Abstract

BACKGROUND:

According to the existing literature on infertility, stress appears to be inevitably associated with infertility diagnosis and treatment in sub-fertile individuals. The epidemiological data on the prevalence and predictors of infertility-specific stress in cultural specific scenario are scarce. The objective of the present study was to estimate the prevalence of infertility-specific stress and identify predictors of infertility-specific stress in women diagnosed with primary infertility.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

This cross-sectional study was conducted on 300 infertile married women, diagnosed with primary infertility. The tools used for the assessment were “semi-structured questionnaire” compiled by the authors, “ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders (Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines),” and “Psychological Evaluation Test for infertility.”

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS:

Data were analyzed using SPSS (version 15). Chi-square test was used for univariate analysis followed by multiple logistic regressions between stress and the predictor variables.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION:

The prevalence of stress among women was 80%. Univariate analysis revealed that predictors of stress were years of marital life, duration of infertility, infertility type, history of gynecological surgery, cycles of ovulation induction with timed intercourse and intra-uterine inseminations, present and past psychiatric morbidity, coping difficulties, gynecological diagnosis, and severity of premenstrual dysphoria. Multivariate analysis showed leading associations of stress with infertility type and coping difficulties.

Keywords: Infertility-specific stress, predictors, prevalence, primary infertility, women

INTRODUCTION

Oxford dictionary defines the word stress as “a state of affair involving demand on physical or mental energy.” Stress can be physical and psychological. Mental health professionals refer to stress as “a dynamic condition in which an individual is confronted with an opportunity, constraint, or demand related to what he or she desires and for which the outcome is perceived to be both uncertain and important.”[1] Psychological stress is often seen to be a natural outcome of infertility, presenting in the form of an acute or chronic stressor in the affected persons. Diagnosis of infertility, recurrent implantation failures, and treatment failures serve as critical incidents that are sudden, unexpected, intimidating and may overwhelm an individual's capacity to respond adaptively. Such life events are often associated with an experience of psychological crisis. Infertile women routinely express their concerns of numerous constraints, demands, and losses that prevent these individuals from fulfilling their wish for child. Studies have found that couples described infertility as the most upsetting experience of their lives, classifying it as either stressful or extremely stressful.[2,3] Furthermore, feelings of psychological strain, helplessness, dwindling hopes, and a sense of loss of control are elevated in those who undergo assisted reproductive treatments than those who are trying to conceive spontaneously.[4] Moreover, literature also supports that stress may actually induce a biochemical milieu in women that is not conducive to conception.[5,6] In this situation, researchers, over the past two decades have exclusively begun to investigate factors predictive of infertility stress and other mental health outcomes in women undergoing infertility treatments.

Studies have demonstrated that infertility-specific stress is related to the age at diagnosis, duration of infertility, cause of infertility, repeated pregnancy tests, treatment failures, psychiatric morbidity, coping abilities, social support, stigma, and psychological interventions received.[7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17] In addition, reviews support the association between stress and psychiatric morbidity. The longing to achieve pregnancy and being unable to do so is what leaves women vulnerable to the onset of psychiatric morbidity.[18] Furthermore, studies propose that anxiety and depression would emerge after 4–6 years of infertility.[19] Also, peak of psychological morbidity could be seen during the 3rd year of infertility and after 6 years there may be a reduction in psychological symptoms in women.[20] Cross-sectional studies in India have revealed that infertile women experience poor subjective well-being, high level of psychological distress, sociocultural stressors, and significant coping difficulties.[21,22] In addition, 23% of infertile of them experienced comorbid anxiety disorders[3] and 6.4% fulfilled the criteria of reproductive mood disorders.[23]

Reviews have also emphasized that stress in females is particularly related to gender-specific diagnosis. Psychological response in women to female factor infertility is usually in the form of grief, suicidal ideation, self-blame, greater isolation, feelings of lack of support, anger, guilt, denial, anxiety, psychosomatic complains, and poor body image. Indian studies have also highlighted the issue of accentuated gender-based discrimination and social stigma that exacerbate distress in sub-fertile women.[24,25]

With this background, the aim of the present study was to conduct a clinic-based study to estimate the prevalence of infertility-specific stress and also to identify the predictors of infertility-specific stress in women diagnosed with primary infertility.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study participants

The sample of this cross-sectional study comprises of 300 married infertile women referred for psychological evaluation by the infertility experts. The inclusion criteria of the study were cases diagnosed with primary infertility and consenting to participate. The study excluded those women who were diagnosed with secondary infertility. The duration of the study was 6 months.

