Abstract

Background

Peritumoral cysts are frequently associated with central nervous system (CNS) hemangioblastomas and often underlie neurologic morbidity and mortality. To determine their natural history and clinical impact, we prospectively analyzed hemangioblastoma-associated peritumoral cysts in von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL) patients.

Methods

VHL patients with 2 or more years of follow-up that were enrolled in prospective study at the National Institutes of Health were included. Serial, prospectively acquired, laboratory, genetic, imaging, and clinical data were analyzed.

Results

One hundred thirty-two patients (out of 225 VHL study patients with at least 2 years of follow-up) had peritumoral cysts that were followed for more than 2 years (total of 292 CNS peritumoral cysts). Mean age at study entrance was 37.4±13.1 years (median, 37.9; range, 12.3 to 65.1 years). Mean follow-up was 7.0±1.7 years (median, 7.3; range, 2.1 to 9.0 years). Over the study period, 121 of the 292 peritumoral cysts (41.4%) became symptomatic. Total peritumoral cyst burden was associated with genetic mutation (partial deletion versus missense; P=0.02). Development of new cysts was associated with larger number cysts at study enrollment (P=0.002) and younger age (P<0.0001). Cyst growth rate was associated with anatomic location (cerebellum cysts grew faster than spine and brainstem cysts; P=0.0002 and P=0.0008), younger age (under 35 years of age; P=0.0006) and development of new neurologic symptoms (P<0.0001). Cyst size at symptom production depended on anatomic location (P<0.0001; largest to smallest were found, successively, in the cerebellum, spinal cord, and brainstem). The most common location for peritumoral cysts was the cerebellum (184 cysts; 63%; P<0.0001).

Conclusions

Peritumoral cysts frequently underlie symptom formation that requires surgical intervention in VHL patients. Development of new cysts was associated a total number cysts at study enrollment and younger age. Total peritumoral cyst burden was associated with germline partial deletion of the VHL gene.

Keywords: cyst, central nervous system, hemangioblastoma, natural history, treatment, von Hippel-Lindau disease

INTRODUCTION

The most common von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL)-associated neoplasms are hemangioblastomas of the central nervous system (CNS).1, 2 Multiple craniospinal hemangioblastomas can be found in nearly 90% of VHL patients.3–10 Although CNS hemangioblastomas are benign tumors; they can cause significant neurologic morbidity and mortality due to mass effect caused by the tumor itself or, in many cases, an associated peritumoral cyst which forms adjacent to the tumor.11–13 Hemangioblastoma-associated peritumoral cysts form as plasma-ultrafiltrate leaks through permeable tumor vessels into the surrounding CNS tissue.14 Prior studies have estimated that over 70% of hemangioblastoma-related neurologic symptoms with sporadic occurrence and in VHL are more likely to be the result of the associated peritumoral cyst than the tumor itself.12–14

In spite of the frequent occurrence and deleterious effects of CNS hemangioblastoma-associated peritumoral cysts in VHL, their biologic features are not fully defined. Consequently, understanding their clinical impact in VHL and optimal management are not understood. To develop deeper insights into their natural history, biology and clinical management, we prospectively analyzed hemangioblastoma-associated peritumoral cysts using clinical, genetic, imaging and laboratory data in a large series of patients with VHL.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

VHL patients in a prospective study to determine the natural history of CNS tumors, including hemangioblastomas, in VHL were included.15 Informed consent from all patients was obtained before enrollment in this National Institutes of Health approved protocol (NIH#00-N-0140). Diagnosis of VHL was confirmed in study patients using genetic testing and/or diagnostic clinical criteria.16, 17

Germline Genotype Analysis

Determination of germline mutations in the VHL gene was achieved by peripheral blood sample analysis, as described previously.15, 18

Study Evaluation

Clinical and imaging assessment

Patients were evaluated with neural axis imaging (MR-imaging) and clinical examinations at approximately 6-month intervals, as described previously.15

Cyst Characteristics

To best assess cyst biology and clinical features, patients and peritumoral cysts with less than 2-years follow-up were excluded.15 To avoid confounding data, imaging analysis was terminated in patients/cysts at the initiation of systemic chemotherapy, stereotactic radiosurgery, or craniospinal radiation.19, 20

MR-imaging was used to calculate hemangioblastoma (T1-weighted post contrast) and associated cyst (T2-weighted) volume by a modified ellipsoid formula at each visit.21 Cyst growth patterns were classified as saltatory (growth and quiescent periods), linear, or exponential. Cysts were classified as stable if they did not progress in size.15

Surgical Management

Symptomatic hemangioblastomas were resected, as described previously.22–25 The peritumoral cyst walls were left intact during the removal of the associated hemangioblastoma(s).

