Abstract

Amyloidosis is a group of heterogeneous diseases characterized by pathological deposition of proteinaceous substance extracellularly in various tissues. The clinical presentation depends on the site of amyloid deposition, with predominant involvement of mesenchymal elements and cutaneous findings in 30–40% of patients in case of primary systemic amyloidosis. We present a case of idiopathic primary systemic amyloidosis presenting with an unusual finding of nodulo-ulcerative lesion over tongue along with multiple skin-colored nodules, mimicking squamous cell carcinoma of tongue with secondary cutaneous metastasis, as well as lacking the classical presentation of purpura, macroglossia, waxy papules, and plaques.

Keywords: Amyloidosis, nodules, purpura

What was known?

All forms of systemic amyloidosis are of rare occurrence. Classical cutaneous lesions are petechiae, purpura, ecchymosis, waxy and translucent papules and plaques.

Introduction

Amyloidosis is the disease caused by the extracellular deposition of insoluble polymeric protein fibrils in tissues and organs.[1] Skin involvement can occur as primary cutaneous amyloidosis or as a part of systemic amyloidosis. In localized cutaneous disease, the amyloidogenic protein is produced at the site of deposition. In contrast, amyloidogenic protein is produced at a site that is distant from the site of deposition in case of systemic disease. Systemic amyloidosis can be classified as primary, secondary, or familial. Primary systemic amyloidosis (also known as amyloid light-chain [AL] amyloidosis) arises from clonal B-cell disorder and may be associated with multiple myeloma, lymphoma, or can even be idiopathic.[2] The most common skin lesions in primary systemic amyloidosis, i.e., petechiae, purpura, and ecchymosis, are those related to intracutaneous hemorrhage due to infiltration of blood vessel wall by amyloid. We present a case of extensive cutaneous involvement in nonmyeloma primary systemic amyloidosis, lacking the classical presentation of purpura, macroglossia, waxy papules, and plaques, but presenting with multiple skin-colored nodules all over the body and a noduloulcerative growth on the tongue, mimicking squamous cell carcinoma with secondary cutaneous metastasis.

Case Report

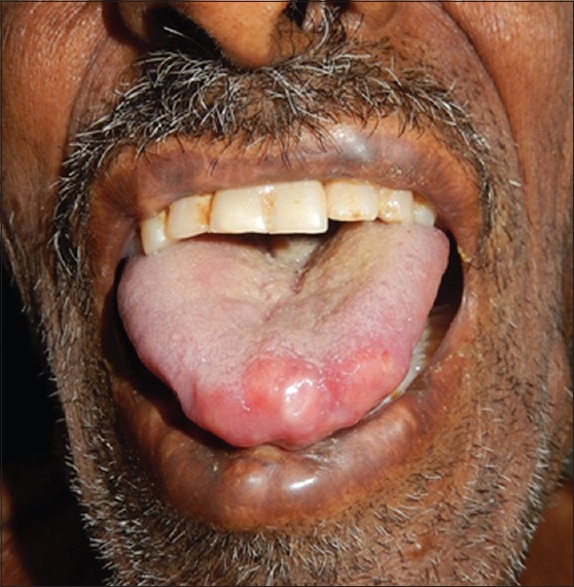

A 75-year-old debilitated man presented with multiple asymptomatic nodular lesions all over body since 8 months and difficulty in swallowing for the past 6 months. He also presented history of fatigue, progressive weight loss, and breathlessness. General examination revealed pallor and cervical lymphadenopathy. Lymph nodes were nontender, firm, discrete, of size 1.5–2 cm, and not fixed to the underlying structures. On cutaneous examination, there were multiple skin-colored, firm to hard, nontender nodules of size ranging from 2 to 5 cm over scalp and trunk, with few scattered lesions over extremities [Figure 1]. Multiple nodules coalescing to form plaques in the convoluted pattern were present on the occipital region, resembling cutis verticis gyrata. A 3 cm × 3 cm noduloulcerative growth on the left lateral border and tip of the tongue was seen on mucosal examination. A few nontender firm nodules were also present on lips [Figure 2]. Hair and nail examination was normal. Systemic examination was not contributory. Clinical impression was that of squamous cell carcinoma of tongue with secondary cutaneous metastasis.

Figure 1.

(a) Cutis verticis gyrata-like appearance of scalp, (b) multiple skin-colored nodules over back

Figure 2.

Nodulo-ulcerative lesion on tip and left lateral border of the tongue, also showing a few nodules on lips

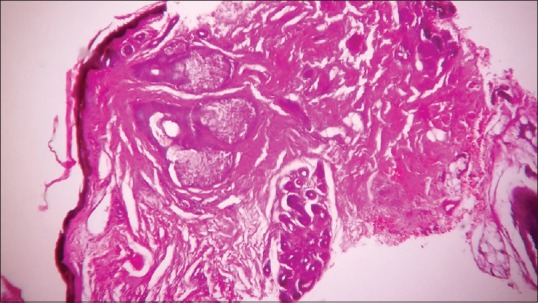

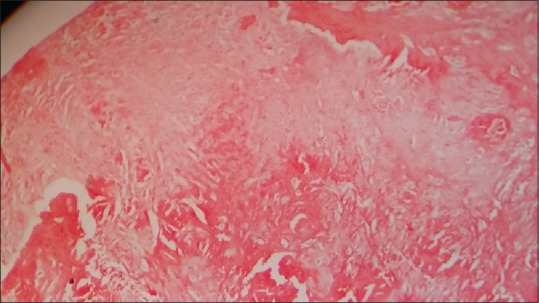

Routine laboratory investigations including complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, liver and kidney function tests, chest X-ray, and electrocardiogram were normal except anemia (hemoglobin = 6). There was presence of granular and waxy casts with 2+ albuminuria on urine examination. Skin biopsy was taken from lesion over back and tongue. The presence of eosinophilic acellular homogenous material in the dermis and Peri-adnexal region was noted in both the biopsies [Figure 3]. Congo red staining done due to suspected amyloid deposition was positive [Figure 4].