Data collection

Patients satisfying the study criteria were explained the purpose of study, its implications, and informed consent was taken for participation. Complete confidentiality was assured to them. The consenting women were interviewed for the assessment on relevant sociodemographic variables, clinical variables, and psychological variables, using a semi-structured questionnaire. Thereon, they were assessed for the presence of past or recent history of psychiatric morbidity using ICD-10-clinical descriptive and diagnostic guidelines.[26] Subsequently, participants were assessed for the presence of infertility-specific stress, using the “Psychological Evaluation Test for infertility.”[27] This was a clinician rated scale. The participants were instructed to complete the scale to the best of their knowledge. The participants were offered a free session of supportive psychotherapy postassessments. If any participant experienced significant psychiatric morbidity, they were psycho-educated and referred to the Department of Psychiatry for further management. This study was a part of larger research project and the ethical clearance from the concerned authorities was taken before the conduct of this work.

Sample size and statistical analysis

Anticipating the prevalence of stress in infertile females as 60%, the minimum number of subjects required for this study was observed to be 256 for a relative precision of 10% and 95% confidence level. All known female cases of primary infertility were invited to become a part of this study.

Data were analyzed using SPSS (SPSS for windows, version 15, September 2007, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The results were reported in medians, percentages, odds ratio, and 95% confidence interval (CI). Chi-square test was used for univariate analysis followed by multiple logistic regression with enter method to see the association between infertility-specific stress and the predictor variables. To eliminate some of the independent variables which were not confounders or associated with the dependent variable, those with P < 0.1 in univariate analysis were considered for inclusion in multiple logistic regression model. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 300 individuals diagnosed with primary infertility participated in the study. 43% of the women were educated up till high-school, 62% were from rural backgrounds, 55% from joint family settings, occupationally 64% of them unemployed and preferentially house-wives belonging to agricultural households, with 50% of them belonging to lower-middle or middle socioeconomic statuses, with family income of 11,000-20,000 INR/month. The women belonged to an age range of 20–49 years (with a median of 29 years) and husbands' age range was 24–54 years (median of 35 years). Marital years ranged between 8 months and 20 years, with a median of 2 years. The duration of infertility ranged from 1 to 20 years. Most of them had taken treatment at a local primary health center or private nursing homes, nearby their residential setups before seeking consultation at our assisted conception unit. The median duration of outside treatment was 1 year (range 0–12 years). A detailed look at the past treatments showed that 45% of them had no history of ovulation induction (OI), 40% had taken 1–3 cycles of OI, and 16% had taken 4–12 cycles of the same. In addition, 88% had taken 1 cycle of intra-uterine insemination (IUI) and 12% had taken 2–16 cycles of same before seeking treatment at our center. Finally, 97% of them were advised but had not taken in vitro fertilization (IVF) mostly due to financial constraints and 3% had taken 1–3 cycles of IVF before their first consultation with us. Interestingly, only 10% of them had received mental health consultations/treatment for distress before. These patients usually travelled from a distance ranging from 10 to 500 km, to seek treatment at our center.

Analyzing the etiology, 30% were known cases of combined factor infertility, 29% had female factor infertility, 25% had male factor infertility, and 15% were found to have unexplained factor infertility. Within female factor infertility, 14% were diagnosed with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), 6% with uterine anomalies (adenomyosis, fibroids, arcuate uterus, septate uterus, unicornuate uterus, and bicornuate uterus), 4% with endometriosis, 4% with ovarian cyst, 4% with tubal factors, and 3% with low ovarian reserve and poor endometrial growth. 78% had no previous history of abdominal or gynecological surgery, 3% had undergone cystectomy, 3% had undergone myomectomy, 2% had undergone laparoscopic ovarian drilling, and 14% had undergone laparoscopic treatments for other gynecological conditions. Within male factor infertility, 15% of males were diagnosed with mild to moderate, 5% with severe oligospermia, oligoasthenospermia, azoospermia or aspermia or teratozoospermia, and 1% with normospermia/absence of urological abnormality. Twenty-one percent of females had other medical morbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, epilepsy, and thyroid disorders.

