Abstract

Epidermolysis bullosa encompasses a group of inherited connective tissue disorders that range from mild to lethal. There is no cure, and current treatment is limited to palliative care that is largely ineffective in treating the systemic, life-threatening pathology associated with the most severe forms of the disease. Although allogeneic cell- and protein-based therapies have shown promise, both novel and combinatorial approaches will undoubtedly be required to totally alleviate the disorder. Progress in the development of next-generation therapies that synergize targeted gene-correction and induced pluripotent stem cell technologies offers exciting prospects for personalized, off-the-shelf treatment options that could avoid many of the limitations associated with current allogeneic cell-based therapies. Although no single therapeutic avenue has achieved complete success, each has substantially increased our collective understanding of the complex biology underlying the disease, both providing mechanistic insights and uncovering new hurdles that must be overcome.

Butterfly Children

Children born with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (RDEB), a severe inherited disorder of connective tissue, are often referred to as “butterfly children,” because the fragility of their skin can be compared to the delicateness of a butterfly wing. Individuals with RDEB endure chronic pain and daily challenges brought on by severe cutaneous and mucosal blistering, joint contractures, pseudosyndactyly, corneal abrasions, esophageal strictures, and impaired wound healing that contribute to significant morbidity and a shortened life span.1,2,3,4 At present, palliative care is the only option widely available to RDEB patients, and it is limited to intricate and laborious bandaging, pain and itch control, and management of bacterial and fungal infection. Even with proper care, RDEB patients often develop chronic cutaneous infections and are prone to developing aggressive squamous cell carcinomas later in life.5,6

Recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (RDEB) is inherited in autosomal-recessive fashion.7,8 Generalized severe (GS) RDEB, the physical manifestations of the most severe form, is caused by mutations to the gene encoding type VII collagen (C7), COL7A1. Mechanistically, C7 is essential to the formation of anchoring fibrils that secure the epidermis to the underlying dermis at the dermal-epidermal junction.9,10,11,12 In the absence of functional C7, these layers of skin do not adhere properly, and severe blistering occurs after minimal trauma. Subsequent wound healing is also impaired.13

Over the past several years, exciting progress has been made in the treatment of RDEB. In particular, allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) has shown the ability to partially correct the systemic manifestations of RDEB-GS.14 Although these pioneering efforts are changing the collective perspective on RDEB treatment, the significant morbidity and mortality associated with HCT, along with the inability of other therapies to treat systemic symptoms, necessitate the development of novel therapies that overcome these limitations while still providing durable, effective amelioration of systemic RDEB pathology.

Repairing the Matrix with Marrow

The earliest efforts to treat the cutaneous manifestations of RDEB with cellular therapy employed intradermal injections of allogeneic fibroblasts and mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs).15,16,17,18,19 Although these avenues of treatment show promise for restoring localized C7, they are not able to address the underlying systemic manifestations of epidermolysis bullosa (EB). Furthermore, as these cell populations do not contain self-renewing stem cells, the benefits are likely to be transient.

Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is the most widely employed stem cell therapy and the only one capable of providing durable and systemic delivery of donor cells upon transplantation.20,21 Although HCT carries a proven track record in the treatment of hematological diseases and genetic enzymopathies, employing HCT to treat a disease of the extracellular matrix (ECM) initially flew in the face of prevailing wisdom. Nonetheless, well-documented examples of donor cell chimerism in the skin and mucosal epithelia of transplant recipients suggested that HCT could prove beneficial to patients with RDEB.22,23,24,25 Although cells of hematopoietic origin play important roles in mediating the inflammatory response to injury, evidence is accumulating that suggests they have a more direct role in skin repair.26,27

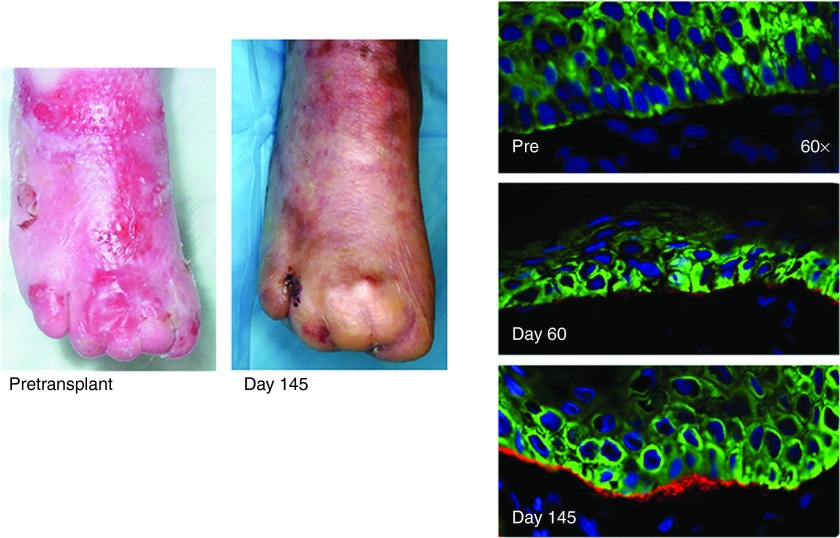

Initial studies involving the transfer of marrow cells from 8-week-old green fluorescent protein-positive mice into the circulation of day 13 col7a1-/- embryos (embryonic bone marrow transplant (E-BMT)) demonstrated the capacity of bone marrow cells to contribute dermal fibroblasts and prolong survival.28 As the fetal microenvironment is believed to foster cellular plasticity, it was not immediately clear that the results obtained via E-BMT could be reproduced in postnatal recipients. To address this question, subsets of marrow-derived cells were transplanted into neonatal col7a1-/- mice, with the result that bone marrow-derived cells migrated to the skin, mediated C7 deposition, and prolonged the survival of col7a1-/- mice.29 These preclinical studies paved the way for the first human trials using HCT to treat RDEB-GS. The children with RDEB-GS also exhibited significant donor chimerism in the skin after HCT, which coincided with C7 deposition at the cutaneous basement membrane and improvement in skin integrity and wound healing as seen in an image from clinical trials showing phenotypic correction and C7 deposition (Figure 1).14 While these results are undoubtedly promising, a number of questions remain regarding the cell type or types responsible for mediating the deposition of C7 after HCT.

