Abstract

Using in silico analysis of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), we identified microRNAs associated with glioblastoma (GBM) survival, and predicted their functions in glioma growth and progression. Inhibition of two “risky” miRNAs, miR-148a and miR-31, in orthotopic xenograft GBM mouse models suppressed tumor growth and thereby prolonged animal survival. Intracranial tumors treated with uncomplexed miR-148a and miR-31 antagomirs exhibited reduced proliferation, stem cell depletion, and normalized tumor vasculature. Growth-promoting functions of these two miRNAs were, in part, mediated by the common target, the factor inhibiting hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (FIH1), and the downstream pathways involving hypoxia-inducible factor HIF1α and Notch signaling. Therefore, miR-31 and miR-148a regulate glioma growth by maintaining tumor stem cells and their niche, and providing the tumor a way to activate angiogenesis even in a normoxic environment. This is the first study that demonstrates intratumoral uptake and growth-inhibiting effects of uncomplexed antagomirs in orthotopic glioma.

Introduction

Since the discovery of the first oncogenic miRNAs involved in cancer,1,2,3 critical functions of miRNA in dysregulated gene expression underlying human malignancies have been well established.4 The sequence-specific targeting of growth-promoting miRNAs emerges as a new and promising therapeutic strategy in oncology, following the recent success of the first miRNA-based human clinical trials.5 Others and we have previously identified two onco-miRNAs, miR-21 and miR-10b, as strongly elevated in glioblastoma, the most common malignant brain tumors in adults.1,6,7 Each of these miRNAs downregulates a number of tumor suppressor genes, and their knockdown in glioma cells results in activation of proapoptotic genes, and suppresses cell cycle and invasiveness.7,8,9 Identification of miR-296, a regulator of glioma-induced angiogenesis,10 further supported the diverse roles of miRNAs in various aspects of gliomagenesis. More recently, miRNAs have been implicated as important regulators of glioblastoma stem cell (GSC) maintenance, epigenetic pathways, metabolism, and invasiveness.11 Of note, however, is that none of these miRNAs is significantly associated with survival, suggesting that their targeting may be insufficient as a therapeutic strategy for gliomas.

Dysregulated miRNAs are considered to be essential players in carcinogenesis, and thus are potential therapeutic targets. Most previous screens, therefore, were primarily based on differential expression analyses. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) now enables us to apply a principally different in silico approach for identifying tumor-promoting miRNAs, and predicting the cellular pathways that they may regulate. In this work, we identified two risky miRNAs, miR-148a and miR-31, strongly associated with shortened GBM patient survival and with many biological functions promoting glioma growth. Using orthotopic xenograft models of GBM, we demonstrate that delivery of specific antagomirs to established GBM and the resulting suppression of these miRNAs reduce tumor growth and extend survival. We identify FIH1 as the common direct target of miR-148a and miR-31 that mediates their effects on HIF1α and Notch pathways and, thereby, regulates stem cells and angiogenesis in GBM.

Results

Identification of miRNAs associated with glioma survival

To discover critical miRNA regulators of gliomagenesis, we first identified those associated with glioma patient survival. Previous attempts to associate miRNA expression with GBM survival have been made based on the first release of the GBM TCGA data.12,13 We considered the 5-year survival of an expanded, more recent and divergent TCGA dataset consisting of 240 filtered GBM patients and 98 filtered low-grade glioma (LGG) patients. For each cancer type, we used an iterative approach to classify patients into low and high expression groups for each miRNA. We evaluated the relative survival of the low and high expression groups for each miRNA via the log-rank test, then used Cox proportional hazards regression to classify miRNAs as risky or protective, stratifying on patient age at diagnosis in both analyses. From 534 miRNAs considered in GBM, 25 showed association with survival (Figure 1a; adjusted log-rank P value < 0.03). Sixty-three of 378 miRNAs considered exhibited association with survival in LGG (Supplementary Table S2). Notably, only several common risky (including miR-221/222, miR-135b, and miR-148a) and one protective (miR-9) miRNA have been identified for both GBM and LGG (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 and Figure S1).

Figure 1.

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) analysis: identification of miRNAs associated with survival in glioblastoma (GBM), and related biofunctions. (a) Cox regression and Kaplan-Meier analysis of the GBM low and high miRNA expression groups from TCGA. (b) Five-year survival of patients in the miR-31 and miR-148a high and low expression groups from the GBM dataset, adjusted for patient age. Log-rank P value for miR-31 is 2.27e-5 and for miR-148a is 1.34e-3. (c) Relative expression of miR-148a and miR-31 in non-neoplastic controls, LGG, and GBM patients. (d) Pathway-level enrichment of various bioterms among the mRNAs correlating with miR-31 or miR-148a in GBM. Significantly correlated or anti-correlated genes (P < 0.0001) were assessed for enrichment of specific bioterms using multiple resources (KEGG, Biocarta, GO Biological Processes, and MSigDB). The bioterms overlapping for miR-148a and miR-31 are highlighted in red.

We next asked whether miRNAs significantly associated with survival may represent critical regulators of gene expression that actively modulate tumor growth or host response. Our previous work indicated that integrated miRNA and mRNA analysis might suggest potential biological functions for a miRNA regulator.7 We correlated miRNA expression for a subset of survival-associated miRNAs with mRNA expression of ~18,000 genes, using the GBM TCGA database. The lists of mRNAs correlating with selected miRNAs were further analyzed for pathway enrichment patterns using Gene Ontology and GSEA databases. The regulatory functions of several survival-associated miRNAs have been previously reported, allowing us to validate the predictive power of our approach. For example, the risky miR-221/222 family that correlates in GBM TCGA with proliferation, anti-apoptosis, and cell migration-related bioterms (Supplementary Figure S2) has been characterized as an oncogenic cluster that confers therapy resistance and promotes glioma cell invasion and survival.14,15,16,17 A protective miR-9 that correlates with neuroglial differentiation related bioterms (Supplementary Figure S2) is suppressed by mutant EGFR signaling and known to play a tumor-suppressor role in GBM.18

From the list of the top-ranked high-risk miRNAs (Figure 1a), we selected two molecules, miR-148a and miR-31 (Figure 1b), both practically unexplored in the GBM context. While each demonstrated highly diverse levels in GBM, their expression distributions were vastly different. MiR-148a was elevated in the majority of GBM specimens, whereas miR-31 was often downregulated relative to the normal brain tissues (Figure 1c). Nevertheless, they demonstrated overlapping correlation patterns with mRNA bioterms (Figure 1d). Specifically, both miRNAs correlated in TCGA with endothelial cell growth, wound healing, response to external stimulus, and H-Ras oncogene bioterms. In addition, miR-31 expression correlated with proliferation and immune response-related genes, and anticorrelated with glial differentiation, whereas miR-148a correlated with antiapoptosis, extracellular matrix, and response to hypoxia genes and anticorrelated with neuronal differentiation. This bioinformatics analysis suggested complex regulatory functions for these miRNAs, associated not only with gene expression in tumor cells per se, but also in cells of the angiogenic niche and tumor microenvironment. We therefore hypothesized that, in gliomas expressing high levels of miR-148a or miR-31, inhibition of these miRNAs may reduce tumor growth and prolong survival. We also hypothesized that it might cause more pronounced effects in orthotopic GBM models in vivo than in cellular models lacking micro-environmental cues.

