Abstract

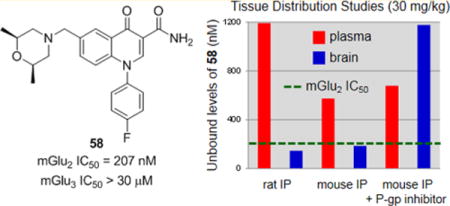

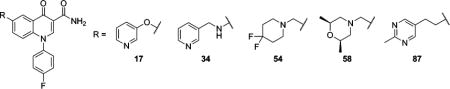

Both orthosteric and allosteric antagonists of the group II metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGlus) have been used to establish a link between mGlu2/3 inhibition and a variety of CNS diseases and disorders. Though these tools typically have good selectivity for mGlu2/3 versus the remaining six members of the mGlu family, compounds that are selective for only one of the individual group II mGlus have proved elusive. Herein we report on the discovery of a potent and highly selective mGlu2 negative allosteric modulator 58 (VU6001192) from a series of 4-oxo-1-aryl-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxamides. The concept for the design of this series centered on morphing a quinoline series recently disclosed in the patent literature into a chemotype previously used for the preparation of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor subtype 1 positive allosteric modulators. Compound 58 exhibits a favorable profile and will be a useful tool for understanding the biological implications of selective inhibition of mGlu2 in the CNS.

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

Glutamate (L-glutamic acid) is the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the mammalian central nervous system (CNS) and exerts its effects through both ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGlus). The mGlus belong to family C of the G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and are characterized by a seven-transmembrane (7TM) α-helical domain connected via a cysteine-rich region to a large bi-lobed extracellular amino-terminal domain. The orthosteric binding site is found within this amino-terminal domain for each of the eight members of the mGlu family. The mGlus are further categorized into three groups according to their homology, preferred signal transduction mechanisms, and pharmacology. The group I mGlus (mGlu1 and mGlu5) are primarily located postsynaptically in neurons and coupled via Gq to the activation of phospholipase C, which leads to the elevation of intracellular calcium and activation of protein kinase C (PKC). On the other hand, group II mGlus (mGlu2 and mGlu3) and group III mGlus (mGlu4, mGlu6, mGlu7, and mGlu8) are primarily located presynaptically and are coupled via Gi/o to the inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity.1–3The expression of the group II mGlus is wide throughout the CNS; moreover, both are found in brain regions associated with emotional states such as the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex.4,5

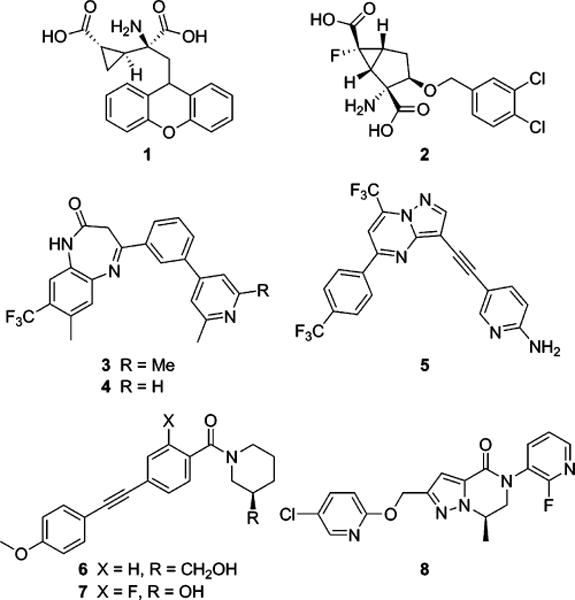

With multiple compounds having advanced into clinical trials in schizophrenic patients, the design of selective and druglike positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) of mGlu2 is significantly more advanced than complementary research directed toward selective negative allosteric modulators (NAMs) of the same receptor.6 Still, the literature contains multiple examples of highly optimized orthosteric antagonists and NAMs of the group II mGlus. Though these compounds typically possess good levels of selectivity against the other members of the mGlu family, they lack appreciable selectivity between mGlu2 and mGlu3.7 Consequently, much has been learned regarding the potential utility of group II mGlu inhibition through the use of these tools in animal models of various CNS disorders. The bulk of such studies have employed the two orthosteric antagonists 1 (LY341495)8 and 2 (MGS0039)9 (Figure 1). Specifically, potential therapeutic applications of group II mGlu antagonists have been established in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD),10,11 anxiety,12 cognition,13 and Alzheimer’s disease.14–16 Additionally, substantial work with these compounds has been directed toward establishing a role for mGlu2/3 antagonists as novel antidepressants.9,10,12,17–22 Perhaps most intriguing are studies demonstrating efficacy in animal models of treatment-resistant depression (TRD)23 and anhedonia.24

Figure 1.

mGlu2/3 orthosteric antagonist tools 1 and 2, mGlu2/3 NAM tools 3 and 4, Roche mGlu2/3 NAM clinical compound 5, first-generation selective mGlu3 NAMs 6 and 7, and mGlu3 NAM in vivo tool 8.

Reports of in vivo studies with mGlu2/3 NAMs are less prevalent; yet two related compounds from a series of 4-aryl-1,3-dihydro-2H-benzo[b][1,4]diazepin-2-ones, 3 (RO4491533)25 and 4 (RO4432717)26,27 (Figure 1) are worth noting. Studies in rodent models of depression25,28 and cognition27,29,30 with these tools have been disclosed and show similar results as those observed with mGlu2/3 orthosteric antagonists. Additionally, another structurally distinct mGlu2/3 NAM, 5 (decoglurant, RO4995819)31 from Roche (Figure 1), advanced into a phase II trial in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) (NCT01457677).32 Thus, the evidence for a therapeutic application with mGlu2/3 antagonists is compelling; however, further elucidation is required regarding the individual importance of mGlu2 and mGlu3 in these various disorders. As such, we have been pursuing the design of selective antagonists of each receptor for use as in vivo tools. Our initial success came in the design of selective mGlu3 NAMs from a series of 1,2-diphenylethyne compounds represented by tool compounds 6 (VU0463597, ML289)33 and 7 (VU0469942, ML337)34,35 (Figure 1). More recently we reported on another mGlu3 NAM, 8 (VU0650786),36 that is a superior in vivo tool and has demonstrated efficacy in rodent models of anxiety/OCD and depression.36 Having selective mGlu3 NAMs from multiple chemotypes in hand, we sought strategies for the design of selective mGlu2 NAMs for the purpose of thoroughly evaluating the therapeutic potential of each individual target. Our first successful execution of such a strategy is described in this manuscript.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Scaffold Design

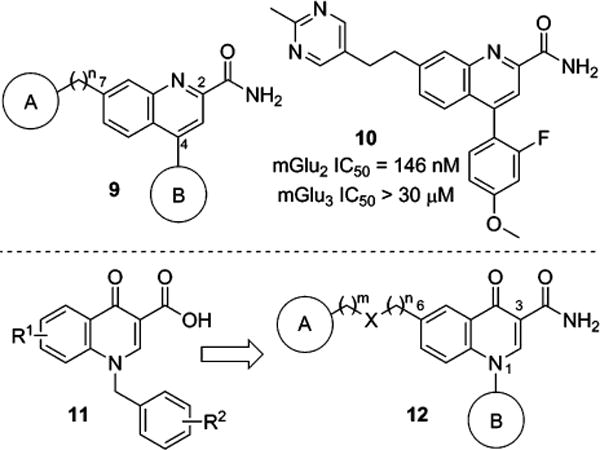

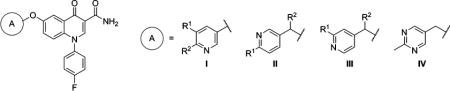

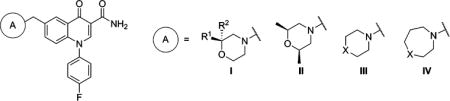

In our search for new scaffolds suitable for the design of selective mGlu2 NAMs, we were intrigued by a set of quinoline-2-carboxamide compounds 9 developed at Merck and disclosed in the patent literature (Figure 2).7,37 A survey of the functional mGlu2 NAM activity presented in this application showed substantial tolerance for functional diversity at the 7-position with a variety of linkers connected to a number of unsaturated and saturated ring systems (A). The 4-position demonstrated a preference for aryl and heteroaryl rings (B), and a primary amide was preferred over a nitrile at the 2-position. We prepared an exemplar compound 10 and tested it in our own cell-based functional assays for mGlu2 and mGlu3.35 These fluorescence-based assays measure calcium mobilization induced by receptor activation in a cell line stably expressing either rat mGlu2 or rat mGlu3 along with the promiscuous G-protein Gα15 and are capable of detecting agonists, PAMs, and NAMs. Compound 10 exhibited potent NAM activity at mGlu2 and no evidence of mGlu3 activity up to the highest concentration tested (30 μM). The quinoline-2-carboxamide mGlu2 NAMs were reminiscent of another series of allosteric modulators developed at Merck, the 4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylic acid muscarinic acetylcholine receptor subtype 1 (M1) PAMs 11.38–40 Our hypothesis was that a new mGlu2 NAM scaffold 12 might be obtained within a 4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline series by appending appropriately linked groups (A) at the 6-position and installing N-aryl rings (B) at the 1-position in the context of a primary amide at the 3-position. In addition, the extensive M1 PAM SAR already developed in this chemotype indicated that such changes would not be favorable for that target.

Figure 2.

Merck quinoline-2-carboxamide mGlu2 NAM scaffold 9 and representative compound 10; Merck 4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylic acid M1 PAM scaffold 11; proposed 4-oxo-1-aryl-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxamide mGlu2 NAM scaffold 12.