Figure 3.

Eosinophilic homogenous material in the dermis and peri-adnexal region (H and E, ×400)

Figure 4.

Congo red positivity (×400)

In an effort to look for plasma cell dyscrasia, relevant investigations were carried out. Serum and urine electrophoresis failed to reveal M-spike. Serum calcium was within normal limits. Radiological survey (high-resolution computed tomography head, thorax, and abdomen), and echocardiography was normal. Bone marrow biopsy was normal, with plasma cells <15%. Ultrasound abdomen showed scattered hyperechoic shadows in bilateral kidney and mild hepatomegaly. Abdominal fat aspiration for amyloid was negative. Rectal biopsy could not be performed as the patient did not give consent.

Diagnosis of idiopathic primary systemic amyloidosis was made based on clinical features and investigations that satisfactorily ruled out the association with multiple myeloma.

Discussion

The term “amyloid” was first used in 1853 by pathologist Rudolf Virchow.[3] Amyloidosis encompasses a heterogeneous group of misfolded protein disorders, where the misfolding, due to some unknown reasons, leads to aggregation and deposition of highly insoluble protein fibrils having beta-pleated sheet configuration, known as amyloid. Among 25 different proteins identified to produce amyloid fibrils, most are constituents of plasma.[4]

Primary systemic amyloidosis (AL amyloidosis) is usually associated with plasma cell dyscrasia, but in some cases obvious B-cell/plasma cell neoplasm cannot be identified, hence the term “idiopathic”.[5] It is the amyloidosis composed of immunoglobulin light chains. In secondary systemic amyloidosis, skin involvement occurs very rarely.[1]

AL amyloidosis generally presents in late age. These patients might have underlying B-cell dyscrasia in which production of abnormal protein, rather than production of tumor masses, is the only clinically apparent manifestation. Cutaneous involvement, seen in 40% cases, depends on the site of amyloid deposited.[5] Common cutaneous lesions are petechiae, purpura, ecchymosis, waxy and translucent papules, plaques and tumefactive lesions, all lacking in the index case. In addition, the classical triad of carpal tunnel syndrome, macroglossia, and specific mucocutaneous lesions, seen in half of the patients, is absent. Instead of macroglossia or diffuse papular lesions on tongue, there is a localized nodulo-ulcerative lesion, and mimicking squamous cell carcinoma.

Herein, hematoxylin, and eosin followed by Congo red staining confirmed the diagnosis. In this case, the amyloid deposits up to the deep dermis resulted in nodular lesions. Bone marrow biopsy is done to find out plasma cell dyscrasias. Subcutaneous abdominal fat aspiration is the preferred method for detecting systemic amyloidosis. The negative result in our case might be attributed to insufficient amount of sample or faulty technique. Unfortunately, rectal biopsy, which is the gold standard technique for diagnosis of systemic amyloidosis, could not be performed. Clinically, it is difficult to distinguish primary, secondary, or familial form of amyloidosis. Despite the different chemical composition and myriad clinical presentation, all amyloid share three common features – amorphous eosinophilic appearance on hematoxylin and eosin stain, classical green birefringence on congo red stain under polarized light, and beta-pleated structure on X-ray crystallography. However, when available, immunohistochemical staining must be done to classify the type of amyloid protein.

All forms of systemic amyloidosis are of rare occurrence. The case presented here has unusual dermatological manifestations of amyloidosis. Instead of diffuse enlargement of tongue (macroglossia), there is a localized lesion that mimics squamous cell carcinoma, thus posing diagnostic dilemma. This emphasizes the importance of suspecting amyloidosis despite the absence of classical cutaneous findings. Plasma cell dyscrasia is the underlying cause; nevertheless, in some cases it is not possible to demonstrate a paraprotein,[6] as noted in the index case as well.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

Rarely, systemic amyloidosis can present as localized nodulo-ulcerative lesion over tongue, clinically simulating squamous cell carcinoma.

References

- 1.Breathnach SM. Metabolic and nutritional disorders. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 7th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2004. pp. 57.36–57.51. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar S, Sengupta RS, Kakkar N, Sharma A, Singh S, Varma S. Skin involvement in primary systemic amyloidosis. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2013;5:e2013005. doi: 10.4084/MJHID.2013.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seldin DC, Skinner M. Amyloidosis. In: Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, editors. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. USA: McGraw-Hill Companies; 2012. pp. 945–50. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chattopadhyay A, Dutta S, Majumder A, Das J. Primary systemic amyloidosis presenting at an early age: A case report. Int J Case Rep Images. 2014;5:99–103. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saoji V, Chaudhari S, Gohokar D. Primary systemic amyloidosis: Three different presentations. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:394–7. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.53138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crow KD. Primary amyloidosis. Br J Dermatol. 1977;97(Suppl 15):58–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1977.tb14332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]