Statistical Analysis

Patient characteristics and hemangioblastoma features were summarized using descriptive statistics. Peritumoral cysts with 2 or more years follow-up, and a minimum of 4 clinical and radiographic time points were used to study cyst growth pattern. The cyst growth pattern was determined by mathematical characterization, as previously defined.15 Briefly, we applied a general linear model (SAS procedure GLM) to examine the association of subject cyst burden, the total number of cysts, with age (categorized as less than or equal to 35 years, or greater than 35 years), gender, years of follow-up and germline mutation type (partial deletion versus missense). This statistical model was also applied to assess the association of cyst burden (total number of cysts), cyst development (new cyst formation of study period), with age, gender, and total cyst number at study entrance and germline mutation type.

Because most subjects had more than 1 cyst, a general linear mixed model with the subject as random effect (procedure MIXED) was used to assess the association of growth rate with age, gender, symptoms and cyst location. To assess for the accuracy of prediction of symptoms using cyst size, receiver-operating-characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used. Survival analysis (Kaplan-Meier method) was performed using growing (cyst volume increased by at least 7.5 mm3) as an event of interest and the stable cysts were referred as censored. The time to event was defined as the time duration between the exam dates on which the cyst was detectable on imaging (12 mm3) to the exam date on which cyst enlargement was greater than 7.5 mm3. Because their distributions had a long right tail, quantitative outcome measures were logarithmically transformed. The difference of means based on transformed data was inverse transformed to fold. A P-value of equal to or less than 0.05 was used as significant. SAS version 9.2 was used for statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

A total of 250 VHL patients (accrual ceiling of protocol) were enrolled in the study. Two hundred twenty-five patients with 2 or more years follow-up were included in analysis. One hundred thirty-two (59%) of these patients (63 males, 69 females) had hemangioblastoma-associated peritumoral cysts at some point during their assessment. Mean age at study entrance was 37.4±13.1 years (median, 37.9; range, 12.3 to 65.1 years). Mean follow-up was 7.0±1.7 years (median, 7.3; range, 2.1 to 9.0 years).

Cyst Burden

Over the course of the study, 292 peritumoral cysts were identified in the 132 patients. The cysts were located in the cerebellum (184 cysts; 63.0% of the total number of cysts), brainstem (33 cysts; 11.3%), spinal cord (71 cysts; 24.3%) or supratentorial compartment (4 cysts; 1.4%).