Figure 1.

Images of patient wounds on the right foot pretransplant and again at day 145. Data taken from ref. 14.

Bone marrow-derived fibroblast-like cells capable of migrating to wounds and depositing ECM proteins were identified as early as 1994.30 These so-called fibrocytes are bone marrow-originating cells that express both hematopoietic surface antigens, such as CD34 and CD45, as well as a number of ECM proteins.31 Based on their shared expression of several monocyte and macrophage surface antigens, fibrocytes are thought to arise from a subpopulation of monocytes, and their formation can be promoted by the presence of inflammatory cytokines.32 Upon injury, fibrocytes are involved in modulating the inflammatory response,33 promoting tissue remodeling and angiogenesis,34 and inducing α-smooth muscle actin-positive myofibroblasts from fibroblasts via the secretion of paracrine factors such as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and transforming growth factor-β1.35 Interestingly, lineage-tracing studies in a hematopoietic-specific Vav1-cre model identified a previously undescribed fibrocyte population lacking prototypical hematopoietic surface markers (such as CD45 and CD11b), suggesting that a subset of early blood progenitors is able to give rise to wound-resident cells that may not be readily discernable from dermal fibroblasts by simple surface antigen phenotype.36 It is yet to be explored whether donor-derived fibrocyte populations play a role in C7 deposition after transplant.

Beyond the relatively well-defined fibrocyte, it has been shown that bone marrow-derived cells are capable of engrafting into hair follicles and undergoing transdifferentiation into keratinocytes after transplantation.37,38 Although transdifferentiation of hematopoietic progenitors has been suggested,23,39 in the studies reporting this phenomenon, the transplanted population was either not well defined or too heterogeneous to definitively prove a hematopoietic origin. Indeed, when highly purified hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) were transplanted, there was little evidence of transdifferentiation, indicating that any such event is extremely rare in vivo.40 It is unknown whether the active wounds and consequent inflammatory milieu present in RDEB-GS patients receiving HCT create an environment permissive to the transdifferentiation of hematopoietic progenitors.

There is stronger evidence to suggest that non-hematopoietic bone marrow-derived cells such as MSCs are capable of integrating into diverse tissues and are responsible for generating keratinocytes present in epithelial tissues after bone marrow transplant (BMT).41,42,43 Not surprisingly, MSCs share a similar gene-expression profile with dermal fibroblasts, including the expression of ECM proteins such as C7.44 Recently, a previously undescribed bone marrow-resident population identified as lineage marker negative, PDGF receptor α-positive (Lin-PDGFRα+) was shown to home to skin grafts and generate functional keratinocytes capable of depositing C7.45 Importantly, the authors identified the high-mobility group box protein HMGB1 as playing a key role in the homing of bone marrow-derived Lin-PDGFRα+ cells to sites of cutaneous injury. Follow-up studies by the same group demonstrated that these lineage marker (CD3e, CD11b, B220, TER-119, Ly-6G, and Ly6C) negative, PDGFRα+ mesenchymal cells homed to RDEB skin grafted onto wild-type mice in a SDF-1α/CXCR4 axis-dependent manner, suggesting that manipulation of either the stromal-derived factor 1 or HMGB1-signaling pathways could be used to improve trafficking of donor cells to the skin posttransplant.46

Cells Made to Order: The Promise of Induced Pluripotency and Cellular Plasticity

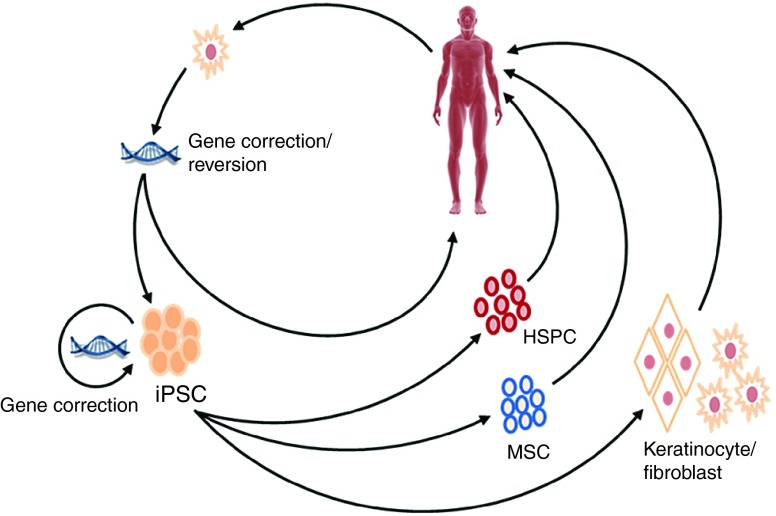

The demonstration that somatic cells could be reprogrammed to pluripotency has opened new doors in the field of regenerative medicine.47,48 Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) represent, in principle, a nearly inexhaustible source of somatic cell types for tissue regeneration and ex vivo modeling of genetic disease (Figure 2).49,50,51 Skin cells from RDEB patients, as well as the closely related junctional form of EB (JEB), can be reprogrammed to pluripotency, thereby providing new tools with which to investigate the mechanisms underlying EB pathology in vitro.52,53 Perhaps, the most direct route to iPSC-based cell therapies for RDEB comes via the frequent occurrence of somatic mosaicism in RDEB patients.54,55 Keratinocytes from these healthy patches of skin can be used directly,56,57,58 or they can be reprogrammed to pluripotency and subsequently used as a source of autologous cells for therapeutic intervention.59,60 These naturally gene-corrected iPSCs can be differentiated into C7-producing fibroblasts and keratinocytes, as well as three-dimensional skin equivalents that are well suited for localized treatment of chronic wounds.61,62,63,64,65 Ideally, iPSC could be utilized to generate epidermal stem cells capable of regenerating all components of adult skin,66 and indeed progress is being made in this area.67 Nevertheless, as skin-resident cell types derived from iPSC will not be sufficient to address the systemic pathology associated with RDEB, it is necessary to identify alternate strategies to overcome this issue.