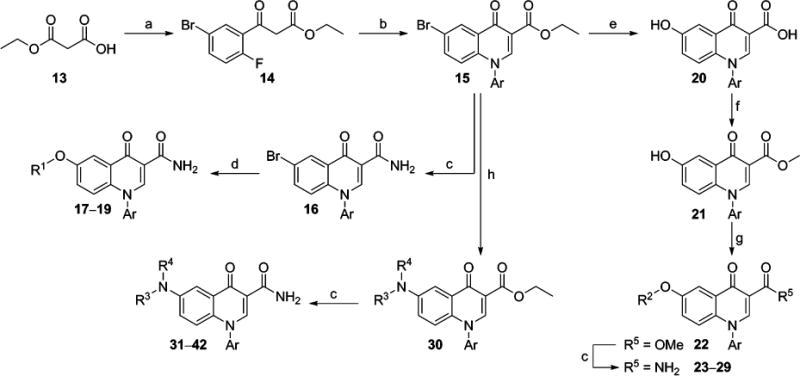

Synthesis of Compounds

It was envisioned that a number of interesting analogs could be prepared from versatile 6-bromo intermediate 15 (Scheme 1). The synthesis began with commercially available acid 13. Treatment of 13 with 2 equiv of butyllithium followed by addition of 5-bromo-2-fluorobenzoyl chloride provided β-ketoester 14. Reaction of 14 with N,N-dimethylformamide dimethyl acetal followed by a suitable arylamine under microwave heating afforded the desired intermediate 15. Compound 15 could be converted to primary amide 16 through heating in ammonia in methanol under microwave irradiation to give 16. Where possible, 16 was used as a common intermediate; however, certain transformations proved incompatible with the primary amide functional group and necessitated the use of ester 15 with subsequent conversion to the primary amide at a later stage. Reaction of 16 with commercially available aryl alcohols (R1OH) in the presence of copper(I) iodide and dimethylglycine provided aryl ether analogs 17–19 (Table 1). For synthesis of ethers 23–29 (Table 1), conversion of bromide 15 to alcohol 20 was accomplished with a palladium catalyzed hydroxylation.41 Acid 20 was converted to methyl ester 21 via a Fischer esterification. A Mitsunobu coupling42 with commercial alcohols (R2OH) was employed for installation of the various 6-substituted ethers to afford 22. Conversion of the ester moieties to the corresponding primary amides to yield 23–29 was carried out as described previously. Finally, the synthesis of amine analogs 31–42 (Table 2) was accomplished by first reacting bromide 15 with commercially available amines in a Buchwald–Hartwig amination reaction43 to yield 30. Conversion of 30 to analogs 31–42 was carried out as described previously.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of 6-Heteroatom Linked Analogsa.

aReagents and conditions: (a) n-BuLi, 2,2′-bipyridyl, −30 °C to −5 °C, then 5-bromo-2-fluorobenzoyl chloride, −78 °C to −30 °C, 67%; (b) N,N-dimethylformamide dimethyl acetal, DMF, microwave, 120 °C, 15 min, then ArNH2, microwave, 150 °C, 20 min, 60–98%; (c) 7 N NH3 in MeOH, microwave, 150 °C, 60 min, 29–99%; (d) R1OH, CuI, Cs2CO3, Me2NCH2CO2H, microwave, 150 °C, 15 min, 26–56% (e) KOH, Pd2(dba)3, t-BuXphos, dioxane, H2O, microwave, 150 °C, 15 min, 99%; (f) MeOH, conc H2SO4, reflux, 74%; (g) R2OH, PPh3, DtBAD, THF, 40–98%; (h) HNR3R4, Pd2(dba)3, Xantphos, Cs2CO3, PhMe, 110 °C, 8–54%.

Table 1.

mGlu2 NAM and in Vitro DMPK Results with 6-Substituted Ethers

| ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | A | R1 | R2 | mGlu2 pIC50 ± SEMa | mGlu2 IC50 (nM)a | % Glu max ± SEMa,b | cLogPc | LLEd | rat plasma fue | rat CLhep (mL min−1 kg−1)f |

| 17 | I | H | H | 6.07 ± 0.09 | 850 | 1.84 ± 0.47 | 2.80 | 3.27 | 0.083 | 40.6 |

| 18 | I | F | H | 5.89 ± 0.07 | 1280 | 0.87 ± 0.15 | 2.90 | 2.99 | ||

| 19 | I | H | F | 6.05 ± 0.12 | 887 | 1.20 ± 0.29 | 3.31 | 2.74 | ||

| 23 | II | H | H | 6.05 ± 0.07 | 895 | 1.63 ± 0.33 | 2.92 | 3.13 | ||

| 24 | II | Me | H | 6.29 ± 0.10 | 515 | 1.55 ± 0.39 | 3.11 | 3.18 | 0.056 | 43.0 |

| 25 | II | H | Me | 6.41 ± 0.05 | 386 | 1.31 ± 0.45 | 3.42 | 2.99 | 0.072 | 64.2 |

| 26 | III | H | H | 6.05 ± 0.07 | 895 | 1.63 ± 0.33 | 2.92 | 3.13 | ||

| 27 | III | Me | H | 6.39 ± 0.09 | 403 | 1.09 ± 0.16 | 3.11 | 3.28 | 0.091 | 58.0 |

| 28 | III | H | Me | 6.35 ± 0.06 | 450 | 1.07 ± 0.13 | 3.42 | 2.93 | 0.061 | 63.6 |

| 29 | IV | 6.14 ± 0.06 | 723 | 1.30 ± 0.58 | 2.73 | 3.41 | ||||

Calcium mobilization mGlu2 assay; values are average of n ≥ 3.

Amplitude of response in the presence of 30 μM test compound as a percentage of maximal response (100 μM glutamate); average of n ≥ 3.

Calculated using Dotmatics Elemental (www.dotmatics.com/products/elemental/)

LLE (ligand-lipophilicity efficiency) = pIC50 – cLogP.

fu = fraction unbound.

Predicted hepatic clearance based on intrinsic clearance (CLint) in rat liver microsomes.

Table 2.

mGlu2 NAM and in Vitro DMPK Results with 6-Substituted Amines

| ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | A | X | R | mGlu2 pIC50 ± SEMa | mGlu2 IC50 (nM)a | % Glu max ± SEMa,b | cLogPc | LLEd | rat plasma fue | rat CLhep (mL min−1 kg−1)f |

| 31 | I | H | 6.48 ± 0.12 | 328 | 2.11 ± 0.42 | 2.57 | 3.91 | 0.084 | 48.2 | |

| 32 | I | Me | 6.50 ± 0.37 | 318 | −0.65 ± 1.98 | 2.95 | 3.55 | 0.061 | 60.4 | |

| 33 | II | Me | 6.06 ± 0.06 | 874 | 1.16 ± 0.55 | 2.95 | 3.11 | |||

| 34 | I | CH2 | H | 6.47 ± 0.10 | 341 | 1.38 ± 0.58 | 2.61 | 3.86 | 0.137 | 51.3 |

| 35 | I | CH2 | Me | 6.70 ± 0.03 | 201 | 2.39 ± 0.13 | 2.92 | 3.78 | 0.082 | 67.6 |

| 36 | I | CH2 | Et | 6.80 ± 0.01 | 159 | 2.36 ± 0.14 | 3.33 | 3.47 | 0.067 | 68.2 |

| 37 | II | CH2 | Me | 6.70 ± 0.09 | 201 | 1.76 ± 0.74 | 2.92 | 3.78 | 0.089 | 67.0 |

| 38 | III | CH2 | Me | 6.83 ± 0.09 | 147 | 1.86 ± 0.26 | 2.74 | 4.09 | 0.340 | 47.1 |

| 39 | IV | CH2 | H | 6.27 ± 0.05 | 535 | 1.15 ± 0.47 | 2.87 | 3.40 | ||

| 40 | I | CH2CH2 | H | 6.53 ± 0.12 | 296 | 1.98 ± 0.67 | 2.71 | 3.82 | 0.037 | 63.8 |

| 41 | II | CH2CH2 | H | 6.42 ± 0.11 | 376 | 2.01 ± 0.40 | 2.71 | 3.71 | 0.172 | 60.5 |

| 42 | V | CH2CH2 | H | 6.09 ± 0.07 | 816 | 1.13 ± 0.18 | 1.56 | 4.53 | ||

Calcium mobilization mGlu2 assay; values are average of n ≥ 3.

Amplitude of response in the presence of 30 μM test compound as a percentage of maximal response (100 μM glutamate); average of n ≥ 3.

Calculated using Dotmatics Elemental (www.dotmatics.com/products/elemental/).

LLE (ligand-lipophilicity efficiency) = pIC50 – cLogP.

fu = fraction unbound.

Predicted hepatic clearance based on intrinsic clearance (CLint) in rat liver microsomes.

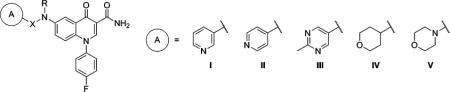

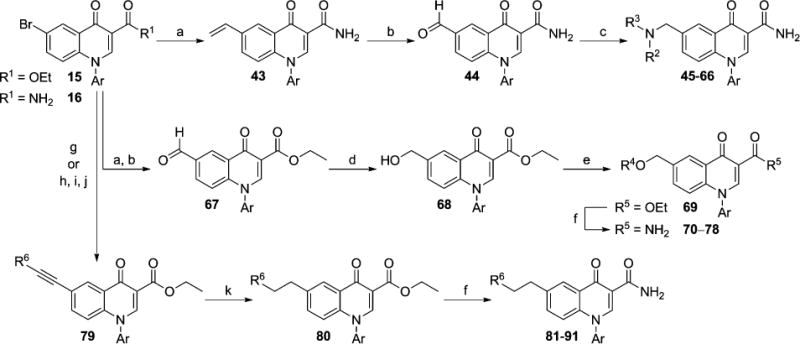

In addition to the 6-heteroatom linked analogs, 6-carbon linked compounds were prepared from intermediates 15 and 16 (Scheme 2). Methylene-linked tertiary amine analogs 45–66 (Tables 3 and 4) were accessed through bromide 16, which was first converted to vinyl intermediate 43 via a Suzuki coupling with potassium vinyltrifluoroborate.44 Dihydroxylation of the olefin and subsequent in situ periodate cleavage of the resultant diol gave aldehyde 44. Analogs 45–66 were then prepared through reductive aminations with 44 and commercially available secondary amines (HNR2R3). For preparation of methyleneoxy linked analogs 70–78 (Table 5), bromide 15 was converted to aldehyde 67 via an analogous vinylation, dihydroxylation, and periodate cleavage as described above. Sodium borohydride reduction of 67 gave primary alcohol 68, which was reacted in a Mitsunobu coupling42 with commercial alcohols (R4OH) to give ether intermediate 69. Conversion of the ester moieties to the corresponding primary amides to yield 70–78 was carried out as described previously. Ethylene linked analogs 81–91 (Table 6 and Table 7) were also prepared from bromide 15 through initial preparation of alkynes 79. Two methods were employed for preparation of these alkyne intermediates 79, each relying on Sonogashira couplings45 with bromide 15. A coupling with 15 and a terminal alkyne (R6CCH) gave 79 directly. Alternatively, a coupling with trimethylsilylacetylene followed by fluoride mediated silyl cleavage gave a 6-alkyne intermediate that was coupled to an aryl bromide (R6Br) to afford 79. A palladium catalyzed hydrogenation of the alkyne moiety provided 80, which was reacted with ammonia as described previously to yield the target compounds 81–91.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of 6-Carbon Linked Analogsa.

aReagents and conditions: (a) H2CCHBF3K, Pd(dppf)·CH2Cl2, NEt3, n-propanol, 100 °C, 75–100%; (b) OsO4, NMO, acetone, H2O, then NaIO4, 91–99%; (c) HNR2R3, NaBH(OAc)3, AcOH, CH2Cl2, 7–81%; (d) NaBH4, EtOH, 0 °C, 36–57%; (e) R4OH, PPh3, DtBAD, THF, 14–98%; (f) 7 N NH3 in MeOH, microwave, 150 °C, 15 min, 10–94%; (g) R6CCH, PdCl2(PPh3)2, CuI, NEt3, DMF, microwave, 150 °C, 15 min, 23–54%; (h) Me3SiCCH, PdCl2(PPh3)2, CuI, NEt3, DMF, microwave, 150 °C, 15 min, 83%; (i) TBAF, THF, 70%; (j) R6Br, PdCl2(PPh3)2, CuI, NEt3, DMF, microwave, 150 °C, 15 min, 21–47%; (k) 10% Pd/C, MeOH, H2 (1 atm), 63–99%.

