Abstract

Infantile hemangiomas are a group of vascular tumors and are considered to be one of the most common tumors in infancy. Ambiguity still prevails over its origin, etiopathogenesis, and optimal management.

Keywords: Hemangiomas, infantile, propranolol

What was known?

Infantile hemangioma (IH) is the most common vascular tumor in childhood

Propranolol has emerged as the first line of medical intervention in the management of IHs.

Introduction

Vascular anomalies have been classified as vascular tumors and malformations, a modification to the original classification system by Finn et al. in 1982,[1] by the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies in 1996.[2] Infantile hemangioma (IH), grouped under vascular tumors, has a prevalence of 1.1–2.6% in term neonates as evidenced from the world literature and a 0.1–0.28% as recorded in Indian literature.[3] It derives its name from a Latin word “Hemangioma fructosum.” Although considered to be the most common tumor in infancy, ambiguity still prevails over its origin, etiopathogenesis, and optimal management.

Etiopathogenesis

IH pathogenesis is considered to be a complex interaction of both genetic and environmental factors. A closer look at clinical characteristics, including the marked clinical heterogeneity, the significance of premonitory marks, growth and involution characteristics, anatomic patterns, presence only in certain tissues, multifocal hemangiomas, and associated structural anomalies may all provide clues to the pathogenesis of IH.[4] Over the last decade, several theories have been proposed, of which Folkman Klagsbrun placental theory, endothelial progenitor cell theory, hypoxia theory, and angiogenesis theory are the most accepted.[5,6,7,8,9]

Clinical features

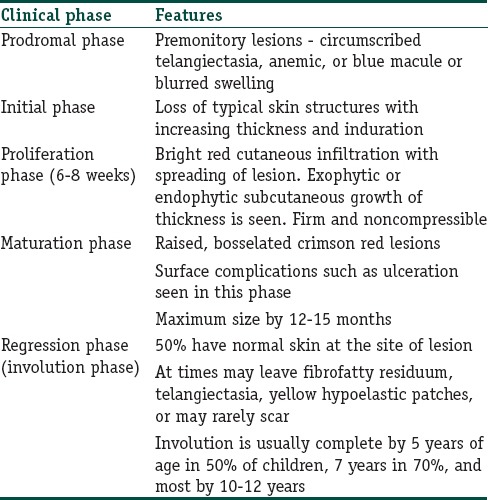

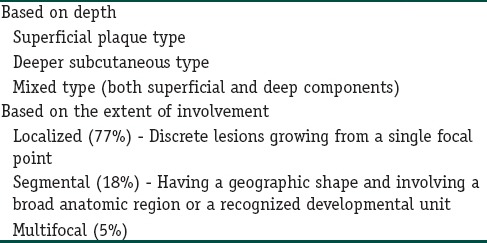

The risk factors and higher incidence of the development of IH are prematurity, multiple gestation, elderly primigravida, and placental abnormalities such as placenta previa and preeclampsia. It is more common in white infants (10%), with a higher female preponderance (3:1). The natural history of IH can be studied based on the clinical stage of the condition [Table 1].[9,10] These features help to differentiate it from its closest differential diagnosis of congenital hemangiomas, which are fully developed at birth with no postnatal growth. IH can be classified based on its depth and extent of involvement [Table 2].[4,10]

Table 1.

Phases of development of infantile hemangioma and correlation and clinical features

Table 2.

