Abstract

Background:

Patients with psoriasis might be at a higher risk of developing Parkinson's disease (PD) as a result of the detrimental effect of chronic inflammation on the neuronal tissue. This meta-analysis aimed to investigate this risk by comprehensively reviewing all available data.

Methods:

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort and case–control studies that reported relative risk, hazard ratio, odds ratio, or standardized incidence ratio comparing the risk of PD in patients with psoriasis versus subjects without psoriasis. Pooled risk ratio and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated using random-effect, generic inverse variance methods of DerSimonian and Laird.

Results:

Three retrospective studies and one case–control study met our eligibility criteria and were included in this meta-analysis. The pooled risk ratio of PD in patients with psoriasis versus participants without psoriasis was 1.38 (95% CI, 1.15–1.66). The statistical heterogeneity was low with an I2 of 35%.

Conclusions:

Our meta-analysis demonstrated a statistically significant increased risk of PD among patients with psoriasis.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Parkinson's disease, psoriasis, risk factor

What was known?

Psoriasis is associated with an increased risk of several co-morbidities, but the data on Parkinson's disease is less clear.

Introduction

Parkinson's disease (PD) is one of the most common neuro-degenerative disorders characterized by tremor, bradykinesia, rigidity and postural instability as well as several nonmotor features including dementia and depression.[1] The estimated worldwide prevalence of PD is 0.3% in individuals over 40 years old.[2,3] The histopathological hallmark of PD is selective degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the brain. The exact pathophysiology of the disease is largely unknown though oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction are generally believed to play a critical role.[4,5] Therefore, chronic inflammatory state might increase the risk of PD. In fact, several epidemiologic studies have demonstrated an increased risk of dementia, another neuro-degenerative disorder, among patients with chronic autoimmune inflammatory diseases.[6,7,8]

Psoriasis is a common immune-mediated skin disorder with an estimated prevalence of 2–4% in the adult population.[9] Patients with psoriasis are well-known to have a high prevalence of comorbidities, especially metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular diseases.[10,11,12] Chronic inflammation is believed to play a pivotal role for this increased risk as several studies have illustrated the unfavorable effect of oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokines on endothelial function, resulting in premature atherosclerosis.[13,14,15]

In light of chronic inflammation, patients with psoriasis might also be at an increased risk of developing PD. Nevertheless, data on this association are limited. Thus, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies to investigate if the risk of PD is increased in patients with psoriasis compared with nonpsoriasis participants.

Methods

Search strategy

Two investigators (Patompong Ungprasert and Narat Srivali) independently searched published articles indexed in MEDLINE and EMBASE database from inception to October 2015 using the search terms that comprised the terms for psoriasis and PD described in Supplementary Data (44.5KB, pdf) . There was no language restriction. References of selected articles were also manually searched.

Inclusion criteria

The eligibility criteria included the following: (1) Cohort study or case–control study comparing the risk of PD between subjects with and without psoriasis, (2) relative risk (RR), hazard ratio, incidence ratio (IR), odds ratio (OR) or standardized IR with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) or sufficient raw data to calculate these ratios were provided.

Study eligibility was independently determined by the two aforementioned investigators. The senior investigator (Wonngarm Kittanamongkolchai) served as the deciding vote for any different decisions. Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment scale was used to assess the quality of the included studies.[16] This scale assessed each study in three areas including (1) the recruitment of the subjects (2) the comparability between the two groups and (3) the ascertainment of the outcomes of interest and exposures of interest for cohort study and case–control study, respectively.

Data extraction

A standardized data collection form was used to extract the following information: First author's last name, title of the study, year of publication, year of study, country where the study was conducted, study population, method used to identify cases and controls, number of subjects, average duration of follow-up (for cohort study), demographic data of subjects, confounders that were adjusted and adjusted effect estimates with 95% CI.

