Abstract

Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (DEB) is an incurable skin fragility disorder caused by mutations in the COL7A1 gene, coding for the anchoring fibril protein collagen VII (C7). Life-long mechanosensitivity of skin and mucosal surfaces is associated with large body surface erosions, chronic wounds, and secondary fibrosis that severely impede functionality. Here, we present the first systematic long-term evaluation of the therapeutic potential of a mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC)-based therapy for DEB. Intradermal administration of MSCs in a DEB mouse model resulted in production and deposition of C7 at the dermal-epidermal junction, the physiological site of function. The effect was dose-dependent with MSCs being up to 10-fold more potent than dermal fibroblasts. MSCs promoted regeneration of DEB wounds via normalization of dermal and epidermal healing and improved skin integrity through de novo formation of functional immature anchoring fibrils. Additional benefits were gained by MSCs' anti-inflammatory effects, which led to decreased immune cell infiltration into injured DEB skin. In our setting, the clinical benefit of MSC injections lasted for more than 3 months. We conclude that MSCs are viable options for localized DEB therapy. Importantly, however, the cell number needed to achieve therapeutic efficacy excludes the use of systemic administration.

Introduction

Therapy development for rare diseases is challenging. Small numbers and broad distribution of patients complicate research. Although the prevalence for each of the 5,000–8,000 distinct rare disease is low, it is estimated that 6–8% of the population is affected by a rare disease in the course of their life.1 Thus, over 400 million people worldwide suffer from a rare disease. Despite the difficulties, rare diseases open a valuable chance for basic research. In many cases, the dysfunction of a single biological pathway or a single protein can serve as a model to understand normal physiological functions or the pathology of related common diseases.2

The heritable skin fragility disorder dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (DEB) is a single target rare disease, as mutations in the COL7A1 gene coding for the anchoring fibril protein collagen VII (C7) are the exclusive cause of this EB subtype.3,4 C7 is secreted by dermal fibroblasts and epidermal keratinocytes. As a specialized protein component of the dermal-epidermal junction zone (DEJZ), it ensures skin integrity and stability.5,6 High-affinity interactions with major basement membrane molecules, namely laminin-332 and collagen IV, and with dermal collagen I-containing fibers are responsible for the unique adhesive properties of C7.7

Currently, more than 800 distinct COL7A1 mutations are known,8,9 resulting in a heterogeneous spectrum of clinical severity of trauma-induced skin blistering and scarring.10 The genotype–phenotype correlations are not well understood, but in general partially functional C7 is associated with a milder phenotype than its complete absence. In severe recessive DEB (RDEB), repeated cycles of skin blistering and healing with excessive scarring result in soft tissue fibrosis and fusion of the digits at the extremities, so called mitten deformities. At the sites of severely abnormal fibrotic dermis and unsuccessful wound regeneration, aggressive squamous cell carcinoma often arises; this is the leading cause of death in RDEB.11

With C7 as an exclusive target, different gene-, protein-, cell-based, or pharmacologic therapy approaches have been investigated,12,13,14 some of which have resulted in pilot clinical trials.15,16,17 However, despite promising preclinical data, the therapies have only shown limited clinical benefits, and a curative and safe therapy is still not available.

Bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) are a potentially alternative cell-based treatment for DEB.18,19 Currently, more than 400 clinical trials using MSCs are listed (http://clinicaltrials.gov). Allogeneic MSCs are commonly well tolerated due to their immune-modulating effects20,21 and have been shown to promote wound healing and tissue regeneration.22,23 In RDEB, MSCs have the potential to work on two separate mechanisms to restore skin integrity. On one hand, MSCs could promote wound healing by homing to wounded tissue and stimulating regeneration through paracrine immune-modulating mechanisms.24 On the other hand, they could synthesize and secrete C7, deposit it at the DEJZ and thus restore skin integrity.

Here, we evaluated the feasibility and efficacy of an MSC-based therapy approach in a preclinical setting using human bone marrow–derived MSCs in RDEB mice25 and showed that MSCs are a viable source of C7 in vitro, independent of donor age and passage number. In vivo, intradermally injected MSCs secreted functional C7, which was incorporated at the DEJZ in a dose-dependent manner. Injections of 2 million MSCs/cm2 facilitated wound regeneration, and inflammation and granulation tissue maturation were normalized. MSC-injected wounds exhibited restoration of immature anchoring fibrils and better dermal-epidermal integrity than phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-injected wounds. Already at a concentration of one tenth of that used for fibroblast-based RDEB therapy (i.e., 500,000 MSCs versus 5 million fibroblasts26), MSCs efficiently promoted C7 deposition. No adverse events were detected. In conclusion, intradermally injected MSCs show excellent promise as a safe treatment option for limited skin areas in RDEB; however, the cell number required for an efficacious treatment is too high to be achieved by systemic intravenous delivery.

Results

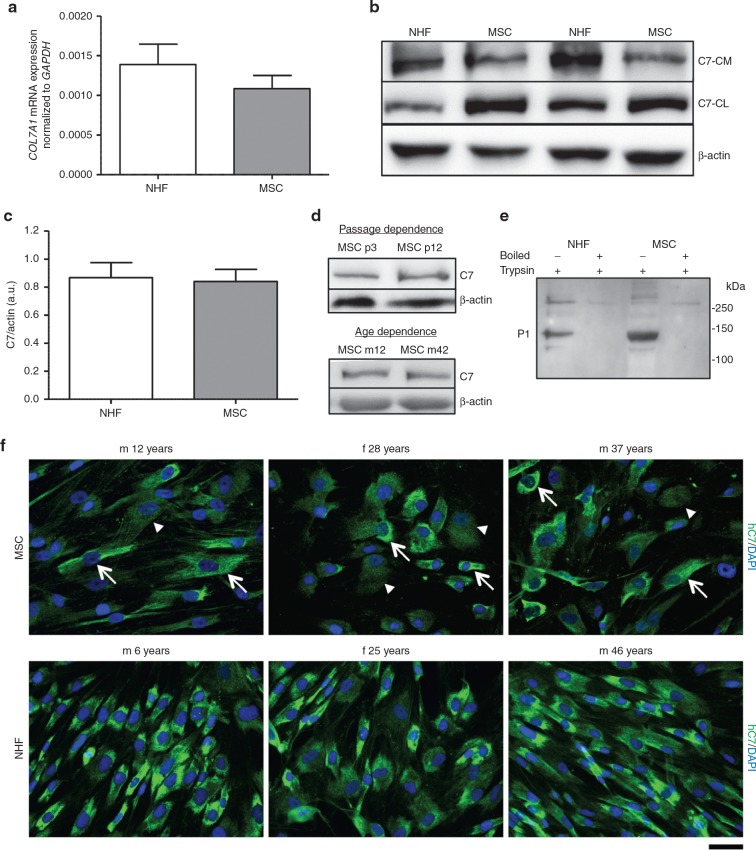

MSCs stably express and secrete C7

MSCs possess high regenerative potential, can be produced on a large scale under GMP conditions and share many similarities with dermal fibroblasts.27 This led us to evaluate whether they are suitable for cell-based therapy for RDEB. We first compared the expression and secretion of C7 in human MSCs with normal human dermal fibroblasts (NHFs) in vitro. On mRNA level, both cell types showed comparable expression of human C7 (Figure 1a). On protein level, C7 present in three different culture compartments was analyzed: in the cell layer, in the extracellular matrix, and in the culture medium. Analysis of MSCs of ≥ 9 different donors for each group revealed a comparable C7 expression between NHFs and MSCs (Figure 1b,c) in vitro, although slightly higher amounts of secreted C7 were found in NHF conditioned medium (Figure 1b). To exclude donor-dependent effects on C7 expression, we screened MSCs from multiple different donors (≥ 20) of varying age (11–46 years) and gender, and of different passage number. Donor-related differences in C7 expression (Supplementary Figure S1) and secretion were not detected. MSCs and NHFs from different donors showed similar low variation in C7 expression; C7 over β actin signal 0.84 ± 0.09 for MSCs and 0.87 ± 0.11 for fibroblasts, respectively (Figure 1c). Even in high cell passages, C7 expression remained stable (Figure 1d). The ability of the MSC-secreted C7 to form a stable collagen triple helix was assessed by limited trypsin digestion (Figure 1e). MSC-expressed C7 was tested vis-à-vis NHF-expressed C7. Both were resistant to trypsin proteolysis, indicating that MSCs indeed secreted well-folded triple-helical C7. To validate the quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and western blotting findings, we performed immunofluorescence stainings of NHFs and MSCs seeded on glass cover slips. Both cell types exhibited a strong C7 staining in the cytoplasm (Figure 1f). Of note, while practically all NHFs showed a strong C7 signal, the picture in MSCs was more heterogeneous, with mixed low and high C7 expressers (white arrows and arrowheads in Figure 1f). In conclusion, bone marrow–derived human MSCs represent a viable and stable source for human C7.