Prevalence of infertility-specific stress

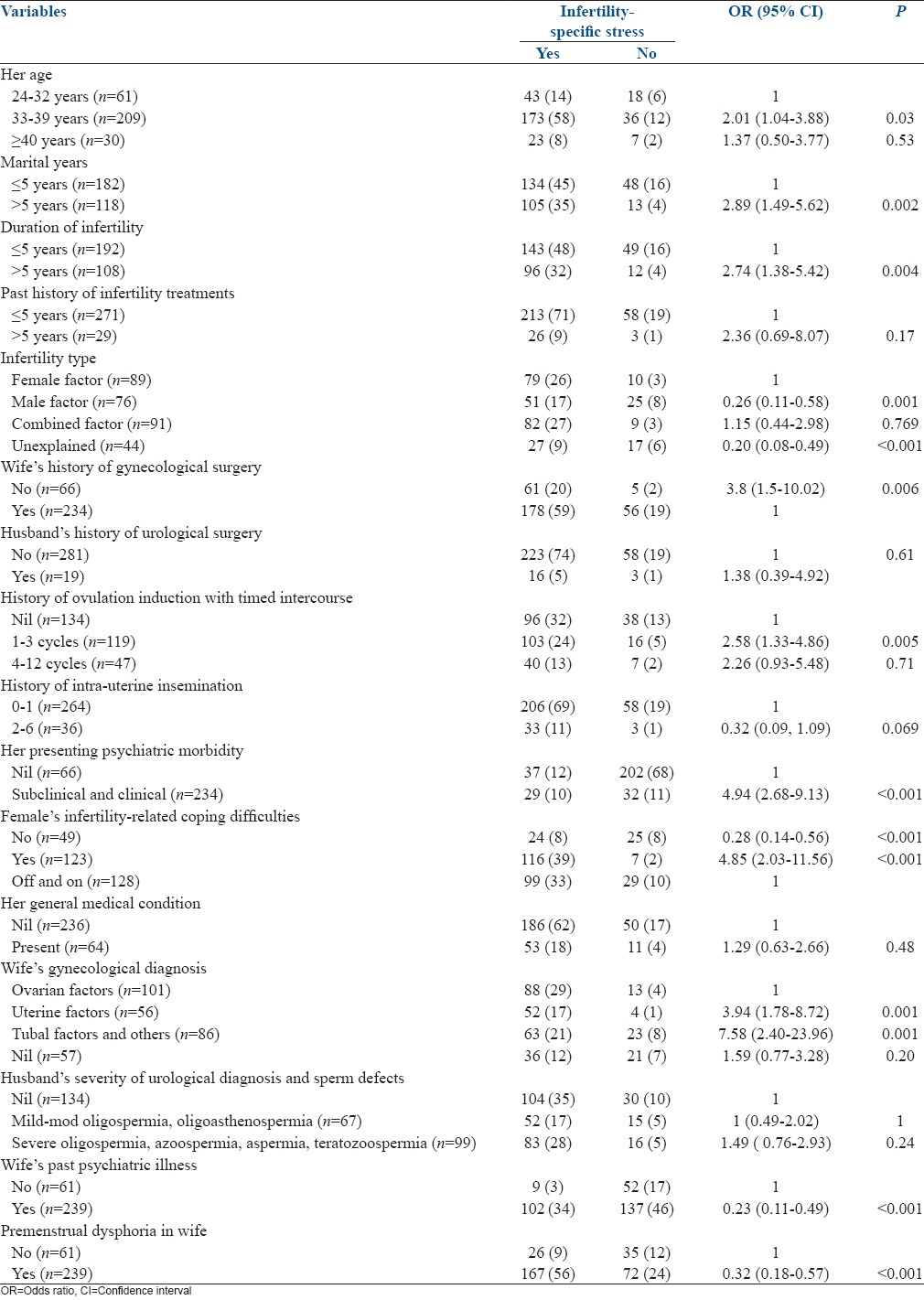

Overall, the prevalence of infertility-specific stress among women was 80% (95% CI, 75.5–84.5%). Chi-square test was used for univariate analysis. The results of univariate regression analysis for associations between current infertility-specific stress and selected factors in females are summarized in Table 1. The table illustrates that odds of infertility-specific stress in women is predicted significantly by variables such as marital years, duration of infertility, infertility type, history of gynecological surgery in women, number of cycles of OI with timed intercourse and IUIs, female's present and past psychiatric morbidity, coping difficulties, gynecological diagnosis, and severity of premenstrual dysphoria.

Table 1.

Univariate analysis for associations between infertility-specific stress in women and selected factors

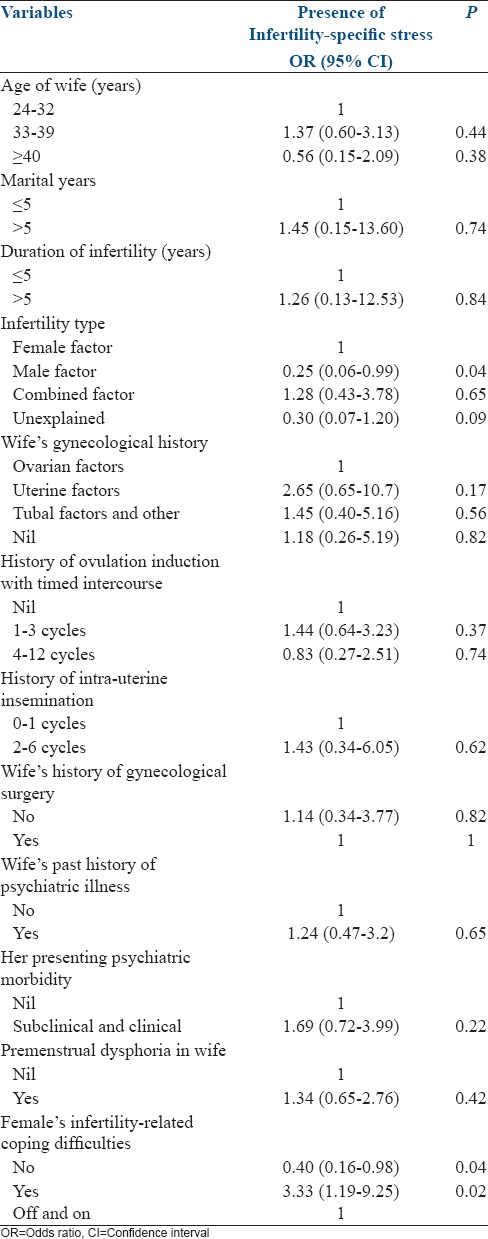

Table 2 presents the results of multiple logistic regression to identify the predictors for infertility-specific stress in women. Several factors were selected for multivariate analysis for determining the predictors of infertility stress in women. However, owing to limitations in sample size, only a few of these were found to be statistically significant. In Table 2, the factors that best predict infertility-specific stress in women diagnosed with primary infertility were infertility type and significant coping difficulties in regard to infertility stressors, experienced by them.

Table 2.

Multiple logistic regression analysis predictors for infertility-specific stress among women

DISCUSSION

Parenthood is one of the major transitions in adult life for both men and women. The psychological sequel of infertility begins from the very diagnosis of it. The stress of the nonfulfillment of a wish for a child has been known to impact the personal, social, familial, financial, and occupational aspects of a couple's life. When a couple experiences infertility, it is common for them to pass through all the known stages of grief and mourning (state of shock, denial, anger, isolation, and finally acceptance). At some point of time, these individuals may have difficulty in acknowledging the grieving process as they may not understand the loss of something that never existed. This has been known to lead again to yet greater isolation, deterioration of the psychological state, and significant effect on reproductive outcomes. Review studies suggest that higher concentrations of stress-induced biological markers provide evidences of the direct effect of stress on fertility outcomes in women. Those with high anxiety, adrenaline, noradrenaline, and cortisol concentrations had lower number of both fertilized oocytes, transferred embryo, rates of implantation, and IVF pregnancies.[5],6,28,[29,30] Accordingly, the present study was designed as a clinic-based research to estimate the prevalence of infertility-specific stress in women diagnosed with primary infertility and also to identify predictors of infertility-specific stress in such patients.

