Abstract

Deception is common in nature and humans are no exception1. Modern societies have created institutions to control cheating, but many situations remain where only intrinsic honesty keeps people from cheating and violating rules. Psychological2, sociological3 and economic theories4 suggest causal pathways about how the prevalence of rule violations in people's social environment such as corruption, tax evasion, or political fraud can compromise individual intrinsic honesty. Here, we present cross-societal experiments from 23 countries around the world, which demonstrate a robust link between the prevalence of rule violations and intrinsic honesty. We developed an index of the Prevalence of Rule Violations (PRV) based on country-level data of corruption, tax evasion, and fraudulent politics. We measured intrinsic honesty in an anonymous die-rolling experiment.5 We conducted the experiments at least eight years after the measurement of PRV with 2568 young participants (students) who could not influence PRV. We find individual intrinsic honesty is stronger in the subject pools of low PRV countries than those of high PRV countries. The details of lying patterns support psychological theories of honesty.6,7 The results are consistent with theories of the cultural co-evolution of institutions and values8 and show that weak institutions and cultural legacies9-11 that generate rule violations not only have direct adverse economic consequences but might also impair individual intrinsic honesty that is crucial for the smooth functioning of society.

Keywords: deception, institutions, cross-cultural experiments, psychology of honesty, behavioural ethics

Good institutions that limit cheating and rule violations, such as corruption, tax evasion and political fraud are crucial for prosperity and development.12,13 Yet, even very strong institutions cannot control all situations that may allow for cheating. Well functioning societies also require citizens' intrinsic honesty. Cultural characteristics, such as whether people see themselves as independent or part of a larger collective, that is, how individualist or collectivist9 a society is, might also influence the prevalence of rule violations due to differences in the perceived scope of moral responsibilities, which is larger in more individualist cultures.10,14 Here, we investigate how the prevalence of rule violations in a society and individual intrinsic honesty are linked. A variety of psychological, sociological and economic theories suggest causal pathways of how widespread practices of violating rules can affect individual honesty and the intrinsic willingness to follow rules.

Generally, processes of conformist transmission of values, beliefs, and experiences influence individuals strongly and thereby can produce differences between social groups.15 The extent to which people follow norms also depends on how prevalent norm violations are.3 If cheating is pervasive in society and goes often unpunished, then people might view dishonesty in certain everyday affairs as justifiable without jeopardising their self-concept of being honest.2 Experiencing frequent unfairness, an inevitable by-product of cheating, can also increase dishonesty16. Economic systems, institutions, and business cultures shape people's ethical values8,17,18 and can likewise impact individual honesty.19,20

Ethical values, including honesty, are transmitted from prestigious people, peers, and parents. People often take high-status individuals such as business leaders and celebrities as role models21 and their cheating can set bad examples for dishonest practices.19 Similarly, if politicians set bad examples by using fraudulent means like rigging elections, nepotism and embezzlement, then the citizens’ honesty might suffer, because corruption is fostered in wider parts of society.13 If many people work in the shadow economy and thereby evade taxes, peer effects might make cheating more acceptable.22 If corruption is endemic in society, parents may recommend a positive attitude towards corruption and other acts of dishonesty and rule violations as a way to succeed in this environment.4,23

To measure the extent of society-wide practices of rule violations we construct an index of the 'Prevalence of Rule Violations' (PRV). We focus on three broad types of rule violations: political fraud, tax evasion, and corruption. We construct PRV by calculating the principal component of three widely-used country-level variables that all rest on comprehensive, often representative data sources to capture the important dimensions of the prevalence of rule violations we are interested in: an indicator of political rights by Freedom House that measures the democratic quality of a country’s political practices; the size of a country's shadow economy as a proxy for tax evasion; and corruption as measured by the World Bank's Control of Corruption index (Supplementary Methods).

We construct PRV for the 159 countries for which data are available for all three variables, the earliest year being 2003. We use the 2003 data to maximise the distance between the measurement of PRV and the point in time the experiments were run (at least 8 years later), to ensure that our participants could not have influenced PRV. PRV in 2003 has a mean of 0 (s.d. 1.46), and it ranges from −3.1 to 2.8 (higher values indicate higher prevalence of rule violations).

Our strategy was to conduct comparable experiments in 23 diverse countries with a distribution of PRV that resembles the world distribution of PRV: In the countries of our sample, PRV in 2003 ranges from −3.1 to 2.0, with a mean of −0.7 (s.d. 1.52). Thus, the distribution of PRV in our sample is approximately representative of the world distribution of PRV with a slight bias towards lower PRV countries. The countries of our sample also vary strongly according to frequently used cultural indicators such as individualism and value orientations (Extended Data Table 1; Supplementary Methods).

Our participants, all nationals of the respective country, were young people with comparable socio-demographic characteristics (students; mean age: 21.7 (s.d. 3.3) years; 48% females; Supplementary Methods) who due to their youth had limited chances of being involved in political fraud, tax evasion, and corruption, but might have been exposed to (or socialised into) certain attitudes towards (dis-)respecting rules.24

Our experimental tool to measure intrinsic honesty was the ‘die-in-a-cup’ task5. Participants sat in a cubicle and were asked to roll a six-sided die placed in an opaque cup twice, but to report the first roll only. Die rolling was unobservable by anyone except the subject (Extended Data Fig. 1). Participants were paid according to the number they reported: reporting a 1 earned the participant 1 money unit (MU), claiming a 2 earned 2 MU, etc., except reporting a 6 earned nothing. Participants understood that reports were unverifiable. Across countries, MU reflected local purchasing power (Supplementary Methods). Thus, incentives in the experiment are the same for everyone, whether they live in a high or low PRV environment.

