Abstract

Objective

Little is known about mental health services use by adults with prior suicidal behavior and current (12-month) psychiatric disorders. This study determined nationally representative prevalence estimates of current mental health services use by these adults, examining racial/ethnic, age, and gender differences.

Methods

Services use was examined across the life course using 1139 adults with history of suicidal behavior and current mood or anxiety disorders in the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys (CPES, 2001–2003).

Results

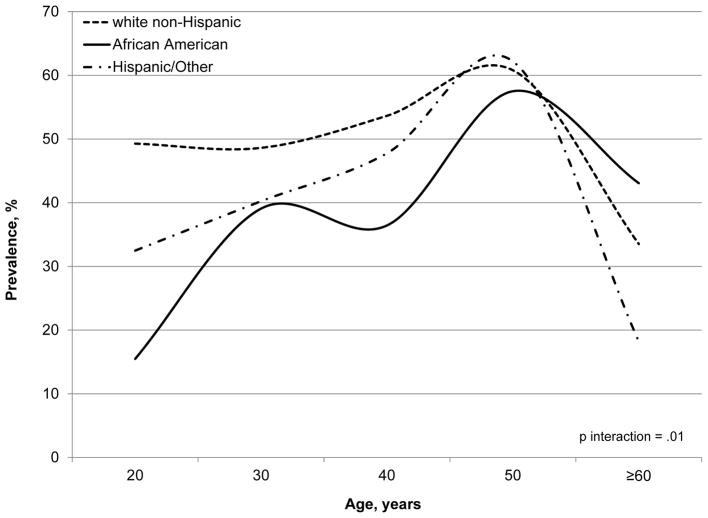

Overall services use was 47.3%. Across the life course, African Americans showed greater use that increasingly paralleled that by white non-Hispanics and Hispanics/Others, whose use decreased in the latter half of the life course (p interaction=.01).

Conclusions

Adults with prior suicidal behavior and current psychiatric disorders have low mental health services use. Findings of racial/ethnic disparities in use can help identify those in need of care.

INTRODUCTION

Suicide is a serious public health issue in the U.S. (1). It is the 10th leading cause of death after cardiovascular disease, cancer, and stroke (1,2). Studies suggest that prior suicidal behavior and psychiatric disorders are prominent factors that increase the likelihood of subsequent suicidal events (3). Research also indicates that mental health services use can help protect against suicide risk (3). Yet, the majority of studies on services use have not considered prior suicidal behavior (4–6). Thus, because suicide is a leading public health concern, research examining mental health services use by adults with history of suicidal behavior is crucial.

Previous studies on mental health services use have focused on adults with mood or anxiety disorders without considering those with prior suicidal behavior (4–6). Current understanding of services use may therefore not reflect the unique patterns of use by adults with prior suicidal behavior and current mood or anxiety disorders. Furthermore, although suicide and suicide risk vary by major health disparity factors such as race/ethnicity, age, and gender (7,8), few studies have considered these differences in the examination of services use and no study to our knowledge has investigated how these factors may work together to affect use. Thus, research investigating racial/ethnic, age, and gender disparities in mental health services use by adults with history of suicidal behavior and current mood or anxiety disorders is needed. Findings from such studies will inform present understanding of use and identify those in need of care.

Data from the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys (CPES, 2001–2003) uniquely address these limitations. In contrast to the surveys employed in previous studies, CPES data contain clinically-based measures of prior suicidal behavior and mood and anxiety disorders and are nationally representative of the racial/ethnic, age, and gender distributions of community-dwelling adults in the U.S.

Using CPES data, the objective of the present investigation was to determine nationally representative prevalence estimates of current mental health services use by adults with prior suicidal behavior and current mood or anxiety disorders in the U.S. and to examine racial/ethnic, age, and gender differences in use.

METHODS

The sample consisted of 1139 adults (≥18 years) in the CPES. All adults had prior non-fatal suicidal behavior (based on a lifetime assessment of suicidal ideation, plans, and attempts) and satisfied DSM-IV criteria for current mood (major depressive disorder, dysthymia, and bipolar disorders types I and II) or anxiety (panic disorder, agoraphobia without panic, specific phobia, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder) disorders, as determined by the World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI), in the past 12-months (i.e., only those with prior suicidal behavior and current mood or anxiety disorders were eligible to be in the study). All data were from the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. Participant consent was not obtained in the current investigation because the study involved the analysis of secondary data. The institutional review boards of the University of California, San Francisco and the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center approved this study.

