Highlights

-

•

Case of a combined (transsacral and laparoscopic) resection of a presacral tumour.

-

•

First described case of a transsacral rectocele two years after this procedure.

-

•

Possibility of laparoscopic defect repair of transsacral defects.

Abbreviations: BMI, body-mass-index; S3/4, sacral segment; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging

Keywords: Transsacral rectocele, Laparoscopic mesh graft implantation, Abdominotranssacral tumour resection, Presacral tumour

Abstract

Introduction

This report describes for the first time a case of a transsacral rectocele after combined abdominotranssacral tumour resection. Furthermore, we demonstrate a method for laparoscopic defect repair.

Presentation of case

A 44-year-old Caucasian female presented to our hospital with strange gurgling sounds and a painless subdermal swelling in her lower back after resection of a presacral neurinoma two years earlier. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a huge rectocele through a sacral defect extending into the subcutaneous tissue. We performed a laparoscopic defect repair with the implantation of a self-fixating mesh graft. Five days after surgery, the patient was discharged in a good general condition. Five months after the operation, a follow-up MRI showed a good postoperative result with the correct position of the rectum.

Discussion

The repair of transsacral prolapses with attachment of a mesh is complicated by the high rigidity of the pelvis and its surrounding structures. The key criteria in choosing the method of operative approach are the size and content of the prolapse. Huge sacral defects with bowel prolapses require a transabdominal approach to enable repositioning the bowel into the abdomen and excluding bowel injuries and inner hernias.

Conclusion

A laparoscopic approach provides a good intraoperative visibility for a safe retrorectal preparation and mesh graft repair of sacral defects.

1. Introduction

A transsacral approach offers a good operative access path for the resection of presacral tumours. Due to the size and level, a combined approach with laparoscopic mobilisation followed by an extended transsacral resection is sometimes necessary for tumour removal. A range of complications after this procedure have been reported, such as pelvic abscess, fistula formation, bowel obstruction and neural lesions with urinary incontinence or discomfort [1], [2]. Herein, we describe for the first time a case of a transsacral rectocele following combined neurinoma resection, as well as reconsidering the possibility of a surgical approach towards this issue.

2. Presentation of case

A 44-year-old Caucasian female presented with a history of dorsal pelvis bulge, which had been manifest for approximately one year. The patient underwent an uncomplicated resection of a huge (7 × 5 cm) presacral neurinoma two years earlier. The neurinoma appeared as an incidental finding in computed tomography while determining the origin of unspecific lumbar pain. The tumour was located on the anterior border of the vertebral body S4, extending into the lesser pelvis. Further diagnostic imaging revealed an infiltration of the neuroforamina in level S4 partly intraspinal, partly parasacral (Fig. 1). Based on these findings, a combined visceral and neurosurgical approach was performed to exclude an infiltration of the rectum. Following laparoscopic separation of the intrapelvinic parts (mesorectal dissection), the neurinoma was completely removed via a dorsal trans- and parasacral access path. For radical tumour resection, a microscope was used and adjacent osseous parts of vertebral body S4 were removed.

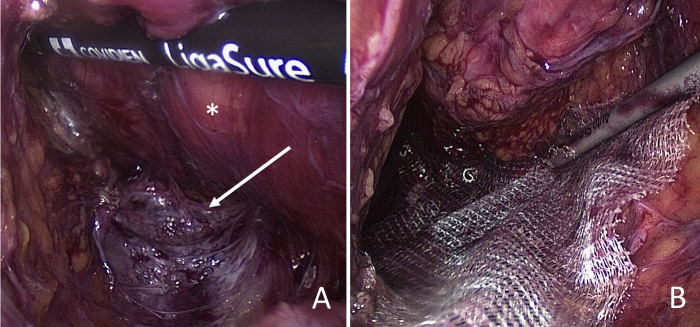

Fig. 1.

Sagittal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis showing a presacral tumour. The inhomogeneously enhancing tumour (maximal diameter of 7 cm) has contact to the sacralforamina S3/S4 on the right side and shows partial osseous destruction. There are no signs of rectal infiltration.

At the time of follow-up, the patient reported some “strange gurgling sounds” and a painless subdermal swelling originating from the area of the sacral surgical scar. Furthermore, she complained about recurring nausea and obstipation. Her further past medical history included a teratoma located in the lower abdomen, a neurogenic voiding dysfunction and laryngomalacia after long-term ventilation due to meningoencephalitis 17 years ago. The physical examination of an obese female (BMI 40 kg/m2) showed no focal neurological deficit. Beneath the apical part of the operation scar, a doughy, air-filled lesion was palpable. The prolapse was reducible and did not show any signs of incarceration. X-ray examination of the pelvis showed an inflated mass behind the sacrum (Fig. 2A). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a huge rectocele through a sacral defect extending into the subcutaneous tissue (Fig. 2B). There were no signs of tumour recurrence or residual tumour after application of a contrast agent in MRI.