Patompong Ungprasert and Narat Srivali independently performed this data extraction. Any discrepancies were resolved by referring back to the original articles. If the necessary data were not provided in the article, the corresponding author of the article would be contacted.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using Review Manager 5.3 software from the Cochrane Collaboration (London, United Kingdom). We pooled the point estimates from each study using the generic inverse variance method of DerSimonian and Laird.[17] As the outcome of interest in this study was relatively uncommon, we used OR of case–control study as an estimate for RR to combine this data with RR of cohort study to increase the power and precision of our pooled estimates. We used a random-effect model rather than a fixed-effect model because of the high likelihood of between-study variance due to different populations and study designs. Cochran's Q test, which is complemented with the I2 statistic, was used to assess statistical heterogeneity. This I2 statistic quantifies the proportion of total variation across studies that is due to true heterogeneity rather than chance. A value of I2 of 0–25% represents insignificant heterogeneity, more than 25% but ≤50% low heterogeneity, more than 50% but ≤75% moderate heterogeneity, and more than 75% high heterogeneity.[18] Funnel plot and Egger's linear regression were used for evaluation of publication bias using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis version 2.2 software (Englewood, New Jersey, USA).

Results

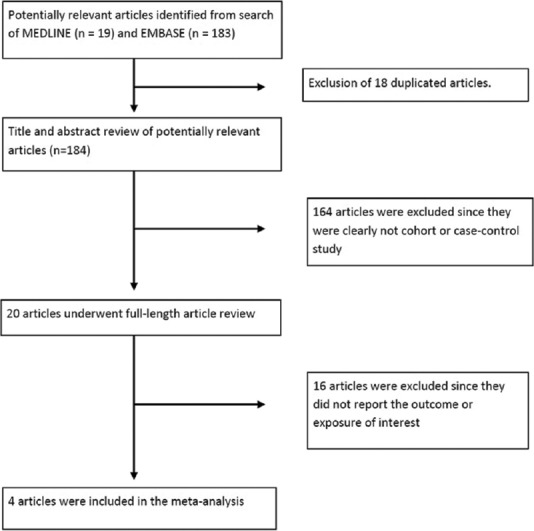

Our search strategy yielded 202 potentially relevant articles (183 articles from EMBASE and 19 articles from MEDLINE). After exclusion of 18 duplicated articles, 184 articles underwent title and abstract review. One hundred and sixty four articles were excluded at this stage since they were case reports, review articles, correspondences or interventional studies, leaving 20 articles for full-length article review. Sixteen of these articles were excluded after the full-length review as they did not report the exposure or outcome of interest, leaving three retrospective cohort studies and 1 case–control study for the meta-analysis.[19,20,21,22] Figure 1 outlines the search and literature review process. The clinical characteristics and quality assessment of the included studies are described in Table 1. The inter-rater agreement for the quality assessment was high with the kappa statistics of 0.64.

Figure 1.