Classifications of infantile hemangioma

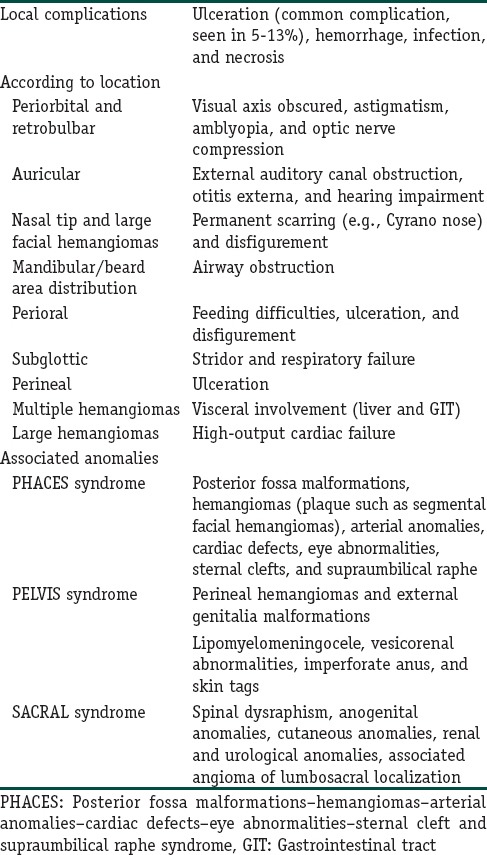

Complications of infantile hemangiomas

Morbidity and mortality resulting from IH are varied, ranging from life-threatening complications such as bleeding, airway obstruction mainly occurring during the proliferative phase to scarring and disfigurement seen predominantly in the involution phase. Various complications encountered in clinical practice have been discussed in Table 3.[8,9,10,11,12,13]

Table 3.

Complications of infantile hemangioma

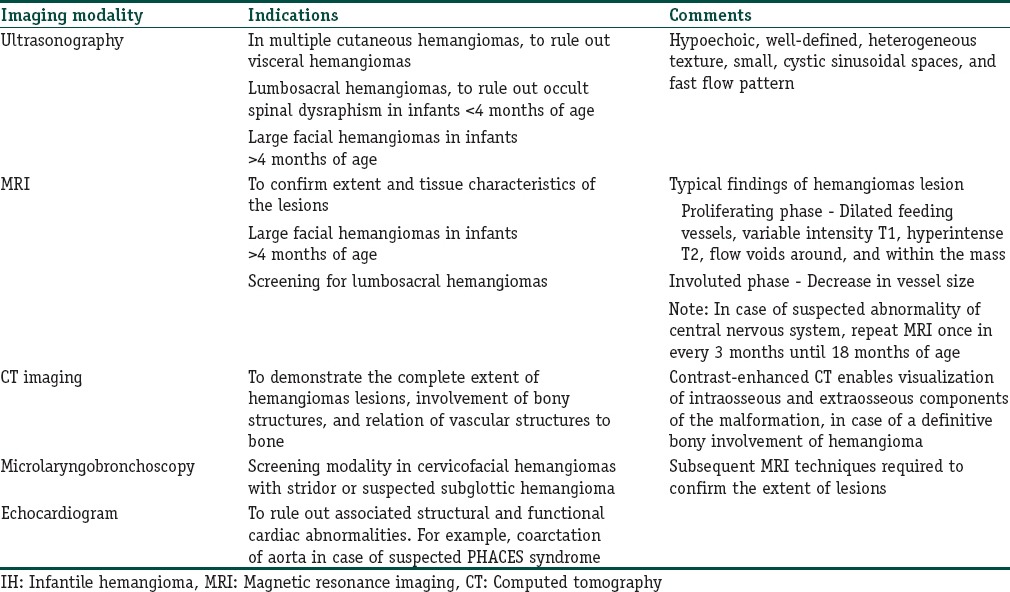

Diagnosis

IH is usually diagnosed based on history and examination. Investigations are deemed appropriate in case of doubtful cases (e.g., to differentiate deep IH and vascular malformations) or in case of suspected associated systemic abnormalities (e.g., large facial segmental plaque-like hemangiomas can be associated with posterior fossa malformations–hemangiomas–arterial anomalies–cardiac defects–eye abnormalities–sternal cleft and supraumbilical raphe [PHACES] syndrome).[12]

Line of work up for large facial hemangiomas includes an ultrasound (US) of the head in infants <4 months of age and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with angiography for those >4 months of age. In case of detected central nervous system abnormalities, a repeat MRI once every 3 months until 18 months of age is recommended. USG of an IH lesion can help rule out a close differential diagnosis of vascular malformations. Characteristic findings in US include well-defined hypoechoic, heterogeneous texture with cystic sinusoidal spaces, and fast flow pattern. Further, infants with >5 IH lesions warrant a hepatic US considering the possibility of hepatic hemangiomas. Minority of these can be multifocal liver hemangiomas, which can result in high output cardiac failure. A rarer form, diffuse hepatic hemangiomas can cause abdominal compartment syndrome and a severe form of hypothyroidism.[13] MRI can be used to confirm the extent and tissue characteristics of IH lesions. Typical features in the proliferating phase include dilated feeding vessels, variable intensity T1, hyperintense T2, and flow voids around and within the mass. In the involuted phase, decrease in vessel size is seen.[14] The various imaging modalities in special situations have been described briefly in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of imaging modalities in infantile hemangioma

Biopsy can be considered in case of lesions with unclear etiology, unusual appearances, and atypical features. Early proliferating lesions display solid cellular lobules composed of plump endothelial cells lining tiny rounded vascular spaces with inconspicuous lumina.[12] Regressed lesions show progressive fibrosis, absent vascular elements, and fat replacement of vascular tissue in the subcutaneous layer. The expression of glucose transporters-1 only in IH endothelium helps confirm the diagnosis.