Figure 1.

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) stably express and secrete C7. (a) Quantitative real time polymerase chain recation of COL7A1 expression in normal human fibroblasts (NHFs) and MSCs with GAPDH as reference gene. n ≥ 9 different donors per group in three independent experiments. Values are mean ± SEM. (b) Western blots of representative experiments. NHFs and MSCs were seeded in six-well plates and grown to 80% confluence before adding serum-free culture medium + 50 µg/ml ascorbic acid for 48 hours. Conditioned medium was precipitated with ammonium sulfate and analyzed by western blotting, cells and matrix were extracted and processed for western blot analysis, too. Western blots were run under reducing conditions. Blots were probed with antibody against C7 and β-actin as loading control. (c) Densitometric quantification of three independent western blots of cell and matrix lysates. n ≥ 9 different donors per group in three independent experiments. Values represent mean ± SEM of C7 expression in NHFs and MSCs normalized to β-actin expression. (d) C7 expression in MSCs in correlation to passage number and donor age. A representative western blot of cell and matrix lysates of the same donor in a low (passage 3) and a high (passage 12) passage number and between a young (12 years) and an older (42 years) donor are shown. Western blots were run under reducing conditions. Similar C7 expression was detectable in all presented settings. (e) Limited trypsin digestion assay of secreted C7. Conditioned medium was pelleted as described above (b); the pellets were resuspended in TBS and digested with 0.05% trypsin at 30 °C for 10 minutes. Positive controls were boiled prior to trypsin digestion. Western blotting was performed as described above and probed with antibody recognizing the P1 fragment of C7. MSC-derived C7 was resistant to trypsin proteolysis suggesting stable triple helical configuration. (f) Representative images of NHFs and MSCs from different donors seeded on collagen I coated glass slides for 48 hours in the presence of 50 µg/ml ascorbic acid and stained for human C7 (green). In MSCs, a mix of C7 high (white arrows) and low (white arrowheads) expressing cells was detected. Nuclei (blue), bar = 50 µm.

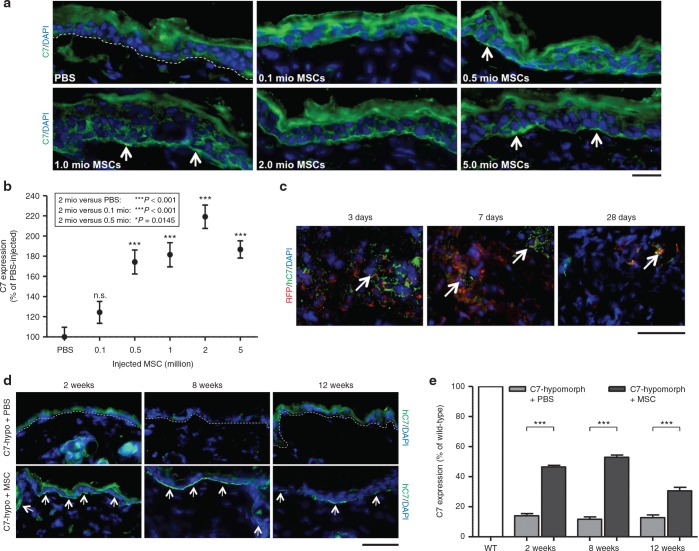

MSCs produce and deposit C7 at the DEJZ after intradermal delivery

After determining that MSCs produced physiologically relevant amounts of C7, we proceeded to test the therapeutic applicability of MSCs in vivo by injecting them intradermally into C7-hypomorphic mice, an RDEB model.28 First, we concomitantly assessed their ability to increase C7 at the DEJZ and the appropriate cell number required to do so compared to PBS-injected animals. The cell number range was based on previous preclinical investigations of MSC-stimulated wound healing and a fibroblast-based therapy approach for RDEB.26,29 0.1–5 × 106 MSCs were injected intradermally into a defined 1 cm2 area on the back skin of C7-hypomorphic mice twice, with an interval of 1 week. One week after the last injection, C7 expression in MSC-injected skin was analyzed by immunofluorescence staining and compared to PBS-injected C7-hypomorphic skin. It was evident that injections of MSCs increased C7 deposition at the DEJZ and that this effect was dose-dependent (Figure 2a). For semiquantitative assessment, we set the residual C7 expression in PBS-injected C7-hypomorphic skin to 100%. Quantification of the C7 fluorescence signal revealed that injection of 0.5–5 × 106 MSCs/cm2 clearly resulted in a significant and dose-dependent but not linear increase of C7 deposition (Figure 2b). While injection of 0.1 × 106 MSCs/cm2 showed only limited effects, injections of 0.5 or 1 × 106 MSCs/cm2 significantly increased the C7 deposition to 174 ± 12% and 182 ± 12% (for both ***P < 0.001), respectively. After 1 week, the most intense C7 fluorescence signal was detectable after injection of 2 × 106 MSCs/cm2 into the C7-hypomorphic skin, 219 ± 12 % (***P < 0.001), as compared to PBS-injected C7-hypomorphic mouse skin (Figure 2b). Injection of higher numbers of MSCs/cm2 did not further improve C7 deposition; injection of 5 × 106 MSCs generated a C7-signal intensity of 187 ± 9 % (***P < 0.001), as compared to PBS-injected controls. Based on these data, 2 × 106 MSCs/injection were used in all subsequent treatments. No macroscopic signs of discomfort or signs of inflammation areas were observed during or after the injections. On the microscopic level, a mild transient (< 7 days) inflammation was detectable in both MSC- (Supplementary Figure S2) and PBS-injected groups (data not shown).

Figure 2.

C7 is deposited at the dermal-epidermal junction zone after injection of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs). (a) Different cell concentrations and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) alone were injected intradermally in the back skin of C7-hypomorphic mice twice with a 7-day interval. One week after, the last injection skin was analyzed for presence of C7 with an antibody detecting both human and murine C7 (green). MSC-injected mice showed dose-dependent C7 deposition at the dermal-epidermal junction zone with a maximum at 2 × 106 injected MSCs. Arrows depict C7-positive areas. (b) Photographs of skin sections from (a) were taken with identical image settings and C7 deposition was quantified with Image J. Quantification revealed the highest C7 deposition after injection of 2 × 106 MSCs. n = 3 repeats of each cell concentration in three independent experiments. Values represent mean ± SEM of C7 expression normalized to PBS-injected hypomorphic skin. Asterisk above the data points indicate P values of cell concentrations compared with PBS. n.s., not significant, ***P = <0.001. P values in the box represent differences between the most efficient cell number (2 × 106 MSCs) and other treatment regimens as indicated. (c) Single dose of 2 × 106 MSCs expressing the red fluorophore mCherry (RFP) were injected intradermally in the back skin of C7-hypomorphic mice. Three to 28 days after injection, skin samples were analyzed for RFP+ cells (red) and human C7 using human-specific antibody (green). RFP+ cells, which simultaneously express human C7 (green), decrease over time but a few are still visible after 28 days. (d) C7 stability was assessed by immunofluorescence analysis 2–12 weeks after a repeated intradermal injection of 2 × 106 MSCs in the back skin of C7-hypomorphic mice. Human C7 deposition detected as in (c) (green) is clearly visible 2 and 8 weeks after MSC injections and in a reduced amount after 12 weeks. In contrast, in PBS-injected mice, a weak barely detectable C7 signal was seen at all time points. Arrows indicate C7-positive areas at the dermal-epidermal junction zone. Skin sections as in (d) stained with an antibody detecting both sources of C7. Pictures were taken with identical image settings and C7 deposition was quantified with Image J. Quantification revealed significant increase in C7 deposition 2, 8, and 12 weeks after injections of MSCs, as compared to PBS-injected mice. n ≥ 3 per group. Values represent mean ± SEM of C7 expression normalized to uninjected wild-type skin. ***P < 0.001. Bar = 50 µm.