Modulation of miR-148a and miR-31 has minimal effect on cultured glioma cells

As the first step toward investigating the roles of miR-148a and miR-31 in gliomagenesis, we tested expression of miR-148a and miR-31 in a panel of glioma cell lines and low passage patient-derived GBM neurospheres. Similar to the high expression range observed in tumor specimens, cultured glioma cells also exhibited widely diverse expression (Figure 2a,b). Both miRNAs were also expressed in primary human brain microvascular endothelial cells, HBECs (Figure 2a,b). To further investigate the functions of miR-148a and miR-31 in glioma, we selected a panel of cell lines and tumor neurospheres that express high or moderate levels of both miRNAs, and utilized highly specific and potent antisense 2'-O-MOE-PO miRNA inhibitors (ASO).19 Liposome-based transfection of such antagomirs to LN229, LN382 and U251 glioma cells resulted in a 90% knockdown efficiency (Figure 2c). Suppressing miR-31 or miR-148a in GBM lines, tumor neurospheres, or human primary endothelial cells has not resulted in significant phenotypic changes, nor has it altered cell viability or metabolic activity up to 120 hours post-transfection (Figure 2d). Similarly, there was no effect on cell cycle progression or migration in a wound-healing assay (data not shown). In contrast, we have observed, a prominent effect on cell invasion in some, although not all, glioma lines tested (Figure 2e). Overexpression of miR-148a and miR-31 with corresponding synthetic mimics also has not altered the growth of glioma cell lines (Supplementary Figure S3).

Figure 2.

Effects of miR-31 and miR-148a inhibition in vitro. (a,b) Screening glioma cultures for expression of miR-31 (a) and miR-148a (b). Expression was analyzed by Taqman qRT-PCR and normalized to uniformly expressed miR-99a. Primary human brain endothelial cells (HBECs) are also included. (c) Knock-down of miR-31 or miR-148a in glioblastoma (GBM) with ASOs results in 80–90% reduced levels in all GBM lines tested. miRNA expression was analyzed by qRT-PCR 24 hours after transfections. Error bars depict standard deviation, and n = 3. *P < 0.001. (d) Silencing miR-31 or miR-148a does not affect glioma or HBEC cell viability, as determined by WST-1 assays. Error bar = SEM and n = 3. (e) Silencing miR-31 or miR-148a decreases invasion of specific glioma lines through matrigel. The number of invading cells was normalized to the number of cells migrated without matrigel. The cultures treated with either anti-miR-31 or anti-miR-148a were compared to control treatments. Lower panels show images of reduced U251 invasion after ASO treatment. Error bar = SEM and n = 5. *P < 0.05.

Reducing miR-148a and miR-31 in glioma xenograft models has strong effects on tumor growth and survival

In order to better understand the role of these two miRNAs in tumor growth, we employed two orthotopic GBM xenograft models. LN229 and MGG75 gliomas, expressing relatively high levels of both miR-148a and miR-31, have been selected. The cells, transduced with mCherry and Luciferase constructs, were injected into the deep white matter in nude mice, the tumor growth was monitored using the whole body bioimaging, and body weight and survival tracked. LN229 cells formed fast-growing tumors with relatively defined boundary, some infiltrating cells, and rarely detectable small hemorrhage areas or necrotic centers (Figure 3a, left panel). The second, slower-growing model is based on low-passage MGG75 cultures, grown as tumor neurospheres in serum-free media, and thereby better retaining initial genetic and tumorigenic properties.20 The MGG75 tumors were highly diffusive and invasive, with hemorrhagic rim and necrotic center (Figure 3a, right panels). The miR-148a or miR-31 were suppressed in the established tumors by stabilized 2'-α-flouro MOE-PS ASO.21 To ensure efficient and continuous local delivery of either miR-31 or miR-148a inhibitors to the intracranial tumors, and avoid repeated neurosurgeries, we used osmotic pumps (Figure 3b,c).

Figure 3.

The experimental procedure of continuous delivery of miRNA inhibitors to intracranial glioblastoma (GBM) xenografts. (a) H&E histology of the LN229 and MGG75 intracranial gliomas. LN229 forms solid tumors with relatively well-defined boundary, and rarely-seen small areas of hemorrhage (left panel). MGG75 is highly infiltrative with poorly-defined tumor boundary, small hemorrhage areas, and large necrotic core. The contralateral, uninjected striatal area is shown for comparison (lower panels). Scale bar = 150 µm. (b) The experimental design used for investigation of miR-31 and miR-148a in vivo. (c) The set-up used for long-term, local delivery of miRNA inhibitors to intracranial GBM.

We first examined the effects of knocking down miR-31 or miR-148a in the intracranial LN229. Since this is a very aggressive model, the uncomplexed ASOs were administered to the intracranial tumors starting from day 7 after cell implantation (15 μg daily), when the tumors reached a relative luciferase signal of about ~106 photons/sec and exhibited exponential growth. The osmotic delivery continued over four weeks. To verify the delivery of the antagomirs, LN229 brain tumors were excised, sectioned, and immunostained with an antibody that recognizes the phosphorothioate backbone of the oligonucleotides. The tumor cells showed strong immunoreactivity, indicating the uptake of ASOs by at least 95% of the cells (Figure 4a and Supplementary Figure S5). In addition, the qRT-PCR analysis of RNA extracted from the intracranial LN229 tumors demonstrated that miR-148a and miR-31 become almost undetectable after the corresponding treatments and, thus, validated the high efficacy of osmotic delivery (Figure 4a, right panels).

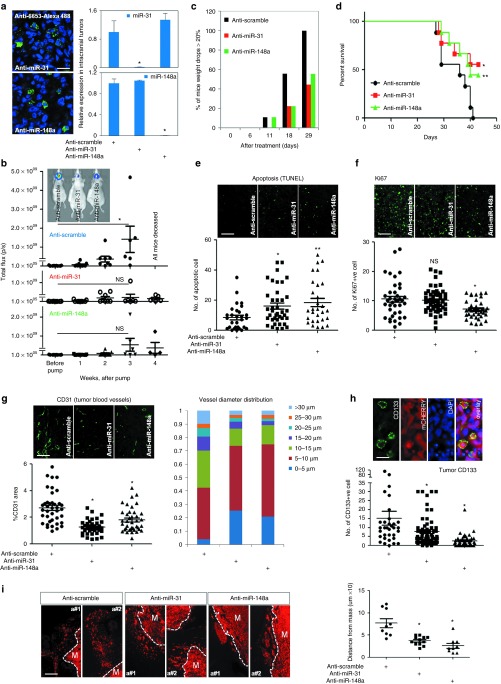

Figure 4.