Cyst Imaging Features

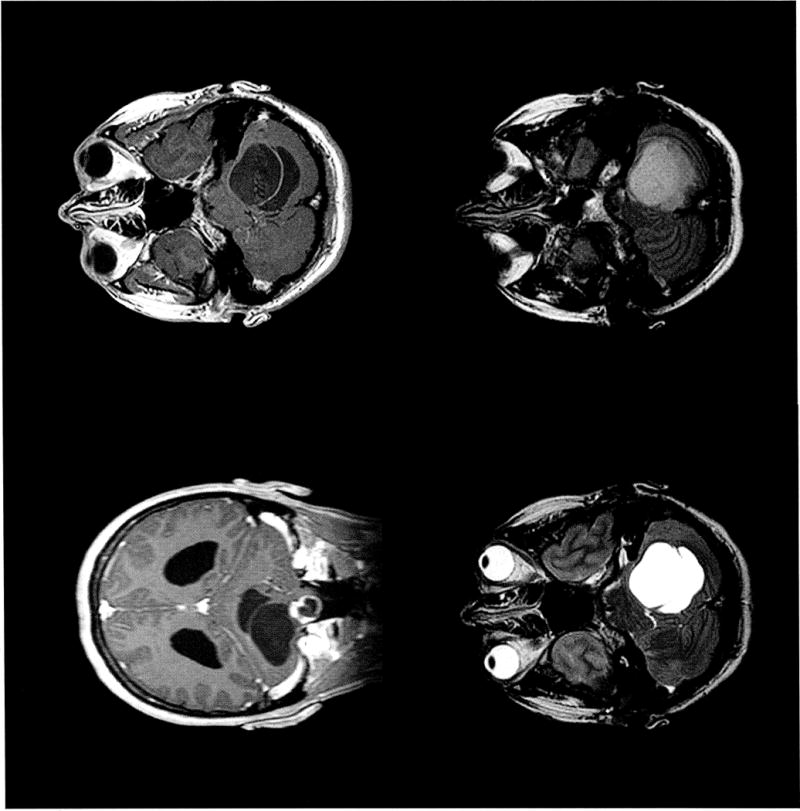

Hemangioblastoma-associated peritumoral cysts appeared hypointense on T1-weighted postcontrast images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images. The cysts were hypointense on precontrast FLAIR MR-imaging but hyperintense on postcontrast FLAIR MR-imaging (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging of cerebellar hemangioblastoma with associated peritumoral cyst. The cyst emanates superiorly from the enhancing lesion and causes dilation of fourth ventricle due to mass effect within the foramen magnum (top, left). This permits a unique ‘side-by-side’ view of the cyst and ventricle seen on gadolinium enhanced T1-weighted coronal and axial (top, left and right), T2-weighted axial (bottom, left), and FLAIR axial (bottom, right) images.

Cyst Progression

Cyst growth

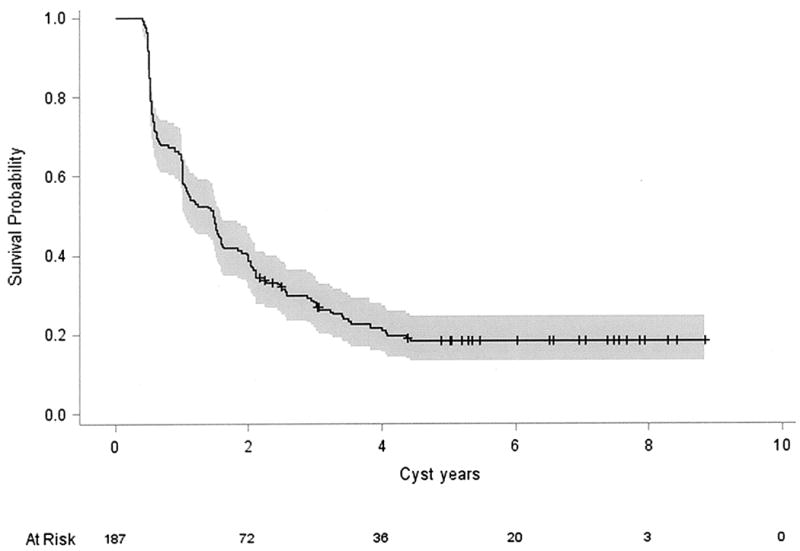

The incidence of progressive cyst growth depended on the interval of observation. Forty-seven cysts (25%) progressed in 0.6 years, 94 cysts (50.0%) progressed in 1.5 years and 141 (75.0%) progressed in 3 years (Figure 2). One hundred twenty-one cysts (41.4% of all cysts, 76% of all hemangioblastomas (hemangioblastomas with or without a cyst) associated with symptoms, caused symptoms and required surgical resection of the causative hemangioblastoma (correlation of presence of cyst with symptom formation P< 0.0001).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of peritumoral cyst progression in von Hippel-Lindau disease patients over an 8-year period. Twenty- five percent (47 cysts) progressed in 0.6 years, approximately half of cysts (94 cysts) progressed in 1.5 years and nearly three quarters progressed in 3 years.

Cysts growth rate were associated with cyst location, age and symptom. Mean cyst growth rate in the cerebellum was 1081.7±2732.1 mm3/year (cysts=117; median 131.3 mm3/year; range, 0 to 19,040.2 mm3/year; interquartile range [IQR]=695.0 mm3/year). Mean cyst growth rate in the brainstem was 171.7±346.2 mm3/year (cysts=23; median=12.1 mm3/year; range, 0 to 1282.6 mm3/year; IQR=167.8 mm3/year). Mean cyst growth rate in the spinal cord was 113.5±270.9 mm3/year (cysts=47; median=15.5 mm3/year; range, 0 to 1615.6 mm3/year; IQR=114.2 mm3/year).

Cyst growth rate was associated with location (cerebellar cysts grew faster than spinal cord (4.6-fold) and brainstem cysts (5.8-fold); P=0.0002 and P=0.0008). Cysts in patients with less than 35 years of age grew 3.5-fold faster than those in patients greater than 35 years (P=0.0006). Cysts associated with symptoms grew 15.7-fold faster than asymptomatic cysts (P<0.0001).