Figure 2.

Potential strategies to implement next-generation therapies in the treatment of recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. In this diagram, mutant or naturally gene-reverted cells are isolated from the patient, and mutant cells are gene corrected. These cells are then either used directly or reprogrammed in to induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). If gene correction of primary cells is not possible, the gene correction step can be performed at the iPSC stage. The gene-corrected iPSCs are subsequently differentiated into hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells and/or mesenchymal stem cells for systemic administration, or keratinocytes and/or fibroblasts for localized application.

Although iPSC can be readily differentiated into nearly all mature hematopoietic lineages in vitro, derivation of HSC capable of long-term reconstitution has not yet been demonstrated.68,69,70,71,72 However, two recent studies demonstrated the formation of HSC from iPSC within teratoma, suggesting that this conversion is possible if the appropriate environmental cues are present.73,74 The identification of new small molecule modulators of HSC differentiation and expansion offers fresh opportunities in the efforts to derive HSC from iPSC.75,76,77,78,79 Intriguingly, several studies have begun to identify methods for direct conversion of somatic cells into hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells, bypassing pluripotency altogether.80,81,82 While undoubtedly exciting, these methods of transdifferentiation require genetic manipulation that is not suitable for translational efforts, although future modifications that do not rely on multiple integrated vectors could overcome these issues. In the interim, methods for the generation of iPSC-derived non-stem subsets of C7-producing hematopoietic cells could prove beneficial, as these cells could conceivably provide systemic, albeit transient, delivery of C7.

Another option to address the systemic manifestations of RDEB with iPSC could come via the delivery of iPSC-derived non-hematopoietic MSCs. Although strategies for the differentiation of iPSC to MSC have been reported,83,84,85 it is unclear whether the iPSC–MSC described in these studies are similar to the mouse Lin-PDGFRα+ mesenchymal cells in their capacity to migrate to wounds and mediate C7 deposition. Further characterization of iPSC–MSC in the setting of RDEB is warranted and, if necessary, modified differentiation protocols to generate cells tailored for this specific purpose should be developed.

To realize the full benefit of reprogramming technology in RDEB, it needs to be combined with gene correction—such as with viral-mediated gene addition or with gene-editing strategies—to allow customized autologous cellular therapies tailored to the needs of each individual patient.

Gene Therapy: Cutting to the Cure

Despite the long and successful track record of HCT in the treatment of genetic disease,86,87,88,89 there remain significant limitations to the procedure. The requirement for a human leucocyte antigen-matched donor prevents the use of HCT in some cases, and even when a matched donor is available, the procedure itself carries a significant risk of morbidity and mortality.90,91,92,93 Gene-correction and reintroduction of autologous cells would overcome many of the limitations associated with allogeneic cell therapies. A number of viral- and transposon-based vectors have been used to reintroduce wild-type C7 into RDEB and JEB cells.94,95,96,97 Long-term follow-up (6.5 years) of a patient who received retrovirally corrected epidermal stem cell grafts for JEB shows restoration of skin integrity and no clinically obvious adverse effects.98 Although several recent reports have demonstrated the safety of lentiviral- and retroviral-mediated gene therapies in humans,99,100,101,102 there remains appreciable trepidation due to previous adverse events in trials using retroviral vectors.103 Beyond the risk of insertional mutagenesis, the long-term effects of supraphysiological expression of ECM proteins are unknown. Considering the evidence that perturbation of the expression of ECM proteins can impact the cellular microenvironment,104 it might be preferable to develop gene-editing strategies that correct the causative mutation in situ. Toward this end, Melo et al.105 report successful homologous recombination (HR)-mediated gene correction of a mutation in the LAMA3 locus in primary human keratinocytes using a highly recombinogenic adeno-associated virus (AAV-DJ) vector, thus limiting the risk of insertional mutagenesis.

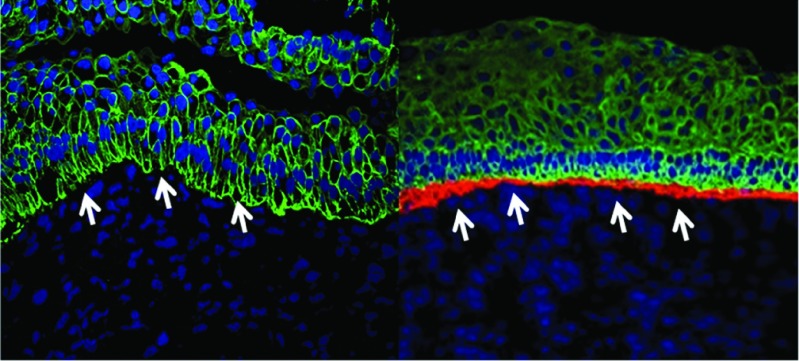

The rapid advancement in designer nuclease technologies has ushered in an era where HR in human cells is not only possible, but also reaching the efficiency required for therapeutic application.106,107,108 As a proof of concept, transcription activator-like effector nucleases were utilized to mediate homologous repair of COL7A1 in patient fibroblasts with minimal off-target activity (Figure 3).109 These gene-corrected fibroblasts were selected and subsequently reprogrammed to iPSC and shown to be capable of generating three-dimensional skin structures with appropriate deposition of C7 protein. More recently, the demonstration of HR-mediated gene correction in human-repopulating HSC has opened doors to autologous HCT for RDEB.110

Figure 3.