Silencing miR-31 or miR-148a in intracranial LN229 tumors reduces tumor burden and extents animal survival. (a) The inhibitors are taken-up by tumor cells, resulting in reduced miR-148a/miR-31 levels. LN229 tumors are immunostained with the antibody detecting the intracellular ASOs (anti-6653, left panel, green). miR-31 or miR-148a expression is markedly diminished in the tumor, as detected by qRT-PCR. Results are normalized by the uniformly expressed miR-99a. Data are average from four to five animals. *P < 0.001. Scale bar = 50 µm. (b) Silencing miR-31 or miR-148a markedly reduces tumor burden. The tumor growth is monitored by luciferase imaging in vivo, and is expressed in photon flux per second. There are eight to nine animals per group at the treatment initiation, and each dot represents an animal/tumor. *P = 0.026; NS is not significant. The insert illustrates tumor imaging in representative animals, 28 days after treatment initiation. (c) Silencing miR-31 or miR-148a helps maintain the body weight in mice bearing intracranial tumors. N = 8–9 animals per group. (d) Silencing miR-31 or miR-148a significantly extends animal survival, analyzed by Kaplan-Meier plot. N = 8–9 animals per group. *P = 0.0279 and **P = 0.0483, by log-rank test. (e) Silencing miR-31 or miR-148a significantly increases tumor cell apoptosis. *P = 0.0062 and **P = 0.0024. Scale bar = 150 µm. Each dot represents one analyzed image. (f) Silencing miR-148a reduces tumor cell proliferation, as indicated by Ki67 proliferative marker. *P = 0.0025 and NS = not significant. Scale bar = 150 µm. (g) Silencing miR-31 or miR-148a normalizes tumor vasculature. Blocking miR-31 or miR-148a leads to the reduction of CD31 positive areas (left panels) and decreases tumor blood vessel diameter (right panel). Tumor vessels look smaller and less torturous. *P < 0.001. Scale bar = 150 µm. (h) Silencing miR-31 or miR-148a diminishes tumor cell self-renewal, as indicated by CD133 staining. Upper panels show the CD133-positive tumor cells. *P < 0.001. Scale bar = 25 µm. (i) Silencing miR-31 or miR-148a reduces tumor invasion. Two representative tumors are shown for each treatment group. The distance between infiltrating tumor cells and tumor mass (M) was measured in three tumors per group, three sites per tumor. Blocking either miRNA reduces the distance between infiltrative tumor cells and tumor mass. *P < 0.01.

Intratumoral inhibition of miR-31 or miR-148a led to pronounced beneficial effects for the animals bearing LN229 tumors (n = 8–9 per group). It markedly reduced the rate of tumor growth (Figure 4b). At least 50% of mice treated with the inhibitors of either miR-31 or miR-148a maintained healthy body weight, whereas the control group treated with a nontargeting oligonucleotide of the same chemistry lost their weight dramatically over the course of the study (Figure 4c). Correspondingly, the inhibition of either miR-31 or miR-148a led to a significant increase in median survival (log rank-test, control versus anti-miR-31, P = 0.0279; control versus anti-miR-148a, P = 0.0483) (Figure 4d). These results support the idea that high levels of either miR-31 or miR-148a contribute to glioma growth and shortened survival in GBM.

To explore the mechanism underlying the therapeutic effects of the miRNA inhibitors, at the end point of the study tumors were excised and analyzed (n = 4–5 tumors per group). Inhibition of either miR-148a or miR-31 had significant effects on tumor histopathology. First, it increased the number of apoptotic cells detected by TUNEL (Figure 4e). The number of cells labeled with Ki67, a marker of cell proliferation, was decreased by anti-miR-148a, but not by anti-miR-31 (Figure 4f). As “endothelial cells” bioterm was associated with both miR-148a and miR-31 in GBM TCGA (Figure 1d), and tumor angiogenesis is a critical factor modulating gliomagenesis, we further examined tumor angiogenesis in the LN229 tumors. There was a profound morphological difference between the CD31-stained large abnormal vessels characteristic for the control tumors, and normalized vessels resembling brain vasculature, observed in anti-miR-148a and anti-miR-31 groups. Total CD31-positive areas and vessel diameter distribution were dramatically altered (Figure 4g). Furthermore, blocking either miRNA also reduced the number of GSCs, as indicated by CD133 staining. In case of anti-miR-148a, CD133 positivity dropped almost by 60% (Figure 4h). Finally, we took advantage of the limited invasiveness of LN229 tumors to examine the migratory properties of the control and miRNA targeted groups. Quantitative analysis of cells migrating away from the tumor mass revealed that inhibition of miR-148a or miR-31 resulted in a 50–60% decrease in travel distance (Figure 4i), indicating that tumor cell invasiveness is reduced. Therefore, a number of key characteristics of GBM, including self-renewal and invasiveness of tumor cells, as well as tumor vascularization, have been modulated in the LN229 model by the specific miR-148a and miR-31 inhibitors.

The key characteristics of human high-grade glioma include its highly infiltrative nature and the presence of a GSC population that might be responsible for tumor formation, expansion, resilience, and recurrence.22,23 To validate our conclusions in an animal model that more closely recapitulates human pathology, we employed the MGG75 tumor neurosphere model that forms highly invasive and infiltrative intracranial GBM (Figure 3a). In cultures at least 90–95% of the MGG75 neurospheres were positive for neural stem cell markers nestin and SOX2 (data not shown). Small spheres were intracranially implanted and the experiments performed similarly to those described above for LN229, with the exception of treatment being initiated at 100 days postinjection, due to slower tumor engraftment and progression. As previously detected in the LN229 model, continuous inhibition of miR-31 or miR-148a also produced marked health beneficial effects in animals bearing MGG75 intracranial tumors (Figure 5). First, it suppressed tumor growth rate (Figure 5a). Second, while 90% of the animals treated with the control ASO lost at least 20% body weight and showed high morbidity or mortality, only 10 and 40% of anti-miR-31 and anti-miR-148a animals, respectively, showed some weight loss (Figure 5b). Consequently, animal survival was extended significantly (Figure 5c). To provide further insights into the delayed tumor growth and pathology, we stained and quantified the tumor sections for cell proliferation marker Ki67, the stem cell markers SOX2 and nestin, and tumor angiogenesis marker CD31. There was a significant reduction of Ki67, SOX2, and CD31 immunolabeling in the brain tumor sections of animals treated with anti-miR-31 or anti-miR-148a (Figure 5d,e,g). Though the reduction of nestin signal did not reach statistical significance, a decreasing trend was also observed (Figure 5f).

Figure 5.

Silencing miR-31 or miR-148a in intracranial MGG75 tumors reduces tumor burden and extents animal survival. (a) Continuous delivery of miRNA inhibitors over a period of 8 weeks significantly reduces MGG75 growth rate, as monitored by luciferase imaging. N = 8–9 mice per group. *P < 0.05 in all time points examined. (b) Silencing miR-31 or miR-148a helps maintain the body weight in mice bearing MGG75 tumors. N = 10–11 mice per group. (c) Silencing miR-31 or miR-148a significantly extends survival of MGG75-bearing mice, as analyzed by Kaplan-Meier plot. N = 10–11 mice per group. *P < 0.0001 and **P = 0.0251, by log-rank test. (d) Silencing miR-31 or miR-148a reduces tumor cell proliferation, as indicated by Ki67 proliferative marker. *P <0.0001. Scale bar = 150 µm. Each dot represents an analyzed image. (e) Silencing miR-31 or miR-148a markedly reduces percentage of SOX2-positive cells. *P < 0.0001. Scale bar = 150 µm. (f) Silencing miR-31 or miR-148a slightly reduces percentage of nestin-positive cells. NS, not significant. Scale bar = 150 µm. (g) Silencing miR-31 or miR-148a normalizes tumor vasculature. Blocking miR-31 or miR-148a reduces the percentage of abnormal blood vessels, and decreases tumor blood vessel diameter (data not shown). Tumor vessels look smaller and less torturous. *P < 0.01. Scale bar = 150 µm.