Pattern of growth

The pattern of peritumoral cyst growth was variable. Cysts (187 cysts had 2 year follow up that a growth pattern could be determined) grew in a saltatory (78 cysts; 41.7% of cysts), linear (18 cysts, 9.64%) or exponential (51 cysts; 27.2 %) pattern. Thirty-eight cysts (20.3%) remained stable over the observation period. Of the 60 symptomatic peritumoral cysts with over 2 years follow up, 20 cysts (33.9%) grew in a salutatory pattern, 27 cysts (45.8%) grew exponentially, 11 (18.6%) grew linearly, 1 cyst grew in an unknown pattern and 1 cyst did not grow.

Ratio of cyst to tumor size

Symptomatic cysts in the cerebellum had a significantly larger ratio of mean cyst size to corresponding tumor size (105.2±326.0; median, 10.6; range, 0.02 to 2047.4) compared to asymptomatic cerebellar cysts (10.9±27.2; median, 1.4; range, 0.01 to 18.5; P<0.0001). Symptomatic cysts in the brainstem had a significantly larger ratio of mean cyst size to corresponding tumor size of 7.0±10.6 (cysts=9; range, 0.06 to 31.6, median=1.6; IQR=11.9) compared to asymptomatic brainstem cysts (cysts=22; 4.8±11.9; range, 0.02 to 56.7; median=1.0; IQR=4.3; P<0.0001). Symptomatic cysts in the spinal cord had a significantly larger ratio of mean cyst size to corresponding tumor size of 13.8±18.5 (range, 0.03 to 59.5) compared to asymptomatic spinal cysts (mean, 3.6±6.3; range, 0.08 to 36.2; P<0.0001).

Symptomatic cysts in the cerebellum (76 cysts) had 3.4-fold (P<0.0001) larger mean ratio of cyst size to corresponding tumor size compared to asymptomatic cerebellar cysts (90 cysts). Symptomatic cysts in the spine (23 cysts) had 2.5-fold (P=0.0006) larger mean ratio of cyst size to corresponding tumor size compared to asymptomatic spinal cysts (48 cysts). As for brainstem (9 symptomatic cysts, 22 asymptomatic cysts), there was a 1.3-fold difference (P=0.5).

Factors Associated with Cyst Burden, Development and Size

Cyst burden

Increased cyst burden (total number of peritumoral cysts per patient) was associated with germline VHL mutation. Specifically, patients with a germline missense (0.7 cysts/patient) mutation had significantly fewer cysts than patients with partial deletions (1.1 cysts/patient; P=0.02) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Factors associated with cyst burden, development, growth and size

| Factor | P-value |

|---|---|

| Cyst Burden | |

| Age (>=35, <35) | 0.4 |

| Years of follow-up | 0.04 |

| Sex | 0.1 |

| Mutation (partial deletion vs. missense) | 0.02 |

| Cyst progression | |

| Age (>=35, <35) | <0.0001 |

| Number of cysts at study entrance | 0.002 |

| Sex | 0.05 |

| Mutation (partial deletion vs. missense) | 0.16 |

| Cyst size | |

| Location | <0.0001 |

| Sex | 0.5 |

| Mutation (partial deletion vs. missense) | 0.6 |

| Age (>=35, <35) | 0.5 |

| Years of follow-up (cyst) | 0.1 |

| Tumor symptomatic type | <0.0001 |

| Cyst growth rate | |

| Location | <0.0001 |

| Sex | 0.9 |

| Mutation (partial deletion vs. missense) | 0.9 |

| Age (>=35, <35) | 0.0006 |

| Tumor symptomatic type | <0.0001 |

New cyst development

Greater cyst burden at study entrance (P=0.002) and younger age (0.1 cysts/year in patients less than 35 years of age or 1.1-fold compared to 0.06 cysts/year if greater than 35 years of age; P<0.0001) were associated with an increased risk of new cyst development (Table 1).

