Abstract

Home health aides are members of a rapidly growing occupation and often develop close ties to patients and their family and can experience significant grief when a patient dies. Yet agencies often provide little support or structure to help staff cope during this time. For instance, home care agencies do not always notify their staff of client death and some have policies in place to prevent any follow-up contact with a deceased client’s family. Little is known about how these agency factors affect HHAs’ work experience. This mixed-method study explored the experiences of 78 HHAs working either at an agency with a restrictive policy regarding contact with a client’s family after client death or an agency without such a policy in place. Data was collected through semi-structured in-person interviews. Employment outcomes included various aspects of job satisfaction and intention to change jobs. HHAs’ responses to client death were assessed with measures of grief and grief processing, and with open-ended questions exploring their experiences in this context. Findings indicated that HHAs from the restrictive agency were significantly more likely to be considering other job options. They also reported significantly lower satisfaction with received supervision, and significantly less grief processing activity. Findings suggest that HHAs from the agency without a contact restrictive policy had a more positive experience at work and more opportunity to process the client’s death.

Introduction

An increasing percentage of older adults wish to be cared for in their homes, resulting in a rise in the need for home care services for this group. Home health aides (HHAs) provide the bulk of the direct care provided in the home. They are members of one of the fastest growing fields, ranking third on the list of fastest growing occupations with an expected growth of 48% between 2012 and 2020 (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014-15). Though this sector of long term care is quickly expanding, there remain challenges for this critical workforce. Turnover rates among HHAs are particularly high (Stone, 2004), falling between 35% and 65% per year (Dill & Cagle, 2010; Seavey & Marquand, 2011). In addition, job dissatisfaction is regularly reported. Dissatisfaction on the job is an important employment outcome because it is correlated with high rates of burnout, low self-esteem, depression, and anxiety (Faragher, Cass, & Cooper, 2005). Finding ways to improve employee retention and job satisfaction is a significant priority in the field.

HHAs work very closely with their older patients, providing care that is intimate and personal (Stone, 2004). The nature of this work often results in the development of close relationships with patients (Piercy, 2000; Butler & Rowan, 2013; Stacey, 2005; Denton, Zeytinoglu & Davies, 2008). For some HHAs this opportunity to develop interpersonal relationships is one of the major reasons they came into the field and continue to remain on the job (Denton et al., 2008; Sims-Gould, Byrne, Craven Martin-Matthews & Keefe, 2010).

Research evidence has shown that HHAs who develop close ties to the patients and their families experience significant grief when a patient dies (Boerner, Burack, Jopp, & Mock, 2015). Yet, the grief reaction of direct care staff has been recognized as one form of “disenfranchised grief” (Moss & Moss, 202). HHAs may also have a role in comforting the family in the initial aftermath of the patient’s death. McClement and colleagues reported from their study on HHA perspectives on care of dying patients that HHAs considered conveying their sympathy to family members after the death and appreciating the family’s need to reminisce as important tasks in providing high quality care (McClement, Wowchuk, & Klaasen, 2009). However, home care agencies often do not have adequate protocols or structures in place to support their staff members in the context of patient death (Moss & Moss, 2002). For example, home care agencies do not always notify their staff of a patient’s death and some have policies in place to prevent any follow-up contact with a deceased patient’s family. Little is known about how these types of agency factors affect HHAs’ work experience.

The study compares a home care agency with a restrictive contact policy (no follow-up after death allowed) with one that has no such policy. Our first aim was to test the hypothesis that HHAs employed by agencies with restrictive policies would be more likely to consider other career options, and more likely to be less satisfied with their job. Our second and third aims were explorative: We examined whether HHAs differed with regard to other key outcomes of the study, including relationship to patient and family, caregiving benefits experienced at work, and their grief symptoms and grief processing after the patient’s death. Finally, we explored responses from open-ended questions throughout the interview for comments pertaining to policy/instructions to illustrate HHA perceptions and reactions.

