Abstract

The deep-sea is the largest biome of the biosphere, and contains more than half of the whole ocean's microbes. Uncovering their general patterns of diversity and community structure at a global scale remains a great challenge, as only fragmentary information of deep-sea microbial diversity exists based on regional-scale studies. Here we report the first globally comprehensive survey of the prokaryotic communities inhabiting the bathypelagic ocean using high-throughput sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene. This work identifies the dominant prokaryotes in the pelagic deep ocean and reveals that 50% of the operational taxonomic units (OTUs) belong to previously unknown prokaryotic taxa, most of which are rare and appear in just a few samples. We show that whereas the local richness of communities is comparable to that observed in previous regional studies, the global pool of prokaryotic taxa detected is modest (~3600 OTUs), as a high proportion of OTUs are shared among samples. The water masses appear to act as clear drivers of the geographical distribution of both particle-attached and free-living prokaryotes. In addition, we show that the deep-oceanic basins in which the bathypelagic realm is divided contain different particle-attached (but not free-living) microbial communities. The combination of the aging of the water masses and a lack of complete dispersal are identified as the main drivers for this biogeographical pattern. All together, we identify the potential of the deep ocean as a reservoir of still unknown biological diversity with a higher degree of spatial complexity than hitherto considered.

Introduction

The pelagic dark ocean (the water column >200 m deep) contains 70% of the ocean's microbial cells and 60% of its heterotrophic activity, with a pivotal regulatory role in planetary biogeochemical cycles (Arístegui et al., 2009). Yet, current knowledge of the pelagic microbial community structure of the dark ocean, the largest biome in the biosphere, is based on a pool of samples collected at specific locations (DeLong et al., 2006; Martín-Cuadrado et al., 2007; Brown et al., 2009; Galand et al., 2010; Agogué et al., 2011; Eloe et al., 2011; Quaiser et al., 2011; Smedile et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2013; Wilkins et al., 2013; Ganesh et al., 2014) (Supplementary Figure S1) and thus are dwarf in comparison with the analyses of upper ocean microbial communities, which have indeed been assessed at global scales (Rusch et al., 2007; Yooseph et al., 2007; Zinger et al., 2011; Sunagawa et al., 2015). Whereas the deep ocean is often considered to be a rather uniform environment, the connectivity of pelagic microbial communities may be reduced by the limited mixing between water masses (Agogué et al., 2011; Hamdan et al., 2013) or modulated by advection (Wilkins et al., 2013) imposing limitations on the dispersion of marine microbes in this low-turbulence environment. In addition, the spatial structure of the bathypelagic ocean, organized in partially isolated basins created by the emergence of submarine mountains, has not been tested as a potential factor affecting the biogeography of pelagic microbial communities, as happens for specialized deep-sea fauna (Moalic et al., 2012) and bacteria inhabiting deep-sea surface sediments (Schauer et al., 2010), either by imposing limits to deep-ocean connectivity or by delineating different environments that select for distinct microbial communities. Therefore, the deep pelagic ocean may present a mosaic of biogeographical domains with distinct microbial assemblages, a hypothesis not yet fully tested.

We created a global collection of samples retrieved during the Malaspina 2010 circumnavigation expedition (cf. Irigoien et al., 2014) and we have used high-throughput sequencing of the 16S rRNA genes jointly with automated ribosomal intergenic spacer analysis (ARISA) profiles and metagenomic data of the prokaryotes present in bathypelagic waters of the main world's oceans to describe their diversity, community structure and biogeographical distribution and identify the cosmopolitan and/or abundant prokaryotes in the dark ocean at a global scale. Moreover, we aimed to test whether deep-sea pelagic prokaryotic communities are uniform or present biogeographical patterns delineated by water mass and/or deep-oceanic basins.

Material and methods

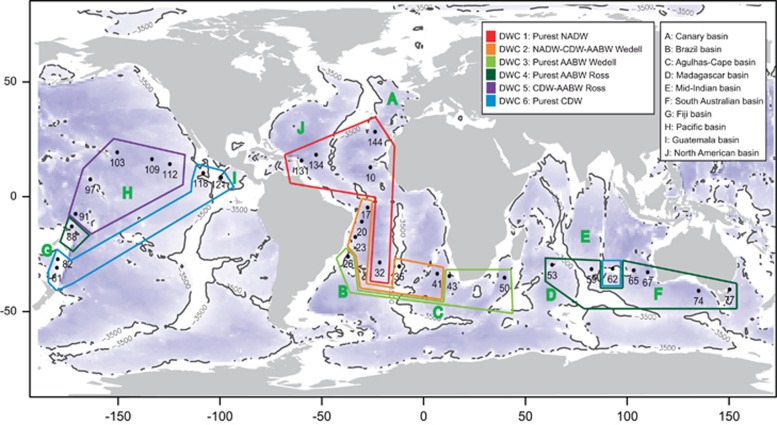

A total of 60 water samples were taken during the Malaspina 2010 expedition (http://scientific.expedicionmalaspina.es/) corresponding to 30 different sampling stations globally distributed across the world's oceans (Figure 1). We focused on the samples at the depth of 4000 m, although a few samples were taken at lower depths, all well within the bathypelagic realm.

Figure 1.

World map showing the location of the Malaspina sampling stations in the present study. The deep-water cluster derived from dominant water masses found at each station are color-coded, and the deep-oceanic basins defined according to bathymetry below 3500 m depth (see Materials and methods for details) are indicated with letters.

Sample collection and processing

Two different size fractions were analyzed in each station representing the free-living (0.2–0.8 μm) and particle-attached (0.8–20 μm) prokaryotic communities (Crump et al., 1999; Ghiglione et al., 2009; Allen et al., 2012). For each sample 120 l of sea water were sequentially filtered through a 200 and a 20 μm mesh to remove large plankton. Further filtering was done by pumping water serially through 142-mm polycarbonate membrane filters of 0.8 μm (Merk Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany, Isopore polycarbonate) and 0.2 μm (Merck Millipore, Express Plus) pore size with a peristaltic pump (Masterflex, EW-77410-10). The filters were then flash-frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80 °C until DNA extraction. The time span from bottle closing to filter freezing was ~4 h and except for the time needed to empty the rosette bottles, the water was kept at 4 °C. DNA extractions were performed using the standard phenol–chloroform protocol (see Supplementary Information), and prokaryotic diversity was assessed by amplicon sequencing of the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene with the Illumina MiSeq platform (iTags) using paired-end reads (2 × 250 bp) and primers F515/R806 (details in Supplementary Information) targeting both Archaea and Bacteria (Caporaso et al., 2011). Sequence data processing included the paired-end reads assembly, end-trimming, sequence quality control and chimera checking process integrated in the Joint Genome Intitute pipeline. Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were obtained by clustering the processed data at a 97% identity and the taxonomic annotation of consensus sequences was performed using the SILVA v111 database (details in Supplementary Information). ARISA and metagenomic data analyses were also applied to the same samples as an independent validation of the iTag approach (see Supplementary Information).