MSCs possess the ability to induce protein expression in the host cells through paracrine signaling.29,30 Since the literature contains controversial statements about whether C7 expression can be induced in a paracrine manner after fibroblast injections,15,26 it was of interest to determine if C7 produced by the injected MSCs directly contributed to the increase of C7 in the present context. Since the C7-hypomorphic mouse retains about 10% of physiological C7 expression levels, we used species-specific antibodies to assess the cellular source of newly produced C7. New antibodies reacting with human, but not mouse C7, were developed as described in Supplementary Materials and Methods and Supplementary Figure S3. Staining of PBS- or MSC-injected C7-hypomorpic mouse skin clearly showed presence of human C7 after MSC administration but not after injection with PBS alone (Figure 2c,d). Although we cannot exclude paracrine upregulation of endogenous C7 expression through MSCs injections with certainty, we did not detect increased deposition of murine C7 after treatment with PBS alone, indicating that any non-MSC-related paracrine effects would be quantitatively minor.

MSCs remain in the skin up to 28 days after intradermal delivery

In order to assess the stability of the therapeutic MSCs in the dermis, 2 × 106/cm2 of MSCs stably expressing the red fluorophore mCherry (RFP) were injected into the back skin of C7-hypomorphic mice. Fluorescence microscopy revealed red cells expressing human C7 in MSC-injected areas 3–28 days after injection (Figure 2c), whereas no red signal was detected at other skin areas of the same mouse (not shown). The number of RFP+ cells decreased over time, suggesting that the cells survived, but did not proliferate for 4 weeks after the injection. Staining with the human C7-specific antibody further revealed that the injected MSCs produced human C7 for approximately 28 days after injection (Figure 2c). Terminal desoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assays showed that the decrease of MSCs was due to apoptosis; control skin areas showed no sign of dermal cell apoptosis, whereas MSC-injected areas contained apoptotic cells within the dermis. The number of apoptotic cells gradually increased over time suggesting that most of the injected cells underwent apoptosis 4 weeks after injection (Supplementary Figure S4).

MSC-derived C7 is stable at the DEJZ for at least 12 weeks

To evaluate the stability of the newly produced C7 integrated at the DEJZ, skin specimens of C7-hypomorphic mice were analyzed 2, 8, and 12 weeks after MSC or PBS injections. Immunofluorescence staining with human C7-specific antibodies revealed a strong signal in MSC-injected skin after 2 and 8 weeks and a reduced but still visible staining after 12 weeks (Figure 2d), while the signal was completely absent in PBS-injected C7-hypomorphic mice (Figure 2d). To gain information about the efficacy of the MSC treatment we compared the deposited C7 amount with wild-type and PBS-injected C7-hypomorphic mice, respectively (Figure 2e). For semiquantitative purposes, the wild-type signal was set to 100%. In PBS-injected C7-hypomorphic skin, the signal corresponded to 14.1 ± 1.4%, 11.7 ± 1.6%, and 12.8 ± 1.8% after 2, 8, and 12 weeks, respectively. MSC injections significantly increased C7 deposition at all analyzed time points compared to PBS injections (for all ***P < 0.001). In MSC-injected skin, 2 weeks after the last injection, the C7 signal was 46.4 ± 1.1% and after 8 weeks 53.0 ± 1.4% of wild-type level, indicating that MSCs promoted a three- to fourfold increase of C7 at the C7-hypomorphic DEJZ. After 12 weeks, the C7 signal had declined to 30.6 ± 2.3%, but was still about twofold higher than in PBS-injected controls (Figure 2e). Importantly, we did not detect signs of specific immune reactions to the de novo deposited C7 (Supplementary Figure S5), indicating that they were not a prime cause of C7 decrease at later time points but that this was rather due to natural turnover of the protein. These findings indicate that MSC-derived C7 is stable at the DEJZ for at least up to 3 months.

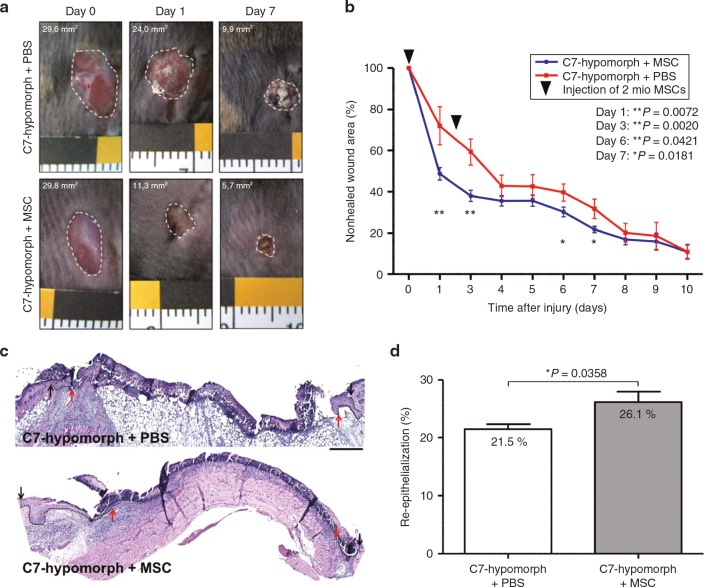

MSC injections facilitate wound healing in RDEB mice

RDEB patients struggle with chronic wounds, which harbor the risk of squamous cell carcinoma development, and we have previously shown that acute wounds in C7-hypomoric mice replicate many features of perturbed wound healing in RDEB.28 Since MSCs have potential to stimulate wound regeneration31,32 and the ability to produce C7, they could confer dual benefits for patients. Accordingly, we investigated the effects of MSC injections in wounded C7-hypomorphic and control mice. 2 × 106 MSCs were injected into the edges of full-thickness skin wounds 8 and 56 hours after wounding. While injections of MSCs into wild-type wounds did not affect gross wound healing compared to PBS-injected wounds (Supplementary Figure S6), injections of MSCs into wounds of C7-hypomorphic mice accelerated wound closure (Figure 3a,b). At day 1, the wound area was reduced to 48.7 ± 3.0% in MSC-injected wounds, whereas PBS-injected wounds still exhibited 72.1 ± 9.3% (**P = 0.0072) of the original wound area (Figure 3b). At days 3, 6, and 7, the MSC-injected wounds remained significantly smaller than PBS-injected wounds (day 3, 38.1 ± 2.7% versus 59.3 ± 6.4% (**P = 0.0020), day 6, 30.3 ± 2.4% versus 39.7 ± 4.1% (*P = 0.0421), and day 7, 21.8 ± 1.6% versus 31.8 ± 4.7% (*P = 0.0181)), but at later time points, no significant difference in wound closure was noted between the MSC- and PBS-injected groups. Re-epithelialization was accelerated in MSC-injected wounds, as assessed by epithelial tongue progression (Figure 3c). After day 3, the epithelial coverage was 26.1 ± 1.8% in MSC-injected wounds compared to 21.5 ± 0.8% (*P = 0.0358) in PBS-injected wounds (Figure 3d).