The WMH-CIDI evaluated mental health services use by assessing the receipt of treatment for “emotions, nerves, mental health, or use of alcohol or drugs” (5). Current services use was defined as the receipt of specialty mental health (psychiatrist, psychologist, other mental health professional, social worker, or counselor in a mental health specialty setting; overnight hospital stay; or mental health hotline use) or general medical (primary care physician, other general practitioner or family doctor, nurse, occupational therapist, or other non-specialty mental health professional) treatment in the past 12-months. In this study, services use was examined across three major health disparity factors—race/ethnicity (white non-Hispanic, African American, or Hispanic/Other) (5), age (younger [18–34 years], middle [35–54 years], or older [≥55 years]), and gender.

Clustering and weighting techniques that reduce the systematic bias and imprecision in a complex sampling design were implemented to produce nationally representative prevalence estimates of services use that are generalizable to the U.S. population. Statistical differences were estimated by the Rao-Scott χ2 and standard errors were determined from a recalculation of variance using the Taylor series linear approximation method. To evaluate whether prevalence trends across the life course varied by race/ethnicity and gender, interaction terms with age modeled as continuous as well as main effects were examined in logistic regression analyses.

Reported results are based on weighted analyses unless otherwise noted. Statistical significance was defined as p<.05. All analyses were performed using SAS survey procedures (version 9.3, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

The mean±SD age of the sample was 38.6±13.7. The distribution was 41.7% younger age, 45.1% middle age, 13.2% older age, 44.3% white non-Hispanic, 27.0% African American, 28.7% Hispanic/Other (18.4% Hispanic, 6.5% Asian, and 3.8% Other), and 69.4% female, with whites being older, more educated, and more evenly located throughout the U.S. Furthermore, over 70% had prior suicidal behavior within the past 10 years and nearly half had suicidal behavior within the last 3 years. The distribution of prior suicidal behavior was 43.6% ideation only, 13.8% plan without an attempt, 26.9% plan with an attempt, and 15.6% attempt without a plan (i.e., impulsive attempt).

Overall, current mental health services use was 47.3%. African Americans showed the lowest use (32.2%) compared to whites (50.7%) and Hispanics/Others (41.0%; Rao-Scott χ2=17.1, df=2, p<.001) while adults in middle age showed the highest use (52.6%) compared to those in younger (41.9%) and older age (43.8%; Rao-Scott χ2=7.2, df=2, p=.03). Services use was similar between males (48.0%) and females (46.9%; Rao-Scott χ2=.06, df=1, p=.80).

Across the life course, African Americans showed increasingly greater services use, a pattern not seen among whites and Hispanics/Others, whose use decreased in the latter half of the life course (p interaction=.01; Figure). In younger age, African Americans had the lowest use (19.2%) compared to whites (47.5%) and Hispanics/Others (35.1%; Rao-Scott χ2=17.8, df=2, p<.001). A similar trend was seen in middle age despite overall increases in use. However, such disparity was absent in older age, as African Americans showed much greater services use (61.9%) that paralleled that by whites (44.0%) and Hispanics/Others (35.8%; Rao-Scott χ2=1.8, df=2, p=.40). This rise appeared to be motivated by increased general medical services use from younger (8.1%) to middle (17.6%) to older (54.2%) age, an occurrence absent in whites (21.0%, 34.6%, and 35.7%, respectively) and Hispanics/Others (23.6%, 33.3%, and 15.8%, respectively). Such findings were not seen for specialty mental health services use. Similar results were obtained from sensitivity analyses involving adults with recent history (≤3 years) of suicidal behavior and current mood or anxiety disorders, indicating that the reported findings are independent of the timing of suicidal behavior.

Figure.

Prevalence of current mental health services use across the life course in adults with prior suicidal behavior and current mood or anxiety disorders by race/ethnicitya

aData are reported as weighted percentages.

No gender differences in use were found across the life course and within age groups.

DISCUSSION

This study determined nationally representative prevalence estimates of current mental health services use by adults with prior suicidal behavior and current mood or anxiety disorders. Three key findings are important to highlight.

First, overall services use was low (<50%). This is consistent with previous research that suggests that adults with current suicidal ideation and mood (42%) or anxiety disorders (52%) show low use (9). Other studies have found similar results among those with current mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders (4–6,10). Although prior studies indicate that suicidal behavior motivates services use (10,11), our results underscore that even adults with history of suicidal behavior and current psychiatric disorders have low use.

Second, across the life course, African Americans showed greater services use that increasingly paralleled that by whites and Hispanics/Others. Although past studies suggest that racial/ethnic minorities with mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders or symptoms are likely to show lower services use than whites (5,12,13), few have considered racial/ethnic disparities in use across the life course. Moreover, no study to our knowledge has examined whether these differences pertain to adults with prior suicidal behavior and current mood or anxiety disorders.