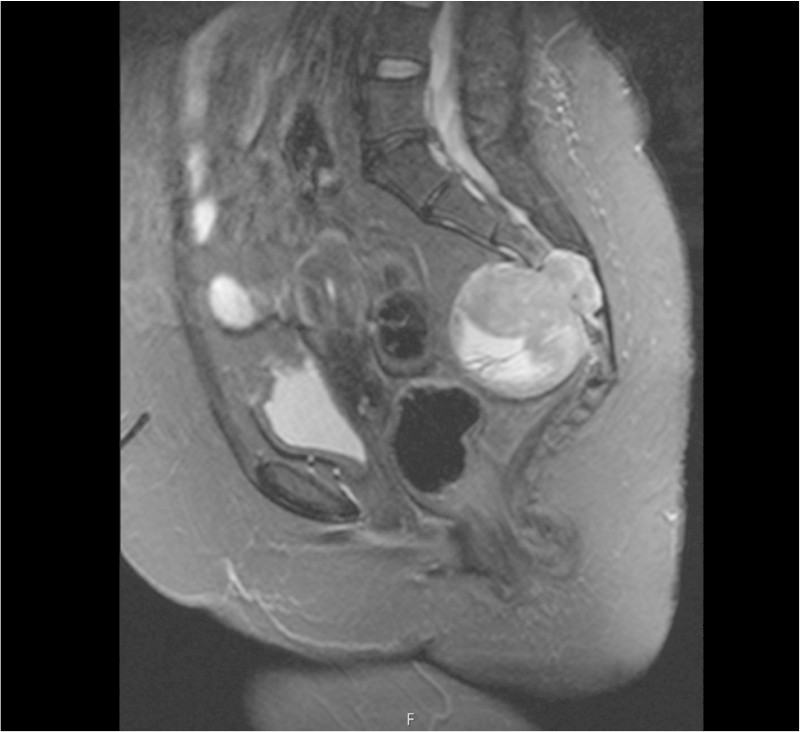

Fig. 2.

Two years after neurinoma resection. (A) Lateral X-ray picture of the pelvis showing an inflated mass behind the sacrum (circled). (B) Sagittal MRI scan showing a large bowel prolapse through sacrum defect (arrow).

The case of the patient was discussed on an interdisciplinary basis and we decided to perform a laparoscopic defect repair. After mesorectal dissection and repositioning of the prolabated bowel, intraoperative findings proved a large bone defect. Therefore, a mesh graft (ProGripTM, Laparoscopic Self-Fixating Mesh, Covidien Surgical Solutions, Mansfield, USA) was implanted and fixated with tacks (ProtackTM, Covidien Surgical Solutions, Mansfield, USA) (Fig. 3A,B). Finally, a rectopexy without resection was performed. Therefore, the rectum was fixed to the presacral fascia with simple sutures on each side. The postoperative course was uneventful. Five days after surgery, the patient was discharged in a good general condition.

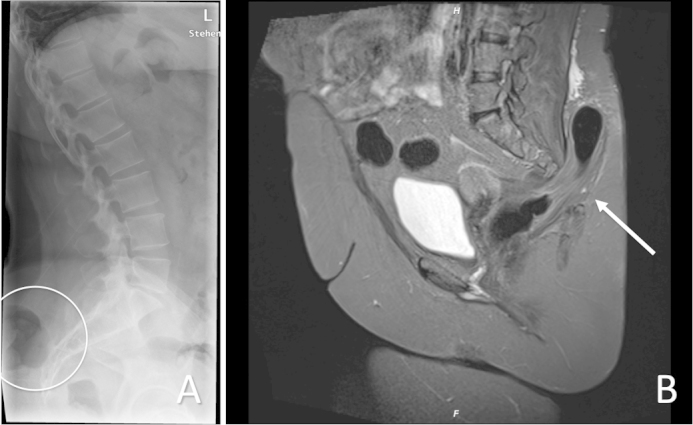

Fig. 3.

Intraoperative findings. (A) Note exposed prolapse orifice (arrow) and dorsal mesorectum (*). (B) Repair with mesh graft and spiral tacks.

Five months after the operation, a follow-up MRI showed the correct position of the rectum. Only scar changes were visible after elimination of the sacral rectocele (Fig. 4).

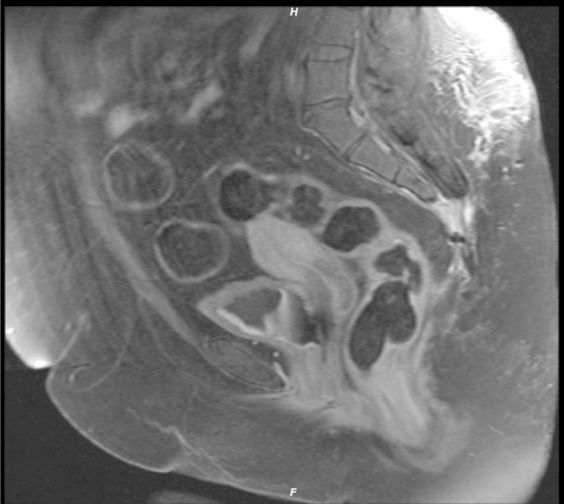

Fig. 4.

Five months after defect repair, MRI scan showing a good postoperative result. Scare changes are visible in the place of former rectocele, without signs of persisting prolapse.