Figure 3.

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) normalize gross wound closure and re-epithelialization. (a) Closure of 6-mm full thickness punch biopsies on the back of C7-hypomorphic mice over time. Mice were injected either with PBS or MSCs. (b) Quantification of the wound area revealed an accelerated wound closure in mice injected with MSCs compared to phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-injected wounds. n ≥ 12 wounds per group; values represent mean ± SEM. P values are stated in the figure. (c) H&E staining of 3-day-old wounds from C7-hypomorphic mice injected either with PBS or MSCs. Arrows indicating wound width (initial wound boarder; black arrows, epithelial front; red arrows, re-epithelialized area is highlighted with dotted black line). Starting with the same wound size, MSC-injected animals show an accelerated re-epithelialization of wounded tissue after 3 days. Bar = 250 µm. (d) Quantification of re-epithelialized area 3 days after wounding in percent of the maximal wound size. n = 5 wounds per group. Values represent mean ± SEM,*P = 0.0358.

We have previously reported that wound healing in the C7-hypomorphic mouse is accompanied by slower dermal healing manifested in delayed myofibroblast maturation and prolonged presence of inflammatory cells.28 Hematoxylin and eosin stainings clearly revealed disparate appearance of the granulation tissue in MSC-injected versus PBS-injected wounds. In general, the formed granulation tissue in wounds receiving MCSs appeared denser and thicker than in wounds receiving PBS alone (Figure 3c). MSC-treatment normalized dermal wound healing by shifting the granulation tissue formation and the inflammatory state of the wound toward the wild-type situation. Injection of MSCs reduced the number of Cd11b+ cells at day 7 as compared to PBS-injected wounds (Figure 4a,c). Furthermore, the wound center in MSC-injected wounds clearly contained αSMA-positive myofibroblasts, while in PBS-injected wounds myofibroblasts were sparse and preferentially present at the wound edges (Figure 4b). The total smooth muscle actin (αSMA) positive area in MSC-injected wounds at day 7 was larger than in PBS-injected wounds (Figure 4c). These findings show that MSCs efficiently stimulate both dermal and epidermal healing of RDEB wounds.

Figure 4.

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) ameliorate inflammation and granulation tissue maturation in C7-hypomorphic mouse wounds. (a) CD11b staining (red) in 7-day-old wounds revealed prolonged inflammation in C7-hypomorphic mice compared to wild-type animals as previously described in ref. 28. Treatment with MSCs alleviated inflammation in C7-hypomorphic wounds. Bar 200 µm. Cell nuclei are stained with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue). (b) α-SMA staining (red) indicated presence of myofibroblasts in the wound center in wild-type mice compared to peripheral distribution in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-injected C7-hypomorphic mice. In MSC-injected wounds, myfibroblasts were more abundant and centrally localized indicating a more matured granulation tissue. Bar = 100 µm. (c) Quantification of total amount of CD11b+ cells in the wound area (left, *P = 0.0364) and α-SMA-positive area (right, *P = 0.044). n ≥ 3 wounds per group; values represent mean ± SEM.

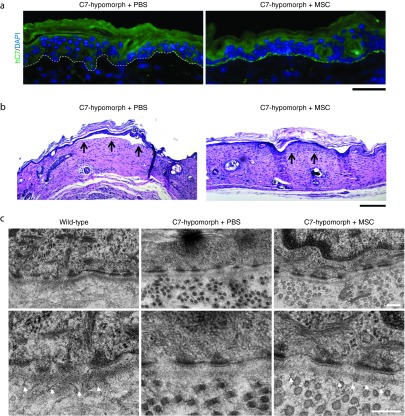

Injections of MSCs increase stability of healed wounds

Anchoring fibrils are significantly diminished in C7-hypomorphic mice causing sensitivity to frictional damage of the skin.25,28 From a therapeutic standpoint, it was valuable to determine if MSC injection also promoted stabilization of healed wounds.26 First, MSC injections resulted in deposition of human C7 at the DEJZ of healed wounds (Figure 5a). Second, MSC injections promoted resistance to shearing forces. Functionally, healed MSC- and PBS-injected wounds were mechanically challenged by a tape strip assay using three cycles of adhesion and snap removal of tape strips. Subsequent morphological analysis revealed less epidermal detachment in MSC-injected wounds than in PBS-injected wounds (Figure 5b). Finally, electron microscopy was employed to assess formation of anchoring fibrils in 12-week healed wounds. Indeed, MSC-injected wounds exhibited increased immature anchoring fibrils in selected areas, but wounds that had only received PBS were devoid of the fibrils (Figure 5c and Supplementary Figure S7a,b). In line with previous studies,33,34 quantification revealed 3.8 ± 0.3 anchoring fibrils/µm lamina densa with an average maximal thickness of 32.5 ± 1.6 nm in wild-type skin (Supplementary Figure S7a,b). After 12 weeks, healed MSC-injected hypomorphic wounds contained 2.1 ± 0.5 immature anchoring fibrils/µm lamina densa with a thickness of 19.6 ± 1.3 nm compared to wild-type fibrils. However, even though not of perfect ultrastructure, the fibrils were clearly functional and stabilized the skin (Figure 5b). Collectively, the data show that MSCs not only promote dermal and epidermal healing but also significantly improve the functional integrity of healed RDEB skin.

Figure 5.

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) increase skin stability of healed wounds. (a) Human C7 deposition at re-epithelialized 7-day-old wounds. In phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-injected wounds, there is no sign of C7 deposition, whereas healed wounds treated with MSCs show a clear deposition of human C7 at the dermal-epidermal junction zone of healed wounds. Bar = 50 µm. (b) Tape strip assay of 4-week-old healed skin wounds revealed increased skin stability in MSC-injected wounds compared to PBS-injected skin. Healed full thickness skin wounds were mechanically stressed through repeated tape stripping and skin sections were analyzed for epidermal-dermal detachment (black arrows). Representative pictures of four wounds per group are shown. Bar = 200 µm. (c) Transmission electron microscopy images of skin from wild-type mouse and 12-week-old healed wounds from C7-hypomorphic mice treated either with PBS or MSCs. Analysis revealed absence or formation of scarce amounts of mainly unstructured anchoring fibrils in PBS-injected mice, whereas in MSC-injected mice, immature anchoring fibrils were visible in some areas 12 weeks after wounding (white arrowheads). Pictures were taken at 15,000× magnification. Bar = 200 nm.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that intradermal injections of bone marrow–derived MSCs can serve as an attractive option to improve RDEB. Despite promising progress on various therapy approaches for DEB,12,14 no evidence-based curative therapy is currently available. MSCs not only provide a natural C7 source after intradermal administration but also promote wound healing and increase skin stability in RDEB. MSCs perform these functions at a considerably lower cell number than dermal fibroblasts.26,35 This observation, together with the availability of GMP-quality MSCs and their well-documented long-term use in patients, makes these cells appear suitable for cell-based RDEB therapy. In addition, their immune-modulating capacity eliminates the need for donor match.36

MSCs share many features with fibroblasts,27 thus we assessed them vis-à-vis dermal NHFs, which have already been proven to have therapeutic potential for DEB.26,35,37 In vitro, MSCs expressed and secreted C7 in a stable triple helical configuration at levels comparable to NHFs. However, in vivo in our preclinical setting, MSCs exhibited therapeutic effects similar to dermal fibroblasts, but up to 10 times fewer cells were required to do so.26 Use of a lower cell number would be beneficial as it would allow smaller volume per injection and less pain associated with intradermal injections. Fewer cells needed for treatment may also grant the possibility to treat larger body surface areas. Another major advantage is the known immune-modulating effect of MSCs36 that is also likely to suppress inflammation in RDEB skin.25,28

Although donor-related differences for MSCs can be common,38 in our system C7 expression in MSCs was stable over many passages with limited variation between different donors. However, within MSCs from the same donor, we did observe subpopulations consisting of high and low C7 expressing cells. This opens up an option of therapy optimization. If the subpopulations also exhibit distinct expression of cell surface markers, cell sorting could be used to enrich for MSCs with high C7 expression. Since injected MSCs do not divide and are lost over time, repeated cell administration will be needed. Although the intervals can be as long as a few months, a sorting step prior to injections could improve C7 deposition in vivo and thus prolong the time span between injections even more.