Recently, urinary basic fibroblast growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor estimation have been found to be reliable markers in IH proliferation and differentiation.[13]

Treatment

The “Guidelines of care for hemangiomas of infancy” published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology,[14] defines the major goals of the management of IH as:

Prevention or reversal of life-threatening or function-threatening complications

Prevention of permanent disfigurement, diminution of psychosocial stress for the patient and family

Avoidance of aggressive or detrimental interventions in lesions that may have excellent prognosis without treatment

Prevention or treatment of ulceration to lower scarring, infection, and pain.

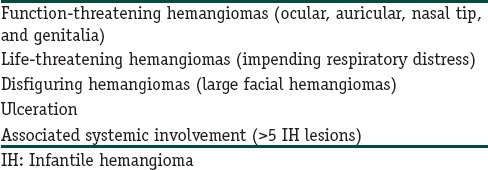

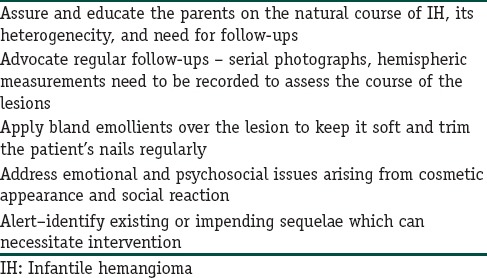

Most cases of IH are self-limited and require no active intervention. The indication for treatment and how best to administer the same depends on the clinical situation and must take into consideration the factors such as age of the patient, location of lesions, complications, and risks for the same, and growth rate of the lesions [Table 5].[9,13,14] An “active nonintervention” approach suffices in most cases of uncomplicated IH [Table 6].[13,14]

Table 5.

Indications for medical intervention in infantile hemangioma

Table 6.

Components of active nonintervention

A Cochrane analysis of interventions for IH noted that a lack of well-designed clinical trials and the absence of US Food and Drug Administration-approved medications for IH limits the ability to clearly identify a single best treatment option for IHs.[15]