Teratoma immunofluorescence shows the dermal-epidermal junction indicated with white arrows. The immunofluorescence markers are as follows: blue, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) nuclear stain; green, cytokeratin 5; and red, type VII collagen. Images are representative images from at least three animals. Antibody staining was performed from a single master mix on the same day using identical microscopy settings. Data taken from ref. 109.

Moving forward, the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats and associated nucleases (CRISPR/Cas) system should allow for expedited reagent generation, making it highly suited to gene-correction strategies for the large number of unique mutations associated with EB.111,112,113 While the safety profile of designer nuclease technologies is still being assessed, future modifications will likely enhance efficiency and specificity, and as such these reagents might represent the future of gene therapy for RDEB.

Although recent proof-of-concept studies using both iPSC and gene-editing technologies demonstrate their immense potential to treat RDEB, a substantial effort will be required in order to move these strategies from the bench to the bedside. Toward this end, methods for reprogramming and gene modification under good manufacturing practices have been demonstrated.114 Subsequent efforts should focus on thorough characterization of gene-corrected iPSCs and the safety of their derivative cell types in vivo.

The Future of Regenerative Medicine: Implications for RDEB Treatment

Simultaneous and significant advances in the fields of cellular reprogramming and genome engineering have set the stage for entry into an era of revolutionary advances in regenerative medicine, a field in which the delicate balances between the genome, the cell, and the patient must be carefully and methodically explored. This is particularly relevant to the treatment of RDEB, where the complex and systemic manifestations of the disease will likely require combinatorial therapies in order to achieve the ultimate goal.115 For example, although HCT provides systemic long-term benefits and creates immune tolerance to donor C7 protein, some individuals with severe, chronic wounds may further benefit from the localized delivery of skin-resident cells or skin grafts to augment healing. Fibroblasts and/or keratinocytes from the HCT donor could be employed to enhance repair in these situations, as even microchimerism has been shown to mediate immunological tolerance and acceptance of grafts.116 Further, for corneal abrasions, one of the most debilitating clinical features of RDEB-GS, limbal stem cell populations could prove beneficial.3,117,118 Eventually, autologous gene-corrected iPSC could be used to generate all of the aforementioned cell types on demand. This could be an ideal situation, as only a single gene-modification step would be necessary and only the iPSC clones with a validated safety profile and lack of off-target mutations would be retained for use.114 Although this review has focused primarily on cell- and gene-based therapies for RDEB, future treatment strategies will also likely incorporate the use of recombinant C7 alone or boost the therapeutic effects of cell-based interventions.119,120,121 Pharmacological interventions could also prove beneficial, whether via the restoration of wild-type C7 expression from premature termination signals122 or via the promotion of marrow stem cell mobilization to cutaneous wounding post-BMT.123 Which combinations of these therapies will ultimately result in a cure for RDEB is yet to be determined; however, it is certain that the lessons learned along the way will have a widespread impact on the future of regenerative medicine.