After the injections, the number of MSCs gradually decreased, and nearly all cells had undergone apoptosis by 28 days in this xenogeneic setting, which is similar to what we previously observed after injection of allogeneic fibroblasts in the same model.26 A more sensitive detection method might provide evidence for a longer existence of some MSCs in the skin. In comparison, corrected syngeneic iPS cells which were differentiated to fibroblasts were detectable up to 16 weeks after injection.39 Although MSCs have the ability to differentiate to multiple mesenchymal cell types in vitro, it is generally accepted that long-term engraftment does not occur.40 In our system, we saw no evidence that the gradual loss of MSCs was caused by immune reaction to the foreign cells. In this context, it is essential to stress that mice exposed to human MSCs maintain the ability to mount immune response to foreign proteins, but the mice do not mount one to the MSCs after single or repeated exposure.41

No signs of adverse events were noticed after repeated MSC administration. Macroscopically, redness, indications of pain, or itching were not observed. Microscopically, a mild transient inflammation was detectable but it subsided within 1 week in both MSC- and PBS-injected groups. We repeated MSC injections into intact skin after 1 week in order to reduce variation between individual mice and treated areas. Furthermore, importantly, an interval of 7 days was sufficient to give the host time to mount a potential immune response to the injected cells or their secreted proteins, including C7. No linear murine IgG or C3 deposition was detected at the DEJZ and skin-resident T cells were not increased (Supplementary Figure S5), indicating that the host did not raise a specific immune response to the de novo deposited human C7.

An optimal RDEB therapy should achieve restoration of anchoring fibrils that are necessary for skin stability. In this study, de novo immature anchoring fibrils were observed in MSC-injected skin, in contrast to our previous preclinical fibroblast-therapy investigation that failed to demonstrate formation of the fibrils.26 Collectively, the data indicate that MSCs promote C7 processing and/or anchoring fibril assembly more efficiently than dermal fibroblasts.

RDEB wounds display multiple deviations from wild-type wounds,28 but MSC-treatment shifted the wound healing process toward a wild-type phenotype. These effects are likely a combination of C7-dependent and C7-independent mechanisms. Most RDEB wounds have the ability to close. However, exposure to friction leads to frequent rewounding, eventually causing chronic wounds, fibrosis, and malignant transformation. MSCs promoted wound closure but their main advantage was that they deposited normal C7, which significantly increased frictional protection. In a previous study, we showed that 30% of wild-type level C7 was sufficient for substantial protection of the skin from frictional damage.26 Twelve weeks after MSC injections, similar levels of C7 were present at the DEJZ and immature anchoring fibrils were detected in wounds of similar age, yet again indicating that 30% C7 is sufficient for adequate skin stabilization. The effects on re-epithelialization and dermal healing also encompass paracrine stimulation from MSCs, since MSCs have been shown to promote healing in other settings.23,29 Interestingly, MSCs alleviated inflammation and, although debated, inflammation is linked to dermal scarring.42 Moreover, reduced inflammation is also likely to reduce pain associated with wounds in RDEB.

For all the above reasons, local intradermal injections of MSC display excellent therapeutic potential for RDEB. We are aware that multiple and repeated localized injections represent a major limitation of this approach, since in its natural course RDEB affects large body surfaces and sites not readily amenable for injections, e.g., the esophagus, and since chronically inflamed and scarred skin may be too painful to inject. Therefore, systemic delivery of MSC would be preferable.

However, in case of systemic application of MSCs, the low engraftment rates in wounded tissue are a major concern.22,23 Here, we demonstrate that 0.5–2 million MSCs/cm2 are required for substantially increased C7 at the DEJZ and for a significant therapeutic benefit. It is well established that the large majority of systemically injected MSCs become trapped in the lung and that very few cells reach peripheral organs,24 although tissue damage may promote accumulation. One study showed that 3 days after intravenous MSC administration, only 0.07% of the cells were present in a 0.8 cm2-sized dermal mouse wound.23 Based on this study,23 an infusion of approximately 0.7 × 109 cells would be needed to reach a concentration of 0.5 million cells in a 1 cm2 skin wound. Patients with involvement of > 10% of body surface can be viewed as suffering from a generalized form of RDEB.43 Assuming a body surface area of approximately 1.1 m2 in the average adult patient with severe generalized RDEB and engraftment of 0.07%,23 an infusion of approximately 0.8 × 1012 MSCs would be needed to reach a therapeutic concentration of 0.5 million MSCs/cm2 skin surface. Thus, intravenous administration of MSCs as a source of C7 is currently unfeasible. This is supported by a case report describing minimal clinical improvement of RDEB after MSC infusion.44 Moreover, in preliminary studies, we infused C7 hypomorphic mice with 1 million MSCs, which was the maximal number that could be infused without danger of adverse events such as emboli. We did not detect an increase of C7 in healed wounds 14 days after infusion (data not shown). This is in line with that Tolar et al.45 who showed that the RDEB phenotype of C7 knockout mice could not be ameliorated with MSC-infusions. Nevertheless, MSCs may contribute to patient well-being by nonspecific paracrine signaling that has been shown to occur even at sites distant from the injured tissue.24,41 Further, significant efforts are undertaken to improve engraftment efficiency of MSCs,46 giving hope for systemic treatment options in the future.

In conclusion, MSCs are a valuable option as a causative therapy for RDEB when administered intradermally in sufficient concentrations. Despite limitations of intradermal injection therapies, MSCs are promising, since they are widely available, easily expandable under GMP-conditions and already used for human therapies, a fact that will minimize safety concerns and ease rapid clinical implementation.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement. All animal experiments were approved by the regional ethics review board (Regierungspräsidium Freiburg), ethical approval number G13/68. The mice were housed in a clean facility with water, food, and supportive nutrition ad libitum. MSCs were derived from excessive material of standard bone marrow aspirates. Excess material was used after given written informed consent (ethical approval number 76/2009BO2). Follow-up of C7-hypomorphic mice for more than 12 weeks was not possible due to the burden of DEB in the C7-hypomorphic mice.

Antibodies. The following antibodies were used: rat anti-CD11b (BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany), Cy3-conjugated mouse anti–α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) (Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany), rabbit anti–COL7A1 (Millipore, Schwalbach, Germany), mouse anti–β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich), mouse anti-COL7A1 (Sigma-Aldrich), rabbit anti-COL7A1 (Eurogentec, Cologne, Germany), rabbit anti-C3 (Dako, Hamburg, Germany), biotinylated hamster anti-CD3e (BD Pharmingen, Heidelberg, Germany), rabbit anti-NC2-10 for C7 P1 fragment.47 Secondary antibodies were Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti rabbit (Invitrogen, Darmstadt, Germany), Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti rat (Invitrogen), Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti mouse (Invitrogen), streptavidin Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated (Invitrogen), HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse and anti-rabbit (Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories, Newmarket, UK)

Isolation and expansion of human MSCs. Human MSCs were cultured in the Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) facility at the Department of General Paediatrics, Haematology/Oncology in Tübingen using animal serum-free medium as described previously.48,49 In brief, 10–15 ml bone marrow (BM) aspirates of healthy donors were resuspended in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)) medium (1 g/l glucose) supplemented with 80 IU/ml heparin sulfate, 1 mmol/l glutamine and 108/ml irradiated human platelets. After 2–3 days of incubation at 37°C and 10% CO2, nonadherent cells were removed. MSCs were expanded over a period of 3–4 weeks and harvested using TrypLE Select (Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany). For transfer to the Department of Dermatology Medical Center University of Freiburg, MSCs were frozen in 1 ml 0.9% NaCl mixed with 1 ml human serum albumin containing 20% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

Microbial analyses for aerobe and anaerobe bacterial, fungal, and mycoplasma infections at the beginning of the MSC cultures, after about 10 days and during harvesting, demonstrated that the cells were free of bacterial and fungal contaminations. In addition, cell number, vitality (as determined by propidium iodide staining), and purity of MSC were defined by flow cytometry on the basis of CD73, CD105 (positive markers), CD45 (negative marker), CD14 (to exclude monocytes), and CD3 (to exclude T cells in MSC cultures). All these checks ensured that cells of very high quality were used.