Experience of women

The results of the present study suggest that the likelihood of infertility-specific stress experienced by women is higher when they experience >5 years of married life and in those with >5 years of infertility duration. This was supported by findings of available research reviews.[19] Infertility-specific stress in women was lesser when a diagnosis of male factor infertility is made compared to a situation when a diagnosis of female factor or unexplained infertility is made. Our findings reveal that a diagnosis of uterine and ovarian abnormalities has greater likelihood of causing distress to female patients than a diagnosis of tubal factor abnormalities. Diagnosis of uterine abnormalities is 8 times more distressing and an ovarian abnormality is 4 times more distressing than a condition when no gynecological abnormalities are present. Female infertile patient's experience of gynecological surgery is also stressful. Similar findings have been revealed by another research[19] suggesting that gynecological abnormalities were among the top three reasons for depression and anxiety in infertile women. Those who have undergone laparoscopic surgeries were found to be 4 times more likely to be distressed than those who have not undergone any. The latter has also been supported by available research.[31] In addition, infertility stress is maximum in the initial one to three cycles of treatments (OI with times intercourse) than in later cycles (OI cycles or in intra-IUIs). Results also suggest that in females, there lies a possibility of decreasing infertility stress after repeated cycles of OI and IUI, possibly due to desensitization to stressors or development of better coping mechanisms/social support to deal with the same. This findings is also supported by other studies.[32] Coping difficulties have been significantly associated with infertility-specific stress in females and reported by 84% of the females diagnosed with primary infertility (43% of them experiencing off and on coping difficulties, whereas 41% experience significant coping difficulties). Those with significant coping difficulties experience 5 times greater infertility stress. Moreover, as per the results, healthy coping abilities are one of the major psychological factors that can buffer them from infertility stress, which has also been proven by other researches.[33,34] Likewise, perceived infertility stress and its effects were far less in individuals with adaptive coping abilities.

Chronic stressors in combination with maladaptive coping capacities in women with primary infertility lay the foundations for evolving psychological and psychiatric morbidity. Crosssectionally, data analysis on the history of presenting psychiatric morbidity in females, suggests that 79% of them experienced (clinical [45%] and subclinical [34%]) psychiatric morbidity, at their first consultation at our center. The likelihood of infertility-specific stress in females with psychiatric morbidity was 5 times greater than those with no such morbidity. Furthermore, experience of premenstrual dysphoria in distressed females, undergoing infertility treatments, was greater than those who were nondistressed. In those undergoing assisted reproductive treatment, distress was reported to be at its peak, a week before the expected date of onset of menstrual cycle, as this was the time these women were expecting their pregnancy and treatment results. Results of multiple regression analysis endorses the associations between females' infertility-specific stress and variables such as nature of infertility type (where female factor is more distressing than male factor infertility) and protective effects of adaptive coping capacities in females.

A common feature in the experience of fertility-related stress across all the study participants was that they were more distressed over their own gender-specific infertility diagnosis, surgeries, and reproductive treatment procedures that they undergo than being distressed about their husbands' diagnosis or condition. In a majority of the women, there is a high likelihood that psychological or psychiatric morbidity exists at subclinical or clinically significant levels, although these patients might not always vocalize the same to the infertility expert at their first visit. An interesting finding of the present study was that early emergence of psychiatric morbidity (clinical and subclinical) and prompt intervention for this may protect them from worsening of mental health and stress. In pursuit of the same, the distressed women mentioned that they felt some relief by seeking social support, peer-support, web-based informational support, vocational involvements, early mental health services and consultations, and alternative treatments as reported by them (Yoga, meditation, Reiki, ayurvedic treatments, naturopathy, fail-healing, religious intercessions, and life-style modifications).