Table 3.

mGlu2 NAM and in Vitro DMPK Results with 6-Substituted Methylene Amines

| ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | A | R1 | R2 | mGlu2 pIC50 ± SEMa | mGlu2 IC50 (nM)a | % Glu max ± SEMa,b | cLogPc | LLEd | rat plasma fue | rat CLhep (mL min−1 kg−1)f |

| 45 | I | 6.40 ± 0.01 | 396 | 1.16 ± 0.18 | 3.86 | 2.54 | 0.138 | 60.9 | ||

| 46 | II | 5.66 ± 0.09 | 2170 | 0.43 ± 0.75 | 4.09 | 1.57 | ||||

| 47 | III | 5.75 ± 0.06 | 1770 | 1.44 ± 0.30 | 3.39 | 2.36 | ||||

| 48 | IV | 6.67 ± 0.09 | 214 | 1.10 ± 0.12 | 3.32 | 3.35 | 0.156 | 56.5 | ||

| 49 | V | H | H | <5.0g | >10000 | 37.2 ± 9.7 | 3.55 | <1.45 | ||

| 50 | V | H | CF3 | 6.21 ± 0.09 | 618 | 1.11 ± 0.28 | 4.21 | 2.00 | ||

| 51 | V | H | CN | 6.23 ± 0.07 | 587 | 0.90 ± 0.33 | 2.94 | 3.29 | ||

| 52 | V | H | OMe | 5.77 ± 0.11 | 1720 | 1.03 ± 0.26 | 3.08 | 2.69 | ||

| 53 | V | H | SO2Me | 6.05 ± 0.09 | 886 | 1.36 ± 0.26 | 2.34 | 3.71 | ||

| 54 | V | F | F | 6.79 ± 0.19 | 161 | 1.59 ± 0.27 | 3.77 | 3.02 | 0.109 | 48.6 |

Calcium mobilization mGlu2 assay; values are average of n ≥ 3.

Amplitude of response in the presence of 30 μM test compound as a percentage of maximal response (100 μM glutamate); average of n ≥ 3.

Calculated using Dotmatics Elemental (www.dotmatics.com/products/elemental/).

LLE (ligand-lipophilicity efficiency) = pIC50 – cLogP.

fu = fraction unbound.

Predicted hepatic clearance based on intrinsic clearance (CLint) in rat liver microsomes.

Weak activity; concentration–response curve (CRC) does not plateau.

Table 4.

mGlu2 NAM and in Vitro DMPK Results with 6-Substituted Methylene Amines (Continued)

| |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | A | R1 | R2 | X | mGlu2 pIC50 ± SEMa | mGlu2 IC50 (nM)a | % Glu max ± SEMa,b | cLogPc | LLEd | rat plasma fue | rat CLhep (mL min−1 kg−1)f |

| 55 | I | Me | H | 6.47 ± 0.16 | 341 | 0.98 ± 0.24 | 2.59 | 3.88 | |||

| 56 | I | H | Me | 6.26 ± 0.16 | 551 | 1.33 ± 0.15 | 2.59 | 3.67 | |||

| 57 | I | Me | Me | 6.93 ± 0.09 | 119 | 2.14 ± 0.17 | 2.99 | 3.94 | 0.16 | 51.2 | |

| 58 | II | 6.69 ± 0.04 | 207 | 1.48 ± 0.29 | 3.10 | 3.59 | 0.306 | 24.5 | |||

| 59 | III | S | 6.38 ± 0.09 | 420 | 1.52 ± 0.63 | 2.76 | 3.62 | 0.205 | 59.6 | ||

| 60 | III | SO2 | 6.06 ± 0.08 | 870 | 1.33 ± 0.38 | 1.35 | 4.71 | ||||

| 61 | III | NMe | 5.95 ± 0.06 | 1110 | 1.15 ± 0.32 | 2.09 | 3.86 | ||||

| 62 | III | NCH2CF3 | 6.21 ± 0.07 | 612 | 1.10 ± 0.07 | 2.90 | 3.31 | ||||

| 63 | IV | CH2 | 5.68 ± 0.10 | 2080 | 0.55 ± 0.21 | 4.00 | 1.68 | ||||

| 64 | IV | O | <5.0g | >10000 | 24.2 ± 3.6 | 2.54 | <2.46 | ||||

| 65 | IV | S | 6.86 ± 0.10 | 138 | 2.19 ± 0.24 | 3.21 | 3.65 | 0.074 | 63.8 | ||

| 66 | IV | SO2 | 6.38 ± 0.06 | 415 | 1.24 ± 0.04 | 1.80 | 4.58 | 0.253 | 23.7 | ||

Calcium mobilization mGlu2 assay; values are average of n ≥ 3.

Amplitude of response in the presence of 30 μM test compound as a percentage of maximal response (100 μM glutamate); average of n ≥ 3.

Calculated using Dotmatics Elemental (www.dotmatics.com/products/elemental/).

LLE (ligand-lipophilicity efficiency) = pIC50 – cLogP.

fu = fraction unbound.

Predicted hepatic clearance based on intrinsic clearance (CLint) in rat liver microsomes.

Weak activity; CRC does not plateau.

Table 5.

mGlu2 NAM and in Vitro DMPK Results with 6-Aryloxymethyl Ethers

| ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | A | R1 | R2 | mGlu2 pIC50 ± SEMa | mGlu2 IC50 (nM)a | % Glu max ± SEMa,b | cLogPc | LLEd | rat plasma fue | rat CLhep (mL min−1 kg−1)f |

| 70 | I | F | H | 6.13 ± 0.06 | 746 | 0.31 ± 0.30 | 3.42 | 2.71 | ||

| 71 | I | H | F | 6.35 ± 0.10 | 443 | 1.13 ± 0.38 | 3.42 | 2.93 | ||

| 72 | I | H | Me | 6.61 ± 0.11 | 247 | 1.62 ± 0.23 | 3.11 | 3.50 | 0.087 | 43.9 |

| 73 | I | H | Cl | 6.71 ± 0.10 | 193 | 1.70 ± 0.12 | 3.94 | 2.77 | 0.033 | 52.1 |

| 74 | I | H | CF3 | 5.88 ± 0.04 | 1330 | 1.23 ± 0.02 | 3.83 | 2.05 | ||

| 75 | II | F | H | 6.64 ± 0.10 | 228 | 1.83 ± 0.20 | 3.02 | 3.62 | 0.063 | 59.8 |

| 76 | II | H | Me | 6.45 ± 0.09 | 351 | 1.90 ± 0.32 | 3.11 | 3.34 | 0.050 | 37.2 |

| 77 | II | H | CF3 | 6.31 ± 0.06 | 486 | 1.70 ± 0.14 | 3.83 | 2.48 | ||

| 78 | III | 6.56 ± 0.08 | 277 | 1.71 ± 0.20 | 2.73 | 3.83 | 0.109 | 22.4 | ||

Calcium mobilization mGlu2 assay; values are average of n ≥ 3.

Amplitude of response in the presence of 30 μM test compound as a percentage of maximal response (100 μM glutamate); average of n ≥ 3.

Calculated using Dotmatics Elemental (www.dotmatics.com/products/elemental/).

LLE (ligand-lipophilicity efficiency) = pIC50 – cLogP.

fu = fraction unbound.

Predicted hepatic clearance based on intrinsic clearance (CLint) in rat liver microsomes.

Table 6.

mGlu2 NAM and in Vitro DMPK Results with 6-Ethylene Linked Analogs

| ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | A | R1 | R2 | mGlu2 pIC50 ± SEMa | mGlu2 IC50 (nM)a | % Glu max ± SEMa,b | cLogPc | LLEd | rat plasma fue | rat CLhep (mL min−1 kg−1)f |

| 81 | I | 5.16 ± 0.09 | 6890 | 2.07 ± 1.38 | 4.65 | 0.21 | ||||

| 82 | II | H | 6.33 ± 0.09 | 471 | 1.88 ± 0.38 | 3.34 | 2.99 | 0.057 | 66.7 | |

| 83 | II | CF3 | 6.52 ± 0.09 | 304 | 0.88 ± 0.06 | 4.25 | 2.27 | 0.039 | 68.4 | |

| 84 | III | H | H | 6.33 ± 0.08 | 466 | 1.90 ± 0.11 | 3.34 | 2.99 | 0.062 | 64.1 |

| 85 | III | CF3 | H | 5.76 ± 0.03 | 1720 | 1.22 ± 0.14 | 4.25 | 1.51 | ||

| 86 | III | H | F | 5.93 ± 0.04 | 1170 | 0.80 ± 0.34 | 3.44 | 2.49 | ||

| 87 | IV | 6.67 ± 0.10 | 215 | 1.52 ± 0.26 | 3.16 | 3.51 | 0.157 | 46.9 | ||

Calcium mobilization mGlu2 assay; values are average of n ≥ 3.

Amplitude of response in the presence of 30 μM test compound as a percentage of maximal response (100 μM glutamate); average of n ≥ 3.

Calculated using Dotmatics Elemental (www.dotmatics.com/products/elemental/).

LLE (ligand-lipophilicity efficiency) = pIC50 – cLogP.

fu = fraction unbound.

Predicted hepatic clearance based on intrinsic clearance (CLint) in rat liver microsomes.

Table 7.

mGlu2 NAM and in vitro DMPK Results with Modified 1-Position Analogs

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | B | mGlu2 pIC50 ± SEMa | mGlu2 IC50 (nM)a | % Glu max ± SEMa,b | cLogPc | LLEd | rat plasma fue | rat CLhep (mL min−1 kg−1)f |

| 87 | I | 6.67 ± 0.10 | 215 | 1.52 ± 0.26 | 3.16 | 3.51 | 0.157 | 46.9 |

| 88 | II | 6.87g | 136g | 1.61g | 3.02 | 3.85 | 0.098 | 53.4 |

| 89 | III | 6.58 ± 0.09 | 266 | 1.30 ± 0.21 | 3.12 | 3.46 | 0.085 | 53.6 |

| 90 | IV | 6.70 ± 0.13 | 198 | 1.52 ± 0.38 | 3.12 | 3.58 | 0.159 | 60.5 |

| 91 | V | 6.38 ± 0.05 | 414 | 1.20 ± 0.50 | 2.66 | 3.72 | 0.220 | 41.9 |

Calcium mobilization mGlu2 assay; values are average of n ≥ 3.

Amplitude of response in the presence of 30 μM test compound as a percentage of maximal response (100 μM glutamate); average of n ≥ 3.

Calculated using Dotmatics Elemental (www.dotmatics.com/products/elemental/).

LLE (ligand-lipophilicity efficiency) = pIC50 – cLogP.

fu = fraction unbound.

Predicted hepatic clearance based on intrinsic clearance (CLint) in rat liver microsomes.