Cyst size

Cyst size at symptom development was dependent on location (P<0.0001). Symptomatic cerebellum cysts were significantly (P<0.001) larger than symptom-causing spinal cysts (syringomyelia; 5.1-fold; P=0.001), and or brainstem cysts (syringobulbia; 8.2-fold; P=0.003) (mean cerebellum 3756 mm3 versus brainstem 456 mm3 and spine 730 mm3). There was no difference in size between symptom-producing spinal cysts and brainstem cysts (P=1.0). For asymptomatic cysts, there was no significant difference in size among the 3 locations (brainstem versus cerebellum, P=0.8; brainstem versus spine, P=1.0; cerebellum versus spine, P=0.1) (Table 1).

Factors that Predict Cyst-Associated Symptom Formation

ROC analysis demonstrated that cyst size thresholds in various anatomic regions can predict symptom formation (with area under ROC curve greater than 0.80). With a specificity threshold of 90% or more, cerebellar cysts attaining a diameter of 20.3 mm, brainstem cysts attaining diameter of 14.1 mm and spinal cord cysts attaining a diameter of 11.6 were predictably symptomatic.

Surgical Management of Hemangioblastomas Associated with Cysts

There were 121 hemangioblastomas (76.1% of all tumors with associated peritumoral cysts) with associated peritumoral cysts that were symptomatic and that required surgical resection. Symptomatic tumors were located in the cerebellum (86 tumors; 54.1% of surgical tumors), brainstem (9; 5.7%), spinal cord (23; 14.4%) or supratentorial compartment (1; 25%). All tumors were resected completely and this universally resulted in collapse or resolution of the associated peritumoral cyst. The cyst wall was not removed in any case.

DISCUSSION

Mechanisms of Peritumoral Cyst Formation

Previous studies demonstrate that tumor-associated peritumoral cysts develop through a predictable series of steps.14, 26 Specifically, high intratumoral pressure and increased vascular permeability associated with hemangioblastomas and the extremely high levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (originally known as vascular permeability factor)27 that they produce, underlie plasma ultrafiltrate entering the surrounding interstitial spaces. Ultrafiltrate from circulating plasma flows from the increased interstitial pressure of tumor parenchyma into the surrounding parenchyma interstitium producing local edema. Initially, the tissue has the capacity to resorb the excess fluid. However, as time progresses (i.e., with increasing tumor size, increasing pressure differential, increasing vascular permeability of the tumor vasculature, and/or chronic changes in the edematous tissue altering tissue capacity for resorbtion) and the ability of the tissue around the tumor to absorb the excess interstitial fluid is overcome, a cyst begins to form. The cyst will continue to grow until homeostasis between the rate of tumor plasma ultrafiltrate leakage and the rate of tissue resorption occurs.

Previous Studies

Previous studies have examined the presence of peritumoral cysts associated with hemangioblastomas in the CNS.12–14 These studies demonstrated that hemangioblastoma-associated peritumoral cysts are a frequent feature of hemangioblastomas when they occur sporadically or and in VHL patients. Moreover, these studies demonstrate that the presence of the peritumoral cyst and its associated mass effect can underlie the symptoms associated with CNS hemangioblastomas. Nevertheless, the previous studies were derived from retrospective analyses and they did not examine the biologic basis of peritumoral cysts.

To better understand the clinical impact and biology of hemangioblastoma-associated peritumoral cysts in an effort to improve management, we prospectively studied a large cohort of VHL patients over long-term follow-up.

Current Report

General features

Twelve percent of all VHL-associated CNS hemangioblastomas develop an associated peritumoral cyst. Nearly 60% of VHL patients in the current study developed a hemangioblastoma-associated peritumoral cyst. Peritumoral associated cysts were found in the cerebellum (63% of total cyst burden of the CNS in VHL), spinal cord (24%), brainstem (11%) and supratentorial compartment (1.4%). Clinically, approximately 60% of cysts that were followed for more than 2 years progressed and caused symptoms requiring surgical resection of the causative tumor. These findings underscore the critical impact that peritumoral cysts have on symptom formation and need for surgical treatment.

Imaging features

Consistent with previous data,14, 26 peritumoral cysts form due to leakage of plasma ultrafiltrate through permeable tumor vessels that starts as edema. This biologic feature is underscored by extravasation of gadolinium from the hemangioblastoma into the peritumoral cyst fluid on post-contrast FLAIR MR-imaging.28 Because post-contrast FLAIR MR-imaging is more sensitive to gadolinium in cerebrospinal fluid and cyst fluid than T1-wieghted MR-imaging,28 it is best for detecting this phenomenon. Further study may demonstrate that FLAIR MR-imaging could permit qualitative (or quantitative) assessment of peritumoral fluid extravasation after pharmacologic (e.g., steroid, vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors, bevacizumab or other similar agents) or other treatments (e.g., radiation).