While individual dishonesty is not detectable, aggregate behaviour is informative. In an honest subject pool all numbers occur with probability 1/6 and the average claim is 2.5 MU. We refer to this as the Full Honesty benchmark. By contrast, in the Full Dishonesty benchmark, subjects follow their material incentives and claim 5 MU.

The die-in-a-cup task requires only a simple non-strategic decision, and it allows for gradual dishonesty predicted by psychological theories of honesty.6,7 An experimentally-tested theory of “justified ethicality”7 applied to our setting argues that many people have a desire to maintain an honest self-image. Reporting a counterfactual die roll jeopardises this self-image, but bending rules might not. Bending the rules is to report the higher of the two rolls, rather than the first roll as required. Reporting the better of two rolls implies the Justified Dishonesty benchmark: claims of 0 should occur in 1/36 ≈ 2.8% of the cases (after rolling 6-6); claims of 1 should occur in 3/36 ≈ 8.3% (after 6-1, or 1-6, or 1-1); claims of 2, 3, 4 and 5 should occur in 13.9%, 19.4%, 25%, and 30.6% of cases, respectively.

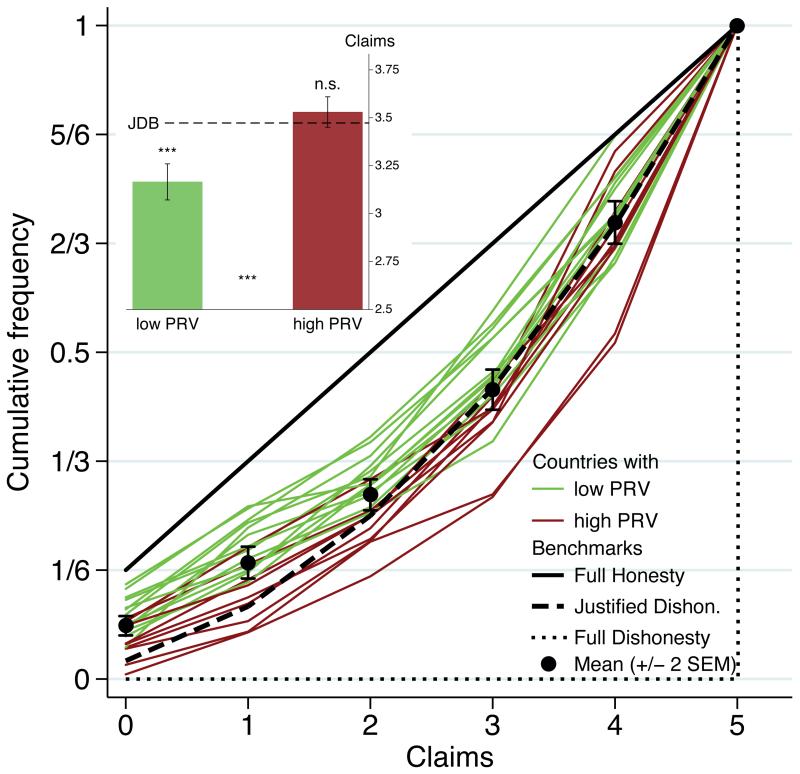

Fig. 1 illustrates the benchmarks, presented as cumulative distribution functions (CDFs). Fig. 1 also shows the empirical CDF for each subject pool. CDFs are far away from Full Dishonesty. CDFs are also bent away from Full Honesty and cluster around the Justified Dishonesty benchmark. One-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests for discrete data reject the null hypotheses of equality of CDFs with the Full Honesty benchmarks for every subject pool, but cannot reject the null hypothesis in 13 subject pools in comparisons with the Justified Dishonesty benchmark (Extended Data Fig. 2a).

Figure 1. Distributions of reported die rolls.

Depicted are the cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) of amounts claimed compared to the CDFs of the Full Honesty, Justified Dishonesty and Full Dishonesty benchmarks. Green coloured CDFs represent subject pools (nlow = 14) from countries with a below-average Prevalence of Rule Violations (PRV; mean PRVlow = −1.69), and red coloured CDFs represent subject pools (nhigh = 9) from countries with above-average PRV (mean PRVhigh = 0.78) out of 159 countries. Inset, the average claim is shown for subjects from below average (‘low’, nlow = 1211) and above average (‘high’, nhigh = 1211) PRV countries. *** P < 0.01, two-sided t-tests; n.s. P > 0.14. JDB is the Justified Dishonesty benchmark.

Deviations from the Justified Dishonesty benchmark are related to PRV. The CDFs of subject pools from low PRV countries tend to be above the CDF implied by Justified Dishonesty, and also above those of most high PRV countries. Comparing the distributions of claims pooled for all low and high PRV countries, respectively, reveals a highly significant difference (nlow = 1211, nhigh = 1357; χ2(5) = 40.21, P < 0.001). The pooled CDF from high PRV countries first-order stochastically dominates the pooled CDF from low PRV countries, that is, subjects from low PRV countries are more honest than subjects from high PRV countries. The pooled CDF from low PRV countries also lies significantly above Justified Dishonesty (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, d = 0.103, P < 0.001), whereas the pooled CDF from high PRV countries tends to be slightly below it (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, d = 0.058, P < 0.001; Extended Data Fig. 2b; Supplementary Analyses).