Plasmid construction and retrovirus production. The sequence mCherry was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using Pfu-polymerase kit (Promega, Mannheim, Germany) and the following primers (MWG Operon, Ebersberg, Germany) containing XhoI and EcoRI restriction sites, respectively: Forward 5′ GGGAA CTCGAG ATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAG 3′, Reverse AAAGG GAATTC TCACTTGTACAGCTCGTC.

The PCR product was cloned into the pMSCV puro vector (Clontech, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France) and correct insertion was verified by sequencing (MWG Operon). Midiprep plasmid purification was performed as recommended by the manufacturer (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

For retrovirus production, HEK293T cells were cultivated in DMEM (+ 1 mmol/l glutamine, 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, 10%FCS) at a density of 70,000/cm2 in a 25 cm2 flask and 5 µg of plasmid DNA mix (consisting of 1.5 µg pMD (gag/pol) + 0.5 µg psRAG-1 (env) + 3 µg pMSCV-mCherry) was transfected into HEK293T cells using jetPei transfection reagent (Peqlab, Erlangen, Germany) and 50 µmol/l chloroquine (Sigma-Aldrich). Cell culture supernatants were collected every 24 hours over a period of 4 days, passed through a filter with 0.45 µm pore-size, supplemented with 6 µg/ml polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich) and used for infection of FLYRD18 cells (2,000/cm2 in a six-well plate).50,51 For better infection efficiency, FLYRD18 were centrifuged at 600 g for 2 hours at 37 °C. Positive selection of transfected cells was achieved by the use of 2.5 µg/ml puromycin + 4 µg/ml blasticidin + 10 µg/ml phleomycin (InvivoGen, Toulouse, France). After 2–3 days, infection rate was determined by flow cytometry.

Stable expression of fluorescence reporter genes in human MSCs. FLYRD18 (70,000/cm2) were seeded in 3 ml Quantum 333 medium in 25 cm2 flasks and sterile filtered cell culture supernatants were used for infection of MSCs, which were plated at 5,700/cm2 in six-well plates the day before.52 Successful retroviral infection of MSCs was achieved with 6 µg/ml polybrene and performing two infection cycles.

Surface marker expression, as well as adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation of MSCs were not influenced by retroviral transfection. In addition, expression of fluorescence signal in MSCs remained stable over a period of at least 10 weeks in cell culture (data not shown).

Western blotting and limited trypsin digestion assay. Confluent cells were washed three times with PBS and 12 ml serum free culture medium with 50 µg/ml ascorbic acid was added into T-75 flasks for 48 hours. The medium was harvested and centrifuged at room temperature for 5 minutes at 1,000 rpm to clear cell debris. The supernatant was harvested and 10 mmol/l ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and protease inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich) were added. The medium was chilled to +4 °C and ammonium sulfate (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) was added to a final concentration of 30%. The medium was precipitated at +4 °C for 2 hours under slow rotation and precipitated proteins were collected by centrifugation at 4,000 rpm at +4 °C for 30 minutes. The entire protein pellet was dissolved in 1× blue sample buffer (BSB) and used for western blot analysis. Cells were extracted with NP-40 lysis buffer kept on ice for 30 minutes and centrifuged at 16,000 rcf at +4 °C to remove cell debris. Lysates and conditioned medium were boiled in sample buffer containing 8 M urea, separated on 7% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gels under reducing conditions, and elctrotransferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Roth). Membranes were blocked in 5% milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS)-Tween (0.1%) and incubated with primary antibody, washed in TBS and probed with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies. Blots were developed by electrochemiluminescence (ECL) (Thermo Scientific, Braunschweig, Germany) and detected using a chemiluminiscence detection system (Peqlab, Erlangen, Germany). Limited trypsin digestion was performed to assess C7 stability.53 Serum-free conditioned medium was precipitated with ammonium sulfate and pellet resuspended in TBS. Positive controls for trypsin activity were boiled for 5 minutes before adding trypsin. Trypsin was added in a final concentration of 0.05% and all samples were heated for 10 minutes at 30 °C. Reaction was stopped by adding hot sample buffer. Separation and blotting was performed as described above. The P1 fragment of C7 was detected using the C7 NC2-10 antibody.

RNA isolation and quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction. RNA was isolated from cells with NucleoSpin RNA isolation kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions and transcribed to cDNA with First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction analyses were performed with a CFX96 Real-Time system (BioRad, Munich, Germany). Primers used were as follows: Gapdh forward GGCCTCCAAGGAGTAAGACC; Gapdh reverse AGGGTCTACATGGCAACTG; primer set 1 hCOL7A1 forward CTTCCTCCCGTCTTCTCCA; primer set 1 hCOL7A1 reverse CTCTGGTCCCCCTGGATTAC; primer set 2 hCOL7A1 forward ACGACCTTCTCTCCCAGAGG; primer set 2 hCOL7A1 reverse CTCTGGTCCCCCTGGATTAC.

Immunfluorescent staining. NHFs and MSCs were seeded on Collagen I coated glass slides and grew for 48 hours in culture medium + 50 µg/ml ascorbic acid. Glass slides were shortly washed in 3 mmol/l MgCl2 and then fixed for 15 minutes in 4 °C cold paraformaldehyde (PFA) (4% in PBS). Free aldehyde groups were blocked with 50 mmol/l NH4Cl and samples were washed before incubating them for 3 minutes in 0.1% Triton-X-100/TBS. Slides were blocked in 3% BSA/PBS before proceeding with antibody incubation. Skin sections were fixed in acetone, blocked, and stained with primary and secondary antibodies, counterstained with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), and mounted in Fluorescence Mounting Medium (Dako). Images were acquired with an Axiocam MRm camera attached to a Zeiss Axio Imager A1 fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany), processed using Axiovision 4.9 and ZEN2012 software (Carl Zeiss), and quantified with Image J.

Cell injections. Cells were washed three times with PBS after trypsinization and kept in 100 µl PBS in the cell concentration required for the experiment. PBS was chosen as transport medium to avoid introduction of foreign proteins or impurities and could be used as the time span between preparation and injection was always less than 1 hour. Cells were rigorously tested for viability by replating MSCs undergoing identical treatment and transport as MSCs designated for injections. The MSCs showed a good (>95%) viability after this procedure indicating that PBS was a suitable medium for temporary transport. C7-hypomorphic mice28 were injected intradermally with MSCs or PBS alone with a 27 G needle (B.Braun, Melsungen, Germany) in total covering an area of 1 cm2. Injections were divided into four injections á 25 µl to avoid traumata of the instable skin.