Cyst distribution

The majority of peritumoral cysts occur in the cerebellum (63% of all cysts, 14% of all cerebellar hemangioblastomas). This is substantially greater than the spinal cord (24% of all cysts; 26% of spinal cord hemangioblastoma had an associated peritumoral cyst) and brainstem (11.4% of cysts, 20.0% of brainstem hemangioblastoma had an associated peritumoral cyst), despite that the overall distribution of CNS hemangioblastomas was equal between the cerebellum and spinal cord. The highest incidence of the occurrence of a cyst with a hemangioblastoma was in the brainstem and spinal cord. This may be due to differences in hydraulic conductivity of the spinal cord and brainstem compared to the cerebellum. These intrinsic anatomic differences in fluid transport may make the brainstem and spinal cord more prone to the generation of peritumoral cysts.

Cyst progression

After peritumoral cyst formation was identified on MR-imaging, cyst progression was a frequent finding. Half of all peritumoral cysts progressed within 1.5 years of observation and nearly three quarters (72.3%) progressed within 3 years. Further, 59% of cysts observed for more than 2 years had progressed enough to cause symptoms that required surgical resection of the associated hemangioblastoma. Cyst progression was rapid when compared to tumor progression (50% of tumors progressed in 5.6 to 8.9 years depending on tumor location whereas 50% of cysts progressed in 1.5 years). Consistent with mass effect underlying symptomatology, mean cerebellum cyst growth rate was 6 times faster than mean associated tumor growth rate. Similarly, the ratio of cyst growth rate to tumor growth rate of symptomatic cysts in the cerebellum was over 10 times faster than with asymptomatic cysts.

Factors affecting burden, development and size

Similar to hemangioblastoma burden, increased cyst burden was associated with genetic mutation type (Table 1). In particular, patients with partial deletions had more cysts than patients with missense mutations. Likewise, greater number of peritumoral cysts at study entrance and younger age were associated with increased risk of cyst development. Previous data demonstrate that VHL patients harboring more hemangioblastomas at the study entrance and younger age have been shown to have greater hemangioblastoma burden.15 Additionally, cysts causing symptoms in highly eloquent areas may occur at an earlier stage of progression. For example, cysts in the brainstem and spinal cord had symptoms from significantly smaller cysts than those in the cerebellum.