The inset figure illustrates the implications of these patterns in terms of average claims. Subjects from low PRV countries claim 3.17 MUs (s.d. 1.67), that is, 0.67 MU more than under Full Honesty. Subjects from high PRV countries claim 3.53 MU (s.d. 1.49) or 1.03 MU more than under Full Honesty. This difference in claims is significant (t-test, t = 5.84, two-sided P < 0.001); it also holds at the country level (n = 23; Mann-Whitney test, z = 3.40, two-sided P < 0.001). Justified Dishonesty implies an expected claim of 3.47 MU. The average claim in high PRV countries is not significantly different from this benchmark (one-sample t-test, nhigh = 1357, t = 1.48, two-sided P = 0.140), but is significantly lower in low PRV countries (one-sample t-test, nlow = 1211, t = 6.35, two-sided P < 0.001).

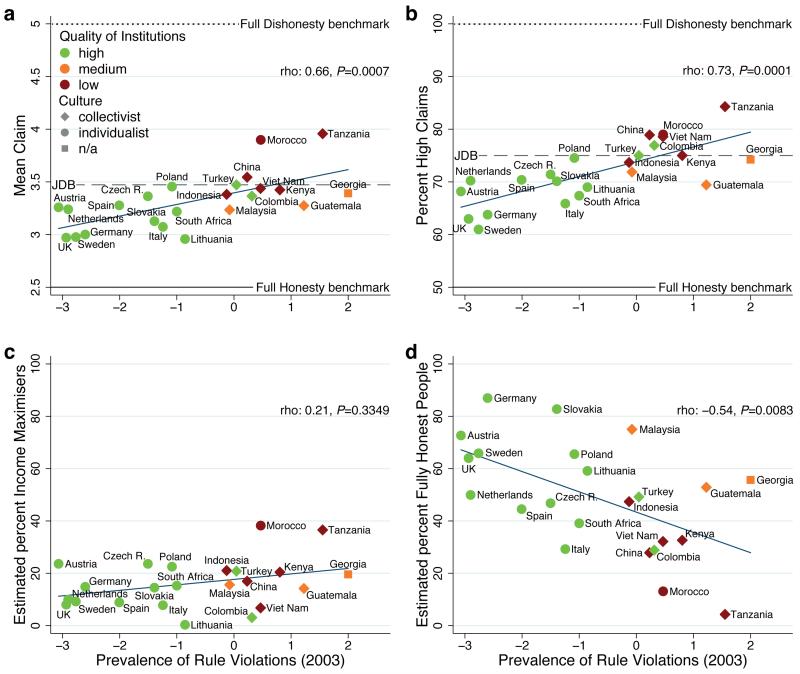

Next we look at four measures of dishonesty one can derive from our task (Supplementary Information) and relate them to country-level PRV (Fig. 2). A first measure of dishonesty is Mean Claim, which ranges from 2.96 MU to 3.96 MU across countries (mean 3.32 MU, s.d. 0.26; Kruskal-Wallis test, χ2(22) = 75.2, P < 0.001). PRV and Mean Claim are strongly positively related (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2. Measures of honesty and the prevalence of rule violations in society.

Shown are scatter plots of four measures of honesty and PRV at country level (n = 23); higher values indicate more rule violations. a, Mean Claim. b, Percent High Claims of 3, 4, and 5 MU. c, Percent Income Maximisers estimated from the fraction of people claiming 5 MU. d, Percent Fully Honest People estimated from the fraction of people claiming 0 MU. rho is the Spearman rank correlation based on country means. JDB is the Justified Dishonesty benchmark (not defined for c and d). Colour coding refers to the Quality of Institutions as measured by Constraints on Executives; shapes distinguish between countries classified as collectivist or individualist. PRV is negatively correlated with Constraints on Executives and Individualism (Supplementary Information); this also holds in our sample (Constraint on Executive: rho = −0.76, n = 23, P < 0.0001; Individualism: rho= −0.79, n = 22, P < 0.0001).

A second measure is the frequency of High Claims 3, 4 and 5, which should occur at 50% if people are honest and at 75% under Justified Dishonesty. Frequencies range from 61.0% to 84.3% (mean 71.8%, s.d. 5.7%; χ2(22) = 45.0, P = 0.003). PRV and High Claims are strongly positively associated (Fig. 2b).

Incentives are to claim 5, irrespective of the number actually rolled. Thus, the fraction of Income Maximisers provides our third measure of dishonesty. It is estimated from the fraction of people who reported 5 (Highest Claim) minus the expected rate of actual rolls of 5 (16.7%). To account for income maximisers who actually rolled a 5 the difference has to be multiplied by 6/5.5 The rate of income maximisers ranges from 0.3% to 38.3% across subject pools (mean 16.2%, s.d. 9.4%; χ2(22) = 72.4, P < 0.001). Given that PRV captures rule violations for selfish gains and evidence suggesting rule breakers tend to be more selfish25 we predict that Income Maximisers is positively correlated with PRV. We find, however, that they are unrelated (Fig. 2c). Thus, a society’s PRV does not systematically affect maximal cheating in this experiment.

This result is in stark contrast to the observation that the estimated fraction of Fully Honest People and PRV are significantly negatively related (Fig. 2d). The fraction of Fully Honest People, our fourth measure, is estimated from No Claim, that is, reports of 6. A report of 6 is most likely honest and honest reports can occur for all numbers. Therefore, the fraction of Fully Honest People can be estimated as the fraction of people reporting 6 multiplied by six. Across subject pools, Fully Honest People ranges from 4.3% to 87% (mean 48.9%, s.d. 21.3%; χ2(22) = 42.1, P = 0.006). In societies with high levels of PRV, fewer people are fully honest than in societies with low levels of PRV.