Search methodology and literature review process

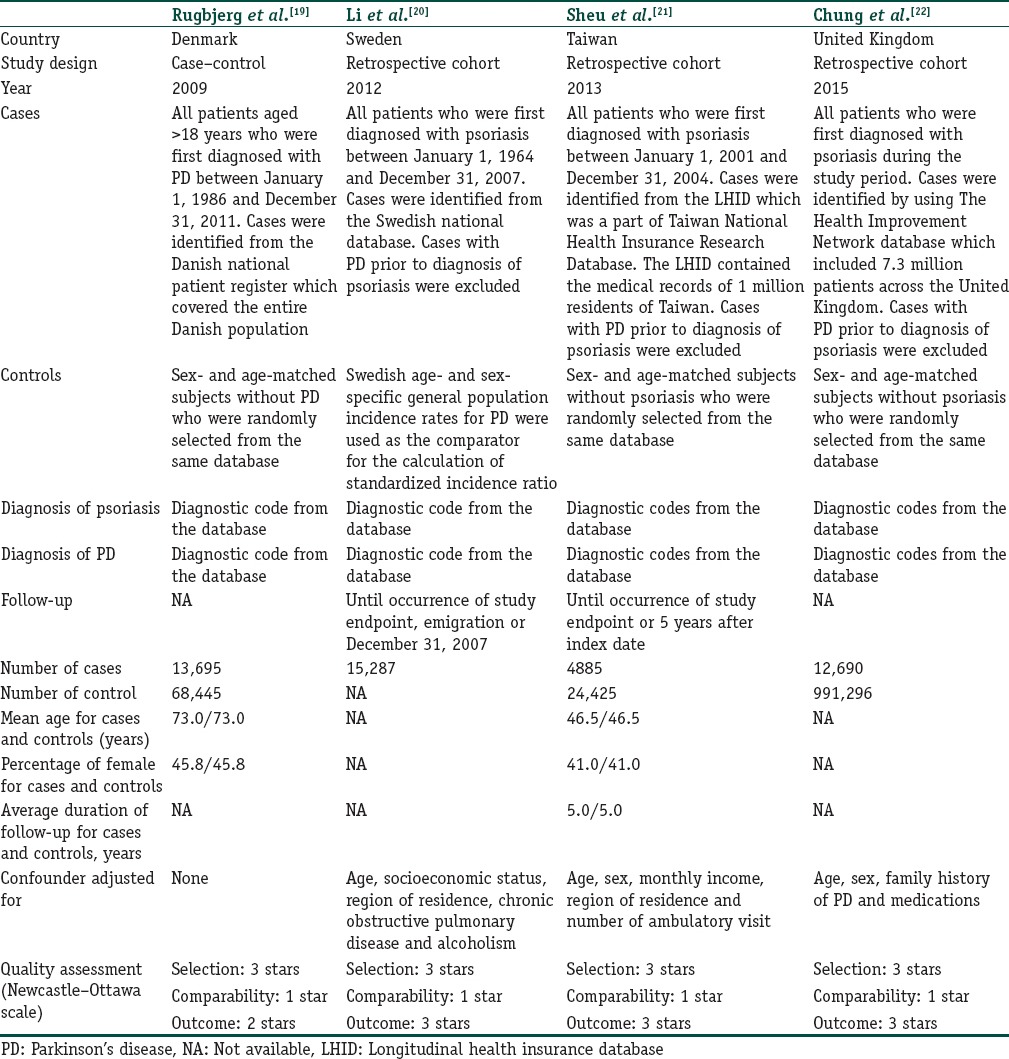

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and quality assessment of the included studies

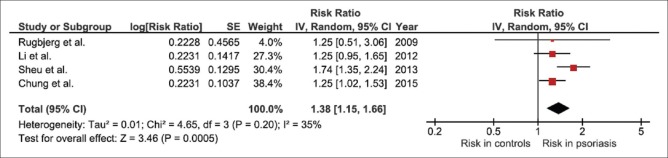

All studies did reveal an increased risk of PD among patients with psoriasis even though the increased risk did not always reach statistical significance. The pooled analysis of all studies demonstrated a significantly increased risk of PD in patients with psoriasis with the pooled risk ratio of 1.38 (95% CI, 1.15–1.66). The statistical heterogeneity was low with an I2 of 35%. The forest plot of the full analysis is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of this meta-analysis

To confirm the robustness of our results, we performed jackknife sensitivity analysis by excluding one study at a time from the pooled analysis. The pooled risk ratios from this sensitivity analysis changed slightly, ranging from 1.25 to 1.47 with the lower bounds of the corresponding CIs remained above 1.0.

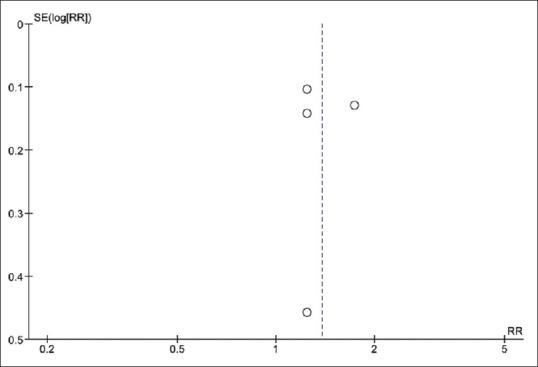

Evaluation for publication bias

Funnel plot to evaluate publication bias is demonstrated in Figure 3. The graph is symmetric and, therefore, is not suggestive of publication bias. Furthermore, there was no evidence of publication bias detected by Egger's regression test (P = 0.72).