3. Discussion

A surgical approach for resection of presacral tumours depends on the tumour level, size, suspected dignity and relationship to contiguous structures [1], [2], [3]. The patient in our report underwent a combined abdominotranssacral resection. A major benefit of the combined approach with previous laparoscopy and mesorectal dissection is the superior visibility and protection of the ureters and pelvic nerves and vessels. Furthermore, if rectal infiltration is revealed during the operation, an extended operation can be performed immediately. However, in consideration of the mostly uncertain tumour dignity, an initial closure of the ossary defect with prothetic material is not indicated, whereby mesorectal dissection might lead to a risk of bowel prolapses.

Due to the missing peritoneal covering and hernial sac, in our case the rectum prolapse does not represent a real hernia. In reviewing the literature, no data was found on acquired transsacral rectoceles. Sporadic cases of sacroperineal hernias after extended sacrectomy have been reported. For example, Atkin et al. described a case of a sacroperineal defect repair with mesh graft implantation via a transabdominal approach [4]. Nonetheless, contrast to our case, sacroperineal hernias are defects through the pelvic floor, rather than being transosseous. For comparison, acquired lumbar triangle hernias are known complications following iliac crest bone harvesting or trauma. Moreover, several open and laparoscopic extraperitoneal repairs have been described for lumbar defects, including the use of aponeurosis, prosthetic or bone straightening [5]. The rectum prolapse in our report could be repaired by laparoscopic mesh graft implantation. The key criteria in choosing the method of operative approach are the size and content of the prolapse. Huge sacral defects with bowel prolapses require a transabdominal approach to enable repositioning the bowel into the abdomen and excluding bowel injuries and inner hernias. Due to the risk of bowel incarceration and strangulation, efficient and rapid herniotomy should be strived [6]. A laparoscopic approach permits a good exposure with the additional benefit of abdominal exploration. Furthermore, the period of convalescence after laparoscopic surgery is shorter compared to conventional surgery.

In bone defects after iliac-crest harvesting larger than 4 cm2, the authors recommend the attachment of a mesh graft [7]. In our case, we used a self-fixating ProGripTM mesh with at least a 3 cm overlap beyond defect edges in all directions. Furthermore, we attached ProtackTM spirals for further fixation of the mesh. Owing to the risk of pelvic nerve injury, we used only one tack lateral. Cranial and caudal fixation includes a potential risk of damaging the presacral venous plexus, although it seems to be less complicated. The repair of transsacral prolapses by attaching a mesh is complicated by the high rigidity of the pelvis and its surrounding structures. Based upon our experience, laparoscopic mesh graft defect repair seems to be a low-risk procedure providing a good intraoperative visibility, which is essential in terms of creating a suitable net lair.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, laparoscopic evaluation and repair appears to be a safe and efficient approach in the management of transsacral prolapses.

Conflicts of interest

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding

No funding for research.

Ethical approval

Not applicable. No research study involved.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

Author contribution

Uwe Scheuermann did literature research and drafted the manuscript. Fabian Bartsch helped prepare the manuscript. Boris Jansen-Winkeln was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. Boris Jansen-Winkeln and Werner Kneist performed surgical operation for defect repair. Werner Kneist and Hauke Lang revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Guarantor

Uwe Scheuermann.

Contributor Information

Uwe Scheuermann, Email: uwe.scheuermann@medizin.uni-leipzig.de.

Fabian Bartsch, Email: fabian.Bartsch@unimedizin-mainz.de.

Boris Jansen-Winkeln, Email: boris.jansen-winkeln@medizin.uni-leipzig.de.

Hauke Lang, Email: hauke.lang@unimedizin-mainz.de.

Werner Kneist, Email: werner.kneist@unimedizin-mainz.de.

References

- 1.Böhm B., Milsom J.W., Fazio V.W., Lavery I.C., Church J.M., Oakley J.R. Our approach to the management of congenital presacral tumors in adults. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 1993;8(September (3)):134–138. doi: 10.1007/BF00341185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buchs N., Taylor S., Roche B. The posterior approach for low retrorectal tumors in adults. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2007;22(April (4)):381–385. doi: 10.1007/s00384-006-0183-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neale J.A. Retrorectal tumors. Clin. Colon Rectal Surg. 2011;24(September (3)):149–160. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1285999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atkin G., Mathur P., Harrison R. Mesh repair of sacral hernia following sacrectomy. J. R. Soc. Med. 2003;96(January (1)):28–30. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.96.1.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yurcisin B.M., Myers C.J., Stahlfeld K.R., Means J.R. Laparoscopic hernia repair following iliac crest harvest. Hernia. 2010;14(February (1)):93–96. doi: 10.1007/s10029-009-0499-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D'Hondt S., Soysal S., Kirchhoff P., Oertli D., Heizmann O. Small bowel obstruction caused by an incarcerated hernia after iliac crest bone harvest. ISRN Surg. 2011;2011 doi: 10.5402/2011/836568. 836568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Auleda J., Bianchi A., Tibau R., Rodriguez-Cano O. Hernia through iliac crest defects. Int. Orthop. 1995;19(6):367–369. doi: 10.1007/BF00178351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]