METHODS

Recruitment and eligibility

The present analysis is part of a larger mixed-methods study that looked at bereavement in direct care workers (Barooah, Boerner, Riesenbeck, & Burack, 2015; Boerner et al., 2015; Riesenbeck, Boerner, Barooah, & Burack, 2015). We recruited actively employed HHAs from the community service division of an elder care system in Greater New York, and two other agencies subcontracted by this long-term care organization. HHAs had to have experienced the death of a patient for whom they were the permanent HHA within approximately two months to be eligible. The participating agencies’ administrative staff informed us when patient deaths occurred and asked the primary HHA of the deceased patient if it was permissible for study personnel to contact them. If the HHA agreed, study staff followed up with a phone call to explain the study and schedule an interview. Since English language proficiency was not a job requirement for HHAs and the pool of potential participants included individuals whose primary language was Spanish, HHAs could choose to complete the interview in Spanish. Of a total of 122 HHAs we attempted to reach, 38 could not be reached within two months of the patient’s death, 80 out of the 84 we were able to reach agreed to participate and the other four refused. Thus, the overall response rate was 95%. The participating HHAs were representative of the larger pool of HHAs serving the organization’s patients with regard to age, gender and tenure. However, when compared by race/ethnicity, we found a difference in the proportion of Black and Hispanic HHAs. Our study sample was 67% Black and 29% Hispanic, whereas the larger pool of HHAs was 33% Black and 64% Hispanic.

We did not purposefully choose agencies based on their policies regarding follow up contact or inquiry about patient death. However, over the course of data collection, HHA accounts of their experience after patient death alerted us to this issue. We subsequently reviewed the participating organizations’ relevant policies, and found that we had included one agency with a concrete policy not to have any follow-up contact in place (n=40), one agency with no such policy in place (n=38), and one agency that would not specify a relevant policy (n=2). Since we had only two participants from the latter agency, we decided to focus on comparing the two agencies with clear positions re: follow-up contact/inquiry after patient death; thus the final sample for the present paper was N=78.

Data Collection and Measures

The one-on-one interviews were conducted in-person by trained interviewers with a Bachelor’s or Master’s degree. Interviews were conducted at a place and time that was convenient to the participant and lasted an average of 80 minutes. Prior to all interviews, written informed consent was obtained and participants received $30 for their time. Interviews were never conducted during the HHAs’ work hours.

Socio-demographic and background characteristics assessed included gender, age, education, ethnicity, race, and marital status. Additionally noted were numbers of years worked as HHA, number of months having cared for the deceased patient, and the time between the interview and the patient’s death. HHAs’ possible intention to leave the job was assessed with a single-item: “Taking everything into consideration, how likely is it you will try to pursue a different line of work within the next year?” (5) very likely - not likely at all (1).

Job satisfaction was assessed with a short-version of the Job Description Index (JDI) (Smith, Kendall, & Hullin, 1969), a popular and widely used measure of job satisfaction. This measure consists of six subscales: work, pay, promotion, supervision, coworkers (6 items each), and general satisfaction (8 items). Standard scoring for the JDI was used. Cronbach alpha for the subscales in the present study ranged from .70 - .87.

Relationship with patient was assessed on a scale measuring rewarding aspects in the relationship between caregiver and care recipient (Williamson & Shaffer, 2001). HHAs were asked how often (a) they felt happy with their relationship with the patient, (b) the patient made them feel good about themselves, (c) they felt very emotionally close to the patient, (d) they felt bored with the patient (4-point Likert scale; never-always). Scores indicated the extent to which the relationship is perceived as rewarding. Cronbach alpha in the present study was .76.

Positive aspects of caregiving were assessed with an 11-item scale that has demonstrated excellent psychometric properties and has emerged as a strong predictor of bereavement outcomes in previous studies of family caregiving and bereavement (e.g., Schulz, Boerner, Shear, Zhang, & Gitlin, 2006). Items reflect caregiving benefits such as “made me feel useful” or “enabled me to appreciate life more” (5-point Likert scale; disagree a lot - agree a lot). Higher scores indicated greater caregiving benefit. Cronbach alpha in the present study was .78.

Grief symptoms were assessed with the 13-item version of the Texas Revised Inventory of Grief (Faschingbauer, Zisook, & DeVaul, 1987), a validated scale to assess current symptoms associated with separation distress. Responses ranged from (1) completely false to (5) completely true. This scale has been successfully used in large national bereavement studies (e.g., Boerner, Schulz, & Horowitz, 2004; Schulz et al., 2006) and thus is suitable for comparison with the family bereavement literature. Cronbach alpha in the present study was .76.