Regression analyses that control for individual attitudes to honesty and beliefs in the fairness of others, as well as for socio-demographics confirm the robustness of our results (Extended Data Table 2; Supplementary Analysis). Socio-demographic variables, including gender, are generally insignificant. Stronger individual norms of honesty significantly reduce Mean Claim, High Claim and Highest Claim. Beliefs in the fairness of others only significantly reduce Highest Claim.

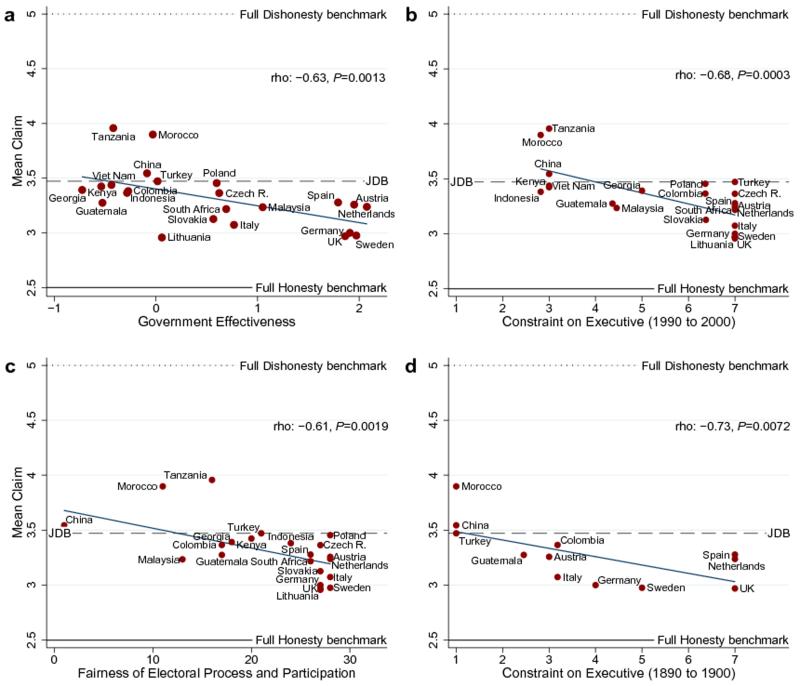

Results are also robust using the earliest available data related to PRV, corruption in 1996; using Government Effectiveness, a proxy for bureaucratic quality and material security11 and measures of institutional quality that emphasise law enforcement (rules) and not actual compliance and that also extend far into the past, so they are most likely not influenced even by parents (Extended Data Fig. 3a-d; Supplementary Analysis).

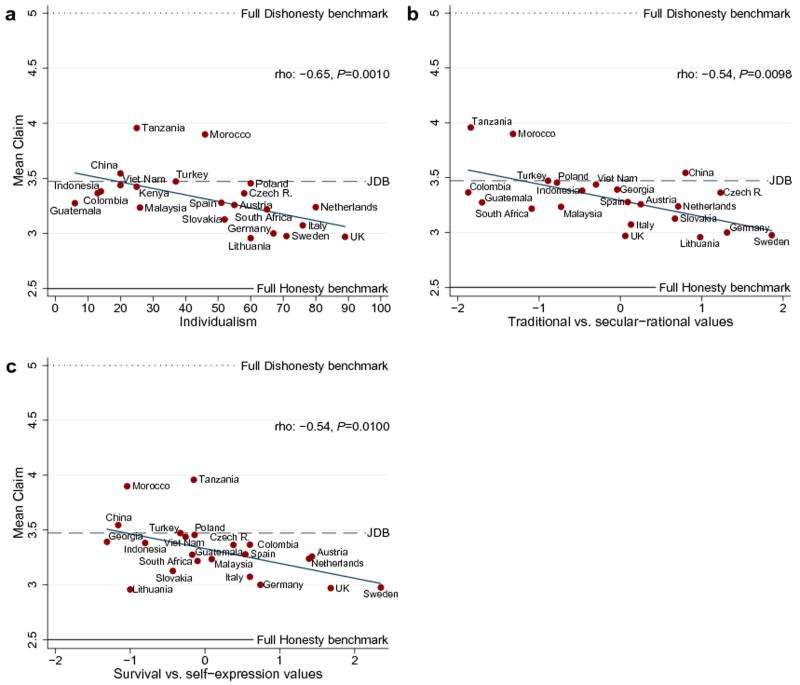

Given that the experiment holds the rules and incentives constant for everyone, the large differences across subject pools are also consistent with a cultural transmission of norms of honesty and rule following through the generations4,15,23 and a co-evolution of norms and institutions8. Societies with higher material security, as measured by Government Effectiveness, tend to be more individualist11 and more individualist societies tend to have less corruption10. Consistent with this, we find that subject pools from individualist societies have lower claims than subject pools from more collectivist societies and also from more traditional societies and societies with survival-related values (Extended Data Fig. 4a-c; Supplementary Analysis). Further econometric analyses developed in economic literature on culture and institutions14 applied to PRV support the argument that both the quality of institutions as well as culture (individualism) are highly significantly (and likely causally) correlated with PRV (Extended Data Table 3; Supplementary Analysis).