Value is average of n = 2.

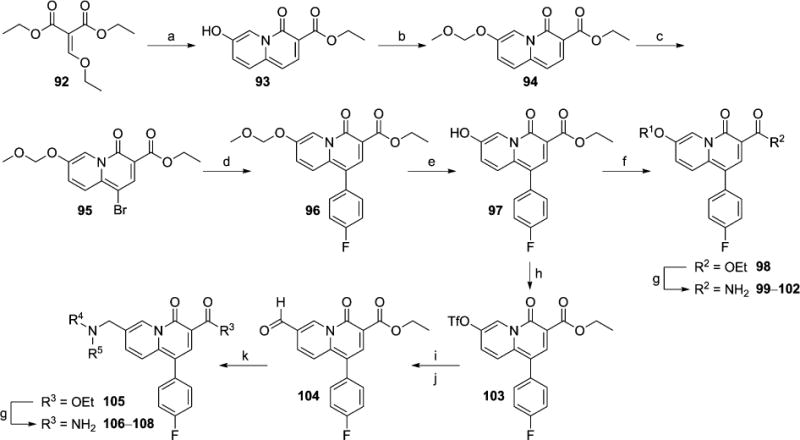

In the case of the aforementioned 4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylic acid M1 PAM scaffold, Merck has also shown that a 4H-quinolizin-4-one functioned as an effective bioisostere for the core of the chemotype.46–48 As such, we decided to prepare analogs with this core to evaluate its potential as an mGlu2 NAM scaffold as well (Scheme 3). The synthesis began with lithiation of 5-hydroxy-2-methylpyridine and subsequent in situ reaction with commercially available diethyl 2-(ethoxymethylene)malonate 92 to give 7-hydroxy-4-oxo-4H-quinolizine 93. The alcohol was protected as its methoxymethyl ether 94, which was then selectively brominated at the 1-position to afford 95. A Suzuki coupling with 4-fluorophenylboronic acid provided intermediate 96. Acidic cleavage of the protecting group and simple filtration of the precipitated product gave 97, which served as the key intermediate for the synthesis of analogs. Ether compounds 99–102 (Table 8) were prepared via Mitsunobu coupling42 with commercial alcohols (R1OH) to yield 98, which was converted to primary amides 99–102 as described above. Intermediate 97 was also converted to the corresponding triflate 103, which was subjected to an analogous vinylation, dihydroxylation, and periodate cleavage as described previously to afford aldehyde 104. Finally, conversion of 104 to amines 105 and ultimately final compounds 106–108 followed methods outlined herein above.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of 4H-Quinolizin-4-one Analogsa.

aReagents and conditions: (a) 5-hydroxy-2-methylpyridine, n-BuLi, THF, −78 °C to −30 °C, 57%; (b) CH3OCH2Cl, DIEA, CH2Cl2, 0 °C to rt, 96%; (c) NBS, CHCl3, 0 °C to rt, 96%; (d) 4-fluorophenylboronic acid, Pd(dppf)·CH2Cl2, 1 M aq Na2CO3, DME, 90 °C, 94%; (e) pTSA·H2O, EtOH, DCE, 80 °C, 66%; (f) R1OH, PPh3, DtBAD, THF, 0 to 45 °C, 38–82%; (g) 7 N NH3 in MeOH, microwave, 150 °C, 2.0–3.0 h, 26–90%; (h) PhN(SO2CF3)2, NEt3, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 96%; (i) H2CCHBF3K, Pd(dppf)·CH2Cl2, NEt3, n-propanol, 90 °C, 96%; (j) OsO4, NMO, THF, H2O, then NaIO4, 70%; (k) HNR4R5, NaBH(OAc)3, AcOH, CH2Cl2, 27–67%.

Table 8.

mGlu2 NAM Results with 4H-Quinolizin-4-one Analogs

| ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | A | X | Y | mGlu2 pIC50 ± SEMa | mGlu2 IC50 (nM)a | % Glu max ± SEMa,b | cLogPc | LLEd | comparatore | fold decrease in potencyf |

| 99 | I | O | C–H | 5.40 ± 0.02 | 3980 | 2.67 ± 0.26 | 2.83 | 2.57 | 24 | 5.8 |

| 100 | I | O | N | <5.0g | >10000 | 19.4 ± 9.3 | 2.45 | <2.55 | 29 | >13 |

| 101 | II | O | H | 5.27 ± 0.07 | 5360 | 0.71 ± 1.86 | 2.63 | 2.64 | 26 | 6.0 |

| 102 | II | O | CF3 | 5.34 ± 0.01 | 4610 | 2.19 ± 0.69 | 3.54 | 1.80 | ||

| 106 | III | CH2 | <5.0g | >10000 | 3.95 ± 1.84 | 2.65 | <2.35 | 58 | >48 | |

| 107 | IV | CH2 | 5.18 ± 0.13 | 6620 | 1.04 ± 2.27 | 2.77 | 2.41 | 65 | 48 | |

| 108 | V | CH2 | 5.36 ± 0.21 | 4400 | 0.93 ± 2.27 | 2.87 | 2.49 | 48 | 21 | |

Calcium mobilization mGlu2 assay; values are average of n ≥ 3.

Amplitude of response in the presence of 30 μM test compound as a percentage of maximal response (100 μM glutamate); average of n ≥ 3.

Calculated using Dotmatics Elemental (www.dotmatics.com/products/elemental/).

LLE (ligand-lipophilicity efficiency) = pIC50 – cLogP.

Direct comparator from 4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline series.

Fold decrease in potency relative to direct comparator from 4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline series.

Weak activity; CRC does not plateau.

mGlu2 NAM Activity and Preliminary DMPK SAR

As new analogs were evaluated for potency in our functional mGlu2 assay, interesting compounds were further assessed in our frontline in vitro drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics (DMPK) assays. Specifically, metabolic stability was determined by measuring the intrinsic clearance of the compound when incubated with rat liver microsomes (RLMs).49 The intrinsic clearance obtained was used to calculate a predicted hepatic clearance, and compounds were binned accordingly into low (<⅓ hepatic blood flow), moderate (⅓ to ⅔ hepatic blood flow) and high (>⅔ hepatic blood flow) groups. The extent to which the compounds were bound to rat plasma was also measured.50 We also calculated the lipophilicity of new analogs and attempted to assess the efficiency of the structural modifications being tested.51 Much of the SAR work was conducted in the context of a 4-fluorophenyl ring at the 1-position of the scaffold, as this was a group with good potency in the quinoline series, and it was likely to be somewhat metabolically stable. As expected, the mGlu2 NAM SAR with the new 4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline ether analogs showed a good deal of tolerance at the 6-position (Table 1). The ethers with directly linked heteroaryl rings (17–19) were among the least active in this set; however, in vitro DMPK was benchmarked. The fraction unbound in rat plasma with 17 was 0.083, and the predicted hepatic clearance was moderate. The remaining analogs 23–29 possessed a single sp3 hybridized carbon between the 6-position ether oxygen and the heteroaryl ring (A). This feature generally improved mGlu2 NAM activity. The methyl groups of analogs 24 and 25 both provided small boosts of potency relative to unsubstituted 3-pyridyl ring 23. Analogous 4-pyridyl methyl analogs 27 and 28 were approximately 2-fold more potent than unsubstituted comparator 26. Pyrimidine analog 29 was less potent than 3-pyridyl analog 24; however, installation of this nitrogen atom reduced lipophilicity, and the ligand-lipophilicity efficiency (LLE) of 29 indicated that this 2-methylpyrimidin-5-yl functional group was worthy of continued evaluation in other analogs. The compounds examined (24, 25, 27, 28) in our in vitro DMPK assays again had fraction unbound in rat plasma similar to 17, but only 24 had moderate predicted hepatic clearance with the remaining analogs having CLhep values near liver blood flow.

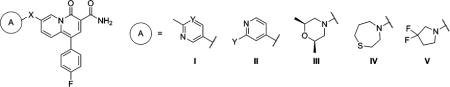

4-Oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline amine analogs further illustrated the tolerance for variation at the 6-position (Table 2). Additionally, many of these analogs exhibited superior mGlu2 NAM potency compared to the ether analogs discussed above. Simple alkylation of the nitrogen linker generally had minimal impact on mGlu2 NAM activity as evidenced by comparing secondary amine analogs 31 and 34 to their tertiary amine comparators 32, 35, and 36; however, in each case, the tertiary amine analogs exhibited a higher predicted hepatic clearance, possibly due to N-dealkylation. In the case of analogs with the ring (A) directly attached to the nitrogen linker, the 3-pyridyl ring (32) exhibited superior mGlu2 NAM activity compared to the 4-pyridyl ring (33). On the other hand, the difference in potency was minimal when a methylene (35 and 37) or ethylene spacer (40 and 41) was inserted between the nitrogen atom and the ring (A). Combining the methylene spacer with the 2-methylpyrimidin-5-yl ring (38) provided the most potent compound in this set. The fraction unbound was considerably higher with 38 relative to other similar analogs (35 and 37), and the predicted hepatic clearance, though still high, was less than the majority of the other analogs in this set. Though analogs 39 and 42 were not among the most potent amine analogs, these derivatives demonstrated that saturated heteroaryl rings were also tolerated at the 6-position of the chemotype.

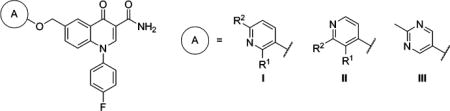

Having observed that aromatic rings were not required at the 6-position, we were interested to evaluate the numerous methylene amine analogs prepared at that position. Several of these analogs were simple tertiary amines without additional heteroatoms in the ring system (Table 3). The mGlu2 NAM activity observed with these compounds was generally more dependent on minor structural changes than had been observed with previous compounds. For example, difluorocyclobutylamine 45 was approximately 5-fold more potent than cyclopentylamine 46, and difluoropyrrolidine 48 was approximately 8-fold more potent than difluoroazaspiroheptane 47. Likewise, though unsubstituted piperidine 49 was only a weak mGlu2 NAM, inhibiting the glutamate response only at the highest concentration (30 μM), further substitution of the ring with a variety of moieties enhanced potency (50–54). Three analogs (45, 48, and 54) were evaluated in our in vitro DMPK assays, and while the protein binding results were encouraging with more than 10% unbound in each case, predicted hepatic clearance remained high (>48 mL min−1 kg−1).

In addition to the simple tertiary amines highlighted above, we also prepared a number of analogs with heterocyclic amines (Table 4). Substituted morpholine analogs 55–58 were potent mGlu2 NAMs with the dimethyl substituted analogs 57 and 58 offering potency superior to monomethyl analogs 55 and 56. Particularly encouraging was analog 58, which was predicted to be a low–moderate clearance compound in rats and was approximately 30% unbound in rat plasma. On the other hand, thiomorpholine 59 exhibited high clearance in vitro, and thiomorpholine 1,1-dioxide 60 showed reduced potency. We also prepared several analogs with seven-membered rings (63–66). Though most of these medium ring-containing analogs were moderate to weak mGlu2 NAMs, 1,4-thiazepane 65 was quite potent. Unfortunately, 65 was highly cleared in vitro; however, oxidation of the sulfur atom was a likely metabolic soft-spot, as clearance with 1,4-thiazepane 1,1-dioxide 66 was substantially reduced.