Statistical data analyses

Statistical analyses (see details below) included richness estimation and rarefaction curves. The analysis of differences in community composition among samples and their relation to potential drivers assessed by means of a combination of multivariate exploratory techniques based on Bray–Curtis similarities (non-metric multidimensional scaling) and hypothesis testing methods (permutational multivariate analysis of variance). The novelty of the obtained 16S rRNA gene sequences was checked against the SILVA, NCBI and RDP public databases using BLAST. All the sequences used in this study are publicly available at the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/sra) under accession ID SRP031469. All statistical analyses and data treatment were conducted with the R Statistical Software (R Core Team, 2014) using version 3.0.1 and the following packages: BiodiversityR, ecodist, gdistance, marelac and vegan. The iTags were used as the primary data set for the whole study. ARISA and metagenomic data were used in specific analyses to compare with the iTag-derived data.

Novelty of the deep-ocean 16S rRNA gene sequences

To evaluate the novelty of the obtained 16S rRNA gene sequences, the 3507 representative OTU sequences were compared with RDP (Cole et al., 2014), SILVA v111 (Pruesse et al., 2007) and NCBI RefSeq (Pruitt et al., 2012) public databases. The nucleotide subsets of the databases were downloaded (January 2013) and served as reference for a BLAST (Altschul et al., 1990) comparison. A cutoff e-value of 1E-05 was used, a maximum of five target sequences were allowed for each query sequence and only the matches with coverage >90% were considered. When more than one match existed with an acceptable coverage and e-value, the one with the highest identity was chosen and identity values to the closest match for each sequence were collected.

Beta-diversity patterns of prokaryotic community composition

To infer the variation of the prokaryotic assemblages in space and along environmental gradients (that is, beta-diversity), the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity index was used on community composition. The OTU-abundance table obtained from the sequence clustering was sampled down to the lowest sampling effort (10 617 reads per sample), and dissimilarities between all pairs of samples were calculated using Bray–Curtis dissimilarity coefficient to obtain a beta-diversity matrix. The resulting dissimilarity matrix was used to perform an non-metric multidimensional scaling (Minchin, 1987) analysis using random starts. Permutational multivariate analysis of variance using 1000 permutations was used to test for significant differences and to partition the beta-diversity matrix variance between groups of samples (Anderson, 2001; Anderson and Walsh, 2013).

The differential contribution (Di,b) of a specific basin to the total abundance of a specific OTU was computed for the 30 most abundant OTUs. This was calculated for each OTU and each basin following the formula:

where Xi,b is the contribution of the basin b to the total abundance of OTU i (that is, the number of reads of OTU i in the samples belonging to the basin b divided by the total number of reads of OTU i) and Nb is proportion of samples in the data set belonging to basin b. Thus, an OTU with a percentage of reads coming from a specific basin higher/lower than would be expected under an even distribution across samples would have a positive/negative Di,b value.

Processes shaping prokaryotic biogeography

To infer the relative importance of the processes shaping the biogeographical patterns, the relative contribution of environmental drivers and geographical distance to the beta-diversity of deep-ocean prokaryotic communities was assessed by means of a combined statistical strategy applied separately to both size fractions. First, the best subset of environmental drivers was selected using the BIOENV approach (Clarke and Ainsworth, 1993). Second, permutation-based multiple regression on matrices was used to partition the variance of the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity into (i) pure environmental variation, (ii) pure geographical variation, (iii) spatially structured environmental variation and (iv) and the unexplained variation (see details in Supplementary Information).

In addition, the scale of geographical variation was studied by means of Mantel correlograms (Oden and Sokal, 1986), which assesses the spatial correlation of multivariate data by computing a Mantel statistic (r) between the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity matrix and a matrix where pairs of sites belonging to the same geographic distance class receive value 0 and the other pairs, value 1. The process is repeated for each distance class and each r-value can be tested for significance by permutation. Distance classes of 1500 km were used. Mantel correlograms were run for each size-fraction separately.

Dominant phylum level analysis

To study the composition of prokaryotic communities at a broad taxonomic level a phylum-abundance table was derived from the OTU-abundance table by adding up all the OTUs belonging to the same phyla based on their SILVA taxonomy affiliation. For comparison with similar studies the phylum Proteobacteria was divided into its Classes. OTUs that could not be assigned to any phyla were included into an extra category (named as others). Only the phyla represented by >0.5% of the reads in the whole data set were considered. Differences in abundance for every Phylum between Oceans (categorized as North Atlantic, South Atlantic, Indian, South Pacific and North Pacific), deep-oceanic basins and ‘deep-water clusters'—see Supplementary Information—were statistically tested using multivariate analysis of variance. P-values were then Bonferroni-corrected for the effect of multiple comparisons.

Results and discussion

We examined pelagic prokaryotic diversity from two size fractions considered free-living and particle-attached (see Materials and methods), in 30 deep-ocean sites distributed in the North Atlantic (4 sites), South Atlantic (8), Indian (6) and South (5) and North Pacific Oceans (6), and an additional set of samples that was taken from the Southern Ocean in waters close to Australia (Figure 1). We targeted 4000 meters as the water depth of study taken as representative of the bathypelagic ocean, yet some samples were taken from shallower depths (always >2000 m). The sites were assigned to each of six different deep-water clusters according to their water mass composition (Supplementary Figure S2 and Supplementary Table S1), as well as to ‘deep-oceanic basins' based on the global ocean's bathymetry (Figure 1; details in Supplementary Information). Using Illumina sequencing of the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene, we obtained a final data set of 1 789 427 sequences (iTags) that could be constrained into a total of 3695 OTUs, which represents a minimum estimate of the richness of prokaryote taxonomic units in the deep-ocean (Supplementary Table S2). The iTag data was compared with ARISA-derived and metagenomic data revealing a good consistency between techniques (see Supplementary Information and Supplementary Figures S3 and S4). Hereafter, the downstream analyses were performed using iTags as the default data set.