Taken together, our results suggest that institutions and cultural values influence PRV, which, through various theoretically predicted and experimentally tested pathways2,11,16,19,20,22-26, impact on people’s intrinsic honesty and rule following. Our experiments from around the globe provide also novel support for arguments that for many people lying is psychologically costly.27-30 More specifically, theories of honesty posit that many people are either honest, or (self-deceptively1) bend rules or lie gradually to an extent that is compatible with maintaining an honest self-image6,7. Evidence for lying aversion and honest self-concepts has been mostly confined to western societies with low PRV values.30 Our expanded scope of societies therefore provides important support and qualifications for the generalizability of these theories: people benchmark their justifiable dishonesty with the extent of dishonesty they see in their societal environment.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. The die-in-a-cup task (due to Fischbacher and Föllmi-Heusi5).

Participants (n = 2568 from 23 countries) are asked to roll the die twice in the cup and to report the first roll. Payment is according to reported roll, except reporting 6 earns 0 money units (MU; across subject pools MU in local currency are adjusted to equalise purchasing power). We used the same set of dice in all subject pools, and we also tested the dice for biasedness. The procedures followed established rules in cross-cultural experimental economics. See Supplementary Information for further details. This picture was taken by J.S. in the experimental laboratory of the University of Nottingham.

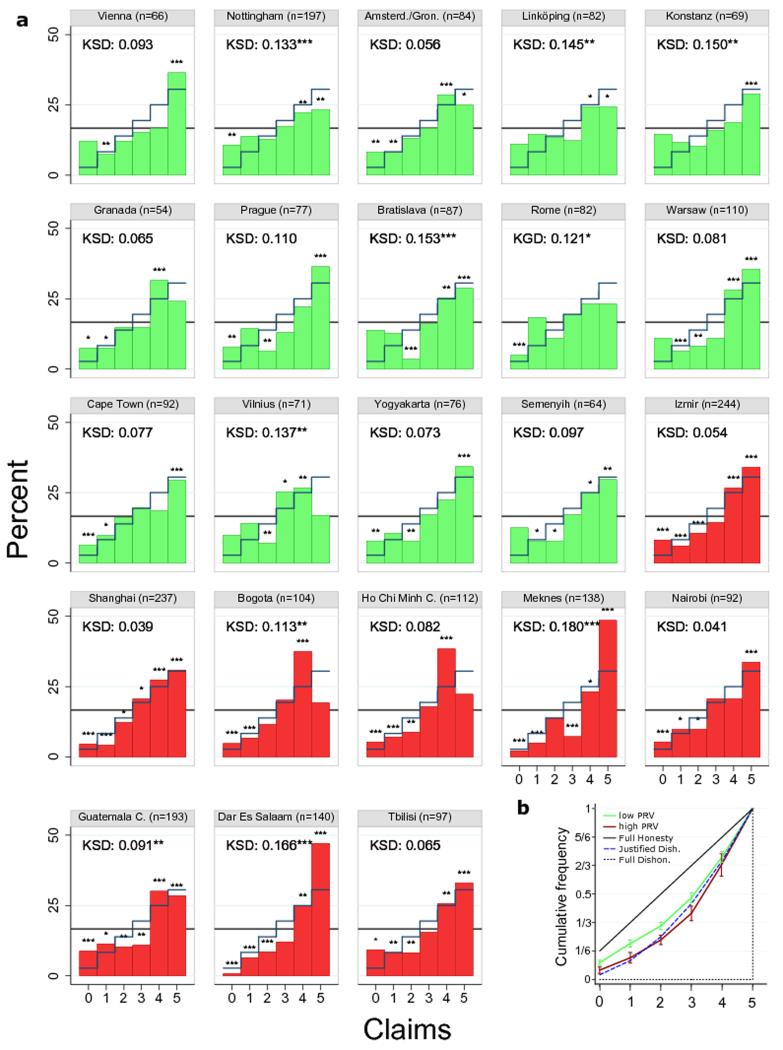

Extended Data Figure 2. Distribution of claims.

a. Distribution per subject pool. Subject pools are ordered by country PRV. The first 14 subject pools (in green) are from “low” (below-average) PRV countries; the last 9 subject pools (in red) are from “high” (above-average) PRV countries relative to the world sample of 159 countries. The horizontal black line refers to the uniform distribution implied by honest reporting and the blue step function to the distribution implied by the Justified Dishonesty benchmark (JDB). For each subject pool we report the one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (KS) for discrete data in comparison with JDB (KSD is the KS d value). Stars above bars refer to binomial tests comparing the frequency of a particular claim with its predicted value under a uniform distribution. b. Cumulative distributions for pooled data from subject pools from low and high PRV countries, respectively. See Supplementary Analysis for further information. * P < 0.1, ** P < 0.05, *** P < 0.01.

Extended Data Figure 3. Association between indicators of institutional quality and intrinsic honesty as measured by Mean Claim.

The blue line is a linear fit. The line marked ‘JDB’ indicates the ‘Justified Dishonesty benchmark’. rho indicates Spearman rank order correlation coefficients. Mean Claim is negatively related to a. Government Effectiveness; b. Constraint on Executive; c. ‘Fairness of Electoral Process and Participation’; d. Constraint on Executive using the averages of the years 1890 to 1900 as a measure for distant institutional quality. See Extended Data Table 1 and Supplementary Information for data description, references, and further analyses.

Extended Data Figure 4. Association between cultural indicators and intrinsic honesty as measured by Mean Claim.

The blue line is a linear fit. The line marked ‘JDB’ indicates the ‘Justified Dishonesty benchmark’. rho indicates Spearman rank order correlation coefficients. Mean Claim is negatively related to a. Individualism; b. Traditional vs. secular-rational values; c. Survival vs. self-expression values. See Extended Data Table 1 and Supplementary Information for data description, references, and further analyses.

Extended Data Table 1.