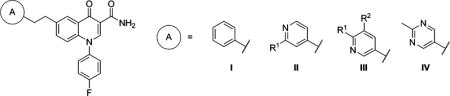

Turning our attention to the 6-aryloxymethyl ether analogs 70–78 uncovered several additional compounds with good mGlu2 NAM potency (Table 5). Several 3-pyridyl derivatives (70–74) were prepared, and 6-methyl derivative 72 and 6-chloro derivative 73 exhibited good potency. Interestingly, a trifluoromethyl group (74) did not function as an adequate alternative at this position. The pyridyl derivatives (75–77) demonstrated more modest differences in mGlu2 NAM activity, and in this case the trifluoromethyl (77) was only slightly less potent than its corresponding methyl comparator (76). Fraction unbound with these pyridyl analogs was in line with other similar analogs (see Table 1), and predicted clearance ranged from moderate (72 and 76) to high (73 and 75). Once again, we installed a 2-methylpyrimidin-5-yl ring (78) and observed positive results. Specifically, not only was 78 a potent mGlu2 NAM, it exhibited more than 10% fraction unbound in rat plasma and a low predicted clearance in rat liver microsomes.

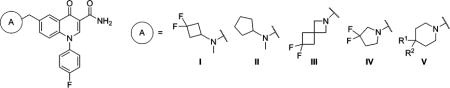

Finally, examination of 6-ethylene linked analogs 81–87 yielded a range of results (Table 6). Unsubstituted phenyl analog 81 demonstrated weak mGlu2 NAM activity; however, modification of the aromatic ring (A) to pyridine (82 and 84) improved potency approximately 15-fold. Unfortunately, both 82 and 84 were highly cleared in vitro. Substitution of 4-pyridyl analog 82 with a trifluoromethyl group (83) modestly enhanced potency but without reducing clearance. Substitution of 3-pyridyl analog 84 with trifluoromethyl (85) and fluorine (86) was unfavorable for mGlu2 NAM activity. Again the 2-methylpyrimidin-5-yl ring (87) proved an attractive moiety, having demonstrated the most potent activity and highest fraction unbound in this set of analogs. Also, although predicted hepatic clearance for 87 remained on the high end, it was improved relative to other analogs in this class (82–84).

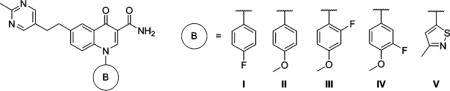

Having developed substantial SAR at the 6-position of the chemotype, we wanted to conduct limited exploration of another area as well. We chose ethylene linked analog 87 as a useful comparator given its overall profile. As such, additional analogs of 87 with alternative aromatic rings (B) to the 4-fluorophenyl ring were prepared and tested (Table 7). Replacement of the 4-fluoro group (87) with a 4-methoxy group (88) improved mGlu2 NAM potency slightly, but the predicted hepatic clearance of 88 remained high. Since methoxy groups increase electron density on the ring, fluorinated analogs 89 and 90 were prepared; however, these modifications failed to improve metabolic stability. It was encouraging to see that the 4-fluorophenyl ring could be replaced altogether with a 3-methylisothiazol-5-yl ring (91). Analog 91 demonstrated a 2-fold drop in potency relative to 87; yet, this modification was considered efficient by the LLE quotient, as it was a less lipophilic compound. Of note, 91 had an increased fraction unbound and a marginally and perhaps insignificantly lower predicted hepatic clearance than 87. Continued exploration of this region (B) of the scaffold is clearly worthwhile; however, at this point, we decided to more thoroughly profile some of the promising analogs discovered thus far to evaluate the full potential of the 4-oxo-1-aryl-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxamides as a lead series for the discovery of druglike mGlu2 NAMs.

Prior to discussing the results of extended profiling of select 4-oxo-1-aryl-1,4-dihydroquinolines, it is worth briefly discussing the results obtained with the 4H-quinolizin-4-one analogs (Table 8). Whether in the case of the ether analogs (99–102) or methylene amine analogs (106–108), mGlu2 NAM potency was consistently weak. In fact, when compared to their analogous compounds in the 4-oxo-1-aryl-1,4-dihydroquinoline series, these analogs were notably less potent in each case. These results are important because it illustrates that these two cores are not uniformly interchangeable. Moreover, it provides another example of the subtleties of SAR often seen in the design of allosteric modulators of class C GPCRs.52–54

Extended Characterization of Selected Analogs

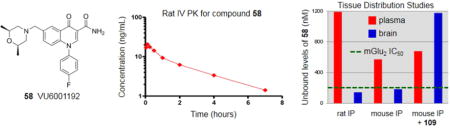

In choosing the initial compounds for more in depth evaluation, we sought molecules with both promising mGlu2 NAM potency and in vitro DMPK profiles while also desiring some structural diversity at the 6-position substituent. As such, we selected ether 17, amine 34, methylene amines 54 and 58, and ethylene linked analog 87 for further profiling (Table 9). Since the potential therapeutic applications for an mGlu2 NAM are in the area of CNS disorders, blood–brain barrier (BBB) penetration seemed a logical next step for evaluation in this new series. It should be noted that the fraction unbound in rat plasma ranged from 0.083 to 0.306 with these compounds; thus, consideration of unbound fraction alongside potency and CNS exposure is required to fully evaluate these compounds. Toward this end, we employed rat cassette pharmacokinetics (PK) tissue distribution studies using intravenous (iv) dosing and single time point analysis.55 Such an approach has repeatedly proven a rapid and cost-effective mechanism for preliminary assessment of BBB penetration. In addition to the already measured protein binding in rat plasma, the protein binding of these compounds in rat brain homogenates was also assessed. Unfortunately, the observed brain to plasma ratio (Kp) for each compound was low, ranging from 0.04 (34) to 0.36 (54). Calculation of the unbound brain to unbound plasma ratio (Kp,uu) gave values that were all below 0.25, indicating possible transporter effects.56 Thus, analogs 58 and 87 were selected for permeability studies in Madin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells transfected with the human MDR1 gene to assess potential P-glycoprotein (P-gp) mediated efflux.57 Both compounds demonstrated substantial efflux with ratios of 52 and 44, respectively. While it was disappointing to learn that this scaffold appeared to suffer from P-gp-mediated efflux, the absolute CNS concentrations observed with 58 and its other properties raised the possibility that it might still be a valuable tool.

Table 9.

Rat Intravenous Cassette and MDR1-MDCK Permeability Results

| ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | mGlu2 IC50 (nM) | rat plasma fua | rat brain fua | rat iv tissue distribution resultsb

|

permeability in MDR1-MDCK cells

|

|||||

| plasma concn (nM)c | brain concn (nM)c | Kpd | Kp,uue | A–B Papp (10−6 cm/s) | B–A Papp (10−6 cm/s) | efflux ratio | ||||

| 17 | 850 | 0.083 | 0.087 | 55.8 | 9.2 | 0.16 | 0.17 | |||

| 34 | 341 | 0.137 | 0.095 | 83.0 | 3.0 | 0.04 | 0.02 | |||

| 54 | 161 | 0.109 | 0.068 | 60.5 | 21.6 | 0.36 | 0.22 | |||

| 58 | 207 | 0.306 | 0.191 | 56.9 | 18.0 | 0.32 | 0.23 | 1.54 | 79.7 | 52 |

| 87 | 215 | 0.157 | 0.160 | 122 | 5.6 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 1.58 | 69.4 | 44 |

fu = fraction unbound.

n = 2; dose = 0.2 mg/kg per compound; solution in 8% EtOH, 30% PEG 400, 62% DMSO (2 mg/mL total).

15 min after dose.

Kp = total brain to total plasma ratio.

Kp,uu = unbound brain (brain fu × total brain) to unbound plasma (plasma fu × total plasma) ratio.

Further profiling of compound 58 (VU6001192) began with determination of its full selectivity versus other members of the mGlu family. Selectivity versus fellow group II receptor subtype, mGlu3, was particularly critical to assess. Gratifyingly, we evaluated the selectivity of 58 versus rat mGlu3 using 10-point concentration–response curve (CRC) analysis in the presence of an EC80 concentration of glutamate, and 58 was inactive up to the highest concentration tested (30 μM). For evaluation of selectivity versus other members of the mGlu family, the effect of 10 μM 58 on the orthosteric agonist CRC was measured in fold-shift experiments.58,59 Fortunately, no activity at the other mGlus was noted in these assays. Because the genesis for the 4-oxo-1-aryl-1,4-dihydroquinoline chemotype as a mGlu2 NAM scaffold was inspired in part by a known M1 PAM scaffold, we also evaluated 58 in our human M1 functional assay60 and observed no activity up to the highest concentration tested (30 μM). Ancillary pharmacology was evaluated through screening 58 at 10 μM in a commercially available radioligand binding assay panel of 68 clinically relevant GPCRs, ion channels, kinases, and transporters,61 and no significant responses were noted.62

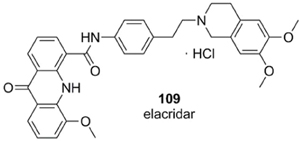

Having established the excellent selectivity profile of 58, we progressed the compound to additional and more definitive PK studies in both rats and mice (Table 10).63 In spite of its predicted low–moderate clearance, a time course study using iv dosing showed 58 to be a high clearance compound; however, the volume of distribution at steady state (VSS) was high and the half-life was approximately 2 h. Thus, intraperitoneal (ip) dosing was chosen as a route that was both convenient for future use in behavioral models and had the likelihood of providing superior exposure to oral dosing. An ip tissue distribution study in rats at 30 mg/kg gave Kp and Kp,uu values similar to those observed previously; yet, we observed a brain concentration of 760 nM, which translates to an unbound brain concentration of 145 nM and is very near the functional mGlu2 IC50 (207 nM). An analogous study in mice at the same dose gave similar results with a brain concentration of 716 nM, which translates to an unbound brain concentration of 184 nM. Finally, to verify the role of P-gp in vivo, we repeated the study in mice with the modification of pretreating the animals with the known P-gp inhibitor 109 (elacridar).64 The impact of this modification was profound, as the exposure of 58 in the brain was increased more than 6-fold without impacting the systemic exposure in plasma.

Table 10.