References

- Horn, HM and Tidman, MJ (2002). Quality of life in epidermolysis bullosa. Clin Exp Dermatol 27: 707–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uitto, J, Pulkkinen, L and McLean, WH (1997). Epidermolysis bullosa: a spectrum of clinical phenotypes explained by molecular heterogeneity. Mol Med Today 3: 457–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine, JD, Johnson, LB, Weiner, M, Stein, A, Cash, S, Deleoz, J et al. (2004). Eye involvement in inherited epidermolysis bullosa: experience of the National Epidermolysis Bullosa Registry. Am J Ophthalmol 138: 254–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruckner-Tuderman, L (2010). Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: pathogenesis and clinical features. Dermatol Clin 28: 107–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South, AP and O'Toole, EA (2010). Understanding the pathogenesis of recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Clin 28: 171–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourreyron, C, Cox, G, Mao, X, Volz, A, Baksh, N, Wong, T et al. (2007). Patients with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa develop squamous-cell carcinoma regardless of type VII collagen expression. J Invest Dermatol 127: 2438–2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovnanian, A, Duquesnoy, P, Blanchet-Bardon, C, Knowlton, RG, Amselem, S, Lathrop, M et al. (1992). Genetic linkage of recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa to the type VII collagen gene. J Clin Invest 90: 1032–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine, JD, Bruckner-Tuderman, L, Eady, RA, Bauer, EA, Bauer, JW, Has, C et al. (2014). Inherited epidermolysis bullosa: updated recommendations on diagnosis and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol 70: 1103–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousselle, P, Keene, DR, Ruggiero, F, Champliaud, MF, Rest, M and Burgeson, RE (1997). Laminin 5 binds the NC-1 domain of type VII collagen. J Cell Biol 138: 719–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegener, H, Leineweber, S and Seeger, K (2013). The vWFA2 domain of type VII collagen is responsible for collagen binding. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 430: 449–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai, LY, Keene, DR, Morris, NP and Burgeson, RE (1986). Type VII collagen is a major structural component of anchoring fibrils. J Cell Biol 103: 1577–1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruckner-Tuderman, L and Has, C (2014). Disorders of the cutaneous basement membrane zone–the paradigm of epidermolysis bullosa. Matrix Biol 33: 29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyström, A, Velati, D, Mittapalli, VR, Fritsch, A, Kern, JS and Bruckner-Tuderman, L (2013). Collagen VII plays a dual role in wound healing. J Clin Invest 123: 3498–3509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, JE, Ishida-Yamamoto, A, McGrath, JA, Hordinsky, M, Keene, DR, Woodley, DT et al. (2010). Bone marrow transplantation for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. N Engl J Med 363: 629–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong, T, Gammon, L, Liu, L, Mellerio, JE, Dopping-Hepenstal, PJ, Pacy, J et al. (2008). Potential of fibroblast cell therapy for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. J Invest Dermatol 128: 2179–2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern, JS, Loeckermann, S, Fritsch, A, Hausser, I, Roth, W, Magin, TM et al. (2009). Mechanisms of fibroblast cell therapy for dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: high stability of collagen VII favors long-term skin integrity. Mol Ther 17: 1605–1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venugopal, SS, Yan, W, Frew, JW, Cohn, HI, Rhodes, LM, Tran, K et al. (2013). A phase II randomized vehicle-controlled trial of intradermal allogeneic fibroblasts for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. J Am Acad Dermatol 69: 898–908.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrof, G, Martinez-Queipo, M, Mellerio, JE, Kemp, P and McGrath, JA (2013). Fibroblast cell therapy enhances initial healing in recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa wounds: results of a randomized, vehicle-controlled trial. Br J Dermatol 169: 1025–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conget, P, Rodriguez, F, Kramer, S, Allers, C, Simon, V, Palisson, F et al. (2010). Replenishment of type VII collagen and re-epithelialization of chronically ulcerated skin after intradermal administration of allogeneic mesenchymal stromal cells in two patients with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Cytotherapy 12: 429–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, ED, Lochte, HL Jr, Lu, WC and Ferrebee, JW (1957). Intravenous infusion of bone marrow in patients receiving radiation and chemotherapy. N Engl J Med 257: 491–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatti, RA, Meuwissen, HJ, Allen, HD, Hong, R and Good, RA (1968). Immunological reconstitution of sex-linked lymphopenic immunological deficiency. Lancet 2: 1366–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause, DS, Theise, ND, Collector, MI, Henegariu, O, Hwang, S, Gardner, R et al. (2001). Multi-organ, multi-lineage engraftment by a single bone marrow-derived stem cell. Cell 105: 369–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Körbling, M, Katz, RL, Khanna, A, Ruifrok, AC, Rondon, G, Albitar, M et al. (2002). Hepatocytes and epithelial cells of donor origin in recipients of peripheral-blood stem cells. N Engl J Med 346: 738–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata, H, Janin, A, Leboeuf, C, Soulier, J, Gluckman, E, Meignin, V et al. (2007). Donor-derived cells and human graft-versus-host disease of the skin. Blood 109: 2663–2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan, FM, Sy, S, Louie, P, Smith, M, Chernos, J, Berka, N et al. (2010). Nasal epithelial cells of donor origin after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation are generated at a faster rate in the first 3 months compared with later posttransplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 16: 1658–1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arwert, EN, Hoste, E and Watt, FM (2012). Epithelial stem cells, wound healing and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 12: 170–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y, Zhao, RC and Tredget, EE (2010). Concise review: bone marrow-derived stem/progenitor cells in cutaneous repair and regeneration. Stem Cells 28: 905–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chino, T, Tamai, K, Yamazaki, T, Otsuru, S, Kikuchi, Y, Nimura, K et al. (2008). Bone marrow cell transfer into fetal circulation can ameliorate genetic skin diseases by providing fibroblasts to the skin and inducing immune tolerance. Am J Pathol 173: 803–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolar, J, Ishida-Yamamoto, A, Riddle, M, McElmurry, RT, Osborn, M, Xia, L et al. (2009). Amelioration of epidermolysis bullosa by transfer of wild-type bone marrow cells. Blood 113: 1167–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucala, R, Spiegel, LA, Chesney, J, Hogan, M and Cerami, A (1994). Circulating fibrocytes define a new leukocyte subpopulation that mediates tissue repair. Mol Med 1: 71–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney, J, Bacher, M, Bender, A and Bucala, R (1997). The peripheral blood fibrocyte is a potent antigen-presenting cell capable of priming naive T cells in situ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 6307–6312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilkoff, RA, Bucala, R and Herzog, EL (2011). Fibrocytes: emerging effector cells