The results of this study indicate that sub-fertile women experience emotional trajectories, beginning from the very point at which they decide to conceive till they give birth to their desired child/children. Irrespective of the pregnancy outcomes, a vast body of literature suggests that couples experience these struggles as crisis inducing and taxing. The stressors and stress response may vary form one couple to the other and as a rule of thumb in our setups is mediated by a number of factors such as medical, individual, couple-related, familial, religious, sociocultural, and economic. There can be other psychological variables that predict infertility stress such as personality dispositions, locus of control, appraisal cognitions, illness-specific cognitions, behavioral factors, coping strategies, sociocultural milieu, and support; however, these were uninvestigated in this study and stand as limitations of the present work. Implications of the present study can be understood in the background of the recent epidemiological evidence that presents positive correlations between various pregnancy failure outcomes with preconception stress.[35,36] Addressing stress-related factors with the help of psychological interventions can also relieve preprograming of stress susceptibility in the expecting mother and fetus. Nonetheless, the present work can further be improved on the grounds of study variables, measures used, research design, sample size, and can be expanded to study the psychological issues in culture-specific scenario to include those with secondary infertility, undergoing donor programs, surrogacy, adoption, and others who are treatment drop-outs.

CONCLUSION

The results of the present investigation suggest that there exists a baffling, dynamic, and complex interplay between infertility stress, its predictors, and mediators. Since the prevalence of infertility-specific stress is high in couples seeking assisted reproductive treatments, the routine clinical care of such patients should include psychological/psychiatric consultations to screen them for any such morbidity and treat, if necessary. Identifying the group at-risk of developing such morbidity seems crucial, as this group often comprises of patients who are on the verge of deteriorating physical and mental health and poorer reproductive outcomes. This group of patients should be promptly handled by a trained reproductive psychologist/psychiatrist/psychiatric social worker, using specific evidence-based interventions.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Robbins SP. Essentials of Organizational Behaviour. 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freeman EW, Rickels K, Tausig J, Boxer A, Mastroianni L, Jr, Tureck RW. Emotional and psychosocial factors in follow-up of women after IVF-ET treatment. A pilot investigation. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1987;66:517–21. doi: 10.3109/00016348709015727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guerra D, Llobera A, Veiga A, Barri PN. Psychiatric morbidity in couples attending a fertility service. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:1733–6. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.6.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kee BS, Jung BJ, Lee SH. A study on psychological strain in IVF patients. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2000;17:445–8. doi: 10.1023/A:1009417302758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smeenk JM, Verhaak CM, Vingerhoets AJ, Sweep CG, Merkus JM, Willemsen SJ, et al. Stress and outcome success in IVF: The role of self-reports and endocrine variables. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:991–6. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Csemiczky G, Landgren BM, Collins A. The influence of stress and state anxiety on the outcome of IVF-treatment: Psychological and endocrinological assessment of Swedish women entering IVF-treatment. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:113–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2000.079002113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leader A, Taylor P, Danilak J. Infertility clinical and psychological aspects. Psychiatr Ann. 1984;14:461. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baram D, Tourtelot E, Muechler E, Huang K. Psychosocial adjustment following unsuccessful in vitro fertilization. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 1988;9:181–90. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boivin J, Lancastle D. Medical waiting periods: Imminence, emotions and coping. Womens Health (Lond Engl) 2010;6:59–69. doi: 10.2217/whe.09.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Callan VJ, Kloske B, Kashima Y, Hennessey JF. Toward understanding women's decisions to continue or stop in vitro fertilization: The role of social, psychological, and background factors. J In Vitro Fert Embryo Transf. 1988;5:363–9. doi: 10.1007/BF01129572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Connolly KJ, Edelmann RJ, Cooke ID, Robson J. The impact of infertility on psychological functioning. J Psychosom Res. 1992;36:459–68. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(92)90006-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lancastle D, Boivin J. A feasibility study of a brief coping intervention (PRCI) for the waiting period before a pregnancy test during fertility treatment. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:2299–307. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andrews FM, Abbey A, Halman LJ. Is fertility-problem stress different. The dynamics of stress in fertile and infertile couples? Fertil Steril. 1992;57:1247–53. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)55082-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hynes GJ, Callan VJ, Terry DJ, Gallois C. The psychological well-being of infertile women after a failed IVF attempt: The effects of coping. Br J Med Psychol. 1992;65(Pt 3):269–78. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1992.tb01707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McQuillan J, Greil AL, White LK, Jacob MC. “Frustrated Fertility: Infertility and Psychological Distress Among Women”. Bureau of Sociological Research - Faculty Publications. Paper 13. 2003. [Last accessed on 2015 Apr 28]. Available from: http://www.digitalcommons.unl.edu/bosrfacpub/13 .