Intravenous PK and Tissue Distribution Studies with Compound 58

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Binding (fu)a | Rat IV PKb | Rat IP Tissue Distributionc,d | |||||||

| rat plasma | 0.306 | dose | 0.2 mg/kg | dose | 30 mg/kg | ||||

| rat brain homogenates | 0.191 | t1/2 | 141 minutes | plasma concentration | 3900 nM | ||||

| mouse plasma | 0.315 | CLplasma | 75.8 mL/min/kg | brain concentration | 760 nM | ||||

| mouse brain homogenates | 0.257 | Vss | 13.3 L/kg | Kpe | Kp,uuf | 0.20 | 0.12 | ||

|

| |||||||||

|

Mouse IP Tissue Distributionc,d | Mouse IP Tissue Distribution + 109c,d,g | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| dose | 30 mg/kg | dose | 30 mg/kg | ||||||

| plasma concentration | 1820 nm | plasma concentration | 2160 nm | ||||||

| brain concentration | 716 nm | brain concentration | 4580 nm | ||||||

| Kpe | Kp,uuf | 0.39 | 0.32 | Kpe | Kp,uuf | 2.1 | 1.7 | ||

fu = fraction unbound.

n = 2; solution in solution in 9% EtOH, 38% PEG 400, 53% DMSO (1 mg/mL).

n = 2; fine homogeneous suspension in 10% Tween-80 in H2O.

15 min after dose of 58.

Kp = total brain to total plasma ratio.

Kp,uu = unbound brain (brain fu × total brain) to unbound plasma (plasma fu × total plasma) ratio.

Compound 109 dosed 1 h prior to compound 58 at 20 mg/kg.

CONCLUSION

A potent and highly selective mGlu2 NAM tool compound 58 was discovered through scaffold hopping a series in the patent literature and recognizing the possibility that an established M1 PAM series might function as a viable chemotype for new analog design. Diverse functional groups were tolerated at the 6-position of the new chemotype, and limited work established the potential for further modifications at the 1-position. While the utility of the compounds tested thus far is hampered by P-gp mediated efflux that limits CNS exposure, the overall profile of 58 remains interesting. The compound exhibits an unbound fraction of 25–30% in rodent brain homogenates, and a dose of 30 mg/kg using ip dosing produces unbound brain concentrations near the functional mGlu2 IC50. Conceivably, higher doses could be employed in order to reach pharmacologically relevant concentrations in the CNS. Perhaps more attractive is the fact that pretreatment with a commercially available P-gp inhibitor boosts the unbound brain exposure of 58 to more than 5-fold the mGlu2 IC50 at the same dose. The study of 58 in behavioral models relevant to mGlu2 inhibition is planned and will be the subject of future communications.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

The synthesis of compound 58 and its associated intermediates is described below for convenience. Synthetic details for other compounds can be found in the Supporting Information.

Ethyl 3-(5-Bromo-2-fluorophenyl)-3-oxopropanoate (14)

3-Ethoxy-3-oxopropanoic acid 13 (2.16 mL, 18.3 mmol, 2.00 equiv) was dissolved in THF (91 mL) in an oven-dried round-bottom flask, and 2,2′-bipyridyl (8.00 mg, 0.0512 mmol, 0.0056 equiv) was added as an indicator. The reaction was cooled to −30 °C, and n-butyllithium (1.6 M in hexanes) (29.0 mL, 45.6 mmol, 4.00 equiv) was added dropwise over 20 min. Upon final addition the reaction turned red at which point it was allowed to warm to −5 °C. The reaction was allowed to stir at −5 °C for 15 min, during which time the red color began to dissipate. Enough n-butyllithium was added to allow the red color to persist. The reaction was then cooled to −78 °C, and 5-bromo-2-fluorobenzoyl chloride (2.17 g, 9.14 mmol, 1.00 equiv) was added dropwise as a solution in THF (6.9 mL). The reaction was allowed to stir at −78 °C for 30 min and then allowed to warm to −30 °C and stirred for an additional 30 min. The reaction was poured onto ice-cold 1 N HCl (92 mL), and the mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate (1×) and DCM (2×). The combined organics were dried (MgSO4), filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. Purification by flash chromatography on silica gel afforded 1.78 g (67%) of the title compound as an off-white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 7.97 (dd, J = 6.5, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.91–7.86 (m, 1H), 7.40–7.34 (m, 1H), 4.13–4.07 (m, 4H), 1.15 ppm (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 189.68 (d, J(C,F) = 3.2 Hz), 167.09, 160.26 (d, J(C,F) = 255 Hz), 138.09 (d, J(C,F) = 9.5 Hz), 132.49 (d, J(C,F) = 2.2 Hz), 126.16 (d, J(C,F) = 13.3 Hz), 119.51 (d, J(C,F) = 25.1 Hz), 116.64, 60.71, 48.81, 13.92 ppm. HRMS (ESI): calculated for C11H10BrFO3 [M], 287.9797; found, 287.9794. LCMS tR = 0.989 min, ES-MS m/z = 289.0 [M + H]+.

Ethyl 6-Bromo-1-(4-fluorophenyl)-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylate (15, Where Ar = 4-Fluorophenyl)

Compound 14 (2.87 g, 9.93 mmol, 1.00 equiv) and N,N-dimethylformamide dimethyl acetal (1.87 mL, 14.9 mmol, 1.50 equiv) were dissolved in DMF (33 mL) in a microwave vial and heated in a microwave reactor at 120 °C for 15 min. To this mixture was then added 4-fluoroaniline (1.41 mL, 14.9 mmol, 1.50 equiv), and the reaction was heated in a microwave reactor at 150 °C for 20 min. The reaction mixture was diluted with ethyl acetate and washed with water (2×). The aqueous layers were back-extracted with ethyl acetate, and the combined organics were dried (MgSO4), filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. Purification by flash chromatography on silica gel afforded 3.79 g (98%) of the title compound as yellow solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 8.47 (s, 1H), 8.31 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.81 (dd, J = 9.1, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.77–7.73 (m, 2H), 7.54–7.50 (m, 2H), 6.92 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 4.20 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 1.25 ppm (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 171.80, 163.90, 162.43 (d, J(C,F) = 247.5 Hz), 149.02, 139.70, 136.38 (d, J(C,F) = 2.8 Hz), 135.37, 130.17 (d, J(C,F) = 9.0 Hz), 128.83, 128.15, 120.73, 118.06, 117.26 (d, J(C,F) = 23.2 Hz), 110.88, 60.04, 14.21 ppm. HRMS (ESI): calculated for C18H13BrFNO3 [M], 389.0063; found, 389.0062. LCMS tR = 0.934 min, ES-MS m/z = 390.2 [M + H]+.

6-Bromo-1-(4-fluorophenyl)-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxamide (16, Where Ar = 4-Fluorophenyl)

Ethyl 6-bromo-1-(4-fluorophenyl)-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylate (1.00 g, 2.56 mmol, 1.00 equiv) was suspended in 7 N ammonia in methanol (30 mL) in a microwave vial, and the reaction was heated in a microwave reactor at 150 °C for 60 min. The reaction was concentrated to afford 881 mg (95%) of the title compound as a brown solid that was used without further purification. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 9.08 (d, J = 4.0 Hz, 1H), 8.57 (s, 1H), 8.43 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.85 (dd, J = 9.1, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.77–7.73 (m, 2H), 7.66 (d, J = 4.1 Hz, 1H), 7.56–7.50 (m, 2H), 7.02 ppm (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 174.64, 164.83, 162.46 (d, J(C,F) = 247.6 Hz), 148.42, 139.85, 136.50 (d, J(C,F) = 2.8 Hz), 135.66, 129.97 (d, J(C,F) = 9.3 Hz), 128.09, 128.07, 120.86, 118.19, 117.31 (d, J(C,F) = 23.3 Hz), 112.07 ppm. HRMS (ESI): calculated for C16H10BrFN2O2 [M], 359.9910; found, 359.9909. LCMS tR = 0.929 min, ES-MS m/z = 361.2 [M + H]+.

1-(4-Fluorophenyl)-4-oxo-6-vinyl-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxamide (43, Where Ar = 4-Fluorophenyl)

To a solution of 6-bromo-1-(4-fluorophenyl)-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxamide (450 mg, 1.25 mmol, 1.0 equiv), triethylamine (174 μL, 1.25 mmol, 1.0 equiv), and Pd(dppf)Cl2·CH2Cl2 (18.2 mg, 0.025 mmol, 0.2 equiv) in 1-propanol (8.3 mL) was added potassium vinyltrifluoroborate (200 mg, 1.5 mmol, 1.2 equiv). The mixture was purged with argon and stirred at 100 °C for 16 h. The reaction was filtered through Celite and washed very well with a 5% MeOH in DCM solution. The filtrate was concentrated in vacuo to give 385 mg (100%) of the title compound, which was used without further purification. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 9.23 (d, J = 4.2 Hz, 1H), 8.55 (s, 1H), 8.36 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.89 (dd, J = 1.8, 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.79–7.75 (m, 2H), 7.64 (d, J = 4.2 Hz, 1H), 7.54 (t, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.03 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 6.93 (q, J = 11, 6.6 Hz, 1H), 5.95 (d, J = 17.6 Hz, 1H), 5.39 ppm (d, J = 11 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 175.79, 165.17, 162.36 (d, J(C,F) = 247.0 Hz), 147.77, 140.24, 136.74 (d, J(C,F) = 3.2 Hz), 135.38, 134.17, 130.1, 129.93 (d, J(C,F) = 9.0 Hz), 126.74, 123.72, 118.65, 117.35 (d, J(C,F) = 23.4 Hz), 115.9, 111.72 ppm. HRMS (ESI): calculated for C18H13FN2O2 [M], 308.0961; found, 308.0964. LCMS tR = 0.922 min, ES-MS m/z = 309.2 [M + H]+.

1-(4-Fluorophenyl)-6-formyl-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxamide (44, Where Ar = 4-Fluorophenyl)

To a solution of 1-(4-fluorophenyl)-4-oxo-6-vinyl-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxamide (385 mg, 1.25 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in 3:1 acetone/water (8 mL) was added N-oxide-4-methylmorpholine (220 mg, 1.87 mmol, 1.5 equiv) and osmium tetroxide (6.3 mg, 0.025 mmol, 0.02 equiv). After the reaction was stirred for 1 h, sodium periodate (294 mg, 1.37 mmol, 1.1 equiv) was added. After another 2 h, the reaction was diluted with EtOAc and washed well with a 10% NaS2O3 solution. The organic layer was dried (MgSO4), filtered, and concentrated in vacuo to give 365 mg (94%) of the title compound that was used without further purification. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 10.17 (s, 1H), 9.10 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 8.93 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 8.62 (s, 1H), 8.12 (dd, J = 1.8, 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.82–7.78 (m, 2H), 7.74 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 7.56 (t, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.22 ppm (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 192.23, 175.88, 164.68, 162.49 (d, J(C,F) = 247 Hz), 149.06, 144.23, 136.61 (d, J(C,F) = 3.2 Hz), 132.48, 130.98, 130.41, 130.0 (d, J(C,F) = 9.3 Hz), 126.54, 119.46, 117.37 (d, J(C,F) = 23.3 Hz), 112.78 ppm. HRMS (ESI) calculated for C17H11FN2O3 [M], 310.0754; found, 310.0757. LCMS tR = 0.732 min, ES-MS m/z = 311.2 [M + H]+.