Figure 3.

Funnel plot of this meta-analysis

Discussion

This meta-analysis is the first study that comprehensively combined all available data on the risk of PD among patients with psoriasis. We were able to demonstrate a significantly elevated risk with 38% excess risk compared with subjects without psoriasis.

Why patients with psoriasis have a higher risk of PD remains unclear and therefore, further studies are required. There are few possible explanations.

First, this association might be just the result of confounding by obesity as obesity is associated with both psoriasis and PD. High body mass index has been shown to increase the risk of PD in a dose-dependent manner in a recent epidemiologic study[23] while the relationship between obesity and psoriasis has been recognized for over a decade.[24] A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies published between 1980 and 2012 showed the pooled OR for obesity for patients with psoriasis compared with subjects without psoriasis of 1.66.[25] Moreover, the odds for obesity were more prominent in patients with severe psoriasis than those with mild psoriasis. It is hypothesized that the cytokines and bioactive products such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-6, leptin and resistin produced by adipose tissue could predispose patients to psoriasis.[26]

The second explanation is related to chronic inflammation that is seen in patients with psoriasis. As previously mentioned, chronic peripheral inflammation could have an essential role in the development of neuro-degenerative diseases. It has been demonstrated that peripheral inflammation can induce microglial activation, resulting in liberation of free radical/reactive oxygen species and, ultimately, neuronal damages.[21,27,28] The microglial-mediated neurotoxicity is of particular importance for the development of PD as substantia nigra pars compacta, the principal pathological region of PD, has the highest density of microglial cells compared with other parts of the brain.[29] In fact, animal models and postmortem studies of patients with PD consistently demonstrated robust microglial activation in the substantia nigra.[21,30]

More interestingly, frequent use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, particularly ibuprofen, is associated with a lower risk of developing PD which could serve as an indirect evidence to support the role of chronic inflammation in the pathogenesis of this disease.[31]

The major strength of this study is the advantage of systemic review and meta-analysis that allows a comprehensive estimation of the risk. The results were robust as demonstrated by the sensitivity analysis. The major limitation is related to the methodology of the primary studies as those studies were conducted using coding-based medical registry which would raise a concern over misclassification and coding incompleteness. Moreover, because of the observational nature of the primary studies, this meta-analysis could only demonstrate an association but could not establish causality.

Conclusion

Our meta-analysis demonstrated a significantly increased risk of PD among patients with psoriasis. How this risk should be addressed in clinical practice needs further investigations.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

Patients with psoriasis are at a higher risk of Parkinson's disease with 38% excess risk compared with subjects without psoriasis.