Human TCGA datasets and experiments with mouse orthotopic glioma xenografts support the idea that suppressing miR-31 and miR-148a activity could slow down glioma growth rate and extend survival. Remarkably, the in vivo consequences of inhibiting either miR-148a or miR-31 were surprisingly similar. The slower growth of tumors with suppressed miR-148a or miR-31 can be likely attributed to the reduced tumor cell proliferation (Ki67), number of GSCs (CD133/SOX2/NESTIN), and partly normalized tumor blood vessels. This led us to hypothesize that miR-31 and miR-148a may regulate common targets and downstream pathways in the GBM microenvironment. We, therefore, sought to identify common targets for miR-31 and miR-148a that could be involved in the self-renewal and angiongenesis-related phenotypes, observed in our experiments.

miR-148a and miR-31 target the factor inhibiting hypoxia (FIH1) to promote downstream HIF1α and Notch signaling

Computational algorithms predicted numerous putative targets for miR-31 and miR-148a, and some of them have important functions in angiogenesis and stem cell maintenance (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S3). We found that one of the targets potentially shared by miR-148a and miR-31, hypoxia inducing factor 1α inhibitor (HIF1AN) also known as the factor inhibiting hypoxia (FIH1; predicted by three out of five algorithms for miR-31, and by two algorithms for miR-148a), is indeed regulated by each of these miRNAs in glioma cells (Figure 6a). Other tested putative targets (PTEN, EGLN3, ACVR1, DICER1, AKAP7, BACH2, CUL5, NARG1, NFAT5, SLC24A3, and SULF1) were not regulated in glioma cells (data not shown). FIH1 is an asparaginyl hydroxylase that negatively regulates HIF1α stability and transcriptional activity in normoxic conditions; it is destabilized by hypoxia, which leads to HIF1α transcription and thereby upregulation of VEGF and angiogenesis.24,25 FIH1 also interacts with and hydroxylates Notch intracellular domain (NICD), and thereby represses NICD transcription that is critical for both angiogenesis and maintaining neural stem cell properties.26,27 Furthermore, HIF1α and Notch have been shown to interact in GBM, and HIF1α requires Notch pathway for the maintenance of GSCs.28 FIH1 therefore may represent a very attractive common target for miR-31 and -148a implicated in GBM.

Table 1. Common computationally predicted targets for both miR-148a and miR-31 that are associated with angiogenesis, cellular response to hypoxia, and stem cell (SC) maintenance bioterms.

Figure 6.

FIH1 as the common target of miR-148a and miR-31 that antagonizes hypoxia and Notch pathways. (a) FIH is derepressed in glioblastoma (GBM) lines and spheres upon suppression of either miR-31 or miR-148a, and HIF1α levels are reduced. n = 5; representative western blot images are shown. (b) Percentage of intracranial LN229 tumor cells immuno-positive for FIH1 is prominently increased. *P < 0.0001. Scale bar = 150 µm. Each dot represents an analyzed image. (c) Percentage of intracranial MGG75 tumor cells immuno-positive for FIH is prominently increased. *P = 0.0001 and **P < 0.0001. Scale bar = 150 µm. (d) Validation of direct binding and regulation of FIH1 mRNA by miR-148a, using luciferase constructs bearing either WT or mutated FIH1 3'UTR. The site 1 containing 11-mer binding motif, which mutations abolished the binding (mut 1, underlined), is shown in the upper panel. *P < 0.05 and NS is not significant. (e) miR-148 or miR-31 inhibition reduces expression of HIF1α and NICD downstream genes in LN229 cells, whereas FIH1 silencing abolishes these effects. Upper panels show mRNA levels of ENO1, VEGF, HES1 and HEY1, normalized by 18S rRNA. N = 4. *P < 0.05. NS, not significant. (f) Percentage of nuclear NICD is dramatically reduced upon miR-31 or miR-148a inhibition in intracranial LN229 tumors. *P = 0.0061 and **P = 0.0019. Scale bar = 25 µm; N = 6. (g) Median VEGF level is reduced upon miR-31 or miR-148a inhibition in intracranial LN229 tumors. *P < 0.05. Scale bar = 25 µm. (h) Inhibition of miR-31 or miR-148a in MGG75 cultures reduces the levels of secreted VEGF, as indicated by antibody arrays and Western blotting. *P < 0.05. (i) The media conditioned (CM) with glioma MGG75 cells transfected with anti-miR-148a, enhances endothelial cell degeneration. CM collected after silencing miR-148a was added to the tubules formed by HUVECs or HBECs, which enhanced endothelial cell degeneration within 16 hours. Quantification of branching length and junctions is shown on the lower panels. N = 4. *P < 0.05.

Inhibition of either miR-148a or miR-31 led to markedly increased FIH1 expression in GBM lines and MGG75 spheres (Figure 6a). It also dramatically reduced the levels of HIF1α, an autoregulating gene, in LN229 and LN382 lines, indicating that miR-31 and miR-148a regulated FIH1 functionally antagonizes with the HIF1α pathway. Importantly, inhibition of miR-148a and miR-31 in orthotopic LN229 and MGG75 tumors in vivo also strongly increased FIH1 levels (Figure 6b,c, respectively). The direct binding and regulation of FIH1 by miR-31 has been previously demonstrated.29,30 To validate that miR-148a also directly controls FIH1 expression, we cloned the predicted miR-148a binding sites within FIH1 3'UTR to a luciferase reporter, and observed that miR-148a regulated expression of this construct. The miR-148a-mediated modulation was abolished by a mutation within the binding site 1, indicating that miR-148a directly binds and represses FIH1 expression (Figure 6d).

To investigate the mechanism in more details and test if the levels of FIH1, elevated by miR-148a and miR-31 inhibitors, are indeed antagonizing both hypoxia and Notch pathway through HIF1α, we examined the mRNA levels of ENO1, VEGF, HES1, and HEY1, all direct transcriptional targets of HIF1α. VEGF is a prominent proangiogenic factor in the tumor microenvironment,31 and HES1 and HEY1 directly reflect Notch pathway activity essential for maintaining GSCs.32,33,34 Inhibition of miR-31 or miR-148a decreased the levels of ENO1, VEGF, HES1, and HEY1 mRNAs (Figure 6e), suggesting reduced HIF1α activity as well as Notch pathway activity. Silencing FIH1 expression in the same experimental setting by RNAi completely restored the reduced expression of all four mRNAs. These rescue experiments indicate that FIH1, the common target of both miR-31 and miR-148a, can mediate their functions associated with tumor angiogenesis and maintenance of GSCs, and implicate VEGF and Notch as the downstream effectors of miR-148a and miR-31 signaling.