6-((cis-2,6-Dimethylmorpholino)methyl)-1-(4-fluorophenyl)-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxamide (58)

A solution of 1-(4-fluorophenyl)-6-formyl-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxamide (580 mg, 1.87 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in dichloromethane (1 mL), cis-2,6-dimethylmorpholine (461 μL, 3.74 mmol, 2.0 equiv), and acetic acid (268 μL, 4.67 mmol, 2.5 equiv) was stirred for 1 h. Sodium triacetoxyborohydride (594 mg, 2.80 mmol, 1.5 equiv) was added. After 16 h, the reaction was concentrated to dryness. Purification by reverse phase HPLC afforded 620 mg (81%) of the title compound as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.23 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 1H), 8.55 (s, 1H), 8.26 (d, J = 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.77–7.73 (m, 2H), 7.65 (dd, J = 1.8, 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (t, J = 8.7, 2H), 7.03 (d, J = 8.7, 1H), 3.57–3.52 (m, 4H), 2.65 (d, J = 10.7 Hz, 2H), 1.68 (t, J = 10.7 Hz, 2H), 1.01 ppm (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 175.8, 165.26, 162.36 (d, J(C,F) = 247 Hz), 147.78, 139.9, 136.82 (d, J(C,F) = 3.1 Hz), 135.26, 133.91, 129.98 (d, J(C,F) = 8.9 Hz), 126.41, 125.85, 118.26, 117.22 (d, J(C,F) = 23.0 Hz), 111.59, 70.97, 61.23, 58.81, 18.96 ppm. HRMS (ESI) calculated for C23H24FN3O3 [M], 409.1802; found, 409.1804. LCMS tR = 0.644 min, ES-MS m/z = 410.3 [M + H]+.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the generous support of the National Institute of Mental Health for the funding of this work, NIMH Grant R01MH099269 (K.A.E.) and Grant U54MH084659 (C.W.L.).

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- 7TM

seven transmembrane

- Ac

acetate

- BBB

blood−brain barrier

- Bu

butyl

- CL

clearance

- CNS

central nervous system

- CRC

concentration−response curve

- dba

dibenzylideneacetone

- DCE

1,2-dichloroethane

- DIEA

N,N-diisopropylethylamine

- DME

1,2-dimethoxyethane

- DMF

N,N-dimethylformamide

- DMPK

drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

- dppf

1,1′-bis(diphenylphosphino)-ferrocene

- DtBAD

di-tert-butyl azodicarboxylate

- Et

ethyl

- Fu

fraction unbound

- GPCR

G-protein-coupled receptor

- ip

intraperitoneal

- iv

intravenous

- Kp

brain to plasma ratio

- Kp,uu

unbound brain to unbound plasma ratio

- LLE

ligand-lipophilicity efficiency

- M1

muscarinic acetylcholine receptor subtype 1

- max

maximum

- MDCK

Madin-Darby canine kidney

- MDD

major depressive disorder

- Me

methyl

- mGlu

metabotropic glutamate receptor

- NAM

negative allosteric modulator

- NBS

N-bromosuccinimide

- NMO

N-methylmorpholine N-oxide

- OCD

obsessive-compulsive disorder

- PAM

positive allosteric modulator

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- Ph

phenyl

- P-gp

P-glycoprotein

- PK

pharmacokinetics

- pTSA

p-toluenesulfonic acid

- RLM

rat liver microsome

- SAR

structure-activity relationship

- t-BuXphos

2-di-tert-butylphosphino-2′,4′,6′-triisopropylbiphenyl

- TBAF

tetrabutylammonium fluoride

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

- TRD

treatment-resistant depression

- T

time

- t1/2

half-life

- VSS

volume of distribution at steady-state

- Xantphos

4,5-bis(diphenylphosphino)-9,9-dimethylxanthene

Footnotes

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01371.

Experimental procedures and spectroscopic data for additional compounds, detailed molecular pharmacology, DMPK, behavioral methods, ancillary pharmacology profile for compound 58, and 1H and 13C spectra for compound 58 and its associated intermediates (PDF) Molecular formula strings (CSV)

Author Contributions

Drs. K. A. Emmitte and C. W. Lindsley directed and designed the chemistry. Dr. A. S. Felts, K. A. Smith, and Dr. J. L. Engers performed the medicinal chemistry. Drs. P. J. Conn and C. M. Niswender directed and designed the molecular pharmacology experiments. Dr. A. L. Rodriguez directed and performed molecular pharmacology experiments. D. F. Venable performed molecular pharmacology experiments. Dr. J. S. Daniels directed and designed the DMPK experiments. Drs. C. W. Locuson and A. L. Blobaum directed DMPK experiments and performed bioanalytical work. R. D. Morrison performed bioanalytical work. S. Chang performed in vitro DMPK work. F. W. Byers performed in vivo DMPK work.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Niswender CM, Conn PJ. Metabotropic glutamate receptors: Physiology, pharmacology, and disease. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;50:295–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.011008.145533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schoepp DD, Jane DE, Monn JA. Pharmacological agents acting at subtypes of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:1431–1476. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conn PJ, Pin J-P. Pharmacology and functions of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1997;37:205–237. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaki S, Ago Y, Palucha-Paniewiera A, Matrisciano F, Pilc A. mGlu2/3 and mGlu5 receptors: Potential targets for novel antidepressants. Neuropharmacology. 2013;66:40–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palucha A, Pilc A. Metabotropic glutamate receptor ligands as possible anxiolytic and antidepressant drugs. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;115:116–147. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellaithy A, Younkin J, Gonzalez-Maeso J, Logothetis DE. Positive allosteric modulators of metabotropic glutamate 2 receptors in schizophrenia treatment. Trends Neurosci. 2015;38:506–516. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Celanire S, Sebhat I, Wichmann J, Mayer S, Schann S, Gatti S. Novel metabotropic glutamate receptor 2/3 antagonists and their therapeutic applications: a patent review (2005–present) Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2015;25:69–90. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2014.983899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ornstein PL, Bleisch TJ, Arnold MB, Kennedy JH, Wright RA, Johnson BG, Tizzano JP, Helton DR, Kallman MJ, Schoepp DD. 2-Substituted (2SR)-2-amino-2-((1SR,2SR)-2-carboxycycloprop-1-yl)glycines as potent and selective antagonists of group II metabotropic glutamate receptors. 2. Effects of aromatic substitution, pharmacological characterization, and bioavailability. J Med Chem. 1998;41:358–378. doi: 10.1021/jm970498o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaki S, Yoshikawa R, Hirota S, Shimazaki T, Maeda M, Kawashima N, Yoshimizu T, Yasuhara A, Sakagami K, Okuyama S, Nakanishi S, Nakazato A. MGS0039: a potent and selective group II metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonist with antidepressant-like activity. Neuropharmacology. 2004;46:457–467. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bespalov AY, van Gaalen MM, Sukhotina IA, Wicke K, Mezler M, Schoemaker H, Gross G. Behavioral characterization of the mGlu group II/III receptor antagonist, LY-341495, in animal models of anxiety and depression. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;592:96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.06.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimazaki T, Iijima M, Chaki S. Anxiolytic-like activity of MGS0039, a potent group II metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonist, in a marble-burying behavior test. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;501:121–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshimizu T, Shimazaki T, Ito A, Chaki S. An mGluR2/3 antagonist, MGS0039, exerts antidepressant and anxiolytic effects in behavioral models in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2006;186:587–593. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0390-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins GA, Ballard TM, Kew JN, Richards JG, Kemp JA, Adam G, Woltering T, Nakanishi S, Mutel V. Pharmacological manipulation of mGlu2 receptors influences cognitive performance in the rodent. Neuropharmacology. 2004;46:907–917. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim SH, Steele JW, Lee SW, Clemenson GD, Carter TA, Treuner K, Gadient R, Wedel P, Glabe C, Barlow C, Ehrlich ME, Gage FH, Gandy S. Proneurogenic group II mGluR antagonist improves learning and reduces anxiety in Alzheimer Aβ oligomer mouse. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:1235–1242. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim SH, Fraser PE, Westaway D, St George-Hyslop PH, Ehrlich ME, Gandy S. Group II metabotropic glutamate receptor stimulation triggers production and release of Alzheimer’s amyloid β42 from isolated intact nerve terminals. J Neurosci. 2010;30:3870–3875. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4717-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshimizu T, Chaki S. Increased cell proliferation in the adult mouse hippocampus following chronic administration of group II metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonist, MGS0039. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;315:493–496. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.01.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gleason SD, Li X, Smith IA, Ephlin JD, Wang XS, Heinz BA, Carter JH, Baez M, Yu J, Bender DM, Witkin JM. mGlu2/3 agonist-induced hyperthermia: An in vivo assay for detection of mGlu2/3 receptor antagonism and its relation to antidepressant-like efficacy in mice. CNS Neurol Disord: Drug Targets. 2013;12:554–566. doi: 10.2174/18715273113129990079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koike H, Fukumoto K, Iijima M, Chaki S. Role of BDNF/TrkB signaling in antidepressant-like effects of a group II metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonist in animal models of depression. Behav Brain Res. 2013;238:48–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koike H, Iijima M, Chaki S. Involvement of the mammalian target of rapamycin signaling in the antidepressant-like effect of group II metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonists. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61:1419–1423. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karasawa J, Shimazaki T, Kawashima N, Chaki S. AMPA receptor stimulation mediates the antidepressant-like effect of a group II metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonist. Brain Res. 2005;1042:92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iijima M, Koike H, Chaki S. Effect of an mGlu2/3 receptor antagonist on depressive behavior induced by withdrawal from chronic treatment with methamphetamine. Behav Brain Res. 2013;246:24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Markou A. Metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonists: Novel therapeutics for nicotine dependence and depression? Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ago Y, Yano K, Araki R, Hiramatsu N, Kita Y, Kawasaki T, Onoe H, Chaki S, Nakazato A, Hashimoto H, Baba A, Takuma K, Matsuda T. Metabotropic glutamate 2/3 receptor antagonists improve behavioral and prefrontal dopaminergic alterations in the chronic corticosterone-induced depression model in mice. Neuropharmacology. 2013;65:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dwyer JM, Lepack AE, Duman RS. mGluR2/3 blockade produces rapid and long-lasting reversal of anhedonia caused by chronic stress exposure. J Mol Psychiatry. 2013;1:15. doi: 10.1186/2049-9256-1-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Campo B, Kalinichev M, Lambeng N, Yacoubi ME, Royer-Urios I, Schneider M, Legrand C, Parron D, Girard F, Bessif A, Poli S, Vaugeois J-M, Le Poul E, Célanire S. Characterization of an mGluR2/3 negative allosteric modulator in rodent models of depression. J Neurogenet. 2011;25:152–166. doi: 10.3109/01677063.2011.627485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pritchett D, Jagannath A, Brown LA, Tam SKE, Hasan S, Gatti S, Harrison PJ, Bannerman DM, Foster RG, Peirson SN. Deletion of metabotropic glutamate receptors 2 and 3 (mGlu2 & mGlu3) in mice disrupts sleep and wheel-running activity, and increases the sensitivity of the circadian system to light. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0125523. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woltering TJ, Wichmann J, Goetschi E, Knoflach F, Ballard TM, Huwyler J, Gatti S. Synthesis and characterization of 1,3-dihydro-benzo[b][1,4]diazepin-2-one derivatives: Part 4. In vivo active potent and selective non-competitive metabotropic glutamate receptor 2/3 antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:6969–6974. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.09.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yacoubi ME, Vaugeois JM, Kalinichev M, Célanire S, Parron D, Le Poul E, Campo B. Effects of a mGluR2/3 negative allosteric modulator and a reference mGluR2/3 orthosteric antagonist in a genetic mouse model of depression. Behavioral Studies of Mood Disorders; Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience; San Diego, CA. Nov 13-17, 2010; Washington, DC: Society for Neuroscience; 2010. 886.14/VV7. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goeldner C, Ballard TM, Knoflach F, Wichmann J, Gatti S, Umbricht D. Cognitive impairment in major depression and the mGlu2 receptor as a therapeutic target. Neuropharmacology. 2013;64:337–346. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalinichev M, Campo B, Lambeng N, Célanire S, Schneider M, Bessif A, Royer-Urios I, Parron D, Legrand C, Mahious N, Girard F, Le Poul E. An mGluR2/3 negative allosteric modulator improves recognition memory assessed by natural forgetting in the novel object recognition test in rats. Memory Consolidation and Reconsolidation: Molecular Mechanisms II; Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience; San Diego, CA. Nov 13–17, 2010; Washington, DC: Society for Neuroscience; 2010. 406.9/MMM57. [Google Scholar]