Grief processing was assessed with a scale developed and validated by Bonanno and colleagues (Bonanno, et al., 2005). This scale measures 5 thoughts and behaviors (e.g., thinking about the deceased, having positive memories, and talking about the deceased). All items are rated on a 5-point scale for frequency of occurrence (almost never - almost constantly). Cronbach alpha in the present study was .88.

Open-ended questions exploring HHA’s experience after patient death to which HHAs provided responses related to the contact restrictive policy included inquiry about how they responded to hearing about the death, how they felt about how they were notified about the death, how they felt about how their reassignment to a new case was handled, what kinds of interactions they had with the patient’s family after the death, what, if any, training regarding death and dying they got from their employer, what kind of rituals took place after the death and if they participated, and what kind of acknowledgement of patient death they would like the agency to have in place. A coding system for the open-ended data was developed with an analytical theme-identification approach often used in qualitative analysis (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Miles, Huberman, & Saldana, 2014). Kappa coefficients consistently ranged from .75 to 1 (average kappa = .92), demonstrating adequate interrater agreement (for a more detailed description of the coding process, see Barooah et al., 2015).

Findings

Descriptives of sample characteristics and major study variables are displayed in Table 1. Participating HHAs were mostly women reflecting the larger population of HHAs. About one third identified as Hispanic and two thirds of the sample identified as Black. Most HHAs were high school graduates or had at least some college. Almost one third indicated being married or living as married, another third being divorced or separated, and a little more than a third reported having never been married. About half of HHAs reported never having experienced a patient death before. On average the HHAs had been working in the profession for 6 to 7 years and cared for their deceased patient for 18 months.

Table 1. Descriptive Information on Sample Characteristics (N=80).

| Mean (SD) | Range | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (Female) | 77 (96) | ||

| Age | 43.2 (12.5) | 24-69 | |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic) | 23 (29) | ||

| Race | |||

| Black | 52 (67) | ||

| White | 8 (10) | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander/ Native American |

3 (4) | ||

| Other | 15 (19) | ||

| Education | |||

| Grades 7-9 | 8 (10) | ||

| Grades 10-11 | 8 (10) | ||

| GED | 4 (5) | ||

| HS graduate | 25 (31) | ||

| Some college/graduate | 34 (42) | ||

| Marital status | |||

| Married/living as married | 23 (29) | ||

| Divorced/separated | 24 (30) | ||

| Widowed | 2 (3) | ||

| Never married | 31 (39) | ||

| Years working as a HHA | 6.5 (6.6) | .16-29 | |

| Months since client’s death | 1.08 (.98) | 0-3 | |

| Months cared for client | 18 (29) | .03-168 |

Findings from group comparisons are depicted in Table 2. Addressing aim 1, HHAs from the agency with a contact-restrictive policy were significantly more likely to express an intention to consider other job options within the next year, as expected. They were also likely to report significantly lower job satisfaction with respect to one of the six subscales, supervision received in the work place. Four other subscales also indicated lower satisfaction scores for this group (tasks at work, people at work, promotion options, and general satisfaction), however these differences were not substantial enough to reach significance. The only subscale with almost identical means was satisfaction with pay, which was visibly low in both groups.

Table 2. Mean Differences in Relationship, Grief, and Employment Outcomes by Homecare Agency Group.

| Agency with restrictive policy |

Agency without restrictive policy |

Significance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| M (SD) | Range | M (SD) | Range | F-value | P-value | |

| HHA-client relationship | 2.70 (1.4) | 0-4 | 2.87 (1.3) | 0-4 | .29 | .59 |

| Caregiving benefits | 9.25 (2.2) | 3-11 | 9.79 (2.0) | 4-11 | 1.32 | .26 |

| Grief symptoms | 31.28 (12.6) | 13-65 | 34.59 (11.9) | 14-61 | 1.41 | .24 |

| Grief processing | 13.23 (4.8) | 5-25 | 15.61 (4.2) | 7-23 | 5.43 | .02 |

| Intention to leave job | 3.00 (1.1) | 1-4 | 2.26 (1.3) | 1-4 | 7.35 | .008 |

| Job satisfaction: | ||||||

| Supervision | 10.88 (5.9) | 0-18 | 13.53 (5.5 | 0-18 | 4.20 | .04 |

| Work | 14.03 (4.6) | 0-18 | 15.03 (4.3) | 3-18 | .99 | .32 |

| Coworkers | 12.92 (5.1) | 3-18 | 14.19 (5.3) | 0-18 | 1.11 | .29 |

| Promotion | 7.20 (5.8) | 0-18 | 7.57 (6.0) | 0-18 | .08 | .79 |

| Pay | 4.90 (1.6) | 0-6 | 4.97 (1.7) | 0-6 | .04 | .84 |

| General | 16.40 (6.9) | 0-24 | 18.61 (5.3) | 3-24 | 2.51 | .11 |

Note. Agency with restrictive policy n = 40; agency without restrictive policy n = 38.