Measures of prevalence of rule violations, economic and institutional variables, as well as cultural background of our subject pools

Data are country-level averages. Detailed descriptions, data sources, and references are in the Supplementary Information. Control of Corruption is a standard measure of corruption; higher values indicate more corruption. Shadow Economy is measured in percent of the size of a country’s GDP. Political Rights measures the fairness of electoral processes, political pluralism and participation, and the functioning of government; higher scores indicate higher level of political rights. Prevalence of Rule Violations is our self-constructed indicator based on a principal component analysis of Control of Corruption, Shadow Economy, and Political Rights. Government Effectiveness measures the quality of public service, independence from political pressure and policy implementation; higher values indicate higher effectiveness. Constraint on Executive measures the institutionalised limitations on the arbitrary use of power by the executive; higher values indicate better control. GDP per capita (average of 1990 to 2000) is measured in US-$ 1’000 (PPP)). Individualism measures how important the individual is relative to the collective; higher values indicate higher individualism. Traditional vs. secular-rational values measures the importance of values such as respect for authorities; higher scores indicate more secular values. Survival vs self-expression values measure the importance of values surrounding physical and economic security; lower scores indicate survival values are relatively more important than self-expression values. World mean and sample mean are the respective averages of country means.

| Indicators of rule violations |

Institutional and economic indicators |

Cultural Indicators |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control of Corruption |

Shadow Economy | Political rights | Prevalence of Rule Violations |

Constraint on Executive |

Government Effectiveness |

GDP per capita | Individualism | Traditional vs secular-rational values |

Survival vs. self- expression values |

|

| Austria | 2.1 | 10 | 40 | −3.1 | 7.0 | 2.0 | 23.3 | 55 | 0.3 | 1.4 |

| China | −0.4 | 13 | 3 | 0.2 | 3.0 | −0.1 | 1.5 | 20 | 0.8 | −1.2 |

| Colombia | −0.2 | 38 | 23 | 0.3 | 6.4 | −0.3 | 5.3 | 13 | −1.9 | 0.6 |

| Czech R. | 0.4 | 19 | 37 | −1.5 | 7.0 | 0.6 | 14.1 | 58 | 1.2 | 0.4 |

| Georgia | −0.6 | 66 | 19 | 2.0 | 5.0 | −0.7 | 1.8 | n.a. | −0.0 | −1.3 |

| Germany | 1.9 | 16 | 38 | −2.6 | 7.0 | 1.9 | 22.1 | 67 | 1.3 | 0.7 |

| Guatemala | −0.7 | 51 | 22 | 1.2 | 4.4 | −0.5 | 3.4 | 6 | −1.7 | −0.2 |

| Indonesia | −1.0 | 19 | 26 | −0.1 | 2.8 | −0.3 | 2.1 | 14 | −0.5 | −0.8 |

| Italy | 0.5 | 27 | 38 | −1.2 | 7.0 | 0.8 | 20.7 | 76 | 0.1 | 0.6 |

| Kenya | −0.8 | 35 | 18 | 0.8 | 3.0 | −0.5 | 1.1 | 25 | n.a. | n.a. |

| Lithuania | 0.3 | 32 | 38 | −0.9 | 7.0 | 0.1 | 8.2 | 60 | 1.0 | −1.0 |

| Malaysia | 0.4 | 31 | 17 | −0.1 | 4.5 | 1.1 | 7.2 | 26 | −0.7 | 0.1 |

| Morocco | −0.2 | 35 | 17 | 0.5 | 2.8 | −0.0 | 2.3 | 46 | −1.3 | −1.0 |

| Netherlands | 2.1 | 13 | 40 | −2.9 | 7.0 | 2.1 | 23.7 | 80 | 0.7 | 1.4 |

| Poland | 0.4 | 28 | 37 | −1.1 | 6.4 | 0.6 | 7.6 | 60 | −0.8 | −0.1 |

| Slovakia | 0.3 | 18 | 36 | −1.4 | 6.4 | 0.6 | 9.7 | 52 | 0.7 | −0.4 |

| South Africa | 0.3 | 28 | 36 | −1.0 | 7.0 | 0.7 | 6.0 | 65 | −1.1 | −0.1 |

| Spain | 1.4 | 22 | 39 | −2.0 | 7.0 | 1.8 | 17.6 | 51 | 0.1 | 0.5 |

| Sweden | 2.2 | 19 | 40 | −2.8 | 7.0 | 2.0 | 21.1 | 71 | 1.9 | 2.4 |

| Tanzania | −0.8 | 57 | 22 | 1.6 | 3.0 | −0.4 | 0.7 | 25 | −1.8 | −0.2 |

| Turkey | −0.2 | 32 | 24 | 0.0 | 7.0 | 0.0 | 6.8 | 37 | −0.9 | −0.3 |

| U. Kingdom | 2.1 | 13 | 40 | −2.9 | 7.0 | 1.9 | 20.2 | 89 | 0.1 | 1.7 |

| Vietnam | −0.5 | 15 | 2 | 0.5 | 3.0 | −0.4 | 1.0 | 20 | −0.3 | −0.3 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Sample Mean | 0.4 | 28 | 28 | −0.7 | 5.5 | 0.5 | 9.9 | 46 | −0.1 | 0.1 |

|

| ||||||||||

| World Mean | 0.0 | 33 | 24 | 0.0 | 4.5 | −0.0 | 7.8 | 39 | −0.3 | 0.0 |

| World Min | −1.8 | 9 | −2 | −3.1 | 1.0 | −2.3 | 0.3 | 6 | −2.1 | −1.7 |

| World Max | 2.5 | 68 | 44 | 2.8 | 7.0 | 2.2 | 41.7 | 91 | 2.0 | 2.3 |

| World N | 199 | 161 | 192 | 159 | 161 | 196 | 183 | 102 | 94 | 94 |

Extended Data Table 2.