in chronic inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 11: 427–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney, J, Metz, C, Stavitsky, AB, Bacher, M and Bucala, R (1998). Regulated production of type I collagen and inflammatory cytokines by peripheral blood fibrocytes. J Immunol 160: 419–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartlapp, I, Abe, R, Saeed, RW, Peng, T, Voelter, W, Bucala, R et al. (2001). Fibrocytes induce an angiogenic phenotype in cultured endothelial cells and promote angiogenesis in vivo. FASEB J 15: 2215–2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, JF, Jiao, H, Stewart, TL, Shankowsky, HA, Scott, PG and Tredget, EE (2007). Fibrocytes from burn patients regulate the activities of fibroblasts. Wound Repair Regen 15: 113–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga, H, Rennert, RC, Rodrigues, M, Sorkin, M, Glotzbach, JP, Januszyk, M et al. (2014). Tracking the elusive fibrocyte: identification and characterization of collagen-producing hematopoietic lineage cells during murine wound healing. Stem Cells 32: 1347–1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badiavas, EV, Abedi, M, Butmarc, J, Falanga, V and Quesenberry, P (2003). Participation of bone marrow derived cells in cutaneous wound healing. J Cell Physiol 196: 245–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borue, X, Lee, S, Grove, J, Herzog, EL, Harris, R, Diflo, T et al. (2004). Bone marrow-derived cells contribute to epithelial engraftment during wound healing. Am J Pathol 165: 1767–1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, Y, Abe, R, Inokuma, D, Sasaki, M, Hoshina, D, Natsuga, K et al. (2010). Bone marrow transplantation restores epidermal basement membrane protein expression and rescues epidermolysis bullosa model mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 14345–14350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagers, AJ, Sherwood, RI, Christensen, JL and Weissman, IL (2002). Little evidence for developmental plasticity of adult hematopoietic stem cells. Science 297: 2256–2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y, Chen, L, Scott, PG and Tredget, EE (2007). Mesenchymal stem cells enhance wound healing through differentiation and angiogenesis. Stem Cells 25: 2648–2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng, W, Han, Q, Liao, L, Li, C, Ge, W, Zhao, Z et al. (2005). Engrafted bone marrow-derived flk-(1+) mesenchymal stem cells regenerate skin tissue. Tissue Eng 11: 110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, S, Huss, R, Schulz-Siegmund, M, Vogel, B, Brandau, S, Lang, S et al. (2014). Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells migrate to healthy and damaged salivary glands following stem cell infusion. Int J Oral Sci 6: 154–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexeev, V, Uitto, J and Igoucheva, O (2011). Gene expression signatures of mouse bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in the cutaneous environment and therapeutic implications for blistering skin disorder. Cytotherapy 13: 30–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamai, K, Yamazaki, T, Chino, T, Ishii, M, Otsuru, S, Kikuchi, Y et al. (2011). PDGFRalpha-positive cells in bone marrow are mobilized by high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) to regenerate injured epithelia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 6609–6614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iinuma, S, Aikawa, E, Tamai, K, Fujita, R, Kikuchi, Y, Chino, T et al. (2015). Transplanted bone marrow-derived circulating PDGFRα+ cells restore type VII collagen in recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa mouse skin graft. J Immunol 194: 1996–2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, K and Yamanaka, S (2006). Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 126: 663–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, K, Tanabe, K, Ohnuki, M, Narita, M, Ichisaka, T, Tomoda, K et al. (2007). Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell 131: 861–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusa, K, Rashid, ST, Strick-Marchand, H, Varela, I, Liu, PQ, Paschon, DE et al. (2011). Targeted gene correction of α1-antitrypsin deficiency in induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature 478: 391–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thatava, T, Armstrong, AS, De Lamo, JG, Edukulla, R, Khan, YK, Sakuma, T et al. (2011). Successful disease-specific induced pluripotent stem cell generation from patients with kidney transplantation. Stem Cell Res Ther 2: 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna, J, Wernig, M, Markoulaki, S, Sun, CW, Meissner, A, Cassady, JP et al. (2007). Treatment of sickle cell anemia mouse model with iPS cells generated from autologous skin. Science 318: 1920–1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolar, J, Xia, L, Riddle, MJ, Lees, CJ, Eide, CR, McElmurry, RT et al. (2011). Induced pluripotent stem cells from individuals with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. J Invest Dermatol 131: 848–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolar, J, Xia, L, Lees, CJ, Riddle, M, McElroy, A, Keene, DR et al. (2013). Keratinocytes from induced pluripotent stem cells in junctional epidermolysis bullosa. J Invest Dermatol 133: 562–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasmooij, AM, Garcia, M, Escamez, MJ, Nijenhuis, AM, Azon, A, Cuadrado-Corrales, N et al. (2010). Revertant mosaicism due to a second-site mutation in COL7A1 in a patient with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. J Invest Dermatol 130: 2407–2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almaani, N, Nagy, N, Liu, L, Dopping-Hepenstal, PJ, Lai-Cheong, JE, Clements, SE et al. (2010). Revertant mosaicism in recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. J Invest Dermatol 130: 1937–1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gostyński, A, Pasmooij, AM and Jonkman, MF (2014). Successful therapeutic transplantation of revertant skin in epidermolysis bullosa. J Am Acad Dermatol 70: 98–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gostyński, A, Llames, S, García, M, Escamez, MJ, Martinez-Santamaria, L, Nijenhuis, M et al. (2014). Long-term survival of type XVII collagen revertant cells in an animal model of revertant cell therapy. J Invest Dermatol 134: 571–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasmooij, AM, Jonkman, MF and Uitto, J (2012). Revertant mosaicism in heritable skin diseases: mechanisms of natural gene therapy. Discov Med 14: 167–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolar, J, McGrath, JA, Xia, L, Riddle, MJ, Lees, CJ, Eide, C et al. (2014). Patient-specific naturally gene-reverted induced pluripotent stem cells in recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. J Invest Dermatol 134: 1246–1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umegaki-Arao, N, Pasmooij, AM, Itoh, M, Cerise, JE, Guo, Z, Levy, B et al. (2014). Induced pluripotent stem cells from human revertant keratinocytes for the treatment of epidermolysis bullosa. Sci Transl Med 6: 264ra164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh, M, Kiuru, M, Cairo, MS and Christiano, AM (2011). Generation of keratinocytes from normal and recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa-induced pluripotent stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 8797–8802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh, M, Umegaki-Arao, N, Guo, Z, Liu, L, Higgins, CA and Christiano, AM (2013). Generation of 3D skin equivalents fully reconstituted from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). PLoS One 8: e77673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uitto, J, Christiano, AM, McLean, WH