Richness of bathypelagic prokaryotic communities

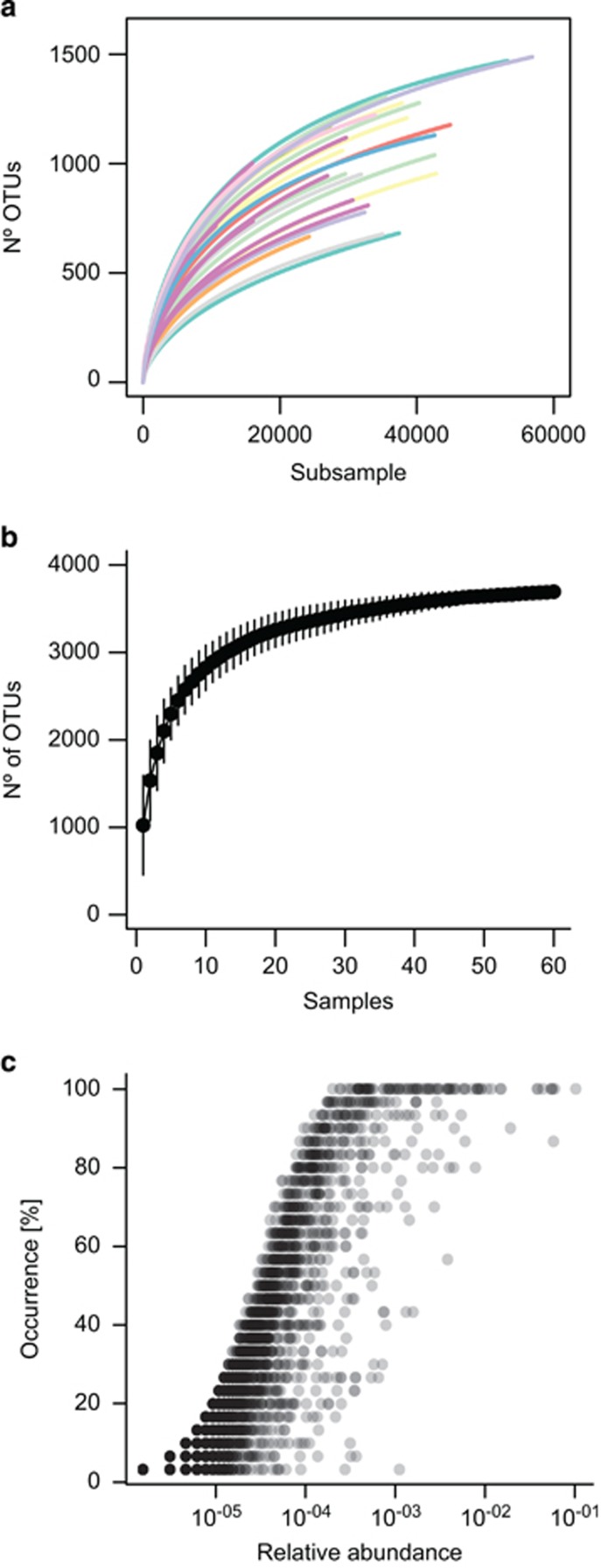

Two kinds of rarefaction curves were computed to check whether prokaryotic richness was close or far from saturation, both at the local (individual site/sample) and at the global (all samples) scale. For each sample, a rarefaction curve (or individual sample-based rarefaction curves) was drawn by sequentially computing the number of OTUs for an increasing number of reads. In addition, a sample-based rarefaction curve was drawn by randomly accumulating an increasing number of samples for the whole data set. Rarefaction curves for individual samples showed that prokaryotic diversity at the OTU level (97% identity cutoff) was far from saturation locally with the sequencing effort used (Figure 2a). In contrast, when considering the global set of samples, the sample-based rarefaction curves reached a considerably flat plateau at ~3500 OTUs (Figure 2b). The number of OTUs increased rapidly with the addition of the first 10 samples but once ~20 samples were considered, the addition of extra samples resulted in a small additional discovery of new OTUs. In fact, on average 42.0% of the OTUs present in one sample were shared with a second one taken at random from our data set (min=15.7%, max=76.2%), being these shared OTUs the ones with higher abundances (Figure 2c). This indicates that the global deep ocean contains a relatively modest number of prokaryotic phylotypes, likely in the order of a few thousands. The total number of OTUs identified here, 3695, represents, however, a minimum estimate, as strict data-cleaning criteria have been used in the data processing (specially, the removal of possible chimeric sequences and singletons) and as additional OTUs are likely to be present in areas not sampled in this study, such as the Arctic or Antarctica.

Figure 2.

Rarefaction curves. (a) within samples, individual-based and (b) sample-based. Global data set relative abundance vs occurrence (that is, the percentage of samples in which an OTU occurs) for all the OTUs (c). The sample-based rarefaction curve has been calculated for the entire data set. The deep-oceanic basins to which each station belongs are indicated with different colors in (a). (legend in Figure 5). No significant differences were detected for richness/diversity (neither OTU number, Chao1 nor Shannon index) between basins.

Each deep-sea prokaryotic community sampled here can be thus considered to be composed of (i) a set of dominant species shared with the rest of the stations in varying proportions, which we estimate at ~42 % of the OTUs identified and (ii) a set of low abundant and relatively sample-specific (that is, highly unshared) set of taxa comprising a ‘rare biosphere' (Sogin et al., 2006; Pedrós-Alió, 2012) of the global pool of deep-sea prokaryotes.

To prevent artifacts during diversity/richness estimations owing to uneven sampling efforts among samples, the data set was randomly sampled down to the lowest sequencing effort (10 617 reads per sample). This resulted in 637 020 reads corresponding to a total of 3543 OTUs. The number of OTUs in each community ranged from 248 to 896 (mean=659.1, s.d.=146.0), comparable to the mean local richness reported before in the Atlantic Ocean (mean=835, s.d.=421; Agogué et al., 2011). Slightly higher values (mean=1037.3, s.d.=173.6) had previously been reported in bathypelagic samples from polar and mid-latitudes (see samples below 1000 m from Supplementary Table 1 in Ghiglione et al., 2012). Thus, the global assessment of bathypelagic prokaryotic communities that we report delivers local richness values comparable to those observed in previous regional-scale bathypelagic surveys. However, our estimate of the total prokaryotic richness in the bathypelagic ocean estimated at ~3600 OTUs is consistent with previous estimates that found a total richness of 10 846 OTUs with half of them corresponding to singletons (Zinger et al., 2011). This represents a small fraction (~3% and 5.5%) of the total oceanic plankton bacterial richness found by recent surveys with comparable methodologies: a previous study combining 509 benthic and pelagic marine samples ranging from 0 to 5400 m depth found a total richness of ~120 000 OTUs (Zinger et al., 2011), whereas a total richness of ~65 500 OTUs was detected in a different study using data from 277 epipelagic samples (243 of which were also included in the previous one) from the Arctic, Atlantic, Pacific and Southern Oceans (Sul et al., 2013). This would suggest that only a small fraction of all oceanic microbes are found in the deep ocean.

Novelty of bathypelagic prokaryotic lineages

We assessed the degree of novelty of bathypelagic prokaryotic diversity by comparing the detected 16S rRNA gene sequences to those present in public databases. OTU representative sequences were compared with the RDP, SILVA and NCBI databases using 95% and 97/99% identity values as proxies for genus and ‘species' level, respectively. The three databases provided comparable identity distributions with two clear peaks, the first one at ~95% identity and a second peak near the 100% identity (Supplementary Figure S5). Interestingly, around one-third of the OTUs had identity values lower than 95%, half of the OTUs lower than 97% and 2/3 of the OTUs had values lower than 99%. Although the 97% identity is widely used in microbial ecology studies as a broad proxy for ‘species' cutoff (Stackebrandt and Goebel, 1994; Cohan, 2002; Hagström et al., 2002), it is well known that this value may integrate different species and overlook putative ecotypes within species with different ecological roles (Fox et al., 1992; Acinas et al., 2004; Stackebrandt, 2006). Therefore, it is safe to assume that we detected at least between 1687 (at 97%) and 2385 (at 99%) putative new prokaryotic OTUs as well as 986 OTUs belonging to putative new genera (at 95%) not present in the standard prokaryotic rRNA gene databases (corresponding to 45.7%, 64.6% and a 26.7% of the total OTUs, respectively). However, these novel lineages represented a minor fraction of the reads (4.5%, 9.1% and 2.2%, respectively) and thus they are likely members of the bathypelagic ‘rare biosphere'. This pattern had already been observed in a single sample from a hydrothermal vent (Sogin et al., 2006) where novel sequences belonged to very low abundant OTUs. This result suggests that the prokaryotic assemblages in the bathypelagic ocean are composed of a combination of a set of relatively abundant and widely distributed species, already detected in previous environmental surveys, and a set of rare species with limited distributions where most of the genetic novelty accumulates.