To further investigate the effects of the miRNA inhibitors on Notch or VEGF pathway in in vivo GBM models, we examined the levels of nuclear NICD and VEGF in intracranial LN229 tumor sections. There was a significant decrease in nuclear NICD staining after inhibiting miR-31 or -148a (Figure 6f), and the median VEGF levels reduced by 50% (Figure 6g). There was also a small but significant reduction of VEGF levels in conditioned medium (CM) produced by MGG75 tumor cells after inhibition of miR-31 or miR-148a, as detected by either antibody array (Figure 6h upper panel) or Western blotting (Figure 6h lower panel). Consistent with this observation, exposing endothelial cell networks, formed by HUVECs or HBECs cells, to these media led to a faster degeneration of the vessels (Figure 6i). Marked reduction of vessel network junctions and branching was observed in cultures exposed to CM of anti-miR-148-treated glioma cells, but not those treated with anti-miR-31 (Figure 6i, graphs). Altogether, these data indicate that high levels of miR-31 or miR-148a promote glioma growth by downregulation of FIH1 and thereby enhancing HIF1α and Notch pathway activity, tumor angiogenesis, and tumor progenitor expansion even in the normoxic conditions (model in Figure 7).

Figure 7.

A model of miR-148a/miR-31/FIH1/HIF1α-Notch signaling in glioblastoma self-renewal and angiogenesis.

Discussion

The analysis of miRNA expression data in combination with mRNA bioterms in glioblastoma TCGA data identified miR-148a and miR-31 among a few highly significant “risky” miRNAs associated with shortened survival (see ref. 12 and Figure 1). MiR-148a levels were frequently elevated in both low-grade gliomas and GBM, whereas miR-31 was elevated only in a small proportion of GBM tumors. Nevertheless, each miRNA correlated strongly with the genes expressed in H-Ras activated cells, the genes involved in endothelial cell growth, and response to external stimuli. In addition, miR-148a correlated with hypoxia-induced and extracellular matrix genes, and miR-31 correlated with genes related to proliferation and immune response. This analysis (focused on associated biofunctions rather than predictions of direct targets) suggested a broad range of both autocrine and paracrine functions, regulated in the complex tumor microenvironment by these miRNAs, and possibly elicited by common targets and signaling pathways. We hypothesized that inhibition of miR-148a or miR-31 in gliomas exhibiting high levels of these molecules could reduce tumor growth and prolong survival, and addressed this hypothesis using two selected orthotopic mouse models bearing human GBM xenografts.

Sequence-specific inhibition of either miR-148a or miR-31 reduced tumor growth and vascularization. Most pronounced effects were observed on CD31+ vessels and CD133+/SOX2+ GSCs. The altered cross-talk between GSC and endothelial compartments may explain why reducing miR-148a or miR-31 in orthotopic glioma has strong impact on tumor growth and survival but minimal effects in cultured cells. These effects were associated with elevated FIH1, and reduced NICD and VEGF immunostaining. Our experiments demonstrate that FIH1 is the common direct target regulated to the same extent by miR-148a and miR-31, which mediates their effects on tumor growth by counteracting HIF1α and Notch signaling. FIH1 is the critical oxygen-dependent asparaginyl hydroxylase that suppresses transcriptional activity of HIF1α.24,25 Hypoxia inhibits FIH1 activity and reduces HIF1α hydroxylation, facilitating recruitment of transcriptional coactivators CBP/p300 and leading to the activation of HIF1α and upregulation of VEGF and other proangiogenic factors. In some glioma lines, miR-148a and miR-31 inhibitors altered not only HIF1α activity, but also its levels. Expression and activity of HIF-1α in cancer cells is regulated at the transcriptional, translational, and posttranslational level by multiple interacting molecular pathways. One possible explanation of HIF1α expression regulation is an autoregulatory nature of its transcriptional regulation.35 In addition, HIF1α stability is tightly controlled by proteasome-dependent degradation, and several components of the degradation machinery are additional putative targets of miR-148a or miR-31 (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S3). Furthermore, PI3K and Ras pathways can increase HIF1α expression by promoting its translation, and key factors belonging to these pathways could be directly regulated by either miR-148a or miR-31 (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S3). In addition, HIF-1α itself, HIF-2α/EPAS1, transcriptional coactivator p300, and several other transcription factors competing for p300 (e.g., CREB, FOXO3) are computationally predicated targets of one of these miRNAs. The contribution of those potential regulatory events and interactions to the miR-148a/31 function remains to be further investigated.

We observed no significant effects of miR-148a/31 on HIF2α/EPAS1 levels in glioma cells (data not shown). Although HIF1α and HIF2α have similar downstream targets and we cannot rule out the contribution of HIF2α, HIF1α appeared to be the major mediator in our system since 1) under normoxic conditions HIF1α is more responsive to the inhibitory effects of FIH1 than HIF2α,36 and 2) HIF1α is expressed in the majority of glioma cells whereas HIF2α expression is confined to a small population of GBM cells.37

FIH1 also hydroxylates and thereby negatively regulates transcriptional activity of NICD.26 Moreover, the HIF1α and Notch signaling pathways are coupled.27,28 In GBM, HIF1α interacts with and stabilizes NICD, and activation of Notch signaling is essential for expansion and maintenance of GSC. On the other side, the concordant regulation by FIH1, and crosstalk between HIF1α and Notch could lead to coupled responses of vascular and tumor progenitor compartments. Our experiments, performed in normoxic culture conditions and intracranial xenograft tumors with limited necrosis and hypoxia, suggest that high levels of miR-148a and miR-31 ensure an additional, oxygen-independent mechanism of suppressing FIH1 levels and activity, and subsequent activation of HIF1α and Notch signaling. In human GBM, characterized by variable levels of hypoxia, such regulation could contribute to hypoxia-independent propagation of tumor progenitors and induction of angiogenesis associated with glioma growth.

Although FIH1 emerged as the central factor mediating miR-148a and miR-31 regulation in GBM, additional FIH1/HIF-1α-independent mechanisms could also contribute to the observed phenotypes. Table 1 and Supplementary Table S3 present an overview of additional putative targets associated with angiogenesis and stem cell maintenance, as well as expression correlations they exhibit with miR-148a/31 in GBM TCGA. It must be noted that such correlation analysis should be interpreted with caution and used to neither assume nor rule out the direct regulation without additional experimental support. The tumor tissue analysis provides an end-stage snapshot of gene expression in a complex heterocellular specimen, and does not reflect the functional relationship between the correlating factors. This analysis indicates a significant inverse correlation for miR-148a/FIH1, but lack of such correlation for miR-31/FIH1 (Table 1 and Supplementary Figure S4); this is despite the experimentally validated regulation of FIH1 by both miRNAs. Many predicted targets exhibit positive correlations with miR-148/31 expression in GBM TCGA (e.g., NRP1, ITGA5, EFNB2). The evidence of direct positive regulation mediated by miRNAs in glioma cells is lacking, and such correlations can merely reflect indirect relationships. Nevertheless, it would be important to study the effects of miR-148/31 on the angiogenic factor Neuropilin-1 (NRP1) and other putative targets, test the possibility of unconventional positive regulation, and determine its impact in GBM.

While inhibition of the two miRNAs caused, overall, very similar effects on glioma in vitro and in vivo, some effects appeared distinct or cell type specific. For example, Ki67 proliferative marker was strongly reduced by both miRNA inhibitors in MGG75 tumors, but only by anti-miR-148a in LN229 tumors. Only CM of glioma cells treated with anti-miR-148a, but not with anti-miR-31, reduced endothelial tubule formation; this is despite strong effects on blood vessels caused by both inhibitors in orthotopic GBM in vivo. Additional targets, specific for either miR-31 or miR-148a, could mediate these effects. Of note, 18 targets associated with angiogenesis are predicted by at least two algorithms for miR-148a, and only 4 such targets for miR-31 (Supplementary Table S3). Among the putative targets requiring a more detailed analysis are, for example, miR-31-specific HBEGF, ELAVL1, and EGLN3, and miR-148a-specific EPAS1, EP300, and NF1.