To be able to put the employment outcome findings in the larger context of the HHAs’ experience, we additionally conducted group comparisons for key relationship, caregiving, and grief outcomes (see Table 2). While there were no group differences with regard to perceived HHA-patient relationship quality, caregiving benefits experienced in the workplace, or grief symptoms after patient death, HHAs from the agency with a contact-restrictive policy reported significantly less grief processing activity (thinking and talking about the death). Thus, findings suggest that HHAs from the two agencies were similar with respect to the closeness of their relationship to their patient and the sense of meaning or purpose derived from their caring role, but despite these similarities, the HHAs from the agency with a contact-restrictive policy may have had fewer options for exchange and processing of this experience.

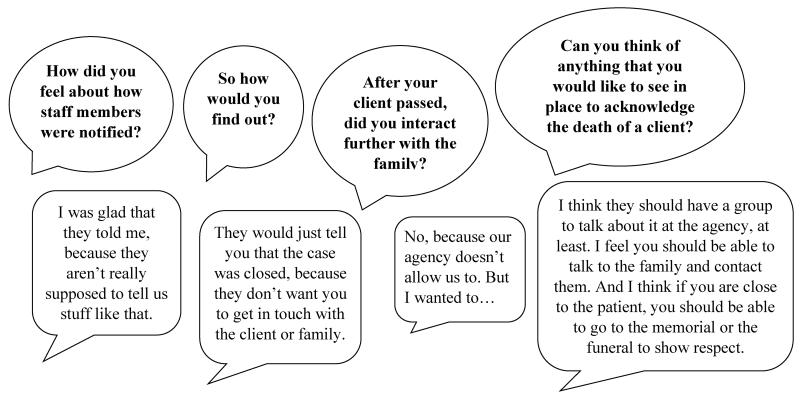

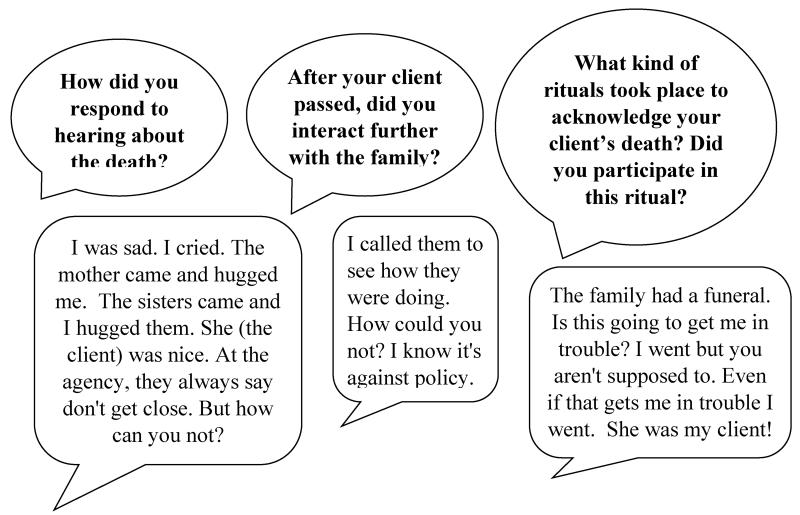

Finally, to give voice to the experiences of HHAs from the agency with contact restrictive policy, we carefully examined all responses to open-ended questions throughout the interview for this group. Narrative accounts indicated that HHAs had developed a close relationship with patients and family and they perceived their agency’s restrictive policy regarding follow-up contact after patient death as problematic. When talking about this, they also sought reassurance from us that the interview is confidential. Specifically, some reported that they would have liked to have had such contact, to offer condolences or attend a funeral, but abided by the agency policy (example displayed in Figure 1), whereas others decided to go against the policy and make contact with the family after patient’s death (example displayed in Figure 2).

Figure 1. HHA abided by policy and did not contact family.