References

- 1.Zheng KS, Dorfman BJ, Christos PJ, Khadem NR, Henchcliffe C, Piboolnurak P, et al. Clinical characteristics of exacerbations in Parkinson disease. Neurologist. 2012;18:120–4. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e318251e6f2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Lau LM, Breteler MM. Epidemiology of Parkinson's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:525–35. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70471-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pringsheim T, Jette N, Frolkis A, Steeves TD. The prevalence of Parkinson's disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov Disord. 2014;29:1583–90. doi: 10.1002/mds.25945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yan MH, Wang X, Zhu X. Mitochondrial defects and oxidative stress in Alzheimer disease and Parkinson disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;62:90–101. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henchcliffe C, Beal MF. Mitochondrial biology and oxidative stress in Parkinson disease pathogenesis. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2008;4:600–9. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wallin K, Solomon A, Kåreholt I, Tuomilehto J, Soininen H, Kivipelto M. Midlife rheumatoid arthritis increases the risk of cognitive impairment two decades later: A population-based study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;31:669–76. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-111736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu K, Wang HK, Yeh CC, Huang CY, Sung PS, Wang LC, et al. Association between autoimmune rheumatic diseases and the risk of dementia. Biomed Res Int 2014. 2014:861812. doi: 10.1155/2014/861812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dregan A, Chowienczyk P, Gulliford MC. Are inflammation and related therapy associated with all-cause dementia in a primary care population? J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;46:1039–47. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christophers E. Psoriasis – Epidemiology and clinical spectrum. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:314–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2001.00832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kokpol C, Aekplakorn W, Rajatanavin N. Prevalence and characteristics of metabolic syndrome in South-East Asian psoriatic patients: A case-control study. J Dermatol. 2014;41:898–902. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ungprasert P, Sanguankeo A, Upala S, Suksaranjit P. Psoriasis and risk of venous thromboembolism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. QJM. 2014;107:793–7. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcu073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ungprasert P, Srivali N, Thongprayoon C. Association between psoriasis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015:1–6. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2015.1107180. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maradit-Kremers H, Nicola PJ, Crowson CS, Ballman KV, Gabriel SE. Cardiovascular death in rheumatoid arthritis: A population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:722–32. doi: 10.1002/art.20878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ungprasert P, Charoenpong P, Ratanasrimetha P, Thongprayoon C, Cheungpasitporn W, Suksaranjit P. Risk of coronary artery disease in patients with systemic sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33:1099–104. doi: 10.1007/s10067-014-2681-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ungprasert P, Suksaranjit P, Spanuchart I, Leeaphorn N, Permpalung N. Risk of coronary artery disease in patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;44:63–7. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–5. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rugbjerg K, Friis S, Ritz B, Schernhammer ES, Korbo L, Olsen JH. Autoimmune disease and risk for Parkinson disease: A population-based case-control study. Neurology. 2009;73:1462–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c06635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li X, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Subsequent risks of Parkinson disease in patients with autoimmune and related disorders: A nationwide epidemiological study from Sweden. Neurodegener Dis. 2012;10:277–84. doi: 10.1159/000333222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sheu JJ, Wang KH, Lin HC, Huang CC. Psoriasis is associated with an increased risk of parkinsonism: A population-based 5-year follow-up study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:992–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.12.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chung J, Takeshita J, Shin DB, Haynes K, Arnold SE, Gelfand J. The Risk of Parkinson's Disease in Patients with Psoriasis: A Population-based Cohort Study. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology, Atlanta, GA; 6-9. 2015 May [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu G, Jousilahti P, Nissinen A, Antikainen R, Kivipelto M, Tuomilehto J. Body mass index and the risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2006;67:1955–9. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000247052.18422.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Correia B, Torres T. Obesity: A key component of psoriasis. Acta Biomed. 2015;86:121–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Armstrong EJ. The association between psoriasis and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Diabetes. 2012;2:e54. doi: 10.1038/nutd.2012.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ettehadi P, Greaves MW, Wallach D, Aderka D, Camp RD. Elevated tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) biological activity in psoriatic skin lesions. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994;96:146–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hunot S, Dugas N, Faucheux B, Hartmann A, Tardieu M, Debré P, et al. FcepsilonRII/CD23 is expressed in Parkinson's disease and induces, in vitro, production of nitric oxide and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in glial cells. J Neurosci. 1999;19:3440–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-09-03440.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beal MF. Experimental models of Parkinson's disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:325–34. doi: 10.1038/35072550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lawson LJ, Perry VH, Dri P, Gordon S. Heterogeneity in the distribution and morphology of microglia in the normal adult mouse brain. Neuroscience. 1990;39:151–70. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90229-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cicchetti F, Brownell AL, Williams K, Chen YI, Livni E, Isacson O. Neuroinflammation of the nigrostriatal pathway during progressive 6-OHDA dopamine degeneration in rats monitored by immunohistochemistry and PET imaging. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;15:991–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.01938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gagne JJ, Power MC. Anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of Parkinson disease: A meta-analysis. Neurology. 2010;74:995–1002. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d5a4a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.