Dominant prokaryotes in the bathypelagic ocean

We aimed at identifying the most abundant prokaryotes present in the deep ocean at a global scale. The relative abundance (that is, proportion of reads) of every phylum (except proteobacteria, which were divided into classes) was highly similar among samples (Supplementary Figure S6): Gammaproteobacteria, Alphaproteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Thaumarchaeota and Deltaproteobacteria dominated in all the stations in terms of relative abundance. Gammaproteobacteria was the most abundant group in all the sites, consistent with the previously described increase of their contribution to the total number of bacteria with depth (López-García et al., 2001). Here, the proportion of members of Archaea ranged from 2.2% to 16.3% of the total reads in both fractions combined. This estimation is considerably lower than previous studies in which Archaea had been reported to be between 20 and 30% of the total of bacterioplankton in the deep ocean (DeLong, 1992, 2003; Massana et al., 1997) or even higher (39%) (Karner et al., 2001). Yet, Archaea in the free-living samples reached up to 25–30% of the total in specific locations (stations 10, 81, 112, 118 and 121 located in the North Atlantic and North Pacific). Our findings are not attributable to PCR biases or primer mismatches as relative abundances of both Euryarchaeota and Thaumarchaeota obtained from the metagenomic data set were similar (Supplementary Figure S4). In all samples, Thaumarchaeota dominated over Euryarchaeota (1.7–14% vs 0.29–3.7%) as described before for bathypelagic waters (Herndl et al., 2005; Teira et al., 2006). Only the Actinobacteria phylum had differences in relative abundance between oceans and between deep-oceanic basins (as tested by analysis of variance with bonferroni correction: F=5.8, P=0.001, Pcorrected=0.016 and F=4.9, P=0.003, Pcorrected=0.045 for Ocean and Basins, respectively) being more abundant in the North and South Pacific and in particular the Pacific and Guatemala Basins.

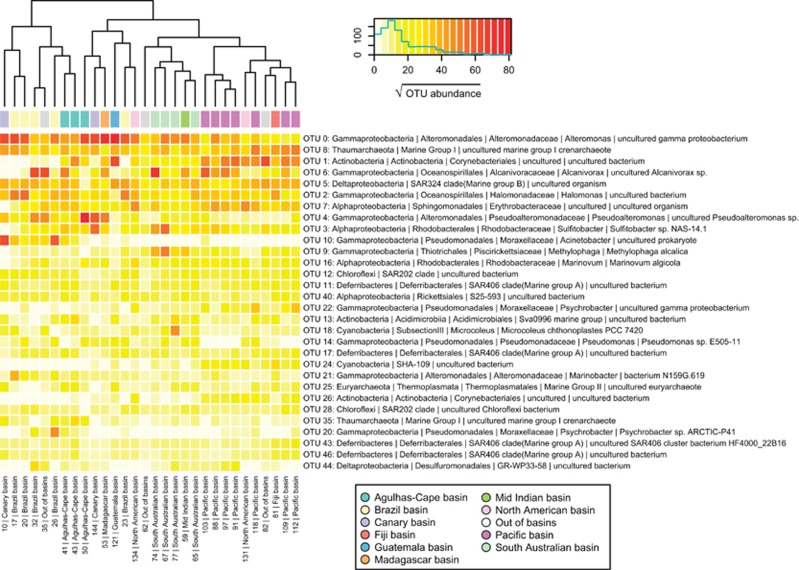

Despite the invariant composition of prokaryotic communities at a the phylum level, the distribution of the 30 most abundant OTUs (Figure 3,Supplementary Table S3) included only a few cosmopolitan organisms that were relatively evenly distributed along the whole data set: for example, the first, second and fifth most abundant OTUs, representatives of the Alteromonas genus, the Marine Group I Thaumarchaeota (MGI) and the SAR324 clade, respectively. This is consistent with current knowledge on the ecology of these three groups: the existence of a deep Alteromonas macleodii ecotype (identical at 16S rRNA gene sequence level to our most abundant OTU) with specific adaptations to deep-ocean conditions is well known (López-López et al., 2005; Ivars-Martinez et al., 2008) and the MGI archaeal group, jointly with Marine Group II Euryarchaeota, are the most abundant Archaea in the ocean (Massana et al., 2000). The SAR324 Deltaproteobacteria clade has also been described as a typical deep-sea group (López-García et al., 2001; Agogué et al., 2011). Most of the rest of the dominating OTUs exhibited uneven abundances throughout the world's deep oceans, with most of them restricted to a specific geographical region: for example, Alcanivorax sp. and an uncultured Actinobacteria representatives were nearly absent from the Atlantic, whereas a Pseudoalteromonas sp. representative was nearly absent from the Pacific but abundant in the rest of the sites. As a result of the heterogeneity in the distribution of the most abundant organisms, the samples tended to cluster with other geographically close samples (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Heatmap representing the square root of abundances (number of reads) of the 30 most abundant OTUs (rows) along the 30 stations (columns). Subsampled abundances to the minimum sequencing depth (10 617 reads per sample) have been used for comparison and data from the two size fractions within a station was summed after subsampling. The deep-oceanic basins to which each station belongs are indicated at the top (see color legend). Taxonomical annotation for each OTU is based on the SILVA taxonomic assignment of each OTU representative sequence. OTUs are ordered top to bottom based on their global abundance in the whole data set.