Glioblastoma tumor tissue and cultured glioblastoma cells exhibit a wide range of miR-148a and miR-31 expression. Of note, each of these miRNAs is dysregulated in various cancers, and a number of studies suggest both tumor-promoting and tumor-suppressing roles for them.38,39,40,41 In GBM, high levels of these miRNAs have been associated with mesenchymal subtype derived from astrocytic precursors.13 Inverse correlation of miR-31 with glial differentiation, and of miR-148a with neuronal differentiation, observed in GBM TCGA (Figure 1d) suggests that distinct populations of cancer-initiating cells may contribute to high levels of these miRNAs. Interestingly, miR-148a is regulated by DNA methylation in IDH-dependent or independent way,42 and it also directly targets DNA methyltransferase 1,43 being thereby involved in a feedback mechanism controlling DNA methylation. miR-31 is mapped to chromosome 9p21.3, a region of genomic instability that is frequently lost in GBM, which also encodes tumor-suppressor genes CDKN2A and CDKN2B.40 Although this location could explain the downregulation of miR-31 frequently observed in GBM, what factors define its high expression in a subset of gliomas (thereby establishing a strong risk factor) and whether its loss is a part of the endogenous growth-constraining mechanism remain to be investigated. The lack of miR-31 expression in many samples may also partly explain why no correlation is observed between miR-31 and FIH1 levels in GBM TCGA.

Finally, we have utilized the continuous osmotic delivery of uncomplexed 2'-α-flouro MOE-PS miRNA inhibitors to intracranial brain tumors. Of note, glioma cells are highly proliferative, and substantial levels of miRNAs in these cells are usually ensured by their active transcription. In presence of transcription inhibitor actinomycin D, the half-life of miR-148a and miR-31 in glioma cells is around a few hours (Supplementary Figure S6). We have chosen osmotic delivery in order to overcome the dilution of ASO in growing GBM, avoid multiple intracranial injections, and follow a singe clinical trial with similar antisense inhibitors of TGFβ.44 This method provides continuous, local, and targeted intratumoral infusion of the ASO to intracranial GBM, and may also represent highly efficient therapeutic approach for malignant brain tumors. To the best of our knowledge, this work offers the first indication that uncomplexed antagomirs can be efficiently taken-up by glioma, inhibit a miRNA, and lead to target derepression in intracranial gliomas. The effective and safe dose of 15 μg/daily was within the range previously utilized for mRNA targeting by similar ASOs,45,46 whereas 60 μg/daily appeared slightly toxic (data not shown). While the goal of this study was to investigate miR-148a and miR-31 functions in GBM in vivo rather than to optimize a therapeutic miRNA inhibition, our data suggest that suppression of these miRNAs might be beneficial for a subset of gliomas expressing them at high levels. Of note, a recent report indicates that miR-148a overexpression may reduce cell viability in IDH mutant glioma42; that work, however, utilized stable lentiviral overexpression, which admittedly resulted in supraphysiological (>100-fold) elevation of miR-148a. Further research is required to address the therapeutic potential of modulating miR-31 and miR-148a in GBM.

Materials and Methods

TCGA analysis and target predictions. The level 3 TCGA miRNA and mRNA expression data (either microarray or RNAseq) and metadata including survival information for GBM and LGG patients were downloaded from the NCI TCGA data portal (https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga/). The data were processed, normalized, matched, and analyzed with customized R scripts (www.r-project.org). The lists of mRNAs correlated with miR-148a and miR-31 were analyzed for pathway enrichment patterns using in-house tool PPEP analysis pipeline47 using KEGG (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/), Biocarta (http://www.biocarta.com/), Gene Ontology database (GO, http://www.geneontology.org), and MSigDB (http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp) as previously described.7,48 For survival analysis, only patients with a tumor sample containing >90% of cancer cells and <40% necrosis were included. For each miRNA, a series of cutoffs was tested to find the optimal partitioning of patients into low and high expression groups with distinct survival, measured via the log-rank test. For the log-rank tests and Cox proportional hazards analysis, patients were stratified based on the median age at initial pathologic diagnosis for each dataset. miRNA expression was treated as a binary variable, equivalent to the classification of patients into the low- and high-expression groups.

Computational predictions of miRNA targets were based on five different algorithms, and included TargetScan, PicTar, RNA22, PITA, and miRanda, as retrieved from StarBase (http://starbase.sysu.edu.cn/).49

Cell cultures and transfections. Glioma cell lines were maintained in 1× Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). MGG75 neurospheres were isolated from a surgical specimen of glioblastoma as described in ref. 20 and maintained in Neurobasal medium supplemented with B27, N2, FGF-2 (20 ng/ml), EGF (20 ng/ml), and 2 μg/ml heparin. Transfections of siRNA, miRNA precursors, or inhibitors were performed with Lipofectamine 2000, at 50 nmol/l final concentration. The 2'-O-methoxyethyl (2'-O-MOE-PO) antisense inhibitors (Regulus Therapeutics) have been used for in vitro experiments.

RNA isolation, qRT-PCR, and protein analysis by western blotting were performed as previously described.50 Examination of secreted angiogenic factors in conditioned media was performed using Human angiogenesis Antibody Array (R&D, Minneapolis, MN; ARY007) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Spots intensities were quantified with ImageJ software.

Cell viability, tumor cell invasion, and apoptosis have been assessed using WST1, matrigel invasion, and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assays, correspondingly, as previously reported.50

Luciferase reporter assay. A fragment of FIH 3' UTR (1632–2703 nt) was cloned into psiCHECK2 (Promega, Madison, WI) downstream of renilla luciferase, and mutations were introduced using QuikChange Multi Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA; 200514). For primer sequences please refer to the Supplementary Table S4. LN229 cells were cotransfected with 200 ng psiCHECK-2 luciferase reporter containing 3′-UTR variants and either control or anti-miR-148a oligonucleotides at 50 nmol/l concentration. Three days later, luciferase luminescence was measured with Dual-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega E2920).

Stereotaxic injection of tumor cells, whole body imaging, and osmotic delivery of miRNA inhibitors. Tumor cells or small spheres expressing firefly luciferase and mCherry were implanted into the striatal area (coordinates: P-A 0.5; C-L 1.7; D-V 2.3 mm) of 8 weeks old nude mice and the growth of intracranial tumors was monitored by Fluc bioluminescence as described.51 When bioluminescence reached the exponential phase, ALZET Osmotic infusion pumps (model 2004; Cupertino, CA; 28 days) and a micro-infusion cannula (Alzet brain infustion kit 3) for controlled intraventricular delivery of antagomirs were stereotactically inserted at the same coordinates. 2'-alpha-flouro MOE ASOs with phosphorothioate backbone (provided by Regulus Therapeutics) were infused at 15 µg daily (0.25 µl/hour). All animal studies, including animal survival experiments, have been approved by the Harvard Medical Area Standing Committee on Animals.