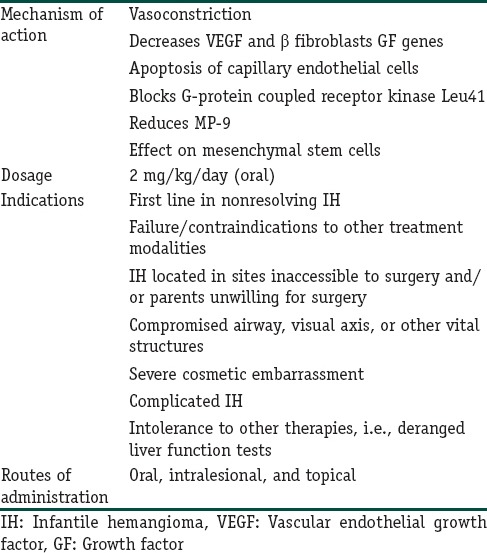

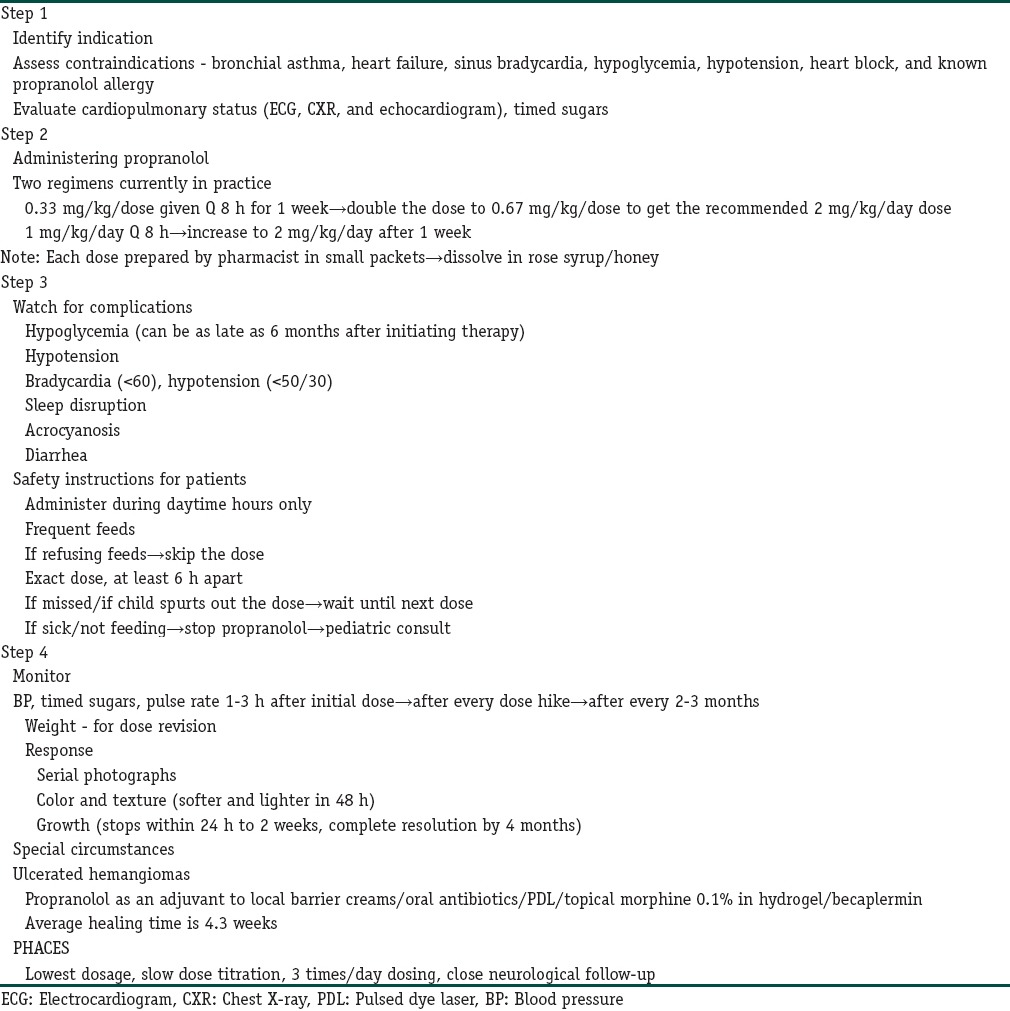

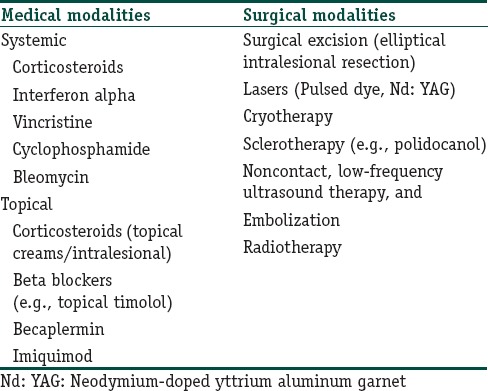

Until recently, systemic and intralesional corticosteroids were the mainstay of management of complicated hemangiomas. However, at present, beta-blockers, in particular, propranolol has come up as the first line of management of IH [Tables 7 and 8].[4,16,17,18,19] Various other modalities can be tried in clinical practice for managing IH [Table 9].[18,19,20,21,22,23,24]

Table 7.

Propranolol - mechanism of action, indications, dosage, and routes of administration

Table 8.

An algorithm to manage infantile hemangioma with oral propranolol

Table 9.

Therapeutic modalities for the management of infantile hemangioma

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

Use of propranolol has been gaining popularity as dermatologists are more aware of the monitoring and dosing methodology

Management of IH varies from patient to patient. Adequate knowledge on various treatment modalities is crucial for the same.

