FL, Austin JH, et al. The American Association for Thoracic Surgery guidelines for lung cancer screening using low-dose computed tomography scans for lung cancer survivors and other high-risk groups. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2012 Jul;144(1):33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.05.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]