- 31.WHO Drug Information. 3. Vol. 27. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2013. Structure of decoglurantis disclosed in Recommended International Nonproprietary Names (INN) p. 150. [Google Scholar]

- 32.ClinicalTrials.gov. ARTDeCo study: A study of RO4995819 in patients with major depressive disorder and inadequate response to ongoing antidepressant treatment. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01457677 (accessed August 12, 2015)

- 33.Sheffler DJ, Wenthur CJ, Bruner JA, Carrington SJS, Vinson PN, Gogi KK, Blobaum AL, Morrison RD, Vamos M, Cosford NDP, Stauffer SR, Daniels JS, Niswender CM, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. Development of a novel, CNS-penetrant, metabotropic glutamate receptor 3 (mGlu3) NAM probe (ML289) derived from a closely related mGlu5 PAM. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:3921–3925. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.04.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wenthur CJ, Morrison R, Felts AS, Smith KA, Engers JL, Byers FW, Daniels JS, Emmitte KA, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. Discovery of (R)-(2-fluoro-4-((-4-methoxyphenyl)ethynyl)phenyl-(3-hydroxypiperidin-1-yl)methanone (ML337), An mGlu3 selective and CNS penetrant negative allosteric modulator (NAM) J Med Chem. 2013;56:5208–5212. doi: 10.1021/jm400439t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walker AG, Wenthur CJ, Xiang Z, Rook JM, Emmitte KA, Niswender CM, Lindsley CW, Conn PJ. Metabotropic glutamate receptor 3 activation is required for long-term depression in medial prefrontal cortex and fear extinction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:1196–1201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416196112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Engers JL, Rodriguez AL, Konkol LC, Morrison RD, Thompson AD, Byers FW, Blobaum AL, Chang S, Venable DF, Loch MT, Niswender CM, Daniels JS, Jones CK, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW, Emmitte KA. Discovery of a selective and CNS penetrant negative allosteric modulator of metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 3 with antidepressant and anxiolytic activity in rodents. J Med Chem. 2015;58:7485–7500. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bungard CJ, Converso A, De Leon P, Hanney B, Hartingh TJ, Manikowski JJ, Manley PJ, Meissner R, Meng Z, Perkins JJ, Rudd MT, Shu Y. Quinoline carboxamide and quinoline carbonitrile derivatives as mGluR2-negative allosteric modulators, compositions, and their use. WO 2013/066736 A1. PCT Int Pat Appl. 2013 May 10;

- 38.Kuduk SD, Di Marco CN, Cofre V, Ray WJ, Ma L, Wittmann M, Seager MA, Koeplinger KA, Thompson CD, Hartman GD, Bilodeau MT. Fused heterocyclic M1 positive allosteric modulators. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:2769–2772. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuduk SD, Di Marco CN, Chang RK, Ray WJ, Ma L, Wittmann M, Seager MA, Koeplinger KA, Thompson CD, Hartman GD, Bilodeau MT. Heterocyclic fused pyridone carboxylic acid M1 positive allosteric modulators. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:2533–2537. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.02.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang FV, Shipe WD, Bunda JL, Nolt MB, Wisnoski DD, Zhao Z, Barrow JC, Ray WJ, Ma L, Wittman M, Seager MA, Koeplinger KA, Hartman GD, Lindsley CW. Parallel synthesis of N-biaryl quinolone carboxylic acids as selective M1 positive allosteric modulators. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:531–536. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.11.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anderson KW, Ikawa T, Tundel RE, Buchwald SL. The selective reaction of aryl halides with KOH: Synthesis of phenols, aromatic ethers, and benzofurans. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:10694–10695. doi: 10.1021/ja0639719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.But TYS, Toy PH. The Mitsunobu reaction: Origin, mechanism, improvements, and applications. Chem-Asian J. 2007;2:1340–1355. doi: 10.1002/asia.200700182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Surry DS, Buchwald SL. Biaryl phosphane ligands in palladium-catalyzed amination. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:6338–6361. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Molander GA, Rodríguez Rivero M. Suzuki cross-coupling reactions of potassium alkenyltrifluoroborates. Org Lett. 2002;4:107–109. doi: 10.1021/ol0169729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thorand S, Krause N. Improved procedures for the palladium-catalyzed coupling of terminal alkynes with aryl bromides (Sonogashira coupling) J Org Chem. 1998;63:8551–8553. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kuduk SD, Chang RK, Di Marco CN, Pitts DR, Greshock TJ, Ma L, Wittmann M, Seager MA, Koeplinger KA, Thompson CD, Hartman GD, Bilodeau MT, Ray WJ. Discovery of a selective allosteric M1 receptor modulator with suitable development properties based on a quinolizidinone carboxylic acid scaffold. J Med Chem. 2011;54:4773–4780. doi: 10.1021/jm200400m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuduk SD, Chang RK, Di Marco CN, Ray WJ, Ma L, Wittmann M, Seager MA, Koeplinger KA, Thompson CD, Hartman GD, Bilodeau MT. Quinolizidinone carboxylic acid selective M1 allosteric modulators: SAR in the piperidine series. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:1710–1715. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.01.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuduk SD, Chang RK, Di Marco CN, Ray WJ, Ma L, Wittmann M, Seager MA, Koeplinger KA, Thompson CD, Hartman GD, Bilodeau MT. Quinolizidinone carboxylic acids as CNS penetrant, selective M1 allosteric muscarinic receptor modulators. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2010;1:263–267. doi: 10.1021/ml100095k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Obach RS. Prediction of human clearance of twenty-nine drugs from hepatic microsomal intrinsic clearance data: An examination of in vitro half-life approach and nonspecific binding to microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos. 1999;27:1350–1359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kalvass JC, Maurer TS. Influence of nonspecific brain and plasma binding on CNS exposure: implications for rational drug discovery. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2002;23:327–338. doi: 10.1002/bdd.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leeson PD, Springthorpe B. The influence of drug-like concepts on decision-making in medicinal chemistry. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2007;6:881–890. doi: 10.1038/nrd2445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stauffer SL. Progress toward positive allosteric modulators of the metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5 (mGlu5) ACS Chem Neurosci. 2011;2:450–470. doi: 10.1021/cn2000519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Robichaud AJ, Engers DW, Lindsley CW, Hopkins CR. Recent progress on the identification of metabotropic glutamate 4 receptor ligands and their potential utility as CNS therapeutics. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2011;2:433–449. doi: 10.1021/cn200043e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Emmitte KA. Recent advances in the design and development of novel negative allosteric modulators of mGlu5. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2011;2:411–432. doi: 10.1021/cn2000266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bridges TM, Morrison RD, Byers FW, Luo S, Daniels JS. Use of a novel rapid and resource-efficient cassette dosing approach to determine the pharmacokinetics and CNS distribution of small molecule 7-transmembrane receptor allosteric modulators in rat. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2014;2:e00077. doi: 10.1002/prp2.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Di L, Rong H, Feng B. Demystifying brain penetration in central nervous system drug discovery. J Med Chem. 2013;56:2–12. doi: 10.1021/jm301297f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang Q, Rager JD, Weinstein K, Kardos PS, Dobson GL, Li J, Hidalgo IJ. Evaluation of the MDR-MDCK cell line as a permeability screen for the blood−brain barrier. Int J Pharm. 2005;288:349–359. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Noetzel MJ, Rook JM, Vinson PN, Cho H, Days E, Zhou Y, Rodriguez AL, Lavreysen H, Stauffer SR, Niswender CM, Xiang Z, Daniels JS, Lindsley CW, Weaver CD, Conn PJ. Functional impact of allosteric agonist activity of selective positive allosteric modulators of metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5 in regulating central nervous system function. Mol Pharmacol. 2012;81:120–133. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.075184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Niswender CM, Johnson KA, Luo Q, Ayala JE, Kim C, Conn PJ, Weaver CD. A novel assay of Gi/o-linked G protein-coupled receptor coupling to potassium channels provides new insights into the pharmacology of the group III metabotropic glutamate receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:1213–1224. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.041053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tarr JC, Turlington ML, Reid PR, Utley TJ, Sheffler DJ, Cho HP, Klar R, Pancani T, Klein MT, Bridges TM, Morrison RD, Blobaum AL, Xiang Z, Daniels JS, Niswender CM, Conn PJ, Wood MR, Lindsley CW. Targeting selective activation of M1 for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: Further chemical optimization and pharmacological characterization of the M1 positive allosteric modulator ML169. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2012;3:884–895. doi: 10.1021/cn300068s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.LeadProfilingScreen (catalog 68), Eurofins Panlabs, Inc. (www.eurofinspanlabs.com).

- 62.Significant responses are defined as those that inhibited more than 50% of radioligand binding.

- 63.Bridges TM, Rook JM, Noetzel MJ, Morrison RD, Zhou Y, Gogliotti RD, Vinson PN, Xiang Z, Jones CK, Niswender CM, Lindsley CW, Stauffer SL, Conn PJ, Daniels JS. Biotransformation of a novel positive allosteric modulator of metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5 contributes to seizure-like adverse events in rats involving a receptor agonism-dependent mechanism. Drug Metab Dispos. 2013;41:1703–1714. doi: 10.1124/dmd.113.052084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kallem R, Kulkarni CP, Patel D, Thakur M, Sinz M, Singh SP, Mahammad SS, Mandlekar SA. simplified protocol employing elacridar in rodents: A screening model in drug discovery to assess P-gp mediated efflux at the blood brain barrier. Drug Metab Lett. 2012;6:134–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.