Immunohistochemistry. Intracranial tumors were fixed with 4% formaldehyde, embedded, frozen, and sectioned. Staining of 10µm-thick sections was performed using CD31 (Chemicon, Temecula, CA; MAB1398Z), Ki67 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA; 15580), SOX2 (CST, Danvers, MA; 3579), NESTIN (Abcam 105389), FIH (Abcam 92498), NICD (Millipore, Billerica, MA 07-1232), CD133 (Abcam 19898) or 6653 (Regulus) antibodies, followed by visualization using confocal microscopy as previously reported.51 Immunoreactivity was quantified using ImageJ, and VEGF quantified by mean gray levels using the histogram function. The diameters of blood vessels were measured using the Zen Black software (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY).

Tube formation assay. MGG75 (3 × 105 cells) were transfected with anti-miR-31 or anti-miR-148a in complete medium for one day, and incubated with basal medium for additional 3 days. The cell-free conditioned medium was used to resuspend 2.4 × 104 HUVECs or HBECs, and seed them on growth factor reduced Matrigel-coated 48-well plate or ibidi angiogenesis slide. The structure and morphology of three dimensional endothelial tubes were examined 16–24 hours after incubation. Multiple parameters of the endothelial tubes were measured by angiogenesis plugin available from ImageJ/NIH.

Statistical analysis and image quantification. We used the unpaired, two-tailed student's t-test for comparison between two samples. For survival rate we plotted the survival distribution curve with the Kaplan-Meier method followed by log-rank testing (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). We quantified all images using Image J (NIH). Please refer to http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/docs/guide/146-30.html for detailed method of image analyses. “Mean gray value” is defined as the sum of the gray values of all the pixels in each image divided by the number of pixels. All values were presented as mean ± SEM.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Table S1. Risky or protective miRNAs in GBM, identified by log-rank tests and Cox proportional hazards analysis. Table S2. Risky or protective miRNAs in LGG, identified by log-rank tests and Cox proportional hazards analysis. Table S3. Predicted targets specific for either miR-148a and miR-31 and associated with angiogenesis, cellular response to hypoxia, and stem cell maintenance bioterms. Table S4. Primers used to clone the wildtype FIH1 3'UTR, and introduce mutations within the miR-148a putative binding sites. Figure S1. The 5-year survival of patients in the miR-148a high and low expression groups from the LGG dataset, adjusted for patient age. Figure S2. Pathway-level enrichment of various bioterms among the mRNAs correlating with miR-222 or miR-9 in GBM. Figure S3. Overexpression of miR-31 or miR-148a with mimic molecules does not alter GBM cell viability, as assessed by WST-1 assay. Figure S4. Correlation of FIH1 with miR-148a and miR-31 with TCGA GBM samples. Figure S5. LN229 tumors are immunostained with the antibody detecting the intracellular ASOs (upper panel, green; DAPI-lower panel). Figure S6. Half life of miR-148a and miR-31 in LN229 glioma cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from NIH/NCI (R01CA138734), Sontag Foundation Distinguished Scientist Award, National Brain Tumor Society, and Brain Science Foundation to AMK, and NIH/NCI R01CA163336 and Sontag Foundation Distinguished Scientist Award to J.S.S. We thank Regulus Therapeutics, Inc. for providing us with specific antagomirs. There is no potential conflict of interest