TUNEL assay. Apoptotic cells were identified in tissue sections using the In situ Cell Death Reaction Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Assessment of wound healing after MSCs injections. Assessment of wound healing was described previously.28 In brief, 4- to 6-week-old C7-hypomorphic mice and wild-type littermates were used for wound healing studies. Before wounding, mice were randomly divided into two groups; one to receive PBS and one to receive MSC treatment. The mice were then shaved and two full thickness skin wounds were incised at the mid-back under isofluorane anesthesia with a 6-mm punch biopsy device (Pfm medical, Cologne, Germany). After wounding, mice were kept in single cages and monitored daily for rewounding. Directly after wound induction, wounds were photographed with a Canon power shot S3IS camera (Canon, Krefeld, Germany) and this wound size was set as original wound size in later quantification. Eight hours after wounding, 2 × 106 MSCs dissolved in 100 µl PBS or PBS alone were injected at the wound edges and this procedure was repeated 48 hours after the first injection. Injections were divided into 4 á 25 µl injections, which were placed in a distance of 2 mm of each wound edge, thereby spanning an area of 1 cm2. Photos were captured on all days after wounding in a standardized way using a sticky ruler as a reference for quantification. At the end of the experiment, photographs were blinded and given to a researcher who performed the quantification using Image J.

The two wounds on each mouse were divided for analyzing purposes. One wound was used for immunofluorescence analysis by embedding it in Tissue-Tek optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound (Sakura, Staufen, Germany) followed by snap freezing, the second one fixed in 10% formalin or 4% paraformaldehyde/2% glutaraldehyde for histology or electron microscopy (EM) analysis. Gross wound closure was quantified by Image J (NIH), and wound healing was expressed as the percentage of the nonhealed original wound area, calculated as (wound area day x/wound area day 0)) × 100. Re-epithelialization was determined by H&E staining of serial sections from the middle of the wounds; images were acquired using an Axiocam MRm camera attached to a Zeiss Axio Imager A1 microscope (Carl Zeiss). Percentage of re-epithelialization was quantified with Image J.

Tape strip assay. Skin stability of 4-week-old wounds was assessed by inducing mechanical stress to skin of C7-hypomorphic mice. Briefly, a Scotch tape was placed over a shaved and cleaned wound area and then removed in one snapping motion. This was repeated twice with new tape strips so that in total three stripes were attached and removed. Mice were scarified and wounds carefully excised, fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin. 6 μm sections were cut through the entire wound and every 10th section was H&E stained and analyzed for epithelial separation. Multiple mice and wounds were used (n = 4).

Electron microscopy. For electron microscopy, specimens of MSC- and PBS-injected skin were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/2% glutaraldehyde at 4 °C. They were then washed twice in 0.1 mol/l cacodylate buffer and incubated in 1% osmium tetroxide solution for 1 hour. Samples were dehydrated in ethanol (25, 50, 75, 90, 100%) and propylene oxide and embedded in an epoxy resin. Sections (70 nm) were mounted on microscopy grids, stained with 5% uranyl acetate Reynold's solution, and examined with a JEM 1400 (JEOL, Eching, Germany) transmission electron microscope equipped with a TVIPS 2K digital camera. Anchoring fibril density and diameter were determined as previously described.33,34

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Figure S1. Western blots of representative MSC-donor characterization. Figure S2. Injections of MSCs cause a mild transient inflammation. Figure S3. Polyclonal rabbit antibody against human LH7.2 domain displays specificity for human C7. Figure S4. Injected MSCs gradually undergo apoptosis after administration in C7-hypomorphic mice. Figure S5. No indications of C7-specific immune reactions in MSC-injected C7-hypomorphic skin. Figure S6. MSCs do not influence gross wound closure in wild-type animals. Figure S7. MSCs promote de novo formation of immature anchoring fibrils. Materials and Methods

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Debra Austria (Nr. Bruckner-Tuderman/Handgretinger 1), the German Research Foundation DFG (Nr. Br1475/12-1), A.N. was supported by a grant from the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research BMBF, under the frame of E-Rare-2, the ERA-Net for Research Programmes on Rare Diseases and M.M. was supported by a grant from the Fortüne programme Tübingen (2021-0-0). The authors thank Renate Ayubi and Ulrike Vogt for expert technical assistance. Special thanks to Claudia Treuner and Renate Koch for their excellent technical assistance with GMP-conform production of MSCs.

Supplementary Material

References

- Aymé, S, Rodwell, C, eds. (2013). 2013 Report on the State of the Art of Rare Disease Activities in Europe. Publisher: European Union, Brussels. [Google Scholar]