- 16.Ogawa M, Takamatsu K, Horiguchi F. Evaluation of factors associated with the anxiety and depression of female infertility patients. Biopsychosoc Med. 2011;5:15. doi: 10.1186/1751-0759-5-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boivin J. A review of psychosocial interventions in infertility. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:2325–41. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00138-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greil AL, McQuillan J, Lowry M, Shreffler KM. Infertility treatment and fertility-specific distress: A longitudinal analysis of a population-based sample of U.S. women. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramezanzadeh F, Aghssa MM, Abedinia N, Zayeri F, Khanafshar N, Shariat M, et al. A survey of relationship between anxiety, depression and duration of infertility. BMC Womens Health. 2004;4:9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-4-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Domar AD, Broome A, Zuttermeister PC, Seibel M, Friedman R. The prevalence and predictability of depression in infertile women. Fertil Steril. 1992;58:1158–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joshi HL, Singh R, Bindu R. Psychological distress, coping and subjective wellbeing among infertile women. J Indian Acad Appl Psychol. 2009;35:329–36. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sudha G, Reddy KS. Emotional distress in infertility couples: A cross sectional study. Asia Pac J Soc Sci. 2011;3:90–101. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Banerjee N, Roy KK, Takkar D. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder – A study from India. Int J Fertil Womens Med. 2000;45:342–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh A, Dhaliwal LK, Kaur A. Infertility in a primary health centre of Northern India: A follow up study. J Fam Welf. 1997;42:51–6. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vayena E, Patrick JR, Griffin DP. Report of Meeting on “Medical, Ethical and Social Aspects of Assisted Reproduction”. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Headquarters; 2001. [Last accessed on 2015 May 12]. Current Practices and Controversies in Assisted Reproduction. Available from: http://www.apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42576/1/9241590300.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franco JG, Jr, Razera Baruffi RL, Mauri AL, Petersen CG, Felipe V, Garbellini E. Psychological evaluation test for infertile couples. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2002;19:269–73. doi: 10.1023/A:1015706829102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Demyttenaere K, Nijs P, Evers-Kiebooms G, Koninckx PR. Coping and the ineffectiveness of coping influence the outcome of in vitro fertilization through stress responses. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1992;17:655–65. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(92)90024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Facchinetti F, Matteo ML, Artini GP, Volpe A, Genazzani AR. An increased vulnerability to stress is associated with a poor outcome of in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer treatment. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:309–14. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(97)81916-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderheim L, Holter H, Bergh C, Möller A. Does psychological stress affect the outcome of in vitro fertilization? Hum Reprod. 2005;20:2969–75. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harlow CR, Fahy UM, Talbot WM, Wardle PG, Hull MG. Stress and stress-related hormones during in-vitro fertilization treatment. Hum Reprod. 1996;11:274–9. doi: 10.1093/humrep/11.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berg BJ, Wilson JF. Psychological functioning across stages of treatment for infertility. J Behav Med. 1991;14:11–26. doi: 10.1007/BF00844765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stanton AL, Tennen H, Affleck G, Mendola R. Coping and adjustment to infertility. J Soc Clin Psychol. 1992;11:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Terry DJ, Hynes GJ. Adjustment to a low control situation: Re-examining the role of coping responses. J Pers Soc Psychiatry. 1998;74:1078–92. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakamura K, Sheps S, Arck PC. Stress and reproductive failure: Past notions, present insights and future directions. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2008;25:47–62. doi: 10.1007/s10815-008-9206-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zaig I, Azem F, Schreiber S, Gottlieb-Litvin Y, Meiboom H, Bloch M. Women's psychological profile and psychiatric diagnoses and the outcome of in vitro fertilization: Is there an association? Arch Womens Ment Health. 2012;15:353–9. doi: 10.1007/s00737-012-0293-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]