Regression analysis of societal and individual determinants of dishonesty

The explanatory variables are the scores of a country's Prevalence of Rule Violations in 2003; participants' individual norms of honesty (based on individual opinions about justifiableness of various acts of cheating; higher scores indicate stronger norms); participants' beliefs in fairness (the perceived fairness of most others; a higher score indicates a higher belief). Socio-demographic controls include age; dummies for sex, urban residency, middle class status, being an economics student, and being religious; and the percentage of other participants known to a participant. Detailed data description and rationale are in the Supplementary Methods. Chi2-tests reveal that socio-demographic controls are jointly insignificant in all models except model (2), where they are weakly significant. The estimation method is OLS with bootstrapped standard errors clustered on countries. The results are robust to various specifications (Supplementary Analysis).

| (1) Claim | (2) High Claim (Numbers 3, 4, 5) | (3) Highest Claim (Number 5) | (4) No Claim (Number 6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRV in 2003 | 0.115*** (0.033) | 0.030*** (0.007) | 0.012 (0.010) | −0.016*** (0.005) |

| Individual norms of honesty | −0.055*** (0.018) | −0.012*** (0.004) | −0.014** (0.006) | 0.002 (0.002) |

| Individual beliefs in fairness of others | −0.075 (0.085) | −0.012 (0.030) | −0.050** (0.021) | −0.004 (0.009) |

| Age | −0.005 (0.011) | −0.002 (0.003) | 0.003 (0.004) | 0.002 (0.001) |

| Female | −0.108* (0.058) | −0.020 (0.016) | −0.019 (0.020) | 0.014 (0.012) |

| Middleclass | −0.064 (0.106) | −0.021 (0.033) | −0.001 (0.022) | 0.002 (0.018) |

| Urban | −0.052 (0.055) | −0.027 (0.016) | −0.013 (0.014) | −0.006 (0.013) |

| Economic Student | 0.122 (0.099) | 0.042 (0.028) | −0.009 (0.032) | −0.023 (0.016) |

| Religious | −0.061 (0.090) | −0.030 (0.022) | 0.023 (0.023) | 0.018 (0.014) |

| % known in session | 0.004 (0.003) | 0.001 (0.001) | 0.002** (0.001) | 0.000 (0.001) |

| Constant | 4.080*** (0.315) | 0.925*** (0.073) | 0.376*** (0.112) | −0.006 (0.044) |

|

| ||||

| Test for joint significance of Socio-demographic controls | Chi2(7)=9.18 | Chi2(7)=12.37* | Chi2(7)=6.42 | Chi2(7)=11.88 |

|

| ||||

| N | 2284 | 2284 | 2284 | 2284 |

| R2 | 0.022 | 0.018 | 0.014 | 0.010 |

P < 0.10,

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01.

Extended Data Table 3.

Institutional and Cultural Determinants of PRV

Dependent variable is PRV in 2003. Our approach follows recent advances in the economic literature on institutions and culture (see Supplementary Analysis for details and references). Models (1) to (6) are OLS; models (7) to (10) use instrumental variables to identify causal relations. All regressions control for legal origin (French, British, German, Scandinavian). Model (1) shows that both a frequently used measure for institutional quality (Constraint on Executive) and a frequently used measure for culture (Individualism) are significantly correlated with PRV. Model (2) shows that past institutional quality (Constraint on Executive in 1890-1900) can have long-lasting effects on PRV. Models (3) to (6) control for important variables proposed in the literature. Models (7) to (10) report the results from instrumental variable estimation (instrumented variables are in bold); the instruments are assumed to have no direct impact on PRV but only on the explanatory variable and thereby allow identifying a causal effect of either institutions (as measured by Constraint on Executive) or culture (as measured by Individualism) on PRV. Model (7) instruments institution with ‘settler mortality’ in European colonies (1600-1875). To preserve degrees of freedom we do not include Individualism. Model (8) uses language (grammatical rules) and model (9) genetic distance as an instrument for culture. Model (10) uses both instruments. Models (7) to (10) suggest causal effects of both the quality of institutions and culture (Individualism) on PRV.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) IV: Sett. Mortality |

(8) IV: Gram. Rule |

(9) IV: Gen. Dist. |

(10) IV: Gen. Dist. + Gram. Rule |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Const. on Executive (1990 to 2000) |

−0.25*** (0.05) | −0.23*** (0.07) | −0.21*** (0.05) | −0.09*** (0.03) | −0.25*** (0.05) | −0.72*** (0.12) | −0.25** (0.11) | −0.23*** (0.08) | −0.25** (0.11) | |

| Individualism | −0.03*** (0.00) | −0.03*** (0.01) | −0.02*** (0.01) | −0.02*** (0.00) | −0.01** (0.00) | −0.03*** (0.00) | −0.06* (0.03) | −0.05** (0.03) | −0.06** (0.03) | |

| Const. on Executive (1890 to 1900) |

−0.26*** (0.06) | |||||||||

| Primary Education (1930) |

−0.02*** (0.00) | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.00 (0.02) | 0.01 (0.02) | ||||||