Supplementary Material

References

- Chan, JA, Krichevsky, AM and Kosik, KS (2005). MicroRNA-21 is an antiapoptotic factor in human glioblastoma cells. Cancer Res 65: 6029–6033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, L, Thomson, JM, Hemann, MT, Hernando-Monge, E, Mu, D, Goodson, S et al. (2005). A microRNA polycistron as a potential human oncogene. Nature 435: 828–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashita, Y, Osada, H, Tatematsu, Y, Yamada, H, Yanagisawa, K, Tomida, S et al. (2005). A polycistronic microRNA cluster, miR-17-92, is overexpressed in human lung cancers and enhances cell proliferation. Cancer Res 65: 9628–9632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iorio, MV and Croce, CM (2012). microRNA involvement in human cancer. Carcinogenesis 33: 1126–1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, HL, Reesink, HW, Lawitz, EJ, Zeuzem, S, Rodriguez-Torres, M, Patel, K et al. (2013). Treatment of HCV infection by targeting microRNA. N Engl J Med 368: 1685–1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasayama, T, Nishihara, M, Kondoh, T, Hosoda, K and Kohmura, E (2009). MicroRNA-10b is overexpressed in malignant glioma and associated with tumor invasive factors, uPAR and RhoC. Int J Cancer 125: 1407–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriely, G, Yi, M, Narayan, RS, Niers, JM, Wurdinger, T, Imitola, J et al. (2011). Human glioma growth is controlled by microRNA-10b. Cancer Res 71: 3563–3572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriely, G, Wurdinger, T, Kesari, S, Esau, CC, Burchard, J, Linsley, PS et al. (2008). MicroRNA 21 promotes glioma invasion by targeting matrix metalloproteinase regulators. Mol Cell Biol 28: 5369–5380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krichevsky, AM and Gabriely, G (2009). miR-21: a small multi-faceted RNA. J Cell Mol Med 13: 39–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Würdinger, T, Tannous, BA, Saydam, O, Skog, J, Grau, S, Soutschek, J et al. (2008). miR-296 regulates growth factor receptor overexpression in angiogenic endothelial cells. Cancer Cell 14: 382–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godlewski, J, Krichevsky, AM, Johnson, MD, Chiocca, EA and Bronisz, A (2015). Belonging to a network-microRNAs, extracellular vesicles, and the glioblastoma microenvironment. Neuro Oncol 17: 652–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, S, Patric, IR and Somasundaram, K (2011). A ten-microRNA expression signature predicts survival in glioblastoma. PLoS One 6: e17438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, TM, Huang, W, Park, R, Park, PJ and Johnson, MD (2011). A developmental taxonomy of glioblastoma defined and maintained by MicroRNAs. Cancer Res 71: 3387–3399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- le Sage, C, Nagel, R, Egan, DA, Schrier, M, Mesman, E, Mangiola, A et al. (2007). Regulation of the p27(Kip1) tumor suppressor by miR-221 and miR-222 promotes cancer cell proliferation. EMBO J 26: 3699–3708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina, R, Zaidi, SK, Liu, CG, Stein, JL, van Wijnen, AJ, Croce, CM et al. (2008). MicroRNAs 221 and 222 bypass quiescence and compromise cell survival. Cancer Res 68: 2773–2780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintavalle, C, Garofalo, M, Zanca, C, Romano, G, Iaboni, M, del Basso De Caro, M et al. (2012). miR-221/222 overexpession in human glioblastoma increases invasiveness by targeting the protein phosphate PTPμ. Oncogene 31: 858–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C, Zhang, J, Hao, J, Shi, Z, Wang, Y, Han, L et al. (2012). High level of miR-221/222 confers increased cell invasion and poor prognosis in glioma. J Transl Med 10: 119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, GG, Volinia, S, Croce, CM, Zanca, C, Li, M, Emnett, R et al. (2014). Suppression of microRNA-9 by mutant EGFR signaling upregulates FOXP1 to enhance glioblastoma tumorigenicity. Cancer Res 74: 1429–1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esau, CC (2008). Inhibition of microRNA with antisense oligonucleotides. Methods 44: 55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakimoto, H, Mohapatra, G, Kanai, R, Curry, WT Jr, Yip, S, Nitta, M et al. (2012). Maintenance of primary tumor phenotype and genotype in glioblastoma stem cells. Neuro Oncol 14: 132–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckstein, F (2014). Phosphorothioates, essential components of therapeutic oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acid Ther 24: 374–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heddleston, JM, Hitomi, M, Venere, M, Flavahan, WA, Yang, K, Kim, Y et al. (2011). Glioma stem cell maintenance: the role of the microenvironment. Curr Pharm Des 17: 2386–2401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccirillo, SG, Reynolds, BA, Zanetti, N, Lamorte, G, Binda, E, Broggi, G et al. (2006). Bone morphogenetic proteins inhibit the tumorigenic potential of human brain tumour-initiating cells. Nature 444: 761–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisy, K and Peet, DJ (2008). Turn me on: regulating HIF transcriptional activity. Cell Death Differ 15: 642–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majmundar, AJ, Wong, WJ and Simon, MC (2010). Hypoxia-inducible factors and the response to hypoxic stress. Mol Cell 40: 294–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson, MV, Zheng, X, Pereira, T, Gradin, K, Jin, S, Lundkvist, J et al. (2005). Hypoxia requires notch signaling to maintain the undifferentiated cell state. Dev Cell 9: 617–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X, Linke, S, Dias, JM, Zheng, X, Gradin, K, Wallis, TP et al. (2008). Interaction with factor inhibiting HIF-1 defines an additional mode of cross-coupling between the Notch and hypoxia signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 3368–3373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiang, L, Wu, T, Zhang, HW, Lu, N, Hu, R, Wang, YJ et al. (2012). HIF-1α is critical for hypoxia-mediated maintenance of glioblastoma stem cells by activating Notch signaling pathway. Cell Death Differ 19: 284–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, CJ, Tsai, MM, Hung, PS, Kao, SY, Liu, TY, Wu, KJ et al. (2010). miR-31 ablates expression of the HIF regulatory factor FIH to activate the HIF pathway in head and neck carcinoma. Cancer Res 70: 1635–1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng, H, Kaplan, N, Hamanaka, RB, Katsnelson, J, Blatt, H, Yang, W et al. (2012). microRNA-31/factor-inhibiting hypoxia-inducible factor 1 nexus regulates keratinocyte differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 14030–14034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reardon, DA, Wen, PY, Desjardins, A, Batchelor, TT and Vredenburgh, JJ (2008). Glioblastoma multiforme: an emerging paradigm of anti-VEGF therapy. Expert Opin Biol Ther 8: 541–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, HM, Kim, SH, Jin, X, Park, JB, Kim, SH, Joshi, K et al. (2014). Crosstalk between glioma-initiating cells and endothelial cells drives tumor progression. Cancer Res 74: 4482–4492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd, DH, Kefas, B, Seleverstov, O, Mykhaylyk, O, Dominguez, C, Comeau, L et al. (2012). Alpha-secretase inhibition reduces human glioblastoma stem cell growth in vitro and in vivo by inhibiting Notch. Neuro Oncol 14: 1215–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito, N, Fu, J, Zheng, S, Yao, J, Wang, S, Liu, DD et al. (2014). A high Notch pathway activation predicts response to γ secretase inhibitors in proneural subtype of glioma tumor-initiating cells. Stem Cells 32: 301–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koslowski, M, Luxemburger, U, Türeci, O and Sahin, U (2011). Tumor-associated CpG demethylation augments hypoxia-induced effects by positive autoregulation of HIF-1α. Oncogene 30: 876–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Q, Bartz, S, Mao, M, Li, L and Kaelin, WG Jr (2007). The hypoxia-inducible factor 2alpha N-terminal and C-terminal transactivation domains cooperate to promote renal tumorigenesis in vivo. Mol Cell Biol 27: 2092–2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z, Bao, S, Wu, Q, Wang, H, Eyler, C, Sathornsumetee, S et al. (2009). Hypoxia-inducible factors regulate tumorigenic capacity of glioma stem cells. Cancer Cell 15: 501–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lujambio, A, Calin, GA, Villanueva, A, Ropero, S, Sánchez-Céspedes, M, Blanco, D et al. (2008). A microRNA DNA methylation signature for human cancer metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 13556–13561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valastyan, S and Weinberg, RA (2010). miR-31: a crucial overseer of tumor metastasis and other emerging roles. Cell Cycle 9: 2124–2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurila, EM and Kallioniemi, A (2013). The diverse role of miR-31 in regulating cancer associated phenotypes. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 52: 1103–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y, Song, YX and Wang, ZN (2013). The microRNA-148/152 family: multi-faceted players. Mol Cancer 12: 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, S, Chowdhury, R, Liu, F, Chou, AP, Li, T, Mody, RR et al. (2014). Tumor-suppressive miR148a is silenced by CpG island hypermethylation in IDH1-mutant gliomas. Clin Cancer Res 20: 5808–5822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, W, Zhu, S, Yuan, M, Cui, H, Wang, L, Luo, X et al. (2010). MicroRNA-21 and microRNA-148a contribute to DNA hypomethylation in lupus CD4+ T cells by directly and indirectly targeting DNA methyltransferase 1. J Immunol 184: 6773–6781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdahn, U, Hau, P, Stockhammer, G, Venkataramana, NK, Mahapatra, AK, Suri, A et al.; Trabedersen Glioma Study Group. (2011). Targeted therapy for high-grade glioma with the TGF-β2 inhibitor trabedersen: results of a randomized and controlled phase IIb study. Neuro Oncol 13: 132–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigo, F, Chun, SJ, Norris, DA, Hung, G, Lee, S, Matson, J et al. (2014). Pharmacology of a central nervous system delivered 2'-O-methoxyethyl-modified survival of motor neuron splicing oligonucleotide in mice and nonhuman primates. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 350: 46–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geary, RS, Norris, D, Yu, R and Bennett, CF (2015). Pharmacokinetics, biodistribution and cell uptake of antisense oligonucleotides. Adv Drug Deliv Rev (epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yi, M, Mudunuri, U, Che, A and Stephens, RM (2009). Seeking unique and common biological themes in multiple gene lists or datasets: pathway pattern extraction pipeline for pathway-level comparative analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 10: 200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teplyuk, NM, Uhlmann, EJ, Wong, AH, Karmali, P, Basu, M, Gabriely, G et al. (2015). MicroRNA-10b inhibition reduces E2F1-mediated transcription and miR-15/16 activity in glioblastoma. Oncotarget 6: 3770–3783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, JH, Li, JH, Shao, P, Zhou, H, Chen, YQ and Qu, LH (2011). starBase: a database for exploring microRNA-mRNA interaction maps from Argonaute CLIP-Seq and Degradome-Seq data. Nucleic Acids Res 39(Database issue): D202–D209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong, HK, Veremeyko, T, Patel, N, Lemere, CA, Walsh, DM, Esau, C et al. (2013). De-repression of FOXO3a death axis by microRNA-132 and -212 causes neuronal apoptosis in Alzheimer's disease. Hum Mol Genet 22: 3077–3092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong, HK, Lahdenranta, J, Kamoun, WS, Chan, AW, McClatchey, AI, Plotkin, SR et al. (2010). Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapies as a novel therapeutic approach to treating neurofibromatosis-related tumors. Cancer Res 70: 3483–3493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.