and McGrath, JA (2012). Novel molecular therapies for heritable skin disorders. J Invest Dermatol 132(3 Pt 2): 820–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogut, I, Roop, DR and Bilousova, G (2014). Differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells into a keratinocyte lineage. Methods Mol Biol 1195: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel, D, Bayerl, J, Nyström, A, Bruckner-Tuderman, L, Meixner, A and Penninger, JM (2014). Genetically corrected iPSCs as cell therapy for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Sci Transl Med 6: 264ra165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snippert, HJ, Haegebarth, A, Kasper, M, Jaks, V, van Es, JH, Barker, N et al. (2010). Lgr6 marks stem cells in the hair follicle that generate all cell lineages of the skin. Science 327: 1385–1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R, Zheng, Y, Burrows, M, Liu, S, Wei, Z, Nace, A et al. (2014). Generation of folliculogenic human epithelial stem cells from induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Commun 5: 3071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, DS, Hanson, ET, Lewis, RL, Auerbach, R and Thomson, JA (2001). Hematopoietic colony-forming cells derived from human embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 10716–10721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyba, M and Daley, GQ (2003). Hematopoiesis from embryonic stem cells: lessons from and for ontogeny. Exp Hematol 31: 994–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller, AM and Dzierzak, EA (1993). ES cells have only a limited lymphopoietic potential after adoptive transfer into mouse recipients. Development 118: 1343–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zambidis, ET, Peault, B, Park, TS, Bunz, F and Civin, CI (2005). Hematopoietic differentiation of human embryonic stem cells progresses through sequential hematoendothelial, primitive, and definitive stages resembling human yolk sac development. Blood 106: 860–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slukvin, II (2013). Hematopoietic specification from human pluripotent stem cells: current advances and challenges toward de novo generation of hematopoietic stem cells. Blood 122: 4035–4046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amabile, G, Welner, RS, Nombela-Arrieta, C, D'Alise, AM, Di Ruscio, A, Ebralidze, AK et al. (2013). In vivo generation of transplantable human hematopoietic cells from induced pluripotent stem cells. Blood 121: 1255–1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, N, Yamazaki, S, Yamaguchi, T, Okabe, M, Masaki, H, Takaki, S et al. (2013). Generation of engraftable hematopoietic stem cells from induced pluripotent stem cells by way of teratoma formation. Mol Ther 21: 1424–1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boitano, AE, Wang, J, Romeo, R, Bouchez, LC, Parker, AE, Sutton, SE et al. (2010). Aryl hydrocarbon receptor antagonists promote the expansion of human hematopoietic stem cells. Science 329: 1345–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, M, Awong, G, Sturgeon, CM, Ditadi, A, LaMotte-Mohs, R, Zúñiga-Pflücker, JC et al. (2012). T lymphocyte potential marks the emergence of definitive hematopoietic progenitors in human pluripotent stem cell differentiation cultures. Cell Rep 2: 1722–1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturgeon, CM, Ditadi, A, Awong, G, Kennedy, M and Keller, G (2014). Wnt signaling controls the specification of definitive and primitive hematopoiesis from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol 32: 554–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fares, I, Chagraoui, J, Gareau, Y, Gingras, S, Ruel, R, Mayotte, N et al. (2014). Cord blood expansion. Pyrimidoindole derivatives are agonists of human hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal. Science 345: 1509–1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gori, JL, Chandrasekaran, D, Kowalski, JP, Adair, JE, Beard, BC, D'Souza, SL et al. (2012). Efficient generation, purification, and expansion of CD34(+) hematopoietic progenitor cells from nonhuman primate-induced pluripotent stem cells. Blood 120: e35–e44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, VM, Lis, R, Liu, Y, Kedem, A, James, D, Elemento, O et al. (2014). Reprogramming human endothelial cells to haematopoietic cells requires vascular induction. Nature 511: 312–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddell, J, Gazit, R, Garrison, BS, Guo, G, Saadatpour, A, Mandal, PK et al. (2014). Reprogramming committed murine blood cells to induced hematopoietic stem cells with defined factors. Cell 157: 549–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, CF, Chang, B, Qiu, J, Niu, X, Papatsenko, D, Hendry, CE et al. (2013). Induction of a hemogenic program in mouse fibroblasts. Cell Stem Cell 13: 205–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi, P and Hematti, P (2008). Derivation and immunological characterization of mesenchymal stromal cells from human embryonic stem cells. Exp Hematol 36: 350–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenloh, W, Kambal, A, Sondergaard, C, McGee, J, Nacey, C, Kalomoiris, S et al. (2011). Characterization and in vivo testing of mesenchymal stem cells derived from human embryonic stem cells. Tissue Eng Part A 17: 1517–1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q, Gregory, CA, Lee, RH, Reger, RL, Qin, L, Hai, B et al. (2015). MSCs derived from iPSCs with a modified protocol are tumor-tropic but have much less potential to promote tumors than bone marrow MSCs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: 530–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters, C, Balthazor, M, Shapiro, EG, King, RJ, Kollman, C, Hegland, JD et al. (1996). Outcome of unrelated donor bone marrow transplantation in 40 children with Hurler syndrome. Blood 87: 4894–4902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, SM, Khan, S, Wagner, JE, Arthur, DC, Auerbach, AD, Ramsay, NK et al. (1996). Unrelated donor bone marrow transplantation for Fanconi anemia. Bone Marrow Transplant 17: 43–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz, AC, Orchard, PJ, Baker, KS, Giller, RH, Savage, SA, Alter, BP et al. (2011). Disease-specific hematopoietic cell transplantation: nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen for dyskeratosis congenita. Bone Marrow Transplant 46: 98–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolar, J, Bonfim, C, Grewal, S and Orchard, P (2006). Engraftment and survival following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for osteopetrosis using a reduced intensity conditioning regimen. Bone Marrow Transplant 38: 783–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Nasa, G, Caocci, G, Efficace, F, Dessì, C, Vacca, A, Piras, E et al. (2013). Long-term health-related quality of life evaluated more than 20 years after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for thalassemia. Blood 122: 2262–2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peffault de Latour, R, Porcher, R, Dalle, JH, Aljurf, M, Korthof, ET, Svahn, J et al. (2013). Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in Fanconi anemia: the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation experience. Blood 122: 4279–4286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan, ML and Wagner, JE (2010). Haematopoeitic cell transplantation for Fanconi anaemia - when and how? Br J Haematol 149: 14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boelens, JJ, Aldenhoven, M, Purtill, D, Ruggeri, A, Defor, T, Wynn, R et al.; Eurocord; Inborn Errors Working Party of European Blood and Marrow Transplant group; Duke University Blood and Marrow Transplantation Program; Centre for International Blood and Marrow Research. (2013). Outcomes of transplantation using various hematopoietic cell sources in children with Hurler syndrome after myeloablative conditioning. Blood 121: 3981–3987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titeux, M, Pendaries, V, Zanta-Boussif, MA, Décha, A, Pironon, N, Tonasso, L et al. (2010). SIN retroviral vectors expressing COL7A1 under human promoters for ex vivo gene therapy of recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Mol Ther 18: 1509–1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavilio, F, Pellegrini, G, Ferrari, S, Di Nunzio, F, Di Iorio, E, Recchia, A et al. (2006). Correction of junctional epidermolysis bullosa by transplantation of genetically modified epidermal stem cells. Nat Med 12: 1397–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murauer, EM, Gache, Y, Gratz, IK, Klausegger, A, Muss, W, Gruber, C et al. (2011). Functional correction of type VII collagen expression in dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. J Invest Dermatol 131: 74–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Urda, S, Lin, Q, Yant, SR, Keene, D, Kay, MA and Khavari, PA (2003). Sustainable correction of junctional epidermolysis bullosa via transposon-mediated nonviral gene transfer. Gene Ther 10: 1099–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Rosa, L, Carulli, S, Cocchiarella, F, Quaglino, D, Enzo, E, Franchini, E et al. (2014). Long-term stability and safety of transgenic cultured epidermal stem cells in gene therapy of junctional epidermolysis bullosa. Stem Cell Reports 2: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartier, N, Hacein-Bey-Abina, S, Bartholomae, CC, Veres, G, Schmidt, M, Kutschera, I et al. (2009). Hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy with a lentiviral vector in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Science 326: 818–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiuti, A, Biasco, L, Scaramuzza, S, Ferrua, F, Cicalese, MP, Baricordi, C et al. (2013). Lentiviral hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy in patients with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. Science 341: 1233151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biffi, A, Montini, E, Lorioli, L, Cesani, M, Fumagalli, F, Plati, T et al. (2013). Lentiviral hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy benefits metachromatic leukodystrophy. Science 341: 1233158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacein-Bey-Abina, S, Pai, SY, Gaspar, HB, Armant, M, Berry, CC, Blanche, S et al. (2014). A modified γ-retrovirus vector for X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency. N Engl J Med 371: 1407–1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacein-Bey-Abina, S, Garrigue, A, Wang, GP, Soulier, J, Lim, A, Morillon, E et al. (2008). Insertional oncogenesis in 4 patients after retrovirus-mediated gene therapy of SCID-X1. J Clin Invest 118: 3132–3142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Küttner, V, Mack, C, Rigbolt, KT, Kern, JS, Schilling, O, Busch, H et al. (2013). Global remodelling of cellular microenvironment due to loss of collagen VII. Mol Syst Biol 9: 657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo, SP, Lisowski, L, Bashkirova, E, Zhen, HH, Chu, K, Keene, DR et al. (2014). Somatic correction of junctional epidermolysis bullosa by a highly recombinogenic AAV variant. Mol Ther 22: 725–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porteus, MH and Baltimore, D (2003). Chimeric nucleases stimulate gene targeting in human cells. Science 300: 763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urnov, FD, Miller, JC, Lee, YL, Beausejour, CM, Rock, JM, Augustus, S et al. (2005). Highly efficient endogenous human gene correction using designed zinc-finger nucleases. Nature 435: 646–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, CJ and Bouhassira, EE (2012). Zinc-finger nuclease-mediated correction of α-thalassemia in iPS cells. Blood 120: 3906–3914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn, MJ, Starker, CG, McElroy, AN, Webber, BR, Riddle, MJ, Xia, L et al. (2013). TALEN-based gene correction for epidermolysis bullosa. Mol Ther 21: 1151–1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese, P, Schiroli, G, Escobar, G, Di Tomaso, T, Firrito, C, Calabria, A et al. (2014). Targeted genome editing in human repopulating haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 510: 235–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mali, P, Yang, L, Esvelt, KM, Aach, J, Guell, M, DiCarlo, JE et al. (2013). RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science 339: 823–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong, L, Ran, FA, Cox, D, Lin, S, Barretto, R, Habib, N et al. (2013). Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 339: 819–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H, Yang, H, Shivalila, CS, Dawlaty, MM, Cheng, AW, Zhang, F et al. (2013). One-step generation of mice carrying mutations in multiple genes by CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering. Cell 153: 910–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastiano, V, Zhen, HH, Haddad, B, Derafshi, BH, Bashkirova, E, Melo, SP et al. (2014). Human COL7A1-corrected induced pluripotent stem cells for the treatment of recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Sci Transl Med 6: 264ra163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolar, J and Wagner, JE (2015). A biologic Velcro patch. N Engl J Med 372: 382–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathes, DW, Chang, J, Hwang, B, Graves, SS, Storer, BE, Butts-Miwongtum, T et al. (2014). Simultaneous transplantation of hematopoietic stem cells and a vascularized composite allograft leads to tolerance. Transplantation 98: 131–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini, G, Rama, P, Mavilio, F and De Luca, M (2009). Epithelial stem cells in corneal regeneration and epidermal gene therapy. J Pathol 217: 217–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, W, Hayashida, Y, Chen, YT and Tseng, SC (2007). Niche regulation of corneal epithelial stem cells at the limbus. Cell Res 17: 26–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remington, J, Wang, X, Hou, Y, Zhou, H, Burnett, J, Muirhead, T et al. (2009). Injection of recombinant human type VII collagen corrects the disease phenotype in a murine model of dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Mol Ther 17: 26–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodley, DT, Keene, DR, Atha, T, Huang, Y, Lipman, K, Li, W et al. (2004). Injection of recombinant human type VII collagen restores collagen function in dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Nat Med 10: 693–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodley, DT, Wang, X, Amir, M, Hwang, B, Remington, J, Hou, Y et al. (2013). Intravenously injected recombinant human type VII collagen homes to skin wounds and restores skin integrity of dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. J Invest Dermatol 133: 1910–1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogan, J, Weinstein, J, Wang, X, Hou, Y, Martin, S, South, AP et al. (2014). Aminoglycosides restore full-length type VII collagen by overcoming premature termination codons: therapeutic implications for dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Mol Ther 22: 1741–1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Q, Wesson, RN, Maeda, H, Wang, Y, Cui, Z, Liu, JO et al. (2014). Pharmacological mobilization of endogenous stem cells significantly promotes skin regeneration after full-thickness excision: the synergistic activity of AMD3100 and tacrolimus. J Invest Dermatol 134: 2458–2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]