| GDP p. capita (PPP in $ 1000) |

−0.07*** (0.01) | |||||||||

| Gov. Effectiveness (2000) |

−1.10*** (0.07) | |||||||||

| Ethnolinguistic Fractionalization |

0.41 (0.38) | |||||||||

| Constant | 2.14*** (0.26) | 1.67*** (0.17) | 2.20*** (0.30) | 2.02*** (0.22) | 0.59*** (0.19) | 1.91*** (0.33) | 3.79*** (0.53) | 2.69*** (0.56) | 2.67*** (0.51) | 2.68*** (0.51) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Controls for Legal Origin | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

|

| ||||||||||

| N | 96 | 44 | 79 | 96 | 96 | 96 | 60 | 59 | 79 | 59 |

| R2 | 0.681 | 0.810 | 0.785 | 0.824 | 0.904 | 0.685 | 0.131 | 0.633 | 0.673 | 0.652 |

| 1st-stage F-stat | 12.4*** | 60.3*** | 51.7*** | 68.4*** | ||||||

| Overid test p-value | 0.907 | |||||||||

P < 0.10,

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Arechar, A. Barr, B. Beranek, M. Eberhardt, E. von Essen, E. Fehr, U. Fischbacher, M. García-Vega, B. Herrmann, F. Kölle, L. Molleman, D. Rand, K. Schmelz, S. Shalvi, P. Thiemann, C. Thöni, O. Weisel, and seminar audiences for helpful comments. Support under ERC-AdG 295707 COOPERATION and the ESRC Network on Integrated Behavioural Science (NIBS, ES/K002201/1) is gratefully acknowledged. We thank numerous helpers (Supplementary Information) for their support in implementing the experiments.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is available in the online version of the paper.

The data and code for the statistical analyses are stored in Dryad Data package title: Intrinsic Honesty across Societies; http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.9k358.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Trivers RL. Deceit and self-deception. Fooling yourself the better to fool others. Penguin, London: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gino F, Ayal S, Ariely D. Contagion and differentiation in unethical behavior: the effect of one bad apple on the barrel. Psychological Science. 2009;20:393. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keizer K, Lindenberg S, Steg L. The spreading of disorder. Science. 2008;322:1681. doi: 10.1126/science.1161405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hauk E, Saez-Marti M. On the cultural transmission of corruption. Journal of Economic Theory. 2002;107:311. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fischbacher U, Föllmi-Heusi F. Lies in disguise—an experimental study on cheating. Journal of the European Economic Association. 2013;11:525. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mazar N, Amir O, Ariely D. The dishonesty of honest people: a theory of self-concept maintenance. Journal of Marketing Research. 2008;45:633. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shalvi S, Dana J, Handgraaf MJJ, De Dreu CKW. Justified ethicality: observing desired counterfactuals modifies ethical perceptions and behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 2011;115:181. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowles S. Is liberal society a parasite on tradition? Philosophy & Public Affairs. 2011;39:46. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greif A. Cultural beliefs and the organization of society: a historical reflection on collectivist and individualist societies. Journal of Political Economy. 1994;102:912. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazar N, Aggarwal P. Greasing the palm: can collectivism promote bribery? Psychological Science. 2011;22:843. doi: 10.1177/0956797611412389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hruschka D, et al. Impartial institutions, pathogen stress and the expanding social network. Human Nature. 2014;25:567. doi: 10.1007/s12110-014-9217-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Besley T, Persson T. Pillars of prosperity. The political economics of development clusters. Princeton University Press; Princeton: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heywood PM, editor. Routledge Handbook of Political Corruption. Routledge; London and New York: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tabellini G, Institutions and culture Journal of the European Economic Association. 2008;6:255. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henrich J, Boyd R. The evolution of conformist transmission and the emergence of between-group differences. Evolution and Human Behavior. 1998;19:215. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Houser D, Vetter S, Winter J. Fairness and cheating. European Economic Review. 2012;56:1645. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gintis H, Khurana R. In: Moral markets. The critical role of values in the economy. Zak PJ, editor. Princeton University Press, Princeton; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crittenden V, Hanna R, Peterson R. Business students’ attitudes toward unethical behavior: a multi-country comparison. Marketing Letters. 2009;20:1. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohn A, Fehr E, Marechal MA. Business culture and dishonesty in the banking industry. Nature. 2014;516:86. doi: 10.1038/nature13977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weisel O, Shalvi S. The collaborative roots of corruption. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2015;112:10651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423035112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henrich J, Gil-White FJ. The evolution of prestige: freely conferred deference as a mechanism for enhancing the benefits of cultural transmission. Evolution and Human Behavior. 2001;22:165. doi: 10.1016/s1090-5138(00)00071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lefebvre M, Pestieau P, Riedl A, Villeval M. Tax evasion and social information: an experiment in Belgium, France, and the Netherlands. International Tax and Public Finance. 2015;22:401. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tabellini G. The scope of cooperation: values and incentives. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2008;123:905. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barr A, Serra D. Corruption and culture: an experimental analysis. Journal of Public Economics. 2010;94:862. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kimbrough EO, Vostroknutov A. Norms make preferences social. Journal of the European Economic Association. 2015 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peysakhovich A, Rand DG. Habits of virtue: creating norms of cooperation and defection in the laboratory. Management Science. 2015 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gneezy U. Deception: The role of consequences. American Economic Review. 2005;95:384. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abeler J, Becker A, Falk A. Representative evidence on lying costs. Journal of Public Economics. 2014;113:96. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pascual-Ezama D, et al. Context-dependent cheating: experimental evidence from 16 countries. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 2015;116:379. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenbaum SM, Billinger S, Stieglitz N. Let’s be honest: a review of experimental evidence of honesty and truth-telling. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2014;45:181. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.