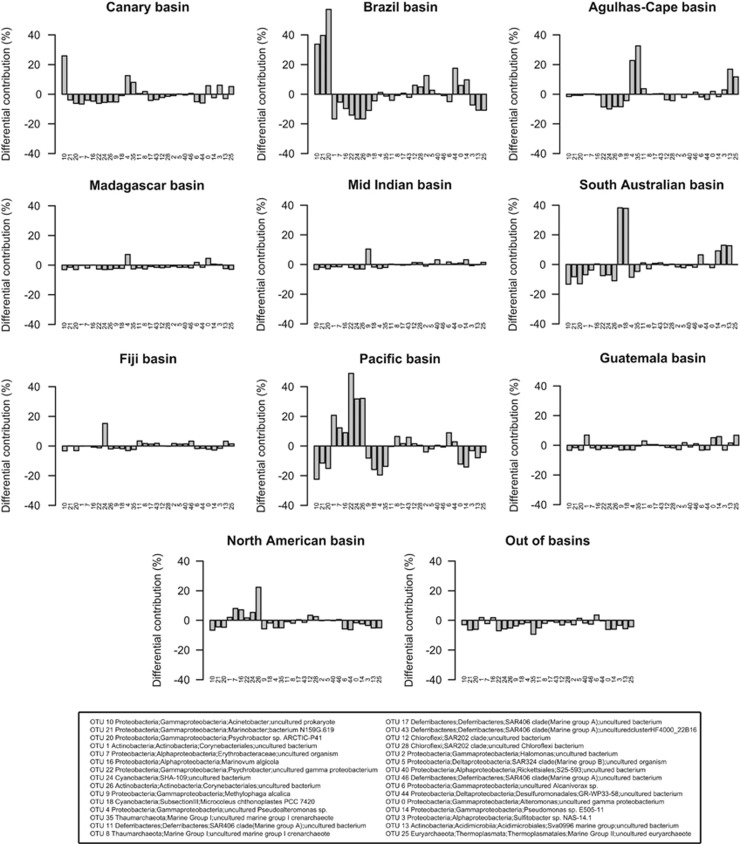

Differential OTU distribution through deep-oceanic basins

In addition, we calculated the differential contribution (in %) of a specific basin to the abundance of a specific OTU for the 30 most abundant OTUs (Figure 4). Within these, only a few did not have a clear differential contribution associated to a specific basin and thus, and as mentioned before (see Figure 3), these OTUs were equally distributed among basins (that is, were cosmopolitan): for example, members of the SAR406 clade and a representative of MGI and SAR324 clade. For the rest of the 30 most abundant OTUs, some were consistently overrepresented or underrepresented in each deep-ocean basin indicating that at least a fraction of the community exhibited an uneven distribution across basins. Representatives of the Acinetobacter and Pseudoalteromonas genus and MGI Thaumarchaeota were overrepresented in the Canary basin and underrepresented in the Pacific basin. Despite their proximity, the Brazil basin was characterized by a different combination of overrepresented OTUs: the same representative of the Acinetobacter genus was overrepresented in this basin but in combination with two OTUs assigned to the Marinobacter and Psychrobacter genus. A different OTU also assigned to the Psychrobacter genus was underrepresented in this basin but was especially abundant in the Pacific basin, together with two OTUs assigned to the Corynebacteriales order. The South Australian basin was characterized by the overrepresentation of two OTUs assigned to the Methylophaga and Microcoleus genus while the Agulhas-Cape basin had above-average contributions of the two OTUs assigned to Pseudoalteromonas genus and MGI that were abundant in the Canary basin but without the co-presence of Acinetobacter. Although the differential contribution was computed correcting for the different number of samples in each basin (details in the Supplementary Information), the deviation from an even distribution was higher for the basins with a higher number of samples (Brazil, South Australian and Pacific basin). Future studies with a higher spatial detail and sampling size within each basin would allow to define these basins in terms of prokaryotic community composition and to describe, if they exist, indicator OTUs or clades for the distinct basins.

Figure 4.

Differential contribution (Di,b; in %) of each basin to the total abundance of each of the 30 most abundant OTUs (see Supplementary Information for calculation details). Numbers below each bar represent each OTU, whose taxonomical affiliation is described in the legend, based on SILVA taxonomy. OTUs are the same as in Figure 3 but ordered using a clustering based on Di,b values (details not shown) for a clearer visualization.

Beta-diversity patterns of bathypelagic prokaryotic communities

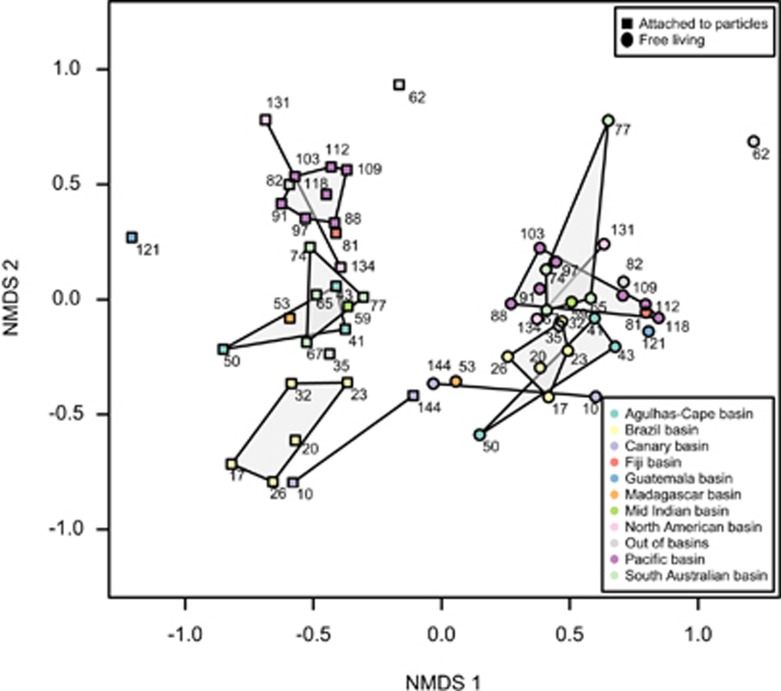

Non-metric multidimensional scaling was applied in order to represent the Bray–Curtis dissimilarities (that is, beta-diversity patterns) of the 60 samples (Figure 5) based on the relative abundance of all the OTUs. The samples belonging to different size fractions were clearly separated along the first axis. Detailed analysis of these differences is in the process (Salazar et al. in prep). Particle-attached samples within a deep-oceanic basin tended to have similar community composition, and thus clustered together in the non-metric multidimensional scaling. The seven samples located in the Pacific basin formed a tight cluster together with stations 81 (Fiji basin) and 88 (located also at the Pacific Ocean but at 2150 m depth and thus out of the basins defined below 3500 m). Samples belonging to the Brazil basin also clustered together and close to the samples from the Canary basin, both in the Atlantic Ocean. In contrast, the samples from stations 131 and 134 located also in the Atlantic Ocean and belonging to the same deep-water cluster but in a different basin, the North American basin, were more similar to the Pacific group. A third group of samples was composed by the stations situated in the Indian Ocean, in the South Australia basin, Madagascar basin and Mid Indian basin. This geographical ordering of the samples was not as evident for the free-living group of samples (Figure 5 and Figure 1 for sample location).

Figure 5.

Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) analysis of beta-diversity (Bray–Curtis distances) for the 60 samples in the data set based on iTags. Size-fraction is coded with point style (squares, attached and circles, free-living) and deep-oceanic basins following color codes (see legends). Numbers close to each sample represent the station number (see Figure 1).

A deep-ocean study has recently emphasized the role of distinct deep-sea water masses as potential bio-oceanographical islands for prokaryotic communities (Agogué et al., 2011). In addition, physical transport processes, such as advection, have been proved to act as ecological drivers of marine bacterial communities (Wilkins et al., 2013) but the effect of the deep ocean's floor morphology over the composition of microbial communities was only explored in few locations such as the Walvis Ridge or the Challanger Deep (Schauer et al., 2010; Nunoura et al., 2015). Here we test, at a global scale, the possibility that submarine mountains that divide the deep ocean into deep-oceanic basins may act as ‘ecological barriers' for prokaryotic communities: either by (i) imposing a reduced dispersion between basins or (ii) by compartmentalizing the bathypelagic ocean into contrasting environments that exert an ecological selection on the prokaryotes that inhabit it. In addition, we tested the relative role of water masses and deep-oceanic basins in shaping the biogeography of bathypelagic prokaryotes by examining the significance, tested using permutational multivariate analysis of variance, of the sample's clustering in accordance to the size-fraction, the deep-water cluster and deep-oceanic basins they belonged to (Supplementary Table S4). There were significant differences in the three factors (all P<0.0001) and they together explained almost 70% of the variance (size fraction, R2=0.31; deep-water cluster, R2=0.18; deep-oceanic basins, R2=0.18). None of the interactions between factors was significant. As most of the variance was explained by the size fraction, we split the analyses by size fraction to further test the deep-water cluster and basin as explanatory variables. Both factors were significant for the particle-attached fraction, and differences in oceanic basin origin explained 35% of the variance, even when taking the effect of deep-water clusters into account. For the free-living fraction there were no significant differences between oceanic basins once the deep-water clusters were considered. The date of sampling was included in the analyses to take into account seasonal differences as a possible confounding factor, as it has been shown that dark-ocean prokaryotic communities can be as dynamic as those of the surface ocean (Winter et al., 2009) where the seasonal patterns are extremely relevant (Brown et al., 2005; Fuhrman et al., 2006; Gilbert et al., 2009, 2012; Giovannoni, 2012). In all cases the date of sampling appeared to be a significant factor but its inclusion in the analyses did not modify the variance explained by the other factors (Supplementary Table S5). As the particulate matter in which particle-attached communities develop may ultimately come from the surface ocean through sinking, the Longhust provinces were also tested as a potential factor structuring the beta-diversity of free-living and particle-attached communities. In none of the two cases the grouping of the stations in the corresponding Longhust provinces was significant (details not shown). Thus, in summary, particle-attached prokaryotic communities exhibited a significant basin-specific composition, whereas this basin specificity was not observed for free-living prokaryotes. Consequently, different processes need to be structuring the particle-attached and free-living beta-diversity and thus generating differential biogeographical patterns.