- Griggs, RC, Batshaw, M, Dunkle, M, Gopal-Srivastava, R, Kaye, E, Krischer, J et al.; Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network. (2009). Clinical research for rare disease: opportunities, challenges, and solutions. Mol Genet Metab 96: 20–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine, JD, Bruckner-Tuderman, L, Eady, RA, Bauer, EA, Bauer, JW, Has, C et al. (2014). Inherited epidermolysis bullosa: updated recommendations on diagnosis and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol 70: 1103–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Has, C and Bruckner-Tuderman, L (2014). The genetics of skin fragility. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 15: 245–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Agtmael, T and Bruckner-Tuderman, L (2010). Basement membranes and human disease. Cell Tissue Res 339: 167–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aumailley, M, Has, C, Tunggal, L and Bruckner-Tuderman, L (2006). Molecular basis of inherited skin-blistering disorders, and therapeutic implications. Expert Rev Mol Med 8: 1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung, HJ and Uitto, J (2010). Type VII collagen: the anchoring fibril protein at fault in dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Dermatol Clin 28: 93–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertheim-Tysarowska, K, Sobczyńska-Tomaszewska, A, Kowalewski, C, Skroński, M, Swięćkowski, G, Kutkowska-Kaźmierczak, A et al. (2012). The COL7A1 mutation database. Hum Mutat 33: 327–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Akker, PC, Jonkman, MF, Rengaw, T, Bruckner-Tuderman, L, Has, C, Bauer, JW et al. (2011). The international dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa patient registry: an online database of dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa patients and their COL7A1 mutations. Hum Mutat 32: 1100–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uitto, J and Richard, G (2004). Progress in epidermolysis bullosa: genetic classification and clinical implications. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 131C: 61–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine, JD (2010). Inherited epidermolysis bullosa. Orphanet J Rare Dis 5: 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruckner-Tuderman, L, McGrath, JA, Robinson, EC and Uitto, J (2013). Progress in Epidermolysis bullosa research: summary of DEBRA International Research Conference 2012. J Invest Dermatol 133: 2121–2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruckner-Tuderman, L (2014). Small-molecule therapies for genetic skin fragility. Mol Ther 22: 1724–1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogan, J, Weinstein, J, Wang, X, Hou, Y, Martin, S, South, AP et al. (2014). Aminoglycosides restore full-length type VII collagen by overcoming premature termination codons: therapeutic implications for dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Mol Ther 22: 1741–1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venugopal, SS, Yan, W, Frew, JW, Cohn, HI, Rhodes, LM, Tran, K et al. (2013). A phase II randomized vehicle-controlled trial of intradermal allogeneic fibroblasts for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. J Am Acad Dermatol 69: 898–908.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrof, G, Martinez-Queipo, M, Mellerio, JE, Kemp, P and McGrath, JA (2013). Fibroblast cell therapy enhances initial healing in recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa wounds: results of a randomized, vehicle-controlled trial. Br J Dermatol 169: 1025–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, JE, Ishida-Yamamoto, A, McGrath, JA, Hordinsky, M, Keene, DR, Woodley, DT et al. (2010). Bone marrow transplantation for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. N Engl J Med 363: 629–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hünefeld, C, Mezger, M, Kern, JS, Nyström, A, Bruckner-Tuderman, L, Müller, I et al. (2013). One goal, different strategies–molecular and cellular approaches for the treatment of inherited skin fragility disorders. Exp Dermatol 22: 162–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conget, P, Rodriguez, F, Kramer, S, Allers, C, Simon, V, Palisson, F et al. (2010). Replenishment of type VII collagen and re-epithelialization of chronically ulcerated skin after intradermal administration of allogeneic mesenchymal stromal cells in two patients with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Cytotherapy 12: 429–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo, ME and Fibbe, WE (2013). Mesenchymal stromal cells: sensors and switchers of inflammation. Cell Stem Cell 13: 392–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Németh, K, Leelahavanichkul, A, Yuen, PS, Mayer, B, Parmelee, A, Doi, K et al. (2009). Bone marrow stromal cells attenuate sepsis via prostaglandin E(2)-dependent reprogramming of host macrophages to increase their interleukin-10 production. Nat Med 15: 42–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y, Chen, L, Scott, PG and Tredget, EE (2007). Mesenchymal stem cells enhance wound healing through differentiation and angiogenesis. Stem Cells 25: 2648–2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki, M, Abe, R, Fujita, Y, Ando, S, Inokuma, D and Shimizu, H (2008). Mesenchymal stem cells are recruited into wounded skin and contribute to wound repair by transdifferentiation into multiple skin cell type. J Immunol 180: 2581–2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, RH, Pulin, AA, Seo, MJ, Kota, DJ, Ylostalo, J, Larson, BL et al. (2009). Intravenous hMSCs improve myocardial infarction in mice because cells embolized in lung are activated to secrete the anti-inflammatory protein TSG-6. Cell Stem Cell 5: 54–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch, A, Loeckermann, S, Kern, JS, Braun, A, Bösl, MR, Bley, TA et al. (2008). A hypomorphic mouse model of dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa reveals mechanisms of disease and response to fibroblast therapy. J Clin Invest 118: 1669–1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern, JS, Loeckermann, S, Fritsch, A, Hausser, I, Roth, W, Magin, TM et al. (2009). Mechanisms of fibroblast cell therapy for dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: high stability of collagen VII favors long-term skin integrity. Mol Ther 17: 1605–1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haniffa, MA, Collin, MP, Buckley, CD and Dazzi, F (2009). Mesenchymal stem cells: the fibroblasts' new clothes? Haematologica 94: 258–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyström, A, Velati, D, Mittapalli, VR, Fritsch, A, Kern, JS and Bruckner-Tuderman, L (2013). Collagen VII plays a dual role in wound healing. J Clin Invest 123: 3498–3509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Y, Jiang, D, Sindrilaru, A, Stegemann, A, Schatz, S, Treiber, N et al. (2014). TSG-6 released from intradermally injected mesenchymal stem cells accelerates wound healing and reduces tissue fibrosis in murine full-thickness skin wounds. J Invest Dermatol 134: 526–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uemura, R, Xu, M, Ahmad, N and Ashraf, M (2006). Bone marrow stem cells prevent left ventricular remodeling of ischemic heart through paracrine signaling. Circ Res 98: 1414–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxson, S, Lopez, EA, Yoo, D, Danilkovitch-Miagkova, A and Leroux, MA (2012). Concise review: role of mesenchymal stem cells in wound repair. Stem Cells Transl Med 1: 142–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis, WJ, Sui, A and Bartholomew, A (2013). Stem Cells and Healing: Impact on Inflammation. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2: 369–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regauer, S, Seiler, GR, Barrandon, Y, Easley, KW and Compton, CC (1990). Epithelial origin of cutaneous anchoring fibrils. J Cell Biol 111(5 Pt 1): 2109–2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tidman, MJ and Eady, RA (1985). Evaluation of anchoring fibrils and other components of the dermal-epidermal junction in dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa by a quantitative ultrastructural technique. J Invest Dermatol 84: 374–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong, T, Gammon, L, Liu, L, Mellerio, JE, Dopping-Hepenstal, PJ, Pacy, J et al. (2008). Potential of fibroblast cell therapy for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. J Invest Dermatol 128: 2179–2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Blanc, K, Frassoni, F, Ball, L, Locatelli, F, Roelofs, H, Lewis, I et al.; Developmental Committee of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. (2008). Mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of steroid-resistant, severe, acute graft-versus-host disease: a phase II study. Lancet 371: 1579–1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodley, DT, Remington, J, Huang, Y, Hou, Y, Li, W, Keene, DR et al. (2007). Intravenously injected human fibroblasts home to skin wounds, deliver type VII collagen, and promote wound healing. Mol Ther 15: 628–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacini, S (2014). Deterministic and stochastic approaches in the clinical application of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs). Front Cell Dev Biol 2: 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel, D, Bayerl, J, Nyström, A, Bruckner-Tuderman, L, Meixner, A and Penninger, JM (2014). Genetically corrected iPSCs as cell therapy for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Sci Transl Med 6: 264ra165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prockop, DJ, Prockop, SE and Bertoncello, I (2014). Are clinical trials with mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells too far ahead of the science? Lessons from experimental hematology. Stem Cells 32: 3055–3061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaipe, H, Carlson, LM, Erkers, T, Nava, S, Molldén, P, Gustafsson, B et al. (2015). Immunogenicity of Decidual Stromal Cells in an Epidermolysis Bullosa Patient and in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Patients. Stem Cells Dev (epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wong, VW, Rustad, KC, Akaishi, S, Sorkin, M, Glotzbach, JP, Januszyk, M et al. (2012). Focal adhesion kinase links mechanical force to skin fibrosis via inflammatory signaling. Nat Med 18: 148–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern, JS, Grüninger, G, Imsak, R, Müller, ML, Schumann, H, Kiritsi, D et al. (2009). Forty-two novel COL7A1 mutations and the role of a frequent single nucleotide polymorphism in the MMP1 promoter in modulation of disease severity in a large European dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa cohort. Br J Dermatol 161: 1089–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, AS and Roffwarg, D (2013). Cutaneous verrucous xanthoma in a bone marrow transplant recipient with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Pediatr Dermatol 30: 480–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolar, J, Ishida-Yamamoto, A, Riddle, M, McElmurry, RT, Osborn, M, Xia, L et al. (2009). Amelioration of epidermolysis bullosa by transfer of wild-type bone marrow cells. Blood 113: 1167–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdoni, C, McGrath, JA and Tolar, J (2014). Preconditioning of mesenchymal stem cells for improved transplantation efficacy in recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Stem Cell Res Ther 5: 121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruckner-Tuderman, L, Nilssen, O, Zimmermann, DR, Dours-Zimmermann, MT, Kalinke, DU, Gedde-Dahl, T Jr et al. (1995). Immunohistochemical and mutation analyses demonstrate that procollagen VII is processed to collagen VII through removal of the NC-2 domain. J Cell Biol 131: 551–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller, I, Kordowich, S, Holzwarth, C, Isensee, G, Lang, P, Neunhoeffer, F et al. (2008). Application of multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells in pediatric patients following allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood Cells Mol Dis 40: 25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller, I, Kordowich, S, Holzwarth, C, Spano, C, Isensee, G, Staiber, A et al. (2006). Animal serum-free culture conditions for isolation and expansion of multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells from human BM. Cytotherapy 8: 437–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosset, FL, Takeuchi, Y, Battini, JL, Weiss, RA and Collins, MK (1995). High-titer packaging cells producing recombinant retroviruses resistant to human serum. J Virol 69: 7430–7436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx, JC, Allay, JA, Persons, DA, Nooner, SA, Hargrove, PW, Kelly, PF et al. (1999). High-efficiency transduction and long-term gene expression with a murine stem cell retroviral vector encoding the green fluorescent protein in human marrow stromal cells. Hum Gene Ther 10: 1163–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gieseke, F, Böhringer, J, Bussolari, R, Dominici, M, Handgretinger, R and Müller, I (2010). Human multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells use galectin-1 to inhibit immune effector cells. Blood 116: 3770–3779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyström, A, Buttgereit, J, Bader, M, Shmidt, T, Ozcelik, C, Hausser, I et al. (2013). Rat model for dominant dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: glycine substitution reduces collagen VII stability and shows gene-dosage effect. PLoS One 8: e64243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, T, Takahashi, K, Furukawa, F and Imamura, S (1994). The epitope for anti-type VII collagen monoclonal antibody (LH7:2) locates at the central region of the N-terminal non-collagenous domain of type VII collagen. Br J Dermatol 131: 472–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.