Figure 2. HHA went against policy and made contact with family after client death.

Discussion

Overall, study findings suggest that HHAs from the agency without a contact-restrictive policy had a more positive experience at work and more opportunity to process the patient’s death. This is a tentative conclusion as we were not able to directly test if variance in employment outcomes is related to policy differences. It is however notable that the groups can be characterized by differences on these outcomes, whereas similar differences do not emerge for other key variables (e.g., relationship with patient or grief). Moreover, narrative responses throughout the interviews in response to various interview questions reflected HHAs’ perceptions that policy plays a role in their experience, and that the contact restriction is perceived as a negative factor in their work life. That this theme was so present in HHAs’ accounts despite the fact that we had not specifically asked about it is also remarkable.

Homecare agencies with similar restrictive policies around patient death may want to consider reviewing such policies and their possible impact on employees. Another important question in this context not addressed in the present study may be how family members experience the situation when an aide who has cared for their loved one does not seek any contact after the death. A closer look at policies and protocols related to patient death and dying in home care may benefit HHAs and their agencies by addressing a source of dissatisfaction and discomfort among employees, and at the same time, nurture an environment where patients and families feel cared for in a compassionate way.

It is also important to note that working in a restrictive-policy environment may impact the HHA’s relationship with their supervisor, as well as their overall perception of the agency in which they work. Previous research has found that the quality of the supervisory relationship, as assessed by the direct care worker, can be an important predictor of overall job satisfaction and retention (Bishop, et al, 2008; Chou, 2012; Decker, Harris-Kojetin, & Bercovitz, 2009). Additionally, feeling supported by the agency and facility where they work, has also been found to influence direct care worker job satisfaction and, when positive, to lower turnover (Bowers, Esmond, & Jacobson, 2003; Eaton, 2001). If HHAs are experiencing a negative reaction due to the way that their supervisor and agency are handling the death of their patient, it has the potential to threaten the quality of these critical relationships and in turn, impact HHAs’ satisfaction on the job and even their decision to remain in their position.

This article presents results on a topic that has rarely been examined and thus deserves greater attention and study. With the instability present in the home care workforce, particularly related to turnover, gaining a better understanding of agency policies that may be impacting HHA satisfaction is important for improving the working conditions of these workers. Though this particular facet of the described study was exploratory, it brings to light an issue that requires additional research. Further exploration into agency policies as they relate to patient death, family contact, and other interactions during critical transition times are needed to better understand the effect on the direct care workforce.

Suggested callouts.

Turnover rates among HHAs are particularly high falling between 35% and 65% per year.

Research evidence has shown that HHAs who develop close ties to the patients and their families experience significant grief when a patient dies

HHAs from the agency with a contact-restrictive policy were significantly more likely to express an intention to consider other job options within the next year, as expected

Narrative accounts indicated that HHAs had developed a close relationship with patients and family and they perceived their agency’s restrictive policy regarding follow-up contact after patient death as problematic

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts on interest

References

- Barooah A, Boerner K, Riesenbeck I, Burack OR. Nursing home practices following resident death: The experience, of Certified Nursing Assistants. Geriatric Nursing. 2015 Dec 29; doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2014.11.005. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2014.11.005. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop CE, Weinberg DB, Leutz W, Dossa A, Pfefferle SG, Zincavage RM. Nursing assistants’ job commitment: Effect of nursing home organizational factors and impact on resident well-being. The Gerontologist. 2008;48:36–45. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.supplement_1.36. Special Issue I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerner K, Burack OR, Jopp D, Mock SE. Grief after patient death: Direct care staff in nursing homes and homecare. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2015;49(2):214–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.05.023. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.05.023. Epub 2014 Jul 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerner K, Schulz R, Horowitz A. Positive aspects of caregiving and adaptation to bereavement. Psychology and Aging. 2004;19:668–675. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.4.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Papa A, Lalande K, Zhang N, Noll JG. Grief processing and deliberate grief avoidance: a prospective comparison of bereaved spouses and parents in the United States and the People’s Republic of China. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(1):86. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers BJ, Esmond S, Jacobson N. Turnover reinterpreted: CNAs talk about why they leave. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2003 Mar;29(3):36–43. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20030301-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. U.S. Department of Labor . Occupational Outlook Handbook. 2014-15 Edition. Home Health Aides; 2014. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/home-health-aides.htm#tab-6. [Google Scholar]