Ecological processes shaping the biogeography of deep-ocean prokaryotic communities

The bathypelagic free-living and particle-attached prokaryotic communities clustered according to the water masses while only particle-attached communities exhibited a significant basin specificity. However, the biogeographical patterns observed can arise as the result of different ecological processes well established within a theoretical framework (Hanson et al., 2012): (a) the existence of environmental differences between basins or water masses that exert a differential selection of prokaryotes, that is, ‘environmental selection' or (b) a reduced dispersal of microbes between basins or water masses, that is, ‘historical effects'. We estimated the relative contribution of both processes by relating community composition to a set of environmental variables, and to the geographical distance between sampling locations, using multiple regression on matrices (see Supplementary Information for details and a further explanation of the theoretical framework). The multiple regression on matrices analysis explained a total of 23.1% (particle-attached fraction) and 10.7% (free-living fraction) of the total variance in the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity matrix. For the free-living fraction, only the effect of the environmental variables on community composition was statistically significant (P=0.005; explaining 6.4% of the variance) and the effect of the geographical distance was not (P>0.1), indicating that dispersal limitation and historical processes are not relevant in shaping the biogeography of free-living prokaryotes. However, dispersal limitation seemed to have a minor, yet significant, role for the particle-attached communities, as the pure effect of the geographical distance between locations explained a small but significant fraction of the variance (P<0.005; explaining a 5% of the variance). In addition, most of the variance was explained by the effect of the environmental variables (P<0.005), that is, the pure and the spatially structure environmental variation. These accounted for a 6.3% and 11.8% of the variance, respectively. Thus, both environmental selection and historical effects appear to shape the biogeography of particle-attached communities, although spurious distance effects may arise as a result of unmeasured environmental variables (Hanson et al., 2012).

The best subset of environmental drivers for the free-living fraction was temperature and depth of the sampling location (Table 1), pointing to a pure environmental selection process exerted by these two drivers for these communities. Temperature has also been found to be the main environmental driver for upper ocean microbial communities explaining the spatial variation within the epipelagic ocean (Sunagawa et al., 2015). In contrast, the best subsets of environmental drivers for the particle-attached fraction were the apparent oxygen utilization (AOU) and the prokaryotic biomass duplication time, although most of the effect was solely due to the AOU (Table 1). The AOU (that is, the difference between the saturation and measured dissolved oxygen) indicates the modification of oxygen concentration through the mixing of water masses and various biogeochemical processes and correlates with the aging of a water mass (Jenkins, 1982). In addition, in this case the AOU is clearly reflecting the deep-water clusters each sample belongs to (Supplementary Figure S2b). Thus, the fact that the AOU of the samples where particle-attached communities are found is the best explanatory variable suggest that water mass mixing and aging have an important role in the assembly of particle-attached bathypelagic communities.

Table 1. Environmental drivers of free-living and particle-attached communities.

| Environmental variable |

Particle-attached |

Free-living |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mantel r | P-value | Mantel r | P-value | |

| Depth | 0.145 | 0.11 | 0.261 | 0.06 |

| Salinity | 0.332 | <0.01* | 0.060 | 0.24 |

| Potential temperature | 0.156 | 0.01* | 0.124 | 0.07 |

| Apparent oxygen utilization | 0.426 | <0.01* | 0.077 | 0.17 |

| Prokaryotic heterotrophic activity | −0.156 | 0.93 | −0.170 | 0.94 |

| Prokaryote abundance | −0.156 | 0.90 | −0.145 | 0.86 |

| Percentage of HNA-content prokaryotes | −0.100 | 0.78 | −0.077 | 0.67 |

| Prokaryote biomass duplication time | 0.209 | 0.01* | 0.100 | 0.15 |

| Prokaryote abundance (0–200 m) | −0.145 | 0.95 | −0.059 | 0.67 |

| Best BIOENV model | 0.427 (AOU+DT) | <0.01* | 0.280 (depth+potential temperature) | 0.02* |

Abbreviation: HNA, high nucleic acid. Mantel correlation (using Pearson correlation) between the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity and the Euclidean distance for particle-attached and free-living prokaryotes of the environmental variables used in the BIOENV approach (see Supplementary Information). Single variables and the best BIOENV model for each fraction are tested. Significant P-values (<0.05) are indicated with an asterisk.

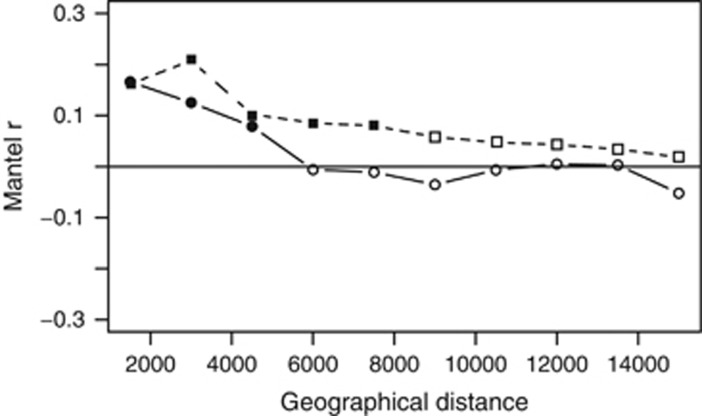

Finally, the scale of geographical variation for the two size fractions was studied using Mantel correlograms. We tested how far in space the samples maintain a significant autocorrelation in community composition. For particle-attached communities, there was a significant spatial autocorrelation, which expanded until 7500 km (Figure 6a). These relatively short distances, considering the global scale of the data set (that is, the ship covered ~45 700 km), are consistent with the basin-specificity of particle-attached prokaryotic community composition described above (Figure 5). In fact, the mean and maximal distance between all the samples belonging to the same deep-oceanic basin is 4950 and 9800 km, respectively. These distances are also coherent with the only study with a similar approach, which explored the effect of the Walvis Ridge on the bacterial communities in the deep-sea sediments at the Guinea, Angola and Cape basins, reporting an effect of the geographical distance on community composition detectable at distances >3000 km (Schauer et al., 2010). Although the effect of the geographical distance on community composition was not significant for the free-living communities once the effect of the environmental drivers is considered, there was a significant autocorrelation when tested at short distances, which expanded until 4500 km (Figure 6b). This significant autocorrelation found at short distances for the free-living communities does not correspond to the basin organization of the deep ocean, as tested before (Supplementary Tables S4 and S5), and may be due to the effect of potentially relevant environmental variables structuring the free-living bathypelagic communities at shorter scales, which were not measured in this study.

Figure 6.

Mantel correlogram for particle-attached (squares) and free-living (circles) prokaryotic communities testing the autocorrelation on community composition by performing sequential Mantel tests between the Bray–Curtis dissimilarities and the grouping of samples using geographical distance classes set at 1500 m. Filled points represent significant correlations after Bonferroni correction. Mantel correlograms were run up to a maximal distance of 15 000 km.