Finally, the increased use across the life course by African Americans was driven by greater general medical services use. This is consistent with previous research that has found that African Americans show considerably higher general medical services use with age than whites for mental health treatment (14,15). Our findings thus support that African Americans with history of suicidal behavior and current psychiatric disorders also show increased general medical services use with age.

This study has strengths. It is the first to determine nationally representative prevalence estimates of current mental health services use by adults with prior suicidal behavior and current psychiatric disorders. It is also among the few to examine racial/ethnic, age, and gender differences in use and provide results that are generalizable to the U.S. population. However, this study also has limitations. Because CPES data underrepresent homeless, institutionalized, old-old (75–84 years), and oldest-old (≥85 years) adults, power for analyses of these segments of the life course may be limited. Power for analyses related to suicidal behavior severity (i.e., plans and attempts) was also limited and potential cohort effects, although difficult to assess in this study, should be considered. Finally, stigma may have discouraged those with psychiatric conditions from survey participation and validation of self-reported services use is unavailable.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings are informative yet concerning, as even adults with prior suicidal behavior and current psychiatric disorders underutilize mental health services. While our results reveal racial/ethnic differences in use, they emphasize the enduring tendency of African Americans to seek general medical services for mental health treatment, thereby further supporting the need for psychiatric and medical care integration. However, research is needed to explore how family, friends, community members, and technology can also provide support that can help reduce suicide and suicide risk.

Acknowledgments

This study used the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys (CPES, 2001–2003). The Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (Ann Arbor, Michigan) is responsible for the preparation, organization, and public access use of this data [http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/CPES]. The National Comorbidity Survey Replication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (U01-MH60220), with supplemental support from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (R01-DA12058-05), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (044708), and the John W. Alden Trust. The National Survey of American Life was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (U01-MH57716), with supplemental support from the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research at the National Institute of Health and from the University of Michigan. The National Latino and Asian American Study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (U01-MH062209, U01-MH62207), with supplemental support from the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research at the National Institute of Health, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Agency, and the Latino Research Program Project (P01-MH059876).

Dr. Byers is supported by a R01 Award (MD007019), administered by the Northern California Institute for Research and Education and with resources from the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center, from the National Institute of Health, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. Dr. Yaffe is partially supported by a K24 Midcareer Investigator Award (AG031155) from the National Institute on Aging.

Footnotes

A portion of this manuscript was presented at the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry’s Annual Meeting (March 29, 2015, New Orleans, Louisiana).

The authors report no competing interests.

References

- 1.Suicidal thoughts and behaviors among adults aged≥18 years—United States, 2008–2009. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leading Causes of Death. Number of deaths for leading causes of death. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); [Accessed December 15, 2014]. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Injury Prevention & Control. Division of Violence Prevention: Suicide: Risk and Protective Factors. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); [Accessed December 15, 2014]. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/suicide/riskprotectivefactors.html. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler RC, Demler O, Frank RG, et al. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;352:2515–2523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa043266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, et al. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:629–640. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blanco C, Okuda M, Wright C, et al. Mental health of college students and their non-college-attending peers: results from the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65:1429–1437. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.12.1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al. Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2008;30:133–154. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxn002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conwell Y, Thompson C. Suicidal behavior in elders. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2008;31:333–356. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brook R, Klap R, Liao D, et al. Mental health care for adults with suicide ideation. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2006;28:271–277. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mackenzie CS, Pagura J, Sareen J. Correlates of perceived need for and use of mental health services by older adults in the collaborative psychiatric epidemiology surveys. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2010;18:1103–1115. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181dd1c06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pagura J, Fotti S, Katz LY, et al. Help seeking and perceived need for mental health care among individuals in Canada with suicidal behaviors. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60:943–949. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.7.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ojeda VD, McGuire TG. Gender and racial/ethnic differences in use of outpatient mental health and substance use services by depressed adults. Psychiatric Quarterly. 2006;77:211–222. doi: 10.1007/s11126-006-9008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jimenez DE, Cook B, Bartels SJ, et al. Disparities in mental health service use of racial and ethnic minority elderly adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2013;61:18–25. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Powe NR, et al. Mental health service utilization by African Americans and Whites: the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area Follow-Up. Medical Care. 1999;37:1034–1045. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199910000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Snowden LR, Pingitore D. Frequency and scope of mental health service delivery to African Americans in primary care. Mental Health Services Research. 2002;4:123–130. doi: 10.1023/a:1019709728333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]