- Butler SS, Rowan N. Supporting home care aides: What employers can do to assist their workers. Home Healthcare Nurse. 2013;31(10):546–552. doi: 10.1097/01.NHH.0000436224.22906.86. doi: 10.1097/01.NHH.0000436224.22906.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou RJ. Resident-centered job satisfaction and turnover intent among direct care workers in assisted living: A mixed-methods study. Research on Aging. 2012;34(3):337–364. [Google Scholar]

- Decker FH, Harris-Kojetin LD, Bercovitz A. Intrinsic job satisfaction, overall satisfaction, and intention to leave the job among nursing assistants in nursing homes. The Gerontologist. 2009;49(5):596–610. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton MA, Zeytinoglu IU, Davies S. Working in patients’ homes: The impact on the mental health and well-being of visiting home care workers. Home Health Care Service Quarterly. 2008;21(1):1–27. doi: 10.1300/J027v21n01_01. doi: 10.1300/J027v21n01_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dill JS, Cagle J. Caregiving in a patient’s place of residence: Turnover of direct care workers in home care and hospice agencies. Journal of Aging and Health. 2010;22(6):713–33. doi: 10.1177/0898264310373390. doi: 10.1177/0898264310373390. Epub 2010 Jun 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton SC. Appropriateness of minimum nursing staffing ratios in nursing homes. Phase II, Final Report. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; Dec, 2001. Retrieved from http://www.theconsumervoice.org/sites/default/files/advocate/policy-resources/CMS-Staffing-Study-Phase-II.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Faragher EB, Cass M, Cooper CL. The relationship between job satisfaction and health: a meta-analysis. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2005;62(2):105–112. doi: 10.1136/oem.2002.006734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faschingbauer TR, Zisook S, DeVaul RA. The Texas Revised Inventory of Grief. In: Zisook S, editor. Biopsychosocial aspects of bereavement. American Psychiatric Press; Washington, DC: 1987. pp. 111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Wiedenfeld and Nicholson; London: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- McClement S, Wowchuk S, Klaasen K. “Caring as if it were my family”: Health care aides’ perspectives about expert care of the dying resident in a personal care home. Palliative and Supportive Care. 2009;7(04):449–457. doi: 10.1017/S1478951509990459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 3rd Ed. Sage Publications; Washington, DC: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Moss MS, Moss SZ. Nursing home staff reactions to resident deaths. In: Doka KJ, editor. Disenfranchised grief: New directions, challenges, and strategies for practice. Research Press; Champaign, IL: 2002. pp. 197–216. [Google Scholar]

- Piercy KW. When it is more than a job: close relationships between home health aides and older patients. Journal of Aging and Health. 2000;12(3):362–387. doi: 10.1177/089826430001200305. 10.1177/089826430001200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riesenbeck I, Boerner K, Barooah A, Burack OR. Coping with patient death: How prepared are home health aides and what characterizes preparedness. Home Healthcare Services Quarterly. 2015 Oct 23; doi: 10.1080/01621424.2015.1108890. doi: 10.1080/01621424.2015.1108890. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Boerner K, Shear K, Zhang S, Gitlin LN. Predictors of complicated grief among dementia caregivers: a prospective study of bereavement. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;14:650–658. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000203178.44894.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seavey D, Marquand A. Caring in America: A comprehensive analysis of the nation’s fastest-growing jobs: Home health and personal care aides. Paraprofessional Healthcare Institute; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sims-Gould J, Byrne K, Craven C, Martin-Matthews A, Keefe J. Why I became a home support worker: Recruitment in the home health sector. Home Health Care Services Quarterly. 2010;29(4):171–194. doi: 10.1080/01621424.2010.534047. doi: 10.1080/01621424.2010.534047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith OC, Kendall LM, Hullin CL. The measurement of satisfaction in work and retirement. Rand McNally; Chicago: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Stacey CL. Finding dignity in dirty work: The constraints and rewards of low-wage home care labour. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2005;27(6):831–854. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2005.00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone RI. The direct care worker: The third rail of home care policy. Annual Review of Public Health. 2004;25:521–537. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.102802.124343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson GM, Shaffer DR, The Family Relationships in Late Life Project Relationship quality and potentially harmful behaviors by spousal caregivers: how we were then, how we are now. Psychology and Aging. 2001;16(2):217–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]