Thus, in summary, it seems that although both, the free-living and the particle-attached prokaryotic communities, exhibited autocorrelation at short distances and differ between water masses, they appeared to be structured by contrasting processes and drivers. The free-living prokaryotic communities appears to respond to an environmental selection process exerted by temperature and depth variations, although a high proportion of the variance remains unexplained (89.3%), as in similar studies (Hanson et al., 2012). In contrast, the particle-attached communities appear to respond to a more complex set of processes where the ageing and global circulation of the water masses and some degree of dispersal limitation create basin-specific communities not evident for the free-living fraction. This could be an indication that at least a fraction of the deep-oceanic particles where the prokaryotes are associated, instead of coming from the surface ocean through sinking, correspond to presumably buoyant or slow-sinking particles that are produced autochthonously at depth, as it has recently been hypothesized (Herndl and Reinthaler, 2013). This hypothesis would explain why particle-attached prokaryotes reflect the deep-water mass circulation and why a signal of reduced dispersal between basins is found only for particle-attached, and not for free-living communities.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation through project Consolider-Ingenio Malaspina 2010 (CSD2008-00077). We thank our fellow scientists and the crew and ship scientists of the different cruise legs for smooth operation. We particularly thank E Borrull, C Díez, E Lara and D Vaqué for help in DNA sampling and the rest of the microbiologists for sharing data. We would also like to thank the Physical Oceanography Malaspina team B2 for the acquisition, processing and calibration of the CTD data and TS Catalá for the help on delineating water masses. Sequencing at the Joint Genome Intitute was supported by US Department of Energy Joint Genome Intitute 2011 Microbes Program grant CSP 602 grant to SGA. The work conducted by the US Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute is supported by the Office of Science of the US Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02–05CH11231. We also thank R Logares and the Barcelona Supercomputer Center for providing access to the MareNostrum Supercomputer (grants BCV- 2011-2-0003/3-0005, 2012-1-0006/2-0002 to R Logares). Additional funding was provided by Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation grant CGL2011–26848/BOS MicroOcean PANGENOMICS and the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitivity grant MALASPINOMICS (CTM2011–15461-E). GS and FMCC held PhD JAE-Predoc (CSIC) and FPI (MICINN) fellowships respectively and SGA was supported by FP7-OCEAN-2011 project ‘Micro B3'.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on The ISME Journal website (http://www.nature.com/ismej)

Supplementary Material

References

- Acinas SG, Klepac-Ceraj V, Hunt DE, Pharino C, Ceraj I, Distel DL et al. (2004). Fine-scale phylogenetic architecture of a complex bacterial community. Nature 430: 551–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agogué H, Lamy D, Neal PR, Sogin ML, Herndl GJ. (2011). Water mass-specificity of bacterial communities in the North Atlantic revealed by massively parallel sequencing. Mol Ecol 20: 258–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen LZ, Allen EE, Badger JH, McCrow JP, Paulsen IT, Elbourne LD et al. (2012). Influence of nutrients and currents on the genomic composition of microbes across an upwelling mosaic. ISME J 6: 1403–1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 215: 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson MJ. (2001). A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol 26: 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson MJ, Walsh DCI. (2013). PERMANOVA, ANOSIM, and the Mantel test in the face of heterogeneous dispersions: What null hypothesis are you testing? Ecol Monogr 83: 557–574. [Google Scholar]

- Arístegui J, Gasol JM, Duarte CM, Herndl GJ. (2009). Microbial oceanography of the dark ocean's pelagic realm. Limnol Oceanogr 54: 1501–1529. [Google Scholar]

- Brown MV, Philip GK, Bunge JA, Smith MC, Bissett A, Lauro FM et al. (2009). Microbial community structure in the North Pacific ocean. ISME J 3: 1374–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MV, Schwalbach MS, Hewson I, Fuhrman JA. (2005). Coupling 16S-ITS rDNA clone libraries and automated ribosomal intergenic spacer analysis to show marine microbial diversity: development and application to a time series. Environ Microbiol 7: 1466–1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Walters Wa, Berg-Lyons D, Lozupone Ca, Turnbaugh PJ et al. (2011). Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108(Suppl): 4516–4522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke K, Ainsworth M. (1993). A method of linking multivariate community structure to environmental variables. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 92: 205–219. [Google Scholar]

- Cohan FM. (2002). What are bacterial species? Annu Rev Microbiol 56: 457–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole JR, Wang Q, Fish JA, Chai B, McGarrell DM, Sun Y et al. (2014). Ribosomal Database Project: data and tools for high throughput rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 42: D633–D642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crump BC, Armbrust EV, Baross JA. (1999). Phylogenetic analysis of particle-attached and free-living bacterial communities in the Columbia river, its estuary, and the adjacent coastal ocean. Appl Environ Microbiol 65: 3192–3204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLong EF. (1992). Archaea in coastal marine environments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89: 5685–5689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLong EF. (2003). Oceans of archaea. ASM News-American Soc Microbiol 69: 503. [Google Scholar]

- DeLong EF, Preston CM, Mincer T, Rich V, Hallam SJ, Frigaard N-U et al. (2006). Community genomics among stratified microbial assemblages in the ocean's interior. Science 311: 496–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eloe EA, Shulse CN, Fadrosh DW, Williamson SJ, Allen EE, Bartlett DH et al. (2011). Compositional differences in particle-associated and free-living microbial assemblages from an extreme deep-ocean environment. Environ Microbiol Rep 3: 449–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox GE, Wisotzkey JD, Jurtshuk P. (1992). How close is close: 16S rRNA sequence identity may not be sufficient to guarantee species identity. Int J Syst Bacteriol 42: 166–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrman JA, Hewson I, Schwalbach MS, Steele Ja, Brown MV, Naeem S. (2006). Annually reoccurring bacterial communities are predictable from ocean conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 13104–13109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galand PE, Potvin M, Casamayor EO, Lovejoy C. (2010). Hydrography shapes bacterial biogeography of the deep Arctic Ocean. ISME J 4: 564–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesh S, Parris DJ, DeLong EF, Stewart FJ. (2014). Metagenomic analysis of size-fractionated picoplankton in a marine oxygen minimum zone. ISME J 8: 187–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiglione J-F, Conan P, Pujo-Pay M. (2009). Diversity of total and active free-living vs particle-attached bacteria in the euphotic zone of the NW Mediterranean Sea. FEMS Microbiol Lett 299: 9–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiglione JF, Galand PE, Pommier T, Pedrós-Alió C, Maas EW, Bakker K et al. (2012). Pole-to-pole biogeography of surface and deep marine bacterial communities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 17633–17638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert JA, Field D, Swift P, Newbold L, Oliver A, Smyth T et al. (2009). The seasonal structure of microbial communities in the Western English Channel. Environ Microbiol 11: 3132–3139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert JA, Steele JA, Caporaso JG, Steinbrück L, Reeder J, Temperton B et al. (2012). Defining seasonal marine microbial community dynamics. ISME J 6: 298–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannoni SJ. (2012). Seasonality in ocean microbial communities. Science 335: 671–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagström Å, Pommier T, Rohwer F, Simu K, Stolte W, Svensson D et al. (2002). Use of 16S ribosomal DNA for delineation of marine bacterioplankton species. Appl Environ Microbiol 68: 3628–3633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdan LJ, Coffin RB, Sikaroodi M, Greinert J, Treude T, Gillevet PM. (2013). Ocean currents shape the microbiome of Arctic marine sediments. ISME J 7: 685–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson CA, Fuhrman JA, Horner-Devine MC, Martiny JBH. (2012). Beyond biogeographic patterns: processes shaping the microbial landscape. Nat Rev Microbiol 10: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herndl GJ, Reinthaler T. (2013). Microbial control of the dark end of the biological pump. Nat Geosci 6: 718–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herndl GJ, Reinthaler T, Teira E, van Aken H, Veth C, Pernthaler A et al. (2005). Contribution of Archaea to total prokaryotic production in the deep Atlantic Ocean. Appl Environ Microbiol 71: 2303–2309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irigoien X, Klevjer TA, Røstad A, Martinez U, Boyra G, Acuña JL et al. (2014). Large mesopelagic fishes biomass and trophic efficiency in the open ocean. Nat Commun 5: 3271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivars-Martinez E, Martin-Cuadrado A-B, D'Auria G, Mira A, Ferriera S, Johnson J et al. (2008). Comparative genomics of two ecotypes of the marine planktonic copiotroph Alteromonas macleodii suggests alternative lifestyles associated with different kinds of particulate organic matter. ISME J 2: 1194–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins WJ. (1982). Oxygen utilization rates in North Atlantic subtropical gyre and primary production in oligotrophic systems. Nature 300: 246–248. [Google Scholar]