Features predictive of symptom formation

Predictive analysis indicates that the size of cyst based on anatomical location is a strong indicator of symptom formation. The values of sizes presented are general trends, and although larger cyst size was related to symptoms, in locations that are more eloquent, such as the brainstem, smaller hemangioblastomas can cause symptoms.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke at the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Glasker S. Central nervous system manifestations in VHL: genetics, pathology and clinical phenotypic features. Familial cancer. 2005;4(1):37–42. doi: 10.1007/s10689-004-5347-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richard S, Campello C, Taillandier L, Parker F, Resche F. Haemangioblastoma of the central nervous system in von Hippel-Lindau disease. French VHL Study Group. Journal of internal medicine. 1998 Jun;243(6):547–553. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1998.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lamiell JM, Salazar FG, Hsia YE. von Hippel-Lindau disease affecting 43 members of a single kindred. Medicine. 1989 Jan;68(1):1–29. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198901000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maher ER, Yates JR, Harries R, et al. Clinical features and natural history of von Hippel-Lindau disease. The Quarterly journal of medicine. 1990 Nov;77(283):1151–1163. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/77.2.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cockman ME, Masson N, Mole DR, et al. Hypoxia inducible factor-alpha binding and ubiquitylation by the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein. J Biol Chem. 2000 Aug 18;275(33):25733–25741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002740200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richard S, Chauveau D, Chretien Y, et al. Renal lesions and pheochromocytoma in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Advances in nephrology from the Necker Hospital. 1994;23:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neumann HP, Lips CJ, Hsia YE, Zbar B. Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. Brain pathology. 1995 Apr;5(2):181–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1995.tb00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maddock IR, Moran A, Maher ER, et al. A genetic register for von Hippel-Lindau disease. Journal of medical genetics. 1996 Feb;33(2):120–127. doi: 10.1136/jmg.33.2.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Filling-Katz MR, Choyke PL, Oldfield E, et al. Central nervous system involvement in Von Hippel-Lindau disease. Neurology. 1991 Jan;41(1):41–46. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neumann HP, Eggert HR, Scheremet R, et al. Central nervous system lesions in von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 1992 Oct;55(10):898–901. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.55.10.898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butman JA, Linehan WM, Lonser RR. Neurologic manifestations of von Hippel-Lindau disease. Jama. 2008 Sep 17;300(11):1334–1342. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.11.1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wanebo JE, Lonser RR, Glenn GM, Oldfield EH. The natural history of hemangioblastomas of the central nervous system in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease. Journal of neurosurgery. 2003 Jan;98(1):82–94. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.98.1.0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ammerman JM, Lonser RR, Dambrosia J, Butman JA, Oldfield EH. Long-term natural history of hemangioblastomas in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease: implications for treatment. Journal of neurosurgery. 2006 Aug;105(2):248–255. doi: 10.3171/jns.2006.105.2.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lonser RR, Vortmeyer AO, Butman JA, et al. Edema is a precursor to central nervous system peritumoral cyst formation. Annals of neurology. 2005 Sep;58(3):392–399. doi: 10.1002/ana.20584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lonser RR, Butman JA, Huntoon K, et al. Prospective natural history study of central nervous system hemangioblastomas in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Journal of neurosurgery. 2014 May;120(5):1055–1062. doi: 10.3171/2014.1.JNS131431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lonser RR, Glenn GM, Walther M, et al. von Hippel-Lindau disease. Lancet. 2003 Jun 14;361(9374):2059–2067. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13643-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melmon KL, Rosen SW. Lindau’s disease. Am J Med. 1964;36:595–617. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(64)90107-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stolle C, Glenn G, Zbar B, et al. Improved detection of germline mutations in the von Hippel-Lindau disease tumor suppressor gene. Human mutation. 1998;12(6):417–423. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1998)12:6<417::AID-HUMU8>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asthagiri AR, Mehta GU, Zach L, et al. Prospective evaluation of radiosurgery for hemangioblastomas in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Neuro-oncology. 2010 Jan;12(1):80–86. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simone CB, 2nd, Lonser RR, Ondos J, Oldfield EH, Camphausen K, Simone NL. Infratentorial craniospinal irradiation for von Hippel-Lindau: a retrospective study supporting a new treatment for patients with CNS hemangioblastomas. Neuro-oncology. 2011 Sep;13(9):1030–1036. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nor085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lundin P, Pedersen F. Volume of pituitary macroadenomas: assessment by MRI. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1992;16(4):519–528. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199207000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jagannathan J, Lonser RR, Smith R, DeVroom HL, Oldfield EH. Surgical management of cerebellar hemangioblastomas in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease. Journal of neurosurgery. 2008 Feb;108(2):210–222. doi: 10.3171/JNS/2008/108/2/0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wind JJ, Lonser RR. Management of von Hippel-Lindau disease-associated CNS lesions. Expert review of neurotherapeutics. 2011 Oct;11(10):1433–1441. doi: 10.1586/ern.11.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wind JJ, Bakhtian KD, Sweet JA, et al. Long-term outcome after resection of brainstem hemangioblastomas in von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Neurosurg. 2011 May;114(5):1312–1318. doi: 10.3171/2010.9.JNS10839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mehta GU, Asthagiri AR, Bakhtian KD, Auh S, Oldfield EH, Lonser RR. Functional outcome after resection of spinal cord hemangioblastomas associated with von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010 Mar;12(3):233–242. doi: 10.3171/2009.10.SPINE09592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lohle PN, van Mameren H, Zwinderman KH, Teepen HL, Go KG, Wilmink JT. On the pathogenesis of brain tumour cysts: a volumetric study of tumour, oedema and cyst. Neuroradiology. 2000 Sep;42(9):639–642. doi: 10.1007/s002340000363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berkman RA, Merrill MJ, Reinhold WC, et al. Expression of the vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor gene in central nervous system neoplasms. J Clin Invest. 1993;91(1):153–159. doi: 10.1172/JCI116165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lonser RR, Butman JA, Oldfield EH. Pathogenesis of tumor-associated syringomyelia demonstrated by peritumoral contrast material leakage. Case illustration. Journal of neurosurgery Spine. 2006 May;4(5):426. doi: 10.3171/spi.2006.4.5.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]