References

- 1.Finn MC, Glowacki J, Mulliken JB. Congenital vascular lesions: Clinical application of a new classification. J Pediatr Surg. 1983;18:894–900. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(83)80043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Enjolras O, Mulliken JB. Vascular tumors and vascular malformations (new issues) Adv Dermatol. 1997;13:375–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mendiratta V, Jabeen M. Infantile hemangioma: An update. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:469–75. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.69048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frieden IJ, Haggstrom AN, Drolet BA, Mancini AJ, Friedlander SF, Boon L, et al. Infantile hemangiomas: Current knowledge, future directions. Proceedings of a research workshop on infantile hemangiomas, April 7-9, 2005, Bethesda, Maryland, USA. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:383–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2005.00102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen TS, Eichenfield LF, Friedlander SF. Infantile hemangiomas: An update on pathogenesis and therapy. Pediatrics. 2013;131:99–108. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.North PE, Waner M, Mizeracki A, Mihm MC., Jr GLUT1: A newly discovered immunohistochemical marker for juvenile hemangiomas. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:11–22. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(00)80192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drolet BA, Frieden IJ. Characteristics of infantile hemangiomas as clues to pathogenesis: Does hypoxia connect the dots? Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1295–9. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holland KE, Drolet BA. Approach to the patient with an infantile hemangioma. Dermatol Clin. 2013;31:289–301. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hajheydari Z, Shahmohammadi S, Talaee R. Update on infantile haemangioma. J Pediatr Rev. 2014;2:29–38. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong A, Wu JK. Sophia Ran Dr., editor. Infantile Hemangiomas: A Disease Model in the Study of Vascular Development, Aberrant Vasculogenesis and Angiogenesis, Tumor Angiogenesis. [Last accessed on 2015 Feb 24]. ISBN: 978-953-51-0009-62012 InTech. Available from: http://www.intechopen.com/books/tumor-angiogenesis/infantilehemangiomas-a-disease-model-in-the-study-of-vascular-development-aberrant-vasculogenesis-a .

- 11.Bowers RE, Graham EA, Tomlinson KM. The natural history of the strawberry nevus. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:667–80. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Callahan AB, Yoon MK. Infantile hemangiomas: A review. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2012;26:283–91. doi: 10.1016/j.sjopt.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang L, Lin X, Wang W, Zhuang X, Dong J, Qi Z, et al. Circulating level of vascular endothelial growth factor in differentiating hemangioma from vascular malformation patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:200–4. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000170804.80834.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frieden IJ, Eichenfield LF, Esterly NB, Geronemus R, Mallory SB. Guidelines of care for hemangiomas of infancy. American Academy of Dermatology Guidelines/Outcomes Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:631–7. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70183-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haggstrom AN, Drolet BA, Baselga E, Chamlin SL, Garzon MC, Horii KA, et al. Prospective study of infantile hemangiomas: Clinical characteristics predicting complications and treatment. Pediatrics. 2006;118:882–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kum JJ, Khan ZA. Propranolol inhibits growth of hemangioma-initiating cells but does not induce apoptosis. Pediatr Res. 2014;75:381–8. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sethuraman G, Yenamandra VK, Gupta V. Management of infantile hemangiomas: Current trends. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2014;7:75–85. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.138324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greinwald JH, Jr, Burke DK, Bonthius DJ, Bauman NM, Smith RJ. An update on the treatment of hemangiomas in children with interferon alfa-2a. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;125:21–7. doi: 10.1001/archotol.125.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gunturi N, Ramgopal S, Balagopal S, Scott JX. Propranolol therapy for infantile hemangioma. Indian Pediatr. 2013;50:307–13. doi: 10.1007/s13312-013-0098-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chowdri NA, Darzi MA, Fazili Z, Iqbal S. Intralesional corticosteroid therapy for childhood cutaneous hemangiomas. Ann Plast Surg. 1994;33:46–51. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199407000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poetke M, Philipp C, Berlien HP. Flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser for hemangiomas in infancy: Treatment of superficial vs mixed hemangiomas. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:628–32. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.5.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grover C, Khurana A, Bhattacharya SN. Sclerotherapy for the treatment of infantile hemangiomas. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2012;5:201–3. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.101383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mascarenhas R, Guiote V, Agro J, Henrique M. Ulcerated infantile hemangioma treated with imiquimod. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nomura T, Osaki T, Ishinagi H, Ejiri H, Terashi H. Simple and easy surgical technique for infantile hemangiomas: Intralesional excision and primary closure. Eplasty. 2015;15:e3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]