- Karner MB, DeLong EF, Karl DM. (2001). Archaeal dominance in the mesopelagic zone of the Pacific Ocean. Nature 409: 507–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-García P, López-López A, Moreira D, Rodríguez-Valera F. (2001). Diversity of free-living prokaryotes from a deep-sea site at the Antarctic Polar Front. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 36: 193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-López A, Bartual SG, Stal L, Onyshchenko O, Rodríguez-Valera F. (2005). Genetic analysis of housekeeping genes reveals a deep-sea ecotype of Alteromonas macleodii in the Mediterranean Sea. Environ Microbiol 7: 649–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Cuadrado A-B, López-García P, Alba J-C, Moreira D, Monticelli L, Strittmatter A et al. (2007). Metagenomics of the deep Mediterranean, a warm bathypelagic habitat. PLoS One 2: e914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massana R, DeLong EF, Pedrós-Alió C. (2000). A few cosmopolitan phylotypes dominate planktonic archaeal assemblages in widely different oceanic provinces. Appl Environ Microbiol 66: 1777–1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massana R, Murray A, Preston C, DeLong E. (1997). Vertical distribution and phylogenetic characterization of marine planktonic Archaea in the Santa Barbara Channel. Appl Envir Microbiol 63: 50–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minchin PR. (1987). An evaluation of the relative robustness of techniques for ecological ordination. Vegetatio 69: 89–107. [Google Scholar]

- Moalic Y, Desbruyères D, Duarte CM, Rozenfeld AF, Bachraty C, Arnaud-Haond S. (2012). Biogeography revisited with network theory: retracing the history of hydrothermal vent communities. Syst Biol 61: 127–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunoura T, Takaki Y, Hirai M, Shimamura S, Makabe A, Koide O. (2015). Hadal biosphere: insight into the microbial ecosystem in the deepest ocean on Earth. Proc Natl Acad Sci 112: E1230–E1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oden NL, Sokal RR. (1986). Directional autocorrelation: an extension of spatial correlograms to two dimensions. Syst Zool 35: 608. [Google Scholar]

- Pedrós-Alió C. (2012). The rare bacterial biosphere. Ann Rev Mar Sci 4: 449–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruesse E, Quast C, Knittel K, Fuchs BM, Ludwig W, Peplies J et al. (2007). SILVA: a comprehensive online resource for quality checked and aligned ribosomal RNA sequence data compatible with ARB. Nucleic Acids Res 35: 7188–7196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt KD, Tatusova T, Brown GR, Maglott DR. (2012). NCBI Reference Sequences (RefSeq): current status, new features and genome annotation policy. Nucleic Acids Res 40: D130–D135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quaiser A, Zivanovic Y, Moreira D, López-García P. (2011). Comparative metagenomics of bathypelagic plankton and bottom sediment from the Sea of Marmara. ISME J 5: 285–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2014), R: A language and environment for statistical computing.

- Rusch DB, Halpern AL, Sutton G, Heidelberg KB, Williamson S, Yooseph S et al. (2007). The Sorcerer II Global Ocean Sampling expedition: northwest Atlantic through eastern tropical Pacific. PLoS Biol 5: e77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauer R, Bienhold C, Ramette A, Harder J. (2010). Bacterial diversity and biogeography in deep-sea surface sediments of the South Atlantic Ocean. ISME J 4: 159–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedile F, Messina E, La Cono V, Tsoy O, Monticelli LS, Borghini M et al. (2012). Metagenomic analysis of hadopelagic microbial assemblages thriving at the deepest part of Mediterranean Sea, Matapan-Vavilov Deep. Environ Microbiol 15: 167–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sogin ML, Morrison HG, Huber JA, Mark Welch D, Huse SM, Neal PR et al. (2006). Microbial diversity in the deep sea and the underexplored ‘rare biosphere'. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 12115–12120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stackebrandt E. (2006) Defining Taxonomic Ranks. In: Dworkin M, Falkow S, Rosenberg E, Schleifer K-H, Stackebrandt E (eds). The Prokaryotes SE—3. Springer: New York, NY, USA, pp 29–57. [Google Scholar]

- Stackebrandt E, Goebel BM. (1994). Taxonomic note: a place for DNA-DNA reassociation and 16S rRNA sequence analysis in the present species definition in bacteriology. Int J Syst Bacteriol 44: 846–849. [Google Scholar]

- Sul WJ, Oliver Ta, Ducklow HW, Amaral-Zettler La, Sogin ML. (2013). Marine bacteria exhibit a bipolar distribution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA pp 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sunagawa S, Coelho LP, Chaffron S, Kultima JR, Labadie K, Salazar G et al. (2015). Structure and function of the global ocean microbiome. Science 348: 1261359–1261359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teira E, Lebaron P, van Aken H, Herndl GJ. (2006). Distribution and activity of Bacteria and Archaea in the deep water masses of the North Atlantic. Limnol Oceanogr 51: 2131–2144. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Cao H, Zhang G, Bougouffa S, Lee OO, Al-Suwailem A et al. (2013). Autotrophic microbe metagenomes and metabolic pathways differentiate adjacent red sea brine pools. Sci Rep 3: 1748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins D, van Sebille E, Rintoul SR, Lauro FM, Cavicchioli R. (2013). Advection shapes Southern Ocean microbial assemblages independent of distance and environment effects. Nat Commun 4: 2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter C, Kerros M-E, Weinbauer MG. (2009). Seasonal changes of bacterial and archaeal communities in the dark ocean: evidence from the Mediterranean Sea. Limnol Oceanogr 54: 160–170. [Google Scholar]

- Yooseph S, Sutton G, Rusch DB, Halpern AL, Williamson SJ, Remington K et al. (2007). The Sorcerer II Global Ocean Sampling expedition: expanding the universe of protein families. PLoS Biol 5: e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinger L, Amaral-Zettler La, Fuhrman Ja, Horner-Devine MC, Huse SM, Welch DBM et al. (2011). Global Patterns of Bacterial Beta-Diversity in Seafloor and Seawater Ecosystems. In: Gilbert, JA (ed). PLoS One 6: e24570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.